An Instrumental Variable Probit Modeling of COVID-19 Vaccination Compliance in Malawi

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The Study Area

2.2. The Data and Sampling Methods

2.3. Limitations of the Data

2.4. Data Merging and Variable Construction

- little interest or pleasure in doing things;

- feeling down, depressed, or hopeless;

- trouble falling or staying asleep, or sleeping too much;

- feeling tired or having little energy;

- poor appetite or overeating;

- feeling bad about yourself/or that you are a failure/have let yourself or family down;

- trouble concentrating on things, such as reading the newspaper/watching TV; and

- moving or speaking so slowly/or fast that other people could have noticed.

- household worried about not having enough food to eat;

- household unable to eat healthy and nutritious/preferred foods;

- household ate only a few kinds of foods;

- household had to skip a meal;

- household ate less than you thought you should;

- household ran out of food;

- household hungry but did not eat; and

- household went without eating for a whole day

2.5. Estimated Models

3. Results

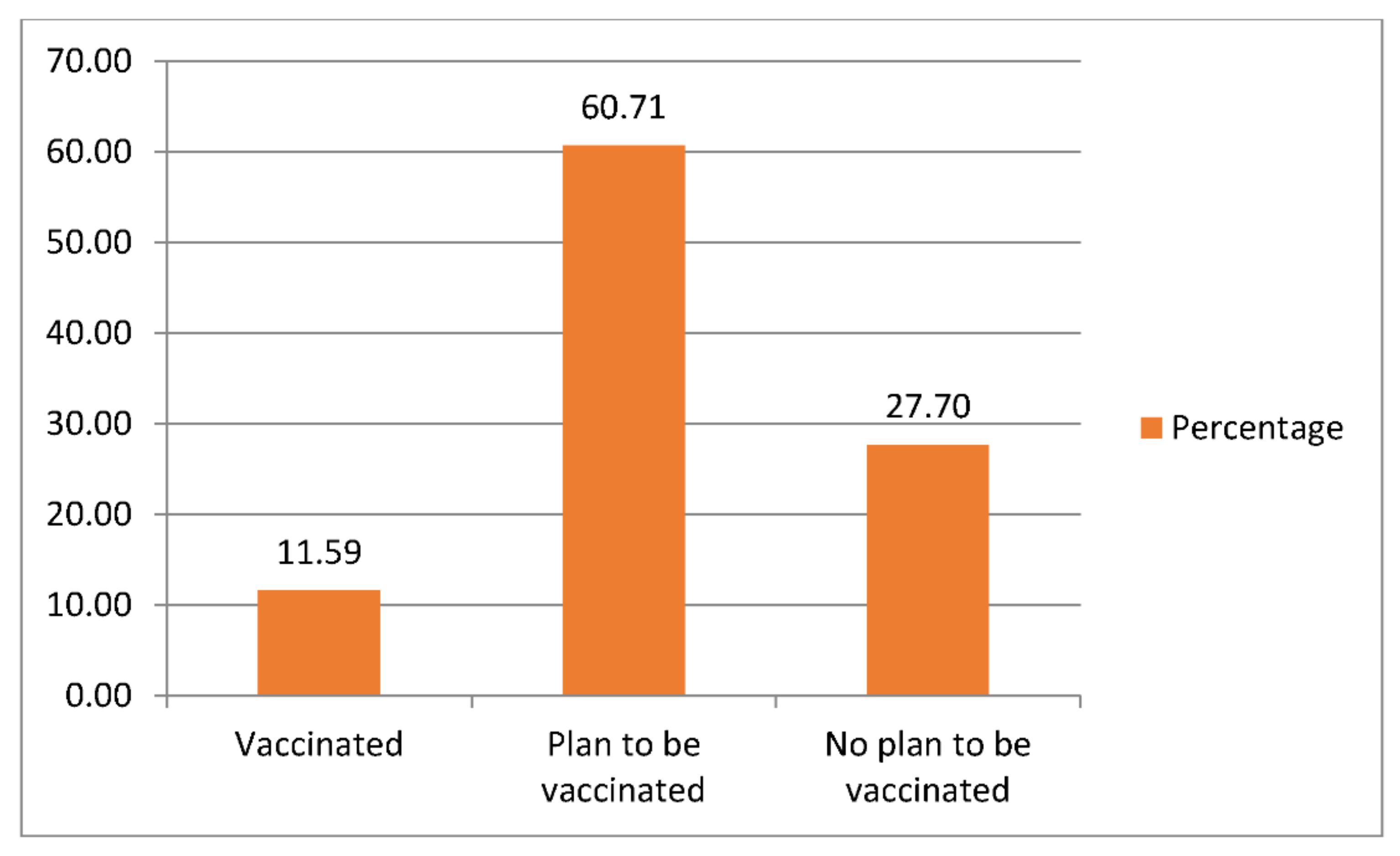

3.1. Respondents’ Demographic Characteristics and Decision to Be Vaccinated

3.2. Determinants of Being Vaccinated and Vaccination Compliance

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Makwero, M.T. Delivery of primary health care in Malawi. Afr. J. Prim. Health Care Fam. Med. 2018, 10, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messac, L. Rural Malawi: A Hard Place to Practice Medicine. 27 August 2013. Available online: https://pulitzercenter.org/stories/rural-malawi-hard-place-practice-medicine (accessed on 14 July 2021).

- Baulch, B.; Botha, R.; Pauw, K. Short-Term Impacts of COVID-19 on the Malawian Economy: Initial Results. Available online: http://ebrary.ifpri.org/utils/getfile/collection/p15738coll2/id/133788/filename/133999.pdf (accessed on 13 July 2021).

- World Bank. Malawi: Overview. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/malawi/overview (accessed on 13 July 2021).

- African Development Bank (ADB). Malawi Economic Outlook. Available online: https://www.afdb.org/en/countries/southern-africa/malawi/malawi-economic-outlook (accessed on 13 July 2021).

- Richard, M. Poverty and Inequality in Malawi: Trends, Prospects, and Policy Simulations. MPRA Paper No. 75979, Posted 04 Jan 2017 17:10 UTC. Available online: https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/75979/ (accessed on 15 July 2021).

