Abstract

Mental health issues in family businesses and business families have been studied in multiple disciplines within the past three decades. This article systematically reviews 51 articles on mental health issues in family businesses and business families, published in a wide variety of psychology, entrepreneurship, and management journals. Based on a systematic review of extant literature, this article first provides an overview of the state of the art, followed by specific suggestions on novel research questions, theoretical frameworks and study design. This way, the review systematizes evidence on known antecedents and consequences of mental health issues in family businesses and business families, but also reveals overlooked and undertheorized drivers and outcomes. The review reveals major gaps in our knowledge that hinder a valid understanding of mental health in the specific context of family businesses and business families, and articulates specific research questions that could be tackled by future research among management as well as mental health scholars. Finally, we point to the relevance of this study for policy makers, family business advisors, therapists and managers.

1. Introduction

Mental health and psychosocial wellbeing were included as an integral part of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in 2015 for the first time, thereby recognizing it as a global development priority [1]. Mental health issues are affecting individuals and families worldwide, but also the businesses they operate in [2]. This is especially the case for family businesses (hereafter: FB), the most ubiquitous form of organization worldwide [3]. The intertwining and interdependence of the family and the business system, which is unique and inherent to family businesses, creates both competitive resources as well as challenges and disadvantages for the involved business [4], their involved families [5] and their non-family stakeholders [6]. This intertwining of the family and the business sub-system confronts business families (hereafter: BF) and their advisors with unique challenges when it comes to their psychological and emotional health [7] with for example spill-over and the risk for aggravation of tensions from one sub-system to another. Mental health issues are thus likely to affect FBs and their owning business families in multiple ways, both positive and negative [2].

The closely intertwined family and business system in FBs [8,9] results in interactions and exchanges of resources across the family and business system which are crucial for sustaining the FB, especially during times of disruption [10] such as during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic and its aftermath in which the wellbeing of family and non-family members has been put under pressure [11].

In this paper we systematically review the literature on drivers and outcomes of mental health issues within family businesses and business families. Literature on this important topic is widely dispersed across various disciplines. Therefore, we are convinced that it is time to take stock of the current literature and to give a broad and complete overview of what we know on mental health issues in family businesses and business families, which will form a good basis to elaborate future studies in this area. For the purpose of this review, we consider articles dealing with “all” types of family businesses, meaning that they can be characterized by family involvement in various ways (e.g., management, ownership or governance), and that they can be small or large; public or private. Similar to [12], we do not consider single owner-managed firms with no other relatives involved, as family firms.

For the purpose of this review, we employ the World Health Organization (WHO) definition of mental health. This indicates that mental health is “a state of well-being in which an individual realizes his or her own abilities, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively and is able to make a contribution to his or her community”. The important implication of this definition is that mental health is more than the mere absence of mental disorders and disabilities. By employing this definition, we expand the literature review of [2], who focus on mental disorders of individual relatives in family businesses. Our broader scope of mental health is in line with the paradigm shift in the field of psychology, which traditionally focused on negative aspects of human experiences such as mental disorders and their treatment, towards the emerging field of positive psychology [13] which focuses on factors that maintain and promote mental health in respect to happiness, engagement, and self-actualization [14,15].

Given that studies on mental health in FB and/or BF are widely dispersed across various disciplines and given the specific challenges that the FB context poses on understanding and managing mental health in FB and BF, we want to contribute to a more integrated understanding of mental health in the FB context. We will do this by taking stock of the literature so far and by pointing to relevant future research areas. Hence, the central aim of this systematic literature review is to draw attention to mental health issues as a research area that could benefit from being positioned more centrally and in a multidisciplinary way in management, family business, psychology and public health literature. To this end, we assess the literature of drivers and outcomes of mental health issues in the family business system (i.e., at the individual-family- and business-level), to provide guidance to policy makers and practitioners and to inspire future research on this topic. The objective of this review is, therefore, to specifically address the following three research questions: what is the current state of the literature on mental health issues in family businesses and business families? (RQ1); what are the implications for future research in this domain? (RQ2); and what are the implications for policy makers, family business advisors, therapists and owners? (RQ3) In an attempt to answer these research questions, we present the state of the art on mental health issues in the context of family businesses and business families. We first identify gaps in the current literature, where we focus on the subtopics that have been addressed, the study context, methods and theories applied. We then articulate avenues for future research in this area, with the aim to advance the knowledge on mental health issues in family businesses as well as business families.

The remainder of this article is structured as follows. In the first section, our review method is presented in detail. Next, we discuss the study selection and present the general characteristics of the studies that were retained for the review. Finally, gaps in literature are identified and potentially fruitful avenues for future research (in terms of relevant research questions, theoretical frameworks, and research methods) are articulated as well as insights and recommendations for policy makers and family business advisors and mental healthcare providers.

2. Methods

2.1. Review Method

For this article, we follow the systematic review method that has been used in previous management research, which is based on the process used in medical science and healthcare [16,17]. This method allows researchers to map and assess the relevant research and to articulate research questions which will advance the knowledge base. A rigorous review method is essential to be able to provide insights and guidance for scholars, as well as for practitioners and policy makers [16]. In light of the exploratory nature of our research question, the heterogeneity in our data (i.e., studies published in many different disciplines), and the fact that this is a less mature field of research, a systematic review is the most simple and straightforward method as it can point to missing data and call for empirical research at the right point in time [18]. Essentially, it is our goal to identify a comprehensive sample of journal articles that (empirically or conceptually) discuss mental health issues in family businesses and business families.

