The Impact of ERASMUS Exchanges on the Professional and Personal Development of Medical Students

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

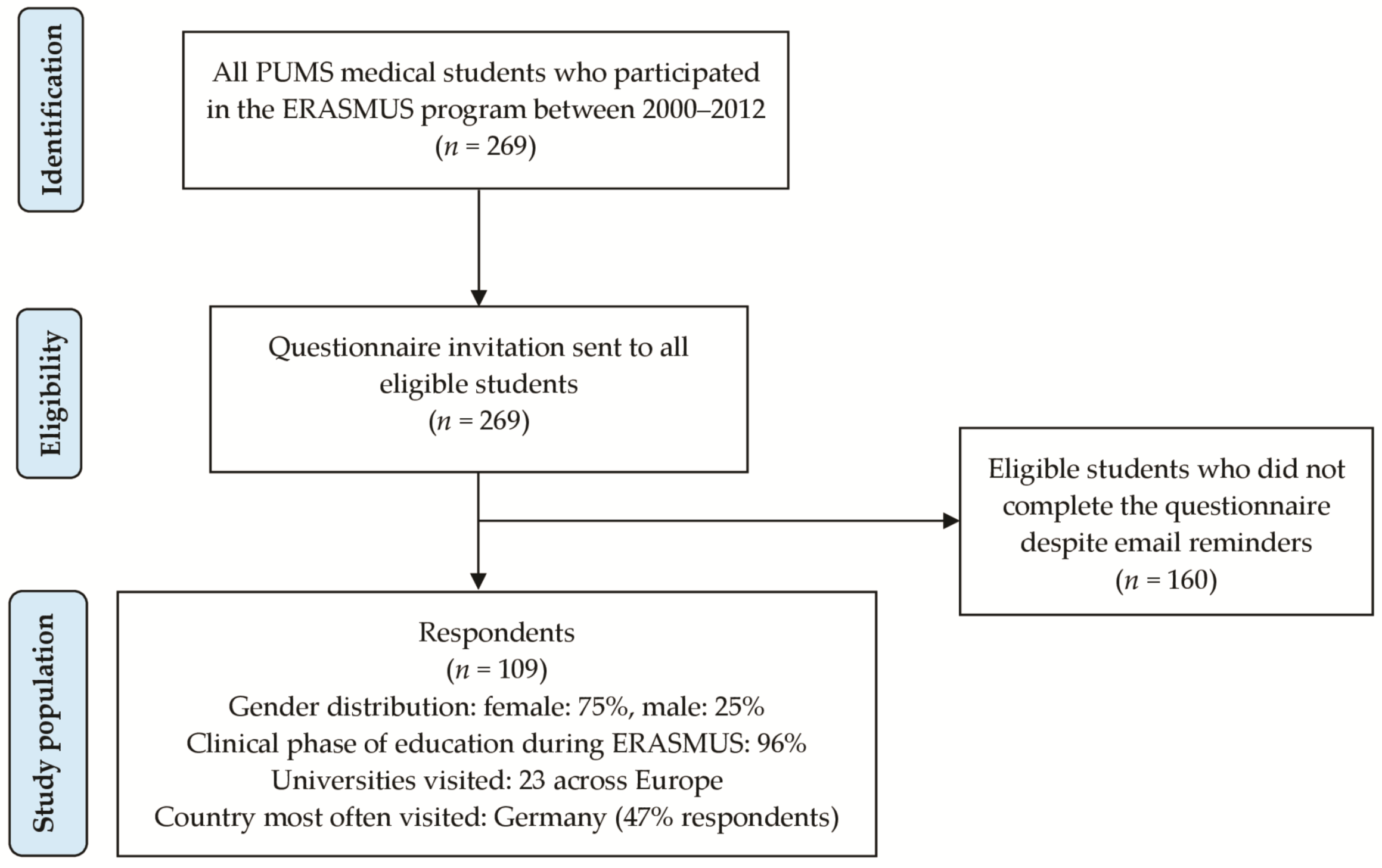

3.1. Study Population

3.2. Motivation

3.3. Language Experience and Impact

“Doctors often did not feel like speaking English, they spoke Dutch knowing that I could not understand it at all. It was also mandatory for me to participate in the meetings held in Dutch, which I could not understand. The classes lasted a very long time and often were not very educational. I had to stand in the operating room and not interrupt anybody. (...)” (P003)

