The Performance Implication of Corporate Social Responsibility: The Moderating Role of Employee’s Prosocial Motivation

Abstract

1. Introduction

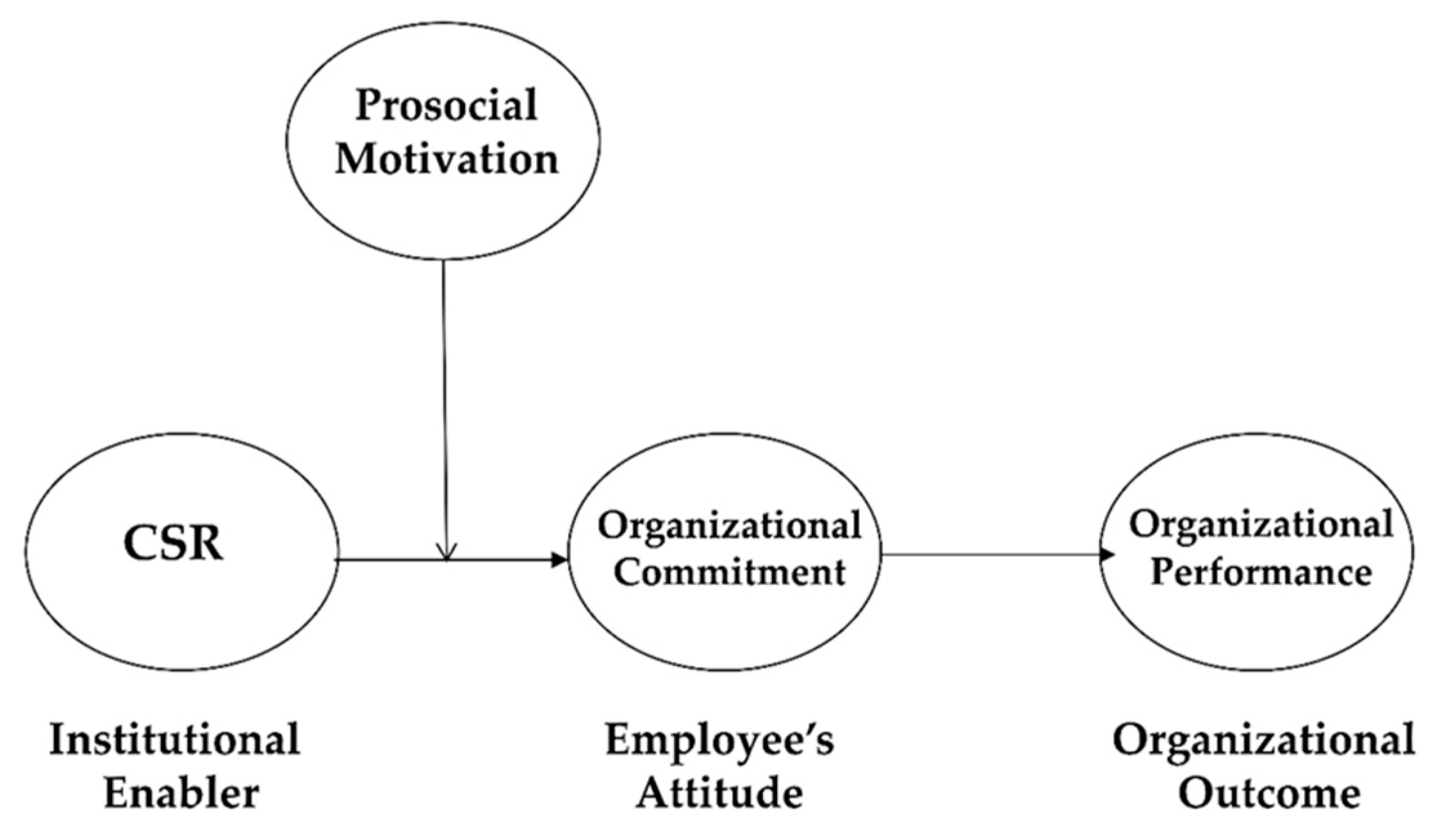

2. Theory and Hypotheses

2.1. CSR and Organizational Commitment

2.2. OC and OP

2.3. The Mediating Effect of OC in an Association between CSR and OP

2.4. The Moderating Effect of Prosocial Motivation in the CSR–OC Link

3. Method

3.1. Data Gathering

3.2. Measures

3.2.1. Corporate Social Responsibility (Time Point 1, Gathered from Employees)

3.2.2. Organizational Commitment (Time Point 2, Collected from Employees)

3.2.3. Organizational Performance (Time Point 3, Gathered from the Human Resource Management Director of Each Company)

3.2.4. Prosocial Motivation (Time Point 1, Collected from Employees)

3.2.5. Control Variables

3.3. Analytical Strategy

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

4.2. Measurement Model

4.3. Structural Model

4.3.1. Results of Mediation Analysis

4.3.2. Results of Moderation Analysis

4.4. Bootstrapping

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Practical Implications

5.3. Limitations and Suggestions for Future Studies

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, Z.; Minor, D.B.; Wang, J.; Yu, C. A learning curve of the market: Chasing alpha of socially responsible firms. J. Econ. Dyn. Contr. 2019, 109, 103772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, C.S.; Chiu, C.J.; Yang, C.F.; Pai, D.P. The Effects of Corporate Social Responsibility on Brand Performance: The Mediating Effect of Industrial Brand Equity and Corporate Reputation. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 95, 457–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlitzky, M.; Schmidt, F.L.; Rynes, S.L. Corporate Social and Financial Performance: A Meta-Analysis. Organ. Stud. 2003, 24, 403–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeidi, S.P.; Sofian, S.; Saeidi, P.; Saeidi, S.P.; Saaeidi, S.A. How does corporate social responsibility contribute to firm financial performance? The mediating role of competitive advantage, reputation, and customer satisfaction. J. Bus. Res. 2015, 68, 341–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McWilliams, A.; Siegel, D. Corporate Social Responsibility and Financial Performance: Correlation or Misspecification? Strateg. Manag. J. 2000, 21, 603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, M.; Garcia, A.; Rodriguez, L. Sustainable development and corporate performance: A study based on the Dow Jones Sustainability Index. J. Bus. Ethics 2007, 75, 285–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, C.W.; Yang, M.L. The Effect of Corporate Social Performance on Financial Performance: The Moderating Effect of Ownership Concentration. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 123, 171–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gond, J.-P.; Moser, C. Critical essay: The reconciliation of fraternal twins: Integrating the psychological and sociological approaches to ‘micro’ corporate social responsibility. Hum. Relat. 2021, 74, 5–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babu, N.; De Roeck, K.; Raineri, N. Hypocritical organizations: Implications for employee social responsibility. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 114, 376–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguinis, H.; Glavas, A. On corporate social responsibility, sensemaking, and the search for meaningfulness through work. J. Manag. 