Influencing Factors of Public Satisfaction with COVID-19 Prevention Services Based on Structural Equation Modeling (SEM): A Study of Nanjing, China

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

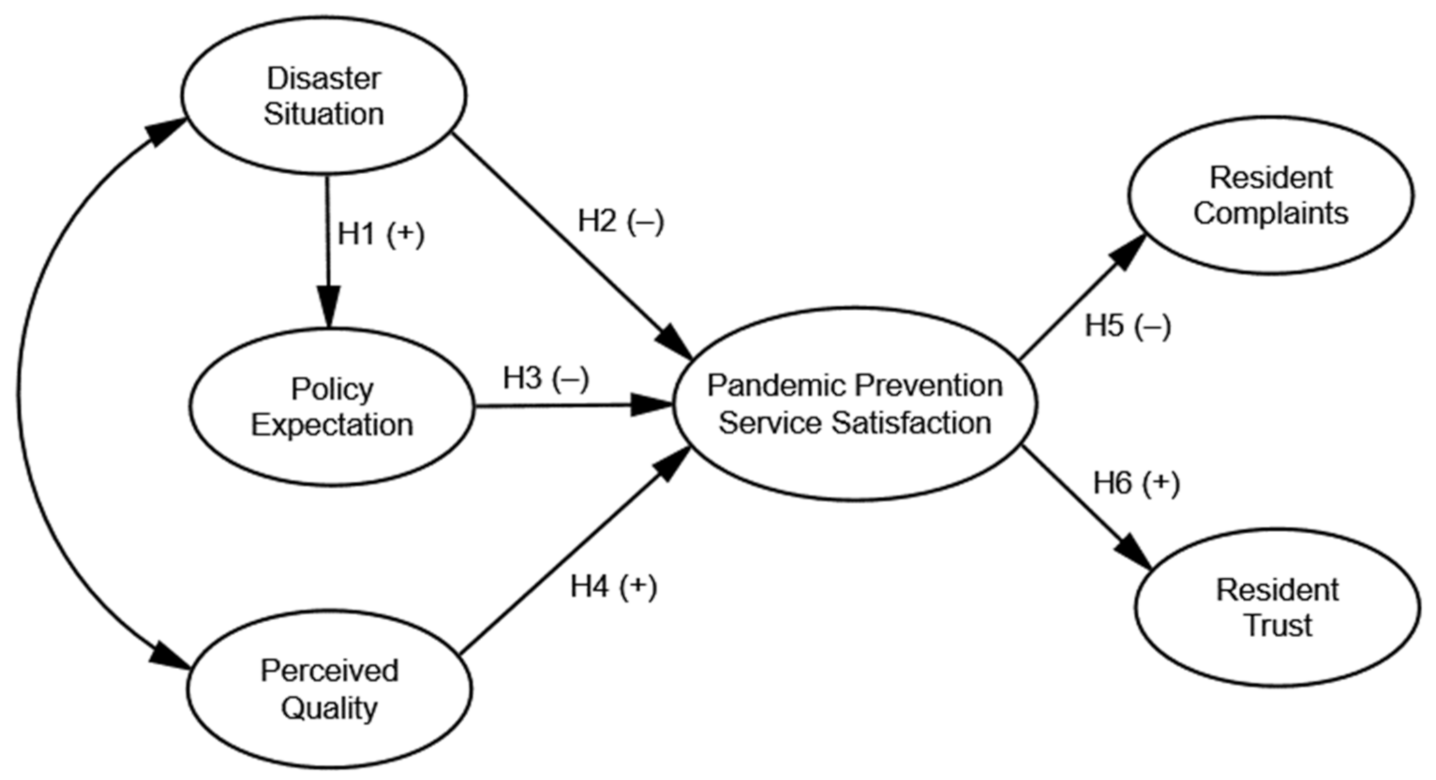

2.1. Theoretical Hypotheses

2.2. Methods

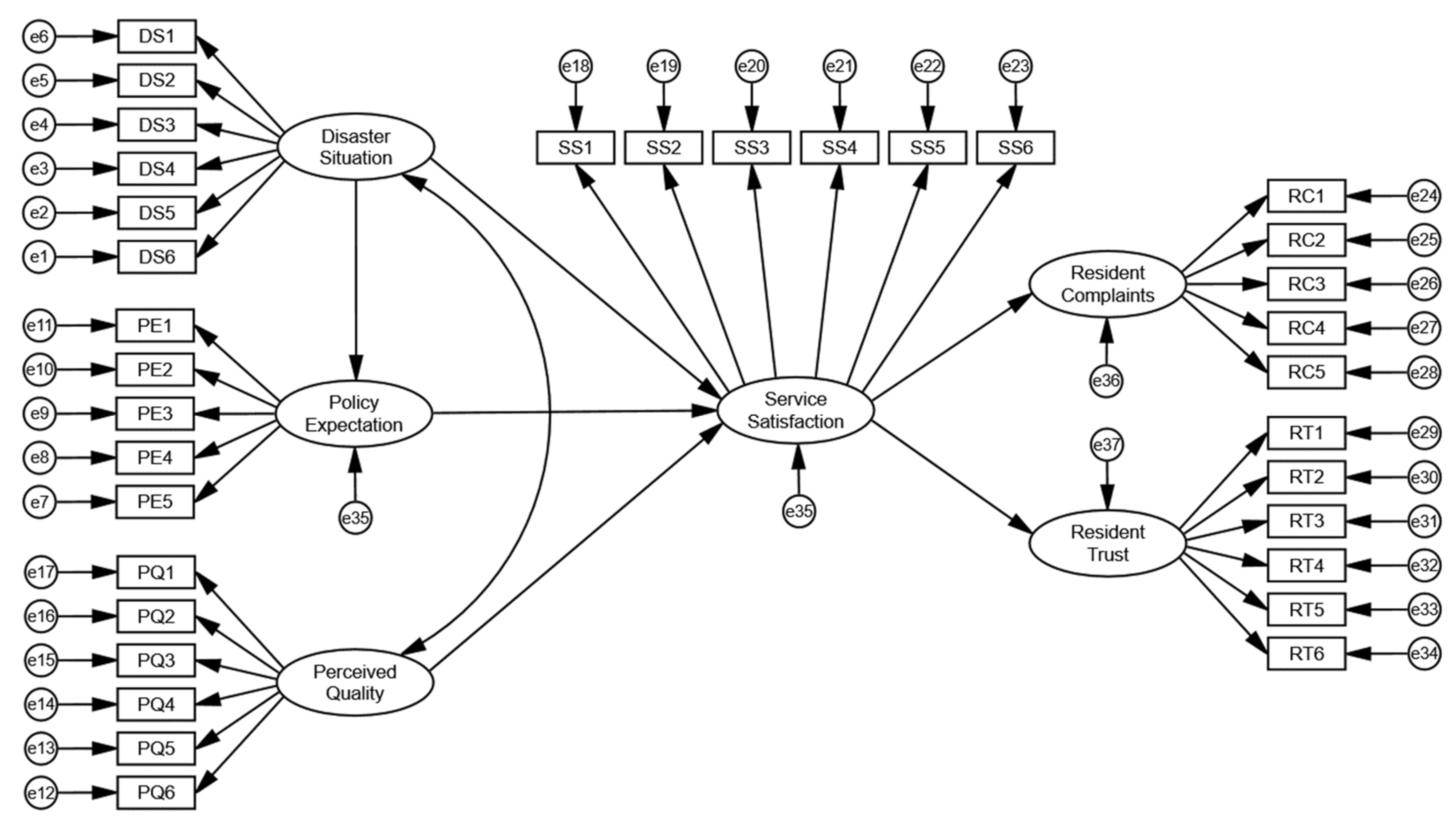

2.2.1. Variables and Structural Equation Modeling

2.2.2. Data Collection and Processing

3. Results

3.1. Effective Questionnaire Screening and Descriptive Statistics

3.2. Reliability and Validity Testing

3.3. Hypothesis Testing and Impact Effect between the Factors

4. Discussion and Limitations

5. Conclusions and Implications

5.1. Conclusions

5.2. Practical Implications

- (1)

- The professionalism of pandemic prevention policies and the action capacity of the relevant departments should be enhanced. Professional knowledge represents professionalism; thus, policies can be made feasible by being supported by sufficient expertise. In similar public health incidents, doctors, researchers, and scholars in related fields are not only personnel with sufficient professional knowledge, but are also individuals trusted by the public. In the process of the government issuing relevant policies and response measures, personnel with sufficient professional knowledge and professional discourse power should conduct supervision, guidance, and policy evaluation. The action capacity shows the efficiency of policy formulation and the speed of action by relevant departments. A strong action capacity can make the public have confidence in epidemic prevention and trust in the pandemic prevention services provided by the government.