“During my neurology classes […] the tutors generally did not care that they have ERASMUS students in the group and did not even bother to ask whether something needs to be repeated or translated into English (certainly a negative experience).” (P023)

3.4. Learning Experience and Impact

“We need:

“Possibility to choose any specialization regardless of the LEP [state exam] grade, better earnings during specialization. Possibility to change specialization. (…)” (P061)

“I definitely changed my approach to learning. This exchange opened my eyes. My studying has become more focused, effective, less rote learning, more understanding, and correlation. Paying attention to the really important stuff, not some test nuances.” (P059)

“Yes. I learned how to ‘learn’. Instead of memorizing drug doses by heart, I am now trying to remember where they are used. Learning doses will finally occur naturally. The same goes for the symptoms of diseases, diagnostic approach, and differentiation.” (P080)

“Studying has become a little more regular, a little more focused on practice. I paid a little less attention to the Polish school demands if I reckoned they were not right (...).” (P108)

“I learned an education system in which it is up to you what you get out of it and not that you are doing something because you are constantly controlled and tested.” (P057)

“[changing approach to learning] was difficult, because of the requirements of the home institution are different (emphasis on theory) (…).” (P037)

3.5. Healthcare and Clinical Practice Experience and Impact

“Yes, especially the approach to patients [has changed]. I was taught to respect the patient very, very much, always introduce myself and address them with impeccable manner, regardless of the situation.” (P063)

“During my clinical courses in the hospital, sometimes patients were homeless. Watching the doctors who treated them with great respect equal to other patients, I have definitely learned that every patient is equal, and everyone must be helped as best as we can regardless of the social or material status.” (P029)

3.6. Career and Professional Migration Experience and Impact

3.7. Personal and Social Experience and Impact

“I think that the most important benefits of participation in such a program are absolutely immeasurable and impossible to describe in any survey because they are mainly related to the evolution of consciousness, character, and horizons. I believe every student should have the opportunity to participate in this or any other form of exchange.” (P034)

3.8. ERASMUS as a Catalyst of Change?

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Questions Asked | No. of Respondents |

|---|---|

| 1. What is your age? (open question) | 99 |

| 2. What is your gender? (closed question) | 104 |

| 3. What academic year did you participate in the ERASMUS exchange? (closed question) | 109 |

| 4. Which university did you visit as part of the ERASMUS program? (closed question) | 106 |

| 5. Which year of study were you in when you undertook your ERASMUS exchange? (closed question) | 109 |

| 6. What area of medicine do you qualify, train in, or plan to do so? (closed question, more than one choice possible, including not intending to specialize). | 106 |

| 7. Which of the following best describe your current professional role (more than one possible)? (closed question) | 108 |

| 8. Since graduating, have you worked abroad in healthcare or university/research (if the answer is no, please go to question No. 11)? (Y/N closed question) | 107 |

| 9. Please tell us more about your work abroad in healthcare or university/research (please select boxes that apply). - Temporary post (healthcare) - Permanent post (healthcare) - Training post (specialty training) - Locum - Teaching post - Research - Other (closed question) | 28 |

| 10. Please tell us more about this post, e.g., when it began and will end, and what you hope to do afterward? (open question) | 24 |

| 11. Why did you take part in the ERASMUS exchange? - to experience this unique opportunity to study abroad - out of curiosity - to improve the quality of my education - to improve language skills - to experience a different culture - for a change of routine - to get to know a different educational system - to improve my social life - to improve my prospects of further study abroad - to improve my prospects of getting a job abroad - to improve my prospects of further study in Poland - to improve my prospects of getting a job in Poland - for personal reasons - for research opportunities - to undertake the specific courses offered - other (closed question, more than one choice possible) | 109 |

