Socioeconomic Status, Health and Lifestyle Settings as Psychosocial Risk Factors for Road Crashes in Young People: Assessing the Colombian Case

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedure and Data Analysis

2.3. Index Construction

- For what concerns SES: Socio-economic stratification, which in Colombia is a way to classify the residential properties that must receive public services and subsidies according to their social stratum, are established in the Law 142 from 1994 [63].SEP indicators include the wage reported in the Minimum Legal Wages for the year 2020 in Colombia, the occupational status and the educational level.Evaluation of wealth assets: residing in one’s own house (belonging to the individual or to the nucleus of co-habitation, where no rent is to be paid); access to a computer; money for leisure; savings; debts; permanent access to the internet; and covered month (which means the feeling of being able to manage with the available monthly income).Number of people who inhabit the home. The average number for Colombian homes is 3.3 in urban zones and 3.9 in rural zones. Furthermore, 52.7% of homes with 5 or more people reported incomes below 2 minimum wages [64]. This type of family structure, or cultures that foster familistic societies, can be not so good on an economic level. This is due to the fact that, regardless of the possible social support that these networks provide, economic resources seem to be more associated with living alone instead [65].

- Regarding health: the perception of having a good health, the use of medicines and the body mass index (BMI) were evaluated. In addition, some of the main causes of death and non-communicable diseases were considered as well: cancer, diabetes, hypertension/high blood pressure, dyslipidemia (evaluated through the vector: HDL-LDL cholesterol, triglycerides) and cardiovascular diseases. Additionally, diagnosis of a mental/psychological disorder, general self-reported stress and fatigue were taken into account.

- For lifestyle: having a sedentary life; doing sports at least 3 times a week; doing sports at least 30 min every time; smoking; drinking alcohol; self-assessment of one’s eating habits; walking; and using a bike were considered.Sleeping hours per day (24 h). Regularly sleeping less than 7 h per night can lead to adverse health conditions, such as weight gain and obesity, hypertension, depression, diabetes, heart disease and stroke, and increased risk of death; between 7 and 9 h could be considered a normal range for young adults and adults, while more than 9 h could be enough for young adults and for people recovering from sleep debt or suffering from illnesses. Nevertheless, it is still unknown whether sleeping more than 9 h per night could imply health risks [66].

- RTCs in a dichotomous way No/Yes (0–1): have you ever suffered a traffic crash? Suffering a crash as a road actor, a variable that was considered when the participant was matched in the vector: having a traffic crash, or a crash as a passenger, on a bike, as a pedestrian or as a driver. The variables that compose this vector were also used to study the contrasts.

- RTCs as continuous variable: number of traffic crashes throughout one’s life; number of crashes suffered as a passenger in one’s life; number of crashes suffered on a bike; number of crashes suffered as a pedestrian; number of crashes suffered as a driver during one’s life.

2.4. Compliance with Ethical Standards

3. Results

3.1. PCA Indices Construction

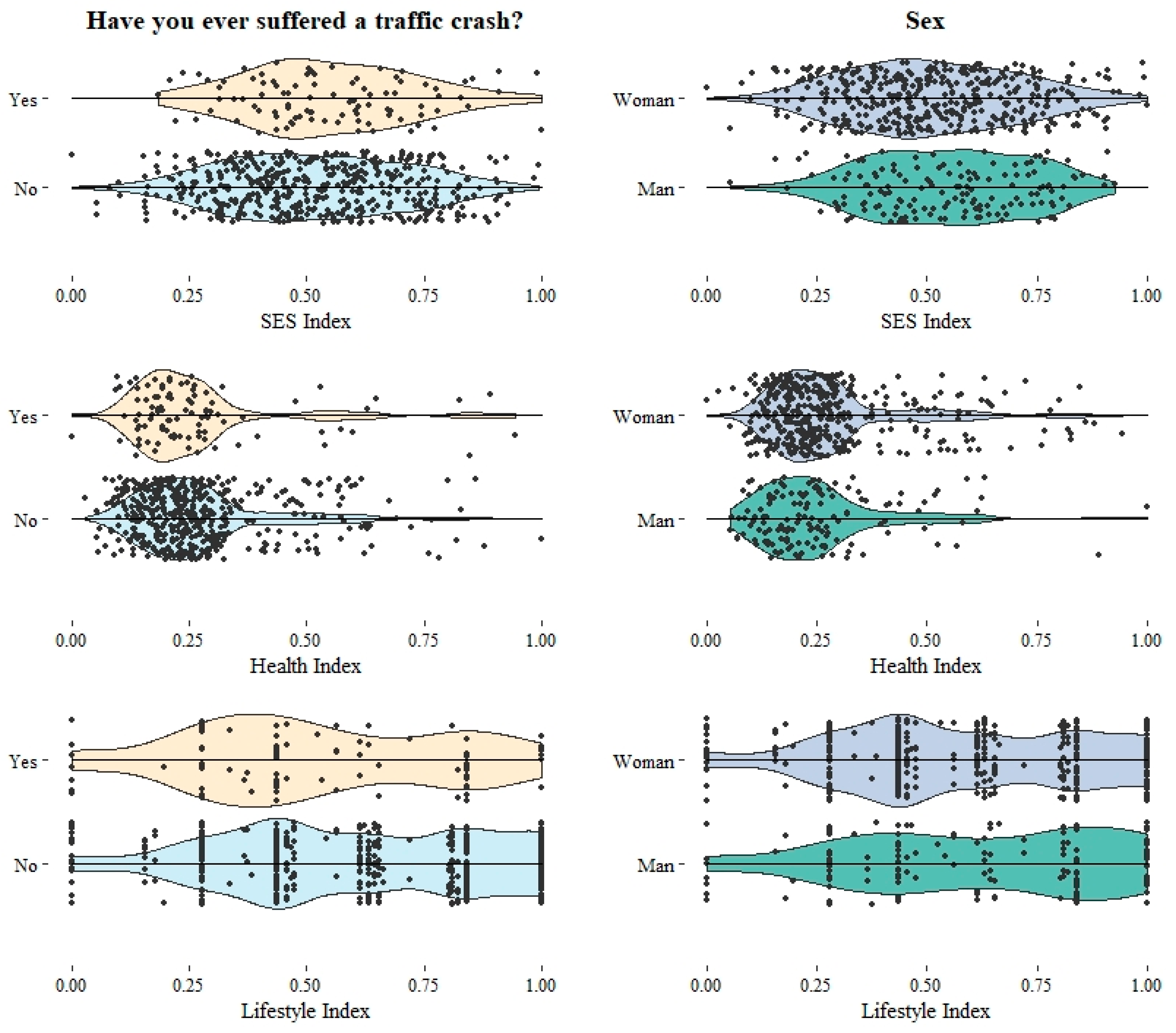

3.2. Means and Frequency Contrast

4. Discussion

4.1. Mobility and RTCs Patterns of Young Colombians

4.2. Social and Health Determinants in Young Colombians’ RTCs

4.2.1. Socioeconomic status (SES) and Young Colombians

4.2.2. Health, Lifestyle and Young Colombians

5. Conclusions

Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Instruction | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Current working situation | Unemployed student | Employed | Retired | * Unemployed or studying as their only occupation, employed, and retired | |||||

