How Toxic Workplace Environment Effects the Employee Engagement: The Mediating Role of Organizational Support and Employee Wellbeing

Abstract

:1. Introduction

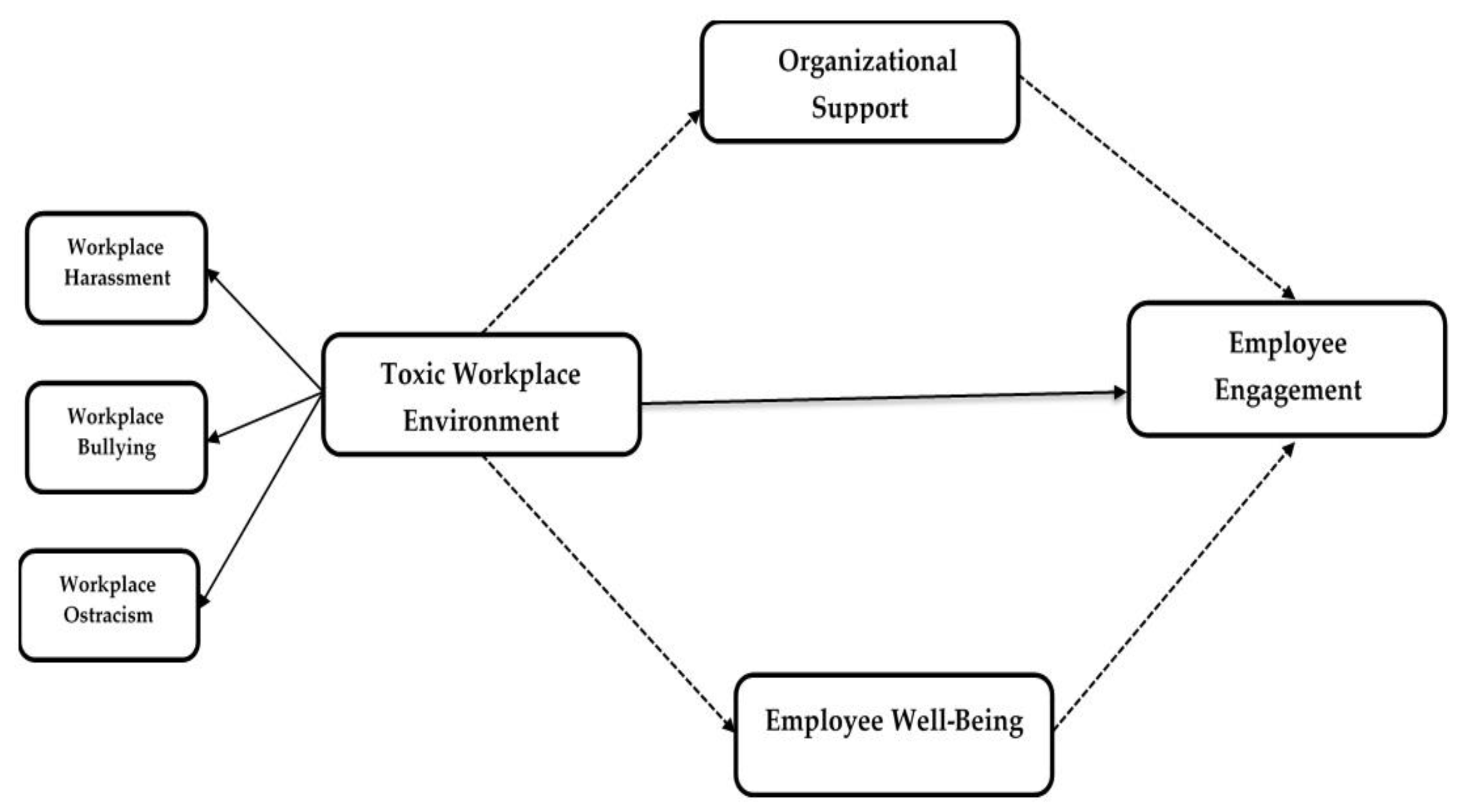

- RQ1:

- How does a toxic workplace environment influence employee engagement?

