Estimating the Economic Burden of Low Health Literacy in the Blacktown Community in Sydney, Australia: A Population-Based Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Aims and Objectives

- To estimate the cost of LHL to the health care system, the government, employers/businesses, and at the individual and household levels.

- To estimate the cost of LHL by age group area of health service, and by chronic health condition.

- To estimate the burden of disease associated with LHL.

2.2. Study Design and Data Sources

2.3. Source Population

2.4. Health Literacy Questionnaire

2.5. Costing Methodology

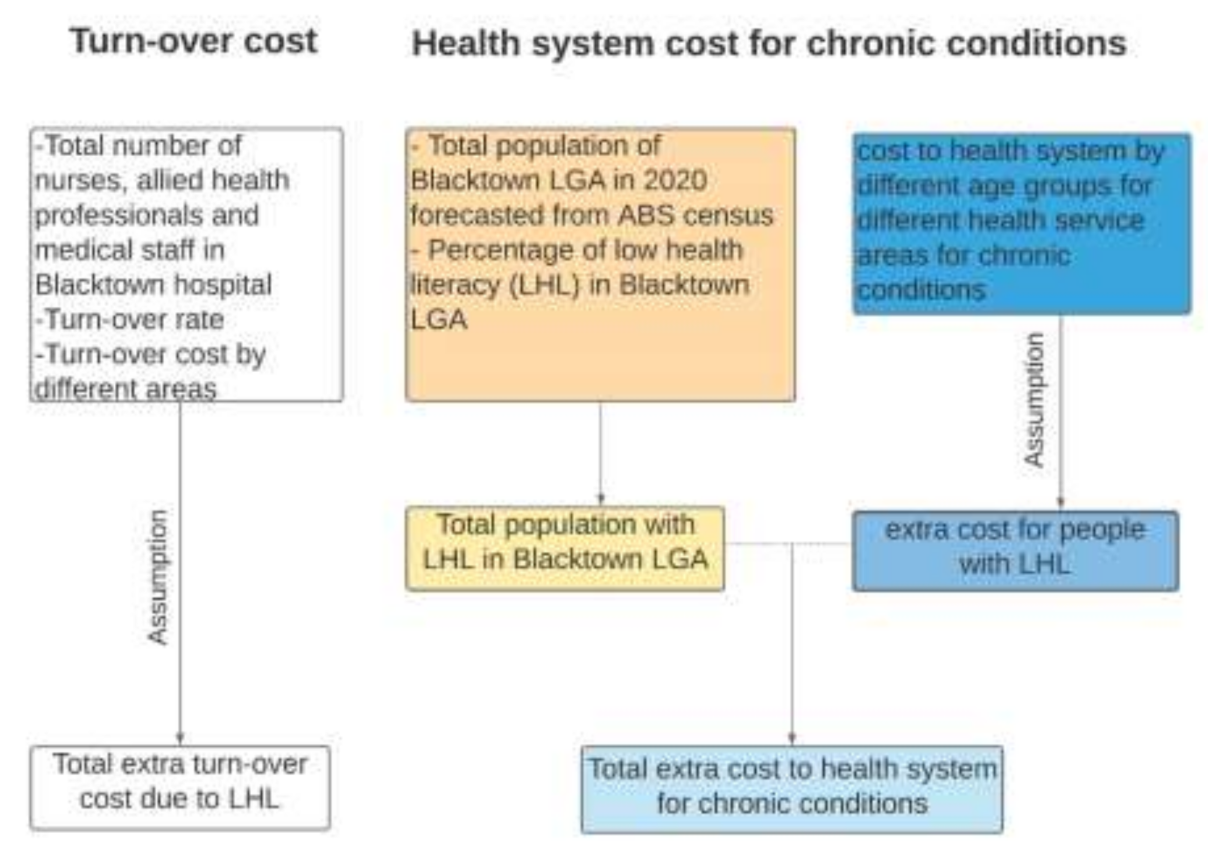

2.5.1. Costs to the Health Care System

2.5.2. Costs to Individuals, Households, and Carers

2.5.3. Costs to the Employer/Business

2.5.4. Costs to the Government

2.5.5. Burden of Disease Due to LHL

3. Results

3.1. Prevalence of LHL in the Blacktown LGA

3.2. Total Extra/Delta Direct Health Care Costs

3.2.1. Domain 6—Engagement with Health Care Providers

3.2.2. Domain 9—Understanding Health Care Information in Order to Take Action

3.2.3. Out of Pocket Costs

3.3. Total Extra/Delta Indirect Health Care Costs

3.3.1. Costs to the Employer/Business

3.3.2. Costs to Individuals and Households

3.3.3. Costs to the Government

3.4. Burden of Disease Due to LHL

4. Discussion

4.1. Strengths and Limitations

4.2. Policy Implications and Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Age Groups | Allied Health and Other Services | Diagnostic Tests | General Practitioner | Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme | Public Hospital Admitted Patient | Public Hospital Emergency Department | Public Hospital Outpatient | Specialist Services | Total Services |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20–24 years | 224 | 10,966 | 30,372 | 4282 | 33,446 | 7051 | 11,685 | 6477 | 104,503 |

| 25–34 years | 71 | 3813 | 7703 | 1870 | 9301 | 1911 | 4029 | 2013 | 30,711 |

| 35–44 years | 609 | 21,380 | 46,342 | 27,686 | 90,545 | 17,038 | 19,709 | 16,880 | 240,189 |

| 45–54 years | 1113 | 27,534 | 58,310 | 82,743 | 197,814 | 32,788 | 28,102 | 28,519 | 456,923 |

| 55–64 years | 851 | 15,749 | 30,421 | 84,154 | 161,247 | 21,496 | 19,546 | 20,351 | 353,815 |

| 65 years and over | 1291 | 13,342 | 29,090 | 120,164 | 258,808 | 30,343 | 22,093 | 19,595 | 494,726 |