- Callaway, E. Delta Coronavirus Variant: Scientists Brace for Impact, 22 June 2021. Available online: https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-021-01696-3 (accessed on 14 July 2021).

- Nyasulu, J.C.Y.; Munthali, R.J.; Nyondo-Mipando, A.L.; Pandya, H.; Nyirenda, L.; Nyasulu, P.S.; Manda, S. COVID-19 pandemic in Malawi: Did public sociopolitical events gatherings contribute to its first-wave local transmission? Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2021, 106, 269–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kao, K.; Lust, E.; Dulani, B.; Ferree, K.E.; Harris, A.S.; Metheney, E. The ABCs of Covid-19 prevention in Malawi: Authority, benefits, and costs of compliance. World Dev. 2021, 137, 105167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mzumara, G.W.; Chawani, M.; Sakala, M.; Mwandira, L.; Phiri, E.; Milanzi, E.; Phiri, M.D.; Kazanga, I.; O’Byrne, T.; Zulu, E.M.; et al. The health policy response to COVID-19 in Malawi. BMJ Glob. Health 2021, 6, e006035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amegah, A.K. Improving handwashing habits and household air quality in Africa after COVID-19. Lancet Glob. Health 2020, 8, e1110–e1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, I. Viewpoint—Handwashing and COVID-19: Simple, right there…? World Dev. 2020, 135, 105086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewnard, J.A.; Lo, N.C. Scientific and ethical basis for social-distancing interventions against COVID-19. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2020, 20, 631–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Greenhalgh, T.; Schmid, M.B.; Czypionka, T.; Bassler, D.; Gruer, L. Face masks for the public during the covid-19 crisis. BMJ 2020, 369, m1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Morawska, L.; Tang, J.W.; Bahnfleth, W.; Bluyssen, P.M.; Boerstra, A.; Buonanno, G.; Cao, J.; Dancer, S.; Floto, A.; Franchimon, F.; et al. How can airborne transmission of COVID-19 indoors be minimised. Environ. Int. 2020, 142, 105832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Regional Office for the Western Pacific. 2020. Routine Immunization Services during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Manila: WHO Regional Office for the Western Pacific. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/331925 (accessed on 14 July 2021).

