Eficacy of Cryotherapy in the Prevention of Oral Mucosistis in Adult Patients with Chemotherapy

Abstract

:1. Introduction

Objectives: Peak Question

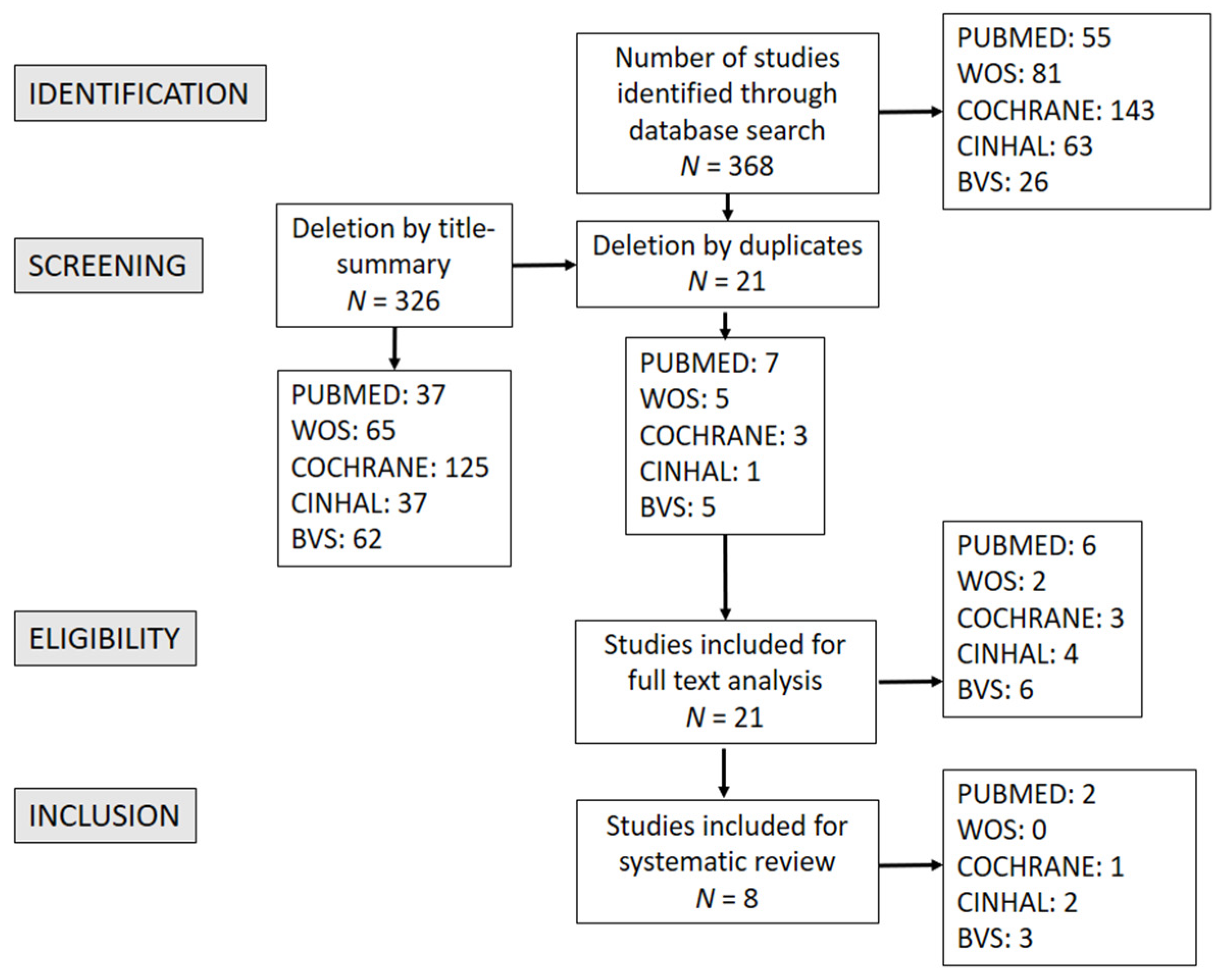

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Information Sources

2.2. Search Strategy

2.3. Inclusion Criteria

2.4. Selection of Studies and Collection of Data

2.5. Assessment of the Quality of Studies: Detection of Possible Bias

2.6. Analysis of Data and Levels of Evidence

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. OC in OM Prevention

4.2. Influence of OC on the Occurrence of Pain in Adult Cancer Patients Treated with Chemotherapy

4.3. Strengths and Limitations

4.4. Implications for Clinical Practice

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Daugėlaitė, G.; Užkuraitytė, K.; Jagelavičienė, E.; Filipauskas, A. Prevention and Treatment of Chemotherapy and Radiotherapy Induced Oral Mucositis. Medicina 2019, 55, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lalla, R.V.; Saunders, D.P.; Peterson, D.E. Chemotherapy or radiation-induced oral mucositis. Dent. Clin. N. Am. 2014, 58, 341–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alvariño-Martín, C.; Sarrión-Pérez, M.G. Prevention and treatment of oral mucositis in patients receiving chemotherapy. J. Clin. Exp. Dent. 2014, 6, e74–e80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Epstein, J.B.; Miaskowski, C. Oral Pain in the Cancer Patient. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. Monogr. 2019, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, M.H.; Villaverde, R.M.; Soto, M.Á.-M. Protocolo de manejo de la mucositis oral en el paciente oncológico. Rev. Educ. Super 2017, 12, 45–53. [Google Scholar]

- Mallick, S.; Benson, R.; Rath, G.K. Radiation induced oral mucositis: A review of current literature on prevention and management. Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 2016, 273, 2285–2293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.H.; Lee, H.S. Meta-analysis of oral cryotherapy in preventing oral mucositis associated with cancer therapy. Int. J. Nurs. Pract. 