Persistent Suffering: The Serious Consequences of Sexual Violence against Women and Girls, Their Search for Inner Healing and the Significance of the #MeToo Movement

Abstract

:1. Introduction

Theoretical Background

2. Materials and Methods

Steps in the Theory Synthesis

3. Results

3.1. Consequences of Sexual Violence in Childhood

3.2. Consequences of Sexual Violence during Adolescence

3.3. Consequences of Sexual Violence in Adulthood

3.4. The Challenging Journey in Search of Inner Healing after Sexual Violence

3.5. The Results in a Nutshell

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mendes, K.; Ringrose, J.; Keller, J. #MeToo and the promise and pitfalls of challenging rape culture through digital feminist activism. Eur. J. Women’s Stud. 2018, 25, 236–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ramona, A. International Women’s Day Q & A: Ramona Alaggia on researching the impact of the #MeToo Movement in Canada. In Factor-Inwentash; Faculty of Social Work, University of Toronto: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Morrison-Beedy, D.; Grove, L. Adolescent girls’ experiences with sexual pressure, coercion, and victimization: #MeToo. Worldviews Evid. Based Nurs. 2018, 15, 225–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- McBride, B.; Mitra, S.; Kondo, V.; Elmi, H.; Kamal, M. Unpaid labour, #MeToo, and young women in global health. Lancet 2018, 391, 2192–2193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antoni, M.H. Stress management, PNI, and disease. In Stress Management, PNI, and Disease; Segerstrom, S.C., Ed.; Oxford University Press (OUP): Oxford, UK, 2012; pp. 385–420. [Google Scholar]

- Kendall-Tackett, K.; Marshall, A.R.; Ness, K.E. Victimization, healthcare use, and health maintenance. Fam. Viol. Sex. Assault Bull. 2000, 16, 18–21. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno-Ramos, O.A.; Lattig, M.C.; Barrios, A.F.G. Modeling of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis-mediated interaction between the serotonin regulation pathway and the stress response using a Boolean Approximation: A novel study of depression. Theor. Biol. Med. Model. 2013, 10, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McEwen, B.S. Protective and damaging effects of stress mediators: Allostasis and allostatic load. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003, 228, 171–179. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, Q. Psychoneuroimmunology: Systems Biology Approaches to Mind-Body Medicine; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Slavich, G.M.; Irwin, M.R. From stress to inflammation and major depressive disorder: A social signal transduction theory of depression. Psychol. Bull. 2014, 140, 774–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maesa, M.; Ruckoanich, P.; Chang, Y.S.; Mahanonda, N.; Berk, M. Multiple aberrations in shared inflammatory and oxidative & nitrosative stress (IO&NS) pathways explain the co-association of depression and cardiovascular disorder (CVD), and the increased risk for CVD and due mortality in depressed patients. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2011, 35, 769–783. [Google Scholar]

- Nikkheslat, N.; Zunszain, P.A.; Horowitz, M.A.; Barbosa, I.G.; Parker, J.A.; Myint, A.-M.; Schwarz, M.J.; Tylee, A.T.; Carvalho, L.A.; Pariante, C.M. Insufficient glucocorticoid signaling and elevated inflammation in coronary heart disease patients with comorbid depression. Brain, Behav. Immun. 2015, 48, 8–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Littrell, J. The mind-body connection: Not just a theory anymore. Soc. Work. Health Care 2008, 46, 17–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slavic, G.M. Life and stress and health: A review of conceptual issues and recent findings. Teach. Psychol. 2016, 43, 346–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Segerstrom, S.C. Looking into the Future: Conclusion to the Oxford Handbook of Psychoneuroimmunology; Oxford University Press (OUP): Oxford, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, K.A.; Melhorn, S.J.; Sakai, R.R. Effects of chronic social stress on obesity. Curr. Obes. Rep. 2012, 1, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Rasmusson, A.M.; Schnurr, P.P.; Zukowska, Z.; Scioli, E.; E Forman, D. Adaptation to extreme stress: Post-traumatic stress disorder, neuropeptide Y and metabolic syndrome. Exp. Biol. Med. 2010, 235, 1150–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar-Valles, A.; Inoue, W.; Rummel, C.; Luheshi, G.N. Obesity, adipokines and neuroinflammation. Neuropharmacology 2015, 96, 124–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaremka, L.M.; Lindgren, M.E.; Kiecolt–Glaser, J.K. Synergistic relationships among stress, depression, and troubled relationships: Insights from psychoneuroimmunology. Depress. Anxiety 2013, 30, 288–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, Q. Translational implications of inflammatory biomarkers and cytokine networks in psychoneuroimmunology. Adv. Struct. Saf. Stud. 2012, 934, 105–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, G.E.; Freedland, K.E.; Carney, R.M.; Stetler, C.A.; Banks, W.A. Pathways linking depression, adiposity, and inflammatory markers in healthy young adults. Brain Behav. Immun. 2003, 17, 276–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, L.O.; Avant, K.C. Strategies for Theory Construction in Nursing, 6th ed.; Pearson: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Sigurdardottir, S.; Halldorsdottir, S. Time does not heal all wounds. [Timarit hjukrunarfraedinga] Icel. J. Nurs. 2009, 85, 38–50. [Google Scholar]