- Kerr, J.; Freeman, A.; Marteau, T.; van der Linden, S. Effect of Information about COVID-19 Vaccine Effectiveness and Side Effects on Behavioural Intentions: Two Online Experiments. Vaccines 2021, 9, 379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graeber, D.; Schmidt-Petri, C.; Schröder, C. Attitudes on voluntary and mandatory vaccination against COVID-19: Evidence from Germany. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0248372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noh, J.Y.; Jeong, H.W.; Shin, E.-C. SARS-CoV-2 mutations, vaccines, and immunity: Implication of variants of concern. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2021, 6, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menni, C.; Klaser, K.; May, A.; Polidori, L.; Capdevila, J.; Louca, P.; Sudre, C.H.; Nguyen, L.H.; Drew, D.A.; Merino, J.; et al. Vaccine side-effects and SARS-CoV-2 infection after vaccination in users of the COVID Symptom Study app in the UK: A prospective observational study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2021, 21, 939–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolovski, J.; Koldijk, M.; Weverling, G.J.; Spertus, J.; Turakhia, M.; Saxon, L.; Gibson, M.; Whang, J.; Sarich, T.; Zambon, R.; et al. Factors indicating intention to vaccinate with a COVID-19 vaccine among older U.S. adults. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0251963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abedin, M.; Islam, M.A.; Rahman, F.N.; Reza, H.M.; Hossain, M.Z.; Arefin, A.; Hossain, A. Willingness to vaccinate against COVID-19 among Bangladeshi adults: Understanding the strategies to optimize vaccination coverage. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0250495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Luo, X.; Ma, Z.F. Willingness of the general population to accept and pay for COVID-19 vaccination during the early stages of COVID-19 pandemic: A nationally representative survey in mainland China. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2021, 17, 1622–1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, F.; Li, X.; Su, X.; Xiao, T.; Wang, Y.; Hu, P.; Li, H.; Guan, J.; Tian, H.; Wang, P.; et al. A study on willingness and influencing factors to receive COVID-19 vaccination among Qingdao residents. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2021, 17, 408–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Bank. Employment in Agriculture (% of Total Employment) (Modeled ILO Estimate)—Malawi, 2021. 2021. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SL.AGR.EMPL.ZS?locations=MW (accessed on 15 July 2021).

- SADC. SADC Selected Economic and Social Indicators 2019. 2020. Available online: https://www.sadc.int/files/2916/0102/7136/Selected_Indicators_2020_September_11v2.pdf (accessed on 15 July 2021).

- World Health Organization (WHO). Malawi Health Situation. Available online: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/136935/ccsbrief_mwi_en.pdf;jsessionid=64E915C2B9F1944327B3A65F2263F179?sequence=1#:~:text=Malawi%20is%20characterized%20by%20a,AIDS%20and%20other%20tropical%20diseases.&text=However%2C%20the%20prevalence%20rate%20remains,general%20population%20(all%20ages) (accessed on 15 July 2021).

- World Bank. Malawi—COVID-19 High Frequency Phone Survey of Households (HFPS) 2020. Ref: MWI_2020_HFPS_v08_M. Available online: www.microdata.worldbank.org (accessed on 15 July 2021).

- Shacham, M.; Greenblatt-Kimron, L.; Hamama-Raz, Y.; Martin, L.; Peleg, O.; Ben-Ezra, M.; Mijiritsky, E. Increased COVID-19 Vaccination Hesitancy and Health Awareness amid COVID-19 Vaccinations Programs in Israel. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skeels, C.L.; Tarlor, L.T. Prediction in linear index models with endogenous regressors. Stata J. 2015, 15, 627–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chinele, J. No VIP Treatment: Malawi Aims for An Equitable COVID-19 Vaccine Roll-Out, 5 April 2021. Available online: https://www.gavi.org/vaccineswork/no-vip-treatment-malawi-aims-equitable-covid-19-vaccine-roll-out (accessed on 19 July 2021).

