Cybervictimization and Adolescent Internet Addiction: A Moderated Mediation Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Rejection Sensitivity as a Mediator

1.2. Parent–Adolescent Communication as a Moderator

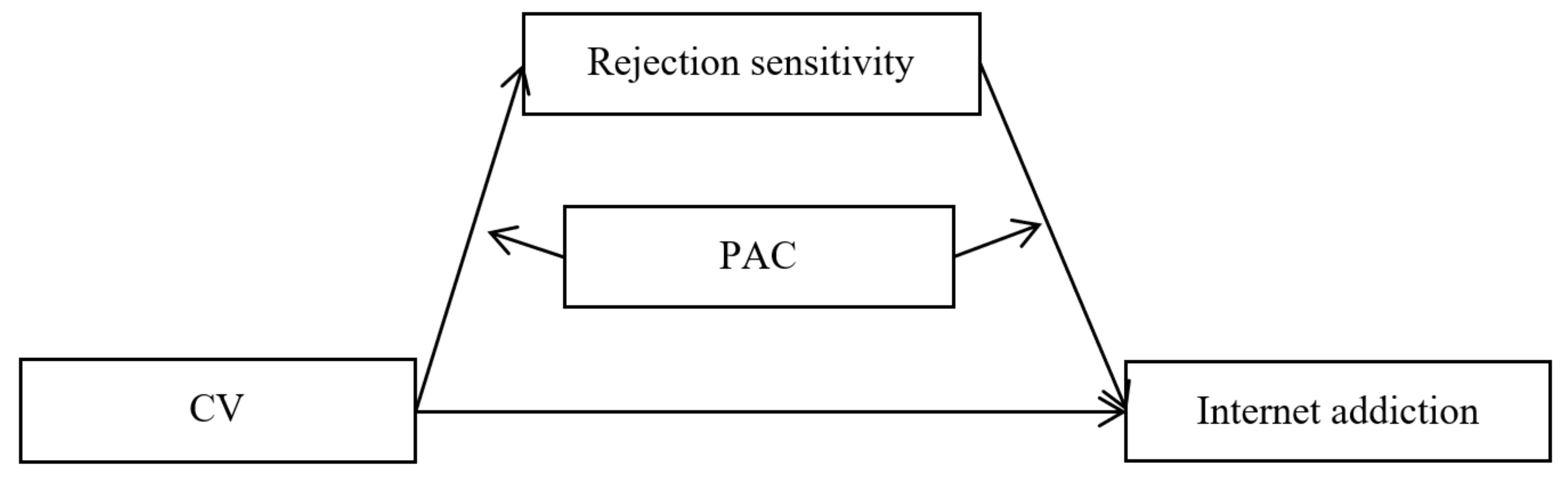

1.3. The Present Study

- (a)

- Does rejection sensitivity mediate the relationship between cybervictimization and adolescent Internet addiction?

- (b)

- Does parent–adolescent communication act as a buffer for the mediating effect of rejection sensitivity in the relationship between cybervictimization and Internet addiction? (Figure 1).

