Hospital Climate and Peer Report Intention on Adverse Medical Events: Role of Attribution and Rewards

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Conceptual Background and Research Hypotheses

2.1. Hospital Climate and Peer Report Intention

2.2. Mediating Effect of Individual Attribution Tendency

2.3. Moderating Effect of Reward

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Design

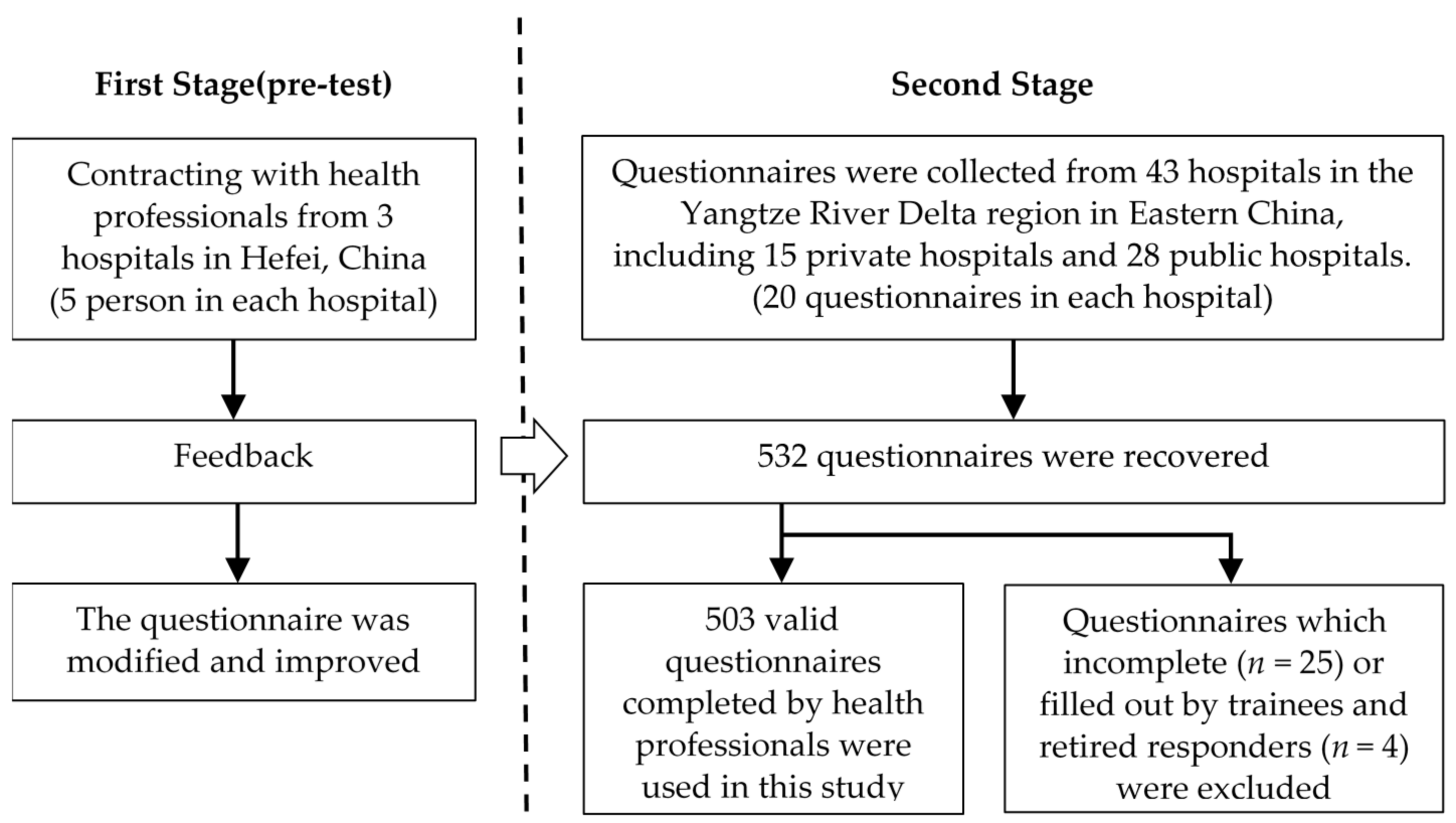

3.2. Data Collection

3.3. Study Participants

3.4. Scale

3.4.1. Measures

3.4.2. Test of Reliability and Validity

3.4.3. Test of Common Method Bias and Multicollinearity

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Data Analysis

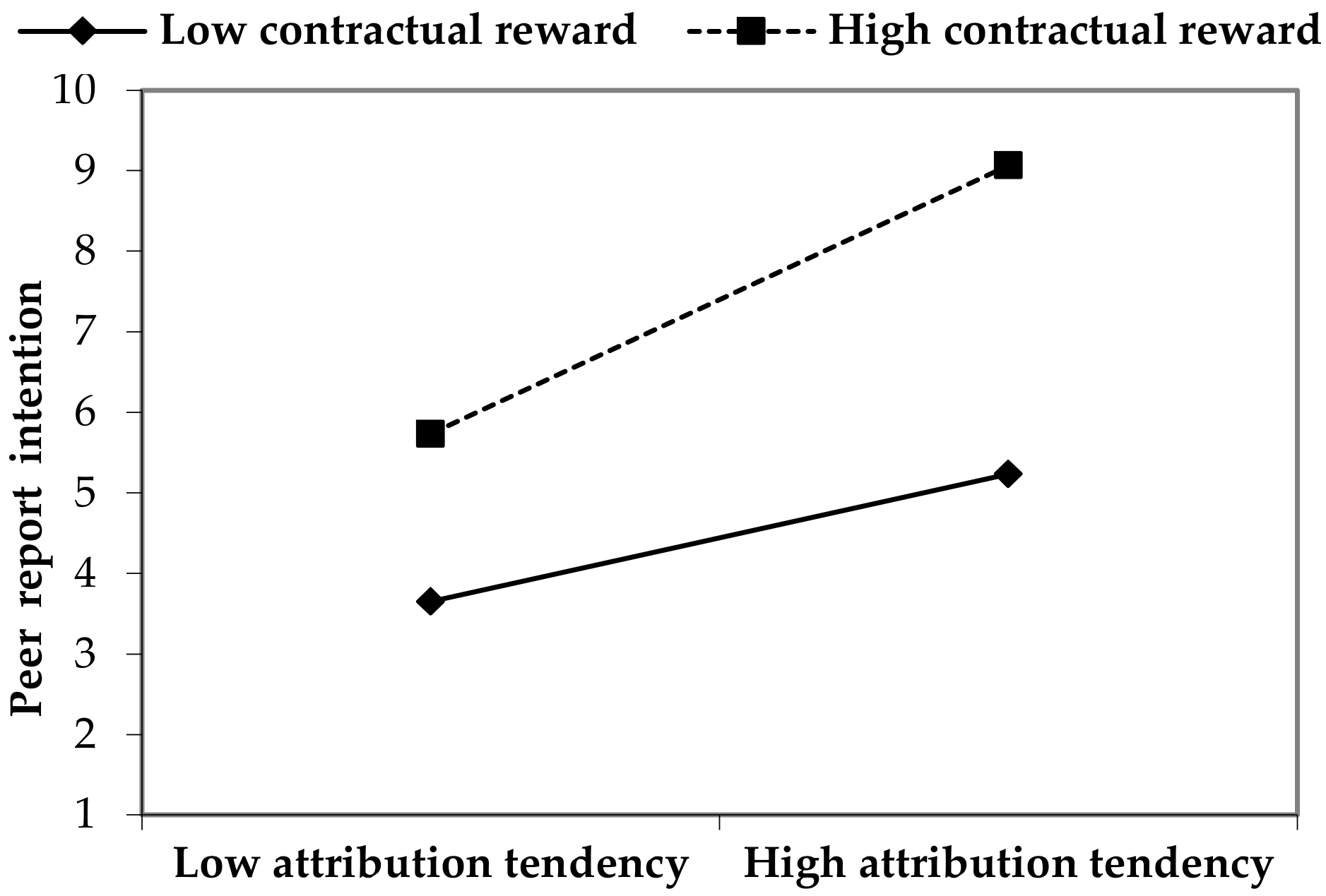

4.2. Hypothesis Testing

4.3. Robustness Checks

5. Discussion

5.1. Hospital Climate and Peer Report Intention

5.2. Attribution Tendency

5.3. Contractual Reward

5.4. Limitation

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Construct/Measurement Item | Reference |

|---|---|

| Peer-reporting intention | Refer to the measurement of Trevino and Victor [1] and Jacobs [24] to measure report willingness directly |

| I will report AMEs that happened in the hospital if I know. | |

| AMEC | Refer to the nine-item and seven-point scale of Dedobbeleer and BeLand [46] and modified in detail according to the study of Curran et al. [47]. |