| Highest educational level achieved/currently attending | Cannot read or write | No studies | Primary school | High school | Technical training | Graduate | Postgraduate | PhD | |

| <high school | >high school | ||||||||

| Low | Intermediate | High | High-high | * Low: lower than high school; intermediate: high school or technical training; high: university/graduate; High-high: postgraduate and/or PhD | |||||

| Socioeconomic Status | Status 1 low-low | Status 2 low | Status 3 middle-low | Status 4 middle | Status 5 high | Status 6 high-high | In Colombia it is a way to classify the residential properties that must receive public services and subsidies as established in the Ley 142 de 1994 | ||

| <Status 4 | =>Status 4 | ||||||||

| Low-low (status 1 or less) | Low (status 2) | Middle (status 3) | High (status 4–6) | * As other studies in Colombia have done [89,90]. | |||||

| Approximate monthly income(Pesos $ COP) | Continuous COP | * In Colombian Pesos (COP). | |||||||

| Continuous SMLMV | Current minimum legal monthly income (SMLMV) 2020. | ||||||||

| <=1.37 SMLMV | >1.37 SMLMV | The middle class receives between 600,000 and 3,000,000 for the year 2020. Those below 1,200,000 are assumed to be vulnerable, and those who are above are middle class or higher. This value divided by the SMLMV equals 1.37. | |||||||

| Less than 1 SMLMV | Between 1 and 2 SMLMV | More than 2 SMLMV | The DANE, in its graphic reports, usually uses this categorization. | ||||||

| How many people do you live with? | Continuous | People someone lives with, without including oneself. | |||||||

| >=4 people | <4 people | The average number of people inhabiting Colombian homes is 3.3 in urban zones and 3.3 in rural zones [49]. | |||||||

| Continuous | Calculation of the number of individuals that live in the home, including the participant. One-person homes tend to have a higher income and more financial stability. | ||||||||

| >=6 people | 4–5 people | 2–3 people | One-person | ||||||

| Lives in one’s own house EBC1 | No | Yes | * Belonging to the individual or to the nucleus of co-habitation, where no rent is to be paid. | ||||||

| Owns a car EBC2 | No | Yes | Belonging to the individual or to the nucleus of co-habitation. | ||||||

| Cellphone EBC3 | No | Yes | |||||||

| Personal computer EBC4 | No | Yes | * | ||||||

| Money for leisure EBC5 | No | Yes | * | ||||||

| Paid vacation EBC6 | No | Yes | |||||||

| Savings EBC7 | No | Yes | |||||||

| Debts EBC8 | No | Yes | * Reverse variable | ||||||

| Access to the Internet EBC9 | No | Yes | * | ||||||

| Covered month EBC10 | No | Yes | * Which means the feeling of being able to manage with the available monthly income. | ||||||

| Tablet, iPad EBC11 | No | Yes | |||||||

| Monthly income EBC12 | No | Yes | |||||||

| EBC Belongings scale | Continuous | All characteristics are added up through variable addition approach [88], following the absence-presence EBC pattern. | |||||||

| <4 | >4 | All EBC characteristics are added, and a cutting edge is placed in the middle | |||||||

| Low-low | low | Intermediate | High | All EBC characteristics are added and classified in terciles | |||||

| Instruction | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Is my health good? | No | Yes | * Reverse variable | ||

| Body Mass Index | Continuous | * Weight/height (m)2 | |||

| Normal or low < 24.94 | Overweight => 24.96 & < 30 | Obesity => 30 | |||

| low <= 18.42 | Normal > 18.42 & <= 24.94 | Overweight >24.94 & < 30 | Obesity >= 30 | ||

| Diagnosed as overweight or with obesity? | No | Yes | |||

| Diagnosed with cancer? | No | Yes | |||

| Diagnosed with coronary (ischemic) disease? | No | Yes | |||

| Diagnosed with cerebrovascular disease? | No | Yes | |||

| Diagnosed with diabetes? | No | Yes | |||

| Diagnosed with arterial hypertension? | No | Yes | Used to build the hypertension vector: hypertension and high pressure. | ||

| Not matched | Matched | * The participant was matched in the vector: hypertension and high pressure | |||

| Have you ever been diagnosed with high blood pressure? | No | Yes | Doesn’t know | ||

| No | Yes | People choosing the “doesn’t know” option are assumed as missing data. Used to build the hypertension vector: hypertension and high pressure. | |||

| Have you been diagnosed with dyslipidemia? | No | Yes | |||

| Not matched | Matched | * The participant was matched in the vector: HDL-LDL cholesterol, triglycerides | |||

| Have you ever been diagnosed with high cholesterol? | No | Yes | Doesn’t know | ||

| No | Yes | People choosing the “doesn’t know” option are assumed as missing data. Used to build the dyslipidemia vector: HDL-LDL cholesterol, triglycerides. | |||

| Have you ever been diagnosed with high triglycerides? | No | Yes | Doesn’t know | ||

| No | Yes | People choosing the “doesn’t know” option are assumed as missing data. Used to build the dyslipidemia vector: HDL-LDL cholesterol, triglycerides. | |||

| Have you ever been diagnosed with low HDL Cholesterol (good cholesterol)? | No | Yes | Doesn’t know | ||

| No | Yes | People choosing the “doesn’t know” option are assumed as missing data. Used to build the dyslipidemia vector: HDL-LDL cholesterol, triglycerides. | |||

| Have you ever been diagnosed with high LDL Cholesterol (bad cholesterol)? | No | Yes | Doesn’t know | ||

| No | Yes | People choosing the “doesn’t know” option are assumed as missing data. Used to build the dyslipidemia vector: HDL-LDL cholesterol, triglycerides. | |||

| Have you ever been diagnosed with low blood pressure? | No | Yes | Doesn’t know | ||

