An Economic Analysis of Brownfield and Greenfield Industrial Parks Investment Projects: A Case Study of Eastern Slovakia

Abstract

:1. Introduction

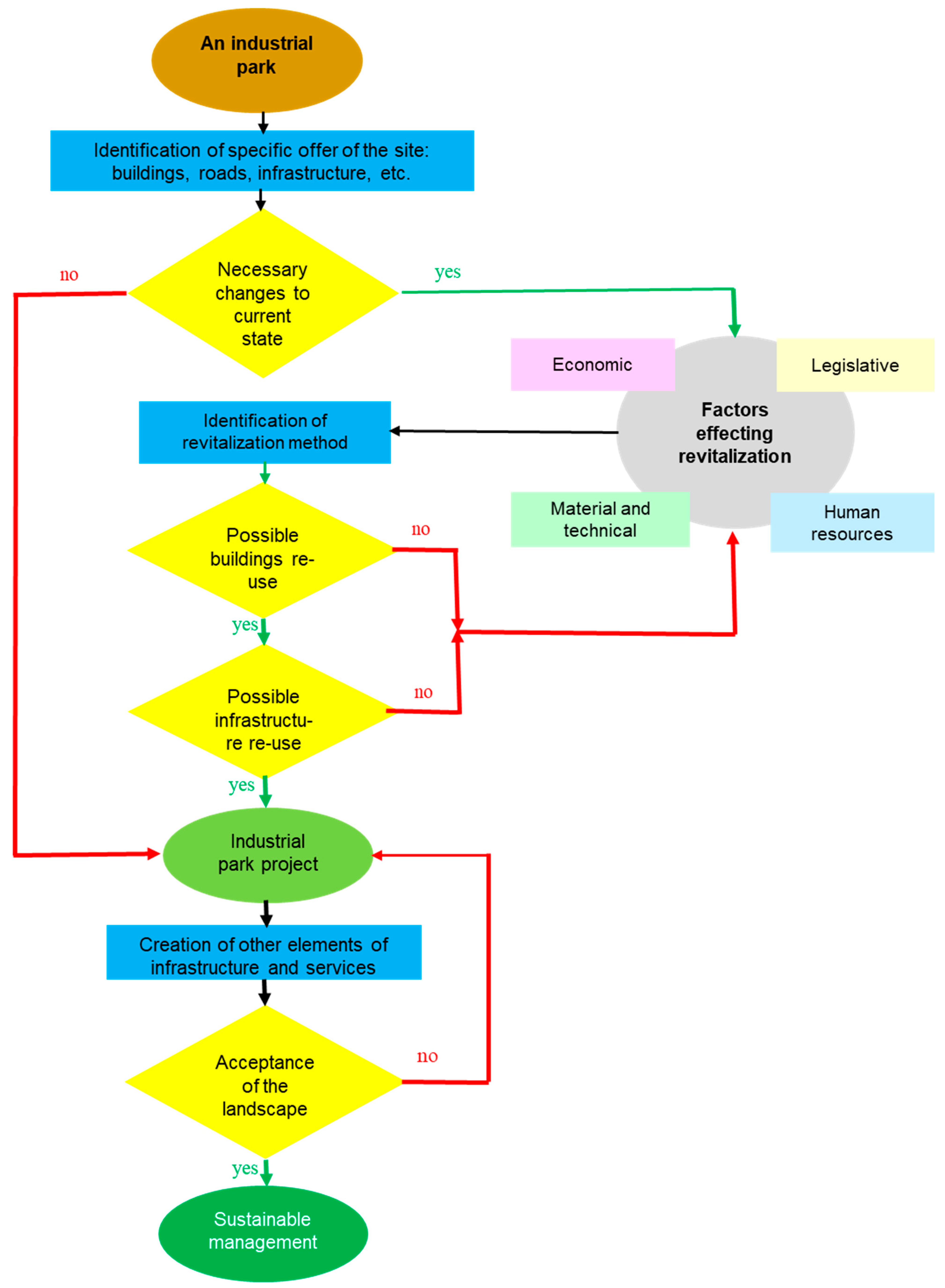

2. Background

- Shows how individual buildings and open spaces will be linked.