| (1) how much your supervisors seem to care about AMEs? | |

| (2) how much management commitment to AMEs in your hospital? | |

| (3) how important preventing AMEs to hospital management? | |

| (4) do you regard AMEs responding as an integrated part of the job? | |

| (5) whether do you perceive you would be involved in an AME in the next 12 months? | |

| (6) do you feel pleasant communicating with your supervisor about AMEs? | |

| (7) does your boss take the suggestions about reducing the incidence of AMEs? | |

| (8) do you think the hospital treats you and your colleagues fairly? | |

| (9) do you have that “we are family” feeling with your colleagues? | |

| Attribution Tendency | Refer to the judgments and suppositions of AMEs’ cause, and modified the scale according to Hofmann and Stetzer’s [13] study |

| (1) AMEs are usually caused by health professionals’ carelessness and malpractice (reverse-coded) | |

| (2) it’s hard for health professionals to influence and control whether AMEs exist or not | |

| (3) AMEs are usually caused by time pressure to get the job finished more quickly (reverse-coded) | |

| (4) AMEs are usually caused by poor choices on the part of the health professional(reverse-coded) | |

| (5) AMEs are usually caused by the situation in general (reverse-coded) | |

| (6) AMEs are usually caused by the skill of the health professional in general (reverse-coded) | |

| Contract Reward | Transferred from concept connotation |

| informants will get a cash reward for peer-report on AMEs. | |

| Out-contract Reward | |

| peer-report on AMEs will bring informants favorable impression of supervisors and can help for promotion in future. |

References

- Trevino, L.K.; Victor, B. Peer reporting of unethical behavior: A social context perspective. Acad. Manag. J. 1992, 35, 38–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhassan, R.K.; Halilu, B.; Benin, S.M.; Donyor, B.F.; Kuwaru, A.Y.; Yipaalanaa, D.; Nketiah-Amponsah, E.; Ayanore, M.A.; Abuosi, A.A.; Afaya, A.; et al. Experiences of frontline nurses with adverse medical events in a regional referral hospital in Northern Ghana: A cross-sectional study. Trop. Med. Health 2019, 47, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, D.; Yang, X.; Li, X.; Jain, H.K.; Liang, C. Understanding the Role of Mobile Internet-Based Health Services on Patient Satisfaction and Word-of-Mouth. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Patient Safety. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/facts-in-pictures/detail/patient-safety (accessed on 9 March 2019).

