Mobile-Health Technologies for a Child Neuropsychiatry Service: Development and Usability of the Assioma Digital Platform

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Stage 1. Development

- (A)

- Support data collection and organization and to provide effective information;

- (B)

- Promote constant and remote communication between patients, caregivers and clinicians;

- (C)

- Promote families’ active involvement in the DH processing, during and after the DH visits.

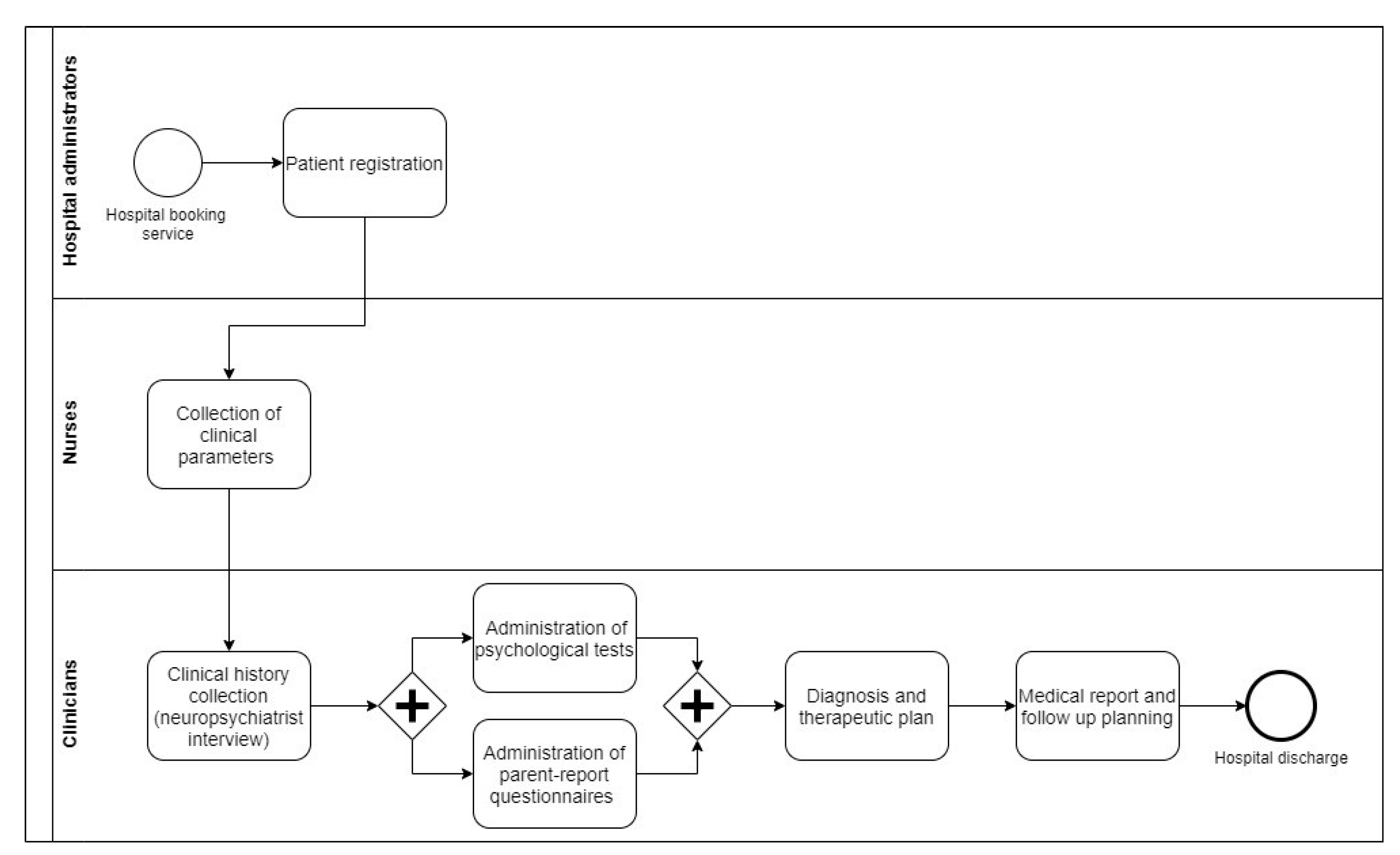

2.1.1. Analysis of the Functional Requirements