| 12. What do you feel were your major achievements during the ERASMUS visit? (open question) | 62 |

| 13. How would you rate the importance of the benefits you gained from your ERASMUS visit? - social - touristic - language - educational - professional networking - organization skills other (Likert 1–5 closed question, 1 = no benefit; 5 = great benefit) | 108 |

| 14. How would you rate the importance of the social benefits you gained from your ERASMUS visit? - Learning teamwork - Making international contacts - Keeping international contacts (after ERASMUS) - Learning to live independently - Making new friends - Rich and interesting social life - Other (...) (Likert 1–5 closed question, 1 = no benefit; 5 = great benefit) | 109 |

| 15. When choosing where to go, did language influence your choice? (Y/N closed question) | 109 |

| 16. If yes, did you want to visit a place where you would need to speak: - a language you have been learning - a language completely new for you (closed question) | 100 |

| 17. Did you speak your host country’s mother tongue? (Y/N closed question) | 109 |

| 18. Which language did you use to speak with fellow students and staff? - their mother tongue - another language when possible (closed question) | 108 |

| 19. How competent were you in communicating with fellow students and university staff? - fluent - little difficulty - moderate difficulty - severe difficulty (closed question) | 109 |

| 20. Which language did you use to speak with patients [MCQ] - their mother tongue - another language when possible - always with the aid of an interpreter - I did not have contact with patients (closed question) | 109 |

| 21. How competent were you in communicating with patients? - fluent - little difficulty - moderate difficulty - severe difficulty (closed question) | 108 |

| 22. How did your professional foreign language skills change as a result of your ERASMUS experience? - significantly improved - little improved - not affected - became worse (closed question) | 109 |

| 23. Did you note anything particularly different about the medical education system in the country you visited? If so, please describe. (open question) | 76 |

| 24. Do you recall any particularly memorable educational events (good or bad) during your ERASMUS exchange? If so, please describe briefly below, indicating whether each was positive or negative for you? (open question) | 61 |

| 25. How would you rate the competences of the host institution’s students’ when compared with that of Polish students from the home institution? - theoretical knowledge - practical skills (Likert 1–5 closed question, 1 = much worse; 5 = much better) | 102 |

| 26. Following on from your ERASMUS educational experiences, have you changed your approach to learning? (open question) | 74 |

| 27. Following on from your ERASMUS educational experiences, are there changes you would like to see introduced to the Polish medical education system or methods? (open question) | 79 |

| 28. Did your ERASMUS visit influence your career plans? (Y/N closed question) | 104 |

| 29. If yes, please tell us whether, as a result of ERASMUS, you were less or more likely: - to undertake postgraduate studying and training abroad? - to look for a permanent job abroad? (Likert 1–5 closed question) | 76 |

| 30. Did you note anything particularly different about the healthcare system in the country you visited? (open question) | 65 |

| 31. Following on from your ERASMUS healthcare experiences, have you changed your approach to clinical practice? (open question) | 67 |

| 32. Following on from your ERASMUS healthcare experiences, are there changes you would like to see introduced to the Polish healthcare system? (open question) | 67 |

| 33. Have you tried to implement changes to the Polish educational or healthcare systems or convince others to do so as a result of your ERASMUS experience? (Y/N closed question) | 104 |

| 34. If so, what was the outcome of your efforts to implement change? (open question) | 19 |

| 35. Do you have any further comments about your ERASMUS experiences or the effect the visit has had on you? (open question) | 39 |

References

- Patrício, M.; Harden, R.M. The Bologna Process—A global vision for the future of medical education. Med. Teach. 2010, 32, 305–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erasmus+ EU Programme for Education, Training, Youth and Sport. Available online: https://erasmus-plus.ec.europa.eu (accessed on 31 October 2021).

- Findlay, A.; King, R.; Geddes, A.; Smith, F.; Stam, M.; Dunne, M.; Skeldon, R.; Ahrens, J. Motivations and Experiences of UK Students Studying Abroad; Department for Business Innovation and Skills: Dundee, Scotland, UK, 2010.