| Total (inflation adjusted) | 4158 | 92,784 | 202,239 | 320,900 | 751,162 | 110,626 | 105,164 | 93,835 | 1,680,868 |

| Age Groups | Allied Health and Other Services | Diagnostic Tests | General Practitioner | Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme | Public Hospital Admitted Patient | Public Hospital Emergency Department | Public Hospital Outpatient | Specialist Services | Total Services |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20–24 years | 2781 | 31,233 | 31,108 | 35,442 | 34,101 | 11,837 | 38,073 | 5816 | 190,391 |

| 25–34 years | 962 | 9503 | 7776 | 13,244 | 8247 | 2698 | 13,701 | 1799 | 57,930 |

| 35–44 years | 8607 | 63,358 | 45,045 | 119,018 | 65,008 | 15,912 | 60,584 | 13,298 | 390,830 |

| 45–54 years | 14,626 | 91,119 | 55,511 | 177,845 | 120,473 | 18,253 | 65,446 | 19,913 | 563,186 |

| 55–64 years | 10,367 | 53,311 | 28,876 | 100,414 | 93,162 | 7638 | 38,683 | 13,837 | 346,288 |

| 65 years and over | 13,159 | 41,525 | 28,501 | 83,714 | 111,995 | 6974 | 38,229 | 13,960 | 338,057 |

| Total (inflation adjusted) | 50,501 | 290,049 | 196,817 | 529,677 | 432,986 | 63,312 | 254,716 | 68,623 | 1,886,681 |

| Age Groups | Allied Health and Other Services | Diagnostic Tests | General Practitioner | Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme | Public Hospital Admitted Patient | Public Hospital Emergency Department | Public Hospital Outpatient | Specialist Services | Total Services |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20–24 years | 95,779 | 4791 | 48,415 | 32,283 | 182,462 | 37,153 | 29,514 | 26,899 | 457,296 |

| 25–34 years | 22,621 | 1506 | 11,438 | 10,297 | 45,868 | 6970 | 9022 | 6497 | 114,219 |

| 35–44 years | 120,839 | 9102 | 64,236 | 81,736 | 251,151 | 35,292 | 54,718 | 41,693 | 658,767 |

| 45–54 years | 111,592 | 12,399 | 71,395 | 95,324 | 209,393 | 29,276 | 47,381 | 46,621 | 623,381 |

| 55–64 years | 40,378 | 7215 | 32,721 | 38,773 | 72,867 | 8790 | 16,368 | 20,133 | 237,245 |

| 65 years and over | 18,212 | 6049 | 27,071 | 24,041 | 70,118 | 7660 | 16,105 | 9184 | 178,440 |

| Total (inflation adjusted) | 409,421 | 41,063 | 255,275 | 282,453 | 831,858 | 125,142 | 173,109 | 151,027 | 2,269,348 |

| Age Groups | Allied Health and Other Services | Diagnostic Tests | General Practitioner | Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme | Public Hospital Admitted Patient | Public Hospital Emergency Department | Public Hospital Outpatient | Specialist Services | Total Services |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20–24 years | 63 | 5027 | 8405 | 5562 | 18,993 | 297 | 11,251 | 6672 | 56,270 |

| 25–34 years | 20 | 1757 | 2241 | 2615 | 6676 | 94 | 3712 | 2359 | 19,474 |

| 35–44 years | 165 | 12,339 | 14,794 | 40,297 | 64,766 | 866 | 31,165 | 23,650 | 188,042 |

| 45–54 years | 304 | 18,575 | 22,022 | 90,097 | 146,472 | 2020 | 67,153 | 50,909 | 397,552 |

| 55–64 years | 224 | 11,852 | 13,992 | 71,737 | 117,094 | 1632 | 54,031 | 39,709 | 310,271 |

| 65 years and over | 323 | 10,793 | 15,517 | 79,212 | 125,912 | 1715 | 54,312 | 38,691 | 326,475 |

| Total (inflation adjusted) | 1099 | 60,343 | 76,970 | 289,520 | 479,912 | 6625 | 221,624 | 161,990 | 1,298,083 |

| Age Groups | Allied Health and Other Services | Diagnostic Tests | General Practitioner | Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme | Public Hospital Admitted Patient | Public Hospital Emergency Department | Public Hospital Outpatient | Specialist Services | Total Services |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20–24 years | 31 | 6633 | 4239 | 5051 | 21,201 | 6253 | 6290 | 1748 | 51,446 |

| 25–34 years | 10 | 2119 | 1064 | 1841 | 6265 | 1495 | 2265 | 551 | 15,610 |

| 35–44 years | 86 | 11,062 | 6130 | 17,299 | 56,188 | 8801 | 13,365 | 4314 | 117,245 |

| 45–54 years | 157 | 13,377 | 7534 | 27,306 | 110,725 | 11,336 | 20,726 | 6474 | 197,635 |

| 55–64 years | 120 | 7439 | 3923 | 15,935 | 77,787 | 5892 | 13,471 | 4299 | 128,866 |

| 65 years and over | 182 | 6030 | 3840 | 15,613 | 109,107 | 6135 | 9595 | 3972 | 154,474 |

| Total (inflation adjusted) | 585 | 46,660 | 26,730 | 83,045 | 381,274 | 39,912 | 65,712 | 21,359 | 665,277 |

| Age Groups | Allied Health and Other Services | Diagnostic Tests | General Practitioner | Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme | Public Hospital Admitted Patient | Public Hospital Emergency Department | Public Hospital Outpatient | Specialist Services | Total Services |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20–24 years | 103 | 4891 | 17,418 | 15,199 | 27,233 | 7778 | 8314 | 4221 | 85,157 |

| 25–34 years | 33 | 1364 | 4326 | 4085 | 5524 | 1426 | 2850 | 1399 | 21,007 |

| 35–44 years | 281 | 9070 | 25,073 | 26,650 | 35,880 | 7977 | 12,715 | 11,205 | 128,851 |

| 45–54 years | 514 | 13,293 | 30,877 | 40,498 | 57,387 | 11,070 | 14,125 | 16,467 | 184,231 |

