1. Introduction

In 2015, the Sustainable Development Goals set out the ambitious targets of ending the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) epidemic and achieving universal health coverage by 2030 [

1]. This was followed by the goal of eliminating new human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infections in children by 2018 [

2]. Yet, in 2019, 150,000 children under 15 years became infected with HIV. The majority of these infections occurred in Sub-Saharan Africa, and in Tanzania, there were an estimated 6300 cases of new HIV infections in this age group [

3].

The primary cause of HIV infection in children is vertical transmission, accounting for over 90% of infections in children under 15 years [

4]. The risk of mother-to-child transmission of HIV (MTCT) from an untreated mother ranges from 15–45%. Breastfeeding increases the risk of MTCT [

5], but in resource-poor countries this risk is generally counterbalanced by prevention of other severe infections.

In resource-rich settings, prevention of MTCT (PMTCT) interventions including antiretroviral therapy (ART) in pregnancy, use of caesarean section in mothers with HIV viraemia, and avoidance of breastfeeding have reduced the risk of MTCT to less than 2% [

6]. Similar results have also been demonstrated in some studies from Africa [

7,

8,

9]. However, UNAIDS reported a vertical transmission rate of 11% in Tanzania in 2019 [

3].

The PMTCT cascade is a series of key stepwise activities, starting with diagnosis and treatment of all pregnant women, continuing with newborn antiretroviral prophylaxis, and ending with the determination of HIV status of HIV-exposed infants (HEIs) at 18 months of age [

10].

In Tanzania, PMTCT activities include regular HIV-testing during pregnancy and at the time of delivery, and provision of lifelong ART for all HIV-infected women. Antiretroviral (ARV) prophylaxis is recommended for HEIs during the first 6 weeks of life. In addition, cotrimoxazole preventive therapy (CPT) is recommended for newborns from age 4–6 weeks and until HIV infection has been ruled out after complete cessation of breastfeeding. Exclusive breastfeeding is recommended for the first 6 months, followed by mixed feeding until 12 months, before cessation of breastfeeding by month 13. Other measures include family planning and referral of HIV-infected infants to Care and Treatment Clinics (CTCs) [

4].

Although PMTCT activities are in place in most resource-constrained countries, there is a need for studies that examine in depth the level of implementation and quality of documentation at the health facility level, and how this may affect the reported rate of MTCT.

