Does Basic Psychological Need Satisfaction Matter to College Students’ Sustained Volunteering? A Mixed-Methods Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Theoretical Framework

2.1. Self-Determination Theory in Volunteering

2.2. Basic Psychological Need Satisfaction and Sustained Volunteering

2.2.1. From a Variable-Centered Perspective

2.2.2. From a Person-Centered Perspective

2.2.3. Mixed-Methods Approach

3. The Current Study

4. Methods in Quantitative Phase

4.1. Participants and Procedure

4.2. Measures

4.3. Statistical Analysis

5. Results in Quantitative Phase

5.1. Analysis Results of Variable-Centered

5.2. Analysis Results of Person-Centered

5.2.1. Profiles of Three BPNS

5.2.2. Profiles Differences in Sustained Volunteering

6. Methods in Qualitative Phase

6.1. Participants and Procedure

6.2. Interview Questions

6.3. Data Analysis

7. Results of Qualitative Phase

7.1. Emphasizing the Satisfaction of Competence and Relatedness Needs

7.2. Low but Indispensable Autonomy Need Satisfaction

8. Discussion

8.1. Three BPNS and Sustained Volunteering: From Variable- and Person-Centered Perspective

8.2. An Integrated Perspective of Quantitative and Qualitative Stages

9. Limitations and Future Research

10. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Penner, L.A. Dispositional and organizational influences on sustained volunteerism: An interactionist perspective. J. Soc. Issues 2002, 58, 447–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhanot, S.P.; Crost, B.; Leight, J.; Mvukiyehe, E.; Yedgenov, B. Can community service grants foster social and economic integration for youth? A randomized trial in Kazakhstan. J. Dev. Econ. 2021, 153, 102718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyde, M.K.; Dunn, J.; Bax, C.; Chambers, S.K. Episodic volunteering and retention: An integrated theoretical approach. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Q. 2016, 45, 45–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kramer, M.W.; Austin, J.T.; Hansen, G.J. Toward a model of the influence of motivation and communication on volunteering: Expanding self-determination theory. Manag. Commun. Q. 2021, 35, 572–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vecina, M.L.; Poy, S.; Benevene, P.; Marzana, D. The subjective index of benefits in volunteering (sibiv): An instrument to manage satisfaction and permanence in non-profit organizations. Curr. Psychol. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, F.F.; Li, Y.L.; Wang, C.; Zong, X.L.; Yao, M.L.; Yan, W.F. Service participation among adolescents in Mainland China. J. Soc. Serv. Res. 2020, 46, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veludo-de-Oliveira, T.; Pallister, J.G.; Foxall, G.R. Accounting for sustained volunteering by young people: An expanded TPB. Voluntas 2013, 24, 1180–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Harp, E.R.; Scherer, L.L.; Allen, J.A. Volunteer engagement and retention: Their relationship to community service self-efficacy. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Q. 2017, 46, 442–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullan, B.; Liddelow, C.; Charlesworth, J.; Slabbert, A.; Allom, V.; Harris, C.; Same, A.; Kothe, E. Investigating mechanisms for recruiting and retaining volunteers: The role of habit strength and planning in volunteering engagement. J. Soc. Psychol. 2021, 161, 363–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aydinli, A.; Bender, M.; Chasiotis, A.; Van de Vijver, F.J.R.; Cemalcilar, Z.; Chong, A.; Yue, X.D. A cross-cultural study of explicit and implicit motivation for long-term volunteering. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Q. 2016, 45, 375–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydinli-Karakulak, A.; Bender, M.; Chong, A.M.L.; Yue, X. Applying western models of volunteering in Hong Kong: The role of empathy, prosocial motivation and motive-experience fit for volunteering. Asian J. Soc. Psychol. 2016, 19, 112–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boezeman, E.J.; Ellemers, N. Intrinsic need satisfaction and the job attitudes of volunteers versus employees working in a charitable volunteer organization. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2009, 82, 897–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haivas, S.; Hofmans, J.; Pepermans, R. Volunteer engagement and intention to quit from a self-determination theory perspective. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2013, 43, 1869–1880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. Intrinsic Motivation and Self Determination in Human Behavior; Plenum: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. The ‘‘what’’ and ‘‘why’’ of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychol. Inq. 2000, 11, 227–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- China Youth. Introduction to Projects of Voluntary Services of College Students in the “Go West Program”. Available online: http://xibu.youth.cn/xmjs/201510/t20151015_7212132.htm (accessed on 3 May 2018).