| 55–64 years | 393 | 7996 | 16,100 | 30,004 | 45,235 | 7553 | 8481 | 10,030 | 125,792 |

| 65 years and over | 596 | 6527 | 15,682 | 40,531 | 69,606 | 12,245 | 7900 | 7842 | 160,929 |

| Total (inflation adjusted) | 1921 | 43,141 | 109,477 | 156,968 | 240,864 | 48,049 | 54,385 | 51,165 | 705,970 |

| Age Groups | Allied Health and Other Services | Diagnostic Tests | General Practitioner | Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme | Public Hospital Admitted Patient | Public Hospital Emergency Department | Public Hospital Outpatient | Specialist Services | Total Services |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20–24 years | 667 | 8873 | 12,899 | 9138 | 9819 | 2140 | 12,977 | 1962 | 58,475 |

| 25–34 years | 217 | 2960 | 3240 | 4700 | 2839 | 370 | 4595 | 610 | 19,531 |

| 35–44 years | 1991 | 16,817 | 18,968 | 46,668 | 23,341 | 1868 | 20,520 | 4410 | 134,583 |

| 45–54 years | 3871 | 21,772 | 23,957 | 59,555 | 42,445 | 2038 | 26,465 | 6289 | 186,392 |

| 55–64 years | 3012 | 12,255 | 12,941 | 51,170 | 30,588 | 932 | 17,377 | 4129 | 132,404 |

| 65 years and over | 3827 | 10,324 | 12,852 | 46,090 | 36,844 | 861 | 14,175 | 3823 | 128,796 |

| Total (inflation adjusted) | 13,585 | 73,001 | 84,858 | 217,321 | 145,876 | 8209 | 96,109 | 21,223 | 660,182 |

| Age Groups | Allied Health and Other Services | Diagnostic Tests | General Practitioner | Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme | Public Hospital Admitted Patient | Public Hospital Emergency Department | Public Hospital Outpatient | Specialist Services | Total Services |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20–24 years | 74 | 3621 | 10,030 | 1414 | 11,045 | 2328 | 3859 | 2139 | 34,510 |

| 25–34 years | 71 | 3813 | 7703 | 1870 | 9301 | 1911 | 4029 | 2013 | 30,711 |

| 35–44 years | 300 | 10,546 | 22,859 | 13,657 | 44,663 | 8404 | 9722 | 8326 | 118,477 |

| 45–54 years | 790 | 19,552 | 41,408 | 58,758 | 140,474 | 23,284 | 19,956 | 20,252 | 324,474 |

| 55–64 years | 319 | 5906 | 11,408 | 31,558 | 60,468 | 8061 | 7330 | 7632 | 132,682 |

| 65 years and over | 3196 | 33,041 | 72,041 | 297,581 | 640,926 | 75,143 | 54,711 | 48,526 | 1,225,165 |

| Total (inflation adjusted) | 4750 | 76,480 | 165,448 | 404,838 | 906,876 | 119,131 | 99,607 | 88,888 | 1,866,018 |

| Age Groups | Allied Health and Other Services | Diagnostic tests | General Practitioner | Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme | Public Hospital Admitted Patient | Public Hospital Emergency Department | Public Hospital Outpatient | Specialist Services | Total Services |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20–24 years | 918 | 10,314 | 10,273 | 11,704 | 11,261 | 3909 | 12,573 | 1921 | 62,873 |

| 25–34 years | 962 | 9503 | 7776 | 13,244 | 8247 | 2698 | 13,701 | 1799 | 57,930 |

| 35–44 years | 4245 | 31,252 | 22,219 | 58,707 | 32,066 | 7849 | 29,884 | 6559 | 192,781 |

| 45–54 years | 10,386 | 64,706 | 39,420 | 126,292 | 85,551 | 12,962 | 46,475 | 14,141 | 399,933 |

| 55–64 years | 3888 | 19,992 | 10,828 | 37,655 | 34,936 | 2864 | 14,506 | 5189 | 129,858 |

| 65 years and over | 32,587 | 102,836 | 70,582 | 207,313 | 277,350 | 17,271 | 94,672 | 34,572 | 837,183 |

| Total (inflation adjusted) | 52,987 | 238,603 | 161,098 | 454,916 | 449,411 | 47,553 | 211,811 | 64,180 | 1,680,559 |

| Age Groups | Allied Health and Other Services | Diagnostic Tests | General Practitioner | Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme | Public Hospital Admitted Patient | Public Hospital Emergency Department | Public Hospital Outpatient | Specialist Services | Total Services |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20–24 years | 31,629 | 1582 | 15,988 | 10,661 | 60,255 | 12,269 | 9747 | 8883 | 151,014 |

| 25–34 years | 22,621 | 1506 | 11,438 | 10,297 | 45,868 | 6970 | 9022 | 6497 | 114,219 |

| 35–44 years | 59,606 | 4490 | 31,685 | 40,317 | 123,883 | 17,408 | 26,990 | 20,565 | 324,944 |

| 45–54 years | 79,245 | 8805 | 50,699 | 67,693 | 148,695 | 20,790 | 33,647 | 33,107 | 442,681 |

| 55–64 years | 15,142 | 2706 | 12,270 | 14,540 | 27,325 | 3296 | 6138 | 7550 | 88,967 |

| 65 years and over | 45,101 | 14,980 | 67,039 | 59,535 | 173,644 | 18,970 | 39,884 | 22,743 | 441,896 |

| Total (inflation adjusted) | 253,343 | 34,069 | 189,120 | 203,043 | 579,670 | 79,704 | 125,428 | 99,346 | 1,563,723 |

| Age Groups | Allied Health and Other Services | Diagnostic Tests | General Practitioner | Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme | Public Hospital Admitted Patient | Public Hospital Emergency Department | Public Hospital Outpatient | Specialist Services | Total Services |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20–24 years | 21 | 1660 | 2776 | 1837 | 6272 | 98 | 3716 | 2203 | 18,583 |