2. Method

2.1. Participant

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Cybervictimization

2.2.2. Internet Addiction

2.2.3. Rejection Sensitivity

2.2.4. Parent–Adolescent Communication

2.2.5. Control Variables

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Preliminary Analyses

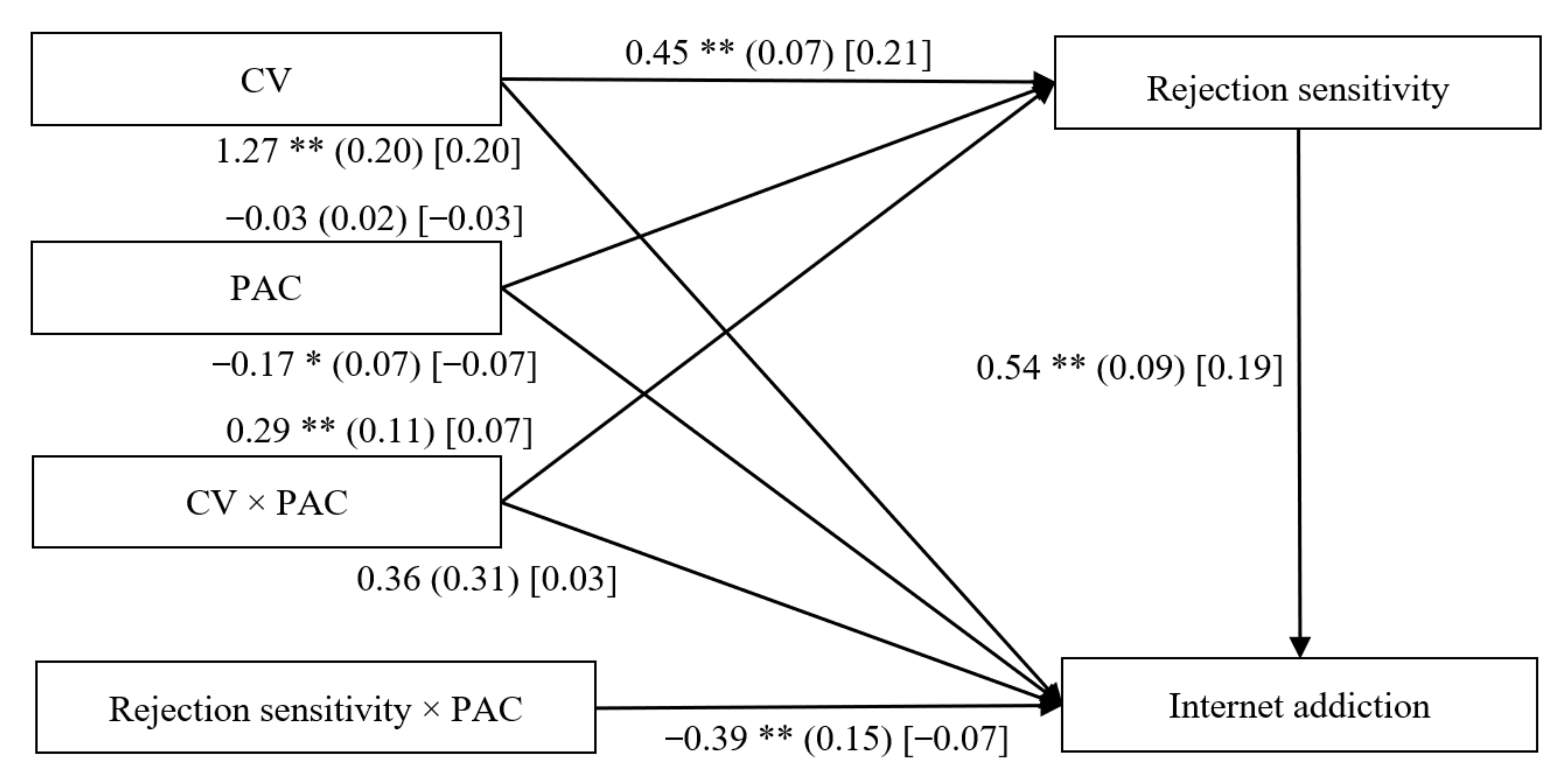

3.2. Testing for Mediation Effect of Rejection Sensitivity

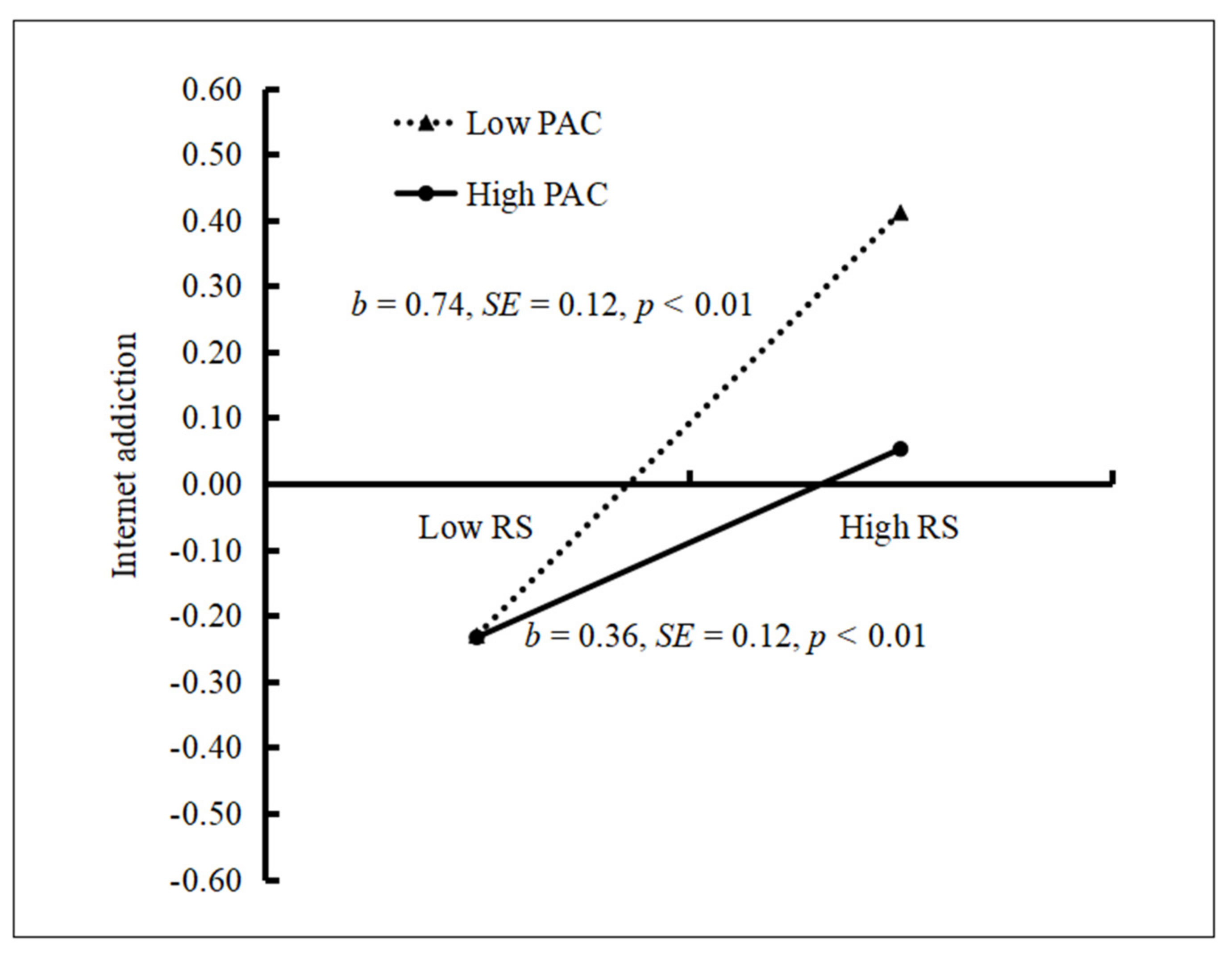

3.3. Testing for Moderated Mediation

4. Discussion

4.1. The Mediating Role of Rejective Sensitivity

4.2. The Moderating Role of Parent–Adolescent Communication

4.3. Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Implications for Practice

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Block, J.J. Issues for DSM-V: Internet addiction. Am. J. Psychiatry 2008, 16, 306–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Lei, L.; Yu, G.; Li, B. Social networking sites addiction and materialism among Chinese adolescents: A moderated mediation model involving depression and need to belong. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 3373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- China Internet Network Information Center. “The 47th Statistical Report on Internet Development in China”. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2021-02/03/content_5584518.htm (accessed on 3 February 2020).