The first choice we made, was to only include peer-reviewed journal articles, thereby excluding unpublished work, books and book chapters. This restriction can be expected to enhance quality control as most refereed journals have strict requirements for publication [19]. The second choice was to use the following databases: ISI Web of Science Core Collection, EBSCO Host Business Source Complete and PubMed. Because these databases search in multiple disciplines at once, they can be considered to be appropriate and efficient for our purposes. The third step was to select a sample of articles from the millions of articles compiled in these databases. Article titles and/or abstracts had to include terms referring to both mental health issues and family businesses. We identified the following keywords to capture the ‘family entity’: “family firm*” OR “family-owned” OR “family-controlled” OR “family-managed” OR “family compan*” OR “family business*”OR “business famil*”. These terms were combined with keywords used to capture the ‘mental health entity’, which, according to our definition employed (mental health as a hybrid of absence of a mental disorder and presence of well-being) includes aspects related to mental health, absence of mental health, or coping: “mental” OR “health” OR “well-being” OR “wellness” OR “self-efficacy” OR “autonom*” OR “self-actuali*” OR “psychological capital” OR “resilien*” OR “disorder” OR “dysle*”OR “autis*” OR “addict*” OR “burnout” OR “stress” OR “strain” OR “coach*” OR “therap*”. We searched for a combination of a mental health entity and a family entity in the title and/or the abstract of articles that were published in print or online until July 2020. This step led to a total of 845 articles being identified through database searching. In order to ensure no relevant research articles were missed, we manually checked major outlets for family business research individually by checking the indexes. Through this step, an additional six articles were identified.

2.2. Articles Selection

For a journal article to be retained in the analyses, we decided it had to either conceptually advance our understanding of mental health issues in family businesses or business families, or to empirically test propositions regarding mental health in a family business or a business family context. Thus, in the next step, the relevance was checked by the two authors who independently read all titles and abstracts. All abstracts that were indicated as ‘irrelevant to the review’ were excluded. Disagreements on article selection were resolved by consensus. Then, all remaining articles were downloaded and the full text was read by both authors independently. Several articles were excluded due to non-compliance with the established inclusion criteria. Examples were: no considerable conceptual or empirical understanding of mental health issues in family businesses or business families, or the use of one of the search terms in a different context (e.g., “…the authors stress the importance of” or “financial well-being” or “…are engaged in earnings management). In this review, we define a family business as a business where at least two family members are involved in ownership, management or governance. Hence, we exclude studies on single business owners-entrepreneurs with no other relatives involved.

2.3. Data Extraction and Synthesis

After all relevant articles had been selected, both authors independently coded the articles following a predefined coding scheme in Excel. Disagreements on coding were resolved by consensus. The following aspects were coded for each paper: year, author, outlet, mental health topic, focus (family/business/individual), research question, core theoretical concepts or frameworks, research method, sample, variables included (dependent, independent, moderator, mediator), findings related to mental health in the family business or business family.

3. Results

3.1. Results of Literature Search

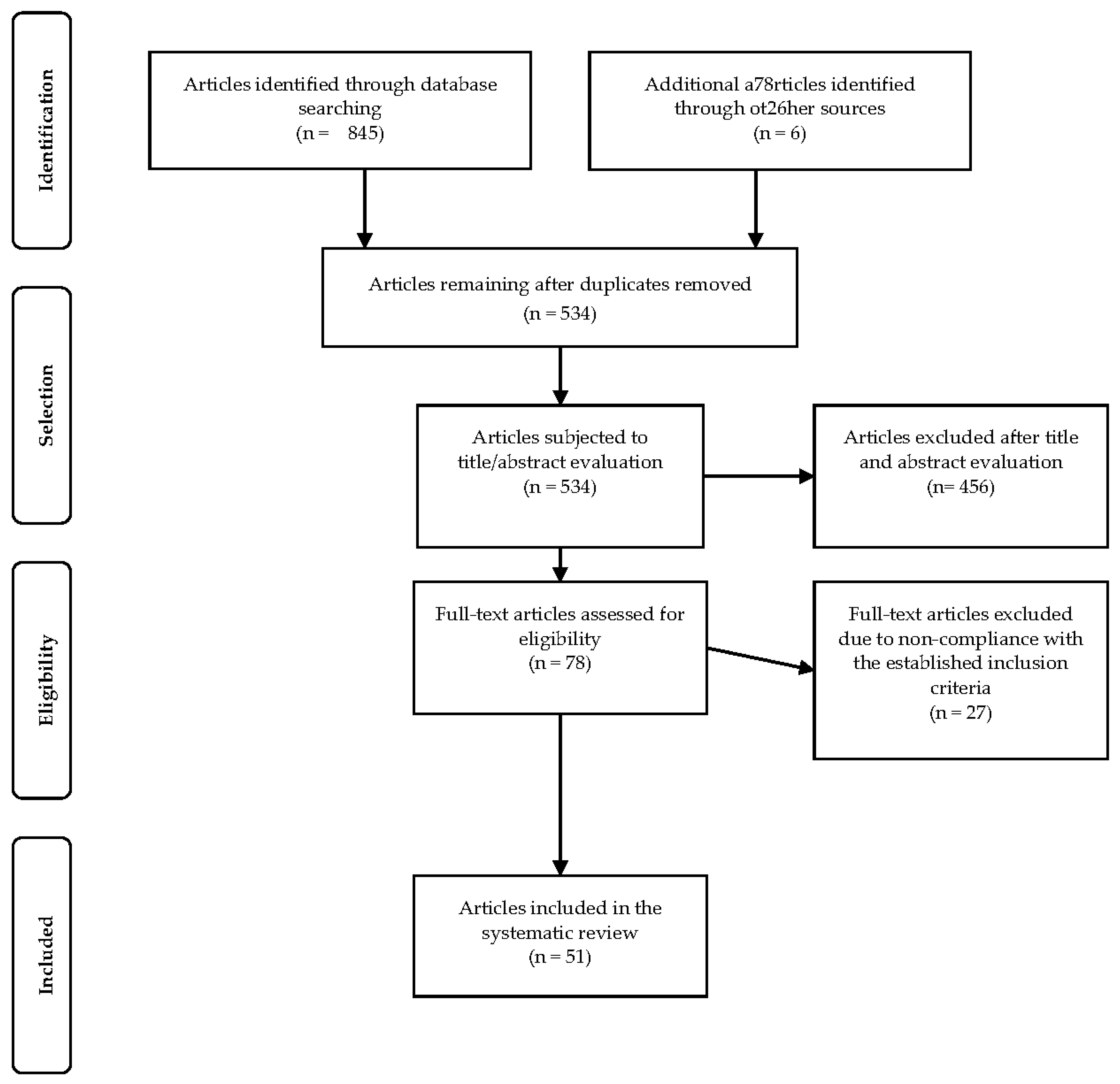

A total of 845 papers were obtained through database searching, and an additional six articles were identified through other sources. After removing duplicates, 534 articles remained. After evaluating the titles and abstracts, 456 articles were removed from the sample. Of the 78 full-text articles that were assessed for their eligibility, 51 papers were retained for our final sample. See Figure 1 for a visual representation of our literature search in a Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram [20].