- (2)

- The propaganda and popularization of relevant basic knowledge of pandemic prevention and basic pandemic information should be strengthened. The main PQ factors affecting residents’ satisfaction with pandemic prevention services were found to be “I understand how COVID-19 spreads,” “I understand the infectiousness of COVID-19,” “I can identify which type of mask is suitable for preventing COVID-19,” and “I understand the number of infected people and the distribution of the hardest-hit areas”; in view of this, when similar public health incidents occur, focus should be placed on strengthening the publicity and popularization of the infectivity of the disease, relevant protective measures, and the distribution of the hardest-hit areas. The publicity of various types of basic pandemic prevention information should be detailed to communities and residential areas, and community WeChat groups, official accounts, and SMS point-to-point distribution must be fully utilized; this will allow residents to learn about pandemic-related information in a timely and convenient manner.

- (3)

- Attention should be paid to the changes in the psychological state of residents during the pandemic, and psychological counseling for the public should be strengthened. Considering that “The extent to which my psychological state has been affected by the pandemic” was found to significantly affect residents’ satisfaction with pandemic prevention, the changes in residents’ psychological state during a pandemic period deserve more attention. At present, most of the psychological counseling work for residents during the pandemic period has been via text or video chat, which has not played an effective role. The community must gradually establish a complete psychological counseling service process and establish a psychological counseling service station. Personnel with professional psychology knowledge can provide community residents with a face-to-face communication platform to protect residents’ psychological safety during a pandemic.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Observed Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PQ1 | 0.774 | |||||

| PQ2 | 0.784 | |||||

| PQ3 | 0.745 | |||||

| PQ4 | 0.768 | |||||

| PQ5 | 0.757 | |||||

| PQ6 | 0.761 | |||||

| DS1 | 0.794 | |||||

| DS2 | 0.789 | |||||

| DS3 | 0.77 | |||||

| DS4 | 0.814 | |||||

| DS5 | 0.786 | |||||

| DS6 | 0.81 | |||||

| PE1 | 0.753 | |||||

| PE2 | 0.734 | |||||

| PE3 | 0.762 | |||||

| PE4 | 0.778 | |||||

| PE5 | 0.773 | |||||

| SS1 | 0.77 | |||||

| SS2 | 0.778 | |||||

| SS3 | 0.742 | |||||

| SS4 | 0.783 | |||||

| SS5 | 0.741 | |||||

| SS6 | 0.775 | |||||

| RC1 | 0.795 | |||||

| RC2 | 0.841 | |||||

| RC3 | 0.796 | |||||

| RC4 | 0.786 | |||||

| RC5 | 0.811 | |||||

| RT1 | 0.779 | |||||

| RT2 | 0.765 | |||||

| RT3 | 0.78 | |||||

| RT4 | 0.783 | |||||

| RT5 | 0.794 | |||||

| RT6 | 0.788 | |||||

| Eigenvalue | 3.126 | 7.978 | 2.013 | 2.609 | 2.328 | 4.052 |

| Variance contribution rate | 9.19% | 23.46% | 5.92% | 7.67% | 6.85% | 11.92% |

| Total variance contribution rate | 65.02% | |||||

Appendix B

References

- World Health Organization (WHO). World Health Statistics 2021. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/342703/9789240027053-eng.pdf (accessed on 18 July 2021).

- Qi, Y.; Du, C.D.; Liu, T.; Zhao, X.; Dong, C. Experts’ conservative judgment and containment of COVID-19 in early outbreak. J. Chin. Gov. 2020, 5, 140–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- French, P.E. Enhancing the legitimacy of local government pandemic influenza planning through transparency and public engagement. Public Adm. Rev. 2011, 71, 253–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voogd, R.; de Vries, J.R.; Beunen, R. Understanding public trust in water managers: Findings from the Netherlands. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 300, 113749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dou, M.; Gu, Y.; Xu, G. Social awareness of crisis events: A new perspective from social-physical network. Cities 2020, 99, 102620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iglesias-Sánchez, P.P.; Vaccaro Witt, G.F.; Cabrera, F.E.; Jambrino-Maldonado, C. The contagion of sentiments during the COVID-19 pandemic crisis: The case of isolation in Spain. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Developing a COVID-19 Crisis Management Strategy Using News Media and Social Media in Big Data Analytics. Available online: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/08944393211007314 (accessed on 15 October 2021).