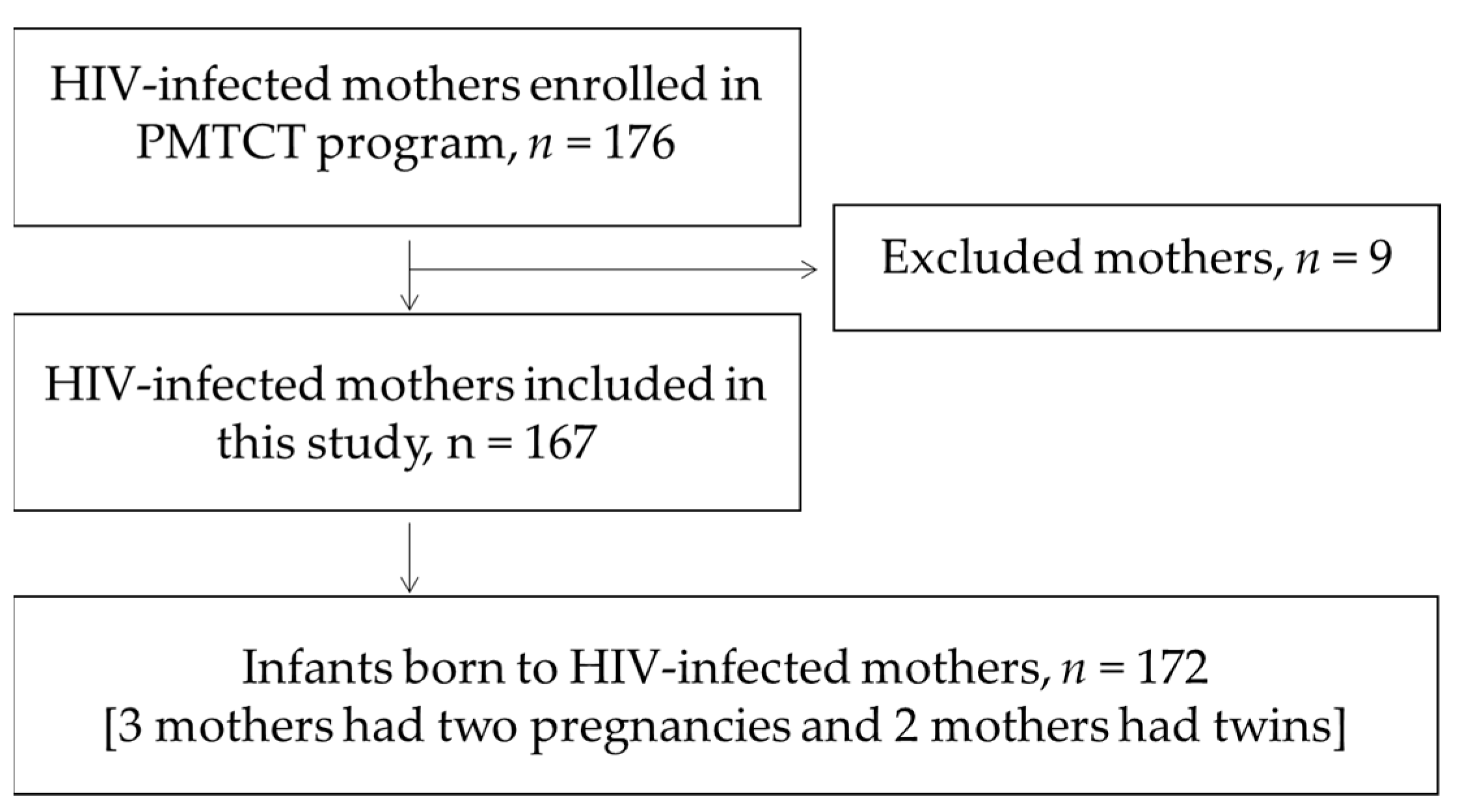

The aims of our study were to assess the occurrence of MTCT by age 18 months, the influence of known predictors on transmission, and the implementation of PMTCT measures as described in the Tanzanian national guidelines.

4. Discussion

MTCT is a major public health challenge in many resource-poor countries. We found that 10.2% of HEIs with known outcome at 18 months were infected. Factors associated with MTCT included mothers not taking ART in pregnancy, maternal CD4 cell count <200 cells/mm3, and late HIV DNA PCR testing of infants (>2 months). However, for almost one half of the children enrolled in the postnatal PMTCT program we were unable to ascertain if the children were infected, largely due to loss to follow-up and transfer out to other health care providers. Several weaknesses in the implementation of the PMTCT program were identified in relation to prevention and diagnosis of HIV infection and follow-up of exposed children.

The rate of MTCT in our study is in close agreement with the Tanzanian national rate of 11% in 2019 [

3], and also with two earlier studies that found transmission rates of 9.6 and 10.5% [

12,

13]. None of the infected children in our study had a second confirmatory HIV PCR test. We therefore cannot exclude the occurrence of false-positive tests. A study from South Africa reported a positive predictive value (PPV) of 94.4% for the first HIV DNA PCR test result after confirmatory re-testing [

14]. We therefore propose that greater emphasis be put on performing a confirmatory test, and that this is documented in the HIV-exposed child follow-up register.