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram of the search and screening.

3.2. Study Characteristics and Synthesis of Results

The first study that was published on mental health issues in family businesses and business families dates from 1989. This indicates that this research field is less mature, but it is also not surprising, since academic interest in family businesses only emerged in the 1980s [21] and has increased rapidly in the past two decades [22].

Academic interest in the mental health topic in family businesses and business families has been increasing rapidly with 73% of all papers (38 papers) in our sample being published after 2010. The articles in our review have been published in a variety of disciplines including entrepreneurship, psychology, management and family studies.

The mental health topics that have received most attention in scholarly research are wellbeing, family- and self-efficacy, therapy and resilience. The studies in our sample investigated mental health topics at a variety of levels. For example, resilience was studied from an individual family member perspective (e.g., [23]), from a family-level perspective (e.g., [24]), from an organizational, family business, perspective (e.g., [25]) or from a combination of the aforementioned levels. A wide variety of theoretical frameworks were used to develop hypotheses, with the most frequently used theories being: family systems theory (6 papers), self-determination theory (2 papers), work-family interface (4 papers), sustainable family business theory (2 papers). The research method that was used most often, was quantitative in nature (e.g., regression, structural equation modelling, correlations) (21 papers). Fifteen papers in our sample were conceptual, or theoretical, in nature. Another six papers were primarily based on consulting experiences and often provided fictionalized examples. Only 8 papers used a qualitative research strategy through interviews and/or case studies. When quantitative or qualitative data were analysed from a specific country, they came primarily from the USA (19 papers), followed by China (3 papers) and Austria (2), Belgium (2) and Canada (2).

The theoretical foundations that have been used in our sample come from various disciplines, such as psychology (e.g., self-determination theory, psychological capital); family science (e.g., Bowen’s family systems theory, circumplex model) and management (e.g., resource based view, stewardship theory). There is no theory that stands out in terms of number of times used, as we have identified 41 different theoretical frameworks in our sample. Eleven papers in our sample did not rely on a clear theoretical framework.

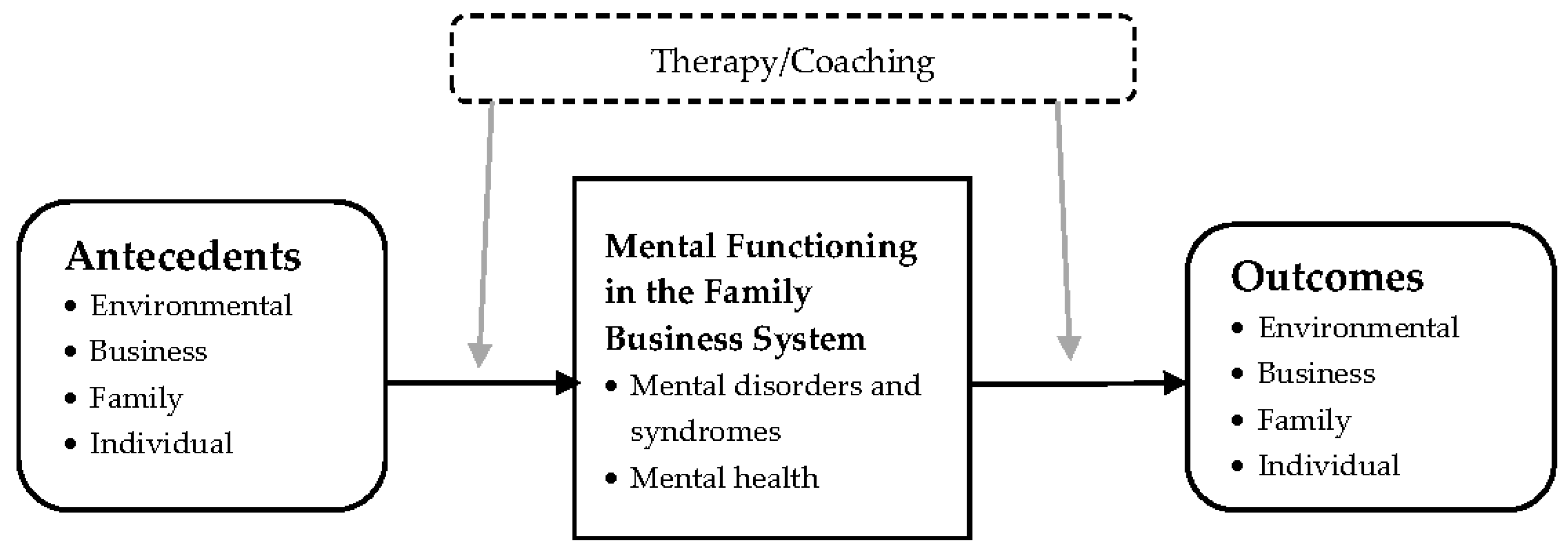

Table 1 gives an overview of the literature that has been reviewed in this article. More specifically, we summarized the findings of our sample studies according to their focus on one (or more) of the following aspects of mental functioning in the family business system: mental disorders and syndromes or mental health; and its respective drivers and outcomes, as illustrated in Figure 2.

Table 1.

Overview of extant research on mental health in family businesses and business families.

Figure 2.

Mental health issues researched in family businesses and business families. (Note. Family Business System = Family, Business, Individual.).

