1. Introduction

China has the largest population of smokers in the world, but has one of the lowest smoking cessation rates [

1]. Data from the Global Adult Tobacco Survey (GATS), 2010, reveal that China was the second lowest among all GATS countries in terms of quit rates, measured by the proportion of former smokers among ever smokers [

1]. The more recent GATS 2018 data in China showed that 16.1% of Chinese smokers planned or were thinking about quitting in the next 12 months, a figure unchanged from 2010 [

2]. Behavioural theories, such as theory of planned behaviour [

3], and transtheoretical model of behaviour change [

4], consider behavioural intention as an important component in behaviour change. The primary goal of this study is to identify factors that could be targeted by policymakers to improve smokers’ intentions to quit.

A growing body of literature is looking at the factors that are associated with smokers’ intentions to quit. Previous studies have found that sociodemographic variables, including age, educational attainment, and family income, are associated with intentions to quit [

5]. Smoking-related factors, such as knowledge about smoking-related diseases [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10], home smoking rules [

11], nicotine dependence, and previous quit attempts also predict smokers’ quit intentions. In addition, smoking rationalisation beliefs, also known as self-exempting beliefs, which justify or rationalise their smoking behaviours can also predict a lack of intention to quit [

5]. Our paper is related to [

12], a study conducted in 2010. Using a population-based sample from the International Tobacco Control (ITC) China Wave 1 survey, reference [

12] examines the variations between current, former, and never smokers’ health knowledge about smoking. They also studied the impact of health knowledge on smokers’ intentions to quit. Recent work on this, however, is lacking. Our study aims to compare people’s perceptions and attitudes on health hazards of smoking over time by using more recent data sources, which include questions that follow the standard design in GATS. In addition, we extend our understanding on smokers’ intentions to quit by including two factors that were not considered in previous studies: advice from doctors and self-perceived health. We aim to identify the relative importance of health knowledge about smoking and doctors’ advice to quit smoking in motivating smokers to quit. This question is relevant to policymakers in allocating resources, as the former would require the resources be directed to educate smokers, but the latter suggests a more effective use of resources to train health care providers.

4. Discussion

Our study shows among 2509 current smokers (aged 15–69) surveyed in Ningbo, a city located in the Yangtze River Delta in South China; the proportion who intended to quit at any point in the future was about 38% in 2018–2019. We examined the association of intention to quit with a smoker’s health knowledge about smoking, doctors’ advice to quit, and self-perceived health, controlling for demographic and socioeconomic factors.

We observed a significantly lower level of health knowledge about smoking among current smokers compared to the former smokers and those who never smoked. This finding is consistent with [

12], using the Wave 1 (2006) ITC China survey with a sample of 1000 adults in six cities in China. Similar to the GATS 2018 China results [

2], we found that the majority (90%) of adults are aware that smoking causes lung cancer, but fewer (51–54%) are aware that smoking also causes stroke or heart diseases. These figures represent significant improvement compared to that in 2010. In the GATS 2010 China results, about 78% of adults agreed that smoking caused lung cancer and only 27% (39%) agreed that smoking caused stroke (heart attack) [

1]. Levels of health knowledge among Chinese smokers, notwithstanding, were considerably lower than levels previously reported in western countries. For example, in Canada, which has some of the most progressive tobacco control policies in the world, approximately 83% of smokers agreed that smoking causes stroke and 91% agreed that smoking causes heart disease, in 2002 [