- Rodríguez González, C.; Bustillo Mesanza, R.; Mariel, P. The determinants of international student mobility flows: An empirical study on the Erasmus programme. High. Educ. 2011, 62, 413–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teichler, U. Temporary Study Abroad: The Life of ERASMUS Students. Eur. J. Educ. 2004, 39, 395–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keogh, J.; Russel-Roberts, E. Exchange programmes and student mobility: Meeting student’s expectations or an expensive holiday? Nurse Educ. Today 2009, 29, 108–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishigori, H.; Takahashi, O.; Sugimoto, N.; Kitamura, K.; McMahon, G.T. A national survey of international electives for medical students in Japan: 2009–2010. Med. Teach. 2012, 34, 71–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeffrey, J.; Dumont, R.A.; Kim, G.Y.; Kuo, T. Effects of international health electives on medical student learning and career choice: Results of a systematic literature review. Fam. Med. 2011, 43, 21–28. [Google Scholar]

- Bryła, P. The Impact of International Student Mobility on Subsequent Employment and Professional Career: A Large-scale Survey among Polish Former Erasmus Students. Procedia—Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 176, 633–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Onwuegbuzie, A.J.; Leech, N.L. On Becoming a Pragmatic Researcher: The Importance of Combining Quantitative and Qualitative Research Methodologies. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 375–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, L.; Manion, L.; Morrison, K. Research Methods in Education, 7th ed.; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2011; p. xxii. 758p. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, M.J.; Huntington, M.K.; Hunt, D.D.; Pinsky, L.E.; Brodie, J.J. Educational effects of international health electives on U.S. and Canadian medical students and residents: A literature review. Acad. Med. J. Assoc. Am. Med. Coll. 2003, 78, 342–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abedini, N.C.; Gruppen, L.D.; Kolars, J.C.; Kumagai, A.K. Understanding the effects of short-term international service-learning trips on medical students. Acad. Med. J. Assoc. Am. Med. Coll. 2012, 87, 820–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Böttcher, L.; Araújo, N.A.; Nagler, J.; Mendes, J.F.; Helbing, D.; Herrmann, H.J. Gender Gap in the ERASMUS Mobility Program. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0149514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NIL. Zestawienie Liczbowe Lekarzy i Lekarzy Dentystów Wg Wieku, Płci i Tytułu Zawodowego. Available online: https://nil.org.pl/uploaded_files/1633418981_za-wrzesien-zestawienie-nr-03.pdf (accessed on 31 October 2021).

- Kumwenda, B.; Royan, D.; Ringsell, P.; Dowell, J. Western medical students’ experiences on clinical electives in sub-Saharan Africa. Med. Educ. 2014, 48, 593–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lesjak, M.; Juvan, E.; Ineson, E.M.; Yap, M.H.T.; Axelsson, E.P. Erasmus student motivation: Why and where to go? High. Educ. 2015, 70, 845–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, M.; Boateng, E.A.; Evans, C. Should I stay or should I go? A systematic review of factors that influence healthcare students’ decisions around study abroad programmes. Nurse Educ. Today 2016, 39, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otero, M.S. The Socio-Economic Background of Erasmus Students: A Trend Towards Wider Inclusion? Int. Rev. Educ. 2008, 54, 135–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Goodman, B.; Jones, R.; Sanchón Macias, M. An exploratory survey of Spanish and English nursing students’ views on studying or working abroad. Nurse Educ. Today 2008, 28, 378–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waters, J.; Brooks, R.; Pimlott-Wilson, H. Youthful escapes? British students, overseas education and the pursuit of happiness. Soc. Cult. Geogr. 2011, 12, 455–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Marshall, J.E. Experiences of student midwives learning and working abroad in Europe: The value of an Erasmus undergraduate midwifery education programme. Midwifery 2017, 44, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Williams, G.C.; Saizow, R.B.; Ryan, R.M. The importance of self-determination theory for medical education. Acad. Med. J. Assoc. Am. Med. Coll. 1999, 74, 992–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ten Cate, T.J.; Kusurkar, R.A.; Williams, G.C. How self-determination theory can assist our understanding of the teaching and learning processes in medical education. AMEE guide No. 59. Med. Teach. 2011, 33, 961–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnett, K. System members at odds: Managing divergent perspectives in the higher education change process. J. High. Educ. Policy Manag. 2011, 33, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crow, S.M.; Hartman, S.J. A case study of organizational decline: Lessons for health care organizations. Health Care Manag. 2003, 22, 256–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kautsch, M. Migracje personelu medycznego i jej skutki dla funkcjonowania systemu ochrony zdrowia w Polsce. Zdrowie Publiczne i Zarządzanie 2013, 11, 169–179. [Google Scholar]