| 25–34 years | 20 | 1757 | 2241 | 2615 | 6676 | 94 | 3712 | 2359 | 19,474 |

| 35–44 years | 81 | 6087 | 7297 | 19,877 | 31,946 | 427 | 15,372 | 11,665 | 92,752 |

| 45–54 years | 216 | 13,190 | 15,638 | 63,980 | 104,014 | 1435 | 47,687 | 36,152 | 282,312 |

| 55–64 years | 84 | 4444 | 5247 | 26,902 | 43,910 | 612 | 20,262 | 14,891 | 116,352 |

| 65 years and over | 801 | 26,729 | 38,427 | 196,165 | 311,814 | 4246 | 134,502 | 95,816 | 808,500 |

| Total (inflation adjusted) | 1223 | 53,868 | 71,625 | 311,375 | 504,633 | 6912 | 225,250 | 163,087 | 1,337,973 |

| Age Groups | Allied Health and Other Services | Diagnostic Tests | General Practitioner | Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme | Public Hospital Admitted Patient | Public Hospital Emergency Department | Public Hospital Outpatient | Specialist Services | Total Services |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20–24 years | 10 | 2190 | 1400 | 1668 | 7001 | 2065 | 2077 | 577 | 16,988 |

| 25–34 years | 10 | 2119 | 1064 | 1841 | 6265 | 1495 | 2265 | 551 | 15,610 |

| 35–44 years | 42 | 5457 | 3024 | 8533 | 27,715 | 4341 | 6593 | 2128 | 57,833 |

| 45–54 years | 111 | 9500 | 5350 | 19,391 | 78,629 | 8050 | 14,718 | 4597 | 140,346 |

| 55–64 years | 45 | 2790 | 1471 | 5976 | 29,170 | 2210 | 5051 | 1612 | 48,325 |

| 65 years and over | 450 | 14,933 | 9510 | 38,666 | 270,199 | 15,194 | 23,762 | 9836 | 382,550 |

| Total (inflation adjusted) | 669 | 36,988 | 21,819 | 76,074 | 418,980 | 33,354 | 54,467 | 19,303 | 661,653 |

| Age Groups | Allied Health and Other Services | Diagnostic Tests | General Practitioner | Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme | Public Hospital Admitted Patient | Public Hospital Emergency Department | Public Hospital Outpatient | Specialist Services | Total Services |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20–24 years | 34 | 1615 | 5752 | 5019 | 8993 | 2568 | 2746 | 1394 | 28,121 |

| 25–34 years | 33 | 1364 | 4326 | 4085 | 5524 | 1426 | 2850 | 1399 | 21,007 |

| 35–44 years | 139 | 4474 | 12,368 | 13,145 | 17,698 | 3935 | 6272 | 5527 | 63,558 |

| 45–54 years | 365 | 9440 | 21,927 | 28,759 | 40,752 | 7861 | 10,031 | 11,694 | 130,829 |

| 55–64 years | 147 | 2999 | 6038 | 11,251 | 16,963 | 2832 | 3180 | 3761 | 47,171 |

| 65 years and over | 1476 | 16,163 | 38,836 | 100,374 | 172,376 | 30,324 | 19,563 | 19,421 | 398,533 |

| Total (inflation adjusted) | 2194 | 36,054 | 89,246 | 162,634 | 262,306 | 48,947 | 44,642 | 43,197 | 689,220 |

| Age Groups | Allied Health and Other Services | Diagnostic Tests | General Practitioner | Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme | Public Hospital Admitted Patient | Public Hospital Emergency Department | Public Hospital Outpatient | Specialist Services | Total Services |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20–24 years | 220 | 2930 | 4260 | 3018 | 3243 | 707 | 4285 | 648 | 19,311 |

| 25–34 years | 217 | 2960 | 3240 | 4700 | 2839 | 370 | 4595 | 610 | 19,531 |

| 35–44 years | 982 | 8295 | 9356 | 23,019 | 11,513 | 922 | 10,122 | 2175 | 66,384 |

| 45–54 years | 2749 | 15,461 | 17,012 | 42,291 | 30,141 | 1447 | 18,794 | 4466 | 132,361 |

| 55–64 years | 1129 | 4596 | 4853 | 19,189 | 11,470 | 350 | 6516 | 1548 | 49,651 |

| 65 years and over | 9477 | 25,567 | 31,829 | 114,139 | 91,242 | 2132 | 35,104 | 9467 | 318,957 |

| Total (inflation adjusted) | 14,775 | 59,809 | 70,550 | 206,357 | 150,448 | 5927 | 79,416 | 18,914 | 606,196 |

| Domain 6 | Domain 9 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age group | Diabetes | CVD | Mental Disorder | CKD | Diabetes | CVD | Mental Disorder | CKD |

| 20–24 years | 9536 | 22,804 | 31,788 | 17,399 | 3149 | 7531 | 10,497 | 5746 |

| 25–34 years | 2707 | 9326 | 6796 | 6710 | 2707 | 9326 | 6796 | 6710 |

| 35–44 years | 15,615 | 111,973 | 44,709 | 55,648 | 7702 | 55,232 | 22,053 | 27,449 |

| 45–54 years | 21,068 | 285,080 | 47,475 | 416,764 | 14,961 | 202,443 | 33,713 | 295,956 |

| 55–64 years | 11,218 | 258,025 | 16,136 | 340,744 | 4207 | 96,759 | 6051 | 127,779 |

| 65 years and over | 6299 | 550,962 | 10,311 | 1,061,391 | 15,599 | 1,364,430 | 25,535 | 2,628,482 |

| Total (inflation adjusted) | 66,444 | 1,238,170 | 157,215 | 1,898,656 | 48,326 | 1,735,721 | 104,645 | 3,092,121 |