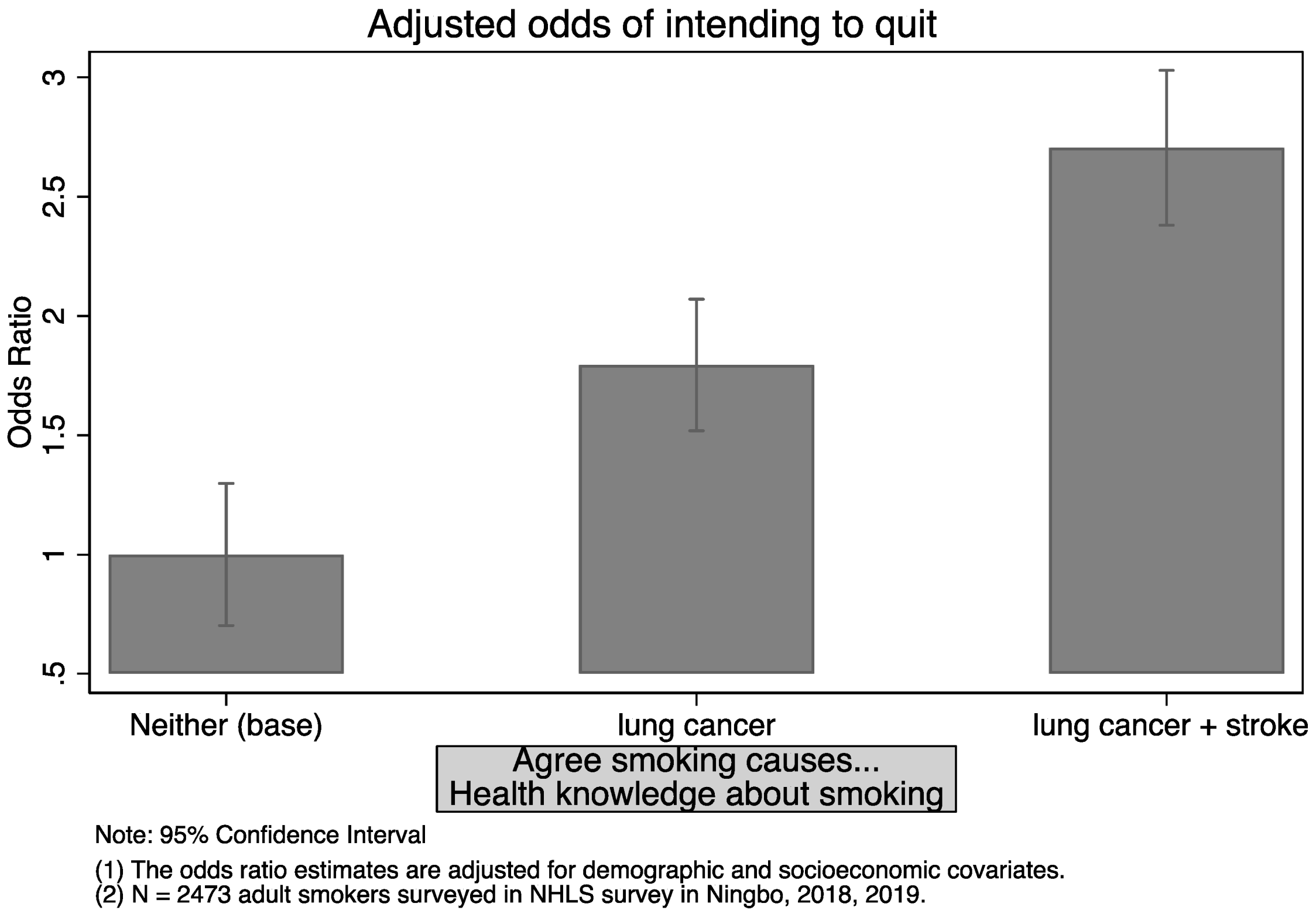

18]. The corresponding figures in our sample of smokers are 52% and 47%. We examined the extent to which this knowledge gap has implications on smokers’ intentions to quit. We found that the effect of knowing smoking causes lung cancer and stroke, relative to no such knowledge, potentially doubles the odds of intending to quit, outweighing the effect of knowing smoking causes lung cancer only. We contrast this finding by plotting the associated odds ratio in

Figure A1 in

Appendix B.

We extended previous studies by examining the relative importance of health knowledge and doctors’ advice in affecting the cessation behaviour of smokers in

Table 6. We found that health knowledge is associated with a smoker’s intention to quit, but is not associated with their past attempts of quitting or whether a smoker quit in the time window of 12 months. In contrast, not only is doctors’ advice associated with a current smoker’s intention to quit, but it is also associated with a smoker’s action to quit. Our findings are consistent with the transtheoretical model of health behaviour change. According to [

18], to progress from pre-contemplation (i.e., do not want to quit) to contemplation (i.e., intended to quit), the pros of changing must increase. To progress from contemplation to action, the cons of changing must decrease. Health knowledge potentially motivates a smoker to transition from precontemplation stage to contemplation stage, but plays a limited role in motivating smokers into action. In contrast, doctors’ advice to quit might play a more important role in helping the smokers to progress to the action stage. We illustrate in a schematic (

Figure A2 in

Appendix B) how health knowledge and advice from doctors potentially influence a smoker’s decision to quit at different stages. This is also evidenced in a recent study that finds cessation advice from health care professionals helps those in the contemplation and preparation stage [

19].

