Effects of a Home Literacy Environment Program on Psychlinguistic Variables in Children from 6 to 8 Years of Age

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

- Participants attended the above-mentioned educational center.

- Participants were enrolled in the first year of elementary education (at the beginning of the program).

- Participants were neither receiving nor had previously received specific reading acceleration programs.

2.2. Instruments

2.2.1. Phonological Awareness

- Phonemic segmentation. Assesses the ability to identify, segment, and manipulate phonemes, isolated or combined. The child must divide the word into parts, eliminating some of the consonants or a complete syllable, or replacing them with others. The test is ended if errors are made in the first four items or following three consecutive errors, with a count taken of the correct answers. The maximum direct score is 8. The validity and reliability of the measure has been demonstrated in the literature, specifically, the test presents a Cronbach’s reliability coefficient of 0.94 [47].

- Rhymes. Assesses the individual’s ability to segment and identify the final group of phonemes in the word. Pairs of words are presented orally and the child must indicate whether or not they rhyme. A count is taken of successful pairings. The maximum direct score is 8. The validity and reliability of the measure has been demonstrated in the literature, specifically, the test presents a reliability coefficient of 0.73 [47].

- Verbal fluency. Assesses the ability to identify the initial phoneme “p” in words from their lexical repertoire, within a given time. The child must name, within one minute, the maximum number of words beginning with “p”, with a count taken of the correct answers. The maximum direct score is 25. The validity and reliability of the measure has been demonstrated in the literature [47].

2.2.2. Decoding and Identification in Reading

- Reading. Assesses the individual’s ability to recognize and identify words from a list. As these words are not inserted into a text, it was decided in our study to name the variable “word reading”. The student must read a set of words, in a given time, with one point counted for each word correctly decoded. The maximum direct score is 120. The validity and reliability of the measure has been demonstrated in the literature [47].

- Reading without meaning. Assesses the individual’s ability to recognize words and pseudowords (such as Norbi, rather than Norgin) inserted into a text. The maximum score is 58; one point is counted for each correct word and two for each pseudoword. Furthermore, if more or less than a minute is taken to complete the task, a half point is penalized or rewarded for each second (up to a maximum of 10 points). It should be noted that the text used in this task (an excerpt from Lewis Carroll’s Jabberwocky in Spanish), despite including elements without meaning, is not without sense. For this reason, in the study, it was decided to name the variable “reading without meaning” and not “without sense”. The validity and reliability of the measure has been demonstrated in the literature [47].

2.2.3. Vocabulary

- Semantic fluency. This measures the breadth of the individual’s vocabulary. The child must name, within one minute, words belonging to the semantic field of animals, with a count taken of correct answers. The maximum direct score is 25. The validity and reliability of the measure has been demonstrated in the literature [47].

- Similarities. Assesses the child’s ability to abstract similarities and make generalizations based on two given concepts. In this test, the student must indicate which characteristics share the meanings of two different words named by the examiner. In total, the test comprises 23 items, to be rated from 0 to 2 depending on the appropriateness of the response. The maximum direct score is 46. The validity and reliability of the measure has been demonstrated in the literature, specifically, the reliability coefficients of the individual subtests range from 0.80 to 0.94, demonstrating high levels of internal consistency [48,49].

- Vocabulary. Assesses the child’s lexical knowledge, conceptual accuracy, and expressive ability. In this test, the student must name a series of visual stimuli and define the words presented in oral form by the assessor. In total, the test comprises 29 items (4 that constitute visual stimuli and 25, verbal stimuli). The maximum direct score is 54. The validity and reliability of the measure has been demonstrated in the literature, specifically, the reliability coefficients of the individual subtests range from 0.80 to 0.94, demonstrating high levels of internal consistency [48,49].

2.2.4. Oral Narrative Comprehension

- Oral comprehension. Assesses the individual’s ability to understand narratives read by the assessor. Following the presentation of each story (two stories are told), four questions are asked, with a count made of the correct answers. The maximum possible number of points is 8. The validity and reliability of the measure has been demonstrated in the literature, specifically, the test presents a Cronbach’s reliability coefficient of 0.67 [35].

2.3. Procedure

2.3.1. Evaluation Phase

2.3.2. Intervention Phase

- Daily reading time: minimum 10 min; maximum 15.