| No | Yes | People choosing the “doesn’t know” option are assumed as missing data. | |||

| Have you ever been diagnosed with cardiovascular disease? | No | Yes | |||

| Have you ever been diagnosed with a mental/psychological disorder? | No | Yes | * | ||

| On a scale from 0 to 10, how stressed are you feeling? | Continuous | * Likert scale assumed as continuous 0 not stressed at all-10 very stressed | |||

| Not stressed at all | Average stress | Very stressed | Likert 0–10 categorized in terciles. | ||

| In general, how tired/fatigued do you feel? | Continuous | * Likert scale assumed as continuous 0 not fatigued at all-10 very fatigued | |||

| Not fatigued at all | Average fatigue | Very fatigued | Likert 0–10 categorized in terciles. |

| Instruction | 0 | 1 | 2 | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Do you have a sedentary life? | No | Yes | * Reverse variable | |

| Do you exercise 3 times per week? | No | Yes | * | |

| Do you exercise at least 30 min every time? | No | Yes | * | |

| Do you take any medicines? | No | Yes | Reverse variable | |

| Do you smoke? | No | Yes | Former smoker | Former smoker: used to smoke, but not anymore. |

| No or former smoker | Yes | * Reverse variable | ||

| Do you drink alcohol? | No | Yes | Former drinker | Former drinker: used to drink, but not anymore. |

| No or former drinker | Yes | * Reverse variable | ||

| Do you use any drugs? | Not matched | Matched | The participant was matched in the vector: marihuana, cocaine, other drugs | |

| How many hours do you sleep? | Continuous | Calculation of the total number of hours slept (day and night) | ||

| <7 | >9 | 7–9 h | Sleeping less than 7 h per night can lead to adverse health conditions; between 7 and 9 h could be considered a normal range for young adults, while more than 9 h could be enough for young adults and for people recovering from sleep debt or suffering from illnesses [66]. | |

| On a scale from 0 to 10, how good is your diet? | Continuous | Likert scale assumed as continuous 0 bad diet-10 good diet | ||

| Bad | Average | Good | Likert 0–10 categorized in terciles. | |

| Do you walk in your city? | No | Yes | ||

| Do you use a bike in your city? | No | Yes |

References

- Gopalakrishnan, S. A public health perspective of road traffic accidents. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2012, 1, 144–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shrivastava, S.R.; Shrivastava, P.S.; Ramasamy, J. Scope of public health measures in ensuring road safety. J. Inj. Violence Res. 2014, 6, 95–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. Global Status Report on Road Safety 2018; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Hyder, A.A.; Paichadze, N.; Toroyan, T.; Peden, M.M. Monitoring the Decade of Action for Global Road Safety 2011–2020: An update. Glob. Public Health 2017, 12, 1492–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, T.; Wang, Y.; Xu, T.; Li, L.; Huo, M.; Li, X.; He, Y.; Lin, Q.; Mei, B.; Zhou, X.; et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 3327 cases of traffic trauma deaths in Beijing from 2008 to 2017: A retrospective analysis. Medicine 2020, 99, e18567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Kuhn, M.; Prettner, K.; Bloom, D.E. The global macroeconomic burden of road injuries: Estimates and projections for 166 countries. Lancet Planet. Health 2019, 3, e390–e398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sargazi, A.; Sargazi, A.; Nadakkavukaran Jim, P.K.; Danesh, H.; Aval, F.; Kiani, Z.; Lashkarinia, A.; Sepehri, Z. Economic Burden of Road Traffic Accidents; Report from a Single Center from South Eastern Iran. Bull. Emerg. Trauma 2016, 4, 43–47. [Google Scholar]

- Montoro, L.; Alonso, F.; Esteban, C.; Toledo, F. Manual de Seguridad Vial: El Factor Humano, 1st ed.; Barcelona-España: Ariel, Israel, 2000; p. 384. [Google Scholar]

- Jafarpour, S.; Rahimi-Movaghar, V. Determinants of risky driving behavior: A narrative review. Med. J. Islamic Repub. Iran 2014, 28, 142. [Google Scholar]

- Touahmia, M. Identification of Risk Factors Influencing Road Traffic Accidents. Eng. Technol. Appl. Sci. Res. 2018, 8, 2417–2421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petridou, E.; Moustaki, M. Human factors in the causation of road traffic crashes. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2000, 16, 819–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mairean, C.; Havarneanu, C.E. The relationship between drivers’ illusion of superiority, aggressive driving, and self-reported risky driving behaviors. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2018, 55, 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavacuiti, C.; Ala-Leppilampi, K.J.; Mann, R.E.; Govoni, R.; Stoduto, G.; Smart, R.; Locke, J.A. Victims of Road Rage: A Qualitative Study of the Experiences of Motorists and Vulnerable Road Users. Violence Vict. 2013, 28, 1068–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alonso, F.; Esteban, C.; Montoro, L.; Serge, A. Conceptualization of aggressive driving behaviors through a Perception of aggressive driving scale (PAD). Transp. Res. Part F Psychol. Behav. 2019, 60, 415–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elgar, F.J.; Pförtner, T.-K.; Moor, I.; De Clercq, B.; Stevens, G.W.J.M.; Currie, C. Socioeconomic inequalities in adolescent health 2002–2010: A time-series analysis of 34 countries participating in the Health Behaviour in School-aged Children study. Lancet 2015, 385, 2088–2095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Braveman, P.A.; Cubbin, C.; Egerter, S.; Chideya, S.; Marchi, K.S.; Metzler, M.; Posner, S. Socioeconomic Status in Health ResearchOne Size Does Not Fit All. JAMA 2005, 294, 2879–2888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flaskerud, J.H.; DeLilly, C.R. Social determinants of health status. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2012, 33, 494–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.M. Social Determinants of Health and Related Inequalities: Confusion and Implications. Front. Public Health 2019, 7, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shafiei, S.; Yazdani, S.; Jadidfard, M.-P.; Zafarmand, A.H. Measurement components of socioeconomic status in health-related studies in Iran. BMC Res. Notes 2019, 12, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallo, L.C.; de Los Monteros, K.E.; Shivpuri, S. Socioeconomic Status and Health: What is the role of Reserve Capacity? Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2009, 18, 269–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Van den Berghe, W. The Association between Road Safety and Socioeconomic Situation (SES); An International Literature Review; Vias Institute—Knowledge Centre Road Safety: Brussels, Belgium, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Sehat, M.; Naieni, K.H.; Asadi-Lari, M.; Foroushani, A.R.; Malek-Afzali, H. Socioeconomic Status and Incidence of Traffic Accidents in Metropolitan Tehran: A Population-based Study. Int. J. Prev. Med. 2012, 3, 181–190. [Google Scholar]