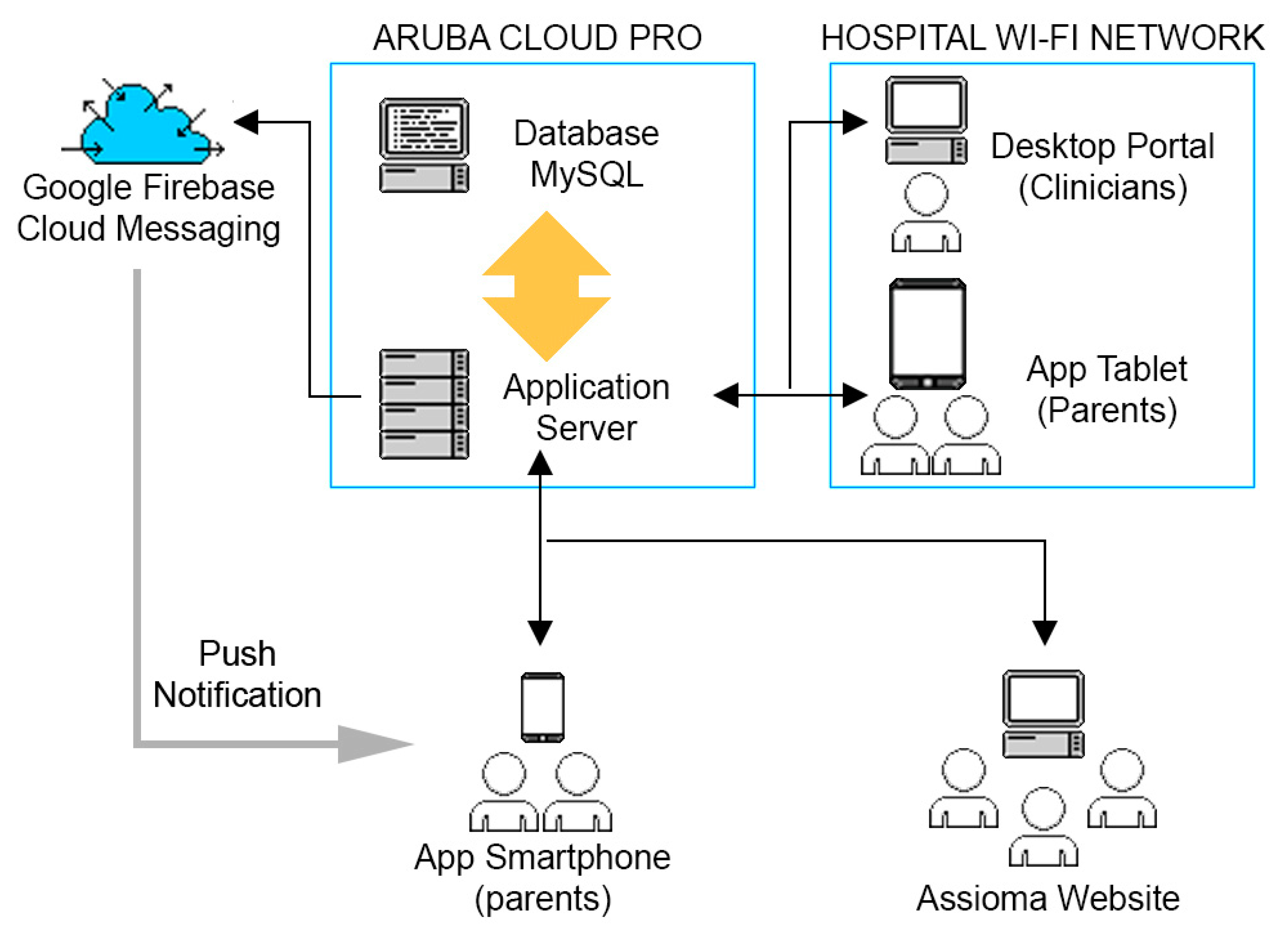

2.1.2. Design of the Assioma’s Architecture

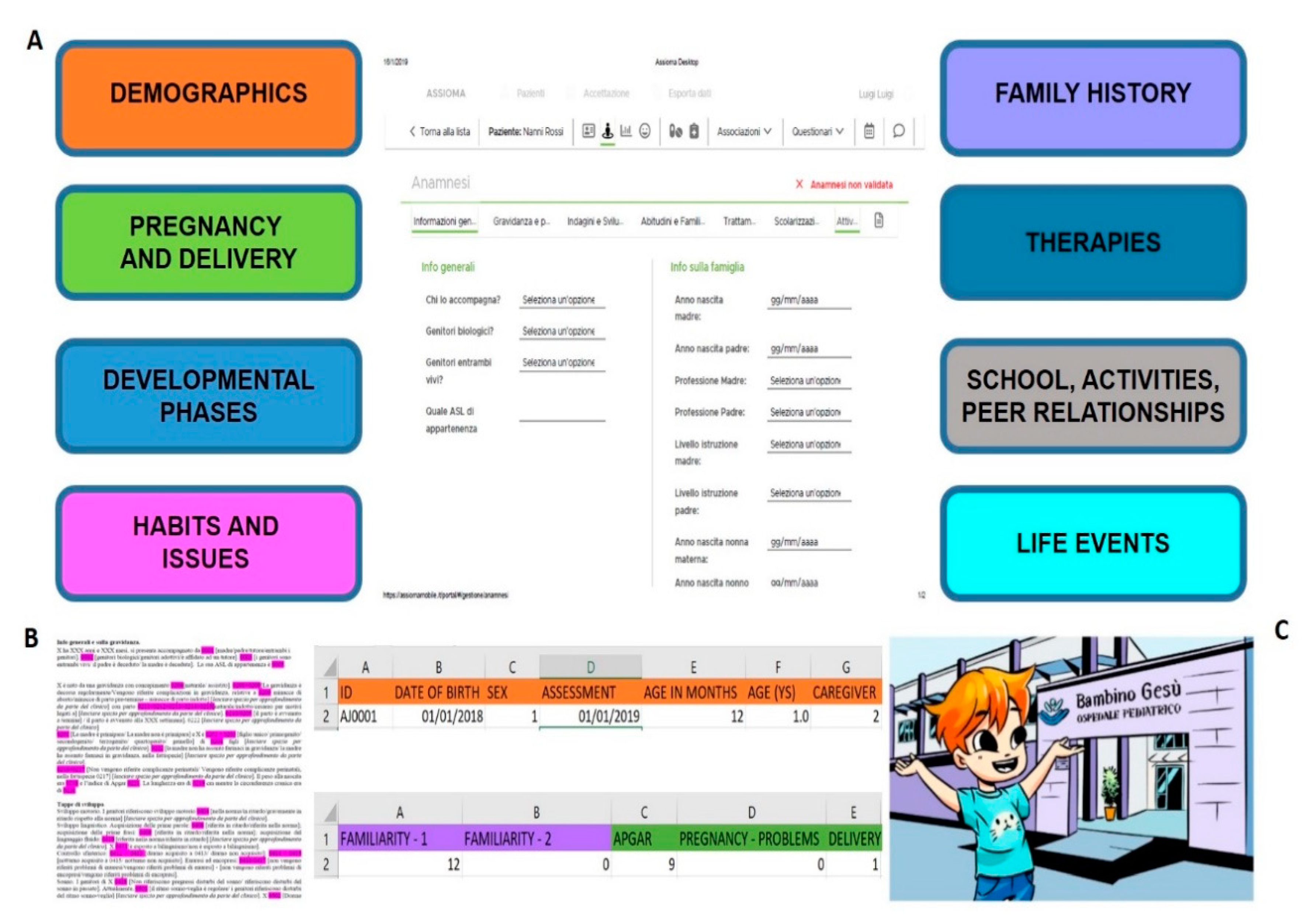

2.1.3. Definition of Functionalities and Contents

- 1)

- Assioma Desktop was developed for PC, dedicated to clinicians. It contained the information sheet and videos associated with families’ accounts, patient registration and data entry of patients’ physiological parameters functions, possible drugs prescription, medication intake monitoring, DH appointment management and notifications. Through such functionality, clinicians could consult information provided by caregivers filling in the clinical history questionnaire, and then validating it during the interview. Once anamnestic information included in the questionnaire was validated by the clinician, it was automatically exported in text and Excel standard formats. Editable text format was designed accordingly to the format used for hospital discharge, thus only a selected amount of information was included in the editable text form. All the information collected by the anamnestic questionnaire were thus coded and automatically organized in a database format.