- Defines the height, overall geometry, and size of buildings, describes proposed relations between buildings and public spaces.

- Determines the distribution of the provided activities or use.

- Identifies the system of movement of people—walking, cycling, car or public transport, service, and vehicles for waste disposal.

- Establishes the basis for the provision of other infrastructure elements and public services.

- Combines the physical form with the socio-economic and cultural context and the interests of all concerned.

- Allows understanding how well an industrial park is integrated with the surrounding context of the landscape and the natural environment.

3. Objects of Study and Methods

- Um(x)—overall usefulness of the evaluated project (stability index), m = 1, 2, 3, …, m,

- αi—the weight of the i-th criterion defined by the decision-making body; Σαi = 1,

- ui(xi)—the usefulness of the i-th criterion for xi, where often ui(xi) = xi,

- xi—the value of the result according to the i-th criterion.

4. Results

4.1. Analysis

- Existing transport and technical infrastructure.

- Existing manufacturing and other objects.

- Good connection to the regional and global freight transport system.

- Good connection to a functioning public transport system.

- Contact with existing subcontractors and services.

- Sufficient workforce in residential areas in the vicinity or within public transport.

- Investor density.

- Job density.

- Non-repayable financial contribution (NFC) per job.

- Occupancy of the industrial park.

- A: Industrial parks achieving above-average results.

- B: Industrial parks achieving average results.

- C: Industrial parks achieving sub-average results.

4.2. Results of the Analysis

- Arranging the development of business in industry, reducing registered unemployment, and improving the life quality of the population.

- Implementation of interactions between public administration, investors, entrepreneurs, and subcontractors, which determine the competitiveness of the industry in the region.

- Reclamation and modernization of former industrial facilities after mining activities for the sustainability of investments.

5. Discussion

- The price of the land is lower in the case of brownfield.

- The cost of land preparation and construction is significantly higher in the case of brownfield.

- The time necessary to prepare land for construction is significantly longer in the case of brownfield.

- The cost of building comparable types of objects is the same, i.e., the type of land in this case is insignificant.

- Brownfields are mainly located in the inner parts of towns and cities, where the rental as well as the cost of real estate are generally substantially lower, and the vacancy rate of the properties is higher when rented.

- The operating costs for brownfields are higher because they are increased by the costs of monitoring the environmental status of the site and additional costs of protecting the building compared to normal costs.

- Governance.

- Infrastructure.

- Territorial issues.

- Finance.

- Culture.

- Environment.

6. Conclusions

- The total cost of new construction.

- The cost of land preparation.

- The time needed for preparation of the land.

- The costs of environmental counselling.

- The developer costs.

- The investor’s own capital requirement.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pavolová, H.; Csikósová, A.; Bakalár, T. Brownfields as a tool for support of regional development of Slovakia. Appl. Mech. Mater. 2012, 209–211, 1679–1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacko, R.; Hajduová, Z. Determinants of environmental efficiency of the EU countries using two-step DEA approach. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bednárová, L.; Džuková, J.; Grosoš, R.; Gomory, M.; Petráš, M. Legislative instruments and their use in the management of raw materials in the Slovak Republic. Acta Montan. Slovaca 2020, 25, 105–115. [Google Scholar]

- Limasset, E.; Pizzol, L.; Merly, C.; Gatchett, A.M.; Le Guern, C.; Martinát, S.; Klusáček, P.; Bartke, S. Points of attention in designing tools for regional brownfield prioritization. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 622–623, 997–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Knapčíková, L.; Rimár, M.; Fedák, M. New Trends in Waste Management in the Selected Region of the Slovak Republic. In Proceedings of the MMS Conference, Starý Smokovec, Slovakia, 22–24 November 2017; EAI: Gent, Belgium, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, F.; Geertman, S.; Kuffer, M.; Zhan, Q. An integrative methodology to improve brownfield redevelopment planning in Chinese cities: A case study of Futian, Shenzhen. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2011, 35, 388–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khouri, S.; Pavolová, H.; Cehlár, M.; Bakalár, T. Metallurgical brownfields re-use in the conditions of Slovakia—A case study. Metalurgija 2016, 55, 500–502. [Google Scholar]