- Yao, M.L.; Guo, F.F. Service-learning in China: The realistic demand and promoting strategies. J. Beijing Nor. Univ. 2015, 3, 51–58. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston, M.M.; Finney, S.J. Measuring basic needs satisfaction: Evaluating previous research and conducting new psychometric evaluations of the basic needs satisfaction in general scale. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2010, 35, 280–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. Levels of analysis, regnant causes of behavior and well-being: The role of psychological needs. Psychol. Inq. 2011, 22, 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagne, M. The role of autonomy support and autonomy orientation in prosocial behavior engagement. Motiv. Emot. 2003, 27, 199–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haski-Leventhal, D.; Kach, A.; Pournader, M. Employee need satisfaction and positive workplace outcomes: The role of corporate volunteering. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Q. 2019, 48, 593–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Park, C.; Kim, H.; Kim, J. Determinants and outcomes of volunteer satisfaction in mega sports events. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kwok, Y.Y.; Chui, W.H.; Wong, L.P. Need satisfaction mechanism linking volunteer motivation and life satisfaction: A mediation study of volunteers subjective well-being. Soc. Indic. Res. 2013, 114, 1315–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, D.J.; Curran, P.J. The integration of continuous and discrete latent variable models: Potential problems and promising opportunities. Psychol. Methods 2004, 9, 3–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Meyer, J.P.; Morin, A.J.S. A person-centered approach to commitment research: Theory, research, and methodology. J. Organ. Behav. 2016, 37, 584–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Huang, Y.; Bortree, D.S.; Yang, F.; Wang, R.X. Encouraging volunteering in nonprofit organizations: The role of organizational inclusion and volunteer need satisfaction. J. Nonprofit Public Sect. Market. 2020, 32, 147–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kackar-cam, H.; Schmidt, J.A. Community-based service-learning as a context for youth autonomy, competence, and relatedness. High Sch. J. 2014, 98, 83–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavey, L.; Greitemeyer, T.; Sparks, P. Highlighting relatedness promotes prosocial motives and behavior. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2011, 37, 905–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Finkelstein, M.A. Individualism/Collectivism: Implications for the volunteer process. Soc. Behav. Pers. 2010, 38, 445–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finkelstein, M.A. Correlates of individualism and collectivism: Predicting volunteer activity. Soc. Behav. Pers. 2011, 39, 597–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.S.; Schmitt, M.; Zhou, C.; Nartova-Bochaver, S.; Astanina, N.; Khachatryan, N.; Han, B.X. Examining self-advantage in the suffering of others: Cross-cultural differences in beneficiary and observer justice sensitivity among Chinese, Germans, and Russians. Soc. Justice Res. 2014, 27, 231–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, G.P.; Garris, C.P.; Aldamer, S. Individualism behind collectivism: A reflection from Saudi volunteers. Voluntas 2018, 29, 144–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, L.P.; Chui, W.H.; Kwok, Y.Y. The volunteer satisfaction index: A validation study in the Chinese cultural context. Soc. Indic. Res. 2011, 104, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Khasanzyanova, A. How volunteering helps students to develop soft skills. Int. Rev. Educ. 2017, 63, 363–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milbourn, B.; Black, M.H.; Buchanan, A. Why people leave community service organizations: A mixed methods Study. Voluntas 2019, 30, 272–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillet, N.; Morin, A.J.S.; Choisay, F.; Fouquereau, E. A person-centered representation of basic need satisfaction balance at work. J. Pers. Psychol. 2019, 18, 113–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillet, N.; Morin, A.J.; Huyghebaert-Zouaghi, T.; Alibran, E.; Barrault, S.; Vanhove-Meriaux, C. Students’ need satisfaction profiles: Similarity and change over the course of a university Semester. Appl. Rev. Int. 2020, 69, 1396–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrand, C.; Martinent, G.; Durmaz, N. Psychological need satisfaction and well-being in adults aged 80 years and older living in residential homes: Using a self-determination theory perspective. J. Aging Stud. 2014, 30, 104–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esdar, W.; Gorges, J.; Wild, E. The role of basic need satisfaction for junior academics’ goal conflicts and teaching motivation. High. Educ. 2016, 72, 175–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Earl, S.R.; Taylor, A.M.; Meijen, C.; Passfield, L. Young adolescent psychological need profiles: Associations with classroom achievement and well-being. Psychol. Sch. 2019, 56, 1004–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souesme, G.; Martinent, G.; Ferrand, C. Perceived autonomy support, psychological needs satisfaction, depressive symptoms and apathy in French hospitalized older people. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2016, 65, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raiziene, S.; Gabrialaviciute, I.; Garckija, R. Links between basic psychological need satisfaction and school adjustment: A person-oriented approach. J. Psychol. Educ. Res. 2017, 25, 82–92. [Google Scholar]