- 2)

- Assioma Parents was developed for tablet for families during clinical activities. It contained summary information on neurodevelopmental and neuropsychiatric pathologies (epidemiology, etiology, age of onset) to be associated with a participant account at check-in in case of a second visit (according to previous diagnosis) or, in the case of a first visit, at the moment of hospital discharge (according to the diagnosis at the moment of discharge).

- 3)

- Assioma Diary was developed for smartphones, to allow families to use the application outside of the hospital. It contained two of the same functionalities as Assioma Parents (video cartoons and informative sheets), and a push notification service to receive direct communication from clinicians about the ongoing DH procedures (e.g., “appointment at 10.30 in room three after the break”), plus the agenda of future appointments.

2.2. Stage 2. Pilot Test

2.2.1. Families and Clinicians’ Enrollment

2.2.2. Procedure

2.2.3. Questionnaires and Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Usability Questionnaire

3.2. Satisfaction Questionnaire

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Silva, B.M.; Rodrigues, J.J.; Díez, I.D.L.T.; López-Coronado, M.; Saleem, K. Mobile-health: A review of current state in 2015. J. Biomed. Inform. 2015, 56, 265–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Vargas, B.R.; Ferrández, J.S.-R.; Fuentes, J.G.; Velayos, R.; Verdugo, R.M.; Piñol, F.S.; González, A.O.; Sagrado, M.; Ángel, R. Usability and Acceptability of a Comprehensive HIV and Other Sexually Transmitted Infections Prevention App. J. Med. Syst. 2019, 43, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrett, M.A.; Humblet, O.; Marcus, J.E.; Henderson, K.; Smith, T.; Eid, N.; Sublett, J.W.; Renda, A.; Nesbitt, L.; Van Sickle, D.; et al. Effect of a mobile health, sensor-driven asthma management platform on asthma control. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2017, 119, 415–421.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, J.; Ebert, L.; Xue, Z.; Shen, Q.; Chan, S.W.-C. Development of a mobile application of Breast Cancer e-Support program for women with breast cancer undergoing chemotherapy. Technol. Health Care 2017, 25, 377–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.-H.; Chung, Y.-F.; Chen, T.-S.; Wang, S.-D. Mobile Agent Application and Integration in Electronic Anamnesis System. J. Med. Syst. 2010, 36, 1009–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, G.; Khajuria, A.; Arora, S.; King, D.; Ashrafian, H.; Darzi, A. The impact of mobile technology on teamwork and communication in hospitals: A systematic review. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2019, 26, 339–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torous, J.; Friedman, R.; Keshavan, M. Smartphone Ownership and Interest in Mobile Applications to Monitor Symptoms of Mental Health Conditions. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2014, 2, e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grist, R.; Porter, J.; Stallard, P. Mental Health Mobile Apps for Preadolescents and Adolescents: A Systematic Review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2017, 19, e176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Turvey, C.; Fortney, J. The Use of Telemedicine and Mobile Technology to Promote Population Health and Population Management for Psychiatric Disorders. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2017, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, M.E.; Nicholas, J.; Christensen, H. A Systematic Assessment of Smartphone Tools for Suicide Prevention. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0152285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittaker, R.; Stasiak, K.; McDowell, H.; Doherty, I.; Shepherd, M.; Chua, S.; Dorey, E.; Parag, V.; Ameratunga, S.; Rodgers, A.; et al. MEMO: An mHealth intervention to prevent the onset of depression in adolescents: A double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2017, 58, 1014–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kauer, S.D.; Reid, S.C.; Crooke, A.H.D.; Khor, A.; Hearps, S.J.C.; Jorm, A.F.; Sanci, L.; Patton, G. Self-monitoring Using Mobile Phones in the Early Stages of Adolescent Depression: Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Med. Internet Res. 2012, 14, e67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubad, M.; Winsper, C.; Meyer, C.; Livanou, M.; Marwaha, S. A systematic review of the psychometric properties, usability and clinical impacts of mobile mood-monitoring applications in young people. Psychol. Med. 2018, 48, 208–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Pennant, M.E.; Loucas, C.E.; Whittington, C.; Creswell, C.; Fonagy, P.; Fuggle, P.; Kelvin, R.; Naqvi, S.; Stockton, S.; Kendall, T. Computerised therapies for anxiety and depression in children and young people: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Behav. Res. Ther. 2015, 67, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vigerland, S.; Lenhard, F.; Bonnert, M.; Lalouni, M.; Hedman, E.; Ahlen, J.; Olén, O.; Serlachius, E.; Ljótsson, B. Internet-delivered cognitive behavior therapy for children and adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2016, 50, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilansky, P.; Eklund, J.M.; Milner, T.; Kreindler, D.; Cheung, A.; Kovacs, T.; Shooshtari, S.; Astell, A.; Ohinmaa, A.; Henderson, J.; et al. Cognitive Behavior Therapy for Anxious and Depressed Youth: Improving Homework Adherence Through Mobile Technology. JMIR Res. Protoc. 2016, 5, e209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Weisman, O.; Schonherz, Y.; Harel, T.; Efron, M.; Elazar, M.; Gothelf, D. Testing the Efficacy of a Smartphone Application in Improving Medication Adherence, Among Children with ADHD. Isr. J. Psychiatry Relat. Sci. 2018, 55, 59–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costantino, A. Rete dei Servizi per i Disturbi Neuropsichici dell’età Evolutiva: Risorse e Criticità; Rapporti ISTISAN 17/16; 2017. Available online: https://www.iss.it/documents/20126/45616/17_16_web.pdf/180e0642-b28c-cc3d-db59-a3204227b896?t=1581099285972#page=16 (accessed on 17 May 2018).