- Kable, A.; Kelly, B.; Adams, J. Effects of adverse events in health care on acute care nurses in an Australian context: A qualitative study. Nurs. Health Sci. 2018, 20, 238–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cullen, S.W.; Xie, M.; Vermeulen, J.M.; Marcus, S.C. Comparing Rates of Adverse Events and Medical Errors on Inpatient Psychiatric Units at Veterans Health Administration and Community-based General Hospitals. Med. Care 2019, 57, 913–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIntosh, T.; Higgs, C.; Turner, M.; Partlow, P.; Steele, L.; MacDougall, A.E.; Connelly, S.; Mumford, M.D. To Whistleblow or Not to Whistleblow: Affective and Cognitive Differences in Reporting Peers and Advisors. Sci. Eng. Ethic 2017, 25, 171–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowling, N.A.; Lyons, B.D.; Burns, G.N. Staying Quiet or Speaking Out: Does Peer Reporting Depend on the Type of Counterproductive Work Behavior Witnessed? J. Pers. Psychol. 2020, 19, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AbuAlRub, R.F.; Al-Akour, N.A.; Alatari, N.H. Perceptions of reporting practices and barriers to reporting incidents among registered nurses and physicians in accredited and nonaccredited Jordanian hospitals. J. Clin. Nurs. 2015, 24, 2973–2982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Culiberg, B.; Mihelič, K.K. The impact of mindfulness and perceived importance of peer reporting on students’ response to peers’ academic dishonesty. Ethic. Behav. 2019, 30, 385–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, D.; Deng, S.; Zheng, Q.; Liang, C.; Wu, J. Impacts of case-based health knowledge system in hospital management: The mediating role of group effectiveness. Inf. Manag. 2019, 56, 103162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neal, A.; Griffin, M.; Hart, P. The impact of organizational climate on safety climate and individual behavior. Saf. Sci. 2000, 34, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, D.A.; Stetzer, A. The Role of Safety Climate and Communication in Accident Interpretation: Implications for Learning from Negative Events. Acad. Manag. J. 1998, 41, 644–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiske, S.T.; Taylor, S.E. Social Cognition; Mcgraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Heider, F. The Psychology of Interpersonal Relations; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1958. [Google Scholar]

- Nayır, D.Z.; Rehg, M.T.; Asa, Y. Influence of Ethical Position on Whistleblowing Behaviour: Do Preferred Channels in Private and Public Sectors Differ? J. Bus. Ethic 2016, 149, 147–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, M.K. Predicting Unethical Behavior: A Comparison of the Theory of Reasoned Action and the Theory of Planned Behavior. J. Bus. Ethic 1998, 17, 1825–1834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, B. The climate for service: An application of the climate construct. In Organisational Climate & Culture; Schneider, B., Ed.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1990; pp. 383–412. [Google Scholar]

- Lyu, S.; Hon, C.K.H.; Chan, A.P.C.; Wong, F.K.W.; Javed, A.A. Relationships among Safety Climate, Safety Behavior, and Safety Outcomes for Ethnic Minority Construction Workers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaias, L.M.; Johnson, S.L.; White, R.M.B.; Pettigrew, J.; Dumka, L. Positive School Climate as a Moderator of Violence Exposure for Colombian Adolescents. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2019, 63, 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahl, Ø.; Kongsvik, T. Safety climate and mindful safety practices in the oil and gas industry. J. Saf. Res. 2018, 64, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, L.A.; Huang, Y.-H.; Robertson, M.M.; Jeffries, S.; Dainoff, M.J. A sociotechnical systems approach to enhance safety climate in the trucking industry: Results of an in-depth investigation. Appl. Ergon. 2018, 66, 70–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogus, T.J.; Ramanujam, R.; Novikov, Z.; Venkataramani, V.; Tangirala, S. Adverse Events and Burnout. Med. Care 2020, 58, 594–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, S.; Hann, M.; Bradley, F.; Elvey, R.; Fegan, T.; Halsall, D.; Hassell, K.; Wagner, A.; Schafheutle, E.I. Organisational factors associated with safety climate, patient satisfaction and self-reported medicines adherence in community pharmacies. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2020, 16, 895–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, G.; Pittroff, E.; Turner, M.J. Is a Uniform Approach to Whistle-Blowing Regulation Effective? Evidence from the United States and Germany. J. Bus. Ethic 2018, 163, 553–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirsadeghi, S. A Review on the Attribution Theory in the Social Psychology. IOSR J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2013, 8, 74–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, J.M.; Kirley, E.M.; Rosen, M.A.; Winters, B.D. A comparison of two structured taxonomic strategies in capturing adverse events in U.S. hospitals. Health Serv. Res. 2019, 54, 613–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Suo, T.; Shen, Y.; Geng, C.; Song, Z.; Liu, F.; Wang, J.; Xie, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Tang, T.; et al. Clinicians versus patients subjective adverse events assessment: Based on patient-reported outcomes version of the common terminology criteria for adverse events (PRO-CTCAE). Qual. Life Res. 2020, 29, 3009–3015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen, J. The role of error in organizing behaviour. Ergonics 1990, 33, 1185–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelley, H. Attribution Theory in Social Psychology. In Nebraska Symposium on Motivation; University of Nebraska Press: Lincoln, NE, USA, 1967; Volume 15, pp. 192–238. [Google Scholar]

