The Association between Assisted Reproduction Technology (ART) and Social Perception of Childbearing Deadline Ages: A Cross-Country Examination of Selected EU Countries

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Data and Methods

2.1. Data

2.1.1. Individual-Level Data

2.1.2. Country-Level Data

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Dependent Variables

2.2.2. Independent Variables

2.2.3. Control Variables

2.3. Modeling

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Results

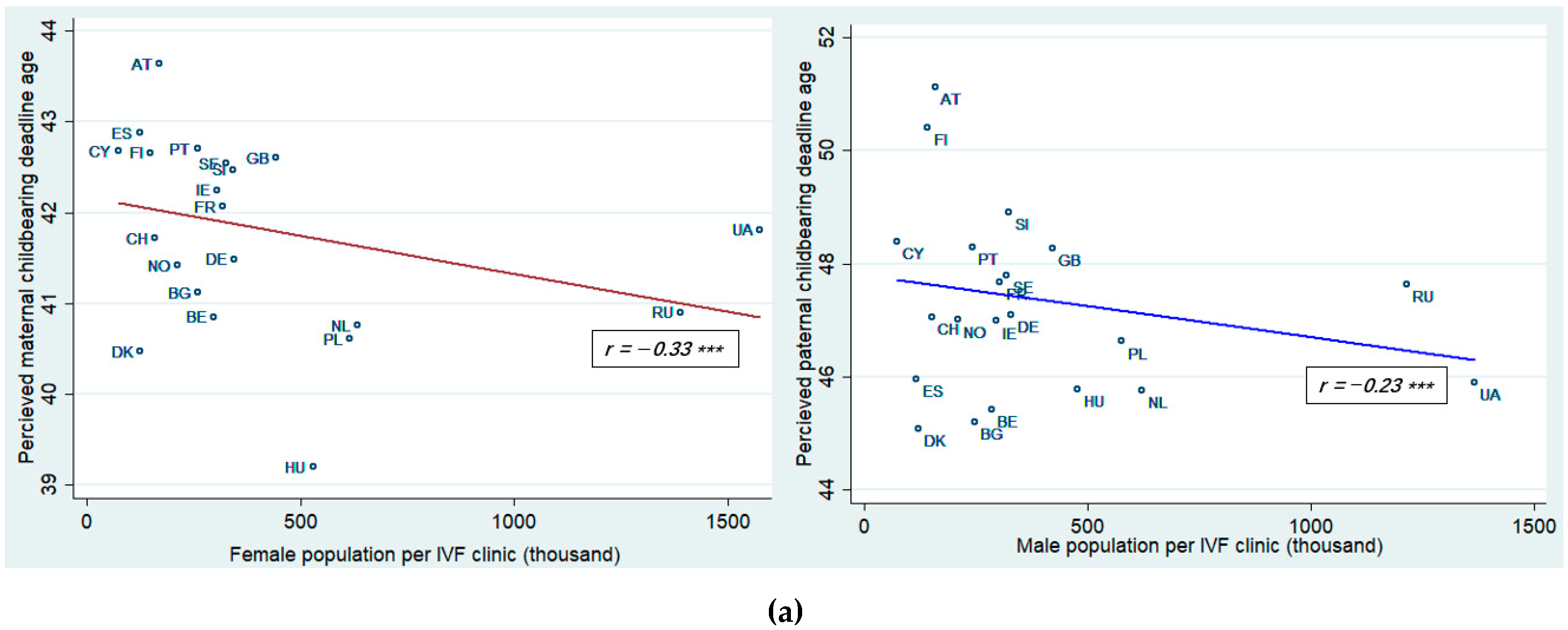

3.2. Bivariate Results

3.3. Multivariate Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations

4.2. Implications

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Country | ESS Data (25 Countries) | Number of IVF Clinics Data (21 Countries) | ART Cycles Data (13 Countries) | ART Infants Data (12 Countries) |

| Austria | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Belgium | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Denmark | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Finland | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| France | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Germany | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Netherlands | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Norway | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Slovenia | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Sweden | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Switzerland | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| UK | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Cyprus | √ | √ | √ | |