- Bakalár, T.; Puškárová, P.; Pavol, M.; Jurkasová, Z. Comparative model of brownfields and greenfields usage for support of regional development. In Proceedings of the 16th International Multidisciplinary Scientific GeoConference-SGEM, Albena, Bulgaria, 28 June–6 July 2016; STEF92 Technology Ltd.: Sofia, Bulgaria, 2016; pp. 163–169. [Google Scholar]

- Peric, A. Brownfield redevelopment versus Greenfield investment—Case study Ecka industrial zone in Zrenjanin, Serbia. Tech. Technol. Educ. Manag. 2011, 6, 541–551. [Google Scholar]

- Stojkov, B. Oživljavanje braunfilda. In Oživljavanje Braunfilda u Srbiji, 1st ed.; Danilović, K., Stojkov, B., Zeković, S., Gligorijević, Ž., Damjanović, D., Eds.; PALGO Centar: Beograd, Serbia, 2008; pp. 53–60. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, N.; Zhu, Y.; Ibrahim, M.; Waqas, M.; Waheed, A. Development of a Standard Brownfield Definition, Guidelines, and Evaluation Index System for Brownfield Redevelopment in Developing Countries: The Case of Pakistan. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ahmad, N.; Zhu, Y.; Hongli, L.; Karamat, J.; Waqas, M.; Mumtaz, S.M.T. Mapping the obstacles to brownfield redevelopment adoption in developing economies: Pakistani Perspective. Land Use Policy 2020, 91, 104374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, S.; Jain, M.; Tripathi, V. Greenfield Investments: An Economic and Financial Key Driver for India’s Growth. Manag. Econ. Res. J. 2019, 5, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregorová, B.; Hronček, P.; Tometzová, D.; Molokáč, M.; Čech, V. Transforming Brownfields as Tourism Destinations and Their Sustainability on the Example of Slovakia. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osman, R.; Frantál, B.; Klusáček, P.; Kunc, J.; Martinát, S. Factors affecting brownfield regeneration inpost-socialist space: The case of the Czech Republic. Land Use Policy 2015, 48, 309–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enell, A.; Andersson-Sköld, Y.; Vestin, J.; Wagelmans, M. Risk management and regeneration of brownfields using bioenergy crops. J. Soils Sediments 2016, 16, 987–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardos, R.P.; Jones, S.; Stephenson, I.; Menger, P.; Beumer, V.; Neonato, F.; Maring, L.; Ferber, U.; Track, T.; Wendler, K. Optimising value from the soft re-use of brownfield sites. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 563–564, 769–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lorber, L. Holistic approach to revitalised old industrial areas. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 120, 326–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pavolová, H.; Bakalár, T.; Emhemed, E.M.A.; Hajduová, Z.; Pafčo, M. Model of sustainable regional development with implementation of brownfield areas. Entrep. Sustain. Issues 2019, 6, 1088–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Loo, B.P.Y.; Cheng, A.H.T.; Nichols, S.L. Transit-oriented development on greenfield versus infill sites: Some lessons from Hong Kong. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2017, 167, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartke, S.; Schwarze, R. No perfect tools: Trade-offs of sustainability principles and user requirements in designing support tools for land-use decisions between greenfields and brownfields. J. Environ. Manag. 2015, 153, 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maantay, J.A.; Maroko, A.R. Brownfields to Greenfields: Environmental Justice versus Environmental Gentrification. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Anguelovski, I. From toxic sites to parks as (green) LULUs? Newchallenges of inequity, privilege, gentrification, and exclusion for urban environmental justice. J. Plan. Lit. 2016, 31, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Kirkwood, N.; Maksimović, Č.; Zhen, X.; O’Connor, D.; Jin, Y.; Hou, D. Nature based solutions for contaminated land remediation and brownfield redevelopment in cities: A review. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 663, 568–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, B.H. The application of industrial ecology principles and planning guidelines for the development of eco-industrial parks: An Australian case study. J. Clean. Prod. 2004, 12, 997–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherwood, M.W.; Pollard, J. Responsible Investing: An Introduction to Environmental, Social, and Governance Investments, 1st ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Lupu, D. Cost-benefit Analysis for Transport Infrastructure Projects: Eastern European Cases. J. Public Adm. Financ. Law 2019, 15, 107–123. [Google Scholar]