4. Discussion and Suggestions for Future Research

The aim of this review was to draw attention to mental health issues as a research area that would benefit from being positioned more centrally and in a more multi-disciplinary way in management, family business, psychology and public health literature. By means of this literature review we thus aim to open up and start a new conversation which might inspire and guide future relevant research and practice for studying and dealing in a more adequate way with mental health in the FB context. Based on our systematic literature review we identified three major gaps in our knowledge that hinder a valid understanding of mental health in the specific context of FB and BF: a lack of understanding of the effect of the business on the family and its family members’ ill-being and well-being (Research Gap 1); a need for adopting a multi-level perspective on mental health in FB (Research Gap 2); and a lack of an open-systems perspective incorporating the environmental level in studies of mental health in FB (Research Gap 3). In this section we formulate fruitful research avenues on the topic of mental health in FB and BF based on these detected gaps and provide a number of sample research questions which could fill in these gaps in our knowledge.

4.1. Research Gaps and Sample Research Questions

By transferring the positive psychology-based view of mental health to the FB context, our literature review also encompasses studies that explored factors, practices and conditions that enabled FB ownership to yield positive effects on individual and familial well-being. So far, most literature focused on the effects of family ownership on business performance and hardly touched upon the effect a business can have on the owning or running family involved in it [5,45] (i.e., first research gap). For the studies that did focus on the impact of the business on the family, the predominant focus was on ill-being of the family (e.g., tensions, quarrels, ruptures) due to the business involvement [60]. Role conflicts due to dual roles as member of the family and member of the business seem the dominant antecedent of this ill-being in this family business literature stream [57]. Only few studies investigated the benefits of being involved or having work experience in the family-owned business for individual relatives. The main outcomes point to higher reported parental support and less addiction for adolescents involved in the FB, e.g., [39,40]. Hence, we lack knowledge on how being involved in the family business can affect the mental health (both ill-being and well-being) of individual family members and of the family system.

For studying the effects of the business on the mental health at ‘individual level’, the self determination theory might be a promising theoretical framework for future research. A FB with clear values and norms supporting FB participation may be a double-edged sword for individual family members to reconcile the need for autonomy (e.g., freedom of career choice) with the need for relatedness (e.g., normative commitment as a drive for joining the FB, [71]). Tapping into self determination theory literature, some studies suggest that given the social context, individuals may forgo some autonomy needs in exchange for relatedness (e.g., [72]) as being put forward by [31] for the FB context. This brings us to two sample research questions:

RQ 1: What are the optimal levels of basic psychological needs to foster psychological well-being of individual family members in the FB context and which practices are effective to reach or restore this optimal interplay?

RQ 2: How can a FB reach an optimal interplay between autonomy and relatedness to ensure psychological well-being of individual family members (e.g., successors)?

For studying the effects of the business on the mental health at ‘family level’, ‘family self-efficacy’ (e.g., [34]) might be a promising concept as a theoretical base for future research. In particular, we detected the need for empirical support for its key dimensions and for insights in developmental experiences and tools to cultivate this family self-efficacy. Self-efficacy is an important antecedent of well-being in mental health literature in general [73]. In a FB context, taking into account the multi-level interplay of mechanisms contributing to mental health (i.e., research gap 2), we stress the importance of studying not only individual family members’ self-efficacy but also collective efficacy among involved family members–family members’ shared beliefs in its family’s capabilities as a group–to ensure the necessary encouragement and support among family members [57]. The family support was already put forward in entrepreneurial literature as a driver for mental wellbeing of entrepreneurs, often female entrepreneurs (e.g., [74]). Within FB literature so far the emphasis has been put on the importance of entrepreneurial self-efficacy among successors which might be beneficial for the FB (e.g., [75]). The sustainable success of a FB depends on both the success of the business system and the family system, i.e., the central tenet of Sustainable Family Business Theory (e.g., [24]). Therefore, it might be important to gain more insight in how to cultivate and groom domain-specific self-efficacy at individual level (e.g., entrepreneurial self-efficacy), at business level (e.g., industry knowledge) as well as at family level (i.e., family self-efficacy) and in how these all interrelate. The explorative qualitative study of [34] already mentioned the need of the development of a domain-specific FB self-efficacy scale in 2007. They pointed to important dimensions in this FB self-efficacy scale, such as having the capability and confidence in the competencies to maintain good relationships with the incumbent and other involved family members in the FB, maintain good relationships with other business stakeholders, have business-specific knowledge, but acknowledged that there was no insight in how these skills and confidence in these skills could be fostered in the specific FB context. Based on our systematic literature review, we have to conclude that more than a decade later the literature still falls short in having a valid and reliable FB self-efficacy scale and in having insights in how to develop these domain-specific efficacy dimensions. Hence, useful research questions to focus on might be:

RQ 3a: Which dimensions (i.e., items comprising individual, family and business level) belong to a domain-specific FB self-efficacy scale?

RQ 3b: How can each of these dimensions be cultivated most effectively in the FB context (e.g., role of incumbent, of mentors, of coaching, of training programs)?

Taking into account the need for more multi-level studies in the FB context (i.e., research gap 2), a related research question that deserves our attention is:

RQ 4. To what extent can collective family-efficacy moderate the effect of individual family members’ self-efficacy on the mental wellbeing of individual family members, the family’s well-being and the performance of the business?

In fact, self-efficacy is part of the broader concept of ‘psychological capital’, a central tenet in positive psychology [76]. Ref. [55] were the first to introduce the concept of Organizational Psychological Capital, as a potential leading but yet overlooked concept in FB studies. So far, the four dimensions of OCP–organizational hope, optimism, resilience and efficacy have been addressed in mainly conceptual papers in the specific FB context (e.g., [59]), with a few exceptions that provided empirical testing (e.g., [44] for effect of family business resiliency on role interference). Hence we need more empirical underpinning of the premises and optimal level of ‘organizational psychological capital’ in a FB context. In addition, there is the need for a distinction in this group-level approach of this construct between family as a group and the organization (comprising of family and non-family employees) as a group. Furthermore, we have only a limited understanding of how each of the four dimensions of this psychological capital can be developed at family and at business/organizational level beyond individual level. For example, the recently introduced concept of ‘family resiliency’ (i.e., family’s belief in their ability to discover solutions to manage challenges, [77]) in family business literature by e.g., [44]) as the family’s adjustment strategies and coping capacity to respond to stressful events) is distinct from organizational resiliency [25]. Family and organizational resiliency can have meaningful interrelations, and can be fostered via other tools in a FB context, nonetheless it is important to assess them each separately to find rigorous relations with outcome variables. This brings us to the challenge of bringing this psychological capital to higher levels with rigorous conceptual and operational definitions [78]. The FB context might provide a fruitful context to contribute to this multi-level approach with the following sample research questions:

RQ 5a How is each dimension of psychological capital– measured at individual, family and organizational level—affecting individual, family and business outcomes?

