Food Safety When Eating Out—Perspectives of Young Adult Consumers in Poland and Turkey—A Pilot Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection

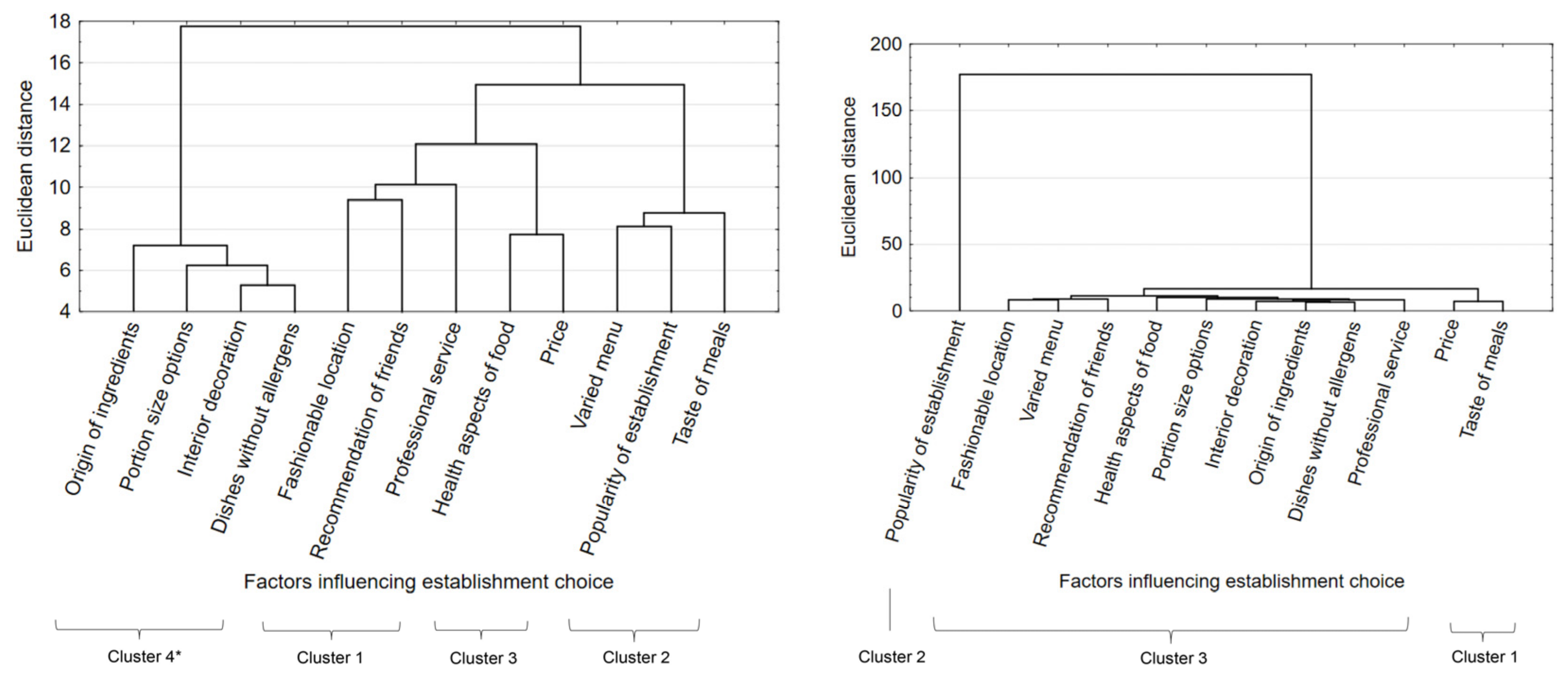

2.2. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic Characteristics and Overall Assessment