- Eden, R.; Burton-Jones, A.; Scott, I.; Staib, A.; Sullivan, C. Effects of eHealth on hospital practice: Synthesis of the current literature. Aust. Health Rev. 2018, 42, 568–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Melby, L.; Hellesø, R. Introducing electronic messaging in Norwegian healthcare: Unintended consequences for interprofessional collaboration. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2014, 83, 343–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saddik, B.; Al-Mansour, S. Does CPOE support nurse-physician communication in the medication order process? A nursing perspective. Stud. Health Technol. Inform. 2014, 204, 149–155. [Google Scholar]

- Keasberry, J.; Scott, I.A.; Sullivan, C.; Staib, A.; Ashby, R. Going digital: A narrative overview of the clinical and organisational impacts of eHealth technologies in hospital practice. Aust. Health Rev. 2017, 41, 646–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liszio, S.; Masuch, M. Virtual Reality MRI: Playful Reduction of Children’s Anxiety in MRI Exams. In Proceedings of the 2017 Conference on Interaction Design and Children IDC′17, Stanford, CA, USA, 27–30 June 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buffel, C.; Van Aalst, J.; Bangels, A.-M.; Toelen, J.; Allegaert, K.; Verschueren, S.; Stichele, G.V.; Antoniades, A.; Bestek, M. A Web-Based Serious Game for Health to Reduce Perioperative Anxiety and Pain in Children (CliniPup): Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial. JMIR Serious Games 2019, 7, e12431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kim, J.; Chiesa, N.; Raazi, M.; Wright, K.D. A systematic review of technology-based preoperative preparation interventions for child and parent anxiety. Can. J. Anesth. 2019, 66, 966–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bray, L.; Sharpe, A.; Gichuru, P.; Fortune, P.-M.; Blake, L.; Appleton, V. The Acceptability and Impact of the Xploro Digital Therapeutic Platform to Inform and Prepare Children for Planned Procedures in a Hospital: Before and After Evaluation Study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e17367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tozzi, A.E.; Carloni, E.; Gesualdo, F.; Russo, L.; Raponi, M. Attitude of Families of Patients with Genetic Diseases to Use m-Health Technologies. Telemed. e-Health 2015, 21, 86–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karisalmi, N.; Kaipio, J.; Lahdenne, P. Improving Patient Experience in a Children’s Hospital: New Digital Services for Chil-dren and Their Families. Stud. Health Technol. Inform. 2018, 247, 935–939. [Google Scholar]