- Sniehotta, F.F.; Presseau, J.; Araújo-Soares, V. Time to retire the theory of planned behaviour. Health Psychol. Rev. 2014, 8, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19): Herd Immunity, Lockdowns and COVID-19. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/q-a-detail/herd-immunity-lockdowns-and-covid-19?gclid=CjwKCAjwos-HBhB3EiwAe4xM91DLRYXcuDtuyLTu3DREusid2HSVbWNW50zCKnwqWyol5sg5m5XEdxoCA4sQAvD_BwE# (accessed on 19 July 2021).

- Green, M.S.; Abdullah, R.; Vered, S.; Nitzan, D. A study of ethnic, gender and educational differences in attitudes toward COVID-19 vaccines in Israel—Implications for vaccination implementation policies. Isr. J. Health Policy Res. 2021, 10, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlsson, L.C.; Soveri, A.; Lewandowsky, S.; Karlsson, L.; Karlsson, H.; Nolvi, S.; Karukivi, M.; Lindfelt, M.; Antfolk, J. Fearing the disease or the vaccine: The case of COVID-19. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2021, 172, 110590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galasso, V.; Pons, V.; Profeta, P.; Becher, M.; Brouard, S.; Foucault, M. Gender differences in COVID-19 attitudes and behavior: Panel evidence from eight countries. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 27285–27291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griffith, D.M.; Sharma, G.; Holliday, C.S.; Enyia, O.K.; Valliere, M.; Semlow, A.R.; Stewart, E.C.; Blumenthal, R.S. Men and COVID-19: A Biopsychosocial Approach to Understanding Sex Differences in Mortality and Recommendations for Practice and Policy Interventions. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2020, 17, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): Older Adults. 2020. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/need-extra-precautions/older-adults.html (accessed on 14 July 2021).

- Montecino-Rodriguez, E.; Berent-Maoz, B.; Dorshkind, K. Causes, consequences, and reversal of immune system aging. J. Clin. Investig. 2013, 123, 958–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaw, A.C.; Joshi, S.; Greenwood, H.; Panda, A.; Lord, J.M. Aging of the innate immune system. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2010, 22, 507–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Linton, P.J.; Dorshkind, K. Age-related changes in lymphocyte development and function. Nat. Immunol. 2004, 5, 133–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrivastava, S.R.; Shrivastava, P.S.; Ramasamy, J. Health-care of Elderly: Determinants, Needs and Services. Int. J. Prev. Med. 2013, 4, 1224–1225. [Google Scholar]

- Drobnik, J.; Susło, R.; Pobrotyn, P.; Fabich, E.; Magiera, V.; Diakowska, D.; Uchmanowicz, I. COVID-19 among Healthcare Workers in the University Clinical Hospital in Wroclaw, Poland. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tengatenga, J.; Duley, S.T.; Tengatenga, C. Zimitsani Moto: Understanding the Malawi COVID-19 Response. Laws 2021, 10, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dryhurst, S.; Schneider, C.R.; Kerr, J.; Freeman, A.L.J.; Recchia, G.; van der Bles, A.M.; Spiegelhalter, D.; van der Linden, S. Risk perceptions of COVID-19 around the world. J. Risk Res. 2020, 23, 994–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glockner, A.; Dorrough, A.; Wingen, T.; Dohle, S. The Perception of Infection Risks during the Early and Later Outbreak of COVID-19 in Germany: Consequences and Recommendations. In PsyArXiv. 2020. Available online: https://psyarxiv.com/wdbgc/ (accessed on 15 July 2021).

