Does Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program Reduce Food Insecurity among Households with Children? Evidence from the Current Population Survey

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Conceptual Framework

2.2. The Econometric Procedure

3. Data and Sample

3.1. Food Insecurity and SNAP Participation Measurements

3.2. Identification Variables

3.3. Socio-Demographic Variables

4. Results and Discussion

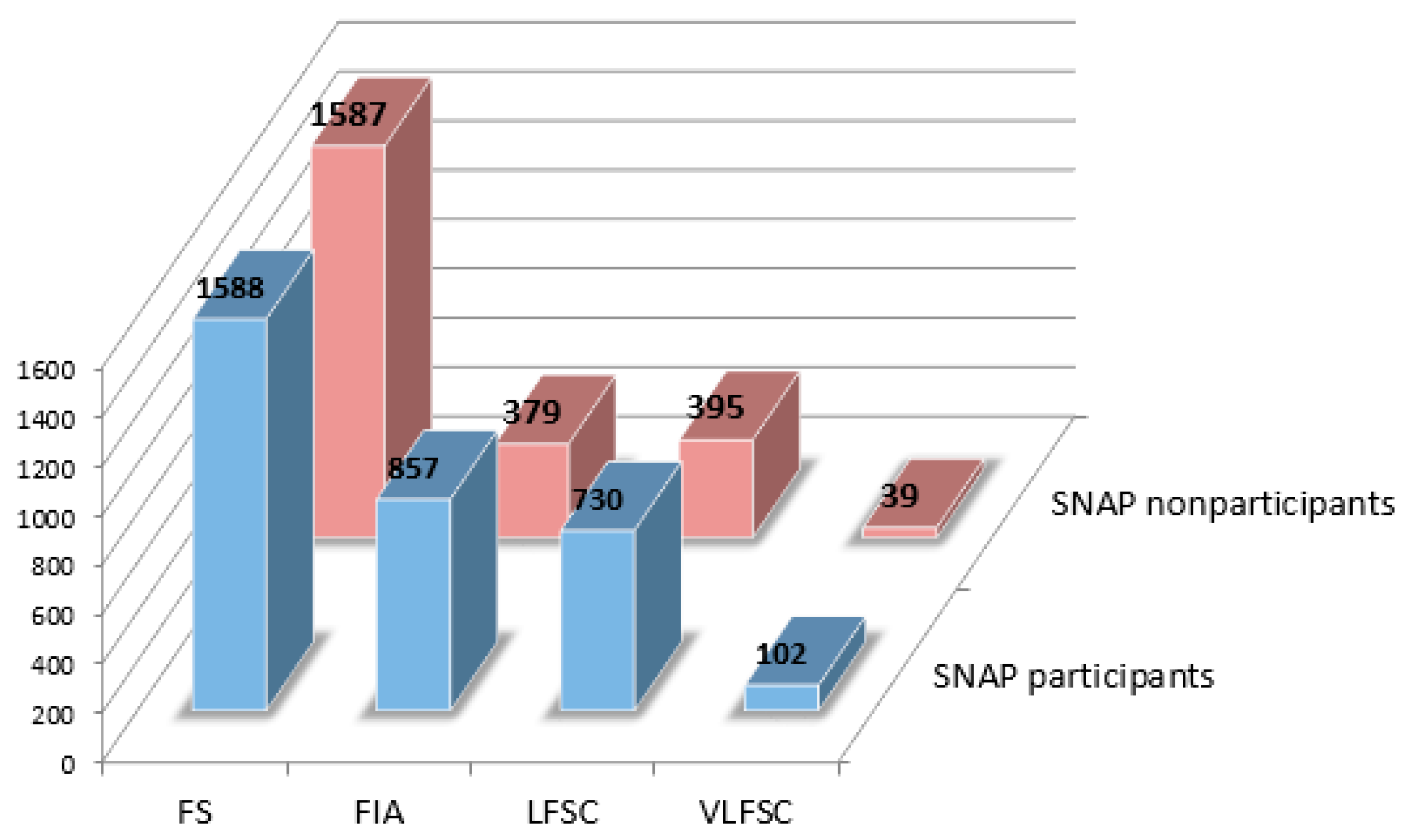

4.1. Characteristics of Sample

4.2. ML Estimates of Recursive System

4.3. Treatment Effects of SNAP Participation on Food Insecurity

4.4. Marginal Effects on Probability of SNAP Participation

4.5. Marginal Effects on Probabilities of FI Categories

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Variable | SNAP Participation | Food Insecure |