| Bulgaria | √ | √ | ||

| Hungary | √ | √ | ||

| Ireland | √ | √ | ||

| Poland | √ | √ | ||

| Portugal | √ | √ | ||

| Russia | √ | √ | ||

| Spain | √ | √ | ||

| Ukraine | √ | √ | ||

| Estonia | √ | |||

| Latvia | √ | |||

| Romania | √ | |||

| Slovakia | √ |

Appendix B

| Country | Abbreviation |

| Austria | AT |

| Belgium | BE |

| Bulgaria | BG |

| Cyprus | CY |

| Denmark | DK |

| Finland | FI |

| France | FR |

| Germany | DE |

| Hungary | HU |

| Ireland | IE |

| Netherlands | NL |

| Norway | NO |

| Poland | PL |

| Portugal | PT |

| Russia | RU |

| Slovenia | SI |

| Spain | ES |

| Sweden | SE |

| Switzerland | CH |

| UK | GB |

| Ukraine | UA |

References

- Kohler, H.-P.; Billari, F.C.; Ortega, J.A. The Emergence of Lowest-Low Fertility in Europe during the 1990s. Popul. Dev. Rev. 2002, 28, 641–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohler, H.-P.; Billari, F.C.; Ortega, J.A. Low Fertility in Europe: Causes, Implications and Policy Options. In The Baby Bust: Who Will Do the Work? who Will Pay the Taxes? Harris, F.R., Ed.; Rowman & Littlefield Publishers: Lanham, MD, USA, 2006; pp. 48–109. [Google Scholar]

- Prioux, F. Late fertility in Europe: Some comparative and historical data. Rev. d’Épidémiologie Santé Publique 2005, 53, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Albis, H.; Greulich, A.; Ponthière, G. Education, labour, and the demographic consequences of birth postponement in Europe. Demogr. Res. 2017, 36, 691–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nathan, M.; Pardo, I. Fertility Postponement and Regional Patterns of Dispersion in Age at First Birth: Descriptive Findings and Interpretations. Comp. Popul. Stud. 2019, 44, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aassve, A.; Billari, F.C.; Spéder, Z. Societal Transition, Policy Changes and Family Formation: Evidence from Hungary. Eur. J. Popul. 2006, 22, 127–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McQuillan, J.; Greil, A.L.; Shreffler, K.M.; Wonch-Hill, P.A.; Gentzler, K.C.; Hathcoat, J.D. Does the Reason Matter? Variations in Childlessness Concerns Among, U.S. Women. J. Marriage Fam. 2012, 74, 1166–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dykstra, P.A.; Hagestad, G.O. How demographic patterns and social policies shape interdependence among lives in the family realm. Popul. Horizons 2016, 13, 54–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Spéder, Z.; Kapitány, B. Influences on the Link Between Fertility Intentions and Behavioural Outcomes. In Reproductive Decision-Making in a Macro-Micro Perspective; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 79–112. [Google Scholar]