- Song, J.; Song, T.M. Social big-data analysis of particulate matter, health, and society. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Maciejewski, M. To do more, better, faster and more cheaply: Using big data in public administration. Int. Rev. Adm. Sci. 2017, 83, 120–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lin, M. Influencing factors of social service satisfaction of the elderly under the background of internet attention. Complexity 2021, 2021, 9985280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalski, R.; Esteve, M.; Jankin Mikhaylov, S. Improving public services by mining citizen feedback: An application of natural language processing. Public Adm. 2020, 98, 1011–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fournier, S.; Mick, D.G. Rediscovering satisfaction. J. Mark. 1999, 63, 5–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szymanski, D.M.; Henard, D.H. Customer satisfaction: A meta-analysis of the empirical evidence. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2001, 29, 16–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veenhoven, R. Developments in satisfaction-research. Soc. Indic. Res. 1996, 37, 1–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Job Satisfaction among Occupational Therapy Practitioners: A Systematic Review of Quantitative Studies. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34407737/ (accessed on 15 October 2021).

- Liu, Y.; Wan, Y.; Shen, X.; Ye, Z.; Wen, J. Product customer satisfaction measurement based on multiple online consumer review features. Information 2021, 12, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.R.; Petrick, J.F. Towards an integrative model of loyalty formation: The role of quality and value. Leis. Sci. 2010, 32, 201–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Johnson, M.D.; Anderson, E.W.; Cha, J.; Bryant, B.E. The American customer satisfaction index: Nature, purpose, and findings. J. Mark. 1996, 60, 7–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- HSU, S. Developing an index for online customer satisfaction: Adaptation of American Customer Satisfaction Index. Expert Syst. Appl. 2008, 34, 3033–3042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Ryzin, G.G.; Muzzio, D.; Immerwahr, S.; Gulick, L.; Martinez, E. Drivers and Consequences of Citizen Satisfaction: An Application of the American Customer Satisfaction Index Model to New York City. Public Adm. Rev. 2004, 64, 331–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Liu, Y.; Lu, W.; Xiao, G. Evaluating passenger satisfaction index based on PLS-SEM model: Evidence from Chinese public transport service. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2019, 120, 149–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kar, A.K. What affects usage satisfaction in mobile payments? Modelling user generated content to develop the “digital service usage satisfaction model”. Inf. Syst. Front. 2020, 23, 1341–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilyas, G.B.; Rahmi, S.; Tamsah, H.; Munir, A.R.; Putra, A.H.P.K. Reflective model of brand awareness on repurchase intention and customer satisfaction. J. Asian Financ. Econ. Bus. 2020, 7, 427–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumiadji; Handoyo, F.; Setiati, F. Servive Quality on Education Institution: Satisfaction Index and IPA (Case Study on Accounting Department of State Polytechnic of Malang. Int. J. Soc. Sci. Bus. 2019, 3, 549–556. [Google Scholar]

- Van de Walle, S.; Van Roosbroek, S.; Bouckaert, G. Trust in the public sector: Is there any evidence for a long-term decline? Int. Rev. Adm. Sci. 2008, 74, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gruening, G. Origin and theoretical basis of new public management. Int. Public Manag. J. 2001, 4, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denhardt, R.B.; Denhardt, J.V. The new public service: Serving rather than steering. Public Adm. Rev. 2000, 60, 549–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, R.; Van de Walle, S. New public management and citizens’ perceptions of local service efficiency, responsiveness, equity and effectiveness. Public Manag. Rev. 2013, 15, 762–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritz, A.; Brewer, G.A.; Neumann, O. Public service motivation: A systematic literature review and outlook. Public Adm. Rev. 2016, 76, 414–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhee, S.K.; Rha, J.Y. Public service quality and customer satisfaction: Exploring the attributes of service quality in the public sector. Serv. Ind. J. 2009, 29, 1491–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kampen, J.K.; Van De Walle, S.; Bouckaert, G. Assessing the Relation Between Satisfaction with Public Service Delivery and Trust in Government. Public Perform. Manag. Rev. 2006, 29, 387–404. [Google Scholar]

- Mbassi, J.C.; Mbarga, A.D.; Ndeme, R.N. Public service quality and citizen-client’s satisfaction in local municipalities. J. Mark. Dev. Compet. 2019, 13, 110–123. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, W. Does Citizens’ 311 System Use Improve Satisfaction with Public Service Encounters? Lessons for Citizen Relationship Management. Int. J. Public Adm. 2021, 44, 665–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Understanding the Role Reward Types Play in Linking Public Service Motivation to Task Satisfaction: Evidence from an Experiment in China. Available online: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/10967494.2021.1963891 (accessed on 18 October 2021).