- Read in a quiet place, free from distractions.

- The child must read aloud.

- The adult must be attentive to the reading and make corrections in a positive way when necessary.

- At the end, the adult should ask the child two or three questions about what has been read (for example: Who is the protagonist of the story? Why do they act like this? etc.).

- Fill in the sheet in the booklet each day and enjoy this moment of reading with your child.

2.4. Design and Data Analysis

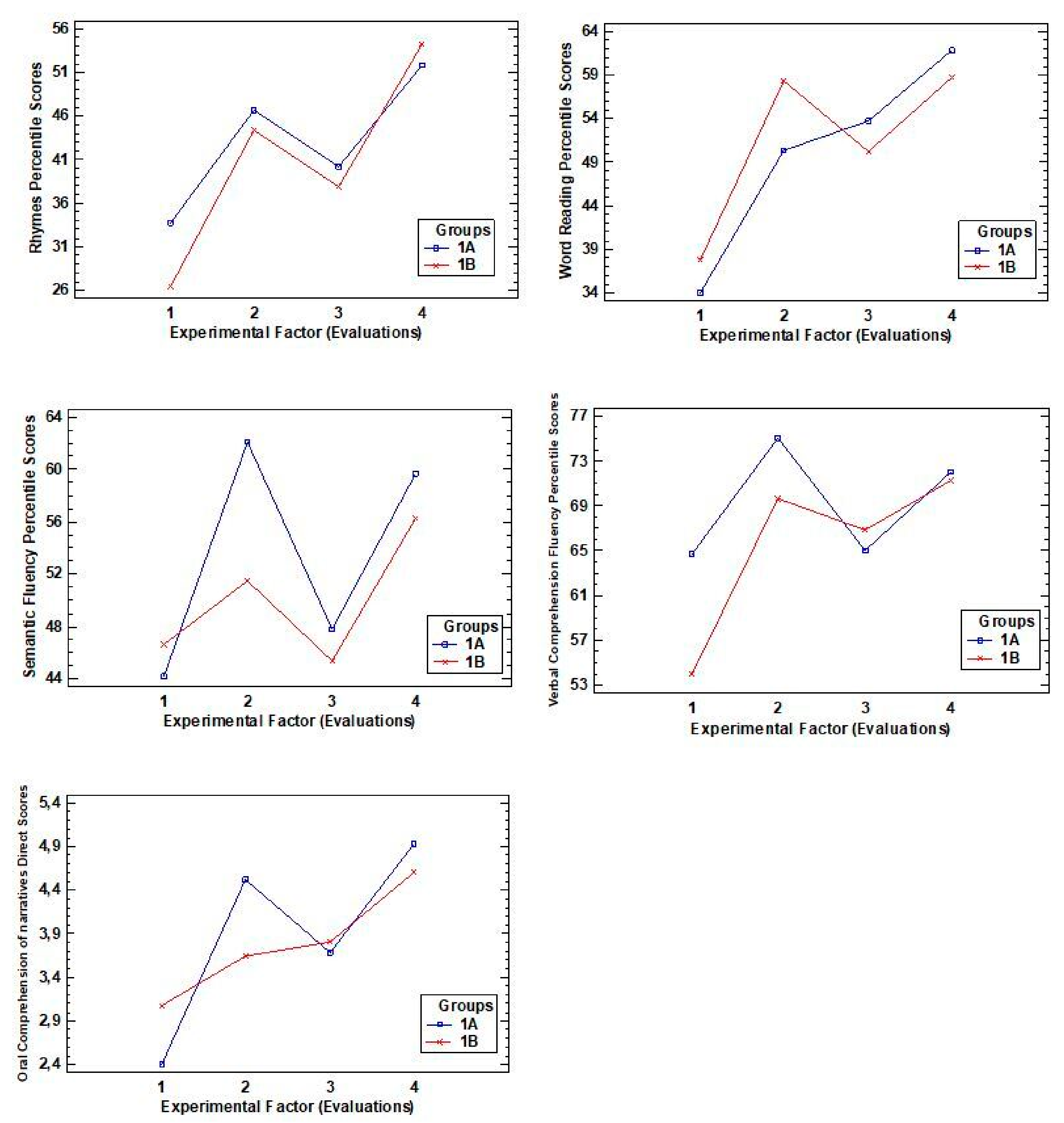

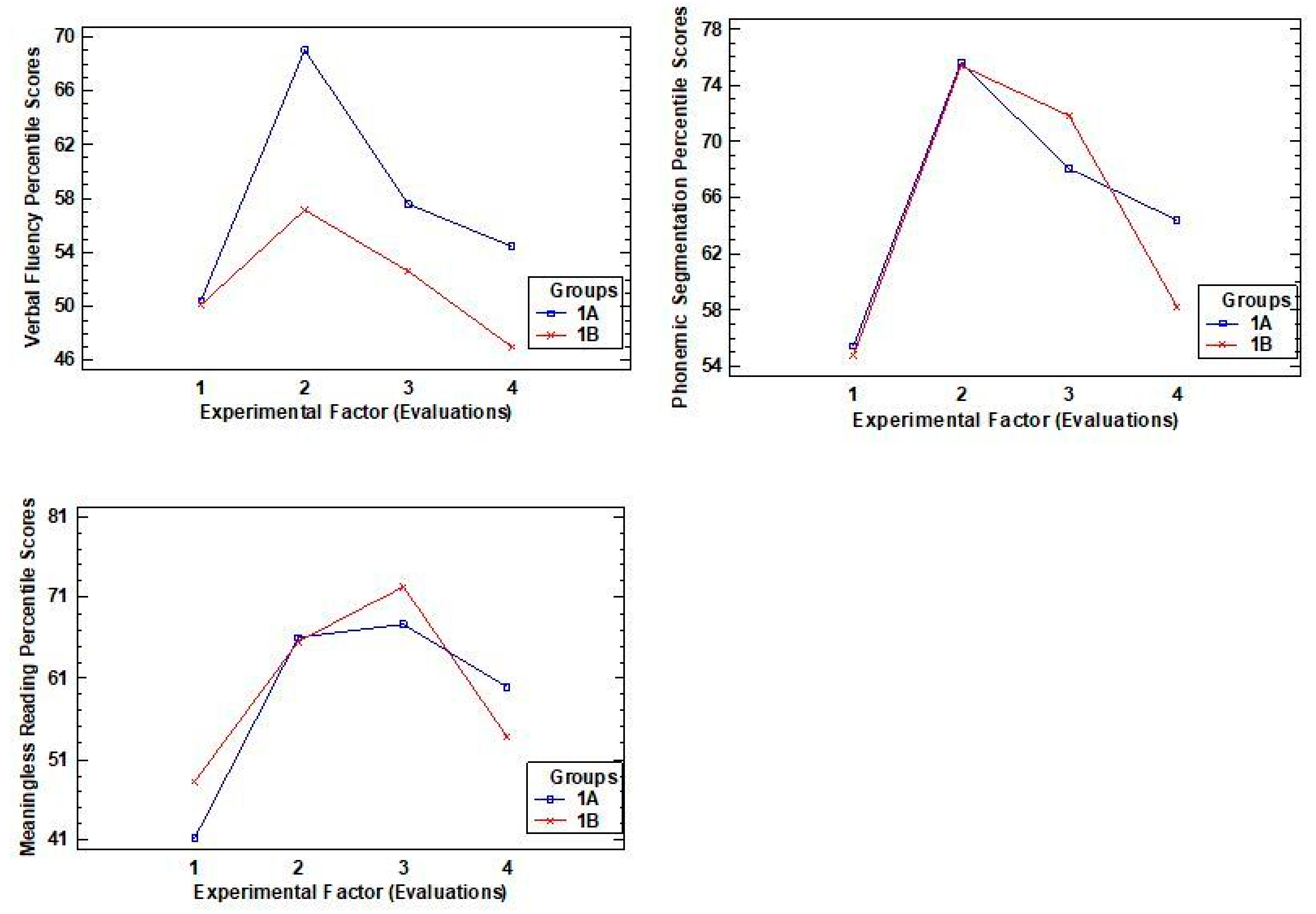

3. Results

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Romero, J.F.; Lavigne, R. Dificultades en el Aprendizaje: Unificación de Criterios Diagnósticos. I. Definición, Características y Tipos, 1st ed.; Junta de Andalucía: Madrid, España, 2005; ISBN 84-689-1108-9. [Google Scholar]