- Hodkinson, P. Family and parenthood in an ageing ‘youth’culture: A collective embrace of dominant adulthood? Sociology 2013, 47, 1072–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Braithwaite, D.; Olson, L.; Golish, T.; Soukup, C.; Turman, P. “Becoming a family”: Developmental processes represented in blended family discourse. J. Appl. Commun. Res. 2001, 29, 221–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Billari, F.C.; Liefbroer, A.C.; Philipov, D. The Postponement of Childbearing in Europe: Driving Forces and Implications. Vienna Yearb. Popul. Res. 2008, 2006, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billari, F.C.; Goisis, A.; Liefbroer, A.C.; Settersten, R.A.; Aassve, A.; Hagestad, G.; Speder, Z. Social age deadlines for the childbearing of women and men. Hum. Reprod. 2010, 26, 616–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Billari, F.C.; Kohler, H.-P.; Andersson, G.; Lundström, H. Approaching the limit: Long-term trends in late and very late fertility. Popul. Dev. Rev. 2007, 33, 149–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billari, F.C.; Philipov, D.; Testa, M.R. Attitudes, Norms and Perceived Behavioural Control: Explaining Fertility Intentions in Bulgaria. Eur. J. Popul. 2009, 25, 439–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Buchmann, M.C.; Kriesi, I. Transition to Adulthood in Europe. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2011, 37, 481–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, L.H. Infertility as Boundary Ambiguity: One Theoretical Perspective. Fam. Process. 1987, 26, 359–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Büchler, A.; Parizer, K. Maternal Age in the Regulation of Reproductive Medicine—A Comparative Study. Int. J. Law Policy Fam. 2017, 31, 269–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, L.J. Pushing for the perfect time: Social and biological fertility. Women’s Stud. Int. Forum 2017, 62, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greil, A.; McQuillan, J.; Slauson-Blevins, K. The social construction of infertility. Sociol. Compass 2011, 5, 736–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Loftus, J.; Andriot, A.L. “That’s What Makes a Woman”: Infertility and Coping with a Failed Life Course Transition. Sociol. Spectr. 2012, 32, 226–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greil, A.L. Infertile Bodies: Medicalization, Metaphor, and Agency. In Infertility around the Globe: New Thinking on Childlessness, Gender, and Reproductive Technologies: A View from the Social Sciences; Inhorn, M.C., van Balen, F., Eds.; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2002; pp. 101–118. [Google Scholar]

- Haug, S.; Milewski, N. Women’s Attitudes toward Assisted Reproductive Technologies—A Pilot Study among Migrant Minorities and Non-migrants in Germany. Comp. Popul. Stud. 2019, 43, 343–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szalma, I.; Djundeva, M. What shapes public attitudes towards assisted reproduction technologies in Europe? Demográfia Engl. Ed. 2020, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniluk, J.C.; Koert, E.; Cheung, A. Childless women’s knowledge of fertility and assisted human reproduction: Identifying the gaps. Fertil. Steril. 2012, 97, 420–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniluk, J.C.; Koert, E. The other side of the fertility coin: A comparison of childless men’s and women’s knowledge of fertility and assisted reproductive technology. Fertil. Steril. 2013, 99, 839–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heikkilä, K.; Länsimies, E.; Hippeläinen, M.; Heinonen, S. Assessment of attitudes towards assisted reproduction: A survey among medical students and parous women. Gynecol. Endocrinol. 2006, 22, 613–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Präg, P.; Mills, M.C. Assisted reproductive technology in Europe: Usage and regulation in the context of cross-border repro-ductive care. In Childlessness in Europe: Contexts, Causes, and Consequences; Kreyenfeld, M., Konientzka, D., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 289–309. [Google Scholar]

- Data and Documentation by Round|European Social Survey (ESS). Available online: https://www.europeansocialsurvey.org/data/download.html?r=3. (accessed on 22 February 2020).

- de Mouzon, J.; Goossens, V.; Bhattacharya, S.; Castilla, J.A.; Ferraretti, A.P.; Korsak, V.; Kupka, M.; Nygren, K.G.; Andersen, A.N. Assisted reproductive technology in Europe, 2006: Results generated from European registers by ESHRE. Hum. Reprod. 2010, 25, 1851–1862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GDP per Capita (Constant 2010 US$)|Data. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.KD. (accessed on 22 February 2020).

- Labor Force Participation Rate, Female (% of Female Population ages 15–64) (Modeled ILO Estimate)|Data. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SL.TLF.ACTI.FE.ZS?view=chart (accessed on 22 February 2020).

- Social Protection Statistics—Family and Children Benefits—Statistics Explained. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Social_protection_statistics_-_family_and_children_benefits&oldid=427822 (accessed on 22 February 2020).