- Gardner, W.L.; Karam, E.P.; Tribble, L.L.; Cogliser, C.C. The missing link? Implications of internal, external, and relational attribution combinations for leader–member exchange, relationship work, self-work, and conflict. J. Organ. Behav. 2019, 40, 554–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Victor, B.; Trevino, L.K.; Shapiro, D.L. Peer reporting of unethical behavior: The influence of justice evaluations and social context factors. J. Bus. Ethic 1993, 12, 253–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heggeness, L.F.; Lechner, W.V.; Ciesla, J.A. Coping via substance use, internal attribution bias, and their depressive interplay: Findings from a three-week daily diary study using a clinical sample. Addict. Behav. 2019, 89, 70–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, Y.; Yang, J.; Zhang, J.; Luo, M.; Zhang, Z.; Liang, H. Motivating Physicians to Report Adverse Medical Events in China: Stick or Carrot? J. Patient Saf. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Near, J.P.; Miceli, M.P. Effective-Whistle Blowing. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 679–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Englmaier, F.; Muehlheusser, G.; Roider, A. Optimal Incentive Contracts under Moral Hazard When the Agent is Free to Leave. SSRN Electron. J. 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Niu, Y.; Yang, J.; Zou, Z. Robust contracts with one-sided commitment. J. Econ. Dyn. Control. 2020, 117, 103942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Belief, Attitude, Intention and Behaviour: An Introduction to Theory and Research; Addison-Wesley: Reading, MA, USA, 1975; Volume 27. [Google Scholar]