- Atombo, C.; Wu, C.; Tettehfio, E.O.; Agbo, A.A. Personality, socioeconomic status, attitude, intention and risky driving behavior. Cogent Psychol. 2017, 4, 1376424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngueutsa, R.; Kouabenan, D.R. Accident history, risk perception and traffic safe behaviour. Ergonomics 2017, 60, 1273–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, T.G.; Ouimet, M.C.; Eldeb, M.; Tremblay, J.; Vingilis, E.; Nadeau, L.; Pruessner, J.; Bechara, A. The effect of age on the personality and cognitive characteristics of three distinct risky driving offender groups. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2017, 113, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Robert, S.A.; Cherepanov, D.; Palta, M.; Dunham, N.C.; Feeny, D.; Fryback, D.G. Socioeconomic status and age variations in health-related quality of life: Results from the national health measurement study. J. Gerontol. Ser. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2009, 64, 378–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Straatmann, V.S.; Lai, E.; Lange, T.; Campbell, M.C.; Wickham, S.; Andersen, A.-M.N.; Strandberg-Larsen, K.; Taylor-Robinson, D. How do early-life factors explain social inequalities in adolescent mental health? Findings from the UK Millennium Cohort Study. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2019, 73, 1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Noh, J.-W.; Jo, M.; Huh, T.; Cheon, J.; Kwon, Y.D. Gender differences and socioeconomic status in relation to overweight among older Korean people. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e97990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Galobardes, B.; Shaw, M.; Lawlor, D.A.; Lynch, J.W.; Smith, G.D. Indicators of socioeconomic position (part 1). J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2006, 60, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Saydah, S.H.; Imperatore, G.; Beckles, G.L. Socioeconomic status and mortality: Contribution of health care access and psychological distress among U.S. adults with diagnosed diabetes. Diabetes Care 2013, 36, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Back, J.H.; Lee, Y. Gender differences in the association between socioeconomic status (SES) and depressive symptoms in older adults. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2011, 52, e140–e144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacquet, E.; Robert, S.; Chauvin, P.; Menvielle, G.; Melchior, M.; Ibanez, G. Social inequalities in health and mental health in France. The results of a 2010 population-based survey in Paris Metropolitan Area. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0203676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marmot, M.G.; Kogevinas, M.; Elston, M.A. Social/economic status and disease. Annu. Rev. Public Health 1987, 8, 111–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler, N.E.; Ostrove, J.M. Socioeconomic status and health: What we know and what we don’t. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1999, 896, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winkleby, M.A.; Jatulis, D.E.; Frank, E.; Fortmann, S.P. Socioeconomic status and health: How education, income, and occupation contribute to risk factors for cardiovascular disease. Am. J. Public Health 1992, 82, 816–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Khalatbari-Soltani, S.; Cumming, R.G.; Delpierre, C.; Kelly-Irving, M. Importance of collecting data on socioeconomic determinants from the early stage of the COVID-19 outbreak onwards. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujishiro, K.; Xu, J.; Gong, F. What does “occupation” represent as an indicator of socioeconomic status?: Exploring occupational prestige and health. Soc. Sci. Med. 2010, 71, 2100–2107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polinder, S.; Haagsma, J.; Bos, N.; Panneman, M.; Wolt, K.K.; Brugmans, M.; Weijermars, W.; van Beeck, E. Burden of road traffic injuries: Disability-adjusted life years in relation to hospitalization and the maximum abbreviated injury scale. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2015, 80, 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, A.H.; Dorn, L. Stress, fatigue, health, and risk of road traffic accidents among professional drivers: The contribution of physical inactivity. Annu Rev. Public Health 2006, 27, 371–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ding, D.; Gebel, K.; Phongsavan, P.; Bauman, A.E.; Merom, D. Driving: A road to unhealthy lifestyles and poor health outcomes. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e94602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdoli, N.; Farnia, V.; Delavar, A.; Esmaeili, A.; Dortaj, F.; Farrokhi, N.; Karami, M.; Shakeri, J.; Holsboer-Trachsler, E.; Brand, S. Poor mental health status and aggression are associated with poor driving behavior among male traffic offenders. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2015, 11, 2071–2078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhu, S.; Layde, P.M.; Guse, C.E.; Laud, P.W.; Pintar, F.; Nirula, R.; Hargarten, S. Obesity and risk for death due to motor vehicle crashes. Am. J. Public Health 2006, 96, 734–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homaie Rad, E.; Khodadady-Hasankiadeh, N.; Kouchakinejad-Eramsadati, L.; Javadi, F.; Haghdoost, Z.; Hosseinpour, M.; Tavakoli, M.; Davoudi-Kiakalayeh, A.; Mohtasham-Amiri, Z.; Yousefzadeh-Chabok, S. The relationship between weight indices and injuries and mortalities caused by the motor vehicle accidents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Inj. Violence Res. 2020, 12, 85–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Geng, L. Effects of Socioeconomic Status on Physical and Psychological Health: Lifestyle as a Mediator. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Williams, J.L.; Rheingold, A.A.; Knowlton, A.W.; Saunders, B.E.; Kilpatrick, D.G. Associations between motor vehicle crashes and mental health problems: Data from the National Survey of Adolescents-Replication. J. Trauma. Stress 2015, 28, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Shadloo, B.; Motevalian, A.; Rahimi-Movaghar, V.; Amin-Esmaeili, M.; Sharifi, V.; Hajebi, A.; Radgoodarzi, R.; Hefazi, M.; Rahimi-Movaghar, A. Psychiatric Disorders Are Associated with an Increased Risk of Injuries: Data from the Iranian Mental Health Survey (IranMHS). Iran. J. Public Health 2016, 45, 623–635. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Alarcón, J.D.; Saladich, I.G.; Cuellar, L.V.; Gallardo, A.M.R.; Arce, C.M.; Cosp, X.B. Mortality caused by traffic accidents in colombia. comparison with other countries. Safety 2020, 2011, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Oviedo-Trespalacios, O.; Scott-Parker, B. The sex disparity in risky driving: A survey of Colombian young drivers. Traffic Inj. Prev. 2018, 19, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- DANE. Censo Nacional de Población y Vivienda 2018. Available online: https://sitios.dane.gov.co/cnpv/#!/ (accessed on 15 March 2020).