- UNESCO Institute for Statistics. International Standard Classification of Education ISCED 1997; UNESCO-UIS: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Wooldridge, J.M. Introductory Econometrics: A Modern Approach, 5th ed.; Nelson Education: Mason, OH, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Panda, S.R.; Sachan, S.; Hota, S. A Systematic Review Evaluating the Efficacy of Intra-Ovarian Infusion of Autologous Platelet-Rich Plasma in Patients with Poor Ovarian Reserve or Ovarian Insufficiency. Cureus 2020, 12, 12037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pribenszky, C.; Anna-Maria, N.; Markus, M. Time-lapse culture with morphokinetic embryo selection improves pregnancy and live birth chances and reduces early pregnancy loss: A meta-analysis. Reprod. Biomed. Online 2017, 35, 511–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zemyarska, M.S. Is it ethical to provide IVF add-ons when there is no evidence of a benefit if the patient requests it? J. Med. Ethics 2019, 45, 346–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salama, M.; Isachenko, V.; Isachenko, E.; Rahimi, G.; Mallmann, P.; Westphal, L.M.; Inhorn, M.C.; Patrizio, P. Cross border reproductive care (CBRC): A growing global phenomenon with multidimensional implications (a systematic and critical review). J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2018, 35, 1277–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hudson, N.; Culley, L.; Blyth, E.; Norton, W.; Rapport, F.; Pacey, A. Cross-border reproductive care: A review of the literature. Reprod. Biomed. Online 2011, 22, 673–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gromski, P.S.; Smith, A.D.; Lawlor, D.A.; Sharara, F.I.; Nelson, S.M. 2008 financial crisis vs 2020 economic fallout: How COVID-19 might influence fertility treatment and live births. medRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferraretti, A.; Nygren, K.; Andersen, A.N.; De Mouzon, J.; Kupka, M.; Calhaz-Jorge, C.; Wyns, C.; Gianaroli, L.; Goossens, V. Trends over 15 years in ART in Europe: An analysis of 6 million cycles†. Hum. Reprod. Open 2017, 2017, hox012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fauser, B.C.J.M.; Boivin, J.; Barri, P.N.; Tarlatzis, B.C.; Schmidt, L.; Levy-Toledano, R. Beliefs, attitudes and funding of assisted reproductive technology: Public perception of over 6,000 respondents from 6 European countries. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0211150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inhorn, M.C. Global infertility and the globalization of new reproductive technologies: Illustrations from Egypt. Soc. Sci. Med. 2003, 56, 1837–1851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramowitz, J. Assisted Reproductive Technology and Women’s Timing of Marriage and Childbearing. J. Fam. Econ. Issues 2017, 38, 100–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Katwijk, C.; Peeters, L. Clinical aspects of pregnancy after the age of 35 years: A review of the literature. Hum. Reprod. Update 1998, 4, 185–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lambert, S.M.; Masson, P.; Fisch, H. The male biological clock. World J. Urol. 2006, 24, 611–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, B.H.; Legato, M.; Fisch, H. Medical Implications of the Male Biological Clock. JAMA 2006, 296, 2369–2371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de La Rochebrochard, E.; de Mouzon, J.; The´pot, F.; Thonneau, P. Fathers over 40 and increased failure to conceive: The lessons of in vitro fertilization in France. Fertil. Steril. 2006, 85, 1420–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Throsby, K.; Gill, R. It’s Different for Men. Men Masc. 2004, 6, 330–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Verhaak, C.M.; Smeenk, J.M.J.; Evers, A.W.M.; Kremer, J.A.M.; Kraaimaat, F.W.; Braat, D.D.M. Women’s emotional adjustment to IVF: A systematic review of 25 years of research. Hum. Reprod. Updat. 2006, 13, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Greil, A.L. Infertility and psychological distress: A critical review of the literature. Soc. Sci. Med. 1997, 45, 1679–1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gameiro, S.; Boivin, J.; Peronace, L.; Verhaak, C. Why do patients discontinue fertility treatment? A systematic review of reasons and predictors of discontinuation in fertility treatment. Hum. Reprod. Updat. 2012, 18, 652–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peterson, B.; Newton, C.; Rosen, K.; Skaggs, G. Gender differences in how men and women who are referred for IVF cope with infertility stress. Hum. Reprod. 2006, 21, 2443–2449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sobotka, T.; Billari, F.C.; Kohler, H.-P. The Return of Late Childbearing in Developed Countries: Causes, Trends and Implications; Vienna Institute of Demography: Vienna, Austria, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Benzies, K.; Tough, S.; Tofflemire, K.; Frick, C.; Faber, A.; Newburn-Cook, C. Factors Influencing Women’s Decisions About Timing of Motherhood. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Neonatal Nurs. 2006, 35, 625–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalmijn, M.; Kraaykamp, G. Late or later? A sibling analysis of the effect of maternal age on children’s schooling. Soc. Sci. Res. 2005, 34, 634–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Finley, G.E. Parental Age and Parenting Quality as Perceived by Late Adolescents. J. Genet. Psychol. 1998, 159, 505–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mortimer, J.T.; Moen, P. The changing social construction of age and the life course: Precarious identity and enactment of “early” and “encore” Stages of Adulthood. In Handbook of the Life Course; Shanahan, M., Mortimer, J., Johnson, M., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; pp. 111–129. [Google Scholar]