3.2. Consumer Experience and Practice Regarding Meals of Inadequate Health Quality

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lachat, C.; Nago, E.; Verstraeten, R.; Roberfroid, D.; Van Camp, J.; Kolsteren, P. Eating out of home and its association with dietary intake: A systematic review of the evidence. Obes. Rev. 2012, 13, 329–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, J.S.A. The foodservice industry: Eating out is more than just a meal. Food Qual. Prefer. 2013, 27, 223–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, J.; Goffe, L.; Brown, T.; Lake, A.A.; Summerbell, C.; White, M.; Wrieden, W.; Adamson, A.J. Frequency and socio-demographic correlates of eating meals out and take-away meals at home: Cross-sectional analysis of the UK national diet and nutrition survey, waves 1–4 (2008-12). Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2015, 12, 12–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Naidoo, N.; van Dam, R.M.; Ng, S.; Tan, S.C.; Chen, S.; Lim, J.Y.; Chan, M.F.; Chew, L.; Rebello, S.A. Determinants of eating at local and western fast-food venues in an urban Asian population: A mixed methods approach. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2017, 14, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, S.; Adams, J.; Wrieden, W.; White, M.; Brown, H. Sociodemographic characteristics and frequency of consuming home-cooked meals and meals from out-of-home sources: Crosssectional analysis of a population-based cohort study. Public Health Nutr. 2018, 12, 2255–2266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lund, T.B.; Kjærnesb, U. Eating out in four Nordic countries: National patterns and social stratification. Appetite 2017, 119, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, A.; Worosz, M.R.; Todd, E.C.D. Dining for Safety: Consumer Perceptions of Food Safety and Eating Out. J. Hospit. Tour. Res. 2009, 33, 471–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomaszewska, M.; Trafialek, J.; Suebpongsang, P.; Kolanowski, W. Food hygiene knowledge and practice of consumers in Poland and in Thailand—A survey. Food Cont. 2018, 85, 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auty, S. Consumer choice and segmentation in the restaurant industry. Serv. Ind. J. 2006, 12, 324–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Njite, D.; Dunn, G.; Kim, L.H. Beyond good food: What other attributes influence consumer preference and selection of fine dining restaurants? J. Foodserv. Bus. Res. 2008, 11, 237–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, J.; Nath, T. Factors affecting consumers’ eating-out choices in India: Implications for the restaurant industry. J. Foodserv. Bus. Res. 2013, 16, 197–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso, A.D.; O’Neill, M.; Liu, Y.; O’Shea, M. Factors driving consumer restaurant choice: An exploratory study from the southeastern united states. J. Hospit. Market. Manag. 2013, 22, 547–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, J.; Park, K.; Park, J. Which restaurant should I choose? Herd behavior in the restaurant industry. J. Foodserv. Bus. Res. 2016, 19, 396–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrington, R.J.; Fauser, S.G.; Ottenbacher, M.C.; Krause, A. Key information sources impacting Michelin restaurant choice. J. Foodserv. Bus. Res. 2016, 16, 219–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Heung, V.C.S. American theme restaurants: A study of consumer’s perceptions of the important attributes in restaurant selection. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2002, 7, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, K.H. Selection attributes and satisfaction of ethnic restaurant customers: A case of Korean restaurants in Australia. Int. J. Tour. Sci. 2016, 16, 151–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatimah, U.Z.; Boo, H.C.; Sambasivan, M.; Salleh, R. Foodservice hygiene factors—The consumer perspective. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2011, 30, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cullen, F. Factors influencing restaurant selection in Dublin. J. Foodserv. Bus. Res. 2005, 7, 53–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mottaleb, K.A.; Rahut, D.B.; Mishra, A.K. Consumption of food away from home in Bangladesh: Do rich households spend more? Appetite 2017, 119, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, L.; Wang, M.; Yang, Y.; Gong, S. Food safety in restaurants: The consumer perspective. Int. J. Hospit. Manag. 2019, 77, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolanowski, W.; Trafialek, J.; Drosinos, E.H.; Tzamalis, P. Polish and Greek young adults’ experience of low quality meals when eating out. Food Cont. 2020, 109, 106901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ljubičić, M.; Matek Sarić, M.; Colić Barić, I.; Rumbak, I.; Komes, D.; Šatalić, Z.; Guiné, R.P.F. Consumer knowledge and attitudes toward healthy eating in Croatia: A cross-sectional study. Archiv. Indust. Hyg. Toxicol. 2017, 68, 153–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Andrade, G.C.; da Costa Louzada, L.M.; Azeredo, C.M.; Ricardo, C.Z.; Bortolleto Martins, A.P.; Levy, R.B. Out-of-home food consumers in Brazil: What do they eat? Nutrients 2018, 10, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hu, P.; Wu, T.; Zhang, F.; Zhang, Y.; Lu, L.; Zeng, H.; Shi, Z.; Sharma, M.; Xun, L.; Zhao, Y. Association between eating out and socio-demographic factors of university students in Chongqing, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kim, R.B. Determinants of brand equity for credence goods: Consumers’ preference for country origin, perceived value and food safety. Agric. Econom. 2012, 58, 299–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Trafialek, J.; Lehrke, M.; Lücke, F.K.; Kołożyn-Krajewska, D.; Janssen, J. HACCP-based procedures in Germany and Poland. Food Cont. 2015, 55, 66–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, C.; Garg, V.; Kapoor, D.; Wasser, H.; Prabhakaran, D.; Jaacks, L.M. Food Choice Drivers in the Context of the Nutrition Transition in Delhi, India. J. Nutr. Edu. Behav. 2018, 50, 675–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trafialek, J.; Kołożyn-Krajewska, D. Implementation of Safety Assurance System in Food Production in Poland. Pol. J. Food Nutr. Sci. 2011, 61, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McNeil, P.; Young, C.P. Customer satisfaction in gourmet food trucks: Exploring attributes and their relationship with customer satisfaction. J. Foodserv. Bus. Res. 2019, 22, 326–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djekic, I.; Jankovic, D.; Rajkovic, A. Analysis of foreign bodies present in European food using data from Rapid Alert System for Food and Fed (RASFF). Food Cont. 2017, 79, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trafialek, J.; Kaczmarek, S.; Kolanowski, W. The risk analysis of metallic foreign bodies in food products. J. Food Qual. 2016, 39, 398–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worsfold, D. Eating out: Consumer perceptions of food safety. Int. J. Environ. Health Res. 2016, 16, 219–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. RASF—The Rapid Alert System for Food and Feed. 2019 Annual Report; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2020; Available online: https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/2c5c7729-0c31-11eb-bc07-01aa75ed71a1/language-en/format-PDF/source-174742448 (accessed on 20 January 2021).