- Luciano, M.; Sampogna, G.; Del Vecchio, V.; Giacco, D.; Mulè, A.; De Rosa, C.; Fiorillo, A.; Maj, M. The family in Italy: Cultural changes and implications for treatment. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 2012, 24, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Vecchio, V.; Luciano, M.; Sampogna, G.; De Rosa, C.; Giacco, D.; Tarricone, I.; Catapano, F.; Fiorillo, A. The role of relatives in pathways to care of patients with a first episode of psychosis. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2015, 61, 631–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmichael, B.; Pembre, M.; Turner, G.; Barnicoat, A. Diagnosis of fragile-X syndrome: The experiences of parents. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 1999, 43 Pt 1, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bultas, M.W.; McMillin, S.E.; Zand, D.H. Reducing Barriers to Care in the Office-Based Health Care Setting for Children With Autism. J. Pediatr. Health Care 2016, 30, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kelleher, B.; Halligan, T.; Garwood, T.; Howell, S.; Martin-O’Dell, B.; Swint, A.; Shelton, L.-A.; Shin, J. Brief Report: Assessment Experiences of Children with Neurogenetic Syndromes: Caregivers’ Perceptions and Suggestions for Improvement. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2020, 50, 1443–1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Implementing Telemedicine Services during COVID-19: Guiding Principles and Considerations for a Stepwise Approach; WHO Regional Office for the Western Pacific: Manila, Philippines, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Visconti, R.M.; Morea, D. Healthcare Digitalization and Pay-For-Performance Incentives in Smart Hospital Project Financing. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- European Parliament and Council. Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of 27 April 2016 on the Protection of Natural Persons with Regard to the Processing of Personal Data and on the Free Movement of Such Data, and Repealing Directive 95/46/EC (General Data Protection Regulation); EC: Brussels, Belgium, 2016; Available online: http://eurlex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32016R0679 (accessed on 17 May 2018).

- World Health Organization. Recommendations on Digital Interventions for Health System Strengthening; Web Supplement 2: Summary of Findings and GRADE Tables; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Turvey, C.; Coleman, M.; Dennison, O.; Drude, K.; Goldenson, M.; Hirsch, P.; Jueneman, R.; Kramer, G.M.; Luxton, D.D.; Maheu, M.M.; et al. ATA Practice Guidelines for Video-Based Online Mental Health Services. Telemed. e-Health 2013, 19, 722–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernard, M.L.; Chaparro, B.S.; Mills, M.M.; Halcomb, C.G. Examining children’s reading performance and preference for different computer-displayed text. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2002, 21, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaidi, S.T.; Marriott, J.L. Barriers and Facilitators to Adoption of a Web-based Antibiotic Decision Support System. South Med. Rev. 2012, 5, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sun, H.-M.; Li, S.-P.; Zhu, Y.-Q.; Hsiao, B. The effect of user’s perceived presence and promotion focus on usability for interacting in virtual environments. Appl. Ergon. 2015, 50, 126–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montemurro, N.; Perrini, P. Will COVID-19 change neurosurgical clinical practice? Br. J. Neurosurg. 2020, 1, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ateriya, N.; Saraf, A.; Meshram, V.P.; Setia, P. Telemedicine and virtual consultation: The Indian perspective. Natl. Med. J. India 2018, 31, 215–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ash, J.S.; Bates, D.W. Factors and Forces Affecting EHR System Adoption: Report of a 2004 ACMI Discussion. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2004, 12, 8–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poon, P.; Hui, E.; Dai, D.; Kwok, T.; Woo, J. Cognitive intervention for community-dwelling older persons with memory problems: Telemedicine versus face-to-face treatment. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2005, 20, 285–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byambasuren, O.; Beller, E.; Glasziou, P. Current Knowledge and Adoption of Mobile Health Apps among Australian General Practitioners: Survey Study. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2019, 7, e13199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Minou, J.; Mantas, J.; Malamateniou, F.; Kaitelidou, D. Health Professionals’ Perception about Big Data Technology in Greece. Acta Inform. Med. 2020, 28, 48–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lapointe, L. Getting physicians to accept new information technology: Insights from case studies. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2006, 174, 1573–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Rathert, C.; Mittler, J.N.; Banerjee, S.; McDaniel, J. Patient-centered communication in the era of electronic health records: What does the evidence say? Patient Educ. Couns. 2017, 100, 50–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arar, N.H.; Wen, L.; McGrath, J.; Steinbach, R.; Pugh, J.A. Communicating about medications during primary care outpatient visits: The role of electronic medical records Inform. Prim. Care 2005, 13, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Huys, Q.J.M.; Maia, T.V.; Frank, M.J. Computational psychiatry as a bridge from neuroscience to clinical applications. Nat. Neurosci. 2016, 19, 404–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Visconti, R.M.; Morea, D. Big Data for the Sustainability of Healthcare Project Financing. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Weiner, J.P. Doctor-patient communication in the e-health era. Isr. J. Health Policy Res. 2012, 1, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Torous, J.B.; Chan, S.R.; Yellowlees, P.M.; Boland, R. To Use or Not? Evaluating ASPECTS of Smartphone Apps and Mobile Technology for Clinical Care in Psychiatry. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2016, 77, e734–e738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sequeira, L.; Battaglia, M.; Perrotta, S.; Merikangas, K.; Strauss, J. Digital Phenotyping with Mobile and Wearable Devices: Advanced Symptom Measurement in Child and Adolescent Depression. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2019, 58, 841–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Functional Requirements | Non-Functional Requirements |