|---|---|---|

| Latent SNAP | −0.307 (0.125) ** | |

| BBCE | 0.194 (0.041) *** | |

| Simplified reporting | 0.220 (0.062) *** | |

| Vehicle test | 0.066 (0.055) | |

| Year 2009 | −0.159 (0.047) *** | 0.016 (0.052) |

| Year 2010 | −0.036 (0.045) | −0.031 (0.039) |

| Age/10 | −0.207 (0.025) *** | −0.015 (0.037) |

| Male | 0.028 (0.046) | −0.072 (0.043) * |

| HW household | −0.447 (0.126) *** | −0.212 (0.121) * |

| <High school | 0.005 (0.049) | 0.050 (0.042) |

| Some college | −0.023 (0.051) | 0.028 (0.045) |

| College | −0.213 (0.056) *** | −0.228 (0.053) *** |

| Employed | 0.163 (0.072) ** | 0.116 (0.064) * |

| Unemployed | 0.131 (0.061) ** | 0.192 (0.050) *** |

| Work hours/10 | −0.140 (0.018) *** | −0.070 (0.022) *** |

| Income | −0.346 (0.022) *** | −0.189 (0.042) *** |

| HH size | 0.108 (0.019) *** | 0.042 (0.021) ** |

| Children | 0.071 (0.022) *** | 0.072 (0.021) *** |

| Hispanic | −0.281 (0.047) *** | −0.079 (0.056) |

| White | −0.068 (0.054) | 0.052 (0.048) |

| Other race | −0.009 (0.081) | 0.182 (0.069) *** |

| MSA | −0.101 (0.045) ** | 0.035 (0.044) |

| South | −0.001 (0.054) | 0.021 (0.045) |

| Northeast | 0.091 (0.067) | 0.044 (0.062) |

| Midwest | 0.096 (0.057) * | −0.042 (0.055) |

| Married | 0.010 (0.126) | 0.052 (0.107) |

| Separated | 0.002 (0.056) | 0.035 (0.049) |

| More money | 0.206 (0.039) *** | 0.912 (0.048) *** |

| Constant | 1.112 (0.129) *** | −0.280 (0.245) |

| Thresholds | ||

| ξ1 | 0.623 (0.047) *** | |

| ξ2 | 1.813 (0.133) *** | |

| Error correlation () | 0.479 (0.114) *** | |

| Log likelihood | −8776.7229 |

References

- U.S. Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service (USDA-FNS). Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP). 2021. Available online: https://www.fns.usda.gov/snap/supplemental-nutrition-assistance-program (accessed on 26 February 2021).

- U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service (USDA-ERS). Food Security in the U.S.: Overview. 2021. Available online: https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/food-nutrition-assistance/food-security-in-the-us/key-statistics-graphics/#foodsecure (accessed on 26 February 2021).

- U.S. Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service (USDA-FNS). SNAP Data Tables: National Level Annual Summary. 2021. Available online: https://www.fns.usda.gov/pd/supplemental-nutrition-assistance-program-snap (accessed on 26 February 2021).

- De Cuba, S.E.; Chilton, M.; Bovell-Ammon, A.; Knowles, M.; Coleman, S.M.; Black, M.M.; Cook, J.T.; Cutts, D.B.; Casey, P.H.; Heeren, T.C.; et al. Loss of SNAP is Associated with Food Insecurity and Poor Health in Working Families with Young Children. Health Aff. 2019, 38, 765–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gundersen, C.; Kreider, B.; Pepper, J.J. The Economics of Food Insecurity in the United States. Appl. Econ. Perspect. Policy 2011, 33, 281–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gundersen, C.; Ziliak, J.P. Food Insecurity and Health Outcomes. Health Aff. 2015, 34, 1830–1839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Nguyen, B.T.; Ford, C.N.; Yaroch, A.L.; Shuval, K.; Drope, J. Food Security and Weight Status in Children: Interactions with Food Assistance Programs. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2017, 52, S138–S144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jensen, H.H. Food Insecurity and the Food Stamp Program. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2002, 84, 1215–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribar, D.C.; Hamrick, K.S. Dynamics of Poverty and Food Sufficiency; Food and Nutrition Research Report No. 36; Economic Research Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture: Washington, DC, USA, 2003.