- Engdaw, B.D. The impact of quality public service delivery on customer satisfaction in Bahir Dar city administration: The case of Ginbot 20 Sub-city. Int. J. Public Adm. 2020, 43, 644–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ming, C.; Chen, T.; Ai, Q. An empirical study of E-service quality and user satisfaction of public service centers in China. Int. J. Public Adm. Digit. Age 2018, 5, 43–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lanin, D.; Hermanto, N. The effect of service quality toward public satisfaction and public trust on local government in Indonesia. Int. J. Soc. Econ. 2019, 46, 377–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitsios, F.; Kamariotou, M.; Karanikolas, P.; Grigoroudis, E. Digital marketing platforms and customer satisfaction: Identifying eWOM using big data and text mining. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 8032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clements, J.M. Knowledge and behaviors toward COVID-19 among us residents during the early days of the pandemic: Cross-sectional online questionnaire. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2020, 6, e19161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, A.; Ranjan, P.; Vikram, N.K.; Kaur, D.; Sahu, A.; Dwivedi, S.N.; Baitha, U.; Goel, A. A short questionnaire to assess changes in lifestyle-related behaviour during COVID 19 pandemic. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Clin. Res. Rev. 2020, 14, 1697–1701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Güner, R.; Hasanoğlu, I.; AKTAŞ, F. COVID-19: Prevention and control measures in community. Turk. J. Med. Sci. 2020, 50, 571–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Zhao, Y.; Li, Y.; Hu, C.; Xu, H.; Zhao, X.; Huang, J. Factors associated with job satisfaction of frontline medical staff fighting against COVID-19: A cross-sectional study in China. Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deriba, B.S.; Geleta, T.A.; Beyane, R.S.; Mohammed, A.; Tesema, M.; Jemal, K. Patient satisfaction and associated factors during COVID-19 pandemic in North Shoa health care facilities. Patient Prefer. Adherence 2020, 14, 1923–1934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wuneh, A.; Kahsay, A.; Tinsae, F.; Ashebir, F.; Giday, G.; Mirutse, G.; Gebretsadik, G.; Gebremedhin, G.; Weldearegay, H.; Berhe, K.; et al. Knowledge, perceptions, satisfaction, and readiness of health-care providers regarding COVID-19 in Northern Ethiopia. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 2021, 14, 1349–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, H.; Ma, S.; Jia, N.; Tian, J. Understanding public transport satisfaction in post COVID-19 pandemic. Transp. Policy 2021, 101, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, M.J.; Portillo, M.A.; Cuerdo-Vilches, T.; Oteiza, I.; Navas-Martín, M.Á. Habitability, resilience, and satisfaction in Mexican homes to COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 6993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gori, A.; Topino, E.; Di Fabio, A. The protective role of life satisfaction, coping strategies and defense mechanisms on perceived stress due to COVID-19 emergency: A chained mediation model. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e242402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasetyo, Y.T.; Tanto, H.; Mariyanto, M.; Hanjaya, C.; Young, M.N.; Persada, S.F.; Miraja, B.A.; Redi, A.A.N.P. Factors affecting customer satisfaction and loyalty in online food delivery service during the COVID-19 pandemic: Its relation with open innovation. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2021, 7, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almusharraf, N.; Khahro, S. Students satisfaction with online learning experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Emerg. Technol. Learn. 2020, 15, 246–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Y.; Cai, G.; Mo, Z.; Gao, W.; Xu, L.; Jiang, Y.; Jiang, J. The impact of COVID-19 on tourist satisfaction with B&B in Zhejiang, China: An importance–performance analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3747. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, D.L.; Gillaspy, J.A.; Purc-Stephenson, R. Reporting practices in confirmatory factor analysis: An overview and some recommendations. Psychol. Methods 2009, 14, 6–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, M.W.; Du Toit, S.H.C. Automated fitting of nonstandard models. Multivar. Behav. Res. 2010, 27, 269–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doll, W.J.; Xia, W.; Torkzadeh, G. A confirmatory factor analysis of the end-user computing satisfaction instrument. MIS Q. 1994, 18, 453–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentler, P. On the fit of models to covariances and methodology to the Bulletin. Psychol. Bull. 1992, 112, 400–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iacobucci, D. Structural equations modeling: Fit Indices, sample size, and advanced topics. J. Consum. Psychol. 2010, 20, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rong, T. AMOS and Research Methods; Chongqing University Press: Chongqing, China, 2009. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