- Reznickova, A.; Zepeda, L. Can self-determination theory explain the self-perpetuation of social innovations? A case study of slow food at the university of Wisconsin Madison. J. Community Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2016, 26, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podlog, L.; Dionigi, R.A. Psychological need fulfillment among workers in an exercise intervention: A qualitative investigation. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport. 2009, 80, 774–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thoits, P.A.; Hewitt, L.N. Volunteer work and well-being. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2001, 42, 115–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muthén, L.K.; Muthén, B.O. Mplus Statistical Analysis with Latent Variables, User’s Guide; Muthén & Muthén: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, J.Y.; Lee, E. Reducing confusion about grounded theory and qualitative content analysis: Similarities and differences. Qual. Rep. 2014, 19, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Yao, M.; Liu, H.; Zheng, S. The effect of functional motivation on future intention to donate blood: Moderating role of the blood donor’s stage. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vansteenkiste, M.; Ryan, R.M.; Soenens, B. Basic psychological need theory: Advancements, critical themes, and future directions. Motiv. Emot. 2020, 44, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wu, Y.D.; Li, C.X.; Khoo, S. Predicting future volunteering intentions through a self-determination theory perspective. Voluntas 2016, 27, 1266–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, J.; Wilson, J. Volunteer work and hedonic, eudemonic, and social well-being. Sociol. Forum 2012, 27, 658–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Feng, L.; Zhang, L. Prosocial tendencies and subjective well-being: The mediating role of basic psychological needs satisfaction. Soc. Behav. Pers. 2021, 49, 9986–9995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nalipay, M.J.N.; King, R.B.; Cai, Y. Autonomy is equally important across East and West: Testing the cross-cultural universality of self-determination theory. J. Adolesc. 2020, 78, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables | Service Length | Service Frequency | Objective a | Subjective b | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | t | β | t | β | t | β | t | |

| Gender | 0.08 | 1.01 | −0.06 | −0.75 | 0.01 | 0.14 | 0.13 | 1.85 |

| Age | −0.11 | −5.00 *** | −0.10 | −4.43 *** | −0.10 | −5.43 *** | 0.01 | 0.49 |

| Autonomy | −0.01 | −0.33 | −0.01 | −0.19 | −0.01 | −0.30 | −0.02 | −0.74 |

| Relatedness | 0.08 | 0.90 | −0.03 | −0.33 | 0.02 | 0.32 | 0.41 | 5.39 *** |

| Competence | 0.21 | 2.73 ** | 0.23 | 2.99 ** | 0.22 | 3.29 ** | 0.34 | 4.93 *** |

