Response Inhibition, Cognitive Flexibility and Working Memory in Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder, Generalized Anxiety Disorder and Social Anxiety Disorder

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

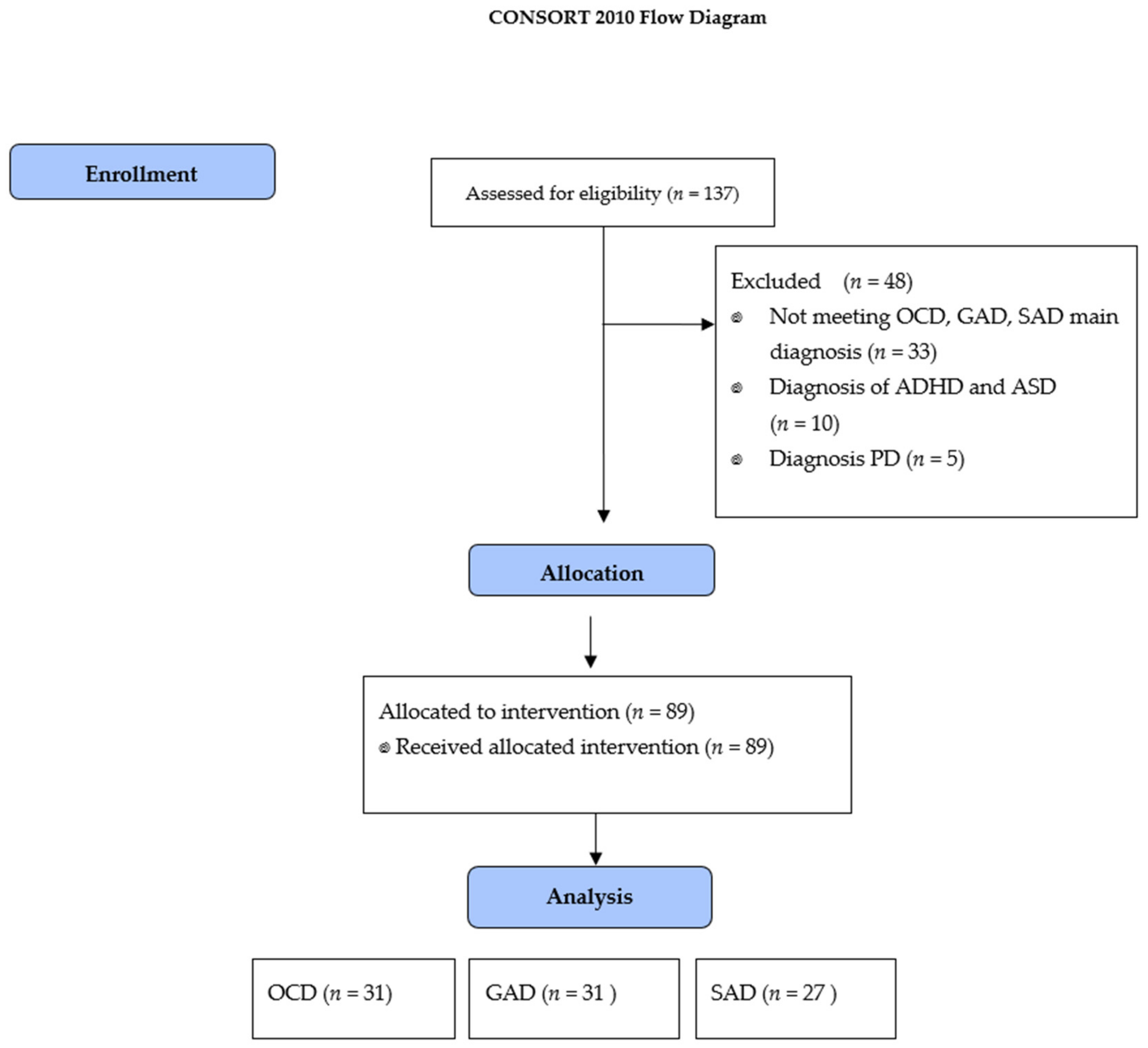

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedure

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Clinical Measures

- Yale Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale (Y-BOCS) [33]. Comprises 10 items assessing severity of OCD. It contains two subscales, obsessions (range = 0–20) and compulsions (range = 0–20) and a total score (range = 0–40). The scale has high internal consistency (α = 0.87–90) and good convergent validity (r = 0.74 to r = 0.47). A total average greater than or equal to 16 is considered of clinical significance. In this study, Cronbach’s alpha in the OCD group was 0.86.