- De Vega, M.; Carreiras, M.; Gutiérrez-Calvo, M.; Alonso-Quecuty, M.L. Lectura y Comprensión. Una Perspectiva Cogniva, 1st ed.; Alianza Editorial: Madrid, España, 1990; ISBN 84-206-6529-0. [Google Scholar]

- Rugerio, J.P.; Guevara, Y. Alfabetización inicial y su desarrollo desde la educación infantil. Revisión del concepto e investigaciones aplicadas. Ocnos Rev. Estud. Sobre Lect. 2015, 25–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kim, S.; Im, H.; Kwon, K.-A. The Role of Home Literacy Environment in Toddlerhood in Development of Vocabulary and Decoding Skills. Child Youth Care Forum 2015, 44, 835–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Higes, R.; Valdehita, S.R. ¿Qué variables determinan el nivel lector de un alumno en el segundo ciclo de Educación Primaria y cuál es su valor diagnóstico? Rev. Iberoam. Diagn. Eval. Psicol. 2014, 1, 31–52. [Google Scholar]

- Valdivieso, L.B. El aprendizaje del lenguaje escrito y las ciencias de la lectura. Un límite entre la psicología cognitiva, las neurociencias y la educación. Límite. Rev. Iberoam. Diagn. Eval. Psicol. 2016, 11, 50–59. [Google Scholar]

- Defior, S.; Serrano, F. La conciencia fonémica, aliada de la adquisición del lenguaje escrito. Rev. Logop. Foniatr. Audiol. 2011, 31, 2–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adrián, J.A.; Alegria, J.; Morais, J. Metaphonological abilities of spanish illiterate adults. Int. J. Psychol. 1995, 30, 329–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fresneda, R.G. Efectos de la lectura compartida y la conciencia fonológica para una mejora en el aprendizaje lector. Rev. Complut. Educ. 2018, 29, 441–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Morais, J.; Cary, L.; Alegria, J.; Bertelson, P. Does awareness of speech as a sequence of phones arise spontaneously? Cognition 1979, 7, 323–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Cabrera, A.M.C.; Villagrán, M.A.; Guzmán, J.I.N. Desarrollo evolutivo de la conciencia fonológica: ¿cómo se relaciona con la competencia lectora posterior? Rev. Investig. Logop. 2016, 6, 22–41. [Google Scholar]

- González-Seijas, R.M.; Cuetos, F.; López-Larrosa, S.; Vilar, J.M. Efectos del entrenamiento en conciencia fonológica y velocidad de denominación sobre la lectura: Un estudio longitudinal. Eff. Fonol. Aware. Namin. Speed Train. Read. 2017, 32, 155–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Andrés-Roqueta, C.; Garcia-Molina, I.; Flores-Buils, R. Association between CCC-2 and Structural Language, Pragmatics, Social Cognition and Executive Functions in Children with Developmental Language Disorder. Children 2021, 8, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niklas, F.; Schneider, W. With a little help: Improving kindergarten children’s vocabulary by enhancing the home literacy environment. Read. Writ. 2014, 28, 491–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Fresneda, R. Efectos de la lectura dialógica en la mejora de la comprensión lectora de estudiantes de Educación Primaria. Rev. Psicodidáct. 2016, 21, 303–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Perfetti, C.A. Reading Ability: Lexical Quality to Comprehension. Sci. Stud. Read. 2007, 11, 357–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strasser, K.; Del Río, F.; Larraín, A. Vocabulary Depth and Breadth: Their Role in Preschoolers’ Story Comprehension. Estud. Psicol. 2013, 34, 221–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerasari, M.; Castrioti, R.; Rodríguez, A.; Casanovas, M.S. El Desarrollo de Habilidades Narrativas y del Vocabulario en Niños Como Parte de los Resultados de un Programa de Alfabetización. In V Congreso Internacional de Investigación de la Facultad de Psicología de la Universidad Nacional de La Plata (La Plata, 2015); SEDICI: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz, M.D.M.M.; Soto, A.T. Hábito lector en estudiantes de primaria: Influencia familiar y del Plan Lector del centro escolar. Rev. Fuentes 2019, 1, 103–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez, J.E. Dislexia en español. Prevalencia e Indicadores Cognitivos, Culturales, Familiares y Biológicos, 1st ed.; Ediciones Pirámide: Madrid, España, 2012; ISBN 978-84-368-2649-4. [Google Scholar]