RQ 5b Which theoretical mechanisms can guide meaningful cross-level effects?

Previous research has yet demonstrated that psychological capital is trainable (e.g., [76]). Based on these insights, we formulate the following sample research question:

RQ 5c How can organizational psychological capital be fostered in the specific context of a FB for the family and for the business group-level?

Overall, we notice in our systematic literature review that studying the effect of the business on the involved family is scarce, but slightly on the rise. This valuable future research avenue may further benefit from integrating insights and theories from family science literature (e.g., the Circumplex Model of Family Systems, Family Fundamental Interpersonal Relations Orientation, or FIRO, Theory) [5,49]) to enrich FB literature (e.g., improved insights in how to reach sustainable family business success) and family therapy literature with this unique but omnipresent context of FB among their clients. We notice that there is hardly any empirical evidence on which type of interventions and which type of family business advisors are most effective per type of family business issues and especially business family problems.

Next, none of the studies in our literature review has focused on the environmental level and its interplay with mental health in the family business context (i.e., research gap 3). This gap in literature is a surprise, as yet in 2007 FB scholars explained the need for an open-systems approach as conceptual model to adequately study FB [8]. The recent COVID-19 pandemic has shown that also FB and their business families are severely hit not only business-wise but also in terms of mental health [79]. COVID-19 and its aftermath have put considerable strain on the physical and emotional wellbeing of family and non-family members, bringing tensions to the surface (e.g., on dividend pay-outs, on decisions on business model changes or on sticking to tradition), engendering negative emotions (e.g., grief, frustration, anxiety, fear) which might undermine the clarity of thought of key decision-makers in the FB [11]. Notwithstanding this strain, FBs seem to focus on employee well-being during this crisis [79]. Individual family members’ sacrifices for securing the continuity of the FB (e.g., missing dividend payouts), seemed to be facilitated if the family benefits from alignment and cohesion, which is enabled by good communication practices. This challenge brings us to the following important research question:

RQ 6: What is the impact of COVID-19 on the wellbeing of family and nonfamily members in the FB?

With regard to the well-being of employees in a FB context in non-crisis situation, we find mixed evidence. For example, results are contradictory on whether employees in FB versus NFB are more or less victim of workplace bullying [26,28]. We believe that more in-depth insight into which mechanisms are at play due to the involved owning family, might help unraveling these conflicting results. We illustrate this with the interaction between generation at helm and seniority of employees: favoritism might prevail towards employees with higher seniority by the founding FB owners while the opposite might occur with succeeding generations taking over the reins leading to power conflicts and triggering mobbing for this high seniority subgroup. Beyond statistical consensus on the well-being of employees in FB versus NFB settings, insight in the mechanisms at play is needed, as it might enable practitioners and policy makers to set up more effective interventions in these different contexts. This also holds for the processes leading to burn-out in a FB context. It was a surprise that the omnipresent topic of burn-out in mental health and occupational health literature is still untouched in the FB context. In the entrepreneurial context, the need for studying entrepreneurial burn-out and its unique antecedents and outcomes is already detected (e.g., [80]). Also, in the FB context, it is likely that the unfolding of burn-out among involved relatives as well as among non-family employees might be different than in non-FB context due to the higher risk of role conflict. This brings us to the following sample research question:

RQ7 Which antecedents and mechanisms result from the unique involvement of owning families in organizations to affect employee well-being (e.g., bullying, burn-out)?

We want to point to some limitations in our review method. Firstly, we only included published work, which might have prevented us from integrating creative insights which might not have made it to peer-reviewed publication outlets yet. We made this choice to ensure a good quality standard for the studies on which we based our insights in our review. A second limitation has to do with the exclusion of non-English publications. English is the mainstream language for scientific research (on family businesses) so we are confident that the exclusion effect will be limited on the scope of our included studies. We want to add that although U.S. is largely represented in our sampled articles, also other non-English speaking countries were present in our sample like China, Belgium, and Austria. For the time period, we want to emphasize that we did not use a ‘lower limit’ for year of publication and that the most recent year being yet 1989 for mental health in FB is a reflection of the recent nature of the family business field as academic field [21].

4.2. Relevance to Pracitioners: Family Business Advisors and Healthcare Providers

For practitioners it might be useful to explicitly integrate in the family constitution how resiliency will be developed, and at individual, family and family business level. This attention for the different processes at play in building resilience at the different levels is recently put forward in research (e.g., [25]). This way, and adequate family-practice fit can be assured [81]. Such a code of ethics can also avoid deviant behavior of family and non-family employees [32] and as such avoid tensions.

The omnipresent antecedent of role conflicts impacting the family’s and individuals’ well-being and the FB performance can be prevented or mitigated by open communication which can prevent or reconcile unrealistic (dual) role expectations [57]. Ref. [59] found empirical proof for the indirect effect of open communication through a shared vision on the FB on next-generation leadership effectiveness and work engagement, which precludes a better multi-generational survival with respect to a better mental health at work (as work engagement is vital to wellbeing at work according to positive psychology studies, e.g., [82]). Relying on these empirical findings brings us to the advice for practitioners to invest in family meetings where open communication is facilitated or trained. This training in effective communication and conflict resolution skills can reduce stress and facilitate healthier relationships. We would like to re-emphasize the call of ref. [53] to also include extended family members in this training and business family communication. Unfortunately, so far research overlooks in-laws for their effect on the mental health of the business family. Therapists can also benefit from the awareness of stress induced by the business family communication dynamics for in-laws [53]. Therapists or coaches can also benefit from systemic work like the tetralemma for solving problems or dilemmas in business families for example due to the fact that one communicative event might trigger even contradictory reactions in the family and the business system and lead to a seemingly impossible way out to make a ‘right’ decision [48].