| R2 | 0.07 *** | 0.05 *** | 0.07 *** | 0.25 *** | ||||

| Adjusted R2 | 0.06 *** | 0.04 *** | 0.07 *** | 0.25 *** | ||||

| F | 11.45 *** | 7.60 *** | 12.16 *** | 53.01 *** | ||||

| Variables | Profile 1 (a) | Profile 2 (b) | Profile 3 (c) | Profile 4 (d) | Profile 5 (e) | F | ηp2 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |||

| Profile variables | ||||||||||||

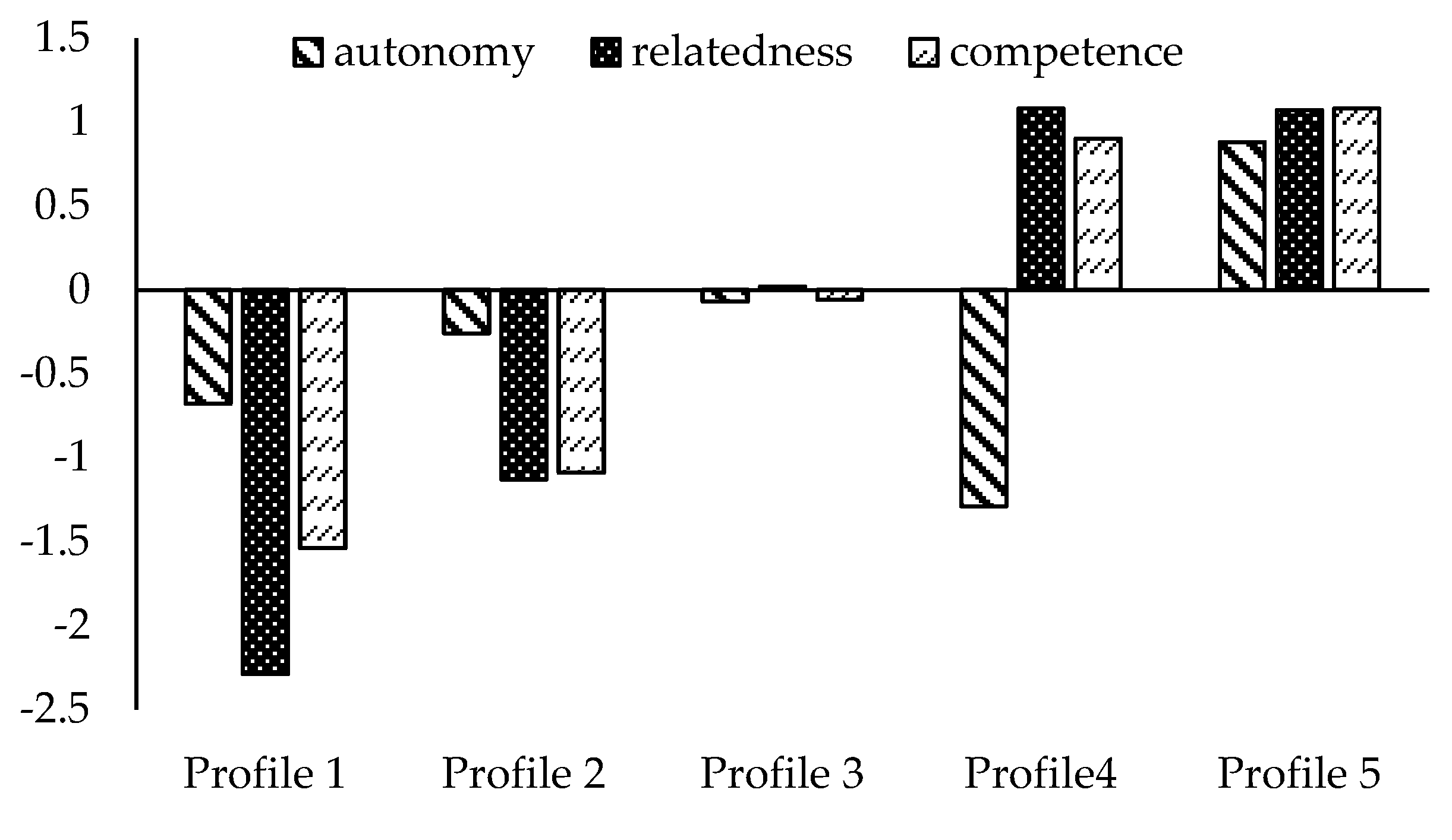

| Autonomy | −0.68 bcde | 0.78 | −0.26 ade | 0.82 | −0.07 ade | 0.90 | −1.29 abce | 0.62 | 0.88 abcd | 0.67 | 106.79 *** | 0.35 |

| Relatedness | −2.29 bcde | 0.46 | −1.13 acde | 0.37 | 0.02 abde | 0.36 | 1.08 abc | 0.29 | 1.07 abc | 0.32 | 1423.16 *** | 0.71 |

| Competence | −1.54 bcde | 0.66 | −1.09 acde | 0.55 | −0.06 abde | 0.56 | 0.90 abc | 0.54 | 1.08 abc | 0.49 | 482.82 *** | 0.88 |

| Outcome variables | ||||||||||||

| Service length | 62.16 d | 66.67 | 59.94 de | 57.36 | 72.74 d | 62.85 | 99.00 abc | 70.37 | 86.24 b | 67.37 | 6.54 *** | 0.03 |

| Service frequency | 2.70 | 1.33 | 2.71 e | 1.11 | 2.88 | 1.21 | 3.17 | 1.29 | 3.07 b | 1.37 | 2.89 * | 0.01 |

| Objective | −0.18 | 0.93 | −0.19 de | 0.76 | −0.02 | 0.85 | 0.29 b | 0.94 | 0.16 b | 0.94 | 5.92 *** | 0.03 |

| Subjective | 4.65 bcde | 1.12 | 5.35 acde | 1.00 | 5.90 abde | 0.83 | 6.42 abc | 0.75 | 6.33 abc | 0.89 | 50.37 *** | 0.20 |

| Categories and Subcategories | Frequencies of Categories | Frequencies of Subcategories |

|---|---|---|

| Category 1: Autonomy need satisfaction | 14.68% | |

| voluntary (not required) participation in volunteer service | 6.42% | |