- Bobic, M. Transition to parenthood: New insights into socio-psychological costs of childbearing. Stanovništvo 2018, 56, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sobotka, T. Post-transitional fertility: The role of childbearing postponement in fuelling the shift to low and unstable fertility levels. J. Biosoc. Sci. 2017, 49, S20–S45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kausar, S.; Bewley, S. Pregnancy after the Age of 40. Women’s Health 2006, 2, 839–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Simchen, M.J.; Yinon, Y.; Moran, O.; Schiff, E.; Sivan, E. Pregnancy Outcome After Age 50. Obstet. Gynecol. 2006, 108, 1084–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

| Respondents’ Demographic Characteristics | Mean (SE) | |

|---|---|---|

| Maternal Childbearing Deadline Age | Paternal Childbearing Deadline Age | |

| Age-group | ||

| 15–24 | 42.3 (0.16) | 46.6 (0.18) |

| 25–34 | 42.2 (0.13) | 47.1 (0.17) |

| 35–44 | 42.3 (0.10) | 47.8 (0.19) |

| 45–54 | 41.7 (0.10) | 47.4 (0.17) |

| 55–64 | 41.2 (0.10) | 47.7 (0.18) |

| 65 + | 41.2 (0.09) | 47.4 (0.15) |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 41.7 (0.06) | 47.5 (0.09) |

| Male | 41.9 (0.07) | 47.1 (0.11) |

| Health | ||

| Good or Very Good | 42.1 (0.06) | 47.5 (0.08) |

| Fair | 41.3 (0.08) | 47.1 (0.15) |

| Bad or Very Bad | 41.2 (0.15) | 46.7 (0.25) |

| Marital Status | ||

| Married or Civil partnership | 41.6 (0.06) | 47.2 (0.09) |

| Single and not in civil partnership (including divorced, separated, widowed) | 42.1 (0.07) | 47.5 (0.10) |