Although we could not determine the HIV status at age 18 months in almost one half of the children, two factors suggest that the rate of transmission in this group is likely to be low. First, the indeterminable group was similar to the uninfected group and differed significantly from the infected group in terms of several known predictors of MTCT, including the mothers’ use of ART, her CD4 cell counts, and WHO stage. Second, studies conducted before the era of ART demonstrated that roughly one third of children were infected in utero, one third during birth, and a further one third by breastfeeding [

15]. However, for women on effective ART the risk of transmission is very low, with a target of less than 5% transmission among breastfeeding women [

5]. In the indeterminable group, 78 children (92.9%) had an early PCR test that was negative, practically excluding in utero and peripartum transmission. These factors suggest that the proportion of infected children in the indeterminable group is likely to be considerably lower than 10.2%. On the other hand, children lost to follow-up may be at increased risk of HIV infection from mothers that have stopped taking ART [

16]. Furthermore, testing may have been performed less than 6 weeks after cessation of breastfeeding in some cases, as we accepted a negative rapid test as indication of absence of MTCT, even in the case of poorly documented number of weeks after stopping breastfeeding. Therefore, undetected MTCT may have occurred later. To ensure correct timing of testing after cessation of breastfeeding, we propose inserting an extra column specifically for “Date of cessation of breastfeeding” or “Number of weeks since cessation of breastfeeding at the time of HIV-testing”. On balance, we find it likely that the rate of transmission in the entire study population is between 10.2 % and 5.2%, most likely in the lower end of this range.

We found that not taking ART during pregnancy was significantly associated with the likelihood of MTCT. There was also a smaller and non-significant increase in risk of MTCT among children who did not receive infant ARV prophylaxis. Our results may indicate that maternal ART is a more important protective factor than infant ARV prophylaxis. This is in agreement with previous studies from Kenya, Zambia and Nigeria [

17,

18,

19].

Early diagnosis, treatment, and retention in care of the women are challenges in our rural setting in Tanzania. Prescription of antiretroviral drugs, both for treatment of the mother and prophylaxis in the child, will only be effective if the mother is compliant with treatment and provision of prophylaxis to her infant. Additionally, HIV resistance may threaten the success of PMTCT activities. Other studies have demonstrated that resistance to non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors such as nevirapine is common in HIV -infected infants in Tanzania [

20,

21]. Therefore, monitoring of resistance to all classes of ARVs is required both on population and individual level in order to prevent MTCT.

Only 27.3% of the children had a first HIV PCR test as recommended at 4–6 weeks of age. This is even lower than the 57.1% reported in another recent study from North-East Tanzania [

22]. Testing after 2 months of age was associated with significantly higher odds of infection, in agreement with previous studies from Tanzania and Ethiopia [

12,

23]. The association between late testing and vertical transmission may be caused by older infants tending to present for diagnostic testing because of symptoms, as opposed to routine early infant screening. The association may also be due to confounding factors like increased risk behavior among mothers of late enrollers at RCHS. We propose that greater effort be placed on encouraging and reminding mothers to bring in their children at the age of 4–6 weeks. Additionally, we propose that HIV DNA PCR testing be introduced on site to prevent delays caused by slow turnaround time.

The odds of MTCT were over 15 times higher among mothers with CD4 cell counts <200 compared to mothers with higher levels. Similarly, a study from South Africa found that higher maternal baseline CD4 cell count was associated with reduced odds of MTCT [

8]. Low CD4 cell counts may be a result of late initiation of treatment, antiviral resistance, or poor adherence to therapy caused by stigma, logistic challenges, or lack of understanding. Low CD4 cell counts probably reflect no or ineffective ART—resulting in high viral load and subsequent high risk of MTCT.

The WHO recommends CPT after week 4–6 to prevent bacterial infections, malaria and

Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia [

24]. We found that the majority of HEIs started CPT at a later age, possibly putting the children at risk of severe infections. However, the recommendation to give CPT to HIV-exposed, HIV-uninfected infants is based on very-low-quality evidence [

24]. A recent study from South Africa suggests that co-trimoxazole prophylaxis provides no benefit after age 6 weeks for HIV-uninfected breastfed infants in countries that are unaffected by malaria [

25]. Malaria is not highly prevalent in children seen at our hospital, and it is possible that that failure to provide CPT in HIV-uninfected infants may not be of great concern.