2019, 45, 1057–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguinis, H.; Villamor, I.; Gabriel, K.P. Understanding employee responses to COVID-19: A behavioral corporate social responsibility perspective. Manag. Res. J. Iberoam. Acad. Manag. 2020, 18, 421–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, D.A.; Newman, A.; Shao, R.; Cooke, F.L. Advances in employee-focused micro-level research on corporate social responsibility: Situating new contributions within the current state of the literature. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 157, 293–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguinis, H.; Glavas, A. What we Know and Don’t Know about Corporate Social Responsibility: A Review and Research Agenda. J. Manag. 2012, 38, 932–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Chen, S.; Chiu, C.; Lee, W. Understanding purchasing intention during product harm crises: Moderating effects of perceived corporate ability and corporate social responsibility. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 102, 455–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupp, D.E.; Mallory, D.B. Corporate social responsibility: Psychological, person-centric, and progressing. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2015, 2, 211–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A.B. Corporate social responsibility. Bus. Soc. 1999, 38, 268–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waddock, S.A.; Graves, S.B. The Corporate Social Performance-Financial Performance Link. Strateg. Manag. J. 1997, 18, 303–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmeli, A.; Gilat, G.; Waldman, D.A. The role of perceived organizational performance in organizational identification, adjustment and job performance. J. Manag. Stud. 2007, 44, 972–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, D.A.; Newman, D.A.; Roth, P.L. How important are job attitudes? Meta-analytic comparisons of integrative behavioral outcomes and time sequences. Acad. Manag. J. 2006, 49, 305–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, W.R. Institutions and Organizations; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, N.J.; Meyer, J.P. The Measurement and Antecedents of Affective, Continuance and Normative Commitment to the Organization. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 1990, 63, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J.P.; Allen, N.J. Commitment in the Workplace: Theory, Research, and Application (Advanced Topics in Organizational Behavior); Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Brammer, S.; Millington, A.; Rayton, B. The Contribution of Corporate Social Responsibility to Organizational Commitment. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2007, 18, 1701–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, O.; Payaud, M.; Merunka, D.; Valette-Florence, P. The impact of corporate social responsibility on organizational commitment: Exploring multiple mediation mechanisms. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 125, 563–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rego, A.; Leal, S.; Cunha, M.P.; Faria, J.; Pinho, C. How the perceptions of five dimensions of corporate citizenship and their inter-inconsistencies predict affective commitment. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 94, 107–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stites, J.P.; Michael, J.H. Organizational Commitment in Manufacturing Employees: Relationships with Corporate Social Performance. Bus. Soc. 2011, 50, 50–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turker, D. How Corporate Social Responsibility Influences Organizational Commitment. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 89, 189–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitener, E.M.; Brodt, S.E.; Korsgaard, M.A.; Jon, M.W. Managers as initiators of trust: An exchange relationship framework for understanding managerial trustworthy behavior. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1998, 23, 513–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, M. In whom we trust: Group membership as an affective context for trust development. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2001, 26, 377–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper-Hakim, A.; Viswesvaran, C. The Construct of Work Commitment: Testing an Integrative Framework. Psychol. Bull. 2005, 131, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathieu, J.E.; Zajac, D.M. A Review and Meta-Analysis of the Antecedents, Correlates, and Consequences of Organizational Commitment. Psychol. Bull. 1990, 108, 171–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J.P.; Stanley, D.J.; Herscovitch, L.; Topolnytsky, L. Affective, Continuance, and Normative Commitment to the Organization: A Meta-Analysis of Antecedents, Correlates, and Consequences. J. Vocat. Behav. 2002, 61, 20–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riketta, M. The causal relation between job attitudes and performance: A meta-analysis of panel studies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2008, 93, 472–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wright, T.A.; Bonett, D.G. The moderating effects of employee tenure on the relation between organizational commitment and job performance: A meta-analysis. J. Appl. Psychol. 2002, 87, 1183–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batson, C.D. Prosocial motivation: Is it ever truly altruistic? In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology; Berkowitz, L., Ed.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1987; Volume 20, pp. 65–122. [Google Scholar]

- Grant, A.M. Does intrinsic motivation fuel the prosocial fire? Motivational synergy in predicting persistence, performance, and productivity. J. Appl. Psychol. 2008, 93, 48–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatman, J.A. Improving international organizational research: A model of person–organization fit. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 14, 333–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristof, A.L. Person–organization fit: An integrative review of its conceptualizations, measurement, and implication. Pers. Psychol. 1996, 49, 1–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristof-Brown, A.L.; Zimmerman, R.D.; Johnson, E.C. Consequences of individuals’ fit at work: A meta-analysis of person–job, person–organization, person–group, and person–supervisor fit’. Pers. Psychol. 2005, 58, 281–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burt, R.S. Social Contagion and Innovation: Cohesion versus Structural Equivalence. Am. J. Sociol. 1987, 92, 1287–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, P.M.; Kehoe, R.R. Organizational-level antecedents and consequences of commitment. In Commitment in Organizations: Accumulated Wisdom and New Directions; Klein, H.J., Becker, T.E., Meyer, J.P., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 285–307. [Google Scholar]