2019, 25, e12759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ansari, S.; Zecha, J.A.; Barasch, A.; de Lange, J.; Rozema, F.R.; Raber-Durlacher, J.E. Oral Mucositis Induced By Anticancer Therapies. Curr. Oral. Health Rep. 2015, 2, 202–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chaveli-López, B.; Bagán-Sebastián, J.V. Treatment of oral mucositis due to chemotherapy. J. Clin. Exp. Dent. 2016, 8, e201–e209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdelin, M.; Daguindau, E.; Larosa, F.; Legrand, F.; Nerich, V.; Deconinck, E.; Limat, S. Mucositis after allogeneic stem cell transplantation: Risk factors, clinical consequences and prophylaxis. Pathol. Biol. 2015, 63, 106–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lalla, R.V.; Bowen, J.; Barasch, A.; Elting, L.; Epstein, J.; Keefe, D.M.; McGuire, D.B.; Migliorati, C.; Nicolatou-Galitis, O.; Peterson, D.E.; et al. MASCC/ISOO clinical practice guidelines for the management of mucositis secondary to cancer therapy. Cancer 2014, 120, 1453–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Peterson, D.E.; Ohrn, K.; Bowen, J.; Fliedner, M.; Lees, J.; Loprinzi, C.; Mori, T.; Osaguona, A.; Weikel, D.S.; Elad, S.; et al. Systematic review of oral cryotherapy for management of oral mucositis caused by cancer therapy. Support. Care Cancer 2013, 21, 327–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Manzi, N.M.; Silveira, R.C.; dos Reis, P.E. Prophylaxis for mucositis induced by ambulatory chemotherapy: Systematic review. J. Adv. Nurs. 2016, 72, 735–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Svanberg, A.; Ohrn, K.; Birgegård, G. Five-year follow-up of survival and relapse in patients who received cryotherapy during high-dose chemotherapy for stem cell transplantation shows no safety concerns. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2012, 21, 822–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wodzinski, A. Potential Benefits of Oral Cryotherapy for Chemotherapy-Induced Mucositis. Clin. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2016, 20, 462–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadakia, K.C.; Rozell, S.A.; Butala, A.A.; Loprinzi, C.L. Supportive cryotherapy: A review from head to toe. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2014, 47, 1100–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso-Ribero, C.; Gómez-Conesa, A.; Hidalgo-Montesinos, M. Metodología para la adaptación de instrumentos de evaluación. Fisioterapia 2011, 32, 264–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, F.C.; Arancibia, B.V.; Iop, R.R.; Gutierres Filho, P.J.B.; Silva, R. Escalas y listas de evaluación de la calidad de estudios científicos. Evaluation lists and escales for the quiality of scientific studies. Rev. Cuba. Inf. Cienc. Salud 2015, 24, 295–312. [Google Scholar]