| Latent Variable | Observed Variable |

|---|---|

| Perceived quality (PQ) | (PQ1). I understand how COVID-19 spreads |

| (PQ2). I understand the infectiousness of COVID-19 | |

| (PQ3). I can identify which type of mask is suitable for preventing COVID-19 | |

| (PQ4). I understand the number of infected people and the distribution of the hardest-hit areas | |

| (PQ5). I can correctly identify numerous rumors about the pandemic | |

| (PQ6). I understand the pandemic prevention policies | |

| Policy expectation (PE) | (PE1). My expectation of the response speed of relevant departments |

| (PE2). My expectation of the effectiveness of the pandemic response policies | |

| (PE3). My expectation of the feasibility of the pandemic response policies | |

| (PE4). My expectation of the action capacity of the relevant departments | |

| (PE5). My expectation of the professionalism of the pandemic response policies | |

| Pandemic prevention service satisfaction (SS) | (SS1). My satisfaction with the action capacity of the pandemic response policies |

| (SS2). My satisfaction with the effectiveness of the pandemic response policies | |

| (SS3). My satisfaction with the feasibility of the pandemic response policies | |

| (SS4). My satisfaction with the professionalism of the pandemic response policies | |

| (SS5). My satisfaction with the acquisition of the pandemic prevention materials | |

| (SS6). My overall satisfaction | |

| Resident complaints (RC) | (RC1). I believe there is a tendency to complain about pandemic prevention services |

| (RC2). I complain about pandemic prevention services to acquaintances | |

| (RC3). I complain about pandemic prevention services on social media | |

| (RC4). I express dissatisfaction with pandemic prevention services to relevant departments | |

| (RC5). An acquaintance has complained to me about pandemic prevention services | |

| Resident trust (RT) | (RT1). I tend to praise the government’s pandemic prevention work. |

| (RT2). I praised the pandemic prevention services to my friends. | |

| (RT3). I praise the pandemic prevention services on social media and the Internet | |

| (RT4). I trust the pandemic prevention information provided by the governments | |

| (RT5). I believe that the risk of infectious diseases will become higher and higher in the future | |

| (RT6). I will continue to support the work of relevant departments in the future | |

| Disaster situation (DS) | (DS1). The extent to which my daily life has been affected by the pandemic |

| (DS2). The extent to which my work has been affected by the pandemic | |

| (DS3). The extent to which my social interaction has been affected by the pandemic | |

| (DS4). The extent to which my health has been affected by the pandemic | |

| (DS5). The extent to which my psychological state has been affected by the pandemic | |

| (DS6). The extent to which my family and friends have been affected by the pandemic |

| Characteristic | Range | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 281 | 54.46 |

| Female | 235 | 45.54 | |

| Age | ≤17 | 61 | 11.82 |

| 18–30 | 149 | 28.88 | |

| 31–45 | 173 | 33.53 | |

| 46–60 | 82 | 15.89 | |

| ≥61 | 51 | 9.88 | |

| Education | Primary school and below | 31 | 6.01 |

| Junior high school | 59 | 11.43 | |

| High school, secondary school, and vocational high school | 124 | 24.03 | |

| Junior college | 175 | 33.92 | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 97 | 18.80 | |

| Master’s degree and above | 30 | 5.81 | |

| Monthly income (RMB) | <3000 | 136 | 26.36 |

| 3000–5999 | 206 | 39.92 | |

| 6000–9999 | 115 | 22.29 | |

| ≥10,000 | 57 | 11.04 | |

| None | 2 | 0.39 |

| Latent Variable | Observed Variable | Standard Load | CITC | T | p | CR | AVE | Cronbach’s α |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PE | PE1 | 0.719 | 0.654 | 0.852 | 0.535 | 0.851 | ||