- Park, T.; Ju, I.; Ohs, J.E.; Hinsley, A. Optimistic bias and preventive behavioral engagement in the context of COVID-19. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2021, 17, 1859–1866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewer, N.T.; Chapman, G.B.; Gibbons, F.X.; Gerrard, M.; McCaul, K.D.; Weinstein, N.D. Meta-analysis of the relationship between risk perception and health behavior: The example of vaccination. Health Psychol. 2007, 26, 136–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Brewer, N.T.; Chapman, G.B.; Rothman, A.J.; Leask, J.; Kempe, A. Increasing Vaccination: Putting Psychological Science into Action. Psychol. Sci. Public Interest 2017, 18, 149–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Loewenstein, G.F.; Weber, E.U.; Hsee, C.K.; Welch, N. Risk as feelings. Psychol. Bull. 2001, 127, 267–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slovic, P.; Finucane, M.L.; Peters, E.; MacGregor, D.G. Risk as Analysis and Risk as Feelings: Some Thoughts about Affect, Reason, Risk, and Rationality. Risk Anal. 2004, 24, 311–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salleh, M.R. Life Event, Stress and Illness. Malays. J. Med. Sci. 2008, 15, 9–18. [Google Scholar]

- Mariotti, A. The effects of chronic stress on health: New insights into the molecular mechanisms of brain–body communication. Future Sci. OA 2015, 1, FSO23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

| Variables | Vaccinated (n = 179) | Planning to Be Vaccinated (n = 938) | Not Planning to Be Vaccinated (n = 428) | All Respondents (n = 1545) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Freq | % of Total | Freq | % of Total | Freq | % of Total | Freq | % of Total | |

| Gender | ||||||||

| Female | 43 | 24.02 | 184 | 19.62 | 99 | 23.13 | 326 | 21.10 |

| Male | 136 | 75.98 | 754 | 80.38 | 329 | 76.87 | 1219 | 78.90 |

| Aware of vaccine | ||||||||

| Now Aware | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 28 | 6.54 | 28 | 1.81 |

| Aware | 179 | 100.00 | 938 | 100.00 | 400 | 93.46 | 1517 | 98.19 |

| Age groups | ||||||||

| <25 | 7 | 3.91 | 75 | 8.00 | 52 | 12.15 | 134 | 8.67 |

| 25 < 35 | 34 | 18.99 | 244 | 26.01 | 132 | 30.84 | 410 | 26.54 |

| 35 < 45 | 46 | 25.70 | 276 | 29.42 | 110 | 25.70 | 432 | 27.96 |

| 445 < 55 | 39 | 21.79 | 160 | 17.06 | 63 | 14.72 | 262 | 16.96 |

| 55 < 65 | 31 | 17.32 | 110 | 11.73 | 41 | 9.58 | 182 | 11.78 |

| 65 and above | 22 | 12.29 | 73 | 7.78 | 30 | 7.01 | 125 | 8.09 |

| Medical services needed | ||||||||

| No | 100 | 55.87 | 542 | 57.78 | 248 | 57.94 | 890 | 57.61 |

| Yes | 79 | 44.13 | 396 | 42.22 | 180 | 42.06 | 655 | 42.39 |

| Worked last week | ||||||||

| No | 48 | 26.82 | 160 | 17.06 | 79 | 18.46 | 287 | 18.58 |

| Yes | 131 | 73.18 | 778 | 82.94 | 349 | 81.54 | 1258 | 81.42 |

| Worked during last survey | ||||||||

| No | 68 | 37.99 | 259 | 27.61 | 117 | 27.34 | 444 | 28.74 |

| Yes | 111 | 62.01 | 679 | 72.39 | 311 | 72.66 | 1101 | 71.26 |

| Variables | Vaccinated (n = 179) | Planning to Be Vaccinated (n = 938) | Not Planning to Be Vaccinated (n = 428) | All Respondents (n = 1545) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Freq | % of Total | Freq | % of Total | Freq | % of Total | Freq | % of Total | |

| Hand washing | ||||||||

| No hand washing or did not go out | 14 | 7.82 | 69 | 7.36 | 56 | 13.08 | 139 | 9.00 |

| Washed hands | 165 | 92.18 | 869 | 92.64 | 372 | 86.92 | 1406 | 91.00 |

| Mask wearing | ||||||||

| No mask wearing or did not go out | 11 | 6.15 | 88 | 9.38 | 66 | 15.42 | 165 | 10.68 |