The cultivation and stimulation of collective family-efficacy beyond self-efficacy of individual family members is likely to be fruitful to facilitate multi-generational survival [57] where the individual relative, the family and the family business can flourish. This entails that a FB advisor is not only able to provide or recommend individual coaching to foster self-efficacy of individual relatives, but also group coaching to the family group to ensure that the belief in the capabilities of the family as a group is shared and the complementarity is embraced which can serve as a prevention or a healing mechanism against rivalry (e.g., among successors).

Lastly, relying on Sustainable Family Business Theory [10] and on insights from our literature review on therapy and consulting in a FB context, e.g., [30,35,48,50,69], business families need family therapists that are familiar with emotional family dynamics, systemic work, and have affinity with the FB context/literature but equally need business consultants who can focus on business challenges. Who is involved depends on the needs of the FB clients, but an exchange of information, most ideally a collaboration or even an interdisciplinary partnership, between these two streams of advisors might be most beneficial to ensure sustainable family business success.

4.3. Relevance to Policy Makers

Our systematic literature review also brings forward some implications for policy makers. First, it emphasizes the importance of wellbeing strategies for employees in a family business context which take into account the specific nature and challenges of the family business context. Proactive and reactive policies to foster or restore employees’ mental health in family businesses should be aware of the risk of poor communication among business families that spills over to the business and creates stress for non-family employees (e.g., [68]).

Given the interplay at three levels for understanding and intervening adequately in the mental health challenges of family business systems, e.g., [25], we formulate the suggestion for policy makers to create certified programmes for FB advisors that should focus on fostering expertise relating to mental health at all three levels (i.e., individual, family and business) of the family business system. In addition, FB advisors should be made aware of the need to team up with experts in other domains (e.g., family therapists, communication experts) if their knowledge is insufficient for dealing adequately with specific mental health needs at e.g., the family level to build or restore for example family-level efficacy or family-level resiliency. In addition, it might be worth policy makers considering a requirement for a code of conduct or a code of ethics for the discipline of family business advisors. In this code this multi-disciplinary expertise could be central, or at least the deontological duty for teaming up with other experts of other disciplines to adequately deal with mental health needs at all levels of the family business system. In this way policy makers can support and require family business advisors to develop interventions that have the potential to result in sustainable success, hence at all three levels (individual-family and business) and preferably in an integrated way across all three levels.

The inheritance systems of FB legacies have an undeniable influence on sibling rivalry, stress and entrepreneurial spirit (e.g., [70]). Policy makers should, therefore, carefully consider the impact of inheritance policy measures not only on economic development, but equally on family and individual well-being, when (re-)designing business succession or inheritance schemes.

5. Conclusions

In this systematic review, we focused on mental health issues in family businesses and business families. The main incentive for this systematic literature review is the increasing importance of this topic, as well as the multidisciplinary nature of studies in this domain. Literature on this topic is quite fragmented, which restricts scholars’ capacity to effectively integrate the insights into a more comprehensively developed perspective. Developing a state of the art on mental health issues in family businesses and business families allows us, therefore, to structure extant evidence, which enables us to provide relevant findings for practitioners and policy makers and to identify gaps and discuss interesting new research directions which can guide future research in this domain. Overall, we can conclude that the uniqueness of family businesses, being the intertwining of the family and the business system, represents a double-edged sword for business families that strive for mental health at individual, family and business levels. Based on our systematic review of the literature, we identified three major gaps in our knowledge, that hinder a thorough understanding of mental health issues in the specific context of FB and BF: (1) future research might benefit from studying further the impact of being together in a business on the business family. More precisely, more insight is needed in how the well-being of the business family and its individual members can be supported by, for example, exploring tools and testing its effects empirically for building resiliency and domain-specific efficacy at individual, family and business levels. (2) In addition to this multi-level focus, also the interplay between the different levels, i.e., systems, is highly relevant if we want to build a further valid theory on mental health in the family business context (3). Lastly, the environmental level is currently a blind spot in how mental health is studied in a family business context. Our study translates our current knowledge on mental health in the FB context in concrete implications for policy makers, practitioners (advisors and healthcare providers) and researchers.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.M. and D.A.; methodology, A.M. and D.A.; analysis, A.M. and D.A.; writing—original draft preparation, A.M. and D.A.; writing—review and editing, A.M. and D.A.; visualization, A.M. and D.A. Both authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Patel, V.; Saxena, S.; Lund, C.; Thornicroft, G.; Baingana, F.; Bolton, P.; Chisholm, D.; Collins, P.Y.; Cooper, J.L.; Eaton, J. The Lancet Commission on global mental health and sustainable development. Lancet 2018, 392, 1553–1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, D.; Wiklund, J.; Yu, W. Mental Health in the Family Business: A Conceptual Model and a Research Agenda. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2020, 44, 55–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IFERA. Family business dominate. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2003, 16, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Dyer, W.G. Examining the “family effect” on firm performance. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2006, 19, 253–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michael-Tsabari, N.; Lavee, Y. Too close and too rigid: Applying the circumplex model of family systems to first-generation family firms. J. Marital Fam. Ther. 2012, 38, 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellermanns, F.W.; Eddleston, K.A.; Zellweger, T.M. Article commentary: Extending the socioemotional wealth perspective: A look at the dark side. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2012, 36, 1175–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vries, M.F.K.; Carlock, R.; Florent-Treacy, E. Family Business on the Couch; Wiley Online Library: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Pieper, T.M.; Klein, S.B. The bulleye: A systems approach to modeling family firms. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2007, 20, 301–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldrich, H.E.; Cliff, J.E. The pervasive effects of family on entrepreneurship: Toward a family embeddedness perspective. J. Bus. Ventur. 2003, 18, 573–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danes, S.M.; Brewton, K.E. Follow the capital: Benefits of tracking family capital across family and business systems. In Understanding Family Businesses; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; pp. 227–250. [Google Scholar]