- Knockaert, M.; Der Foo, M.; Erikson, T.; Cools, E. Growth intentions among research scientists: A cognitive style perspective. Technovation 2015, 38, 64–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, R.K. Ethical judgement, locus of control, and whistleblowing intention: A case study of mainland Chinese MBA students. Manag. Audit. J. 2002, 17, 581–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Haultfœuille, X.; Février, P. The provision of wage incentives: A structural estimation using contracts variation. Quant. Econ. 2020, 11, 349–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, D.-X.; Liang, C.; Zhao, H. A case-based reasoning system based on weighted heterogeneous value distance metric for breast cancer diagnosis. Artif. Intell. Med. 2017, 77, 31–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flynn, G.; Hogan, J.; Feeney, S. Whistleblowing in the Irish Military: The Cost of Exposing Bullying and Sexual Harassment. J. Mil. Ethic 2019, 18, 129–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.Q.; Zhang, X.Z.; Nie, C. Cause analysis of nurse negative event. Forum Hosp. Manag. 2008, 25, 39–41. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, J.-Y.; Wu, Y.-W.B. Nurses’ intention to report child abuse in Taiwan: A test of the theory of planned behavior. Res. Nurs. Health 2005, 28, 337–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dedobbeleer, N.; Béland, F. WITHDRAWN: Reprint of “A safety climate measure for construction sites”. J. Saf. Res. 2013, 22, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curran, C.; Lydon, S.; Kelly, M.; Murphy, A.; Walsh, C.; O’Connor, P. A Systematic Review of Primary Care Safety Climate Survey Instruments: Their Origins, Psychometric Properties, Quality, and Usage. J. Patient Saf. 2018, 14, e9–e18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J.C. Psychometric Theory 3E; Tata McGraw-Hill Education: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Söderberg, J.; Grankvist, K.; Brulin, C.; Wallin, O. Incident reporting practices in the preanalytical phase: Low reported frequencies in the primary health care setting. Scand. J. Clin. Lab. Investig. 2009, 69, 731–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liukka, M.; Hupli, M.; Turunen, H. How transformational leadership appears in action with adverse events? A study for Finnish nurse manager. J. Nurs. Manag. 2017, 26, 639–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Li, G. To gain or not to lose? The effect of monetary reward on motivation and knowledge contribution. J. Knowl. Manag. 2017, 21, 397–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrøder, K.; Lamont, R.F.; Jørgensen, J.S.; Hvidt, N.C. Second victims need emotional support after adverse events: Even in a just safety culture. BJOG Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2019, 126, 440–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seys, D.; Wu, A.W.; Van Gerven, E.; Vleugels, A.; Euwema, M.; Panella, M.; Scott, S.D.; Conway, J.; Sermeus, W.; Vanhaecht, K. Health Care Professionals as Second Victims after Adverse Events. Eval. Health Prof. 2012, 36, 135–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greitemeyer, T.; Weiner, B. The asymmetrical consequences of reward and punishment on attributional judgments. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2003, 29, 1371–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eisenmann, D.; Stroben, F.; Gerken, J.D.; Exadaktylos, A.K.; Marchner, M.; Hautz, W.E. Interprofessional Emergency Training Leads to Changes in the Workplace. West. J. Emerg. Med. 2018, 19, 185–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Health Professionals | Number (N = 503) | Proportion | Health Professionals | Number (N = 503) | Proportion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Years of working | ||||

| Man | 304 | 60.4% | Under 4 | 119 | 23.7% |

| woman | 199 | 39.6% | 5–9 | 153 | 30.4% |

| Age | 10–19 | 121 | 24.1% | ||

| Under 30 | 121 | 24.0% | 20–40 | 110 | 21.8% |

| 30–34 | 146 | 29.0% | Professional title | ||

| 35–39 | 125 | 24.9% | No title | 148 | 29.4% |

| Over 40 | 111 | 22.1% | Junior | 161 | 32.0% |

| Education | Middle | 132 | 26.3% | ||

| Below junior college | 36 | 7.1% | Senior | 62 | 12.3% |

| Junior college | 134 | 26.6% | |||

| Undergraduate | 197 | 39.2% | |||

| Master and above | 136 | 27.1% |

| Variable | Mean | S.D. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Peer report intention | 3.4592 | 1.67767 | 1 | |||||||||

| 2 Education | 2.7117 | 0.73772 | −0.009 | 1 | ||||||||

| 3 Seniority | 5.8827 | 5.69687 | 0.186 ** | 0.001 | 1 | |||||||

| 4 Ownership | 1.3360 | 0.47280 | −0.072 | −0.042 | 0.069 | 1 | ||||||

| 5 Scale | 2.8211 | 0.54644 | −0.023 | 0.139 ** | 0.080 | 0.025 | 1 | |||||

| 6 Work Stability | 3.3917 | 1.69828 | 0.295 ** | −0.019 | −0.124 ** | 0.037 | −0.070 | 1 | ||||

| 7 Contractual Reward | 3.0676 | 1.48143 | 0.191 ** | 0.054 | −0.033 | −0.021 | −0.128 ** | 0.027 | 1 | |||

| 8 Extra-contractual Reward | 3.0378 | 1.54757 | 0.171 ** | 0.126 ** | 0.018 | −0.036 | −0.192 ** | 0.072 | 0.638 ** | 1 | ||