References

- Delaney, L.J. Patient-centred care as an approach to improving health care in Australia. Collegian 2018, 25, 119–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vat, L.E.; Ryan, D.; Etchegary, H. Recruiting patients as partners in health research: A qualitative descriptive study. Res. Involv. Engagem. 2017, 3, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altin, S.V.; Stock, S. The impact of health literacy, patient-centered communication and shared decision-making on patients’ satisfaction with care received in German primary care practices. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2016, 16, 450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. Health Literacy: Taking Action to Improve Safety and Quality; Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care: Sydney, Australia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Mackey, L.M.; Doody, C.; Werner, E.L.; Fullen, B. Self-management skills in chronic disease management: What role does health literacy have? Med. Decis. Mak. 2016, 36, 741–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berkman, N.D.; Sheridan, S.L.; Donahue, K.E.; Halpern, D.J.; Crotty, K. Low health literacy and health outcomes: An updated systematic review. Ann. Intern. Med. 2011, 155, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kickbusch, I. Health literacy: An essential skill for the twenty-first century. Health Educ. 2008, 108, 101–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stormacq, C.; Van den Broucke, S.; Wosinski, J. Does health literacy mediate the relationship between socioeconomic status and health disparities? Integrative review. Health Promot. Int. 2019, 34, e1–e17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paterick, T.E.; Patel, N.; Tajik, A.J.; Chandrasekaran, K. Improving health outcomes through patient education and partnerships with patients. Proc. (Bayl. Univ. Med. Cent.) 2017, 30, 112–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olesen, K.; Reynheim, A.L.F.; Joensen, L.; Ridderstråle, M.; Kayser, L.; Maindal, H.T.; Osborne, R.H.; Skinner, T.; Willaing, I. Higher health literacy is associated with better glycemic control in adults with type 1 diabetes: A cohort study among 1399 Danes. BMJ Open Diabetes Res. Care 2017, 5, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.G.; Jackson, S.E.; Kobayashi, L.C.; Steptoe, A. Social isolation, health literacy, and mortality risk: Findings from the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. Health Psychol. 2018, 37, 160–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tormey, L.K.; Reich, J.; Chen, Y.S.; Singh, A.; Lipkin-Moore, Z.; Yu, A.; Weinberg, J.; Farraye, F.A.; Paasche-Orlow, M.K. Limited health literacy is associated with worse patient-reported outcomes in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2019, 25, 204–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panagioti, M.; Skevington, S.M.; Hann, M.; Howells, K.; Blakemore, A.; Reeves, D.; Bower, P. Effect of health literacy on the quality of life of older patients with long-term conditions: A large cohort study in UK general practice. Qual. Life Res. 2018, 27, 1257–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-Chica, D.A.; Mnisi, Z.; Avery, J.; Duszynski, K.; Doust, J.; Tideman, P.; Murphy, A.; Burgess, J.; Beilby, J.; Stocks, N. Effect of health literacy on quality of life amongst patients with ischaemic heart disease in Australian general practice. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0151079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeWalt, D.A.; Berkman, N.D.; Sheridan, S.; Lohr, K.N.; Pignone, M.P. Literacy and health outcomes: A systematic review of the literature. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2004, 19, 1228–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turkoglu, A.R.; Demirci, H.; Coban, S.; Guzelsoy, M.; Toprak, E.; Aydos, M.M.; Ture, D.A.; Ustundag, Y. Evaluation of the relationship between compliance with the follow-up and treatment protocol and health literacy in bladder tumor patients. Aging Male 2019, 22, 266–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oscalices, M.I.L.; Okuno, M.F.P.; Lopes, M.C.B.T.; Batista, R.E.A.; Campanharo, C.R.V. Health literacy and adherence to treatment of patients with heart failure. Rev. Esc. Enferm. USP 2019, 53, e03447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, M.; Luke, J.; Downey, B.; Crengle, S.; Kelaher, M.; Reid, S.; Smylie, J. Health literacy: Health professionals’ understandings and their perceptions of barriers that Indigenous patients encounter. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2014, 14, 614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Adult Literacy and Life Skills Survey 2006; ABS Publication 4228.0; Australian Bureau of Statistics: Canberra, Australia, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. National Health Survey: Health Literacy, 2018; ABS Publication; Australian Bureau of Statistics: Canberra, Australia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Household Use of Information Technology, Australia, 2016-17 Quality Declaration; ABS Publication 8146.0; Australian Bureau of Statistics: Canberra, Australia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, C.; Dunn, M. Health literacy and the Internet: A study on the readability of Australian online health information. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2015, 39, 309–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdullah, A.; Liew, S.M.; Salim, H.; Ng, C.J.; Chinna, K. Prevalence of limited health literacy among patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0216402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geboers, B.; Reijneveld, S.A.; Jansen, C.J.; de Winter, A.F. Health literacy is associated with health behaviors and social factors among older adults: Results from the LifeLines Cohort Study. J. Health Commun. 2016, 21, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vernon, J.A.; Trujillo, A.; Rosenbaum, S.R.; DeBuono, B. Low Health Literacy: Implications for National Health Policy. Available online: https://publichealth.gwu.edu/departments/healthpolicy/CHPR/downloads/LowHealthLiteracyReport10_4_07.pdf (accessed on 19 January 2021).

- Eichler, K.; Wieser, S.; Brügger, U. The costs of limited health literacy: A systematic review. Int. J. Public Health 2009, 54, 313–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. National Health Survey: First Results 2017-18; ABS Publications; Australian Bureau of Statistics: Canberra, Australia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Blacktown City Council. Transforming Blacktown. Annual Report 2018/19. Available online: https://www.blacktown.nsw.gov.au/files/assets/public/2018-19-annual-report.pdf (accessed on 1 February 2021).

- Blacktown City Council. Social Profile 2020. Available online: https://www.blacktown.nsw.gov.au/files/assets/public/community/social-profile/social-profile-2020.pdf (accessed on 1 February 2021).

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Blacktown-2016 Census QuickStats; ABS Publications; Australian Bureau of Statistics: Canberra, Australia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Centre for Epidemiology and Evidence. HealthStats NSW, 2018–2019. 2018. Available online: http://www.healthstats.nsw.gov.au/ (accessed on 26 February 2021).