- Wilde, P.; Nord, M. The Effect of Food Stamps on Food Security: A Panel Data Approach. Rev. Agric. Econ. 2005, 27, 425–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gundersen, G.; Oliveira, V. The Food Stamp Program and Food Insufficiency. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2001, 83, 875–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Huffman, S.K.; Jensen, H.H. Food Assistance Programs and Outcomes in the Context of Welfare Reform. Soc. Sci. Q. 2008, 89, 96–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bartfeld, J.; Dunifon, R. State-level Predictors of Food Insecurity among Households with Children. J. Policy Anal. Manag. 2006, 25, 921–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borjas, G.J. Food Insecurity and Public Assistance. J. Public Econ. 2004, 88, 1421–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- DePolt, R.A.; Moffitt, R.A.; Ribar, D.C. Food Stamps, Temporary Assistance for Needy Families and Food Hardships in Three American Cities. Pac. Econ. Rev. 2009, 14, 445–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mykerezi, E.; Mills, B. The Impact of Food Stamp Program Participation on Household Food Insecurity. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2010, 92, 1379–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nord, M.; Golla, A.M. Does SNAP Decrease Food Insecurity? Untangling the Self-Selection Effect; Economic Research Report No. 85; Economic Research Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture: Washington, DC, USA, 2009.

- Yen, S.T.; Andrews, M.; Chen, Z.; Eastwood, D. Food Stamp Program Participation and Food Insecurity: An Instrumental Variable Approach. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2008, 90, 117–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Yen, S.T. Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program and Food Insecurity among Families with Children. J. Policy Modeling 2017, 39, 52–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, H.H.; Kreider, B.; Zhylyevskyy, O. Investigating Treatment Effects of Participating Jointly in SNAP and WIC when the Treatment is Validated only for SNAP. South. Econ. J. 2019, 86, 124–155. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, K.M.; Moffitt, R.A. The Effect of SNAP and School Food Programs on Food Security, Diet Quality, and Food Spending: Sensitivity to Program Reporting Error. South. Econ. J. 2019, 86, 156–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman-Jensen, A.; Rabbitt, M.P.; Gregory, C.; Singh, A. Household Food Security in the United States in 2014; Economic Research Report No. 194; Economic Research Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture: Washington DC, USA, 2015.

- Ratcliffe, C.; McKernan, S.M. How Much Does SNAP Reduce Food Insecurity? The Urban Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Swann, C.A. Household History, SNAP Participation, and Food Insecurity. Food Policy 2017, 73, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J. Two Essays on the Application of Ordered Probability Model. Master’s Thesis, University of Tennessee, Knoxville, TN, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hamersma, S.; Kim, M. Food Security and Teenage Labor Supply. Appl. Econ. Perspect. Policy 2016, 38, 73–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mabli, J.; Worthington, J. Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program Participation and Child Food Security. Pediatrics 2014, 133, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Nord, M. Effects of the Decline in the Real Value of SNAP Benefits from 2009 to 2011; Economic Research Report No. 151; Economic Research Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture: Washington, DC, USA, 2013.

- Nord, M.; Prell, M. Food Security Improved Following the 2009 ARRA Increase in SNAP Benefits; Economic Research Report No. 116; Economic Research Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture: Washington, DC, USA, 2011.