- Penn State Worry Questionnaire (PSWQ) [34]. A 16-item self-report scale that assesses the general tendency to worry, especially present in generalized anxiety disorder. The cut-off point for detection of generalized anxiety disorder is 56. It is shown to have good psychometric properties, correlation with other measures of anxiety being satisfactory, for example, the SAI-R, with a correlation of 0.76. Cronbach’s alpha was high in the GAD group (α = 0.96).

- Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale (LSAS) [35]. A 24-item scale that measures fear and avoidance of social situations over the past week. It consists of 11 items relating to social interaction and 13 items related to public performance. Each item is rated on two 4-point Likert-type scales by a clinician who may ask questions to clarify the appropriate rating for a specific participant. A total average greater than or equal to 51 is considered of clinical significance. Cronbach’s alpha in the SAD group was 0.91.

- Beck-II Depression Inventory (BDI) [36]. A 21-item self-report scale that measures depression severity. Classification of scores was as follows: minimal (0 to 13), mild (14 to 19), moderate (20 to 28) and severe (>29). The internal consistency coefficient ranged between 0.87 and 0.89. Cronbach’s alpha in all participants was 0.91.

- Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) [37]. A 21-item self-report scale that measures degree of anxiety. Classification of scores was as follows: minimal (0 to 7), mild (8 to 15), moderate (16 to 25) and severe (26+). The internal consistency coefficients varied between 0.85 and 0.93. Cronbach’s alpha in all participants was 0.92.

2.3.2. Neuropsychological Measures

- Wisconsin card sorting test (WCST) [38]. Assesses CF or attentional change using a set of cards. The most important measures are: number of categories completed, perseverative responses, total errors, perseverative errors and non-perseverative errors. The T-score is used taking age and educational level into account. The psychometric properties of the WCST have been widely researched, and it is a valid and reliable instrument, with oscillating reliability coefficients between 0.39 and 0.72.

- Stroop color word test (SCWT) [39]. Assesses the ability to inhibit the automatic tendency to respond verbally and, therefore, control response to conflicting stimuli (words, colors, words / colors and interference). This test is a good measure of cognitive inhibition. Test-retest reliability was 0.85, 0.81, 0.69.

- Digits span test (WAIS-IV) [42]. This test evaluates verbal WM and consists of three sub-tasks (forward, backward and increasing order). The most important measure is the maximum number of elements (Span) that the individual can remember short term in backward or increasing order. Test-retest reliability oscillated between 0.70 and 0.85.

- Corsi block task (WMS-III) [43]. Evaluates visuospatial WM and consists of a forward and backward task. The most important data is the SPAN backward. Test-retest reliability oscillated between 0.70 and 0.82.

- Reynolds intellectual screening test (RIST) [44]. It has its origin in the RIAS scales (Reynolds Intellectual Assessment Scales) comprising two subtests: guess (verbal subtest) and categories (nonverbal subtest). In this study, only categories measuring nonverbal abstract reasoning were used. As with RIAS, it maintains high test-retest reliability 0.84.