| Wore masks | 168 | 93.85 | 850 | 90.62 | 362 | 84.58 | 1380 | 89.32 |

| COVID-19 and Health | ||||||||

| Very worried of having COVID-19 | 106 | 59.22 | 683 | 81.50 | 295 | 68.93 | 1084 | 70.16 |

| Somewhat worried of having COVID-19 | 28 | 15.64 | 110 | 13.13 | 36 | 8.41 | 174 | 11.26 |

| Not too worried of having COVID | 27 | 15.08 | 75 | 8.95 | 43 | 10.05 | 145 | 9.39 |

| Not worried at all of having COVID | 18 | 10.06 | 70 | 8.35 | 54 | 12.62 | 142 | 9.19 |

| COVID-19 and Finance | ||||||||

| COVID-19 is substantial threat to finance | 112 | 62.57 | 678 | 80.91 | 300 | 70.09 | 1090 | 70.55 |

| COVID-19 is moderate threat to finance | 29 | 16.20 | 132 | 15.75 | 61 | 14.25 | 222 | 14.37 |

| COVID-19 is not much threat to finance | 26 | 14.53 | 86 | 10.26 | 48 | 11.21 | 160 | 10.36 |

| COVID-19 is not threat at all to finance | 12 | 6.70 | 42 | 5.01 | 19 | 4.44 | 73 | 4.72 |

| Variables | Vaccinated (n = 179) | Planning to Be Vaccinated (n = 938) | Not Planning to Be Vaccinated (n = 428) | All Respondents (n = 1545) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COVID-19 and Health | Freq | % of Total | Freq | % of Total | Freq | % of Total | Freq | % of Total |

| Little interest or pleasure in doing things | ||||||||

| No | 142 | 79.33 | 656 | 78.28 | 318 | 74.30 | 1116 | 72.23 |

| Yes | 37 | 20.67 | 282 | 33.65 | 110 | 25.70 | 429 | 27.77 |

| Feeling down, depressed, or hopeless | ||||||||

| No | 126 | 70.39 | 615 | 73.39 | 289 | 67.52 | 1030 | 66.67 |

| Yes | 53 | 29.61 | 323 | 38.54 | 139 | 32.48 | 515 | 33.33 |

| Trouble falling or staying asleep, or sleeping too much | ||||||||

| No | 132 | 73.74 | 684 | 81.62 | 340 | 79.44 | 1156 | 74.82 |

| Yes | 47 | 26.26 | 254 | 30.31 | 88 | 20.56 | 389 | 25.18 |

| Feeling tired or having little energy | ||||||||

| No | 129 | 72.07 | 622 | 74.22 | 280 | 65.42 | 1031 | 66.73 |

| Yes | 50 | 27.93 | 316 | 37.71 | 148 | 34.58 | 514 | 33.27 |

| Poor appetite or overeating | ||||||||

| No | 147 | 82.12 | 761 | 90.81 | 357 | 83.41 | 1265 | 81.88 |

| Yes | 32 | 17.88 | 177 | 21.12 | 71 | 16.59 | 280 | 18.12 |

| Feeling bad about yourself/or that you’re a failure/have let yourself or family | ||||||||

| No | 134 | 74.86 | 630 | 75.18 | 283 | 66.12 | 1047 | 67.77 |

| Yes | 45 | 25.14 | 308 | 36.75 | 145 | 33.88 | 498 | 32.23 |

| Trouble concentrating on things, such as reading the newspaper/watching TV | ||||||||

| No | 145 | 81.01 | 786 | 93.79 | 365 | 85.28 | 1296 | 83.88 |

| Yes | 34 | 18.99 | 152 | 18.14 | 63 | 14.72 | 249 | 16.12 |

| Moving or speaking so slowly/or fast that other people could have noticed? | ||||||||