- Gregory, C.A.; Smith, T.A. Salience, Food Security, and SNAP Receipt. J. Policy Anal. Manag. 2019, 38, 124–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gundersen, C.; Waxman, E.; Crumbaugh, A.S. An Examination of the Adequacy of Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) Benefit Levels: Impacts on Food Insecurity. Agric. Resour. Econ. Rev. 2019, 48, 433–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Katare, B.; Kim, J. Effects of the 2013 SNAP Benefit Cut on Food Security. Appl. Econ. Perspect. Policy 2017, 39, 662–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gundersen, C.; Kreider, B.; Pepper, J.J. Reconstructing SNAP to More Effectively Alleviate Food Insecurity in the U.S. RSF Russell Sage Found. J. Soc. Sci. 2018, 4, 113–130. [Google Scholar]

- de Cuba, S.E.; Bovell-Ammon, A.R.; Cook, J.T.; Coleman, S.M.; Black, M.M.; Chilton, M.M.; Casey, P.H.; Cutts, D.B.; Heeren, T.C.; Sandel, M.T.; et al. SNAP, Young Children’s Health, and Family Food Security and Healthcare Access. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2019, 57, 525–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaefer, H.L.; Gutierrez, I.A. The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program and Material Hardships among Low-Income Households with Children. Soc. Serv. Rev. 2013, 87, 753–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, B.; Huang, J.; Porterfield, S.L. Transition to Adulthood: Dynamics of Disability, Food Security, and SNAP Participation. J. Adolesc. 2019, 73, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chojnacki, G.J.; Gothro, A.G.; Gleason, P.M.; Forrestal, S.G. A Randomized Controlled Trial Measuring Effects of Extra Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) Benefits on Child Food Security in Low-Income Families in Rural Kentucky. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2020, 121, S9–S21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hudak, K.M.; Racine, E.F.; Schulkind, L. An Increase in SNAP Benefits Did Not Impact Food Security or Diet Quality in Youth. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2021, 121, 507–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keith-Jennings, B.; Rosenbaum, D. SNAP Benefit Boost in 2009 Recovery Act Provided Economic Stimulus and Reduced Hardship. Center on Budget and Policy Priorities; Center on Budget and Policy Priorities: Washington DC, USA, 2015; Available online: https://www.cbpp.org/research/food-assistance/snap-benefit-boost-in-2009-recovery-act-provided-economic-stimulus-and (accessed on 27 February 2021).

- United States Census Bureau. Current Population Survey (CPS); United States Census Bureau, U.S. Department of Commerce: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. Available online: https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/cps.html (accessed on 27 February 2021).

- U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service (USDA-ERS). Food Security in the United States. 2021. Available online: https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/food-nutrition-assistance/food-security-in-the-us/ (accessed on 27 February 2021).

- Coleman-Jensen, A.; McFall, W.; Nord, M. Food Insecurity in Households with Children–Prevalence, Severity, and Household Characteristics, 2010–2011; Economic Research Report No. 113; Economic Research Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture: Washington DC, USA, 2013.

- Coleman-Jensen, A.; Rabbitt, M.P.; Gregory, C.; Singh, A. Household Food Security in the United States in 2019; Economic Research Report No. 275; Economic Research Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture: Washington DC, USA, 2020.

- Gregory, C.A.; Coleman-Jensen, A. Do High Food Prices Increase Food Insecurity in the United States? Appl. Econ. Perspect. Policy 2013, 35, 679–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mabli, J.; Ferrerosa, C. Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program Caseload Trends and Changes in Measures of Unemployment, Labor Underutilization, and Program Policy from 2002 to 2008; Mathematica Policy Research Inc.: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Gregory, C.; Ploeg, M.V.; Andrews, M.; Coleman-Jensen, A. Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) Participation Leads to Modest Changes in Diet Quality; Economic Research Report No. 147; Economic Research Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture: Washington, DC, USA, 2013.

| Variable | Definitions | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Endogenous variables | |||

| FI | Household food insecurity category: 0 = food secure (FS), 1 = food | 0.69 | 0.87 |

| insecure among adults only (FIA); 2 = low food security among children (LFSC); 3 = very low food security among children (VLFSC) | |||

| SNAP | Any member(s) in household received SNAP benefits past 12 months | 0.58 | 0.49 |