- Puglisi, M.L.; Hulme, C.; Hamilton, L.G.; Snowling, M.J. The Home Literacy Environment Is a Correlate, but Perhaps Not a Cause, of Variations in Children’s Language and Literacy Development. Sci. Stud. Read. 2017, 21, 498–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, T.; Georgiou, G.K.; Parrila, R.; Kirby, J.R. Examining an Extended Home Literacy Model: The Mediating Roles of Emergent Literacy Skills and Reading Fluency. Sci. Stud. Read. 2018, 22, 273–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiescholek, S.; Hikenmeier, J.; Greiner, C.; Buhl, H.M. Six-year-olds’ perception of home literacy environment and its influence on children’s literacy enjoyment, frequency, and early literacy skills. Read. PSychol. 2018, 39, 41–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sénéchal, M.; Young, L. The effect of family literacy interventions on children’s acquisition of reading from kindergarten to grade 3: A meta-analytic review. Rev. Educ. Res. 2008, 78, 880–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Van Bergen, E.; Van Zuijen, T.; Bishop, D.; De Jong, P.F. Why Are Home Literacy Environment and Children’s Reading Skills Associated? What Parental Skills Reveal. Read. Res. Q. 2016, 52, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgess, S.R. Home literacy environments (HLEs) provided to very young children. Early Child Dev. Care 2010, 181, 445–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, W.; Harris, P.; Sethuraman, S.; Thiruvaiyaru, D.; Pendergraft, E.; Cliett, K.; Cato, V. Empowering Young Children in Poverty by Improving Their Home Literacy Environments. J. Res. Child. Educ. 2016, 30, 211–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, E.T.; Tamis-LeMonda, C.S. Trajectories of the Home Learning Environment Across the First 5 Years: Associations With Children’s Vocabulary and Literacy Skills at Prekindergarten. Child Dev. 2011, 82, 1058–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, L.M. Expanded Manual for the Peabody Vocabulary Test; American Guidance Service: Circle Pines, MI, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Fenson, L.; Dale, P.S.; Reznick, J.S.; Thal, D.; Hartung, J.P.; Pethicks, S.; Reilly, J.S. MacArthur Communicative Development Inventory: Users Guide and Technical Manual; Singular Publishing Company: San Diego, CA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Lonigan, C.; Wagner, R.; Torgeson, J.; Rahotte, C. Preschool Comprehensive Test of Phonological and Print Processing (Pre-CTOPPP); Department of Psychology, Florida State University: Tallahassee, FL, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Van Steensel, R.; McElvany, N.; Kurvers, J.; Herppich, S. How Effective Are Family Literacy Programs? Rev. Educ. Res. 2011, 81, 69–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De La Rie, S.; Van Steensel, R.; Van Gelderen, A. Implementation quality of family literacy programmes: A review of literature. Rev. Educ. 2016, 5, 91–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mora-Figueroa, J.; Galán, A.; López-Jurado, M. Efectos de la implicación familiar en estudiantes con riesgo de dificultad lectora. Ocnos Rev. Estud. Sobre Lect. 2016, 15, 7–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cuetos, F.; Rodríguez, B.; Ruano, B.; Arribas, D. Batería de Evaluación de Los Procesos Lectores Revisada, PROLEC-R, 2nd ed.; TEA Ediciones: Madrid, España, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kiese-Himmel, C. AWST-R—Aktiver Wortschatztest Für 3- Bis 5-Jährige Kinder [AWST-R—Active Vocabulary Test for 3- to 5-Year-Old Children]; Hogrefe: Göttingen, Germany, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Burgemeister, B.; Blum, L.; Lorge, J. Columbia Mental Maturity Scale; Harcourt Brace Jovanovich: New York, NY, USA, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Niklas, F.; Schneider, W. Intervention in the home literacy environment and kindergarten children’s vocabulary and phonological awareness. First Lang. 2017, 37, 433–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niklas, F.; Wirth, A.; Guffler, S.; Drescher, N.; Ehmig, S.C. The Home Literacy Environment as a Mediator Between Parental Attitudes Toward Shared Reading and Children’s Linguistic Competencies. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silinskas, G.; Sénéchal, M.; Torppa, M.; Lerkkanen, M.-K. Home Literacy Activities and Children’s Reading Skills, Independent Reading, and Interest in Literacy Activities From Kindergarten to Grade 2. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. PISA 2015 Results (Volume I); OECD: Paris, France, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. PISA 2015 Results (Volume II); OECD: Paris, France, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. PISA 2015 Results (Volume IV); OECD: Paris, France, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. PISA 2015 Results (Volume III); OECD: Paris, France, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. PISA 2015 Results (Volume V); OECD: Paris, France, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- INEE Publicaciones-Ministerio de Educación y Formación Profesional; INEE: Madrid, España, 2017.