- RQ2:

- How does organizational support intervene between a toxic workplace environment and employee engagement?

- RQ3:

- How does employee well-being intervene between a toxic workplace environment and employee engagement?

2. Literature Review

2.1. Toxic Workplace Environment

2.2. Employee Engagement

2.3. Organizational Support

2.4. Employee Well-Being

3. Hypotheses Development

3.1. Toxic Workplace Environment and Employee Engagement

3.2. Mediating Effect of Organizational Support

3.3. Mediating Effect of Employee Well-Being

4. Research Methods

4.1. Instrument Development

4.2. Data Collection and Sampling

4.3. Variables and Measures

4.4. Respondents’ Summary

5. Statistical Analysis

Hypotheses Testing

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

8. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Research Instrument | |

| Toxic Workplace Environment | |

| 1. | My supervisor/co-worker/subordinate often appreciates my physical appearance. |

| 2. | My supervisor/co-worker/subordinate spoke rudely to me in public. |

| 3. | My supervisor/co-worker/subordinate often tries to be frank with me and shares dirty jokes with me. |

| 4. | My supervisor/co-worker/subordinate assigns me work that is not of my competence level. |

| 5. | My supervisor/co-worker/subordinate often tries to talk about my personal and sexual life. |

| 6. | My supervisor/co-worker/subordinate tries to maintain distance from me at work. |

| 7. | My supervisor/co-worker/subordinate does not answer my greeting. |

| Organizational Support | |

| 8. | The organization attaches great importance to my work goals and values. |

| 9. | The organization always helps me whenever I am facing a bad time. |

| 10. | The organization is flexible with my working hours, if needed, whenever I guarantee to complete my tasks on time. |

| 11. | The organization provides me enough time to deal with my family matters. |

| Employee Well-Being | |

| 12. | I generally feel positive toward work at my organization. |

| 13. | My supervisor and co-worker check in regularly enough with how I am doing. |

| 14. | When I am stressed, I feel I have the support available for help. |

| 15. | Our organizational culture encourages a balance between work and family life. |

| 16. | Our organization provides aid in stress management. |

| Employee Engagement | |

| 17. | I really throw myself into my job and organization engagement. |

| 18. | I fulfil all responsibilities required by my job. |

| 19. | I willingly give my time to help others who have work-related problems. |

| 20. | I always complete the duties specified in my job description. |

References

- Zeng, Z.; Guo, Y.; Lu, L.; Han, L.; Chen, W.; Ling, L. Mental health status and work environment among workers in small-and medium-sized enterprises in Guangdong, China-a cross-sectional survey. BMC Public Health 2014, 14, 1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Samma, M.; Zhao, Y.; Rasool, S.F.; Han, X.; Ali, S. Exploring the Relationship between Innovative Work Behavior, Job Anxiety, Workplace Ostracism, and Workplace Incivility: Empirical Evidence from Small and Medium Sized Enterprises (SMEs). Healthcare 2020, 8, 508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; He, J.; Du, W.; Zeng, W.; Li, J.; Liu, Y. Survey on occupational hazards of 58 small industrial enterprises in Guangzhou city. Chin. J. Ind. Med. 2008, 21, 186–187. [Google Scholar]

- Amin, A.; Liu, Y.; Yu, J.; Chandio, A.A.; Rasool, S.F.; Luo, J.; Zaman, S. How does energy poverty affect economic development? A panel data analysis of South Asian countries. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2020, 27, 31623–31635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koser, M.; Rasool, S.F.; Samma, M. High Performance Work System is the Accelerator of the Best Fit and Integrated HR-Practices to Achieve the Goal of Productivity: A Case of Textile Sector in Pakistan. Glob. Manag. J. Acad. Corp. Stud. 2018, 8, 10–21. [Google Scholar]