Only five of nine HIV-infected children (55.6%) in our study were referred to the CTC, and a previous study from Tanzania found that a mere one third of children with an early positive PCR test had documented referral to therapy [

20]. The clinical course of HIV infection is often aggressive in children not offered ART. By one year, an estimated one third of children will have died, and by two years approximately one half [

26,

27]. Increased likelihood of malnourishment and illness among loss to follow-up infants compared to children retained in care [

28], further contribute to the risk of death. Food supplementation has been found to be protective against loss to follow-up among HIV- exposed infants by acting as an incentive for continued pediatric care and treatment [

29]. Food supplementation may also help reduce malnourishment, which is associated not only with loss to follow-up, but also with increased mortality. The WHO recommends integrating HIV prevention, care and treatment services with reproductive and child health services to reduce overall maternal and child mortality [

30]. Stronger linkage between services would help identifying mothers and children at risk of loss to follow-up, and thereby improve retention in care.

Of all children enrolled in our study, one third (32.0%) was lost to follow-up for unknown reasons, and one-eighth (12.7%) was transferred out to other health care providers. This largely explains why we were unable to adequately determine the HIV status at age 18 months in almost one half of the exposed children. Long distances, cost of travel and poor communications in our rural area may be good reasons for transfer of patients to health care providers nearer to the home. Loss to follow-up for unknown reasons is a greater cause for concern and has also been identified as a significant challenge in several other studies from Africa [

13,

17,

19,

28,

31]. In addition to the above factors, stigma associated with HIV is a likely explanation for the high rate of loss to follow-up.