| Guide to the facility Acceptance and registration 1. A feature that enables univocal association of a code to every patient into the system; 2. Authentication of user whenever he/she logs into the system; 3. Enforce automatic logoff. Role and times 1. Two types of users’ accounts: clinicians and families; 2. A feature that enables clinicians to create the agenda of the planned activities of the DH; 3. A feature that enables families to visualize the agenda of fu-ture appointments and the schedules of the DH activities. Procedures 1. A function that enables families to have information to navi-gate through the building and on hospital facilities; 2. A page with informative contents (video cartoons) on the steps for specific instrumental examinations (electroencephalography). | Performance and scalability The software should be an adaptable tool that can be improved in its functions and capacity according to users’ requests and needs. |

| Interoperability The software should be able to communicate with other software. | |

| Portability The software should be able to be used in different hospital contexts and by different users. | |

| Communication and assistance Medical History 1. Different users’ dashboard pages (clinicians, families); 2. A page with a list of anamnestic questions focused on neuro-psychiatric and psychological development; 3. A feature that enables users to explore different sections of the anamnestic questionnaire; 4. A feature that enables users (families) to fill the anamnestic questionnaire; 5. A feature that enables users (clinicians) to visualize and validate anamnestic data provided by families. Patients communications and notifications 1. A push notification service that enables prompt information exchange from clinicians to families about the DH steps and procedures; 2. Pages with educational contents about: (i) neuropsychiatric conditions and treatment; (ii) the DH organization and clinicians’ roles (e.g., psychologists, nurses); 3. A feature that enables clini-cians to associate educational contents to specific users’ account; 4. A feature that enables families to visualize and explore the associated educational contents (patient education). | Privacy and security The software should guarantee adequate privacy and security protections for sensitive data exchanged remotely (compliance with GDPR). |

| Accessibility The software should include different devices for a wide range of users, allowing sufficient response time also for the slowest users. | |

| Diagnostic Survey management 1. A feature that enables remote anamnestic data acquisition by clinicians; 2. A function that enables the automatized conversion of data collected through the anamnestic questionnaire into a text for-mat. Reporting 1. A function that enables accessibility and extraction for statistical analysis through the automatized conversion of data collected into a database. 2. A function that enables clinicians to complete, edit, add, and delete different fields in the resume file for the DH discharge. | Usability The software should be user-friendly, allowing an interaction perceived as effective by the users. It should also re-quire minimal training time for using the system. |

| Supportability | |

The software should be: (i) easy to install and configure: (ii) cost-effective to maintain. | |

| Manageability The software should support system admin in troubleshooting problems. |

| Usability-Caregivers Questionnaire | Strongly Agree | Moderately Agree | Disagree | Missing |

| The explanations provided for the use of Assioma were clear. | 87.5% (21) | 12.5% (3) | - | - |

| I would have preferred more detailed explanation for using Assioma. | 4% (1) | 21% (5) | 75% (18) | - |

| It was easy to perform log-in. | 79% (19) | 17% (4) | - | 4% (1) |

| The graphical interface of the platform was pleasant. | 58% (14) | 42% (10) | - | - |

| The contents of the platform were clear and easy to understand. | 79% (19) | 21% (5) | - | - |

| It was easy to move from one section to another of Assioma for tablet. | 67% (16) | 33% (8) | - | - |

| It was easy to complete the anamnestic questionnaire. | 71% (17) | 29% (7) | - | - |

| It was easy to move from one section to another within Assioma for smartphone. | 62.5% (15) | 29% (7) | - | 8.5% (2) |

| Assioma for tablet was intuitive and easy to navigate. | 75% (18) | 25% (6) | - | - |

| Assioma for smartphone was intuitive and easy to navigate. | 54% (13) | 29.5% (7) | 4% (1) | 12.5% (3) |

| I am satisfied of the font size and style used in Assioma application. | 83.5% (20) | 12.5% (3) | - | 4% (1) |