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Group Equivalence

3.2. A Comparison of Groups in CF, RI and WM

3.3. CF, RI and WM Controlling Nonverbal Reasoning

3.4. Intragroup Comparisons Based on Comorbidity and the Use of Pharmacotherapy

3.5. Correlation between EF and Obsessions, Worry and Social Anxiety

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Publishing: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Storch, E.A.; Lewin, A.B.; Farrell, L.; Aldea, M.A.; Reid, J.; Geffken, G.R.; Murphy, T.K. Does cognitive-behavioral therapy response among adults with obsessive–compulsive disorder differ as a function of certain comorbidities? J. Anxiety Disord. 2010, 24, 547–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chamberlain, S.; Blackwell, A.; Fineberg, N.; Robbins, T.; Sahakian, B. The neuropsychology of obsessive compulsive disorder: The importance of failures in cognitive and behavioural inhibition as candidate endophenotypic markers. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2005, 29, 399–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyake, A.; Friedman, N.P. The Nature and Organization of Individual Differences in Executive Functions. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2012, 21, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lehto, J.E.; Juujärvi, P.; Kooistra, L.; Pulkkinen, L. Dimensions of executive functioning: Evidence from children. Br. J. Dev. Psychol. 2003, 21, 59–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shields, G.S.; Sazma, M.A.; Yonelinas, A.P. The effects of acute stress on core executive functions: A meta-analysis and comparison with cortisol. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2016, 68, 651–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Carlson, S.M.; Wang, T.S. Inhibitory control and emotion regulation in preschool children. Cogn. Dev. 2007, 22, 489–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, P.; Le Bastard, G.; Pochon, J.; Levy, R.; Allilaire, J.; Dubois, B.; Fossati, P. Executive functions and updating of the contents of working memory in unipolar depression. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2004, 38, 567–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chevalier, N.; Blaye, A. Cognitive flexibility in preschoolers: The role of representation activation and maintenance. Dev. Sci. 2008, 11, 339–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zebdi, R.; Goyet, L.; Pinabiaux, C.; Guellaï, B. Psychological Disorders and Ecological Factors Affect the Development of Executive Functions: Some Perspectives. Front. Psychiatry 2016, 7, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- O’Toole, M.S.; Pedersen, A.D. A systematic review of neuropsychological performance in social anxiety disorder. Nord. J. Psychiatry 2011, 65, 147–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, L.J.; Hollander, E.; Decaria, C.M.; Stein, D.J.; Simeon, D.; Liebowitz, M.R.; Aronowitz, B.R. Specificity of neuropsychological impairment in obsessive-compulsive disorder: A comparison with social phobic and normal control subjects. J. Neuropsychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 1996, 8, 82–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graver, C.J.; White, P.M. Neuropsychological effects of stress on social phobia with and without comorbid depression. Behav. Res. Ther. 2007, 45, 1193–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachs, G.; Anderer, P.; Doby, D.; Saletu, B.; Dantendorfer, K. Impaired conditional discrimination learning in social phobia. Neuropsychobiology 2003, 47, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujii, Y.; Kitagawa, N.; Shimizu, Y.; Mitsui, N.; Toyomaki, A.; Hashimoto, N.; Kako, Y.; Tanaka, T.; Asakura, S.; Koyama, T.; et al. Severity of generalized social anxiety disorder correlates with low executive functioning. Neurosci. Lett. 2013, 543, 42–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frick, A.; Howner, K.; Fischer, H.; Eskildsen, S.F.; Kristiansson, M.; Furmark, T. Cortical thickness alterations in social anxiety disorder. Neurosci. Lett. 2013, 536, 52–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, S.L.; Heinrichs, N.; Kim, H.J.; Hofmann, S.G. Liebowitz social anxiety scale as a self-report instrument: A preliminary psychometric analysis. Behav. Res. Ther. 2002, 40, 701–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heeren, A.; Maurage, P.; Philippot, P. Revisiting attentional processing of non-emotional cues in social anxiety: A specific impairment for the orienting network of attention. Psychiatry Res. 2015, 228, 136–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, H.T.; Gómez-Ariza, C.J.; Garcia-Lopez, L.-J. Stopping the past from intruding the present: Social anxiety disorder and proactive interference. Psychiatry Res. 2016, 238, 284–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demetriou, E.A.; Song, C.Y.; Park, S.H.; Pepper, K.L.; Naismith, S.L.; Hermens, D.F.; Hickie, I.B.; Thomas, E.E.; Norton, A.; White, D.; et al. Autism, Early Psychosis, and Social Anxiety Disorder: A transdiagnostic examination of executive function cognitive circuitry and contribution to disability. Transl. Psychiatry 2018, 8, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Dang, C.; Maes, J.H. Effects of working memory training on EEG, cognitive performance, and self-report indices potentially relevant for social anxiety. Biol. Psychol. 2020, 150, 107840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, R.R.; Partington, J.E. A Psychometric Comparison of Narcotic Addicts with Hospital Attendants. J. Gen. Psychol. 