- Fawcett, A.J.; Nicholson, R.I. DST-J. Test Para La Detección de La Dislexia en Niños; TEA Ediciones: Madrid, España, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Weschsler, D. Escala de Wechsler de Inteligencia (WISC-V); Person Education: Madrid, España, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Pearson Clinical WISC-V. Efficacy Research Report; Pearson Clinical: Madrid, España, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Field, A. Discovering Stadistics Using SPSS, 3rd ed.; SAGE: Riverside, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick, B.G.; Fidell, L.S. Experimental Designs Using ANOVA; Thomson, Bropkc, Cole.: Belmont, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- De La Calle, A.M.; Guzmán-Simón, F.; García-Jiménez, E. El conocimiento de las grafías y la secuencia de aprendizaje de los grafemas en español: Precursores de la lectura temprana. Rev. Psicodidáct. 2018, 23, 128–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, K.; Sandilos, L.E.; Hammer, C.S.; Sawyer, B.E.; Méndez, L.I. Relations Among the Home Language and Literacy Environment and Children’s Language Abilities: A Study of Head Start Dual Language Learners and Their Mothers. Early Educ. Dev. 2016, 27, 478–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Senechal, M.; Lefevre, J.-A. Parental Involvement in the Development of Children’s Reading Skill: A Five-Year Longitudinal Study. Child Dev. 2002, 73, 445–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burgess, S.R. The influence of speech perception, oral language ability, the home literacy environment, and pre-reading knowledge on the growth of phonological sensitivity: A one-year longitudinal investigation. Read. Writ. 2002, 15, 709–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Instrument | Task |

|---|---|---|

| Phonological awareness | DST-J | Phonemic segmentation, rhymes, and verbal fluency |

| Reading decoding | DST-J | Reading and reading without meaning |

| Vocabulary | DST-J | Semantic fluency and vocabulary |

| WISC-V | Verbal Comprehension Index: Similarities and Vocabulary Subtests | |

| Oral narrative comprehension | PROLEC-R | Oral comprehension |

| Variables | Group Factor p-Value | Experimental Factor p-Value | Interaction between Factors p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phonological awareness | Verbal fluency | 0.2054 | 0.0172 | 0.6292 |

| Rhymes | 0.4831 | 0.0000 | 0.6436 | |

| Phonetic segmentation | 0.8652 | 0.0000 | 0.5783 | |

| Reading decoding | Word reading | 0.8144 | 0.0000 | 0.1635 |

| Reading without meaning | 0.7403 | 0.0000 | 0.2145 | |

| Vocabulary | Semantic fluency | 0.5367 | 0.0101 | 0.5861 |

| Verbal comprehension | 0.3717 | 0.0012 | 0.3261 | |

| Oral narrative comprehension | Oral narrative comprehension | 0.8071 | 0.0000 | 0.0228 |

| Phonological awareness | Rhymes percentile scores | Evaluation | Mean | Standard Error | 95% Confidence Interval | |

| 1 | 30.0577 | 2.65973 | 24.8023 | 35.3131 | ||

| 2 | 45.5192 | 2.65973 | 40.2639 | 50.7746 | ||

| 3 | 39.0769 | 2.65973 | 33.8215 | 44.3323 | ||

| 4 | 53.0 | 2.65973 | 47.7446 | 58.2554 | ||

| Verbal fluency percentile scores | Evaluation | Mean | Standard error | 95% Confidence interval | ||