| Educational Attainment Completed | ||

| Less than lower secondary (ISCED 0–1) | 41.7 (0.12) | 47.1 (0.21) |

| Lower secondary completed (ISCED 2) | 41.7 (0.11) | 46.5 (0.16) |

| Upper secondary completed (ISCED 3) | 41.6 (0.07) | 47.3 (0.11) |

| Higher than post-secondary completed (ISCED 4–6) | 42.2 (0.08) | 48.1 (0.13) |

| Number of Children | ||

| None | 42.4 (0.09) | 47.5 (0.12) |

| 1 | 41.7 (0.10) | 47.2 (0.16) |

| 2 | 41.4 (0.07) | 47.0 (0.12) |

| 3 or more | 41.6 (0.09) | 47.5 (0.16) |

| Residence | ||

| City | 41.9 (0.06) | 47.4 (0.09) |

| Rural or country | 41.8 (0.07) | 47.2 (0.11) |

| Religion | ||

| Do not belong to any religion | 41.9 (0.07) | 47.0 (0.11) |

| Roman Catholic | 41.9 (0.08) | 47.5 (0.12) |

| Protestant | 41.5 (0.10) | 47.7 (0.16) |

| Eastern Orthodox | 41.3 (0.22) | 46.7 (0.40) |

| Others | 41.4 (0.30) | 46.9 (0.46) |

| Subjective Household Income | ||

| Living comfortably | 42.1 (0.08) | 47.3 (0.11) |

| Coping | 41.8 (0.06) | 47.6 (0.10) |

| Difficult | 41.5 (0.10) | 46.9 (0.18) |

| Very Difficult | 41.6 (0.18) | 46.6 (0.30) |

| Country | Maternal Childbearing Deadline Age | Paternal Childbearing Deadline Age |

|---|---|---|

| Austria | 43.6 | 51.1 |

| Belgium | 40.9 | 45.4 |

| Bulgaria | 41.1 | 45.2 |

| Cyprus | 42.7 | 48.4 |

| Denmark | 40.5 | 45.1 |

| Finland | 42.7 | 50.4 |

| France | 42.2 | 47.7 |

| Germany | 41.5 | 47.1 |

| Hungary | 39.2 | 45.8 |

| Ireland | 42.3 | 47.0 |

| Netherlands | 40.8 | 45.8 |

| Norway | 41.4 | 47.0 |

| Poland | 40.6 | 46.6 |

| Portugal | 42.7 | 48.3 |

| Russia | 40.9 | 47.6 |

| Slovenia | 42.5 | 48.9 |

| Spain | 42.9 | 46.0 |

| Sweden | 42.5 | 47.8 |

| Switzerland | 41.7 | 47.1 |

| UK | 42.6 | 48.3 |

| Ukraine | 41.8 | 45.9 |

| Average | 41.8 | 47.3 |

| Country | Num.IVF Clinic | Female Pop. (1000) Per IVF Clinic | Male Pop. (1000) Per IVF Clinic | ART Cycles | Pop. (Million) | ART Cycles Per Pop. | ART Infants | National Births | % of ART Infants |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Austria | 25 | 170 | 160 | 5177 | 8.3 | 624 | 1041 | 78,227 | 1.3 |

| Belgium | 18 | 298 | 286 | 22,730 | 10.5 | 2165 | 4019 | 121,382 | 3.3 |

| Denmark | 22 | 125 | 122 | 12,618 | 5.4 | 2337 | 2674 | 65,647 | 4.1 |

| Finland | 18 | 149 | 143 | 9116 | 5.3 | 1720 | 1908 | 59,063 | 3.2 |

| France | 102 | 318 | 304 | 65,749 | 61.2 | 1074 | 13,480 | 829,000 | 1.6 |

| Germany | 122 | 345 | 330 | 54,695 | 82.4 | 664 | 10,427 | 675,144 | 1.5 |

| Netherlands | 13 | 634 | 623 | 17,770 | 16.4 | 1084 | 4448 | 185,913 | 2.4 |

| Norway | 11 | 213 | 209 | 7134 | 4.7 | 1518 | 1660 | 58,746 | 2.8 |

| Slovenia | 3 | 342 | 325 | 2807 | 2.0 | 1404 | 672 | 18,649 | 3.6 |

| Sweden | 14 | 327 | 320 | 14,931 | 9.1 | 1631 | 3417 | 104,495 | 3.3 |

| Switzerland | 24 | 159 | 152 | 7109 | 7.5 | 948 | 1241 | 73,771 | 1.7 |

| UK | 70 | 443 | 422 | 43,953 | 60.5 | 726 | 12,698 | 726,000 | 1.7 |

| Cyprus | 7 | 74 | 74 | 1432 | 1.0 | 1432 | |||

| Bulgaria | 15 | 260 | 248 | ||||||

| Hungary | 10 | 529 | 479 | ||||||

| Ireland | 7 | 306 | 297 | ||||||

| Poland | 32 | 615 | 577 | ||||||

| Portugal | 21 | 259 | 242 | ||||||

| Russia | 55 | 1389 | 1214 | ||||||

| Spain | 182 | 124 | 118 | ||||||

| Ukraine | 16 | 1573 | 1366 |

| Num. of Population Per IVF Clinic | ART Cycles/Population | % of ART Infants | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal Deadline Age | Paternal Deadline Age | Maternal Deadline Age | Paternal Deadline Age | Maternal Deadline Age | Paternal Deadline Age | |