- Jovell, A.; Navarro-Rubio, M. Evaluación de la evidencia científica. Med. Clin. 1995, 105, 740–743. [Google Scholar]

- Marchesi, F.; Tendas, A.; Giannarelli, D.; Viggiani, C.; Gumenyuk, S.; Renzi, D.; Franceschini, L.; Caffarella, G.; Rizzo, M.; Palombi, F.; et al. Cryotherapy reduces oral mucositis and febrile episodes in myeloma patients treated with high-dose melphalan and autologous stem cell transplant: A prospective, randomized study. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2017, 52, 154–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Reis, P.E.; Ciol, M.A.; de Melo, N.S.; Figueiredo, P.T.; Leite, A.F.; Manzi, N.M. Chamomile infusion cryotherapy to prevent oral mucositis induced by chemotherapy: A pilot study. Support. Care Cancer 2016, 24, 4393–4398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erden, Y.; Ipekcoban, G. Comparison of efficacy of cryotherapy and chlorhexidine to oral nutrition transition time in chemotherapy-induced oral mucositis. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2017, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Svanberg, A.; Öhrn, K.; Birgegård, G. Caphosol(®) mouthwash gives no additional protection against oral mucositis compared to cryotherapy alone in stem cell transplantation. A pilot study. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2015, 19, 50–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okamoto, K.; Ninomiya, I.; Yamaguchi, T.; Terai, S.; Nakanuma, S.; Kinoshita, J.; Makino, I.; Nakamura, K.; Miyashita, T.; Tajima, H.; et al. Oral cryotherapy for prophylaxis of oral mucositis caused by docetaxel, cisplatin, and fluorouracil chemotherapy for esophageal cancer. Esophagus 2019, 16, 207–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batlle, M.; Morgades, M.; Vives, S.; Ferrà, C.; Oriol, A.; Sancho, J.-M.; Xicoy, B.; Moreno, M.; Magallón, L.; Ribera, J.-M. Usefulness and safety of oral cryotherapy in the prevention of oral mucositis after conditioning regimens with high-dose melphalan for autologous stem cell transplantation for lymphoma and myeloma. Eur. J. Haematol. 2014, 93, 487–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nawi, R.I.M.; Chui, P.L.; Ishak, W.Z.W.; Chan, C.M.H. Oral Cryotherapy: Prevention of Oral Mucositis and Pain Among Patients with Colorectal Cancer Undergoing Chemotherapy. Clin. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2018, 22, 555–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Seabrook, J.; Fulford, A.; Rajakumar, I. Icing oral mucositis: Oral cryotherapy in multiple myeloma patients undergoing autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplant. J. Oncol. Pharm. Pract. 2017, 23, 116–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Criterion (PICO) | Keywords |

|---|---|

| Population (P) | (“patients’ cancer”) and (“oral mucositis”) and (“chemotherapy”) and (“radiotherapy”) |

| Intervention (I) | oral cryotherapy |

| Outcome (O) | OM prevention OR patient´s benefits |

| Author—Year | Type of Study | Type of Intervention | Sample Size |

|---|---|---|---|

| Marchesi F. et al., 2017 [20] | Randomization method: it is based on two groups (experimental and control). Place: Hospital Sant’Eugenio in Roma (Italy). Participants were not blinded. All patients signed a written informed consent, and the study was approved by the Ethical Committee, in compliance with the Helsinki declaration. | From October 2013 to January 2016, patients were enrolled in this study. CG: oral standard care. EG: after IV melphalan administration, on day-2, patients in EG received ice chips with rounded corners in their mouth during chemotherapy infusion. When the ice melted, it was immediately replaced. OM was assessed daily using the National Cancer Institute Common Toxicity Criteria version 4.02. Patient pain due to OM was monitored daily using the numerical rating scale. In case of severe and uncontrolled pain, IV opioids were administered. All patients (EG and CG) underwent uniform anti-infectious and support therapy (ciprofloxacin, cotrimoxazole, and valaciclovir). All patients (EG and CG) underwent mouth rinses with oral nystatin-based protocols three times daily. Patients were hospitalized and remained as inpatients for the duration of the study. No data on how long patients received chemotherapy or how long after therapy when some degree of OM appeared. | N = 72 (36 EG, 36 CG), 46 males, 26 females. Inclusion criteria: Patients aged ≥18 years, with multiple myeloma undergoing HSCT after being treated with high doses of melphalan. Exclusion criteria: Patients who had experienced previous episodes of OM or with previous exposure to chemotherapy or neck/head radiotherapy were excluded. Characteristics: age (EG: 58 ± 13.5; CG: 56 ± 17). |