- Brysbaert, M. How Many Participants Do We Have to Include in Properly Powered Experiments? A Tutorial of Power Analysis with Reference Tables. J. Cogn. 2019, 2, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trafimow, D.; Myüz, H.A. The sampling precision of research in five major areas of psychology. Behav. Res. Methods 2019, 51, 2039–2058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Riley, R.D.; Snell, K.I.; Ensor, J.; Burke, D.L.; Harrell, F.E., Jr.; Moons, K.G.; Collins, G.S. Minimum sample size for developing a multivariable prediction model: PART II—binary and time-to-event outcomes. Stat. Med. 2019, 38, 1276–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kadam, P.; Bhalerao, S. Sample size calculation. Int. J. Ayurveda Res. 2010, 1, 55–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Piovesana, A.; Senior, G. How small is big: Sample size and skewness. Assessment 2018, 25, 793–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Congreso República Colombia. Ley Estatutaria 1885 de 2018 por la Cual se Modifica la Ley 1622 de 2013 y se Dictan Otras Disposiciones; Colombia, C.d.l.R.d., Ed.; Corte Constitucional de Colombia: Bogotá, Colombia, 2018; p. 20. [Google Scholar]

- DANE. Panorama Sociodemográfico de la Juventud en Colombia ¿Quiénes son, Qué Hacen y Cómo se Sienten en el Contexto Actual? Available online: https://www.dane.gov.co/files/investigaciones/genero/informes/informe-panorama-sociodemografico-juventud-en-colombia.pdf (accessed on 29 September 2020).

- Van Selm, M.; Jankowski, N.W. Conducting online surveys. Qual. Quant. 2006, 40, 435–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regmi, P.R.; Waithaka, E.; Paudyal, A.; Simkhada, P.; Van Teijlingen, E. Guide to the design and application of online questionnaire surveys. Nepal J. Epidemiol. 2016, 6, 640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jafari, M.; Ansari-Pour, N. Why, When and How to Adjust Your P Values? Cell J. 2019, 20, 604–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Available online: https://www.yumpu.com/en/document/read/6853895/r-a-language-and-environment-for-statistical-computing (accessed on 29 September 2020).

- Chao, Y.-S.; Wu, C.-J. Principal component-based weighted indices and a framework to evaluate indices: Results from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey 1996 to 2011. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0183997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howe, L.D.; Hargreaves, J.R.; Huttly, S.R.A. Issues in the construction of wealth indices for the measurement of socio-economic position in low-income countries. Emerg. Themes Epidemiol. 2008, 5, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Congreso República Colombia. Ley 142 de 1994. In Diario Oficial 41.433; Colombia, C.d.l.R.d., Ed.; Corte Constitucional de Colombia: Bogotá, Colombia, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- DANE. Encuesta Nacional de Presupuestos de los Hogares (ENPH) 2016–2017. Boletín Técnico. Departamento Administrativo Nacional de Estadística (DANE). Available online: https://www.dane.gov.co/files/investigaciones/boletines/enph/boletin-enph-2017.pdf (accessed on 3 July 2020).

- Mudrazija, S.; Angel, J.L.; Cipin, I.; Smolic, S. Living Alone in the United States and Europe: The Impact of Public Support on the Independence of Older Adults. Res. Aging 2020, 42, 150–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, N.F.; Badr, M.S.; Belenky, G.; Bliwise, D.L.; Buxton, O.M.; Buysse, D.; Dinges, D.F.; Gangwisch, J.; Grandner, M.A.; Kushida, C.; et al. Recommended Amount of Sleep for a Healthy Adult: A Joint Consensus Statement of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine and Sleep Research Society. Sleep 2015, 38, 843–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, A.F.; Shabanova, V.I. Responsibility of drivers, by age and gender, for motor-vehicle crash deaths. J. Saf. Res. 2003, 34, 527–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- COLPSIC, C.C.d.P. Deontología y Bioética del Ejercicio de la Psicología en Colombia; Editorial El Manual Moderno Colombia: Bogotá, Colombia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Amerson, R.M.; Strang, C.W. Addressing the Challenges of Conducting Research in Developing Countries. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. Off. Publ. Sigma Theta Tau Int. Honor Soc. Nurs. 2015, 47, 584–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lonczak, H.S.; Neighbors, C.; Donovan, D.M. Predicting risky and angry driving as a function of gender. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2007, 39, 536–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özkan, T.; Lajunen, T. What causes the differences in driving between young men and women? The effects of gender roles and sex on young drivers’ driving behaviour and self-assessment of skills. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2006, 9, 269–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roshanfekr, P.; Khodaie-Ardakani, M.-R.; Malek Afzali Ardakani, H.; Sajjadi, H. Prevalence and Socio-Economic Determinants of Disabilities Caused by Road Traffic Accidents in Iran; A National Survey. Bull. Emerg. Trauma 2019, 7, 60–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landale, N.S.; Oropesa, R.S.; Bradatan, C. Hispanic families in the United States: Family Structure and Process in an Era of Family Change. In Hispanics and the Future of America; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2006; Volume 5. [Google Scholar]

- Hurtado, D.; Kawachi, I.; Sudarsky, J. Social capital and self-rated health in Colombia: The good, the bad and the ugly. Soc. Sci. Med. 2011, 72, 584–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woodcock, J.; Aldred, R. Cars, corporations, and commodities: Consequences for the social determinants of health. Emerg. Themes Epidemiol. 2008, 5, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kim, J.-K.; Ulfarsson, G.F.; Shankar, V.N.; Kim, S. Age and pedestrian injury severity in motor-vehicle crashes: A heteroskedastic logit analysis. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2008, 40, 1695–1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villaveces, A.; Nieto, L.A.; Ortega, D.; Rios, J.F.; Medina, J.J.; Gutierrez, M.I.; Rodriguez, D. Pedestrians’ perceptions of walkability and safety in relation to the built environment in Cali, Colombia, 2009–2010. Inj. Prev. J. Int. Soc. Child Adolesc. Inj. Prev. 2012, 18, 291–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Greening, L.; Stoppelbein, L. Young drivers’ health attitudes and intentions to drink and drive. J. Adolesc. Health 2000, 27, 94–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, R. Cycling and health. Doctors should cycle and recommend it to their patients. BMJ (Clin. Res. Ed.) 2000, 321, 386. [Google Scholar]