- De Massis, A.; Rondi, E. COVID-19 and the future of family business research. J. Manag. Stud. 2020, 57, 1727–1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, D.; Le Breton-Miller, I.; Lester, R.H. Family and lone founder ownership and strategic behaviour: Social context, identity, and institutional logics. J. Manag. Stud. 2011, 48, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seligman, M.E.; Csikszentmihalyi, M. Positive psychology: An introduction. In Flow and the Foundations of Positive Psychology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 279–298. [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson, B. Positivity: Groundbreaking Research to Release Your Inner Optimist and Thrive; Simon and Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Huber, A.; Webb, D.; Höfer, S. The German version of the strengths use scale: The relation of using individual strengths and well-being. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tranfield, D.; Denyer, D.; Smart, P. Towards a methodology for developing evidence-informed management knowledge by means of systematic review. Br. J. Manag. 2003, 14, 207–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, R.J.; Han, S.K. A systematic assessment of the empirical support for transaction cost economics. Strateg. Manag. J. 2004, 25, 39–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petticrew, M.; Roberts, H. Systematic Reviews in the Social Sciences: A Practical Guide; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Light, R.J.; Pillemer, D.B. Summing Up: The Science of Reviewing Research; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; Group, P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bird, B.; Welsch, H.; Astrachan, J.H.; Pistrui, D. Family business research: The evolution of an academic field. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2002, 15, 337–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Short, J.C.; Sharma, P.; Lumpkin, G.T.; Pearson, A.W. Oh, the Places We’ll Go! Reviewing Past, Present, and Future Possibilities in Family Business Research; SAGE Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Santoro, G.; Messeni-Petruzzelli, A.; Del Giudice, M. Searching for resilience: The impact of employee-level and entrepreneur-level resilience on firm performance in small family firms. Small Bus. Econ. 2020, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanson, S.K.; Hessel, H.M.; Danes, S.M. Relational processes in family entrepreneurial culture and resilience across generations. J. Fam. Bus. Strategy 2019, 10, 100263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanson, S.K.; Keplinger, K. The balance that sustains benedictines: Family entrepreneurship across generations. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2020, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baillien, E.; Neyens, I.; De Witte, H. Organizational correlates of workplace bullying in small- and medium-sized enterprises. Int. Small Bus. J. Res. Entrep. 2011, 29, 610–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boles, J.S. Influences of work-family conflict on job satisfaction, life satisfaction and quitting intentions among business owners: The case of family-operated businesses. Fam. Bus. Rev. 1996, 9, 61–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceja, L.; Escartin, J.; Rodriguez-Carballeira, A. Organisational contexts that foster positive behaviour and well-being: A comparison between family-owned firms and non-family businesses. Rev. Psicol. Soc. 2012, 27, 69–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christian-Kliger, P.; Nixon, W.R., Jr. The Mind of the Executive Through the Eyes of Psychoanalytic Partners. Psychoanal. Inq. 2012, 32, 393–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, P.M.; Johnson, K. A perfect fit: Connecting family therapy skills to family business needs. J. Marital Fam. Ther. 2012, 38, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, D.; Peake, W.O. Family Member Well-Being in the Kinship Enterprise: A Self-Determination Perspective. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2018, 42, 340–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, J.T.; Kidwell, R.E.; Eddleston, K.A. Boss and Parent, Employee and Child: Work-Family Roles and Deviant Behavior in the Family Firm. Fam. Relat. 2013, 62, 457–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degadt, J. Business family and family business: Complementary and conflicting values. J. Enterprising Cult. 2003, 11, 379–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeNoble, A.; Ehrlich, S.; Singh, G. Toward the development of a family business self-efficacy scale: A resource-based perspective. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2007, 20, 127–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Distelberg, B.; Castanos, C. Levels of Interventions for MFTs Working with Family Businesses. J. Marital Fam. Ther. 2012, 38, 72–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, P.R.J.M.; Sharma, P.; De Massis, A.; Wright, M.; Scholes, L. Perceived parental behaviors and next-generation engagement in family firms: A social cognitive perspective. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2019, 43, 224–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giesen, C.; Maas, A.; Vriens, M. Stress among farm women: A structural model approach. Behav. Med. 1989, 15, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gudmunson, C.G.; Danes, S.M.; Werbel, J.D.; Loy, J.T.C. Spousal Support and Work-Family Balance in Launching a Family Business. J. Fam. Issues 2009, 30, 1098–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, D.M.; Jarvis, P.A. Adolescent employment and psychosocial outcomes—A comparison of two employment contexts. Youth Soc. 2000, 31, 417–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houshmand, M.; Seidel, M.D.L.; Ma, D.G. The Impact of Adolescent Work in Family Business on Child-Parent Relationships and Psychological Well-Being. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2017, 30, 242–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q.; Schaufeli, W.B. Job insecurity and remuneration in Chinese family-owned business workers. Career Dev. Int. 2011, 16, 6–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutcheson, J.O.; Jaffe, D.; Gilliland, K. Addiction in the family enterprise. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2013, 26, 104–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaffe, D.T. The world of family business consulting. Consult. Manag. 2006, 17, 21. [Google Scholar]