| Diniz et al., 2016 [21] | Randomization method: it is based on two groups (experimental and control). Place: Hospital Center of High Complexity Oncology del Hospital Universitario en Brasilia (Brasil). Only the doctor was blinded to randomization. Patients were not possible to blind. All patients provided written consent prior to starting the procedures. The study was approved by the Committee on Ethics Research of the School of Health Sciences of the University of Brasília. | Between March 2012 and March 2015, patients were invited to participate in the study. The study interventions were performed only during the first 5 days of the first cycle of chemotherapy. Patients who agreed to participate in the study watched a video explaining how to perform oral hygiene and received an oral hygiene kit (toothbrush, nonabrasive toothpaste, and dental floss). During chemotherapy treatment, the following were administered prophylactically: CG: OC with only water was administered prophylactically. EG: Patients in the control group received a cup of ice chips made with pure water, while patients in the chamomile group received a cup of ice chips made with chamomile infusion at 2.5%. Both groups were instructed to swish the ice around in their oral cavity for at least 30 min, starting 5 min before the chemotherapy infusion. During the intervention, patients were asked to fill a questionnaire about ice taste, discomfort, and pain regarding cryotherapy. A doctor evaluated the oral mucosa on days 8, 15, and 22 after the first chemotherapy infusion. Patients underwent four to six courses of chemotherapy, each consisting of five consecutive days of chemotherapy infusion, followed by 21 days of rest. The study interventions were performed only during the 5 days of the first course. No data showing how long after therapy before some degree of OM appeared. | N = 38 (20 EG—11 males, 9 females, 18 CG—9 males, 9 females). Inclusion criteria: elderly patients with gastric or colorectal cancer who received ambulatory IV chemotherapy for the first time (5-fluorouracil and leucovorin). Intact and healthy oral mucosa, without dental problems, and without a history of hypersensibility or adverse reaction to chamomile or any plant of the Asteraceae or Compositae family. Characteristics: age EG: 54.7 (SD 8.15); CG: 55.2 (SD 9.5). |

| Erden et al., 2017 [22] | Randomization method: it is based on three groups (2 experimental and 1 control). Place: Erzurum Ataturk University Research and Application Hospital in Erzurum (Turkey). Participants were not blinded. Oral consent was obtained from the patients for their participation in the study before the questionnaire forms were administered. The patients were also informed verbally about the study. Participation was voluntary, and the patients could withdraw from the study at any time without giving a reason. Approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee of the Medical Faculty, Ataturk University. | The observation period was 15 days for each participant. During chemotherapy treatment, the following were administered prophylactically: EG1: received chlorhexidine mouthwash. EG2: OC with only water was administered prophylactically. CG: standard oral care. EG1 data were collected from patients in the study groups who had oral care with chlorhexidine twice a day; EG2 had cryotherapy once a day. Chlorhexidine mouthwash was applied six times a day to patients with Grade III oral mucositis, and it was applied eight times a day to patients with Grade IV oral mucositis. Tooth brushing is not recommended to patients with Grade III and IV oral mucositis because of possible ulcerations due to physical irritation. CG data were collected from patients who followed standard oral care protocol (washing with plenty of water mouthwash). The duration of the patient’s disease was 4–9 or more months, and the duration of cancer therapy was 1–9 months. No data showing how long patients received chemotherapy or how longafter chemotherapy before some degree of OM appeared. | N = 90 (30 EG1, 30 EG2, 30 CG). Inclusion criteria: All subjects had Grade III–IV oral mucositis due to chemotherapy received for various types of cancer, and all of them were unable to take food orally. Exclusion criteria were not named. |