- Kristinsdottir, A.; Halldorsdottir, S. Constant stress, fear, and anxiety: The experiences of women who have experienced violence during pregnancy and at other times. [Ljosmaedrabladid] Icel. J. Midwifery 2010, 88, 6–12. [Google Scholar]

- Sigurdardottir, S.; Halldorsdottir, S. Silent suffering: Long-term consequences of sexual violence in youth for health and well-being of men and women. In The Secret Crime; Olafsdottir, S.I., Ed.; Haskolautgafan: The University Publishing House: Reykjavík, Iceland, 2011; pp. 317–353. [Google Scholar]

- Sigurdardottir, S.; Halldorsdottir, S. Repressed and silent suffering: Consequences of childhood sexual abuse for women’s health and well-being. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2012, 27, 422–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sigurdardottir, S.; Halldorsdottir, S.; Bender, S.S. Consequences of childhood sexual abuse for health and well-being: Gender similarities and differences. Scand. J. Public Health 2013, 42, 278–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigurdardottir, S.; Halldorsdottir, S. Screaming body and silent healthcare providers: A case study with a childhood sexual abuse (CSA) survivor. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigurdardottir, S.; Halldorsdottir, S.; Bender, S.S.; Agnarsdottir, G. Personal resurrection: Female childhood sexual abuse survivors’ experience of the Wellness-Program. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2016, 30, 175–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigurdardottir, S. Childhood sexual abuse: Consequences and Holistic Intervention. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Iceland, Reykjavik, Iceland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhlman, K.R.; Chiang, J.J.; Horn, S.; Bower, J.E. Developmental psychoneuroendocrine and psychoneuroimmune pathways from childhood adversity to disease. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2017, 80, 166–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagundes, C.P.; Glaser, R.; Kiecolt-Glaser, J.K. Stressful early life experiences and immune dysregulation across the lifespan. Brain, Behav. Immun. 2013, 27, 8–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nelson, S.; Baldwin, N.; Taylor, J. Mental health problems and medically unexplained physical symptoms in adult survivors of childhood sexual abuse: An integrative literature review. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2011, 19, 211–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonomi, A.E.; Anderson, M.L.; Rivara, F.P.; Cannon, E.A.; Fishman, P.A.; Carrell, D.; Reid, R.J.; Thompson, R.S. Healthcare utilization and costs associated with childhood abuse. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2008, 23, 294–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Machtinger, E.L.; Cuca, Y.P.; Khanna, N.; Rose, C.D.; Kimberg, L.S. From treatment to healing: The promise of trauma-informed primary care. Women’s Health Issues 2015, 25, 193–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moraes, L.J.; Miranda, M.B.; Loures, L.F.; Mainieri, A.G.; Mármora, C.H.C. A systematic review of psychoneuroimmunology-based interventions. Psychol. Health Med. 2018, 23, 635–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogen, K.W.; Bleiweiss, K.; Orchowski, L.M. Sexual violence is #NotOkay: Social reactions to disclosures of sexual victimiza-tion on Twitter. Psychol. Viol. 2019, 9, 127–137. [Google Scholar]