| Usability-Clinicians Questionnaire | Strongly Agree | Moderately Agree | Disagree | Missing |

| The explanations provided for the use of Assioma were clear. | 100% (6) | - | - | - |

| I would have preferred more detailed explanation for using Assioma. | 83% (5) | 17% (1) | - | - |

| Patients’ registration was easy. | 67% (4) | 33% (2) | - | - |

| The graphical interface of the platform was pleasant. | 83% (5) | 17% (1) | - | - |

| I was satisfied with the font size of Assioma. | 100% (6) | - | - | - |

| The contents were clear and easy to understand. | 100% (6) | - | - | - |

| It was easy to move from one session to another of Assioma for PC. | 50% (3) | 50% (3) | - | - |

| The validation and integration of the medical history questionnaire was easy. | 67% (4) | 33% (2) | - | - |

| Assioma for PC was intuitive and easy to navigate. | 67% (4) | 33% (2) | - | - |

| Satisfaction-Caregivers Questionnaire | Strongly Agree | Moderately Agree | Disagree | Missing |

| Assioma made the Day Hospital experience more comfortable. | 67% (16) | 33% (8) | - | - |

| The Day Hospital notifications were helpful for hospital experience. | 34% (8) | 54% (13) | 4% (1) | 8% (2) |

| The vision of the video cartoon on the Day Hospital procedure was useful. | 42% (10) | 50% (12) | 4% (1) | 4% (1) |

| The vision of the video cartoon on the EEG procedure was useful. | 29% (7) | 50% (12) | 12% (3) | 9% (2) |

| The vision of the information sheets was useful. | 25% (6) | 58% (14) | 4% (1) | 13% (3) |

| Assioma for smartphone was useful. | 21% (5) | 46% (11) | 8% (2) | 25% (6) |

| Assioma improved the communication with clinicians. | 42% (10) | 54% (13) | - | 4% (1) |

| I am globally satisfied of Assioma platform. | 50% (12) | 46% (11) | - | 4% (1) |

| Satisfaction-Clinicians Questionnaire | Strongly Agree | Moderately Agree | Disagree | Missing |

| The digitalization of the anamnestic questionnaire was useful for the clinical practice. | 17% (1) | 83% (5) | - | - |

| The export of the anamnestic questionnaire in text format was useful for the clinical practice. | 83% (5) | 17% (1) | - | - |

| The export of the anamnestic questionnaire in excel format was useful for the clinical practice. | 100% (6) | - | - | - |

| The inclusion of informative contents on neuropsychiatric diseases was useful for the clinical practice. | 83% (5) | 17% (1) | - | - |

| The use of Assioma made the Day Hospital procedure more efficient. | 50% (3) | 50% (3) | - | - |

| Notifications on the Day Hospital activities were useful for the clinical practice. | 33% (2) | 33% (2) | 17% (1) | 17% (1) |

| Assioma improved the communication between patients/parents and clinicians. | 50% (3) | 50% (3) | - | - |

| I am globally satisfied of Assioma platform. | 33% (2) | 67% (4) | - | - |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fucà, E.; Costanzo, F.; Bonutto, D.; Moretti, A.; Fini, A.; Ferraiuolo, A.; Vicari, S.; Tozzi, A.E. Mobile-Health Technologies for a Child Neuropsychiatry Service: Development and Usability of the Assioma Digital Platform. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2758. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18052758

Fucà E, Costanzo F, Bonutto D, Moretti A, Fini A, Ferraiuolo A, Vicari S, Tozzi AE. Mobile-Health Technologies for a Child Neuropsychiatry Service: Development and Usability of the Assioma Digital Platform. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(5):2758. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18052758

Chicago/Turabian StyleFucà, Elisa, Floriana Costanzo, Dimitri Bonutto, Annarita Moretti, Andrea Fini, Alberto Ferraiuolo, Stefano Vicari, and Alberto Eugenio Tozzi. 2021. "Mobile-Health Technologies for a Child Neuropsychiatry Service: Development and Usability of the Assioma Digital Platform" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 5: 2758. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18052758

APA StyleFucà, E., Costanzo, F., Bonutto, D., Moretti, A., Fini, A., Ferraiuolo, A., Vicari, S., & Tozzi, A. E. (2021). Mobile-Health Technologies for a Child Neuropsychiatry Service: Development and Usability of the Assioma Digital Platform. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(5), 2758. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18052758