- Shariat, A.; Ansari, N.N.; Cleland, J.A.; Hakakzadeh, A.; Kordi, R.; Kargarfard, M. Therapeutic Effects of Cycling on Disability, Mobility, and Quality of Life in Patients Post Stroke. Iran. J. Public Health 2019, 48, 355–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leyland, L.-A.; Spencer, B.; Beale, N.; Jones, T.; van Reekum, C.M. The effect of cycling on cognitive function and well-being in older adults. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0211779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackay, A.; Mackay, D.F.; Celis-Morales, C.A.; Lyall, D.M.; Gray, S.R.; Sattar, N.; Gill, J.M.R.; Pell, J.P.; Anderson, J.J. The association between driving time and unhealthy lifestyles: A cross-sectional, general population study of 386 493 UK Biobank participants. J. Public Health 2019, 41, 527–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brandt, C.J.; Clemensen, J.; Nielsen, J.B.; Søndergaard, J. Drivers for successful long-term lifestyle change, the role of e-health: A qualitative interview study. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e017466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mechakra-Tahiri, S.D.; Freeman, E.E.; Haddad, S.; Samson, E.; Zunzunegui, M.V. The gender gap in mobility: A global cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2012, 12, 598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Arora, S.K.; Shah, D.; Chaturvedi, S.; Gupta, P. Defining and Measuring Vulnerability in Young People. Indian J. Community Med. Off. Publ. Indian Assoc. Prev. Soc. Med. 2015, 40, 193–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, H.; Reynolds, C.F.R.; Cuijpers, P. Protecting youth mental health, protecting our future. World Psychiatry 2017, 16, 327–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ross, L.A.; Schmidt, E.L.; Ball, K. Interventions to maintain mobility: What works? Accid. Anal. Prev. 2013, 61, 167–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Reckien, D. What is in an index? Construction method, data metric, and weighting scheme determine the outcome of composite social vulnerability indices in New York City. Reg. Environ. Chang. 2018, 18, 1439–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Buitrago-Lopez, A.; Van den Hooven, E.H.; Rueda-Clausen, C.F.; Serrano, N.; Ruiz, A.J.; Pereira, M.A.; Mueller, N.T. Socioeconomic status is positively associated with measures of adiposity and insulin resistance, but inversely associated with dyslipidaemia in Colombian children. J. Epidemiol Community Health 2015, 69, 580–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villamor, E.; Mora-Plazas, M.; Forero, Y.; Lopez-Arana, S.; Baylin, A. Vitamin B-12 status is associated with socioeconomic level and adherence to an animal food dietary pattern in Colombian school children. J. Nutr. 2008, 138, 1391–1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Variable Mean (SD) | Fr | Sex | Income SMLMV | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Man % (n = 146) | Woman % (n = 413) | None (n = 160) | <1 (n = 263) | 1–2 (n = 111) | >2 (n = 27) | ||

| Age | χ2 = 11.645, p = 0.009, C = 0.143 | χ2 = 98.227, p < 0.001, C = 0.386 | |||||

| 20.83(2.49) | 21.4(2.6) | 20.63(2.43) | 19.99(2.13) | 20.58(2.09) | 22.23(2.76) | 22.63(3.64) | |

| 18 | 94 | 11 a | 18.9 b | 29.4 b | 12.9 a | 7.2 a | 18.5 |

| 19–21 | 284 | 47.3 | 51.8 | 48.8 | 60.5 b | 36.9 a | 22.2 a |

| 22–24 | 126 | 26 | 21.1 | 18.8 | 20.5 | 33.3 b | 18.5 |

| 25–28 | 57 | 15.8 b | 8.2 a | 3.1 a | 6.1 a | 22.5 b | 40.7 b |

| Educational level | χ2 = 22.572, p = 0.007, C = 0.197 | ||||||

| Primary school or lower | 2 | 0 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0 | 0.9 | 0 |

| High school or technical | 334 | 52.7 | 62 | 61.9 | 54 a | 73.9 b | 40.7 a |

| University | 220 | 46.6 | 36.6 | 36.9 | 45.2 b | 24.3 a | 55.6 |

| Postgraduate or PhD | 5 | 0.7 | 1 | 0.6 | 0.8 a | 0.9 | 3.7 |

| Socioeconomic stratification | χ2 = 32.525, p < 0.001, C = 0.235 | ||||||

| Status 1 low-low | 42 | 8.2 | 7.3 | 4.4 | 10.3 b | 6.4 | 3.7 |

| Status 2 low | 229 | 38.4 | 42.1 | 44.9 | 35.5 a | 55.5 b | 14.8 a |

| Status 3 middle | 225 | 39 | 40.8 | 40.5 | 41.2 | 34.5 | 55.6 |

| Status 4 or higher | 61 | 14.4 | 9.8 | 10.1 | 13 | 3.6 a | 25.9 b |

| Occupational situation | χ2 = 100.112, p < 0.001, C = 0.389 | ||||||

| Unemployed or studying only | 355 | 61 | 64.3 | 90.6 b | 61.8 | 35.1 a | 33.3 a |

| Employed | 205 | 39 | 35.7 | 9.4 a | 38.2 | 64.9 b | 66.7 b |

| Do you drive any type of motor vehicle? | χ2 = 10.327, p = 0.001, C = 0.135 | χ2 = 9.002, p = 0.029, C = 0.126 | |||||

| No | 492 | 80.1 a | 90.3 b | 90.6 | 88.2 | 86.5 | 70.4 a |

| Yes | 69 | 19.9 b | 9.7 a | 9.4 | 11.8 | 13.5 | 29.6 b |

| Do you walk in your city? | |||||||

| No | 35 | 7.5 | 5.8 | 8.8 | 5.7 | 3.6 | 7.4 |

| Yes | 526 | 92.5 | 94.2 | 91.2 | 94.3 | 96.4 | 92.6 |

| Do you use a bike in your city? | χ2 = 33.055, p < 0.001, C = 0.236 | ||||||

| No | 413 | 55.5 a | 79.9 b | 80.6 | 71.1 | 71.2 | 66.7 |

| Yes | 148 | 44.5 b | 20.1 a | 19.4 | 28.9 | 28.8 | 33.3 |

| General reported crashes | |||||||

| No | 464 | 77.4 | 84.7 | 88.1 | 80.2 | 81.1 | 81.5 |

| Yes | 97 | 22.6 | 15.3 | 11.9 | 19.8 | 18.9 | 18.5 |

| Crashes reported | χ2 = 14.654, p = 0.002, C = 0.160 | ||||||

| 0.29(0.79) | 0.49(1.15) | 0.22(0.58) | 0.18(0.55) | 0.32(0.82) | 0.36(0.95) | 0.37(0.84) | |