- Public Health Information Development Unit (PHIDU). Social Health Atlases. Torrens University Australia. Available online: https://phidu.torrens.edu.au/social-health-atlases (accessed on 1 February 2021).

- Osborne, R.H.; Batterham, R.W.; Elsworth, G.R.; Hawkins, M.; Buchbinder, R. The grounded psychometric development and initial validation of the Health Literacy Questionnaire (HLQ). BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bo, A.; Friis, K.; Osborne, R.H.; Maindal, H.T. National indicators of health literacy: Ability to understand health information and to engage actively with healthcare providers-a population-based survey among Danish adults. BMC Public Health 2014, 14, 1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batterham, R.W.; Buchbinder, R.; Beauchamp, A.; Dodson, S.; Elsworth, G.R.; Osborne, R.H. The OPtimising HEalth LIterAcy (Ophelia) process: Study protocol for using health literacy profiling and community engagement to create and implement health reform. BMC Public Health 2014, 14, 694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leslie, C.J.; Hawkins, M.; Smith, D.L. Using the Health Literacy Questionnaire (HLQ) with Providers in the Early Intervention Setting: A Qualitative Validity Testing Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banbury, A.; Nancarrow, S.; Dart, J.; Gray, L.; Dodson, S.; Osborne, R.; Parkinson, L. Adding value to remote monitoring: Co-design of a health literacy intervention for older people with chronic disease delivered by telehealth-The telehealth literacy project. Patient Educ. Couns. 2020, 103, 597–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, M.; Gill, S.D.; Batterham, R.; Elsworth, G.R.; Osborne, R.H. The Health Literacy Questionnaire (HLQ) at the patient-clinician interface: A qualitative study of what patients and clinicians mean by their HLQ scores. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2017, 17, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beauchamp, A.; Buchbinder, R.; Dodson, S.; Batterham, R.W.; Elsworth, G.R.; McPhee, C.; Sparkes, L.; Hawkins, M.; Osborne, R.H. Distribution of health literacy strengths and weaknesses across socio-demographic groups: A cross-sectional survey using the Health Literacy Questionnaire (HLQ). BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maindal, H.T.; Kayser, L.; Norgaard, O.; Bo, A.; Elsworth, G.R.; Osborne, R.H. Cultural adaptation and validation of the Health Literacy Questionnaire (HLQ): Robust nine-dimension Danish language confirmatory factor model. SpringerPlus 2016, 5, 1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolarcik, P.; Cepova, E.; Geckova, A.M.; Elsworth, G.R.; Batterham, R.W.; Osborne, R.H. Structural properties and psychometric improvements of the health literacy questionnaire in a Slovak population. Int. J. Public Health 2017, 62, 591–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muscat, D.M.; Song, W.; Cvejic, E.; Ting, J.H.C.; Medlin, J.; Nutbeam, D. The Impact of the Chronic Disease Self-Management Program on Health Literacy: A Pre-Post Study Using a Multi-Dimensional Health Literacy Instrument. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friis, K.; Lasgaard, M.; Pedersen, M.H.; Duncan, P.; Maindal, H.T. Health literacy, multimorbidity, and patient-perceived treatment burden in individuals with cardiovascular disease. A Danish population-based study. Patient Educ. Couns. 2019, 102, 1932–1938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. 2011 Census Data; ABS Publications; Australian Bureau of Statistics: Canberra, Australia, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. 2016 Census Data; ABS Publications; Australian Bureau of Statistics: Canberra, Australia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Friedland, R. New estimates of the high costs of inadequate health literacy. In Proceedings of the Pfizer Conference “Promoting Health Literacy: A Call to Action; Pfizer, Inc.: Washington, DC, USA, 1998; pp. 6–10. [Google Scholar]

- Finlay, S.; Megetto, E.; Robinson, A.; Davis, C. Health literacy education for rural health professionals: Shifting perspectives. Aust. Health Rev. 2019, 43, 404–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Western Sydney Local Health District. Workforce Strategic Framework 2015–2020. Available online: https://www.wslhd.health.nsw.gov.au/ArticleDocuments/1336/WSLHD%20Workforce%20Strategic%20Framework%202015%20-%202020%20v18.pdf.aspx (accessed on 1 February 2021).

- Roche, M.A.; Duffield, C.M.; Homer, C.; Buchan, J.; Dimitrelis, S. The rate and cost of nurse turnover in Australia. Collegian 2015, 22, 353–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet. Best Practice Regulation Guidance Note Value of Statistical Life. Available online: https://www.pmc.gov.au/sites/default/files/publications/Value_of_Statistical_Life_guidance_note.pdf (accessed on 1 February 2021).

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Australian Burden of Disease Study: Impact and Causes of Illness and Death in Australia 2015. Available online: https://www.aihw.gov.au/getmedia/c076f42f-61ea-4348-9c0a-d996353e838f/aihw-bod-22.pdf.aspx?inline=true (accessed on 1 February 2021).