| Svanberg et al., 2015 [23] | Randomization method: it is based on three groups (2 experimental and 1 control). Place: Akademiska University Hospital in Uppsala (Sweden). Participants were not blinded. The study was approved by the regional Research Ethics Committee. | From September 2010 and October 2011, patients were enrolled in this study. During chemotherapy treatment, the following were administered prophylactically: CG: OC with only water was administered prophylactically. EG: OC + Caphosol® was administered prophylactically. OC was given in the form of ice cubes or crushed ice to be kept in the mouth during the actual infusion of the HSCT. Thirty (30) mL Caphosol® was administrated for rinsing the whole oral cavity four times/day, starting prior to HSCT and ending on day 21. All patients received intravenous conditioning chemotherapy based on diagnosis. The average duration of chemotherapy treatment, depending on the type of cancer, was 4 days. No data showing how long before some degree of OM appeared. | N = 40 (20 EG—11 males, 9 females, 18 CG—9 males, 9 females). Inclusion criteria: patients >16 years, with various types of cancer (acute myeloid leukemia, acute lymphoblastic leukemia, chronic lymphatic leukemia, chronic myeloid leukemia, chronic myelomonocytic leukemia, myelodysplastic syndrome), undergoing HSCT after being treated with chemotherapy and radiotherapy. All patients received intravenous conditioning chemotherapy and (when required) total body irradiation on the basis of diagnosis. Exclusion criteria were not named. Characteristics: age between 17 and 67 years (p > 0.05; EG: 50.4 ± 10.6; CG: 59.6 ± 13.2) |

| Idayu et al., 2018 [24] | Randomization method in two groups: experimentation and control. Place: University of Malaya Medical Centre in Kuala Lumpur (Malaysia). Participants were not blinded. All patients provided informed consent and were ensured of the confidentiality of their participation. The study was approved by the Ethical Committee. | During treatment with chemotherapy (fluorounacil), the following was administered prophylactically: CG: standard care and rinses with sodium bicarbonate were administered prophylactically. EG: were given ice chips to hold in their mouths for 30 min during chemotherapy administration (the ice chips were replenished as they melted, and patients were instructed to move the ice in an attempt to keep the entire oral cavity cold), followed by sodium bicarbonate mouthwash (three times daily) postchemotherapy until the next cycle. No data showing the duration of the study, how long patients received chemotherapy, or how long after therapy before some degree of OM appeared | N = 80 (40 EG—22 men, 18 women, 40 CG—23 men, 17 women) Inclusion criteria: patients >20 years old with colorectal cancer, scheduled for fluorouracil-based chemotherapy at their first cycle of chemotherapy. According to the Eilers scale (1988), only patients with scores ranging from 1–8 were recruited into the study. Characteristics: age: between 20 and 60 years (mean = 48.4, SD = 9.2; p > 0.05). |

| Batlle et al., 2014 [25] | Retrospective cohort study. Randomization method in two groups: experimentation and control. Location: not specified. | From August 2006 to July 2011, 134 consecutive patients were enrolled in the study. All participants underwent an oral care protocol consisting of a sodium bicarbonate mouthwash from day 7 of HSCT to hospital discharge. CG: standard care and rinses with sodium bicarbonate were administered prophylactically. EG: OC consisted of ice chips sucked on before infusion (10 min), during infusion (15 min), and after chemotherapy administration for a total of 40 min. and then mouthwashes with sodium bicarbonate up to hospital discharge. The mean time to the initiation and the duration of OM did not differ among groups (2.50 and 9.20 days, respectively). No data on how long the patients received chemotherapy. | N = 134 (66 EG—47 men, 19 women, 68 CG—39 men, 29 women) (p = 0.094). Inclusion criteria: patients >20 years old, with hematological cancer treated with chemotherapy (high-dose melphalan (HDmel)) and HSCT. Characteristics: age between 23 and 70 years old. EG: 56 (23–69), CG: 55 (25–70) (p > 0.05). |

| Okamoto et al., 2019 [26] | Retrospective cohort study. Randomization method in two groups: experimentation and control. Place: Department of Gastroenterological Surgery, Kanazawa University (Japan). All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation and the Helsinki Declaration of 1964 and later versions. Informed consent or a substitute for it was obtained from all patients included in the study. | From March 2011 and July 2016, patients were enrolled in this study. CG: did not receive OC. EG: OC performed routinely for patients receiving chemotherapy. The patients were instructed to suck continuously on several pieces of ice from 10 min before until after the end of the chemotherapy infusion. The chemotherapy (cisplatin, 5-fluorouracil) was administered for 1–5 days, repeated every 4 weeks. No data showing how long before some degree of OM appeared. | N = 72 (58 EG—50 men, 8 women; CG 14—12 men, 2 women) (p > 0.999) Inclusion criteria: patients with primary esophageal cancer staged according to the 7th edition of the tumor-node-metastasis (TNM) classification of malignant tumors and treated with chemotherapy prior to surgery. Characteristics: age between 57 and 71 years old. EG: 64.0 (57.0–69.0). CG: 64.5 (57.3–70.5) (p > 0.05). |