- Justice, B. Suffering in silence and the fear of social stigma. In The Hidden Dimension of Illness: Human Suffering; Starck, P.L., McGovern, J.P., Eds.; National League for Nursing Press: New York, NY, USA, 1992; pp. 269–289. [Google Scholar]

- Pennebaker, J.W. Emotion, Disclosure, and Health: An Overview; American Psychological Association (APA): Washington, DC, USA, 1995; pp. 3–10. [Google Scholar]

- Kearns, M.C.; Edwards, K.M.; Calhoun, K.S.; Gidycz, C.A. Disclosure of sexual victimization: The effects of Pennebaker’s emotional disclosure paradigm on physical and psychological distress. J. Trauma Dissociation 2010, 11, 193–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Booth, R.J. Emotional expression, and disclosure. In The Oxford Handbook of Psychoneuroimmunology; Segerstrom, S.C., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2012; pp. 105–125. [Google Scholar]

- Fairbaim, J. Before #MeToo: Violence against women, social media work, bystander intervention, and social change. Societies 2020, 10, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchino, B.N. Social Support and Physical Health: Understanding the Health Consequences of Relationships; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Holt-Lunstad, J.; Smith, T.B.; Layton, B. Social relationships and mortality risk: A meta-analytic review. PLoS Med. 2010, 7, e1000316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kameg, B.N.; Constantino, R.E. #MeToo and ‘Time’s Up’: Implications for psychiatric and mental health nurses. J. Am. Psy-chiatr. Nurses Assoc. 2018, 24, 188–189. [Google Scholar]

- O’Neil, A.; Sojo, V.; Fileborn, B.; Scovelle, A.J.; Milner, A. The #MeToo movement: An opportunity in public health? Lancet 2018, 391, 2587–2589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefansdottir, H. Visits to the emergency departments increase due to the #MeToo movement. Icel. J. Nurs. 2018, 94, 48–49. [Google Scholar]

- Hegarty, K.; Tarzia, L. Identification and management of domestic and sexual violence in primary care in the #MeToo era: An update. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2019, 21, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Step | Description | Overview of What the Authors Did |

|---|---|---|

| Step 1 | The main concepts and main descriptions specified from the studies used. | We used our own databases and analyses of them as a basis for the theory synthesis. These are studies on the consequences of sexual violence against women and girls, as well as their search for internal healing following such violence (see Table 2). |

| Step 2 | In what has been written before, we look for items related to the main concepts or main descriptions and examine the relationship. | We used the table from step one (Table 2) and compared it with research results in peer-reviewed journals where the consequences of sexual violence against women and girls were examined from the perspective of the women themselves. Keywords from the results of Step 1 were used and, with constant comparison, it was possible to examine the consequences of sexual violence against women and girls. Many of the articles were directly related to the consequences of sexual violence for female survivors, while others were only partially related, but could provide important information nonetheless. There was no change due to research in the field of the consequences of sexual violence on women, but research results from psychoneuroimmunology gave more depth to the results. |