- Kolanowska, E. 10 lat Erasmusa w Polsce 1998–2008; Fundacja Rozwoju Systemu Edukacji: Warsaw, Poland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Bracht, O.; Engel, C.; Janson, K.; Over, A.; Schomburg, H.; Teichler, U. The Professional Value of ERASMUS Mobility; Final Report; The European Commission—DG Education and Culture: Kassel, Hessen, Germany, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Bennhold, K. Quietly Sprouting: A European Identity. New York Times. 26 April 2005. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2005/04/26/world/europe/quietly-sprouting-a-european-identity.html (accessed on 31 October 2021).

| Category | Reason | % (n = 109) |

|---|---|---|

| Language | to improve language skills | 85 |

| Educational | to explore a different educational system | 69 |

| to improve the quality of my education | 61 | |

| to improve my prospects of further study abroad | 35 | |

| to undertake the specific courses offered | 22 | |

| for research opportunities | 7 | |

| to improve my prospects of further study in Poland | 7 | |

| Personal | to use the existing opportunity | 88 |

| out of curiosity | 55 | |

| to improve my prospects of getting a job abroad | 44 | |

| for a change of routine | 40 | |

| to improve my prospects of getting a job in Poland | 17 | |

| for personal reasons | 15 | |

| Social | experience a different culture | 72 |

| to lead a more interesting social life | 41 |

| Axial Code | Theme | Exemplary Quote |

|---|---|---|

| Professionalism | Doctors’ and students’ professional conduct towards patients | “Doctors’ and medical students’ approach to patients was very professional and showed impeccable manners.” (P036) |

| Culture of teaching and learning | Student-teacher partnership | “Students are partners for lecturers, not ‘pupils’.” (P084) |

| Students have responsibility | “In the University I was on ERASMUS much attention is paid to students’ self-study” (P005) “Students in the clinical part of the training have much more responsibilities than the Polish intern” (P046) | |

| Approaches to the curriculum | Emphasis on the clinical, practical and important | “(…) German students, even though they study less extensively, have much better knowledge of the essentials. They learn practical and important things.” (P005) “All students can draw blood, put in intravenous lines, change dressings, which is a rare thing among students in Poland” (P076) |

| Individual teaching | “Students usually follow the doctor one by one and take over some of the doctors’ duties, therefore, helping them.” (P005) | |

| Flexibility | “Less rigorous attendance check. Student takes responsibility for their education and should be conscious of its purpose and importance” (P094) | |

| Case-based learning | “More emphasis on practice: seminars in the form of Case-based Learning” (P023) | |

| Practice of evidence-based medicine | “Preparing to work in the principles of evidence-based medicine: searching articles on certain clinical topics and discussing them in a presentation with grading the level of evidence” (P009) | |

| Assessment reflecting the practical and important knowledge and skills | “Exams rely upon solving clinical cases, which, in my opinion, better prepares for future practice.” (P041) | |

| Modern facilities | E-learning platform | “[university name] has an e-learning platform. Departments make educational and exam-relevant content available online (...) For example, Department of Orthopaedics and Neurology posted educational videos from physical examination, X-rays, MRI, CT interpretations, etc.” (P029) |