| Continuous explanatory variables | |||

| Age | Age of respondent | 33.41 | 8.06 |

| Work hours | Respondent’s work hours per week | 18.21 | 19.58 |

| Income | Household annual income in $10,000 | 1.67 | 0.97 |

| Household size | Number of persons living in household | 4.24 | 1.56 |

| Children | Number of children < 18 years of age | 2.25 | 1.16 |

| Binary explanatory variables (yes = 1, no = 0) | |||

| State policy variables | |||

| BBCE | State uses broad-based categorical eligibility (BBCE) categorical eligibility for SNAP | 0.55 | |

| Simplified reporting | State uses simplified reporting for households with earnings | 0.88 | |

| Vehicle test | State excludes at least one, but not all, vehicles in household from SNAP asset test | 0.12 | |

| Household characteristics | |||

| Year 2009 | Data collected in 2009 | 0.28 | |

| Year 2010 | Data collected in 2010 | 0.32 | |

| Year 2011 | Data collected in 2011 (reference) | 0.40 | |

| HW household | Primary husband-wife household | 0.45 | |

| MSA | Resides in metropolitan statistical area | 0.77 | |

| South | (Reference person) resides in south | 0.35 | |

| Northeast | Resides in northwest | 0.14 | |

| West | Resides in west (reference) | 0.27 | |

| Midwest | Resides in midwest | 0.24 | |

| More money | Need to spend more money to buy enough food to meet needs | 0.34 | |

| Respondent/reference person characteristics | |||

| Male | Gender is male | 0.31 | |

| Married | Married | 0.47 | |

| Not married | Not married (reference) | 0.33 | |

| Separated | Separated or divorced | 0.20 | |

| <High school | <High school education | 0.28 | |

| High school | High school graduate (reference) | 0.36 | |

| Some college | Attended college but no degree | 0.21 | |

| College | Has college education or higher | 0.15 | |

| Employed | Employed | 0.55 | |

| Unemployed | Unemployed | 0.16 | |

| Not in labor force | Not in labor force (reference) | 0.30 | |

| Hispanic | Of Hispanic origin | 0.30 | |

| White | White | 0.72 | |

| Black | Black (reference) | 0.20 | |

| Other race | Other race | 0.08 | |

| Sample size | 5677 | ||

| Food Insecure Category | ATE |

|---|---|

| Food-insecure among adults (FIA) | −0.073 (0.008) |

| Low food security among children (LFSC) | 0.052 (0.006) |

| Very low food security among children (VLFSC) | 0.021 (0.003) |

| Variable | Probability |

|---|---|

| Continuous explanatory variables | |

| Age/10 | −6.76 (0.82) *** |

| Work hours/10 | −4.57 (0.57) *** |

| Income | −11.29 (0.67) *** |

| Household size | 3.51 (0.63) *** |

| Children | 2.30 (0.73) *** |

| Binary explanatory variables | |

| Year 2009 | −5.22 (1.55) *** |

| Year 2010 | −1.18 (1.45) |

| Male | 0.92 (1.49) |

| HW household | −15.16 (4.31) *** |

| <High school | 0.17 (1.59) |

| Some college | −0.74 (1.65) |

| College | −7.05 (1.85) *** |

| Employed | 5.22 (2.25) ** |

| Unemployed | 4.24 (1.96) ** |

| Hispanic | −9.32 (1.56) *** |

| White | −2.23 (1.77) |

| Other race | −0.28 (2.63) |

| MSA | −3.30 (1.45) ** |

| South | −0.04 (1.76) |

| Northeast | 2.97 (2.15) |

| Midwest | 3.11 (1.85) * |

| Married | 0.33 (4.09) |

| Separated | 0.05 (1.84) |

| More money | 6.69 (1.26) *** |

| BBCE | 6.37 (1.34) *** |

| Simplified reporting | 7.28 (2.08) *** |

| Vehicle test | 2.14 (1.78) |

| Conditional on SNAP Participation | Conditional on SNAP Nonparticipation | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | FS | FIA | LFSC | VLFSC | FS | FIA | LFSC | VLFSC |

| Continuous explanatory variables | ||||||||

| Age/10 | −2.77 (0.76) *** | 0.91 (0.26) *** | 1.56 (0.43) *** | 0.30 (0.08) *** | −2.78 (0.80) *** | 0.60 (0.17) *** | 1.70 (0.50) *** | 0.48 (0.15) *** |