- Lemos, G.J.; Valle Garcia, M.; de Oliveira Mello, R.; Venturini Copetti, M. Consumers complaints about moldy foods in a Brazilian website. Food Cont. 2018, 92, 380–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, E.J.; Knechtges, P.L. Food safety knowledge and practices of young adults. J. Environ. Health 2015, 77, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Marklinder, I.; Ahlgren, R.; Blücher, A.; Börjesson, S.M.E.; Hellkvist, F.; Moazzami, M.; Schelin, J.; Zetterström, E.; Eskhult, G.; Danielsson-Tham, M.L. Food safety knowledge, sources thereof and self-reported behaviour among university students in Sweden. Food Cont. 2020, 113, 107–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahandideh, B.; Golmohammadi, A.; Meng, F.; O’Gorman, K.D. Cross-cultural comparison of Chinese and Arab consumer complaint behavior in the hotel context. Int. J. Hospit. Manag. 2014, 41, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguiar, R.S.; Esmerino, E.; Rocha, R.S.; Pimentel, T.C.; Cruz, A.G. Physical hazards in dairy products: Incidence in a consumer complaint website in Brazil. Food Cont. 2019, 86, 66–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lueckl, J.; Weyermair, K.; Matt, M.; Manner, K.; Fuchs, K. Results of official food control in Austria 2010–2016. Food Cont. 2019, 99, 190–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marras, S.R. Comparative analysis of legislative approaches to street food in South American metropolises. In Street Food. Culture, Economy, Health and Governance; Cardoso, R., Companion, M., Marras, S., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2014; pp. 15–45. [Google Scholar]