1942, 27, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.L.; Christensen, R.E.; Ruggieri, A.; Schettini, E.; Freeman, J.B.; Garcia, A.M.; Flessner, C.; Stewart, E.; Conelea, C.; Dickstein, D.P. Cognitive performance of youth with primary generalized anxiety disorder versus primary obsessive-compulsive disorder. Depress. Anxiety 2019, 36, 130–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becker, E.S.; Rinck, M.; Margraf, J.; Roth, W.T. The emotional Stroop effect in anxiety disorders. J. Anxiety Disord. 2001, 15, 147–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinck, M.; Becker, E.S.; Kellermann, J.; Roth, W.T. Selective attention in anxiety: Distraction and enhancement in visual search. Depress. Anxiety 2003, 18, 18–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuelz, A.K.; Hohagen, F.; Voderholzer, U. Neuropsychological performance in obsessive-compulsive disorder: A critical review. Biol. Psychol. 2004, 65, 185–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castaneda, A.E.; Tuulio-Henriksson, A.; Marttunen, M.; Suvisaari, J.; Lönnqvist, J. A review on cognitive impairments in depressive and anxiety disorders with a focus on young adults. J. Affect. Disord. 2008, 106, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, E.S.; Roth, W.T.; Andrich, M.; Margraf, J. Explicit memory in anxiety disorders. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 1999, 108, 153–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramovitch, A.; Abramowitz, J.S.; Mittelman, A. The neuropsychology of adult obsessive–compulsive disorder: A meta-analysis. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2013, 33, 1163–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramovitch, A.; McCormack, B.; Brunner, D.; Johnson, M.; Wofford, N. The impact of symptom severity on cognitive function in obsessive-compulsive disorder: A meta-analysis. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2019, 67, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, N.Y.; Lee, T.Y.; Kim, E.; Kwon, J.S. Cognitive functioning in obsessive-compulsive disorder: A meta-analysis. Psychol. Med. 2013, 44, 1121–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, H.R.; Miyake, A.; Hankin, B.L. Advancing understanding of executive function impairments and psychopathology: Bridging the gap between clinical and cognitive approaches. Front. Psychol. 2015, 6, 328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Goodman, W.K.; Price, L.H.; Rasmussen, S.A.; Mazure, C.; Fleischmann, R.L.; Hill, C.L.; Heninger, G.R.; Charney, D.S. The Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 1989, 46, 1006–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, T.; Miller, M.; Metzger, R.; Borkovec, T.D. Development and validation of the penn state worry questionnaire. Behav. Res. Ther. 1990, 28, 487–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heimberg, R.G.; Horner, K.J.; Juster, H.R.; Safren, S.A.; Brown, E.J.; Schneier, F.R.; Liebowitz, M.R. Psychometric properties of the Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale. Psychol. Med. 1999, 29, 199–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, A.T.; Steer, R.A.; Brown, G.K.; Sanz, J.; Valverde, C.V. Inventario de Depresión de Beck (BDI-II); Pearson: Madrid, Spain, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, A.T.; Steer, R.A. Inventario de Ansiedad de Beck (BAI); Pearson: Madrid, Spain, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Heaton, R.K.; Chelune, G.J.; Talley, J.L.; Kay, G.G.; Curtiss, G. WCST: Test de Clasificación de Tarjetas de Wisconsin; TEA: Madrid, Spain, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Golden, C.J. STROOP: Test de Colores y Palabras: Manual; TEA Ediciones S.A.: Madrid, Spain, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Brophy, M.; Taylor, E.; Hughes, C. To Go or not to Go: Inhibitory Control in ‘Hard to Manage’ Children. Infant Child Dev. 2002, 11, 125–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorell, L.B.; Bohlin, G.; Rydell, A.-M. Two types of inhibitory control: Predictive relations to social functioning. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 2004, 28, 193–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wechsler, D. WAIS-IV, Escala de Inteligencia de Wechsler para Adultos-IV. In Manual Técnico y de Interpretación; Pearson: Madrid, Spain, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler, D. WMS III, Escala de Memoria de Wechsler-III; Pearson: Madrid, Spain, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds, C.R.; Kamphaus, R.W.; Fernández, P.S.; Pinto, I.F. RIAS: Escalas de Inteligencia de Reynolds y RIST: Test de Inteligencia Breve de Reynolds; TEA: Madrid, Spain, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Teubner-Rhodes, S.; Vaden, K.I.; Dubno, J.R.; Eckert, M.A. Cognitive Persistence: Development and Validation of a Novel Measure from the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test; Elsevier Ltd.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; Volume 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansen, T.; Dittrich, W.H. Cognitive Performance in a Subclinical Obsessive-Compulsive Sample 1: Cognitive Functions. Psychiatry J. 2013, 2013, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Van Velzen, L.S.; Vriend, C.; De Wit, S.J.; Heuvel, O.A.V.D. Response inhibition and interference control in obsessive-compulsive spectrum disorders. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2014, 8, 419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bannon, S.; Gonsalvez, C.J.; Croft, R.J.; Boyce, P.M. Response inhibition deficits in obsessive–compulsive disorder. Psychiatry Res. 2002, 110, 165–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, L.; Lipszyc, J.; Dupuis, A.; Thayapararajah, S.W.; Schachar, R. Response inhibition and psychopathology: A meta-analysis of go/no-go task performance. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2014, 123, 429–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krishna, R.; Udupa, S.; George, C.M.; Kumar, K.J.; Viswanath, B.; Kandavel, T.; Venkatasubramanian, G.; Reddy, Y.J. Neuropsychological performance in OCD: A study in medication-naïve patients. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2011, 35, 1969–1976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalanthroff, E.; Henik, A.; Derakshan, N.; Usher, M. Anxiety, Emotional Distraction, and Attentional Control in the Stroop Task. Emotion 2016, 16, 293–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bohne, A.; Savage, C.R.; Deckersbach, T.; Keuthen, N.J.; Wilhelm, S. Motor inhibition in trichotillomania and obsessive–compulsive disorder. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2008, 42, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grillon, C.; Robinson, O.J.; O’Connell, K.; Davis, A.; Alvarez, G.; Pine, D.S.; Ernst, M. Clinical anxiety promotes excessive response inhibition. Psychol. Med. 2016, 47, 484–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carver, C.S.; Johnson, S.L.; Timpano, K.R. Toward a Functional View of the p Factor in Psychopathology. Clin. Psychol. Sci. 2017, 5, 880–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbruggen, F.; Logan, G.D. Response inhibition in the stop-signal paradigm. Trends. Cogn. Sci. 2008, 12, 418–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Johnson, D.R.; Gronlund, S.D. Individuals lower in working memory capacity are particularly vulnerable to anxiety’s disruptive effect on performance. Anxiety Stress Coping 2009, 22, 201–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashcraft, M.H.; Kirk, E.P. The relationships among working memory, math anxiety, and performance. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 2001, 130, 224–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maloney, E.A.; Risko, E.F.; Ansari, D.; Fugelsang, J. Mathematics anxiety affects counting but not subitizing during visual enumeration. Cognition 2010, 114, 293–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shackman, A.J.; Sarinopoulos, I.; Maxwell, J.S.; Pizzagalli, D.A.; Lavric, A.; Davidson, R.J. Anxiety selectively disrupts visuospatial working memory. Emotion 2006, 6, 40–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Moritz, S. Executive functioning in obsessive–compulsive disorder, unipolar depression, and schizophrenia. Arch. Clin. Neuropsychol. 2002, 17, 477–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salthouse, T.A. Consequences of Age-Related Cognitive Declines. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2012, 63, 201–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Moriya, J.; Sugiura, Y. Socially anxious individuals with low working memory capacity could not inhibit the goal-irrelevant information. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2013, 7, 840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Moriya, J.; Sugiura, Y. High Visual Working Memory Capacity in Trait Social Anxiety. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e034244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Moran, T.P. Anxiety and working memory capacity: A meta-analysis and narrative review. Psychol. Bull. 2016, 142, 831–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stopa, L.; Clark, D.M. Cognitive processes in social phobia. Behav. Res. Ther. 1993, 31, 255–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinzel, S.; Kaufmann, C.; Grützmann, R.; Hummel, R.; Klawohn, J.; Riesel, A.; Bey, K.; Lennertz, L.; Wagner, M.; Kathmann, N. Neural correlates of working memory deficits and associations to response inhibition in obsessive compulsive disorder. NeuroImage Clin. 2018, 17, 426–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martoni, R.M.; Salgari, G.; Galimberti, E.; Cavallini, M.C.; O’Neill, J. Effects of gender and executive function on visuospatial working memory in adult obsessive–compulsive disorder. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2015, 265, 707–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vries, F.E.; de Wit, S.J.; Cath, D.C.; van der Werf, Y.D.; van der Borden, V.; van Rossum, T.B.; van Balkom, A.J.; van der Wee, N.J.; Veltman, D.J.; Heuvel, O.A.V.D. Compensatory Frontoparietal Activity During Working Memory: An Endophenotype of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. Biol. Psychiatry 2014, 76, 878–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa-Alcázar, Á.; Olivares-Olivares, P.J.; Martínez-Esparza, I.C.; Parada-Navas, J.L.; Rosa-Alcázar, A.I.; Olivares-Rodríguez, J. Cognitive flexibility and response inhibition in patients with Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder and Generalized Anxiety Disorder. Int. J. Clin. Health Psychol. 2020, 20, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rey-Mermet, A.; Singh, K.; Gignac, G.E.; Brydges, C.R. Removal of information from working memory is not related to inhibition. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 2020. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/341190854_Removal_of_information_from_working_memory_is_not_related_to_inhibition (accessed on 15 November 2019). [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | OCD (n = 31) | GAD (n = 31) | SAD (n = 27) | F/χ2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (Mean ± SD) | 35.51 ± 11.34 | 30.65 ± 11.18 | 33.29 ± 9.81 | ns. |