| Income | 1.61 (0.67) ** | −0.57 (0.22) ** | −0.89 (0.38) ** | −0.16 (0.07) ** | 1.96 (0.70) *** | −0.35 (0.15) ** | −1.22 (0.43) *** | −0.38 (0.13) *** |

| Children | −1.59 (0.69) ** | 0.54 (0.23) ** | 0.89 (0.39) ** | 0.17 (0.07) ** | −1.74 (0.73) ** | 0.35 (0.15) ** | 1.07 (0.45) ** | 0.32 (0.13) ** |

| Binary explanatory variables | ||||||||

| Year 2009 | −3.20 (1.38) ** | 1.03 (0.45) ** | 1.81 (0.79) ** | 0.35 (0.16) ** | −3.27 (1.45) ** | 0.67 (0.28) ** | 2.01 (0.90) ** | 0.59 (0.28) ** |

| Male | 3.18 (1.41) ** | −1.08 (0.49) ** | −1.77 (0.78) ** | −0.33 (0.14) ** | 3.36 (1.50) ** | −0.72 (0.33) ** | −2.06 (0.92) ** | −0.58 (0.26) ** |

| College | 5.18 (1.66) *** | −1.85 (0.62) *** | −2.84 (0.90) *** | −0.49 (0.15) *** | 5.67 (1.81) *** | −1.28 (0.46) *** | −3.45 (1.09) *** | −0.95 (0.28) *** |

| Unemployed | −5.27 (1.71) *** | 1.67 (0.51) *** | 3.00 (0.99) *** | 0.60 (0.22) *** | −5.61 (1.75) *** | 1.00 (0.28) *** | 3.50 (1.11) *** | 1.11 (0.38) *** |

| White | −3.03 (1.52) ** | 1.02 (0.53) * | 1.69 (0.84) ** | 0.31 (0.16) ** | −3.17 (1.63) * | 0.68 (0.36) * | 1.93 (0.99) * | 0.55 (0.29) * |

| Other race | −7.22 (2.40) *** | 2.17 (0.65) *** | 4.16 (1.42) *** | 0.88 (0.35) ** | −7.47 (2.43) *** | 1.24 (0.32) *** | 4.68 (1.54) *** | 1.55 (0.59) *** |

| MSA | −2.96 (1.35) ** | 1.01 (0.48) ** | 1.65 (0.75) ** | 0.30 (0.13) ** | −3.07 (1.45) ** | 0.67 (0.33) ** | 1.87 (0.88) ** | 0.52 (0.24) ** |

| Midwest | 3.10 (1.67) * | −1.06 (0.59) * | −1.73 (0.92) * | −0.32 (0.16) * | 3.22 (1.79) * | −0.71 (0.40) * | −1.97 (1.09) * | −0.55 (0.30) * |

| More money | −34.72 (1.22) *** | 10.48 (0.53) *** | 20.76 (0.91) *** | 3.48 (0.37) *** | −35.28 (1.17) *** | 4.85 (0.45) *** | 23.80 (0.94) *** | 6.63 (0.55) *** |

| BBCE | 3.12 (1.05) *** | −1.02 (0.35) *** | −1.76 (0.59) *** | −0.34 (0.12) *** | 3.17 (1.11) *** | −0.67 (0.22) *** | −1.94 (0.68) *** | −0.56 (0.21) *** |

| Simplified reporting | 3.55 (1.38) ** | −1.11 (0.42) *** | −2.02 (0.79) ** | −0.41 (0.17) ** | 3.61 (1.43) ** | −0.71 (0.25) *** | −2.23 (0.89) ** | −0.67 (0.29) ** |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, J.; Wang, Y.; Yen, S.T. Does Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program Reduce Food Insecurity among Households with Children? Evidence from the Current Population Survey. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3178. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18063178

Zhang J, Wang Y, Yen ST. Does Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program Reduce Food Insecurity among Households with Children? Evidence from the Current Population Survey. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(6):3178. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18063178

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Jun, Yanghao Wang, and Steven T. Yen. 2021. "Does Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program Reduce Food Insecurity among Households with Children? Evidence from the Current Population Survey" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 6: 3178. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18063178