- Trafialek, J.; Czarniecka-Skubina, E.; Kulaitiené, J.; Vaitkeviciene, N. Restaurant’s Multidimensional Evaluation Concerning Food Quality, Service, and Sustainable Practices: A Cross-National Case Study of Poland and Lithuania. Sustainability 2020, 12, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Okumus, B.; Sönmez, S.; Moore, S.; Auvil, D.P.; Parks, G.D. Exploring safety of food truck products in a developed country. Int. J. Hospit. Manag. 2019, 81, 150–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No. | Question/Options of the Answer | |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | How often do you eat out?—Mark one answer in each column. | |

| On weekdays (from Monday till Friday) | At the weekend | |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

| 2. | What is most important to you when choosing a place to eat out at?—You can mark several answers. | |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

| ||

| 3. | How often have you been served a poor the quality of your meal been poor?—Mark one answer. | |

|

| |

|

| |

| 4. | How often do you complain when the quality of your meal has been poor?—Mark one answer. | |

|

| |

|

| |

| 5. | What kind of quality problems do you find the most often in meals you have bought, if any?—You can mark several answers | |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

| Factors | Variants | Poland (%) | Turkey (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 18–24 years old | 51.5 | 55.0 |

| 25–30 | 48.5 | 45.0 | |

| Sex | Female | 50.0 | 50.0 |

| Male | 50.0 | 50.0 | |

| Education | Secondary | 45.5 | 21.5 |

| Higher | 54.5 | 78.5 | |

| Marital/Family Status | Single | 49.0 | 62.0 |

| Family up to 4 persons | 32.5 | 34.0 | |

| Family above 4 persons | 18.5 | 4.0 | |

| Employment (currently) | Yes | 64.5 | 70.0 |

| No | 35.5 | 30.0 | |

| Place of Origin | Small town or village | 30.0 | 4.0 |

| Medium city | 28.0 | 44.0 | |

| Big city | 42.0 | 52.0 | |

| Co-Residents in Household | Living alone | 28.0 | 38.5 |

| With a partner | 26.5 | 14.0 | |

| With family/friends up to 4 persons | 24.5 | 30.5 | |

| With family/friends above 4 persons | 21.0 | 11.5 |

| Frequency of Eating Out from Monday to Friday | Poland (%) | Turkey (%) | Student’s t-Test p-Value | Frequency of Eating Out at the Weekend | Poland (%) | Turkey (%) | Student’s t-Test p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| hardly ever | 16.5 | 22.0 | ns * | hardly ever | 13.0 | 14.0 | ns * |

| once | 32.0 | 24.0 | ns * | sometimes | 23.5 | 40.0 | 0.000 |

| twice | 36.5 | 26.0 | 0.030 | once | 33.5 | 19.0 | 0.000 |

| more than 3 times | 15.5 | 19.0 | ns * | twice | 28.0 | 18.0 | 0.017 |

| every day | 0.0 | 9.5 | 0.000 | more than 3 times | 2.0 | 8.0 | 0.005 |

| Poor-Quality Meals Experience | Being Served a Poor-Quality Meal (Question 3) | Complaining When Served a Poor-Quality Meal (Question 4) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Poland (%) | Turkey (%) | T Student p-Value | Poland (%) | Turkey (%) | T Student p-Value | |

| Very often | 0.0 | 4.0 | 0.002 | 11.0 | 31.5 | 0.000 |

| Hardly ever | 28.0 | 23.0 | ns * | 43.0 | 24.0 | 0.000 |

| From time to time | 48.0 | 44.5 | ns * | 42.5 | 40.0 | ns * |

| Never | 24.0 | 28.0 | ns * | 3.5 | 4.0 | ns * |

| Kind of Problem | Poland (%) | Turkey (%) | Student’s t-Test p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Finding insects | 5.0 | 0.0 | 0.001 |