| Sex n (%) | ns. | |||

| Men | 15 (48.4) | 11 (35.5) | 14 (51.9) | |

| Women | 16 (51.6) | 20 (64.5) | 13 (48.1) | |

| Years of disorder duration (Mean ± SD) | 13.89 ± 11.71 | 4.85 ± 4.07 | 9.56 (8.62) | F (1.88) = 7.41; p = 0.001 |

| Comorbidity n (%) | χ2 (2) = 19.22; p < 0.001 | |||

| No comorbidity | 15 (57.6) | 13 (48.1) | 27 (100) | |

| Comorbidity | 16 (42.4) | 18 (51.9) | 0 | |

| Marital status n (%) | ns. | |||

| Single | 15 (48.4) | 20 (64.5) | 20 (74.1) | |

| Married | 13 (41.9) | 9 (29) | 6 (22.2) | |

| Divorced | 3 (9.7) | 2 (6.5) | 1 (3.7) | |

| Educational level n (%) | ns. | |||

| Elementary | 7 (22.6) | 5 (16.1) | 3 (11.1) | |

| Secondary education | 5 (16.1) | 5 (16.1) | 4 (14.8) | |

| High school | 8 (25.8) | 8 (25.8) | 7 (25.9) | |

| University students | 11 (35.5) | 13 (42.0) | 13 (48.2) | |

| Psychiatric treatment Yes | 21 (67.7) | 14 (45.2) | 3 (11.1) | χ2 (2) = 24.13; p < 0.001 |