- Demir, Y.; Kutlu, M. Relationships among Internet addiction, academic motivation, academic procrastination and school attachment in adolescents. Int. Online J. Educ. Sci. 2018, 10, 315–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostak, M.A.; Dindar, İ.; Dinçkol, R.Z. Loneliness, depression, social support levels, and other factors involving the Internet use of high school students in Turkey. Int. J. Ment. Health Addic. 2019, 17, 1521–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, B.; Li, D.; Li, X.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Sun, W.; Wang, Y. Perceived school climate and problematic Internet use among adolescents: Mediating roles of school belonging and depressive symptoms. Addict. Behav. 2020, 110, 106501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athanasiou, K.; Melegkovits, E.; Andrie, E.K.; Magoulas, C.; Tzavara, C.K.; Richardson, C.; Tsitsika, A.K. Cross-national aspects of cyberbullying victimization among 14-17-year-old adolescents across seven European countries. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.K.; Chen, L.M. Cyberbullying among adolescents in Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Mainland China: A cross-national study in Chinese societies. Asia Pac. J. Soc. Work 2020, 30, 227–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simsek, N.; Sahin, D.; Evli, M. Internet addiction, cyberbullying, and victimization relationship in adolescents: A sample from Turkey. J. Addict. Nurs. 2019, 30, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.; Liu, Z.; Yuan, G. Cybervictimization and problematic Internet use among Chinese adolescents: Longitudinal mediation through mindfulness and depression. J. Health Psychol. 2020, 1, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khantzian, E.J. The self-medication hypothesis of substance use disorders: A reconsideration and recent applications. Harv. Rev. Psychiatry 1997, 4, 231–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gámez-Guadix, M.; Gini, G.; Calvete, E. Stability of Cybervictimization among adolescents: Prevalence and association with bully–victim status and psychosocial adjustment. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 53, 140–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Liu, Q.; Yu, S. Child neglect, psychological abuse and smartphone addiction among Chinese adolescents: The roles of emotional intelligence and coping style. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2019, 90, 74–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samur, D.; Tops, M.; Schlinkert, C.; Quirin, M.; Cuijpers, P.; Koole, S.L. Four decades of research on alexithymia: Moving toward clinical applications. Front. Psychol. 2013, 4, 861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downey, G.; Feldman, S.I. Implications of rejection sensitivity for intimate relationships. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1996, 70, 1327–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, S.; Ayduk, O.; Downey, G. The Role of Rejection Sensitivity in People’s Relationships with Significant Others and Valued Social Groups. In Interpersonal Rejection; Leary, M., Ed.; Oxford University: Oxford, UK, 2001; pp. 281–289. ISBN 0195130146. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, C.A.; Doorley, J.D.; Esposito-Smythers, C. Interpersonal rejection sensitivity mediates the associations between peer victimization and two high-risk outcomes. Clin. Child. Psychol. Psychiatry 2017, 22, 649–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, X.; Fu, R.; Ooi, L.L.; Coplan, R.J.; Zheng, Q.; Deng, X. Relations between different components of rejection sensitivity and adjustment in Chinese children. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 2020, 67, 101119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molinari, L.; Grazia, V.; Corsano, P. School relations and solitude in early adolescence: A mediation model involving rejection sensitivity. J. Early Adolesc. 2020, 40, 426–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Monteagudo, M.C.; Delgado, B.; Inglés, C.J.; Escortell, R. Cyberbullying and social anxiety: A latent class analysis among Spanish adolescents. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2020, 17, 406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olenik-Shemesh, D.; Heiman, T. Cyberbullying victimization in adolescents as related to body esteem, social support, and social self-efficacy. J. Genet. Psychol. 2017, 178, 28–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, S.L.; Mitchell, S.M.; Roush, J.F.; La Rosa, N.L.; Cukrowicz, K.C. Rejection sensitivity and suicide ideation among psychiatric inpatients: An integration of two theoretical models. Psychiatry Res. 2019, 272, 54–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molavi, P.; Mikaeili, N.; Ghaseminejad, M.A.; Kazemi, Z.; Pourdonya, M. Social anxiety and benign and toxic online self-disclosures: An investigation into the role of rejection sensitivity, self-regulation, and Internet addiction in college students. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2018, 206, 598–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farahani, H.A.; Aghamohamadi, S.; Kazemi, Z.; Bakhtiarvand, F.; Ansari, M. Examining the relationship between sensitivity to rejection and using Facebook in university students. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2011, 28, 807–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caplan, S.E. Relations among loneliness, social anxiety, and problematic Internet use. Cyberpsychol. Behav. 2007, 10, 234–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinstein, A.; Abu, H.B.; Timor, A.; Mama, Y. Delay discounting, risk-taking, and rejection sensitivity among individuals with Internet and video gaming disorders. J. Behav. Addict. 2016, 5, 674–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Withers, M.C.; Mcwey, L.M.; Lucier-Greer, M. Parent-adolescent relationship factors and adolescent outcomes among high-risk families. Fam. Relat. 2016, 65, 661–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerman, P.; Constantine, N.A. Demographic and psychological predictors of parent-adolescent communication about sex: A representative state-wide analysis. J. Youth Adolesc. 