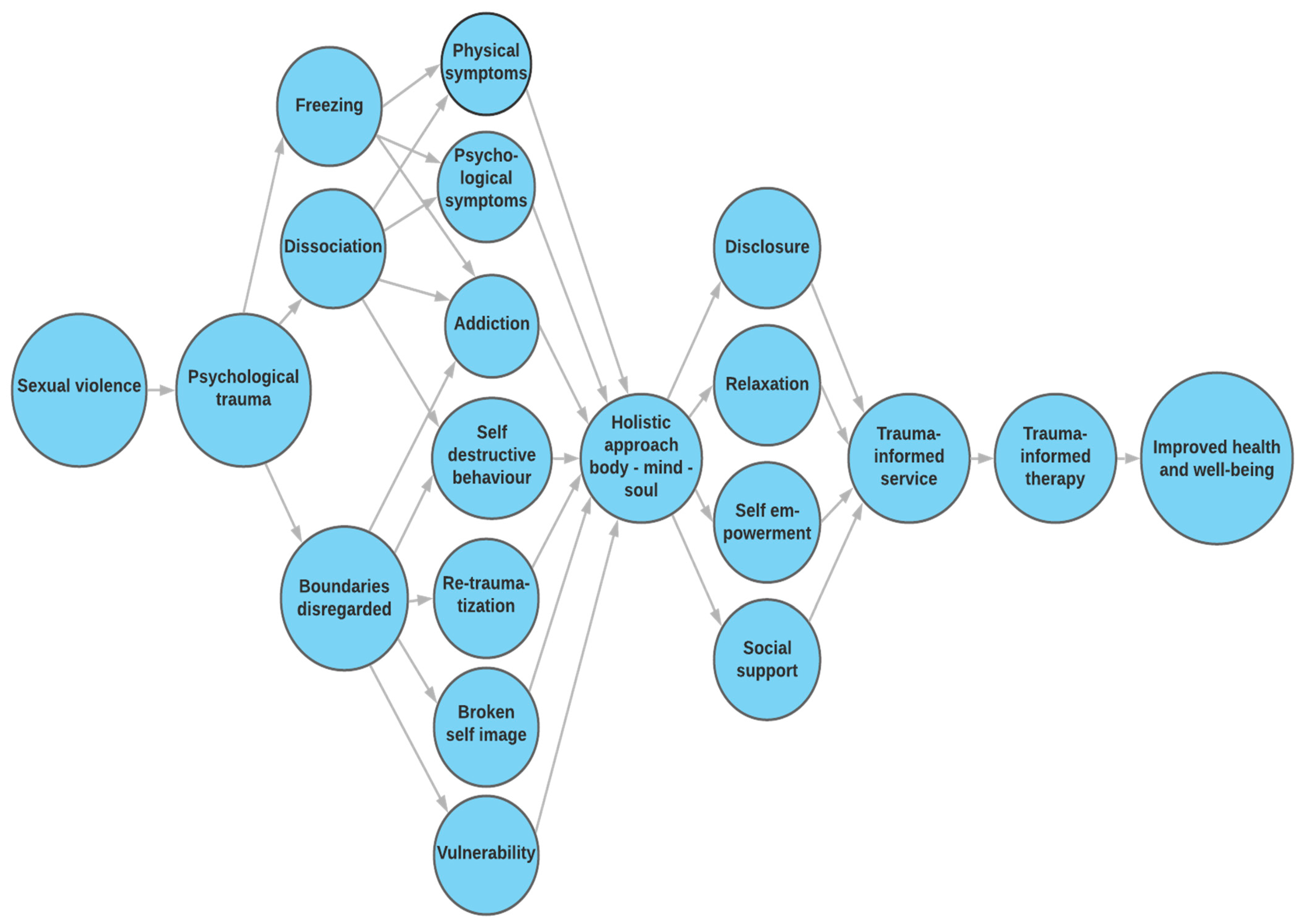

| Step 3 | The concepts and descriptions that pertain to what the theory is about are systematically grouped together and presented in the text, in table(s) or in figure(s). | After compiling detailed descriptions of the consequences of sexual violence on women and girls, we presented the results in the text and in a figure (Figure 1). The text describes the consequences of sexual violence in childhood, during adolescence and in adulthood. The consequences are physical, mental, and social. The figure describes the consequences of sexual violence on women and girls and how the unity of mind, body and soul must be considered when considering treatment. |

| Our Studies | Key Conclusions for the Theory |

|---|---|

| 1. Sigurdardottir, S.; Halldors-dottir, S. Time does not heal all wounds [23]. | Consequences of violence against women: Physical symptoms: multiple health problems in the lower abdomen, widespread and chronic pain, sleeping problems, eating disorders (especially obesity), fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue, cardiovascular problems, and diabetes. Psychiatric symptoms: depression (and postpartum depression), anxiety, stress, fear, poor self-esteem, shame, guilt, self-harming behavior, alcohol and drug abuse, severe suicidal ideation; anger, sadness, melancholy, and disappointment; personality disorder, trauma disorder and social phobia. Social symptoms: difficulty with touch, sex and relationships with spouses, difficulty trusting men, exposure to all kinds of violence in adulthood, recurring physical, mental and/or sexual violence in a relationship or rape; great anxiety, stress and strain as a parent; seeking health services on a large scale but not reporting the violence—receiving little support but a large amount of medication. |