| No | 152 | 84.92 | 795 | 94.87 | 380 | 88.79 | 1327 | 85.89 |

| Yes | 27 | 15.08 | 143 | 17.06 | 48 | 11.21 | 218 | 14.11 |

| Variables | Vaccinated (Model 1) | Positive Vaccine Intention and Vaccinated (Model 2) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient | Std. Err. | Z Stat | Coefficient | Std. Err. | Z Stat | |

| Demographic/health | ||||||

| Stress index | −0.3117178 *** | 0.0535994 | −5.82 | −0.1020463 * | 0.058470 | −1.75 |

| Gender of household head | −0.0564463 | 0.0961462 | −0.59 | 0.1172023 | 0.083045 | 1.41 |

| Age of the household head | 0.011972 *** | 0.0028735 | 4.17 | 0.0087886 *** | 0.002505 | 3.51 |

| Medical services needed | 0.3180021 *** | 0.0908427 | 3.50 | 0.0887663 | 0.0836925 | 1.06 |

| Employed during last survey | −0.2675059 *** | 0.0850981 | −3.14 | −0.0880712 | 0.0769721 | −1.14 |

| Risk perception | ||||||

| Worried family contracts COVID | 0.2285566 * | 0.1256379 | 1.82 | 0.1960976 * | 0.1197572 | 1.64 |

| Not too worried family contracts COVID | 0.3229509 ** | 0.133186 | 2.42 | −0.0891405 | 0.1229729 | −0.72 |

| Not worried at all family contracts COVID | 0.0659449 | 0.1467924 | 0.45 | −0.3235615 ** | 0.1237355 | −2.61 |

| Finance moderately threatened by COVID | −0.135423 | 0.120778 | −1.12 | −0.0751409 | 0.1060315 | −0.71 |

| Finance not much threatened by COVID | −0.0281268 | 0.1361904 | −0.21 | −0.0878501 | 0.1236292 | −0.71 |

| Finance not threatened at all by COVID | 0.0995716 | 0.1846589 | 0.54 | 0.1537056 | 0.173889 | 0.88 |

| Protective behaviour | ||||||

| Hand washing | −0.2759615 | 0.1826417 | −1.51 | 0.1598855 | 0.1428438 | 1.12 |

| Mask wearing | 0.450405 ** | 0.1896148 | 2.38 | 0.2829097 ** | 0.1314992 | 2.15 |

| Constant | −1.701197 *** | 0.2460611 | −6.91 | −0.2144785 | 0.179874 | −1.19 |

| Diagnostic indicators | ||||||

| Athrho | 0.5450511 *** | 0.1170509 | 4.66 | 0.235604 ** | 0.1015182 | 2.32 |

| Lnsigma | 0.4562054 *** | 0.0179896 | 25.36 | 0.4562053 *** | 0.0179896 | 25.36 |

| Rho | 0.4968019 | 0.0881613 | 0.2313392 | 0.0960852 | ||

| Sigma | 1.578074 | 0.0283889 | 1.578074 | 0.0283889 | ||

| Number of obs | 1545 | 1545 | ||||

| Wald Chi Square (13) | 98.03 *** | 46.87 *** | ||||

| Log likelihood | −3416.39 | −3783.771 | ||||

| Wald test of exogeneity | 21.68 *** | 5.39 ** | ||||

| VIF | 1.18 | 1.18 | ||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Oyekale, A.S.; Maselwa, T.C. An Instrumental Variable Probit Modeling of COVID-19 Vaccination Compliance in Malawi. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 13129. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182413129

Oyekale AS, Maselwa TC. An Instrumental Variable Probit Modeling of COVID-19 Vaccination Compliance in Malawi. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(24):13129. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182413129

Chicago/Turabian StyleOyekale, Abayomi Samuel, and Thonaeng Charity Maselwa. 2021. "An Instrumental Variable Probit Modeling of COVID-19 Vaccination Compliance in Malawi" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 24: 13129. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182413129

APA StyleOyekale, A. S., & Maselwa, T. C. (2021). An Instrumental Variable Probit Modeling of COVID-19 Vaccination Compliance in Malawi. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(24), 13129. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182413129