2010, 39, 1164–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.Y.; Chun, J.S. Structural model of parent-adolescent communication, depression-anxiety, emotion-dysregulation, and Internet addiction among adolescents. J. Youth Stud. 2016, 18, 159–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Lin, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Zhang, W. Perceived parent–adolescent communication and pathological Internet use among Chinese adolescents: A moderated mediation model. J. Child. Fam. Stud. 2019, 28, 1571–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellfeldt, K.; López-Romero, L.; Andershed, H. Cyberbullying and psychological well-being in young adolescence: The potential protective mediation effects of social support from family, friends, and teachers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2020, 17, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, P.; Irons, C.; Olsen, K.; Gilbert, J.; McEwan, K. Interpersonal sensitivities: Their links to mood, anger and gender. Psychol. Psychother. 2006, 79, 37–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stadler, C.; Feifel, J.; Rohrmann, S.; Vermeiren, R.; Poustka, F. Peer victimization and mental health problems in adolescents: Are parental and school support protective? Child. Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2010, 41, 371–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, C.A.; Mirman, J.H.; García-España, J.F.; Thiel, M.C.F.; Friedrich, E.; Salek, E.C.; Jaccard, J. Effect of primary care parent-targeted interventions on parent-adolescent communication about sexual behavior and alcohol use: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw. Open. 2019, 2, 199535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodge, T.; Clarke, P. Influence of parent–adolescent communication about anabolic steroids on adolescent athletes’ willingness to try performance-enhancing substances. Subst. Use Misuse 2015, 50, 1307–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Eghrari, H.; Patrick, B.C.; Leone, D.R. Facilitating internalization: The self-determination theory perspective. J. Pers. 1994, 62, 119–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özdemir, Y. Cyber victimization and adolescent self-esteem: The role of communication with parents. J. Soc. Psychol. 2014, 17, 255–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocayoruk, E. The perception of parents and well-being of adolescents: Link with basic psychological need satisfaction. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 46, 3624–3628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mclachlan, J.; Zimmer-Gembeck, M.J.; Mcgregor, L. Rejection sensitivity in childhood and early adolescence: Peer rejection and protective effects of parents and friends. J. Relatsh. Res. 2010, 1, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ledwell, M.; King, V. Bullying and internalizing problems: Gender differences and the buffering role of parental communication. J. Fam. Issue 2015, 36, 543–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chng, G.S.; Li, D.; Liau, A.K.; Khoo, A. Moderating effects of the family environment for parental mediation and pathological Internet use in youths. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2015, 18, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdur-Baker, O. Cyberbullying and its correlation to traditional bullying, gender and frequent and risky usage of Internet-mediated communication tools. New Media Soc. 2010, 12, 109–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pontes, H.M.; Griffiths, M.D. Measuring DSM-5 Internet gaming disorder: Development and validation of a short psychometric scale. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 45, 137–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X. The Correlation Study of Rejection Sensitivity. Master’s Thesis, Jiangxi Normal University, Nanchang, China, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Su, S.; Li, X.; Lin, D.; Xu, X.; Zhu, M. Psychological adjustment among left-behind children in rural China: The role of parental migration and parent-child communication. Child. Care Health Dev. 2013, 39, 162–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.S.; Tseng, P.T.; Lin, P.Y.; Chen, T.Y.; Stubbs, B.; Carvalho, A.F. Internet addiction and its relationship with suicidal behaviors: A meta-analysis of multinational observational studies. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2018, 79, 17r11761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spada, M.M. An overview of problematic internet use. Addict. Behav. 2014, 39, 3–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Yu, C.; Zhang, W.; Bao, Z.; Jiang, Y.; Chen, Y. Peer victimization, deviant peer affiliation and impulsivity: Predicting adolescent problem behaviors. Child. Abuse Negl. 2016, 58, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cyders, M.A.; Littlefield, A.K.; Coffey, S.; Karyadi, K.A. Examination of a short English version of the UPPS-P impulsive behavior scale. Addict. Behav. 2014, 39, 1372–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthén, L.K.; Muthén, B.O. Mplus User’s Guide; Muthén, L.K., Muthén, B.O., Eds.; Muthén&Muthén: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis. J. Educ. Meas. 2013, 51, 335–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. A power primer. Psychol. Bull. 1992, 112, 155–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kretschmer, T. What explains correlates of peer victimization? A systematic review of mediating factors. Adolesc. Res. Rev. 2016, 1, 341–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Z.; Wang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Yang, L. Chinese university students’ loneliness and generalized pathological Internet use: A longitudinal cross-lagged analysis. Soc. Behav. Pers. 2018, 46, 861–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavell, C.H.; Zimmer-Gembeck, M.J.; Farrell, L.J.; Webb, H. Victimization, social anxiety, and body dysmorphic concerns: Appearance-based rejection sensitivity as a mediator. Body Image 2014, 11, 391–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinberg, L.; Silverberg, S.B. The vicissitudes of autonomy in early adolescence. Child. Dev. 1986, 57, 841–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, B.; Li, D.; Jia, J.; Liu, Y.; Sun, W.; Wang, Y. Peer victimization and problematic Internet use in adolescents: The mediating role of deviant peer affiliation and the moderating role of family functioning. Addict. Behav. 2019, 96, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Li, X.; Tian, L.; Huebner, E.S. Longitudinal association between low self-esteem and depression in early adolescents: The role of rejection sensitivity and loneliness. Psychol. Psychother. 2020, 93, 54–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 485 | 48.20 |