| Finding glass foreign objects | 3.0 | 0.0 | 0.013 |

| Finding plastic foreign objects | 4.0 | 0.0 | 0.000 |

| Finding natural foreign objects | 40.0 | 52.5 | 0.012 |

| Temperature of hot meal | 19.5 | 35.5 | 0.000 |

| Strange taste | 5.0 | 78.5 | 0.000 |

| Finding molds | 5.0 | 34.5 | 0.000 |

| Abdominal pain after a meal | 22.0 | 31.5 | 0.031 |

| Kind of Quality Problems | Country | Education (%) | Age (%) | Sex (%) | Marital Status (%) | Employment (%) | Place of Origin (%) | Inhabitation (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Finding natural foreign objects | Poland | ns * | ns * | p = 0.000 F 27.5 M 72.5 | p = 0.000 S 48.3 F4 28.5 Fa4 23.2 | ns * | p = 0.000 S 34.0 M 21.4 B 44.6 | p = 0.000 A 28.5 B 32.3 C 16.0 D 23.2.0 |

| Turkey | ns * | ns * | ns * | ns * | ns * | ns * | ns * | |

| Inadequate temperature of hot meal | Poland | ns * | ns * | p = 0.001 F 71.8 M 28.2 | p = 0.001 S 36.0 F4 56.4 Fa4 7.6 | p = 0.020 E 79.5 nE 20.5 | ns * | ns * |

| Turkey | ns * | ns * | ns * | ns * | ns * | ns * | ns * | |

| Finding insects | Poland | p = 0.020 S 10.0 H 90.0 | ns * | p = 0.048 F 80.0 M 20.0 | p = 0.020 S 90.0 F4 0.0 Fa4 10.0 | ns * | ns * | ns * |

| Turkey | ** | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Strange taste | Poland | p = 0.002 S 0.0 H 100 | ns * | ns * | ns * | ns * | ns * | ns * |

| Turkey | ns * | ns * | ns * | p = 0.021 S 66.3 F4 31.2 Fa4 2.5 | ns * | 0.003 S 7.0 M 38.8 B 54.2 | ns * | |

| Finding molds | Poland | ns * | ns * | ns * | ns * | ns * | ns * | ns * |

| Turkey | p = 0.013 S 11.6 H 88.4 | ns * | ns * | ns * | ns * | ns * | ns * | |

| Abdominal pain after a meal | Poland | ns * | p = 0.012 A 68.2 B 31.8 | ns * | ns * | ns * | p = 0.006 S 47.8 M 13.6 B 38.6 | ns * |

| Turkey | ns * | ns * | ns * | ns * | ns * | ns * | ns * | |

| Finding glass foreign objects | Poland | p = 0.023 S 0.0 H 100.0 | ns * | ns * | p = 0.034 S 100.0 F4 0.0 Fa4 0.0 | ns * | p = 0.014 S 0.0 M 0.0 B 100.0 | ns * |

| Turkey | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Finding plastic foreign objects | Poland | ns * | ns * | ns * | ns * | ns * | ns * | ns * |

| Turkey | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kolanowski, W.; Karaman, A.D.; Yildiz Akgul, F.; Ługowska, K.; Trafialek, J. Food Safety When Eating Out—Perspectives of Young Adult Consumers in Poland and Turkey—A Pilot Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1884. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18041884

Kolanowski W, Karaman AD, Yildiz Akgul F, Ługowska K, Trafialek J. Food Safety When Eating Out—Perspectives of Young Adult Consumers in Poland and Turkey—A Pilot Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(4):1884. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18041884

Chicago/Turabian StyleKolanowski, Wojciech, Ayse Demet Karaman, Filiz Yildiz Akgul, Katarzyna Ługowska, and Joanna Trafialek. 2021. "Food Safety When Eating Out—Perspectives of Young Adult Consumers in Poland and Turkey—A Pilot Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 4: 1884. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18041884