| 1 | 50.3077 | 3.17176 | 44.0406 | 56.5748 | ||

| 2 | 63.0769 | 3.17176 | 56.8098 | 69.344 | ||

| 3 | 55.0962 | 3.17176 | 48.829 | 61.3633 | ||

| 4 | 50.7115 | 3.17176 | 44.4444 | 56.9787 | ||

| Phonemic segmentation percentile scores | Evaluation | Mean | Standard error | 95% Confidence interval | ||

| 1 | 55.0769 | 2.52057 | 50.0965 | 60.0573 | ||

| 2 | 75.4808 | 2.52057 | 70.5004 | 80.4612 | ||

| 3 | 69.9808 | 2.52057 | 65.0004 | 74.9612 | ||

| 4 | 61.3462 | 2.52057 | 56.3657 | 66.3266 | ||

| Reading decoding | Word reading percentile scores | Evaluation | Mean | Standard error | 95% Confidence interval | |

| 1 | 35.9074 | 2.13549 | 31.6892 | 40.1256 | ||

| 2 | 54.2963 | 2.13549 | 50.0781 | 58.5145 | ||

| 3 | 51.963 | 2.13549 | 47.7448 | 56.1812 | ||

| 4 | 60.2778 | 2.13549 | 56.0596 | 64.496 | ||

| Reading without meaning percentile scores | Evaluation | Mean | Standard error | 95% Confidence interval | ||

| 1 | 44.7778 | 2.38512 | 40.0665 | 49.4891 | ||

| 2 | 65.8148 | 2.38512 | 61.1035 | 70.5261 | ||

| 3 | 69.963 | 2.38512 | 65.2516 | 74.6743 | ||

| 4 | 56.9444 | 2.38512 | 52.2331 | 61.6558 | ||

| Vocabulary | Semantic fluency percentile scores | Evaluation | Mean | Standard error | 95% Confidence interval | |

| 1 | 45.4038 | 3.34417 | 38.7961 | 52.0116 | ||

| 2 | 56.8077 | 3.34417 | 50.1999 | 63.4155 | ||

| 3 | 46.5769 | 3.34417 | 39.9691 | 53.1847 | ||

| 4 | 57.9615 | 3.34417 | 51.3538 | 64.5693 | ||

| Verbal comprehension fluency percentile scores | Evaluation | Mean | Standard error | 95% Confidence interval | ||

| 1 | 59.3077 | 2.56274 | 54.2439 | 64.3714 | ||

| 2 | 72.3269 | 2.56274 | 67.2632 | 77.3907 | ||

| 3 | 65.9423 | 2.56274 | 60.8786 | 71.0061 | ||

| 4 | 71.6538 | 2.56274 | 66.5901 | 76.7176 | ||

| Oral narrative comprehension | Oral narrative comprehension direct scores | Evaluation | Mean | Standard error | 95% Confidence interval | |

| 1 | 2.74 | 0.182726 | 2.37883 | 3.10117 | ||

| 2 | 4.08 | 0.182726 | 3.71883 | 4.44117 | ||

| 3 | 3.74 | 0.182726 | 3.37883 | 4.10117 | ||

| 4 | 4.76 | 0.182726 | 4.39883 | 5.12117 | ||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Romero-González, M.; Lavigne-Cerván, R.; Sánchez-Muñoz de León, M.; Gamboa-Ternero, S.; Juárez-Ruiz de Mier, R.; Romero-Pérez, J.F. Effects of a Home Literacy Environment Program on Psychlinguistic Variables in Children from 6 to 8 Years of Age. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3085. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18063085

Romero-González M, Lavigne-Cerván R, Sánchez-Muñoz de León M, Gamboa-Ternero S, Juárez-Ruiz de Mier R, Romero-Pérez JF. Effects of a Home Literacy Environment Program on Psychlinguistic Variables in Children from 6 to 8 Years of Age. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(6):3085. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18063085

Chicago/Turabian StyleRomero-González, Marta, Rocío Lavigne-Cerván, Marta Sánchez-Muñoz de León, Sara Gamboa-Ternero, Rocío Juárez-Ruiz de Mier, and Juan Francisco Romero-Pérez. 2021. "Effects of a Home Literacy Environment Program on Psychlinguistic Variables in Children from 6 to 8 Years of Age" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 6: 3085. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18063085