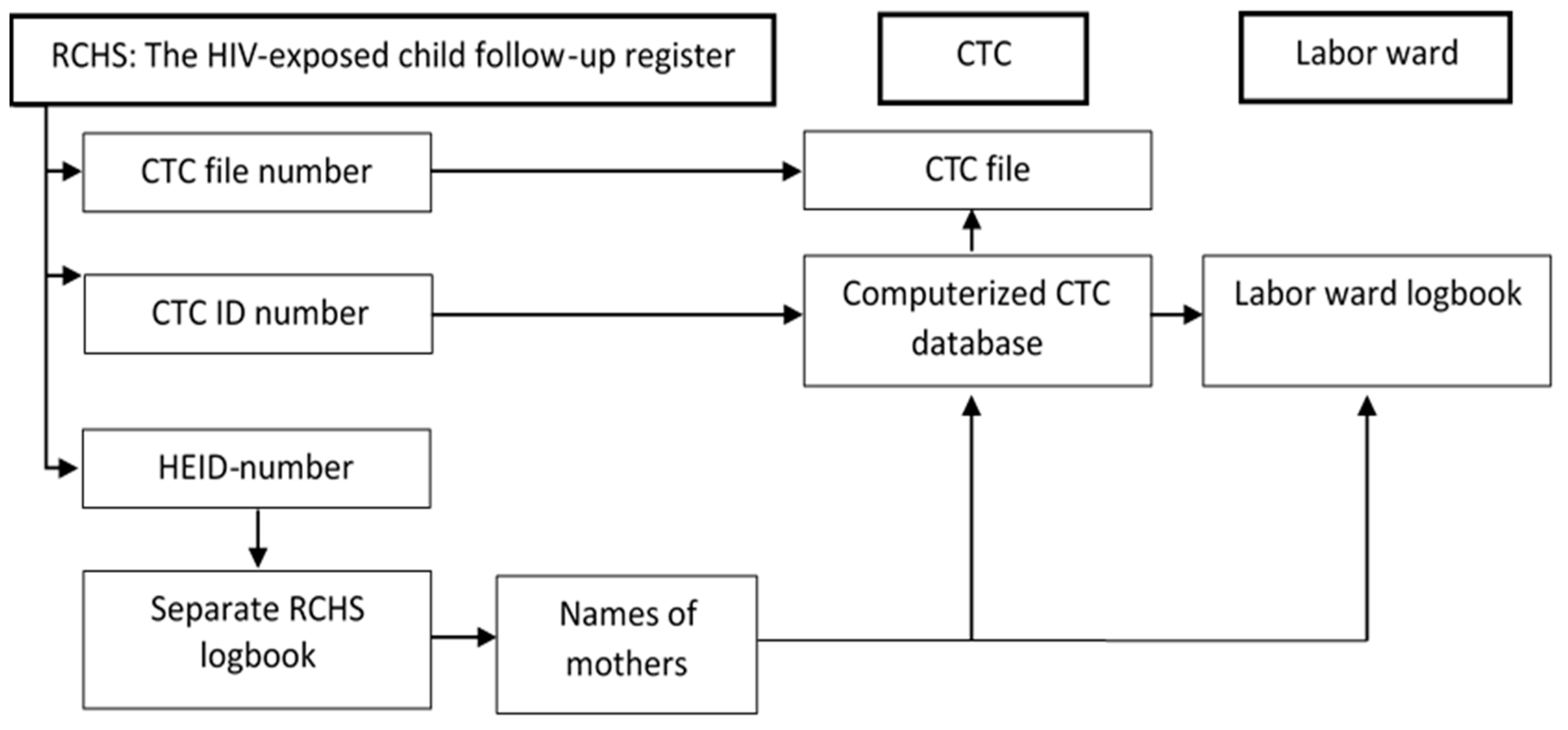

Linkage of data and continuity of care between different health service providers within and outside the hospital is challenging. In our hospital, HIV-infected mothers and their children receive HIV-related services from RCHS, Labor Ward, and CTC. These are located in separate buildings and are staffed by separate groups of health care workers who enter data into different medical registers and records. The large amount of paperwork and frequent updates in reporting systems constitute a heavy workload for the staff that may result in failure to correctly and comprehensively document all required aspects of PMTCT. Our observations are in accordance with other studies from South Africa and Tanzania which have found that a multiplicity of registers contributes to unnecessary complexity and inaccuracy of data [

32,

33]. Lack of coordination and poor data quality may impede effective follow-up, treatment, and retention in care.

There is therefore a need for ongoing training of health care personnel in correct and complete documentation. In addition, we propose that regular auditing of logbooks and patient files be implemented. To strengthen the linkage between medical records at RCHS and CTC, we suggest that the mother’s CTC ID numbers be accurately recorded in all PMTCT registers and records, and that HEI numbers, test results, and infant prophylaxis be recorded in the mother’s CTC file. Reducing the number of PMTCT registers and records using a minimal common set of key indicators, as well as closer proximity of service locations, may facilitate follow-up and reduce paperwork for health workers [

33,

34]. Unfortunately, required care and treatment for HIV is still associated with stigma, and this continues to be an impediment to closer integration of CTC activities in the ordinary services of the hospitals in Africa.

The principal strength of this study is the “real world” rural setting and having collected information from a wide range of clinical records and registries that are routinely available in a hospital. By this approach, we have been able to identify and describe practical challenges in the postnatal PMTCT program in Tanzania. In contrast, most PMTCT studies are performed in well-resourced centers or are based on programmatic data. However, our study also has clear limitations, mainly related to the large group of children with incomplete data and indeterminable HIV status at 18 months. However, in the context of public health, this is an important finding that merits attention by health officials in order to improve care for HEIs. Another limitation is the relatively small study population in a single institution. The external validity of our study is therefore uncertain, but we have no reason to believe that the challenges identified in our hospital are of less concern in other rural hospitals. Finally, we did not have information on HIV viral load or resistance in sufficient individuals to include these parameters in our study.