- Frantál, B.; Kunc, J.; Nováková, E.; Klusáček, P.; Martinát, S.; Osman, R. Location Matters! Exploring Brownfields Regeneration in a Spatial Context (A Case Study of the South Moravian Region, Czech Republic). Morav. Geogr. Rep. 2013, 21, 5–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, A.; de Sousa, J.F.; Costa, J.P.; Neves, B. Mapping stakeholder perception on the challenges of brownfield sites’ redevelopment in waterfronts: The Tagus Estuary. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2020, 28, 2447–2464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sosnovskikh, S. Peculiarities in the development of special economic zones and industrial parks in Russia. Eur. J. Geogr. 2017, 8, 82–102. [Google Scholar]

- Cappai, F.; Forgues, D.; Glaus, M. A Methodological Approach for Evaluating Brownfield Redevelopment Projects. Urban Sci. 2019, 3, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Majumdar, M.; Sen, J. Spatial Pattern of Brownfield-Greenfield development across Urban-Rural Transition: A case study of Kolkata Metropolitan Area. Int. J. Eng. Res. Appl. 2020, 10, 33–38. [Google Scholar]

- Marian-Potra, A.; Işfănescu-Ivan, R.; Pavel, S.; Ancuţa, C. Temporary Uses of Urban Brownfields for Creative Activities in a Post-Socialist City. Case Study: Timişoara (Romania). Sustainability 2020, 12, 8095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajduová, Z.; Andrejovský, P.; Beslerová, S. Development of quality of life economic indicators with regard to the environment. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 110, 747–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chowdhury, S.; Kain, J.-H.; Adelfio, M.; Volchko, Y.; Norrman, J. Greening the Browns: A Bio-Based Land Use Framework for Analysing the Potential of Urban Brownfields in an Urban Circular Economy. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bařinka, K. Indikátory a metoda kategorizace brownfields problematiky v obcích. In Proceedings of the Obce a Brownfields, Brno, Czech Republic, 29 November 2005; DHV ČR s.r.o.: Praha, Czech Republic, 2005; pp. 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Ferber, U.; Grimski, D.; Millar, K.; Nathanail, P. Sustainable Brownfield Regeneration: CABERNET Network Report, 1st ed.; University of Nottingham: Nottingham, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Pavolová, H.; Cehlár, M.; Soušek, R. Vplyv Antropogénnej Činnosti na Kvalitu Životného Prostredia, 1st ed.; Institut Jana Pernera: Pardubice, Czech Republic, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Krczmářová, E. Brownfieldy jako investiční příležitost nejen pro průmysl—Nástroje řešení. In Proceedings of the Obce a Brownfields, Brno, Czech Republic, 29 November 2005; DHV ČR s.r.o.: Praha, Czech Republic, 2005; pp. 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Pavolová, H.; Pavol, M.; Bakalár, T. SAW method application in selection of roads construction suppliers. Actual Probl. Econ. 2017, 189, 348–356. [Google Scholar]