- Rasool, S.F.; Samma, M.; Anjum, A.; Munir, M.; Khan, T.M. Relationship between modern human resource management practices and organizational innovation: Empirical investigation from banking sector of china. Int. Trans. J. Eng. Manag. Appl. Sci. Technol. 2019, 10, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, T.-J.; Wu, Y.J. Innovative work behaviors, employee engagement, and surface acting. Manag. Decis. 2019, 57, 3200–3216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birdi, K.; Leach, D.; Magadley, W. The relationship of individual capabilities and environmental support with different facets of designers’ innovative behavior. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2016, 33, 19–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.J.; Kim, J. Does negative feedback benefit (or harm) recipient creativity? The role of the direction of feedback flow. Acad. Of Manag. J. 2020, 63, 584–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasool, S.F.; Wang, M.; Zhang, Y.; Samma, M. Sustainable Work Performance: The Roles of Workplace Violence and Occupational Stress. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Taylor, J.L.; Rew, L. A systematic review of the literature: Workplace violence in the emergency department. J. Clin. Nurs. 2011, 20, 1072–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berquist, R.; St-Pierre, I.; Holmes, D. Uncaring Nurses: Mobilizing Power, Knowledge, Difference, and Resistance to Explain Workplace Violence in Academia. Res. Theory Nurs. Pract. 2018, 32, 199–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avey, J.B.; Luthans, F.; Smith, R.M.; Palmer, N.F. Impact of positive psychological capital on employee well-being over time. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2010, 15, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Maslow, A.H. A Dynamic Theory of Human Motivation; Howard Allen Publishers: London, UK, 1958. [Google Scholar]