| feelings of high autonomy | 8.26% | |

| Category 2: Competence need satisfaction | 47.25% | |

| acquire new knowledge and experience/develop skills | 17.89% | |

| a sense of value/meaning | 15.14% | |

| a sense of accomplishment and competence | 11.93% | |

| experience a challenge in difficult tasks | 2.29% | |

| Category 3: Relatedness need satisfaction | 30.73% | |

| build relationships with others (such as recipients, teammates, members of voluntary service organizations) | 19.72% | |

| positive volunteer peer relationships | 5.50% | |

| a sense of belonging | 3.21% | |

| accompanied by friends | 1.38% | |

| teamwork | 0.92% |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zheng, S.; Yao, M.; Zhang, L.; Li, J.; Xing, H. Does Basic Psychological Need Satisfaction Matter to College Students’ Sustained Volunteering? A Mixed-Methods Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 13229. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182413229

Zheng S, Yao M, Zhang L, Li J, Xing H. Does Basic Psychological Need Satisfaction Matter to College Students’ Sustained Volunteering? A Mixed-Methods Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(24):13229. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182413229

Chicago/Turabian StyleZheng, Shuang, Meilin Yao, Lifan Zhang, Jing Li, and Huilin Xing. 2021. "Does Basic Psychological Need Satisfaction Matter to College Students’ Sustained Volunteering? A Mixed-Methods Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 24: 13229. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182413229