| Good medical textbooks specifically designed for medical students | “Students have good textbooks–something like our state-exam preparatory textbooks, which explain plain and short the most important material” (P040) | |

| Internship | The final year of medical school similar to the internship in Poland | “Final 6th year of studies similar to Polish internship” (P069) |

| Axial Code | Themes | Exemplary Quote |

|---|---|---|

| Learning style | Emphasis on the clinical, practical, and important | “Certainly, I understood that you need to learn important things that one will remember in the future and not everything a medical textbook for a given specialty contains.” (P057) |

| Learning focused on attaining higher levels in Bloom’s taxonomy | “I try not to focus on the details. I learn so that I can put the acquired knowledge into practice.” (P076) | |

| Less stressful attitude to learning and assessment in Poland | “Yes, the grades are not as important to me as they were before the exchange.” (P050) | |

| Practice of evidence-based medicine | “Yes. I started to learn more algorithms and based on current reports (articles) than textbooks.” (P063) | |

| Learning from foreign textbooks | “Yes, I focused on the essentials and started learning from German and English textbooks.” (P052) | |

| Self-directed learning | “I learned distance to exams. I began to learn more for myself and pay more attention to long term retention of what I learned.” (P069) | |

| Emphasis on professionalism | “It was difficult because the requirements of the home institution are different (emphasis on theory), but [the ERASMUS] definitely changed my approach to the patient, nowadays I pay more attention to it.” (P037) | |

| Developing research interest | “The Erasmus program allowed me to further develop and work abroad. It is very easy to start a doctoral thesis, both research and retrospective.” (P002) | |

| Personal | Balancing studying with spare time activities | “Studying for four years in Poznan, I sacrificed most of my time studying. (…) Most people have no interests/hobbies outside of medicine. Their full attention and time are focused on exams. Here [in the host institution], it looks completely different. (…) Many people have their passions, which they constantly develop. Certainly, after the ERASMUS, I will try to change the way of learning. I would try to develop my interests, better organize my time off and balance it with studying, just as I managed to do here.” (P029) |

| Broadening horizons | “Maybe not towards learning, but I expanded my worldview more and changed my approach to the patient” (P018) | |

| Unchanged approach | Change impeded by the Polish medical education system and its predominant culture | “Of course, I regret that after returning to Poland I will have to study again as befits a Polish medical student and I will certainly have less time for non-scientific activities” (P079) |

| Unchanged: always strived to learn the best one can | “Rather not, I try to learn the best I can.” (P044) |

| Axial Code | Theme | Exemplary Quote |

|---|---|---|

| Modern healthcare | Patient-centered and friendly healthcare | “Yes, more attention is paid to the doctor-patient relationship.” (P037) |

| Hospitals well equipped and comfortable | “Hospitals are better equipped, more diagnostic tests are available without waiting in the queue” (P053) | |

| GPs have a central role in the system | “A GP has more power, and greater skills. In Poland, a GP’s work often comes down to the extension of chronic prescriptions and referrals to specialists.” (P037) | |

| Well-developed outpatient care | “A more extensive outpatient clinic system. A system focused on the effectiveness of its activities, less willing to admit patients to the ward. A very fashionable system of one-day admissions, performing minor procedures in outpatient conditions, e.g., tonsillectomy.” (P080) | |

| Professionalism and culture | Doctor-patient partnership | “(...) In Germany, I noticed a much smaller distance between a doctor and a patient-they are on almost equal terms. In Poland we’ve seen many doctors who behave as if they were “gods”. On the other hand, I also noticed much more mutual respect. Perhaps due to the fact that we do not respect patients they do not respect us?” (P072) |

| Training | Junior doctors have independence and access to good clinical training | “Junior doctors even in large clinical hospitals are from the onset of their career allowed to do many medical procedures or operate and have large independence in their work. In Poland, a junior doctor frequently does not have such independence.” (P059) |