- Harsanyi, J.C. Cardinal welfare, individualistic ethics, and interpersonal comparisons of utility. J. Political Econ. 1955, 63, 309–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Churchman, C.W.; Ackoff, R.J.; Amoff, E.L. Introduction to Operation Research, 1st ed.; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, C.L.; Yoon, K. Multiple Attribute Decision Making—Method and Applications, A State-of-the-Art Survey, 1st ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, Y.H.; Yeh, C.H. Evaluating airline competitiveness using multiattribute decision making. Omega 2001, 29, 405–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virvou, M.; Kabassi, K. Evaluating an intelligent graphical user interface by comparison with human experts. Knowl. Based Syst. 2004, 17, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T. Comparative analysis of SAW and TOPSIS based on interval-valued fuzzy sets: Discussions on score functions and weight constraints. Expert Syst. Appl. 2012, 39, 1848–1861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacCrimmon, K.R. Decision Making among Multiple Attribute Alternatives: A Survey and Consolidated Approach, 1st ed.; The RAND Corporation: Santa Monica, CA, USA, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.J.; Hwang, C.L. Fuzzy Multiple Attribute Decision Making: Methods and Applications, 1st ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Einhorn, H.J.; McCoach, W. A simple multiattribute utility procedure for evaluation. Behav. Sci. 1977, 22, 270–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, S.; Chang, Y.; Shen, C. A fuzzy simple additive weighting system under group decision-making for facility location selection with objective/subjective attributes. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2008, 189, 132–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y. A fuzzy multi-criteria decision-making model based on simple additive weighting method and relative preference relation. Appl. Soft Comput. 2015, 30, 412–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakouri, G.H.; Nabaee, M.; Aliakbarisani, S. A quantitative discussion on the assessment of power supply technologies: DEA (data envelopment analysis) and SAW (simple additive weighting) as complementary methods for the “Grammar”. Energy 2014, 64, 640–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saffarian, S.; Zaredar, N. Risk Assessment of Human Activities on Protected Areas: A Case Study. Hum. Ecol. Risk Assess. 2015, 21, 1462–1478. [Google Scholar]

- Griffith, A.; Headley, J.D. Using a weighted score model as an aid to selecting procurement methods for small building Works. Constr. Manag. Econ. 1997, 15, 341–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei, A.; Shayestehfar, M.; Hassani, H.; Mohammadi, M. Assessment of the metals contamination and their grading by SAW method: A case study in Sarcheshmeh copper complex, Kerman, Iran. Environ. Earth Sci. 2015, 74, 3191–3205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hosseini, S.; Oladi, J.; Amirnejad, H. The evaluation of environmental, economic and social services of national parks. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naghdi, F.; Monavvari, S.M.; Hosseini, S.M.; Gharagozlu, A. Industrial zoning using multicriteria evaluation modeling. Appl. Ecol. Environ. Res. 2017, 15, 1565–1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazher, K.M.; Chan, A.P.C.; Zahoor, H.; Ameyaw, E.E.; Edwards, D.J.; Osei-Kyei, R. Modelling capability-based risk allocation in PPPs using fuzzy integral approach. Can. J. Civ. Eng. 2019, 46, 777–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maier, K.; Čtyroký, J. Ekonomika Územního Rozvoje, 1st ed.; Grada Publishing: Prague, Czech Republic, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Ferber, U.; Nathanail, P.; Bergatt Jackson, J.; Górski, M.; Krzywon, R.; Drobiec, L.; Petríková, D.; Finka, M. Brownfields Handbook, 1st ed.; VŠB-TUO: Ostrava, Czech Republic, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- De Sousa, C.A. Measuring the public costs and benefits of brownfield versus greenfield development in the Greater Toronto area. Environ. Plan. B Plan. Des. 2002, 29, 251–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayali, A.S. Is FDI beneficial for development in any case: An empirical comparison between greenfield and brownfield invetments. Doğuş Üniv. Derg. 2014, 15, 15–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- SIEA: Priemyselné Parky Podporené v Rámci Sektorového Operačného Programu Priemysel a Služby. Available online: https://www.siea.sk/priemyselne-parky-podporene-v-ramci-sektoroveho-operacneho-programu-priemysel-a-sluzby/ (accessed on 28 December 2020).