| 2. Kristinsdottir, A.; Halldors-dottir, S. Constant stress, fear, and anxiety: The experience of women who have experienced intimate partner violence during pregnancy and at other times [24]. | Consequences of violence against women: Constant stress, fear, fright and anxiety; depression and great distress; increased violence during pregnancy; postpartum depression; broken self-confidence and decreased self-esteem; heavy flashbacks, difficult memories and nightmares; loneliness and isolation; guilt and shame; severe physical symptoms and eating disorders; feeling they cannot stand by themselves; difficulty trusting others; strong feelings of rejection. |

| 3. Sigurdardottir, S.; Halldors-dottir, S. Silent suffering: Long-term consequences of sexual violence in youth for health and well-being of men and women [25]. | Consequences of violence against women: In childhood: emotional pain, agony and anguish; always alert, always expecting something bad and felt their personal defenses had been broken down; self-blame and guilt; great secrecy, intimidation and humiliation; dissociation of body and soul; great fear and constant insecurity; not reporting the violence and receiving even more violence if they try. Adolescence was characterized by bullying and great distress; much teasing, few or no friends, isolation; directed their emotions inward and were repressed; usually experienced learning difficulties, dyslexia and attention deficit; most tried to be invisible; lived in constant fear; some started to use alcohol during adolescence to numb their emotional pain; had a variety of physical problems, e.g., myositis and pain, gastritis, migraine, headache, gastrointestinal problems, dizziness and fainting. Some engaged in self-harming behaviors and had suicidal thoughts, and some made suicide attempts. In adulthood: many problems in the lower abdomen, unexplained pain; difficulty sleeping, myositis, anxiety and depression, trying to numb the inner pain by using food, alcohol or drugs; self-destructive behavior, self-harming behavior; a strong feeling of rejection; escape, fear and isolation; severe, unexplained malaise; very broken self-image; little to no self-confidence and self-esteem; enormous emotional pain; failing to keep a job; many are on disability allowance. |

| 4. Sigurdardottir, S.; Halldors-dottir, S. Repressed and silent suffering: Consequences of childhood sexual abuse for women’s health and well-being [26]. | Consequences of violence against women: In childhood: They always felt “different” after the violence. Could not sleep at night and struggled with multiple psychological problems. Experienced attention deficit or attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). In adolescence: A difficult adolescence. Eating disorders. Drinking alcohol very young. Thoughts of suicide and, in some cases, suicide attempts. In adult years: Severe pain in the uterine area. Rheumatoid arthritis. Felt they lost the joy of life and the will to live following the violence. Depression. Always tired and lacking in energy. Strong feeling of rejection. Phobia and isolation. Difficulty maintaining normal relationships with others. Marriage problems. |

| 5. Sigurdardottir, S.; Halldors-dottir, S.; Bender, S.S. Consequences of childhood sexual abuse for health and well-being: Gender similarities and differences [27]. | Consequences of violence against women: In childhood: Their emotional pain was directed inward and caused inner agony and despair, as well as deep and silent suffering. They experienced disconnection between their body and soul as well as great secrecy, threat, fear, and humiliation. They were always insecure, felt the need to be constantly vigilant, and always expected something bad to happen. They felt that their defenses had been broken down and experienced great vulnerability. They felt they were held responsible for the violence. In adolescence: experienced a broken self-image and a variety of physical and mental problems. In adulthood: All have struggled with problems in the lower abdomen, unexplained pain, miscarriage, ectopic pregnancies, multiple inflammation, and problems that often ended in hysterectomy. All of them have struggled with sleeping problems and various physical problems such as fibro- myalgia, high blood pressure, dizziness, endocrine problems, diabetes, lymphatic problems, nervous system problems, asthma, epilepsy and eating disorders (especially obesity). |