| None | 464 | 77.4 a | 84.7 b | 88.1 | 80.2 | 81.1 | 81.5 |

| 1 acc | 59 | 10.3 | 10.7 | 6.9 | 12.9 | 11.7 | 3.7 |

| 2 acc | 20 | 4.8 | 3.1 | 3.8 | 3.4 | 1.8 | 11.1 |

| 3 or more acc | 18 | 7.5 b | 1.5 a | 1.2 | 3.4 | 5.4 | 3.7 |

| Crashes as a road actor | χ2 = 18.492, p < 0.001, C = 0.179 | ||||||

| No | 340 | 45.9 a | 66.1 b | 68.1 | 57 | 61.3 | 48.1 |

| Yes | 221 | 54.1 b | 33.9 a | 31.9 | 43 | 38.7 | 51.9 |

| Variable | Comp.1 | Comp.2 | Comp.3 | Comp.4 | Comp.5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Socioeconomic status SES (n = 556) | |||||

| Occupational situation (does not work/student-works) | 0.32 | 0.53 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| Socioeconomic stratification (low-low, low, middle, high) | 0.31 | −0.27 | −0.14 | 0.34 | 0.59 |

| Educational level (low, intermediate, high, high-high) | 0.09 | −0.17 | 0.66 | 0.46 | −0.31 |

| Income (continuous in Colombian pesos) | 0.34 | 0.37 | −0.06 | 0.41 | −0.14 |

| Residing in one’s own house (No/Yes) | 0.14 | −0.17 | −0.7 | 0.33 | −0.45 |

| Having access to a computer (No/Yes) | 0.35 | −0.07 | 0.08 | −0.49 | −0.49 |

| Money for leisure (No/Yes) | 0.44 | −0.14 | 0.21 | 0.03 | 0.11 |

| Having debts (reversed No/Yes) | −0.15 | −0.57 | 0.02 | 0.06 | −0.13 |

| Access to the internet (No/Yes) | 0.38 | −0.16 | −0.08 | −0.39 | 0.25 |

| Covered month (No/Yes) | 0.42 | −0.26 | 0.01 | −0.04 | −0.08 |

| Eigenvalue | 1.88 | 1.63 | 1.08 | 1.03 | 0.85 |

| Proportion of variance | 18.87% | 16.29% | 10.78% | 10.30% | 8.52% |

| Cumulative variance | 18.87% | 35.16% | 45.95% | 56% | 64.78% |

| Health (n = 557) | |||||

| BMI (continuous in kg/mts2) | 0.04 | 0.55 | 0.15 | 0.58 | 0.57 |

| Hypertension (No/Yes matched in the vector: hypertension and high blood pressure) | −0.01 | 0.55 | 0.09 | −0.75 | 0.24 |

| Dyslipidemia (No/Yes matched in the vector: cholesterol, LDL, HDL, triglycerides) | −0.18 | 0.53 | 0.2 | 0.21 | −0.76 |

| Diagnosis of a mental/psychological disorder (No/Yes) | 0.27 | 0.32 | −0.65 | −0.11 | −0.12 |

| Perception of good health (No/Yes) | 0.41 | 0.04 | −0.51 | 0.21 | −0.05 |

| General stress (assumed as continuous 0–10) | 0.61 | 0.05 | 0.33 | −0.04 | −0.11 |

| General fatigue (assumed as continuous 0–10) | 0.6 | −0.09 | 0.37 | −0.05 | −0.07 |

| Eigenvalue | 1.81 | 1.23 | 1.07 | 0.93 | 0.85 |

| Proportion of variance | 25.92% | 17.59% | 15.33% | 13.31% | 12.16% |

| Cumulative variance | 25.92% | 43.51% | 58.84% | 72.15% | 84.31% |

| Lifestyle (n = 561) | |||||

| Having a sedentary life (reversed No/Yes) | 0.57 | 0.02 | 0.08 | 0.66 | 0.48 |

| Exercising 3 times per week (No/Yes) | 0.58 | 0.12 | 0.03 | 0.07 | −0.8 |

| Exercising for 30 min every time (No/Yes) | 0.56 | 0.09 | 0.02 | −0.74 | 0.36 |

| Smoking (reversed No-ex/Yes) | 0.14 | −0.67 | −0.72 | 0 | −0.03 |

| Drinking alcohol (reversed No-ex/Yes) | 0.05 | −0.72 | 0.68 | −0.07 | −0.05 |

| Eigenvalue | 2.19 | 1.2 | 0.78 | 0.47 | 0.36 |

| Proportion of variance | 43.88% | 24.06% | 15.54% | 93.60% | 71.60% |

| Cumulative variance | 43.88% | 67.95% | 83.49% | 92.84% | 100% |

| Variable Mean(SD) | Fr | SES Index 0.52(0.19) | Health Index 0.27(0.15) | Lifestyle Index 0.59(0.28) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low (n = 186) | Average (n = 183) | High (n = 187) | Good (n = 187) | Average (n = 186) | Poor (n = 184) | Unhealthy (n = 127) | Average (n = 269) | Healthy (n = 165) | ||

| Health Index | χ2 = 15.081, p = 0.005, C = 0.162 | |||||||||

| Good | 187 | 23.6 | 33.1 | 42.1 | 23.6 | 33.1 | 42.1 | 23.6 a | 33.1 | 42.1 b |

| Average | 186 | 33.1 | 33.5 | 33.5 | 33.1 | 33.5 | 33.5 | 33.1 | 33.5 | 33.5 |

| Poor | 184 | 43.3 | 33.5 | 24.4 | 43.3 | 33.5 | 24.4 | 43.3 b | 33.5 | 24.4 a |

| Drive any type of motor vehicle | χ2 = 7.569, p = 0.023, C = 0.116 | |||||||||

| No | 492 | 91.4 | 89.1 | 82.4 a | 87.2 | 88.7 | 87.5 | 88.2 | 88.5 | 86.1 |

| Yes | 69 | 8.6 | 10.9 | 17.6 b | 12.8 | 11.3 | 12.5 | 11.8 | 11.5 | 13.9 |

| Do you walk in your city? | ||||||||||

| No | 35 | 6.5 | 5.5 | 7 | 7 | 4.8 | 6.5 | 7.1 | 6.7 | 4.8 |

| Yes | 526 | 93.5 | 94.5 | 93 | 93 | 95.2 | 93.5 | 92.9 | 93.3 | 95.2 |

| Do you use a bike in your city? | χ2 = 18.778, p < 0.001, C = 0.180 | |||||||||