- Rickwood, D.J.; Deane, F.P.; Wilson, C.J. When and how do young people seek professional help for mental health problems? Med. J. Aust. 2007, 187, S35–S39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McPhail, S.M. Multimorbidity in chronic disease: Impact on health care resources and costs. Risk Manag. Healthc. Policy 2016, 9, 143–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forman, D.E.; Maurer, M.S.; Boyd, C.; Brindis, R.; Salive, M.E.; Horne, F.M.; Bell, S.P.; Fulmer, T.; Reuben, D.B.; Zieman, S. Multimorbidity in older adults with cardiovascular disease. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2018, 71, 2149–2161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhry, F.R.; Ming, L.C.; Munawar, K.; Zaidi, S.T.R.; Patel, R.P.; Khan, T.M.; Elmer, S. Health literacy studies conducted in Australia: A scoping review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Health Expenditure Australia 2018-19; AIHW: Canberra, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss, B.D.; Palmer, R. Relationship Between Health Care Costs and Very Low Literacy Skills in a Medically Needy and Indigent Medicaid Population. J. Am. Board Fam. Pract. 2004, 17, 44–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howard, D.H.; Gazmararian, J.; Parker, R.M. The impact of low health literacy on the medical costs of Medicare managed care enrollees. Am. J. Med. 2005, 118, 371–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, L.M.; Thompson, V.T.; Wilkinson, J.D. Caregiver health literacy and the use of child health services. Pediatrics 2007, 119, e86–e92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haun, J.N.; Patel, N.R.; French, D.D.; Campbell, R.R.; Bradham, D.D.; Lapcevic, W.A. Association between health literacy and medical care costs in an integrated healthcare system: A regional population based study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2015, 15, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Age Groups | Total Population 2020 (n = 258,223) | LHL Population (Domain 6) (n = 53,451) | % of LHL (Domain 6) | LHL Population (Domain 9) (n = 35,667) | % of LHL (Domain 9) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20–24 years | 24,368 | 12,050 | 49.45 | 3979 | 16.33 |

| 25–34 years | 56,171 | 2663 | 4.74 | 2663 | 4.74 |

| 35–44 years | 55,807 | 13,667 | 24.49 | 6741 | 12.08 |

| 45–54 years | 44,218 | 14,888 | 33.67 | 10,573 | 23.91 |

| 55–64 years | 36,522 | 6428 | 17.60 | 2410 | 6.6 |

| ≥65 years | 41,137 | 3756 | 9.13 | 9301 | 22.61 |

| Prevalence of LHL | 20.70 | 13.81 |

| Type of Chronic Disease Group | Direct Health Care Cost ($) | Direct Health Care Cost (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Cardiovascular disorders | 1,680,869 | 18.3 |

| Musculoskeletal disorder | 1,886,681 | 20.6 |

| Mental illness | 2,269,347 | 24.8 |

| Cancer | 1,298,083 | 14.2 |

| Chronic Kidney Disease | 665,277 | 7.3 |

| Respiratory disorders | 705,970 | 7.7 |

| Diabetes | 660,182 | 7.2 |

| Preventive care (sub-total) | 952,366 (10.4%) | |

| Tertiary care (sub-total) | 8,214,043 (89.6%) | |

| Total | 9,166,409 | 100.0 |

| Area of Service | Direct Health Care Cost ($) | Direct Health Care Cost (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Allied health and other services | 481,270 | 5.3 |

| Diagnostic services | 647,041 | 7.1 |

| General Practitioner | 952,366 | 10.4 |

| Pharmaceutical benefits scheme | 1,879,884 | 20.5 |

| Public hospital admitted patient | 3,263,931 | 35.6 |

| Public hospital emergency department | 401,874 | 4.4 |

| Public hospital outpatient | 970,820 | 10.6 |

| Specialist services | 569,221 | 6.2 |

| Total | 9,166,407 | 100.0 |

| Age Group | Direct Health Care Cost ($) | Direct Health Care Cost (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 20–24 years | 1,003,541 | 10.9 |

| 25–34 years | 278,482 | 3.0 |

| 35–44 years | 1,858,506 | 20.3 |

| 45–54 years | 2,609,297 | 28.5 |

| 55–64 years | 1,634,683 | 17.8 |

| 65 years and over | 1,781,899 | 19.4 |

| Total | 9,166,408 | 100.0 |

| Type of Chronic Disease Group | Direct Health Care Cost ($) | Direct Health Care Cost (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Cardiovascular disorders | 1,866,019 | 22.2 |

| Musculoskeletal disorders | 1,680,558 | 20.0 |

| Mental illness | 1,563,722 | 18.6 |

| Cancer | 1,337,973 | 15.9 |

| Chronic Kidney Disease | 661,653 | 7.9 |

| Respiratory disorders | 689,221 | 8.2 |

| Diabetes | 606,196 | 7.2 |

| Preventive care (sub-total) | 768,906 (9.1%) | |

| Tertiary care (sub-total) | 7,636,435 (90.9%) | |

| Total | 8,405,342 | 100.0 |

| Area of Service | Direct Health Care Cost ($) | Direct Health Care Cost (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Allied health and other services | 329,940 | 4.3 |

| Diagnostic services | 535,870 | 7.0 |

| General Practitioner | 768,906 | 10.1 |

| Pharmaceutical benefits scheme | 1,819,236 | 23.8 |

| Public hospital admitted patient | 3,272,324 | 42.9 |

| Public hospital emergency department | 341,529 | 4.5 |

| Public hospital outpatient | 840,620 | 11.0 |

| Specialist services | 496,915 | 6.5 |

| Total | 8,405,342 | 100.0 |

| Age Groups | Direct Health Care Cost ($) | Direct Health Care Cost (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 20–24 years | 331,401 | 3.9 |

| 25–34 years | 278,482 | 3.3 |

| 35–44 years | 916,731 | 10.9 |

| 45–54 years | 1,852,934 | 22.0 |

| 55–64 years | 613,006 | 7.3 |

| 65 years and over | 4,412,787 | 52.5 |

| Total | 8,405,342 | 100.0 |

| Type of Agent | Type of Cost | Missed Weeks Due to Sickness | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Week | 10% of Weeks in a Year | ||

| Employer | Absenteeism cost | 281,421 | 1,467,329 |

| Presenteeism cost | 1,845,233 | ||

| Total | 2,126,653 | 3,312,561 | |

| Individual | Absenteeism cost | 56,777 | 296,037 |

| Opportunity cost of time due to transportation | 30,363 | ||

| Carers | Carer’s cost | 188,552 | 983,110 |

| Government | Lost tax revenue-employer (absenteeism) | 84,426 | 440,199 |

| Lost tax revenue-employer (presenteeism) | 553,570 | ||

| Lost tax revenue-employer (total) | 637,996 | 993,768 | |

| Lost tax revenue-employee(absenteeism) | 17,033 | 88,811 | |

| Lost tax revenue-carer (absenteeism) | 56,566 | 294,933 | |

| Total | 711,595 | 1,377,513 | |

| Total Indirect cost | 3,113,940 | 5,999,584 | |

| Age Groups | Cancer and Other Neoplasms | Cardiovascular Diseases | Endocrine Disorders | Kidney and Urinary Diseases | Mental Illness and Substance Abuse Disorders | Musculoskeletal Conditions | Respiratory Diseases |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20–24 years | 2.95 | 1.59 | 0.26 | 0 | 0.21 | 0 | 0.46 |