- Odoardi, C.; Montani, F.; Boudrias, J.-S.; Battistelli, A. Linking managerial practices and leadership style to innovative work behavior. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2015, 36, 545–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, J.; Sağsan, M. Impact of knowledge management practices on green innovation and corporate sustainable development: A structural analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 229, 611–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Bartol, K.M. Linking empowering leadership and employee creativity: The influence of psychological empowerment, intrinsic motivation, and creative process engagement. Acad. Manag. J. 2010, 53, 107–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yuan, F.; Woodman, R.W. Innovative behavior in the workplace: The role of performance and image outcome expectations. Acad. Manag. J. 2010, 53, 323–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- De Clercq, D.; Haq, I.U.; Azeem, M.U. The relationship between workplace incivility and depersonalization towards co-workers: Roles of job-related anxiety, gender, and education. J. Manag. Organ. 2020, 26, 219–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vinokur, A.D.; Pierce, P.F.; Lewandowski-Romps, L.; Hobfoll, S.E.; Galea, S. Effects of war exposure on air force personnel’s mental health, job burnout and other organizational related outcomes. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2011, 16, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Azuma, K.; Ikeda, K.; Kagi, N.; Yanagi, U.; Osawa, H. Prevalence and risk factors associated with nonspecific building-related symptoms in office employees in Japan: Relationships between work environment, Indoor Air Quality, and occupational stress. Indoor Air 2015, 25, 499–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, L.A.; Perhats, C.; Delao, A.M.; Clark, P.R. Workplace aggression as cause and effect: Emergency nurses’ experiences of working fatigued. Int. Emerg. Nurs. 2017, 33, 48–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anjum, A.; Ming, X. Combating toxic workplace environment: An empirical study in the context of Pakistan. J. Model. Manag. 2018, 13, 675–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgess, E.O.; Barmon, C.; Moorhead, J.R., Jr.; Perkins, M.M.; Bender, A.A. “That is so common everyday… Everywhere you go”: Sexual harassment of workers in assisted living. J. Appl. Gerontol. 2018, 37, 397–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leymann, H. Mobbing and psychological terror at workplaces. Violence Vict. 1990, 5, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiset, J.; Robinson, M.A. Considerations related to intentionality and omissive acts in the study of workplace aggression and mistreatment. Ind. Organ. Psychol. 2018, 11, 112–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, C.K.; Walter, F.; Huang, X. Supervisors’ emotional exhaustion and abusive supervision: The moderating roles of perceived subordinate performance and supervisor self-monitoring. J. Organ. Behav. 2017, 38, 1151–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanwar, K.; Kumar, A. Employer brand, person-organisation fit and employer of choice. Pers. Rev. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Albrecht, S. Work engagement: Current trends. Career Dev. Int. 2018, 23, 4–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Bakker, A.B. Job demands, job resources, and their relationship with burnout and engagement: A multi-sample study. J. Organ. Behav. Int. J. Ind. Occup. Organ. Psychol. Behav. 2004, 25, 293–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kaliannan, M.; Adjovu, S.N. Effective employee engagement and organizational success: A case study. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 172, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, Z.; Zaman, S.; Rasool, S.F.; uz Zaman, Q.; Amin, A. Exploring the Relationships Between a Toxic Workplace Environment, Workplace Stress, and Project Success with the Moderating Effect of Organizational Support: Empirical Evidence from Pakistan. Risk Manag. Healthc. Policy 2020, 13, 1055–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Chelladurai, P.; Trail, G.T. A model of volunteer retention in youth sport. J. Sport Manag. 2007, 21, 151–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobbio, A.; Bellan, M.; Manganelli, A.M. Empowering leadership, perceived organizational support, trust, and job burnout for nurses: A study in an Italian general hospital. Health Care Manag. Rev. 2012, 37, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leung, M.-y.; Zhang, H.; Skitmore, M. Effects of organizational supports on the stress of construction estimation participants. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2008, 134, 84–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, O.; Payaud, M.; Merunka, D.; Valette-Florence, P. The impact of corporate social responsibility on organizational commitment: Exploring multiple mediation mechanisms. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 125, 563–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danna, K.; Griffin, R.W. Health and well-being in the workplace: A review and synthesis of the literature. J. Manag. 1999, 25, 357–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, E.; Kim, H.; Uysal, M. Life satisfaction and support for tourism development. Ann. Tour. Res. 2015, 50, 84–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, C.-M.; Cheng, H.-L.; Huang, H.-Y.; Chen, C.-F. Exploring individuals’ subjective well-being and loyalty towards social network sites from the perspective of network externalities: The Facebook case. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2013, 33, 539–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.P.; Mishra, P.S. Antecedents and consequences of employee engagement: A critical analysis of literature review. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2014, 3, 73–86. [Google Scholar]

- Arnetz, J.; Hamblin, L.E.; Sudan, S.; Arnetz, B. Organizational determinants of workplace violence against hospital workers. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2018, 60, 693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imran, M.Y.; Elahi, N.S.; Abid, G.; Ashfaq, F.; Ilyas, S. Impact of perceived organizational support on work engagement: Mediating mechanism of thriving and flourishing. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2020, 6, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, T.M.; Gang, B.; Fareed, Z.; Khan, A. How does CEO tenure affect corporate social and environmental disclosures in China? Moderating role of information intermediaries and independent board. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 28, 9204–9220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, T.M.; Bai, G.; Fareed, Z.; Quresh, S.; Khalid, Z.; Khan, W.A. CEO Tenure, CEO Compensation, Corporate Social & Environmental Performance in China. The Moderating Role of Coastal and Non-Coastal Areas. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 3815. [Google Scholar]