- Cehlár, M.; Janočko, J.; Šimková, Z.; Pavlík, T.; Tyulenev, M.; Zhironkin, S.; Gasanov, M. Mine Sited after Mine Activity: The Brownfields Methodology and Kuzbass Coal Mining Case. Resources 2019, 8, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Theisen, G.; Gertler, E.; Ahmed, R.; Kountz, S.; Neill, L. Brownfield/Greenfield Development Cost Comparison Study, 1st ed.; Group Mackenzie: Portland, OR, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Morio, M.; Schädler, S.; Finkel, M. Applying a multi-criteria genetic algorithm framework for brownfield reuse optimization: Improving redevelopment options based on stakeholder preferences. J. Environ. Manag. 2013, 130, 331–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahzouni, A. Urban brownfield redevelopment and energy transition pathways: A review of planning policies and practices in Freiburg. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 195, 1476–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, N.; Zhu, Y.; Shafait, Z.; Sahibzada, U.F.; Waheed, A. Critical barriers to brownfield redevelopment in developing countries: The case of Pakistan. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 212, 1193–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Brownfields | Economic Description |

|---|---|

| Suitably located | The market will “take care” of them. Possible public non-monetary intervention can increase the benefits for the local community. |

| Less suitably located | Public intervention and, where appropriate, the involvement of public funds, which are the cost gap of the project, is necessary. The usual ratio of public and private investment is from 1:5 or more in this case. |

| Non-commercial locations | Require more social goals or environmental protection. The share of public funds is higher than the private funds, usually 1:4. |

| Critical state | Dangerous, health- or environment-threatening. If it is no longer possible to find and bring the originator of pollution to the responsibility, the removal of damages is paid out of public funds. |

| Factor | f1 | f2 | f3 | f4 | f5 | f6 | f7 | f8 | f9 | f10 | f11 | Σ | αi |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| f1 | 0 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1 | 2.0 | 0.05 |

| f2 | 0.5 | 0 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1 | 7.5 | 0.19 |

| f3 | 0.5 | 0 | 0 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1 | 4.5 | 0.11 |

| f4 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1 | 7.0 | 0.17 |

| f5 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0 | 0 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.5 | 3.5 | 0.09 |

| f6 | 0 | 0 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1.5 | 0.04 |

| f7 | 0.5 | 0 | 0.5 | 0 | 0.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.5 | 0 | 0.5 | 1.5 | 0.04 |

| f8 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.5 | 3.5 | 0.09 |

| f9 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0 | 1 | 0.5 | 3.0 | 0.07 |

| f10 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3.0 | 0.07 |

| f11 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0 | 0 | 3.5 | 0.09 |

| Sum | 40.5 | 1.00 | |||||||||||

| Factor | αi | Brownfield | Greenfield | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Points | Σ | Points | Σ | ||

| existing transport infrastructure | 0.05 | 4 | 0.198 | 1 | 0.05 |

| existing technical infrastructure | 0.19 | 4 | 0.741 | 1 | 0.19 |

| existing manufacturing and other objects | 0.11 | 4 | 0.444 | 1 | 0.11 |

| purchase price of the land | 0.17 | 2 | 0.346 | 4 | 0.69 |

| quality connection to the regional and global freight transport system | 0.09 | 4 | 0.346 | 2 | 0.17 |

| the cost of landscaping | 0.04 | 1 | 0.037 | 4 | 0.15 |

| contact with existing subcontractors and services | 0.04 | 3 | 0.111 | 2 | 0.07 |