- Ostroff, C. The relationship between satisfaction, attitudes, and performance: An organizational level analysis. J. Appl. Psychol. 1992, 77, 963–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrzesniewski, A.; Dutton, J.E.; Debebe, G. Interpersonal Sensemaking and the Meaning of Work. Res. Organ. Behav. 2003, 25, 93–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, S.K.; Atkins, P.W.; Axtell, C.M. Building Better Workplaces through Individual Perspective Taking: A Fresh Look at a Fundamental Human Process. In International Review of Industrial and Organizational Psychology; Hodgkinson, G.P., Ford, J.K., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 2008; Volume 23. [Google Scholar]

- Latham, G.P.; Pinder, C.C. Work motivation theory and research at the dawn of the twenty-first century. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2005, 56, 495–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, T.R.; Daniels, D. Motivation. In Handbook of Psychology, Vol. 12: Industrial and Organizational Psychology; Borman, W.C., Ilgen, D.R., Klimoski, R.J., Eds.; John Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2003; pp. 225–254. [Google Scholar]

- Turker, D. Measuring Corporate Social Responsibility: A Scale Development Study. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 85, 411–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.J.; Nurunnabi, M.; Kim, T.H.; Kim, T.J. Doing Good Is Not Enough, You Should Have Been Authentic: The Mediating Effect of Organizational Identification, and Moderating Effect of Authentic Leadership between CSR and Performance. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, A.M.; Sumanth, J.J. Mission possible? The performance of prosocially motivated employees depends on manager trustworthiness. J. Appl. Psychol. 2009, 94, 927–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson, S.E.; Joshi, A.; Erhardt, N.L. Recent research on teams and organizational diversity: SWOT analysis and implications. J. Manag. 2003, 29, 801–830. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, K.G.; Smith, K.A.; Olian, J.D.; Sims, H.P.; O’Bannon, D.P.; Scully, J.A. Top management team demography and process: The role of social integration and communication. Adm. Sci. Q. 1994, 39, 412–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Structural Equation Modeling in Practice: A Review and Recommended Two-Step Approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, M.W.; Cudeck, R. Alternative Ways of Assessing Model Fit; Sage: New York, NY, USA, 1993; Volume 154, p. 136. [Google Scholar]

- Shrout, P.E.; Bolger, N. Mediation in Experimental and Nonexperimental Studies: New Procedures and Recommendations. Psychol. Methods 2002, 7, 422–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brace, N.; Kemp, R.; Snelgar, R. SPSS for Psychologists: A Guide to Data Analysis Using SPSS for Windows, 2nd ed.; Palgrave: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Staw, B.M. Dressing up like an organization: When psychological theories can explain organizational action. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 805–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eberle, D.; Berens, G.; Li, T. The impact of interactive corporate social responsibility communication on corporate reputation. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 118, 731–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, Y.H.; Sung, S.Y.; Choi, J.N.; Kim, M.S. Top management ethical leadership and firm performance: Mediating role of ethical and procedural justice climate. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 129, 43–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chun, J.S.; Shin, Y.; Choi, J.N.; Kim, M.S. How does corporate ethics contribute to firm financial performance? The role of collective organizational commitment and organizational citizenship behavior. J. Manag. 2013, 39, 853–877. [Google Scholar]

- Arnold, D.F.; Bernardi, R.A.; Neidermeyer, P.E.; Schmee, J. The effect of country and culture on perceptions of appropriate ethical actions prescribed by codes of conduct: A Western European perspective among accountants. J. Bus. Ethics 2007, 70, 327–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenbeiss, S.A. Re-thinking ethical leadership: An interdisciplinary integrative approach. Leadersh. Q. 2012, 23, 791–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, S.D.; Dunford, B.B.; Boss, A.D.; Boss, R.W.; Angermeier, I. Corporate social responsibility and the benefits of employee trust: A cross-disciplinary perspective. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 102, 29–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coles, J.L.; Li, Z.F. An Empirical Assessment of Empirical Corporate Finance. 2019. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=1787143 (accessed on 9 June 2019).