| 6. Sigurdardottir, S.; Halldors-dottir, S. Screaming body and silent healthcare providers: A case study with a childhood sexual abuse (CSA) survivor [28]. | Consequences of the violence against one woman: This was a case study. Since childhood, she has experienced complex and far-reaching physical and health consequences such as recurrent abdominal pain, widespread and chronic pain, sleeping problems, indigestion, chronic back pain, fibromyalgia, musculoskeletal problems, recurrent urinary tract infections, irregular periods, ovarian cysts, ectopic pregnancies, endometrial hyperplasia, inflammation of the ovaries, uterine problems, and ovarian cancer. She told health professionals about her experience of sexual violence to increase their understanding of her health problems, but they remained silent and were unable to provide her with trauma-informed healthcare. |

| 7. Sigurdardottir, S.; Halldors-dottir, S.; Bender, S.S.; Agnarsdottir, G. Personal resurrection: Female childhood sexual abuse survivors’ experience of the Wellness-Program [29]. | Searching for internal healing of the consequences of sexual violence: The Wellness Program (Gæfusporin) was designed to promote the inner healing of women who had experienced sexual violence. The program lasted for 10 weeks with an organized program of 20 hours per week. A group of healthcare professionals used a holistic approach and provided holistic therapy individually, as well as group therapy, with an emphasis on the unity of body, mind, and soul. In their own view the most useful treatments for the women were as follows: group therapy where the emphasis was on sharing their experiences and gaining the support of other women who had experienced the same, as well as empowerment from supportive professionals; deep relaxation and hypnosis; body therapy with massage; trauma and stress education; craniosacral therapy; psychological group therapy with mindfulness; body therapy with an emphasis on dance; and body awareness therapy. |

| Concepts | Definition |

|---|---|

| A woman or a girl who is a victim of sexual violence | A woman or a girl who has been sexually assaulted is an individual who is part of a family and a community. The violence has made her more sensitive than usual to stress and she needs trauma-informed healthcare and trauma-informed therapy. She is now more vulnerable to various forms of violence. |

| Health | Health has many dimensions, including physical, mental, emotional, social, and societal. A woman’s health can be enhanced or weakened in various ways. A woman’s subjective health consists of her conceptual understanding of her own strengths, which enables her to achieve her most important goals regarding long-term happiness and well-being. Sexual violence has a significant negative impact on every dimension of health of the victim. |

| The environment | A woman’s and a girl’s environment can be divided into two dimensions: the inner, which includes the woman’s/girl’s needs, expectations, past experiences and her own self-image; and the external, which includes factors outside the woman and the girl that affect her, her family, friends and community. Sexual violence is a very destructive environmental factor that creates a toxic environment for the victim. |

| Empowering a woman or a girl who has been sexually assaulted | A woman’s and a girl’s subjective feelings about being empowered. Self-empowerment reduces a woman’s and a girl’s vulnerability in her situation, increases her well-being, gives her a stronger “voice” in her situation and a greater sense of control of her situation. Empowerment enables her to strengthen herself and cope better with the situation she is in. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sigurdardottir, S.; Halldorsdottir, S. Persistent Suffering: The Serious Consequences of Sexual Violence against Women and Girls, Their Search for Inner Healing and the Significance of the #MeToo Movement. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1849. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18041849

Sigurdardottir S, Halldorsdottir S. Persistent Suffering: The Serious Consequences of Sexual Violence against Women and Girls, Their Search for Inner Healing and the Significance of the #MeToo Movement. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(4):1849. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18041849

Chicago/Turabian StyleSigurdardottir, Sigrun, and Sigridur Halldorsdottir. 2021. "Persistent Suffering: The Serious Consequences of Sexual Violence against Women and Girls, Their Search for Inner Healing and the Significance of the #MeToo Movement" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 4: 1849. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18041849

APA StyleSigurdardottir, S., & Halldorsdottir, S. (2021). Persistent Suffering: The Serious Consequences of Sexual Violence against Women and Girls, Their Search for Inner Healing and the Significance of the #MeToo Movement. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(4), 1849. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18041849