| Finance and insurance | Significantly more financial resources in the system | “The French healthcare system, being financed much better than the Polish one, offers patients much more high-quality services. Modern drugs, diagnostic procedures, relatively short waiting times-are common.” (P108) |

| Coexistence of state or private insurance | “In Germany, in addition to the state insurance, there is a widely available private insurance system. Almost every hospital has dedicated parts of wards for private patients. Queues are much shorter there or even none. (…) In Poland, on the other hand, everything for everyone” (P072) | |

| The liability of health insurance clearly defined | “In Poland, it is not defined what is covered by the national insurance. Refusals of financing certain treatments by hospitals are always met with astonishment [among patients]. In Germany, the financing is different. There are well-defined limits of coverage (liability), and if someone has more expectations, they can always change their insurance. (…) The rules are clearly defined.” (P018) | |

| Rational allocation of resources | “Reasonable taking care of finances: if in a given case two therapy options can be used with similar effectiveness-the cheaper one is chosen-thanks to this when the patient really requires expensive treatment-there is no waiting with its implementation to check if the “standard therapy” will not work. (…)” (P034) | |

| Information flow | Comprehensive electronic patient health records | “From the first day of class, I admired the complete integrated system of patient data. All procedures, diagnostic tests, consultations, hospital stays, outpatient visits are stored in one computer system, accessible to all doctors after logging in.” (P005) |

| Thorough patient information on the disease, therapy, and plans | “I like the detailed patient information on the procedures they are subjected to. Each patient receives a well-prepared printed detailed description of the procedure and possible side effects. This facilitates cooperation with the patient.” (P005) | |

| Consultations with the doctors the patient attended before | “In addition, in hospitals, doctors frequently consult on the phone with a doctor under whose care the patient was before. This avoids double testing and accelerates the acquisition of information about the patient.” (P005) | |

| Management | Better organized and managed healthcare | “Doctors work in better conditions, they have more time to deal with patients, salaries are higher and therefore they do not need to work several jobs or split time between the hospital and their private practice.” (P053) |

| More time for patient consultations | “In Sweden, a doctor has 30 min for a patient in an outpatient clinic and not 7–10 min like in Poland.” (P037) | |

| Active involvement of nurses and social workers in patient care | “The presence of social workers in hospitals who take over a certain part of the duties of doctors (which in Poland have to be performed by doctors alone or are not performed by anyone)” (P013) |

| Axial Code | Theme | No. (n = 19) |

|---|---|---|

| No or insignificant change | Little or no effect | 13 |

| Conversations about differences with colleagues | 2 | |

| Ceased to convince other doctors | 1 | |

| Frustration | 1 | |

| Reasons for lack of success in change | Most doctors accept the traditional system | 1 |

| Opposition to changes in the profession | 1 | |

| Difficulty changing system that lasts for years | 1 | |

| Successful change | Limited to my own approach to education/teaching | 4 |

| Limited to my own approach to healthcare delivery | 3 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Żebryk, P.; Przymuszała, P.; Nowak, J.K.; Cerbin-Koczorowska, M.; Marciniak, R.; Cameron, H. The Impact of ERASMUS Exchanges on the Professional and Personal Development of Medical Students. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 13312. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182413312

Żebryk P, Przymuszała P, Nowak JK, Cerbin-Koczorowska M, Marciniak R, Cameron H. The Impact of ERASMUS Exchanges on the Professional and Personal Development of Medical Students. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(24):13312. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182413312

Chicago/Turabian StyleŻebryk, Paweł, Piotr Przymuszała, Jan Krzysztof Nowak, Magdalena Cerbin-Koczorowska, Ryszard Marciniak, and Helen Cameron. 2021. "The Impact of ERASMUS Exchanges on the Professional and Personal Development of Medical Students" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 24: 13312. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182413312

APA StyleŻebryk, P., Przymuszała, P., Nowak, J. K., Cerbin-Koczorowska, M., Marciniak, R., & Cameron, H. (2021). The Impact of ERASMUS Exchanges on the Professional and Personal Development of Medical Students. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(24), 13312. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182413312