| No | 10 (32.3) | 17 (54.8) | 24 (88.9) | |

| Psychological treatment | ns | |||

| Yes No | 24 (77.4) 7 (22.6) | 26 (83.9) 5 (16.1) | 27 (100) 0 | |

| Type of pharmacotherapy | χ2 (6) = 32.22; p < 0.001 | |||

| None Antidepressant | 12 (38.7) 15 (48.4) | 17 (54.8) 14 (45.2) | 21 (77.8) 0 | |

| Antipsychotic Antidepressant + antipsic. | 1 (3.2) 3 (9.7) | 0 0 | 6 (22.2) 0 | |

| BAI (Mean ± SD) | 19.55 ± 10.39 | 23.42 ± 13.92 | 25.81 ± 6.87 | ns |

| BDI (Mean ± SD) | 20.13 ± 11.42 | 24.25 ± 7.17 | 23.15 ± 8.35 | ns. |

| Categories (Mean ± SD) | 44.84 ± 12.26 | 49.61 ± 6.75 | 57.82 ± 6.79 | F (2.88) = 6.87; p = 0.003 |

| Measures | Dependent Variables | Group | N | MEAN | SD | F | d Cohen * | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WCST | Number of categories completed | OCD | 31 | 4.90 | 1.47 | F (2; 79.3) = 0.31, p > 0.05 | OCD-GAD | −0.11 |

| GAD | 31 | 5.09 | 1.90 | GAD-SAD | −0.08 | |||

| SAD | 27 | 5.22 | 1.25 | OCD-SAD | −0.23 | |||

| Perseverative responses | OCD | 31 | 40.16 | 11.09 | F (2; 48.4) = 3,90, p = 0.027 | OCD-GAD | −0.80 | |

| GAD | 31 | 47.93 | 8.03 | GAD-SAD | −0.20 | |||

| SAD | 27 | 50.03 | 12.42 | OCD-SAD | −0.83 | |||

| Total errors | OCD | 31 | 39.03 | 9.11 | F (2; 49.7) = 3.90, p = 0.026 | OCD-GAD | −0.89 | |

| GAD | 31 | 46.54 | 7.65 | GAD-SAD | −0.25 | |||

| SAD | 27 | 46.81 | 13.81 | OCD-SAD | −0.68 | |||

| Perseverative errors | OCD | 31 | 39.54 | 10.53 | F (2; 40.1) = 5.00, p = 0.011 | OCD-GAD | −0.89 | |

| GAD | 31 | 47.87 | 8.13 | GAD-SAD | −0.23 | |||

| SAD | 27 | 50.44 | 13.54 | OCD-SAD | −0.91 | |||

| Non-perseverative errors | OCD | 31 | 39.87 | 8.04 | F (2; 52.8) = 5.04, p = 0.009 | OCD-GAD | −0.69 | |

| GAD | 31 | 45.29 | 7.64 | GAD-SAD | −0.34 | |||

| SAD | 27 | 48.15 | 9.30 | OCD-SAD | −0.96 | |||

| Go/No-Go | Errors omission | OCD | 31 | 1.29 | 2.39 | F (2; 35.8) = 5,05, p = 0.012 | OCD-GAD | −0.69 |

| GAD | 31 | 0.16 | 0.37 | GAD-SAD | 1.51 | |||

| SAD | 27 | 0.92 | 0.62 | OCD-SAD | −0.20 | |||

| Errors commission | OCD | 31 | 2.55 | 1.87 | F (2; 75.0) = 2.30, p > 0.05 | OCD-GAD | −0.44 | |

| GAD | 31 | 1.80 | 1.49 | GAD-SAD | 0.53 | |||

| SAD | 27 | 2.48 | 1.01 | OCD-SAD | −0.05 | |||

| Stroop | Stroop interference | OCD | 31 | 49.06 | 7.36 | F (2; 69.3) = 1.55, p > 0.05 | OCD-GAD | −0.05 |

| GAD | 31 | 49.42 | 7.55 | GAD-SAD | −0.49 | |||

| SAD | 27 | 45.70 | 7.78 | OCD-SAD | 0.44 | |||

| Digits | Span forward | OCD | 31 | 6.42 | 1.28 | F (2; 81.3) = 1.74, p > 0.05 | OCD-GAD | −0.33 |