| 25–34 years | 13.06 | 7.17 | 0.85 | 0.53 | 0.89 | 0.39 | 0.9 |

| 35–44 years | 37.66 | 20.7 | 1.93 | 1.73 | 1.18 | 0.69 | 2.01 |

| 45–54 years | 72.95 | 35.93 | 3.47 | 2.56 | 2.28 | 1.06 | 5.55 |

| 55–64 years | 125.11 | 49.48 | 5.35 | 4.65 | 1.55 | 1.73 | 11.73 |

| 65–74 years | 139.05 | 62.78 | 6.57 | 5.95 | 1.36 | 2.2 | 23.75 |

| 75–84 years | 76.01 | 58.65 | 5.83 | 6.38 | 0.96 | 1.89 | 18.39 |

| 85 years and over | 26.16 | 52.78 | 3.33 | 4.56 | 0.71 | 1.48 | 9.28 |

| Extra YLL for all chronic diseases | 492.95 | 289.08 | 27.59 | 26.35 | 9.15 | 9.45 | 72.07 |

| Extra YLL value (2020 $) for all chronic diseases | 104,632,769 | 61,360,061 | 5,856,250 | 5,593,916 | 1,941,598 | 2,004,835 | 15,297,799 |

| Extra YLL value (2020 $) for all chronic diseases and age-groups | 196,687,229 | ||||||

| 20–24 years | 2.33 | 1.38 | 0.82 | 0.09 | 31.71 | 9.39 | 6.12 |

| 25–34 years | 10.29 | 5.97 | 2.63 | 0.64 | 77.38 | 30.28 | 13.43 |

| 35–44 years | 26.19 | 15.01 | 4.78 | 1.43 | 65.29 | 39.57 | 15.19 |

| 45–54 years | 43.22 | 22.74 | 6.47 | 1.93 | 37.07 | 40.96 | 14.39 |

| 55–64 years | 63.69 | 29.37 | 8.75 | 2.99 | 16.59 | 43.88 | 16.23 |

| 65–74 years | 65.89 | 36.72 | 8.46 | 3.7 | 7.09 | 36.11 | 21.3 |

| 75–84 years | 30.98 | 28.56 | 4.02 | 3.21 | 1.9 | 13.18 | 12.62 |

| 85 years and over | 9.56 | 21.07 | 1.49 | 1.88 | 0.68 | 3.31 | 4.94 |

| Extra YLD for all chronic diseases | 252.17 | 160.82 | 37.41 | 15.88 | 237.72 | 216.68 | 104.23 |

| Extra YLD value (2020 $) for all chronic diseases | 53,524,081 | 34,136,295 | 7,940,133 | 3,370,362 | 50,458,071 | 45,992,590 | 22,122,575 |

| Extra YLD value (2020 $) for all chronic diseases and age-groups | 217,544,106 | ||||||

| 20–24 years | 5.28 | 2.97 | 1.07 | 0.09 | 31.92 | 9.39 | 6.58 |

| 25–34 years | 23.35 | 13.14 | 3.47 | 1.18 | 78.27 | 30.67 | 14.33 |

| 35–44 years | 63.84 | 35.72 | 6.71 | 3.16 | 66.48 | 40.26 | 17.21 |

| 45–54 years | 116.17 | 58.67 | 9.94 | 4.5 | 39.36 | 42.03 | 19.94 |

| 55–64 years | 188.81 | 78.85 | 14.1 | 7.64 | 18.14 | 45.61 | 27.96 |

| 65–74 years | 204.94 | 99.5 | 15.03 | 9.65 | 8.46 | 38.31 | 45.06 |

| 75–84 years | 106.99 | 87.21 | 9.85 | 9.59 | 2.86 | 15.07 | 31 |

| 85 years and over | 35.72 | 73.85 | 4.82 | 6.43 | 1.39 | 4.79 | 14.22 |

| Extra DALY for all chronic diseases | 745.12 | 449.91 | 65 | 42.23 | 246.87 | 226.13 | 176.3 |

| Extra DALY value (2020 $) for all chronic diseases | 158,156,850 | 95,496,356 | 13,796,382 | 8,964,278 | 52,399,669 | 47,997,425 | 37,420,374 |

| Extra DALY value (2020 $) for all chronic diseases and age-groups | 414,231,335 | ||||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tannous, W.K.; Ahmed, M.U.; John, J.R.; Reece, G.; Ahlenstiel, G. Estimating the Economic Burden of Low Health Literacy in the Blacktown Community in Sydney, Australia: A Population-Based Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2303. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18052303

Tannous WK, Ahmed MU, John JR, Reece G, Ahlenstiel G. Estimating the Economic Burden of Low Health Literacy in the Blacktown Community in Sydney, Australia: A Population-Based Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(5):2303. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18052303

Chicago/Turabian StyleTannous, Wadad Kathy, Moin Uddin Ahmed, James Rufus John, Graham Reece, and Golo Ahlenstiel. 2021. "Estimating the Economic Burden of Low Health Literacy in the Blacktown Community in Sydney, Australia: A Population-Based Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 5: 2303. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18052303

APA StyleTannous, W. K., Ahmed, M. U., John, J. R., Reece, G., & Ahlenstiel, G. (2021). Estimating the Economic Burden of Low Health Literacy in the Blacktown Community in Sydney, Australia: A Population-Based Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(5), 2303. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18052303