| 9 AMEC | 3.5968 | 1.23090 | 0.327 ** | 0.003 | 0.137 ** | −0.074 | 0.073 | 0.083 | 0.152 ** | 0.121 ** | 1 | |

| 10 Attribution tendency | 3.8210 | 1.27149 | −0.329 ** | −0.063 | −0.206 ** | 0.099 * | 0.063 | 0.027 | −0.012 | −0.064 | −0.312 ** | 1 |

| Variable | Peer Report Intention | Attribution Tendency | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | Model 7 | |

| Intercept | 1.736 *** (0.520) | 0.904 † (0.520) | 3.123 *** (0.527) | 2.298 *** (0.554) | 1.892 * (0.697) | 3.533 *** (0.421) | 4.373 *** (0.436) |

| Education | −0.052 (0.095) | −0.038 (0.091) | −0.096 (0.090) | −0.078 (0.089) | −0.059 (0.087) | −0.111 (0.077) | −0.128 † (0.074) |

| Seniority | 0.069 *** (0.012) | 0.058 *** (0.012) | 0.050 *** (0.012) | 0.046 *** (0.012) | 0.049 *** (0.011) | −0.049 *** (0.010) | −0.044 *** (0.010) |

| Ownership | −0.341 * (0.145) | −0.265 † (0.140) | −0.227 (0.138) | −0.193 (0.136) | −0.212 (0.140) | 0.291 * (0.117) | 0.223 * (0.112) |

| Scale | 0.046 (0.130) | −0.030 (0.126) | 0.120 (0.123) | 0.054 (0.122) | 0.043 (0.123) | 0.187 † (0.105) | 0.257 * (0.101) |

| Work Stability | 0.317 *** (0.041) | 0.291 *** (0.039) | 0.318 *** (0.039) | 0.300 *** (0.038) | 0.310 *** (0.039) | 0.003 (0.033) | 0.019 (0.030) |

| Contractual Reward | 0.187 ** (0.060) | 0.148 * (0.058) | 0.197 *** (0.057) | 0.167 ** (0.056) | 0.109 ** (0.037) | 0.025 (0.048) | 0.054 (0.049) |

| Extra-contractual Reward | 0.045 (0.059) | 0.034 (0.057) | 0.028 (0.056) | 0.023 (0.055) | 0.065 (0.098) | −0.042 (0.048) | −0.035 (0.049) |

| AMEC | 0.335 *** (0.055) | 0.166 * (0.076) | 0.252 *** (0.053) | 0.431 *** (0.052) | |||

| Attribution tendency | 0.325 *** (0.054) | 0.393 *** (0.053) | 0.193 (0.121) | ||||

| Attribution × contract | 0.233 *** (0.049) | ||||||

| Attribution × extra-contract | −0.077 * (0.032) | ||||||

| R2 | 0.184 | 0.240 | 0.266 | 0.292 | 0.306 | 0.068 | 0.153 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.172 | 0.228 | 0.254 | 0.279 | 0.290 | 0.055 | 0.139 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, X.; Zhang, S.; Chen, R.; Gu, D. Hospital Climate and Peer Report Intention on Adverse Medical Events: Role of Attribution and Rewards. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2725. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18052725

Li X, Zhang S, Chen R, Gu D. Hospital Climate and Peer Report Intention on Adverse Medical Events: Role of Attribution and Rewards. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(5):2725. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18052725

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Xiaoxiang, Shuhan Zhang, Rong Chen, and Dongxiao Gu. 2021. "Hospital Climate and Peer Report Intention on Adverse Medical Events: Role of Attribution and Rewards" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 5: 2725. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18052725

APA StyleLi, X., Zhang, S., Chen, R., & Gu, D. (2021). Hospital Climate and Peer Report Intention on Adverse Medical Events: Role of Attribution and Rewards. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(5), 2725. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18052725