The important role of doctors’ advice to quit might be an outcome of better knowledge about the health risks of smoking. To address this concern, we test whether the effect of doctors’ advice depends on smoker’s health knowledge, by including interaction terms. The interaction term is not significantly different from one (these results are not reported by available upon request). In other words, doctors’ advice to quit is associated with a smoker’s intention to quit regardless of their health knowledge about smoking.

We also observe a relationship between self-reported health status and smokers’ intentions to quit. Those who self-reported good health are less likely to consider quitting. This might arise for two reasons. Firstly, smokers’ belief about the health risks of smoking influences their decision to quit. This is in line with [

12,

20,

21], where smokers who reported greater worry about the future health effects of smoking and smokers who reported health benefits from quitting are likely to consider quitting. On the other hand, self-reported health status is a good measure of the general health status of an adult. The second reason, therefore, is that worse physical health motivates smokers to quit. To test the extent to which the two explanations hold, we add number of chronic diseases in our model to control for the physical health of smokers as an objective health indicator. These results are presented in Panel A,

Table A2 in the

Appendix A.

Self-reported health status remains significant in columns (1)–(2) in

Table A2 in the

Appendix A, indicating smokers are indeed influenced by their beliefs (about their own health), and this effect cannot be explained by their more objective health statuses. In column (3) in

Table A2 in the

Appendix A, when the outcome of quitting instead of intention or attempt is considered, self-reported good health is no longer significant but the estimate on number of chronic diseases is highly significant. This is reasonable given “to have quit” for a period of time would often require more external assistance than beliefs alone. To identify which disease types are more likely to “trigger” a smoker to quit, we replaced the number of chronic diseases with five dummy variables, indicating specific types of diseases (see Panel B in

Table A2 in the

Appendix A). The likelihood of quitting increased when smokers were diagnosed with cerebrovascular diseases or cancer. For example, it shows if a smoker was diagnosed with cerebrovascular disease, the odds of quitting in the past 12 months increase by 277%.

The above findings highlight the importance of disease prevention and control. Smoking doubles the risk of having a heart attack and it causes 84% of deaths from lung cancer and 83% of deaths from chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) [

22]. This knowledge was more relevant when a smoker had the diagnosis with a disease instead of being informed of the risk of developing the illness. Thus, the quitting attempts are more likely to be triggered by health care providers than by a smoker’s own knowledge about the harm of smoking. Our view is in line with “although awareness and acceptance of the health risks of smoking may not be a sufficient condition for quitting, it is likely a necessary one for most smokers and serves an important source of motivation” [

23].

It is worth nothing that our finding does not imply medical doctors hold a central role in motivating smokers to quit. In countries where quitting programs have been successful, substantial socio-environmental changes were made along with tobacco control policies and televised antismoking advertising [

24,

25]. Our finding suggests advice from health care providers is likely to supplement these campaigns. A similar study to ours, using data of Korean adult smokers, found that a doctors’ advice to quit alone increases the likelihood of a smoker’s intention to quit within 1 month (OR = 2.14,

p < 0.05), but not within 6 months or someday in the future. However, it is likely to increase the effect of a significant other’s advice [

26]. In other words, smokers who had been advised to quit smoking by both significant others and medical professionals are more likely to consider quitting than those who had been advised to quit by significant others only.

There are several limitations in our study, and our findings should be interpreted with caution. Firstly, this is a cross-sectional study. There might exist factors that influence a smoker’s intention to quit and the likelihood of getting advice from doctors to quit smoking. It is likely that people living in communities with better access to health facilities are more likely to be advised by doctors to quit smoking. They are also more likely to consider quitting in the future, because there is a higher level of trust among residents in the same communities. Previous studies found that being a smoker was associated with a higher level of perceived income inequality, lower perception of relative material well-being, and living in a community with a lower degree of trust and safety [

27]. Information of community characteristics of smokers’ residence is likely to correct this problem, and we consider it a direction for future research. Secondly, our data are not representative nationally, and Ningbo represents one of the cities with better economic development in China. We do not think our findings apply to all regions in China. Lastly, in order to demonstrate that smokers are triggered to quit based on misbelieves of their health statuses, we included chronic diseases as objective measures of health. They can still be argued to be subjective because some illnesses might not be diagnosed.