| No | 413 | 73.7 | 76.5 | 72.2 | 70.1 | 74.2 | 76.1 | 77.2 | 79.6 | 61.2 a |

| Yes | 148 | 26.3 | 23.5 | 27.8 | 29.9 | 25.8 | 23.9 | 22.8 | 20.4 | 38.8 b |

| Reported crashes | χ2 = 8.866, p = 0.012, C = 0.125 | |||||||||

| No | 464 | 87.1 | 79.2 | 81.3 | 80.2 | 83.3 | 84.8 | 74 a | 85.9 | 84.2 |

| Yes | 97 | 12.9 | 20.8 | 18.7 | 19.8 | 16.7 | 15.2 | 26 b | 14.1 | 15.8 |

| Crashes riding a bike | χ2 = 11.228, p = 0.004, C = 0.140 | |||||||||

| No | 487 | 87.6 | 89.6 | 82.9 | 84.5 | 85.5 | 90.2 | 89.8 | 90 a | 79.4 a |

| Yes | 74 | 12.4 | 10.4 | 17.1 | 15.5 | 14.5 | 9.8 | 10.2 | 10 b | 20.6 b |

| Crash as a pedestrian | χ2 = 10.322, p = 0.006, C = 0.169 | |||||||||

| No | 281 | 79.7 | 86.2 b | 68.2 a | 79.3 | 77.6 | 80.3 | 75.4 | 77 | 84.5 |

| Yes | 74 | 20.3 | 13.8 a | 31.8 b | 20.7 | 22.4 | 19.7 | 24.6 | 23 | 15.5 |

| Crash as a driver | χ2 = 11.804, p = 0.003, C = 0.382 | |||||||||

| No | 45 | 68.8 | 45 | 75.8 | 58.3 | 71.4 | 65.2 | 40 a | 58.1 | 91.3 b |

| Yes | 24 | 31.2 | 55 | 24.2 | 41.7 | 28.6 | 34.8 | 60 b | 41.9 | 8.7 a |

| Sex | χ2 = 6.567, p = 0.037, C = 0.108 | |||||||||

| Man | 146 | 22.6 | 26.5 | 29.9 | 31.6 | 25.8 | 21.4 | 27 | 21.6 a | 32.7 b |

| Woman | 413 | 77.4 | 73.5 | 70.1 | 68.4 | 74.2 | 78.6 | 73 | 78.4 b | 67.3 a |

| Age | ||||||||||

| 18 | 94 | 16.7 | 15.3 | 17.1 | 20.3 | 18.3 | 11.4 | 13.4 | 18.2 | 17 |

| 19–21 | 284 | 50 | 50.8 | 51.3 | 47.1 | 50 | 54.9 | 57.5 | 47.6 | 50.3 |

| 22–24 | 126 | 23.7 | 21.9 | 22.5 | 24.1 | 22.6 | 21.2 | 23.6 | 21.2 | 23.6 |

| 25–28 | 57 | 9.7 | 12 | 9.1 | 8.6 | 9.1 | 12.5 | 5.5 | 13 | 9.1 |

| Contrasting Variable | Continuous | Mean No/Man | Mean Yes/Woman | t.test | df | C.low | C.high | p | p.ad | EF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reported crashes (No = 464, Yes = 97) | Lifestyle Index | 0.60 | 0.52 | 2.69 | 139.83 | 0.02 | 0.14 | 0.008 | 0.027 | 0.08 |

| Age | 20.69 | 21.53 | −2.93 | 134.97 | −1.40 | −0.27 | <0.001 | 0.015 | −0.84 | |

| Crash as a road actor (No = 340, Yes = 221) | Age | 20.53 | 21.30 | −3.54 | 447.00 | −1.19 | −0.34 | <0.001 | <0.001 | −0.77 |

| Drive any type of motor vehicle (No = 492, Yes = 69) | Crash as a driver | 0.22 | 0.84 | −4.73 | 68.00 | −0.95 | −0.39 | <0.001 | <0.001 | −0.67 |

| Age | 20.67 | 21.99 | −3.73 | 82.99 | −2.01 | −0.61 | <0.001 | 0.002 | −1.31 | |

| Income in SMLMV | 0.08 | 0.23 | −2.94 | 75.71 | −0.26 | −0.05 | 0.004 | 0.017 | −0.15 | |

| SES Index | 0.51 | 0.58 | −2.39 | 83.23 | −0.12 | −0.01 | 0.019 | 0.049 | −0.06 | |

| Crash as a driver (No = 45, Yes = 24) | Lifestyle Index | 0.66 | 0.43 | 3.31 | 55.93 | 0.09 | 0.36 | 0.002 | 0.009 | 0.22 |

| Using a bike in the city (No = 413, Yes = 148) | Age | 20.58 | 21.54 | −3.92 | 242.39 | −1.44 | −0.48 | <0.001 | 0.001 | −0.96 |

| Lifestyle Index | 0.57 | 0.65 | −3.16 | 261.10 | −0.14 | −0.03 | 0.002 | 0.011 | −0.08 | |

| Sex (Man = 146, Woman = 413) | Crash riding a bike | 0.65 | 0.15 | 4.18 | 173.96 | 0.27 | 0.74 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.50 |

| Reported crashes | 2.18 | 1.41 | 2.79 | 171.50 | 0.08 | 0.47 | 0.006 | 0.038 | 0.28 | |

| Age | 21.40 | 20.63 | 3.11 | 240.01 | 0.28 | 1.25 | 0.002 | 0.019 | 0.77 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Serge, A.; Quiroz Montoya, J.; Alonso, F.; Montoro, L. Socioeconomic Status, Health and Lifestyle Settings as Psychosocial Risk Factors for Road Crashes in Young People: Assessing the Colombian Case. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 886. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18030886

Serge A, Quiroz Montoya J, Alonso F, Montoro L. Socioeconomic Status, Health and Lifestyle Settings as Psychosocial Risk Factors for Road Crashes in Young People: Assessing the Colombian Case. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(3):886. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18030886

Chicago/Turabian StyleSerge, Andrea, Johana Quiroz Montoya, Francisco Alonso, and Luis Montoro. 2021. "Socioeconomic Status, Health and Lifestyle Settings as Psychosocial Risk Factors for Road Crashes in Young People: Assessing the Colombian Case" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 3: 886. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18030886

APA StyleSerge, A., Quiroz Montoya, J., Alonso, F., & Montoro, L. (2021). Socioeconomic Status, Health and Lifestyle Settings as Psychosocial Risk Factors for Road Crashes in Young People: Assessing the Colombian Case. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(3), 886. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18030886