| b (SE) | b (SE) | b (SE) | b (SE) | b (SE) | b (SE) | |

| Independent Variable | −3.16 × 10−3 (1.46 × 10−3) * | 3.17 × 10−3 (2.64 × 10−3) | −1.02 × 10−3 (4.48 × 10−4) * | −1.43 × 10−3 (8.76 × 10−5) | −0.48 (0.28) | −0.76 (0.54) |

| Age-group (ref: 15–24) | ||||||

| 25–34 | 0.01 (0.18) | 0.98 (0.28) *** | −0.23 (0.21) | 1.13 (0.32) *** | −0.23 (0.21) | 1.11 (0.32) ** |

| 35–44 | 0.43 (0.19) * | 2.68 (0.30) *** | 0.28 (0.22) | 2.87 (0.34) *** | 0.27 (0.21) | 2.86 (0.34) *** |

| 45–54 | −0.01 (0.19) | 2.77 (0.30) *** | −0.21 (0.22) | 3.17 (0.35) *** | −0.20 (0.22) | 3.16 (0.35) *** |

| 55–64 | −0.47 (0.20) * | 2.98 (0.31) *** | −0.68 (0.23) ** | 3.21 (0.36) *** | −0.68 (0.23) ** | 3.19 (0.36) *** |

| 65+ | −0.59 (0.19) ** | 2.92 (0.30) *** | −1.02 (0.23) *** | 3.20 (0.35) *** | −1.02 (0.22) *** | 3.19 (0.36) *** |

| Female | −0.14 (0.09) | 0.62 (0.14) *** | −0.06 (0.10) | 0.66 (0.16) *** | −0.05 (0.10) | 0.68 (0.16) *** |

| Married/Civil partnership | 0.06 (0.01) *** | 0.14 (0.02) *** | 0.05 (0.12) ** | 0.13 (0.19) *** | 0.05 (0.12) ** | 0.13 (0.03) *** |

| City residence | 0.03 (0.09) | 0.13 (0.14) | 0.09 (0.10) | 0.32 (0.17) | 0.09 (0.10) | 0.31 (0.17) |

| Religion (ref: no religion) | ||||||

| Catholic | 0.01 (0.12) | 0.34 (0.18) | −0.12 (0.14) | 0.20 (0.22) | −0.14 (0.14) | 0.20 (0.22) |

| Protestant | −0.05 (0.14) | 0.57 (0.21) ** | −4.54 × 10−4 (0.14) | 0.65 (0.22) ** | −0.01 (0.14) | 0.65 (0.22) ** |

| Orthodox | −0.41 (0.72) | −0.13 (1.19) | −0.24 (0.77) | −0.01 (1.25) | −0.25 (0.77) | −0.90 (1.25) |

| Others | −0.35 (0.25) | −0.01 (0.42) | −0.33 (0.27) | 0.21 (0.46) | −0.34 (0.27) | 0.21 (0.46) |

| Education (ref: < Lower secondary) | ||||||

| Lower secondary | 0.16 (0.16) | −0.15 (0.26) | 0.39 (0.21) | −0.09 (0.32) | 0.38 (0.21) | −0.10 (0.32) |

| Upper secondary | 0.04 (0.16) | 0.54 (0.25) * | 0.33 (0.19) | 0.64 (0.31) * | 0.32 (0.19) | 0.63 (0.31) * |

| Higher than post-secondary | 0.69 (0.17) *** | 1.73 (0.26) *** | 0.96 (0.20) *** | 1.88 (0.32) *** | 0.96 (0.20) *** | 1.87 (0.32) *** |