| Chen et al., 2017 [27] | Retrospective cohort study. Randomization method in two groups: experimentation and control. Place: Victoria Hospital, London Health Sciences Center (UK). Participants were not blinded. The study protocol was approved by the Office of Research Ethics at the University of Western Ontario, Lawson Health Research Institute. Due to the retrospective nature of the study, no patient consent was required. | The study examined patients over the span of seven years, from 2006 to 2013. Medical charts of consecutive patients with multiple myeloma undergoing autologous HSCT, admitted over the period of 2006 to 2013, were reviewed. Two groups of patients were compared in this study analysis: CG: patients treated with chemotherapy between 2007 and 2009 who did not receive OC until 2010. EG: OC performed routinely for patients receiving chemotherapy from 2010 to 2013. Patients were instructed to hold ice chips in their mouth for 5 min prior to high-dose melphalan infusion, during the 30-min infusion, and 30 min after completion of the infusion. The conditioning regimen of chemotherapy (high-dose melphalan) was administered 2 days before the transplant date. No data showing how long before some degree of OM appeared. The duration of OM in mean days was 10.1–7.8 (SD 4.9 ± 6.2, respectively). | N = 140 (70 EG—56 men, 14 women; CG 70—38 men, 22 women) (p = 0.01). Inclusion criteria: patients >18 years old, with lymphoma and multiple myeloma, receiving high-dose chemotherapy (mephalan) for HSCT. Characteristics: age between 57 and 71 years old. EG: 53.5 (±7.5),; CG: 56.5 (±7.3) (p = 0.02). |

| Author—Year | Results | Conclusions | Quality |

|---|---|---|---|

| Marchesi F et al., 2017 [20] | Occurrence of Grade III–IV OM (%): EG: 5.6; CG: 44 (p = 0.0002). Occurrence of any grade OM (%): EG: 16; CG: 58.3 (p = 0.001). Need for opioid IV therapy (%): EG: 2.8; CG: 33.3 (p = 0.001). | The study provided relevant data to support OC during HDM administration as the standard of care in preventing OM in myeloma patients undergoing HSCT. | 9/11 |

| Diniz et al., 2016 [21] | EG patients never presented OM ≥ Grade 2 (p > 0.005). OM appearance in any degree: EG: 30%; CG: 50% (p = 0.01). Mouth pain: EG had less mouth pain than CG (p > 0.05). | The infusion of OC with chamomile reduces the appearance of OM compared to OC with water alone; it also reduces mucosal pain. The occurrence of OM was lower in patients who used OC made with chamomile infusion than in patients who used OC made only with water. When compared to the control group, the chamomile group presented less mouth pain and had no ulcerations. OC was well tolerated by both groups, and no toxicity was identified. | 9/11 |

| Erden et al., 2017 [22] | Oral nutrition transition time in days (mean ± SD) EG1: 8.53 ± 1.04. There was a statistical difference between experimental group 1 and the control group (p < 0.01). EG2: 12.13 ± 1.81. There was no statistical difference between experimental group 2 and the control group (p > 0.05). CG: 13.53 ± 1.69. There was no statistical difference between experimental group 2 and the control group (p > 0.05). | The analysis of this study showed that the transition time of oral nutrition of the patients in the experimental group that applied chlorhexidine was shorter than the transition time of oral nutrition of the patients of the group that applied OC; in both experimental groups (EG1 and EG2), transitional time was shorter than the control group. Parallel to this finding, it was found that the degree of OM was reduced. According to this result, using chlorhexidine or OC mouthwash for the prevention and treatment of oral mucosis should be offered. | 8/11 |