- Benefiel, M. The second half of the journey: Spiritual leadership for organizational transformation. Leadersh. Q. 2005, 16, 723–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, J.; Milliman, J. Creating effective core organizational values: A spiritual leadership approach. Intl J. Public Adm. 2008, 31, 439–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fry, L.W.; Latham, J.R.; Clinebell, S.K.; Krahnke, K. Spiritual leadership as a model for performance excellence: A study of Baldrige award recipients. J. Manag. Spiritual. Relig. 2017, 14, 22–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erkutlu, H. The impact of organizational culture on the relationship between shared leadership and team proactivity. Team Perform. Manag. Int. J. 2012, 18, 102–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacalone, R.A.; Jurkiewicz, C.L. Handbook of Workplace Spirituality and Organizational Performance; Me Sharpe: Oxfordshire, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, J.V.; Hall, E.M. Job strain, work place social support, and cardiovascular disease: A cross-sectional study of a random sample of the Swedish working population. Am. J. Public Health 1988, 78, 1336–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E.; Verbeke, W. Using the job demands-resources model to predict burnout and performance; School of Business Administration, The University of Michigan: Ann Arbor, MI, USA; The Society of Human Resources Management: Alexandria, VA, USA, 2004; Volume 43, pp. 83–104. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, M.; Yang, S.; Qiu, T.; Gao, X.; Wu, H. Moderating role of self-esteem between perceived organizational support and subjective well-being in Chinese nurses: A cross-sectional study. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 2315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, L.; Wang, Y.; Qian, W.; Lu, H. Leader humor and employee job crafting: The role of employee-perceived organizational support and work engagement. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 2592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X.; Zhang, X.; Chen, M.; Liu, J.; Wu, C. The Influence of Perceived Organizational Support on Police Job Burnout: A Moderated Mediation Model. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, X.; Rasool, S.F.; Ma, D. The Relationship between Workplace Violence and Innovative Work Behavior: The Mediating Roles of Employee Wellbeing. Healthcare 2020, 8, 332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajalingam, D. The Impact of Workplace Bullying and Repeated Social Defeat on Health and Behavioral Outcomes: A Biopsychosocial Perspective; University of Bergen: Bergen, Norway, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Dos Santos, L.M. Stress, Burnout, and Turnover Issues of Black Expatriate Education Professionals in South Korea: Social Biases, Discrimination, and Workplace Bullying. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, Y.W. The Relationship between Workplace Ostracism, TMX, Task Interdependence, and Task Performance: A Moderated Mediation Model. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marin-Garcia, J.A.; Bonavia, T.; Losilla, J.-M. Changes in the Association between European Workers’ Employment Conditions and Employee Well-Being in 2005, 2010 and 2015. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- He, J.; Morrison, A.M.; Zhang, H. Improving millennial employee well-being and task performance in the hospitality industry: The interactive effects of HRM and responsible leadership. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Arenas, A.; Giorgi, G.; Montani, F.; Mancuso, S.; Perez, J.F.; Mucci, N.; Arcangeli, G. Workplace bullying in a sample of Italian and Spanish employees and its relationship with job satisfaction, and psychological well-being. Front. Psychol. 2015, 6, 1912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, Y.-F. Modeling predictors of restaurant employees’ green behavior: Comparison of six attitude-behavior models. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 58, 66–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R.R.; Sharma, N.P. Opening the gender diversity black box: Causality of perceived gender equity and locus of control and mediation of work engagement in employee well-being. Front. Psychol. 2015, 6, 1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fotiadis, A.; Abdulrahman, K.; Spyridou, A. The mediating roles of psychological autonomy, competence and relatedness on work-life balance and well-being. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heeringa, S.G.; West, B.T.; Berglund, P.A. Applied Survey Data Analysis; Chapman and Hall/CRC: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hennessy, J.L.; Patterson, D.A. Computer Architecture: A Quantitative Approach; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Rasool, S.F.; Maqbool, R.; Samma, M.; Zhao, Y.; Anjum, A. Positioning Depression as a Critical Factor in Creating a Toxic Workplace Environment for Diminishing Worker Productivity. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Anjum, A.; Ming, X.; Siddiqi, A.; Rasool, S. An empirical study analyzing job productivity in toxic workplace environments. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ahmed, M.; Zehou, S.; Raza, S.A.; Qureshi, M.A.; Yousufi, S.Q. Impact of CSR and environmental triggers on employee green behavior: The mediating effect of employee well-being. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 2225–2239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, Z.; Shenbei, Z.; Hanif, A.M. Workplace Violence and Employee Engagement: The Mediating Role of Work Environment and Organizational Culture. SAGE Open 2020, 10, 2158244020935885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM); Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacherjee, A.; Perols, J.; Sanford, C. Information technology continuance: A theoretic extension and empirical test. J. Comput. Inf. Syst. 2008, 49, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasool, S.F.; Samma, M.; Wang, M.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, Y. How human resource management practices translate into sustainable organizational performance: The mediating role of product, process and knowledge innovation. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2019, 12, 1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error: Algebra and Statistics; Sage Publications Sage CA: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Stuber, F.; Seifried-Dübon, T.; Rieger, M.A.; Zipfel, S.; Gündel, H.; Junne, F.; Contributors of the SEEGEN Consortium. Investigating the Role of Stress-Preventive Leadership in the Workplace Hospital: The Cross-Sectional Determination of Relational Quality by Transformational Leadership. Front. Psychiatry 2019, 10, 622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wu, L.; Wei, L.; Hui, C. Dispositional antecedents and consequences of workplace ostracism: An empirical examination. Front. Bus. Res. China 2011, 5, 23–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kurtessis, J.N.; Eisenberger, R.; Ford, M.T.; Buffardi, L.C.; Stewart, K.A.; Adis, C.S. Perceived organizational support: A meta-analytic evaluation of organizational support theory. J. Manag. 2017, 43, 1854–1884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tremblay, M.; Gaudet, M.-C.; Vandenberghe, C. The role of group-level perceived organizational support and collective affective commitment in the relationship between leaders’ directive and supportive behaviors and group-level helping behaviors. Pers. Rev. 2019, 48, 417–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariza-Montes, A.; Leal-Rodríguez, A.L.; Ramírez-Sobrino, J.; Molina-Sánchez, H. Safeguarding Health at the Workplace: A Study of Work Engagement, Authenticity and Subjective Wellbeing among Religious Workers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tziner, A.; Rabenu, E.; Radomski, R.; Belkin, A. Work stress and turnover intentions among hospital physicians: The mediating role of burnout and work satisfaction. Rev. Psicol. Trab. Y Las Organ. 2015, 31, 207–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Caesens, G.; Stinglhamber, F. Toward a More Nuanced View on Organizational Support Theory. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Hao, S.; Ding, K.; Feng, X.; Li, G.; Liang, X. The impact of organizational support on employee performance. Empl. Relat. Int. J. 2020, 42, 166–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuck, B.; Reio, T.G., Jr. Employee engagement and well-being: A moderation model and implications for practice. J. Leadersh. Organ. Stud. 2014, 21, 43–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heffernan, M.; Dundon, T. Cross-level effects of high-performance work systems (HPWS) and employee well-being: The mediating effect of organisational justice. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2016, 26, 211–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chumg, H.-F.; Cooke, L.; Fry, J.; Hung, I.-H. Factors affecting knowledge sharing in the virtual organisation: Employees’ sense of well-being as a mediating effect. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 44, 70–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Su, L.; Swanson, S.R. Perceived corporate social responsibility’s impact on the well-being and supportive green behaviors of hotel employees: The mediating role of the employee-corporate relationship. Tour. Manag. 2019, 72, 437–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Guchait, P.; Paşamehmetoğlu, A. Why should errors be tolerated? Perceived organizational support, organization-based self-esteem and psychological well-being. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 32, 1987–2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Category | Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 164 | 54.44 |