| Number of children (ref: none) | ||||||

| 1 | −0.20 (0.15) | −0.93 (0.24) *** | −0.16 (0.17) | −0.98 (0.27) *** | −0.16 (0.17) | −0.97 (0.27) *** |

| 2 | −0.39 (0.14) ** | −1.27 (0.23) *** | −0.41 (0.16) * | −1.25 (0.26) *** | −0.41 (0.16) * | −1.23 (0.26) *** |

| 3 or more | −0.26 (0.15) | −0.95 (0.25) *** | −0.22 (0.17) | −0.97 (0.27) ** | −0.21 (0.17) | −0.95 (0.28) ** |

| Health (ref: Good or very good) | ||||||

| Fair | −0.42 (0.11) *** | −0.27 (0.17) | −0.31 (0.12) * | −0.32 (0.20) | −0.32 (0.12) * | −0.31 (0.20) |

| Bad or Very Bad | −0.46 (0.17) ** | −0.72 (0.28) * | −0.86 (0.22) *** | −1.07 (0.35) ** | −0.85 (0.22) *** | −1.06 (0.35) ** |

| Subjective income (ref: living comfortably) | ||||||

| Coping | 0.02 (0.10) | 0.05 (0.16) | 0.02 (0.11) | −0.01 (0.17) | 0.03 (0.11) | −0.01 (0.17) |

| Difficult | 0.19 (0.15) | 0.07 (0.23) | 0.24 (0.18) | 0.16 (0.28) | 0.24 (0.18) | 0.16 (0.28) |

| Very Difficult | 0.44 (0.24) | 0.37 (0.36) | 0.57 (0.31) | −0.221 (0.48) | 0.58 (0.31) | −0.22 (0.49) |

| Female labor force participation (mean-centered) | 0.08 (0.04) | 0.10 (0.08) | 0.05 (0.06) | 0.02 (0.11) | 0.07 (0.06) | 0.08 (0.12) |

| Family benefit expenditure (mean-centered) | −0.35 (0.30) | 0.20 (0.51) | 0.44 (0.38) | 0.54 (0.74) | 0.24 (0.38) | 0.487 (0.75) |

| GDP per capita (mean-centered) | −1.89 × 10−5 (1.52 × 10−5) | −3.74 × 10−5 (2.64 × 10−5) | −1.79 × 10−5 (1.78 × 10−5) | −4.27 × 10−5 (3.44 × 10−5) | −3.04 × 10−5 (1.81 × 10−5) | −5.53 × 10−5 (3.57 × 10−5) |

| Constant | 42.73 (0.56) *** | 45.23 (0.96) *** | 42.99 (0.68) | 46.38 (1.28) *** | 43.07 (0.77) *** | 46.31 (1.50) *** |

| Random Effects | ||||||

| sd(_cons) | 0.84 (0.15) | 1.47 (0.26) | 0.77 (0.18) | 1.52 (0.33) | 0.78 (0.17) | 1.56 (0.33) |

| sd(Residual) | 4.88 (0.03) | 7.40 (0.05) | 4.73 (0.03) | 7.34 (0.05) | 4.73 (0.03) | 7.34 (0.05) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kim, E.J.; Cho, M.J. The Association between Assisted Reproduction Technology (ART) and Social Perception of Childbearing Deadline Ages: A Cross-Country Examination of Selected EU Countries. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2111. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18042111

Kim EJ, Cho MJ. The Association between Assisted Reproduction Technology (ART) and Social Perception of Childbearing Deadline Ages: A Cross-Country Examination of Selected EU Countries. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(4):2111. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18042111

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Eun Jung, and Min Jung Cho. 2021. "The Association between Assisted Reproduction Technology (ART) and Social Perception of Childbearing Deadline Ages: A Cross-Country Examination of Selected EU Countries" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 4: 2111. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18042111

APA StyleKim, E. J., & Cho, M. J. (2021). The Association between Assisted Reproduction Technology (ART) and Social Perception of Childbearing Deadline Ages: A Cross-Country Examination of Selected EU Countries. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(4), 2111. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18042111