| PE2 | 0.725 | 0.653 | 14.954 | *** | ||||

| PE3 | 0.704 | 0.644 | 14.548 | *** | ||||

| PE4 | 0.741 | 0.673 | 15.269 | *** | ||||

| PE5 | 0.766 | 0.688 | 15.708 | *** | ||||

| PQ | PQ1 | 0.778 | 0.719 | 0.885 | 0.562 | 0.885 | ||

| PQ2 | 0.742 | 0.696 | 17.181 | *** | ||||

| PQ3 | 0.751 | 0.692 | 17.415 | *** | ||||

| PQ4 | 0.745 | 0.695 | 17.268 | *** | ||||

| PQ5 | 0.741 | 0.69 | 17.173 | *** | ||||

| PQ6 | 0.739 | 0.689 | 17.113 | *** | ||||

| RC | RC1 | 0.728 | 0.668 | 0.872 | 0.578 | 0.872 | ||

| RC2 | 0.821 | 0.751 | 17.364 | *** | ||||

| RC3 | 0.748 | 0.69 | 15.944 | *** | ||||

| RC4 | 0.734 | 0.677 | 15.66 | *** | ||||

| RC5 | 0.766 | 0.706 | 16.313 | *** | ||||

| RT | RT1 | 0.765 | 0.717 | 0.895 | 0.588 | 0.895 | ||

| RT2 | 0.783 | 0.727 | 18.149 | *** | ||||

| RT3 | 0.751 | 0.706 | 17.314 | *** | ||||

| RT4 | 0.772 | 0.723 | 17.845 | *** | ||||

| RT5 | 0.757 | 0.713 | 17.456 | *** | ||||

| RT6 | 0.771 | 0.722 | 17.838 | *** | ||||

| SS | SS1 | 0.722 | 0.675 | 0.881 | 0.552 | 0.881 | ||

| SS2 | 0.769 | 0.711 | 16.392 | *** | ||||

| SS3 | 0.726 | 0.673 | 15.493 | *** | ||||

| SS4 | 0.756 | 0.703 | 16.128 | *** | ||||

| SS5 | 0.738 | 0.678 | 15.763 | *** | ||||

| SS6 | 0.745 | 0.694 | 15.895 | *** | ||||

| DS | DS1 | 0.766 | 0.72 | 0.9 | 0.6 | 0.899 | ||

| DS2 | 0.770 | 0.723 | 17.876 | *** | ||||

| DS3 | 0.760 | 0.712 | 17.617 | *** | ||||

| DS4 | 0.764 | 0.724 | 17.726 | *** | ||||

| DS5 | 0.796 | 0.741 | 18.559 | *** | ||||

| DS6 | 0.788 | 0.74 | 18.351 | *** |

| Path Relation | Standardized Estimate | Standard Error | T Statistics | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disaster situation → Policy expectation (H1) | 0.427 | 0.041 | 8.301 | *** |

| Disaster situation → Pandemic prevention service satisfaction (H2) | −0.206 | 0.039 | −3.834 | *** |

| Policy expectation → Pandemic prevention service satisfaction (H3) | −0.193 | 0.048 | −3.57 | *** |

| Perceived quality → Pandemic prevention service satisfaction (H4) | 0.246 | 0.043 | 5.029 | *** |

| Pandemic prevention service satisfaction → Resident complaints (H5) | −0.213 | 0.069 | −4.191 | *** |

| Pandemic prevention service satisfaction → Resident trust (H6) | 0.325 | 0.063 | 6.379 | *** |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, W.; Shi, Y.; Fan, L.; Huang, L.; Gao, J. Influencing Factors of Public Satisfaction with COVID-19 Prevention Services Based on Structural Equation Modeling (SEM): A Study of Nanjing, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 13281. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182413281

Chen W, Shi Y, Fan L, Huang L, Gao J. Influencing Factors of Public Satisfaction with COVID-19 Prevention Services Based on Structural Equation Modeling (SEM): A Study of Nanjing, China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(24):13281. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182413281

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Wei, Yijun Shi, Liwen Fan, Lijun Huang, and Jingyi Gao. 2021. "Influencing Factors of Public Satisfaction with COVID-19 Prevention Services Based on Structural Equation Modeling (SEM): A Study of Nanjing, China" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 24: 13281. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182413281

APA StyleChen, W., Shi, Y., Fan, L., Huang, L., & Gao, J. (2021). Influencing Factors of Public Satisfaction with COVID-19 Prevention Services Based on Structural Equation Modeling (SEM): A Study of Nanjing, China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(24), 13281. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182413281