| Female | 137 | 45.51 | |

| Working experience | 5–10 years | 119 | 39.53 |

| 10–15 years | 102 | 33.88 | |

| Above 15 years | 80 | 26.57 | |

| Positions | Senior manager | 81 | 26.91 |

| Middle manager | 108 | 35.88 | |

| Administrative staff | 112 | 37.20 | |

| Education | Post-graduate | 90 | 29.90 |

| Undergraduate | 145 | 48.17 | |

| Others | 66 | 21.92 |

| Constructs | Loading | Alpha | rho_A | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Toxic Workplace Environment | 0.935 | 0.94 | 0.946 | 0.685 | |

| TWE1 | 0.874 | ||||

| TWE2 | 0.842 | ||||

| TWE3 | 0.798 | ||||

| TWE4 | 0.792 | ||||

| TWE5 | 0.810 | ||||

| TWE6 | 0.840 | ||||

| TWE7 | 0.792 | ||||

| TWE8 | 0.868 | ||||

| Organizational Support | 0.784 | 0.795 | 0.862 | 0.612 | |

| OS1 | 0.680 | ||||

| OS2 | 0.820 | ||||

| OS3 | 0.887 | ||||

| OS4 | 0.725 | ||||

| Employee Well-Being | 0.843 | 0.846 | 0.889 | 0.616 | |

| EW1 | 0.789 | ||||

| EW2 | 0.795 | ||||

| EW3 | 0.829 | ||||

| EW4 | 0.716 | ||||

| EW5 | 0.791 | ||||

| Employee Engagement | 0.759 | 0.776 | 0.846 | 0.578 | |

| EE1 | 0.758 | ||||

| EE2 | 0.818 | ||||

| EE3 | 0.733 | ||||

| EE4 | 0.730 | ||||

| Constructs | EE | EW | OS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Employee engagement | |||

| Employee well-being | 0.786 | ||

| Organizational support | 0.759 | 0.533 | |

| Toxic workplace environment | 0.244 | 0.157 | 0.166 |

| Direct Paths | Coefficients | Mean | SD | t-Values | p-Values | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TWE → EE | −0.097 | −0.098 | 0.037 | 2.590 | 0.010 | Significant |

| TWE → OS | −0.145 | −0.155 | 0.054 | 2.812 | 0.005 | Significant |

| OS → EE | 0.376 | 0.378 | 0.044 | 8.554 | 0.000 | Significant |

| TWE → EW | −0.152 | −0.152 | 0.059 | 2.465 | 0.014 | Significant |

| EW → EE | 0.467 | 0.466 | 0.05 | 9.378 | 0.000 | Significant |

| Indirect Paths | ||||||

| TWE →EW → EE | −0.062 | −0.068 | 0.024 | 2.601 | 0.009 | Significant |

| TWE → OS → EE | −0.061 | −0.067 | 0.023 | 2.606 | 0.009 | Significant |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rasool, S.F.; Wang, M.; Tang, M.; Saeed, A.; Iqbal, J. How Toxic Workplace Environment Effects the Employee Engagement: The Mediating Role of Organizational Support and Employee Wellbeing. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2294. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18052294

Rasool SF, Wang M, Tang M, Saeed A, Iqbal J. How Toxic Workplace Environment Effects the Employee Engagement: The Mediating Role of Organizational Support and Employee Wellbeing. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(5):2294. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18052294

Chicago/Turabian StyleRasool, Samma Faiz, Mansi Wang, Minze Tang, Amir Saeed, and Javed Iqbal. 2021. "How Toxic Workplace Environment Effects the Employee Engagement: The Mediating Role of Organizational Support and Employee Wellbeing" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 5: 2294. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18052294

APA StyleRasool, S. F., Wang, M., Tang, M., Saeed, A., & Iqbal, J. (2021). How Toxic Workplace Environment Effects the Employee Engagement: The Mediating Role of Organizational Support and Employee Wellbeing. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(5), 2294. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18052294