| Female | 521 | 51.80 |

| Age | ||

| 12–12.99 years | 423 | 42.05% |

| 13–13.99 years | 433 | 43.04% |

| 14–14.99 years | 150 | 14.91% |

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.Gender | 1.00 | ||||||

| 2.Age | 0.06 * | 1.00 | |||||

| 3.Impulsivity | 0.00 | −0.08 * | 1.00 | ||||

| 4.CV | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.21 ** | 1.00 | |||

| 5.PAC | −0.02 | −0.14 ** | −0.29 ** | −0.14 ** | 1.00 | ||

| 6.RS | −0.20 ** | 0.01 | 0.31 ** | 0.23 ** | −0.13 ** | 1.00 | |

| 7.IA | 0.07 * | 0.02 | 0.35 ** | 0.30 ** | −0.20 ** | 0.29 ** | 1.00 |

| α | — | — | 0.82 | 0.82 | 0.68 | 0.86 | 0.74 |

| Mean | — | 13.16 | 2.12 | 1.13 | 2.26 | 3.04 | 1.18 |

| SD | — | 0.67 | 0.40 | 0.20 | 0.53 | 0.43 | 1.25 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xin, M.; Chen, P.; Liang, Q.; Yu, C.; Zhen, S.; Zhang, W. Cybervictimization and Adolescent Internet Addiction: A Moderated Mediation Model. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2427. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18052427

Xin M, Chen P, Liang Q, Yu C, Zhen S, Zhang W. Cybervictimization and Adolescent Internet Addiction: A Moderated Mediation Model. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(5):2427. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18052427

Chicago/Turabian StyleXin, Mucheng, Pei Chen, Qiao Liang, Chengfu Yu, Shuangju Zhen, and Wei Zhang. 2021. "Cybervictimization and Adolescent Internet Addiction: A Moderated Mediation Model" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 5: 2427. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18052427

APA StyleXin, M., Chen, P., Liang, Q., Yu, C., Zhen, S., & Zhang, W. (2021). Cybervictimization and Adolescent Internet Addiction: A Moderated Mediation Model. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(5), 2427. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18052427