- Jang, J.; Danes, S.M. Role interference in family businesses. Entrep. Res. J. 2013, 3, 367–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, J.E.; Breitkreuz, R.S.; James, A.E. When family members are also business owners: Is entrepreneurship good for families? Fam. Relat. 2013, 62, 472–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karofsky, P.; Millen, R.; Yilmaz, M.R.; Smyrnios, K.X.; Tanewski, G.A.; Romano, C.A. Work-family conflict and emotional well-being in American family businesses. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2001, 14, 313–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaleelee, O. Succession and survival in psychotherapy organizations. J. Anal. Psychol. 2008, 53, 633–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleve, H.; Roth, S.; Kollner, T.; Wetzel, R. The tetralemma of the business family: A systemic approach to business-family dilemmas in research and practice. J. Organ. Chang. Manag. 2020, 33, 433–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, D.A.; Shams, M. Supporting the Family Business: A Coaching Practitioner’s Handbook; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.; Danes, S.M. Uniqueness of family therapists as family business systems consultants: A cross-disciplinary investigation. J. Marital Fam. Ther. 2012, 38, 92–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Sun, J.Y.; Wang, L.; Ke, J. Second-Generation Women Entrepreneurs in Chinese Family-Owned Businesses: Motivations, Challenges, and Opportunities. Adv. Dev. Hum. Resour. 2020, 22, 124–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lumpkin, G.T.; Martin, W.; Vaughn, M. Family orientation: Individual-level influences on family firm outcomes. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2008, 21, 127–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marotzbaden, R.; Mattheis, C. Daughters-In-Law and Stress in 2-Generation Farm Families. Fam. Relat. 1994, 43, 132–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMullen, J.S.; Warnick, B.J. Article commentary: To nurture or groom? The parent–founder succession dilemma. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2015, 39, 1379–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memili, E.; Welsh, D.H.B.; Luthans, F. Going beyond Research on Goal Setting: A Proposed Role for Organizational Psychological Capital of Family Firms. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2013, 37, 1289–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memili, E.; Welsh, D.H.; Kaciak, E. Organizational psychological capital of family franchise firms through the lens of the leader–member exchange theory. J. Leadersh. Organ. Stud. 2014, 21, 200–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memili, E.; Chang, E.P.C.; Kellermanns, F.W.; Welsh, D.H.B. Role conflicts of family members in family firms. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2015, 24, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michael-Tsabari, N.; Houshmand, M.; Strike, V.M.; Treister, D.E. Uncovering Implicit Assumptions: Reviewing the Work–Family Interface in Family Business and Offering Opportunities for Future Research. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2020, 33, 64–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, S.P. Next-generation leadership development in family businesses: The critical roles of shared vision and family climate. Front. Psychol. 2014, 5, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordstrom, O.; Jennings, J.E. Looking in the other direction: An ethnographic analysis of how family businesses can be operated to enhance familial well-being. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2018, 42, 317–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overbeke, K.K.; Bilimoria, D.; Somers, T. Shared vision between fathers and daughters in family businesses: The determining factor that transforms daughters into successors. Front. Psychol. 2015, 6, 625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paucar-Caceres, A.; Hart, D.; Roma i Verges, J.; Sierra-Lozano, D. Applying soft systems methodology to the practice of managing family businesses in Catalonia. Syst. Res. Behav. Sci. 2016, 33, 312–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.; Kallmuenzer, A.; Buhalis, D. Hospitality entrepreneurs managing quality of life and business growth. Curr. Issues Tour. 2019, 22, 2014–2033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, G.N.; Eddleston, K.A. Family Involvement in the Firm, Family-to-Business Support, and Entrepreneurial Outcomes: An Exploration. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2017, 55, 614–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siakas, K.; Vassiliadis, S.; Siakas, E. Family businesses: A diagnosis and self therapy model. Int. J. Entrep. Knowl. 2014, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Smyrnios, K.X.; Romano, C.A.; Tanewski, G.A.; Karofsky, P.I.; Millen, R.; Yilmaz, M.R. Work-family conflict: A study of American and Australian family businesses. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2003, 16, 35–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sprung, J.M.; Jex, S.M. All in the Family: Work-Family Enrichment and Crossover Among Farm Couples. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2017, 22, 218–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stier, S. Wellness in the family business. Fam. Bus. Rev. 1993, 6, 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieszt, A. Application of family therapy in family businesses—A case study research on family business consulting. Soc. Econ. 2017, 39, 213–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, V. Inheritance, Chinese family business and economic development in Hong Kong. J. Enterprising Cult. 2002, 10, 287–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Irving, P.G. Four bases of family business successor commitment: Antecedents and consequences. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2005, 29, 13–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L.; Grolnick, W.S. Autonomy, relatedness, and the self: Their relation to development and psychopathology. Dev. Psychopathol. 1995, 1, 618–655. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Ballesteros, R.; Díez-Nicolás, J.; Caprara, G.V.; Barbaranelli, C.; Bandura, A. Determinants and structural relation of personal efficacy to collective efficacy. Appl. Psychol. 2002, 51, 107–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welsh, D.H.B.; Kaciak, E. Family enrichment and women entrepreneurial success: The mediating effect of family interference. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2019, 15, 1045–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sardeshmukh, S.R.; Corbett, A.C. The duality of internal and external development of successors: Opportunity recognition in family firms. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2011, 24, 111–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthans, F.; Avey, J.B.; Patera, J.L. Experimental analysis of a web-based training intervention to develop positive psychological capital. Acad. Manag. Learn. Educ. 2008, 7, 209–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, J.M. Understanding family resilience. J. Clin. Psychol. 2002, 58, 233–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luthans, F.; Youssef-Morgan, C.M. Psychological capital: An evidence-based positive approach. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2017, 4, 339–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astrachan, C.B. Research Reveals How Business Families Have Coped with COVID-19; FamilyBusiness.org; Entrepreneur & Innovation Exchange: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Shepherd, C.D.; Marchisio, G.; Morrish, S.C.; Deacon, J.H.; Miles, M.P. Entrepreneurial burnout: Exploring antecedents, dimensions and outcomes. J. Res. Mark. Entrep. 2010, 12, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astrachan, C.B.; Astrachan, J.H.; Kotlar, J.; Michiels, A. Addressing the theory-practice divide in family business research: The case of shareholder agreements. J. Fam. Bus. Strategy 2021, 100395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seppälä, P.; Mauno, S.; Feldt, T.; Hakanen, J.; Kinnunen, U.; Tolvanen, A.; Schaufeli, W. The construct validity of the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale: Multisample and longitudinal evidence. J. Happiness Stud. 2009, 10, 459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).