| GAD | 31 | 6.83 | 1.18 | GAD-SAD | −0.17 | |||

| SAD | 27 | 7.03 | 1.14 | OCD-SAD | −0.50 | |||

| Span backward | OCD | 31 | 4.87 | 1.23 | F (2; 81.8) = 5.02, p = 0.009 | OCD-GAD | −0.14 | |

| GAD | 31 | 4.71 | 1.10 | GAD-SAD | −0.79 | |||

| SAD | 27 | 5.66 | 1.30 | OCD-SAD | −0.63 | |||

| Span increasing | OCD GAD SAD | 31 31 27 | 5.48 5.96 5.81 | 1.20 0.75 1.30 | F (2; 70.8) = 1.51; p > 0.05 | OCD-GAD GAD-SAD OCD-SAD | −0.48 0.16 −0.28 | |

| Total digit | OCD | 31 | 10.00 | 3.32 | F (2; 73.1) = 2.85, p > 0.05 | OCD-GAD | −0.09 | |

| GAD | 31 | 10.29 | 3.35 | GAD-SAD | −0.49 | |||

| SAD | 27 | 12.22 | 4.52 | OCD-SAD | −0.57 | |||

| Corsi | Span forward | OCD | 31 | 10.67 | 3.11 | F (2; 76.6) = 8.78, p < 0.01 | OCD-GAD | −0.01 |

| GAD | 31 | 10.70 | 2.03 | GAD-SAD | −1.13 | |||

| SAD | 27 | 13.11 | 2.24 | OCD-SAD | −0.89 | |||

| Span backward | OCD | 31 | 7.51 | 3.06 | F (2; 63.6) = 10.46, p < 0.01 | OCD-GAD | −0.28 | |

| GAD | 31 | 8.67 | 5.04 | GAD-SAD | −0.77 | |||

| SAD | 27 | 11.77 | 2.29 | OCD-SAD | −1.56 | |||

| Total | OCD | 31 | 16.13 | 3.13 | F (2; 67.3) = 6.39, p = 0.003 | OCD-GAD | −0.14 | |

| GAD | 31 | 16.77 | 5.88 | GAD-SAD | −0.65 | |||

| SAD | 27 | 20.00 | 3.60 | OCD-SAD | −1.15 | |||

| Measure | Dependent Variable | Group | N | Adjusted Mean | F |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Corsi | Total Corsi | OCD | 31 | 16.96 | F (2, 85) = 3.96, p = 0.026 |

| GAD | 31 | 15.78 | |||

| SAD | 27 | 21.22 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rosa-Alcázar, A.I.; Rosa-Alcázar, Á.; Martínez-Esparza, I.C.; Storch, E.A.; Olivares-Olivares, P.J. Response Inhibition, Cognitive Flexibility and Working Memory in Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder, Generalized Anxiety Disorder and Social Anxiety Disorder. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3642. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18073642

Rosa-Alcázar AI, Rosa-Alcázar Á, Martínez-Esparza IC, Storch EA, Olivares-Olivares PJ. Response Inhibition, Cognitive Flexibility and Working Memory in Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder, Generalized Anxiety Disorder and Social Anxiety Disorder. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(7):3642. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18073642

Chicago/Turabian StyleRosa-Alcázar, Ana Isabel, Ángel Rosa-Alcázar, Inmaculada C. Martínez-Esparza, Eric A. Storch, and Pablo J. Olivares-Olivares. 2021. "Response Inhibition, Cognitive Flexibility and Working Memory in Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder, Generalized Anxiety Disorder and Social Anxiety Disorder" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 7: 3642. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18073642

APA StyleRosa-Alcázar, A. I., Rosa-Alcázar, Á., Martínez-Esparza, I. C., Storch, E. A., & Olivares-Olivares, P. J. (2021). Response Inhibition, Cognitive Flexibility and Working Memory in Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder, Generalized Anxiety Disorder and Social Anxiety Disorder. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(7), 3642. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18073642