- Li, F.; Morris, T.; Young, B. The Effect of Corporate Visibility on Corporate Social Responsibility. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.M.; Park, S.Y.; Lee, H.J. Employee perception of CSR activities: Its antecedents and consequences. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 1716–1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collier, J.; Esteban, R. Corporate social responsibility and employee commitment. Bus. Ethics Eur. Rev. 2007, 16, 19–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | Percent |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Male | 48.3% |

| Female | 51.7% |

| Age (years) | |

| 20–29 | 20.9% |

| 30–39 | 24.8% |

| 40–49 | 26.8% |

| 50–59 | 27.5% |

| Education | |

| Below high school | 14.2% |

| Community college | 19.5% |

| Bachelor’s degree | 58.6% |

| Master’s degree or higher | 7.6% |

| Work type | |

| Office workers | 63.2% |

| Administrative positions | 19.2% |

| Sales and marketing | 5.9% |

| Manufacturing | 5.3% |

| Education | 1.7% |

| Others | 4.6% |

| Position | |

| Staff | 28.5% |

| Assistant manager | 25.5% |

| Manager or deputy general manager | 29.8% |

| Department/general manager or director and above | 16.2% |

| Tenure (months) | |

| Below 50 | 52.3% |

| 50–100 | 18.2% |

| 100–150 | 15.6% |

| 150–200 | 4.6% |

| 200–250 | 4.3% |

| Above 250 | 5.0% |

| Firm size | |

| Fewer than 50 members | 45.7% |

| 50–99 members | 12.3% |

| 100–299 members | 16.2% |

| 300–499 members | 7.0% |

| More than 500 members | 18.9% |

| Industry Type | |

| Manufacturing | 24.2% |

| Services | 14.2% |

| Construction | 12.9% |

| Information services and telecommunications | 10.3% |

| Education | 9.3% |

| Health and welfare | 8.6% |

| Public service and administration | 7.3% |

| Financial/insurance | 4.0% |

| Others | 9.2% |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Position_T2 | - | |||||||

| 2. Tenure (months) _T2 | 0.32 ** | - | ||||||

| 3. Education_T2 | 0.14 * | −0.01 | - | |||||

| 4. Firm size_T2 | −0.03 | 0.25 ** | 0.18 ** | - | ||||

| 5. Industry type_T2 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.07 | −0.10 | - | |||

| 6. CSR_T1 | 0.15 * | 0.21 ** | −0.02 | 0.23 ** | 0.03 | - | ||

| 7. Prosocial Motivfation_T1 | 0.12 * | 0.10 | 0.11 | 0.01 | 0.06 | 0.29 ** | - | |

| 8. OC_T2 | 0.25 * | 0.19* | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.44 ** | 0.26 ** | - |

| 9. Organizational performance_T3 | 0.08 | 0.06 | −0.11 | 0.02 | 0.14 * | 0.33 ** | 0.12 * | 0.47 ** |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kim, M.-J.; Kim, B.-J. The Performance Implication of Corporate Social Responsibility: The Moderating Role of Employee’s Prosocial Motivation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3128. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18063128

Kim M-J, Kim B-J. The Performance Implication of Corporate Social Responsibility: The Moderating Role of Employee’s Prosocial Motivation. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(6):3128. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18063128

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Min-Jik, and Byung-Jik Kim. 2021. "The Performance Implication of Corporate Social Responsibility: The Moderating Role of Employee’s Prosocial Motivation" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 6: 3128. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18063128

APA StyleKim, M.-J., & Kim, B.-J. (2021). The Performance Implication of Corporate Social Responsibility: The Moderating Role of Employee’s Prosocial Motivation. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(6), 3128. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18063128