| environmental burden | 0.09 | 1 | 0.086 | 4 | 0.35 |

| additional costs of the investment project | 0.07 | 1 | 0.074 | 4 | 0.3 |

| operating costs | 0.07 | 2 | 0.148 | 2 | 0.15 |

| time of the plot preparation | 0.09 | 2 | 0.173 | 4 | 0.35 |

| Sum | 2.70 | 2.57 | |||

| Location of Industrial Park | Region | Type of Industrial Park |

| Poprad | Prešov | greenfield |

| Snina | Prešov | brownfield |

| Lipany | Prešov | greenfield |

| Vranov nad Topľou | Prešov | greenfield |

| Prešov | Prešov | greenfield |

| Jaklovce | Košice | brownfield |

| Kojšov | Košice | brownfield |

| Trebišov | Košice | brownfield |

| Hnúšťa | Banská Bystrica | brownfield |

| Detva | Banská Bystrica | brownfield |

| Lučenec | Banská Bystrica | greenfield |

| Vígľaš | Banská Bystrica | greenfield |

| Myjava | Trenčín | greenfield |

| Galanta | Trnava | greenfield |

| Hurbanovo | Nitra | greenfield |

| Diakovce | Nitra | greenfield |

| Factor | Brownfield | Greenfield |

| Land use data | ||

| Land area (m2) | 80,000 | 80,000 |

| Built-up area (m2) | 28,322 | 0 |

| Building coefficient (built-up area/land area) | 0.35 | 0 |

| The current number of landowners | 2 | 2 |

| Data on land development costs | ||

| Land price (€) | 719,976 | 1,188,342 |

| Price of the land preparation for construction | ||

| Removing environmental issues (€) | 597,491 | 0 |

| Other land preparation costs (€) | 3,314,745 | 2,980,745 |

| Construction costs | ||

| Cost of construction (€) | 196,176 | 196,176 |

| Other costs (€) | 5885 | 1962 |

| Soft cost | ||

| Legal (€) | 73,027 | 29,211 |

| Others—planning, designing (€) | 98,918 | 98,918 |

| Environmental consulting (€) | 179,247 | 4481 |

| Building loan cost (€) | 560,977 | 272,190 |

| Subtotal (€) | 5,746,442 | 5,106,025 |

| Developer expenses 5% (€) | 172,393 | 152,185 |

| Total cost (€) | 5,918,835 | 5,258,210 |

| Total cost per m2 of new construction (€) | 209 | 184 |

| Operating cash flow | ||

| Number of tenants | 3 | 3 |

| Market rent (€) | 1,057,748 | 1,224,656 |

| Vacancy rate—market vacancy (%) | 10 | 7 |

| Object guard costs (€) | 136,586 | 68,293 |

| Costs to monitor the state of the environment (€) | 73,027 | 0 |

| Net operating income (€) | 848,105 | 1,156,363 |

| Financing and investing | ||

| Loan amount (€) | 5,642,131 | 5,274,514 |

| Cash flow before tax (€) | 8133 | 20,331 |

| Net capital requirement (€) | 282,107 | 214,080 |

| Return on investment (%) | 2.9 | 9.5 |

| Length of territory preparation for construction (months) | 18 | 6 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pavolová, H.; Bakalár, T.; Tokarčík, A.; Kozáková, Ľ.; Pastyrčák, T. An Economic Analysis of Brownfield and Greenfield Industrial Parks Investment Projects: A Case Study of Eastern Slovakia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3472. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18073472

Pavolová H, Bakalár T, Tokarčík A, Kozáková Ľ, Pastyrčák T. An Economic Analysis of Brownfield and Greenfield Industrial Parks Investment Projects: A Case Study of Eastern Slovakia. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(7):3472. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18073472

Chicago/Turabian StylePavolová, Henrieta, Tomáš Bakalár, Alexander Tokarčík, Ľubica Kozáková, and Tomáš Pastyrčák. 2021. "An Economic Analysis of Brownfield and Greenfield Industrial Parks Investment Projects: A Case Study of Eastern Slovakia" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 7: 3472. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18073472

APA StylePavolová, H., Bakalár, T., Tokarčík, A., Kozáková, Ľ., & Pastyrčák, T. (2021). An Economic Analysis of Brownfield and Greenfield Industrial Parks Investment Projects: A Case Study of Eastern Slovakia. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(7), 3472. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18073472