| Svanberg et al., 2015 [23] | There is no difference between EG and CG in the degree of OM at day 21 of treatment (2.45 vs. 2.30 on average, according to the WHO scale; p > 0.05). The perception of oral pain in both groups, assessed with the visual analog scale, showed no difference (3.55 vs. 2.7 on the visual analog scale; p > 0.05). | No additional significant effect of combining Caphosol® with OC in the prevention and treatment of OM. | 9/11 |

| Idayu et al., 2018 [24] | The appearance of OM was as follows (p < 0.05): EG: 29 participants did not present OM (Grade 0), 11 did (Grade I); CG: 38 participants presented OM of Grade II or higher. In the EG, 27 indicated no pain, while 38 of the CG indicated moderate to severe pain. Pain associated with OM (p > 0.005): EG: 27 participants reported no pain; CG: 18 participants reported moderate pain and 20 participants reported severe pain. | OC followed by bicarbonate-based mouthwash could help prevent oral mucositis and pain. This finding helps shed light on evidence supporting the use of oral cryotherapy, which is cost-effective and has few side effects, as a preventive strategy. OC is easily implemented in tandem with the use of a sodium bicarbonate mouthwash. The potential benefit of cryotherapy in the prevention of oral mucositis and the associated pain appears to improve the quality of life of patients undergoing fluorouracil-based chemotherapy. | 8/11 |

| Batlle et al., 2014 [25] | Population who developed OM to any degree: EG: 44% vs. CG 82% (p < 0.001). The incidence of OM Grades III and IV: EG: 15% vs. CG: 31% (p = 0.031). Opiates were required in EG: 10% and CG: 15% (p = 0.305). | The authors indicated although this was a nonrandomized study and the conditioning regimens were not homogeneous, OC reduced the severity of OM in patients treated with regimens compared with saline rinses. Additionally, OC was cost-effective and well tolerated by the patients. In summary, OC represents an effective and inexpensive supportive measure to prevent OM induced by HDmel-based regimens. | 7/11 |

| Okamoto et al., 2019 [26] | The incidences of OM Grades I–III was 71.4% (CG) and 24.1% (EG); p = 0.001. The incidence of Grade III OM was also lower: EG 0% vs. CG 28.6%; p = 0.001. | OC may be a useful prophylactic approach for chemotherapy-induced OM in patients with esophageal cancer. | 8/11 |

| Chen et al., 2017 [27] | The incidence of OM was significantly lower in the EG than in the CG (71.4% vs. 95.7%; p < 0.001). The mean degree of OM in the CG vs. the EG was higher (2.5 vs. 2; p = 0.03. The use of parenteral analgesics was significantly lower in the EG (25.7%) than in the CG (44.2%), p = 0.02. | OC protocol implemented at HSCT resulted in significantly lower incidences and severity of oral mucositis. The mean duration of oral mucositis experienced by patients was shortened, and the need for the use of parenteral narcotics was decreased as well. These results provide evidence for the continued use of oral cryotherapy, an inexpensive and generally well-tolerated practice, in patients receiving high-dose melphalan for autologous HSCT. | 8/11 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

López-González, Á.; García-Quintanilla, M.; Guerrero-Agenjo, C.M.; Tendero, J.L.; Guisado-Requena, I.M.; Rabanales-Sotos, J. Eficacy of Cryotherapy in the Prevention of Oral Mucosistis in Adult Patients with Chemotherapy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 994. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18030994

López-González Á, García-Quintanilla M, Guerrero-Agenjo CM, Tendero JL, Guisado-Requena IM, Rabanales-Sotos J. Eficacy of Cryotherapy in the Prevention of Oral Mucosistis in Adult Patients with Chemotherapy. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(3):994. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18030994

Chicago/Turabian StyleLópez-González, Ángel, Marta García-Quintanilla, Carmen María Guerrero-Agenjo, Jaime López Tendero, Isabel María Guisado-Requena, and Joseba Rabanales-Sotos. 2021. "Eficacy of Cryotherapy in the Prevention of Oral Mucosistis in Adult Patients with Chemotherapy" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 3: 994. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18030994

APA StyleLópez-González, Á., García-Quintanilla, M., Guerrero-Agenjo, C. M., Tendero, J. L., Guisado-Requena, I. M., & Rabanales-Sotos, J. (2021). Eficacy of Cryotherapy in the Prevention of Oral Mucosistis in Adult Patients with Chemotherapy. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(3), 994. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18030994