Translating Co-Design from Face-to-Face to Online: An Australian Primary Producer Project Conducted during COVID-19

Abstract

:1. Introduction

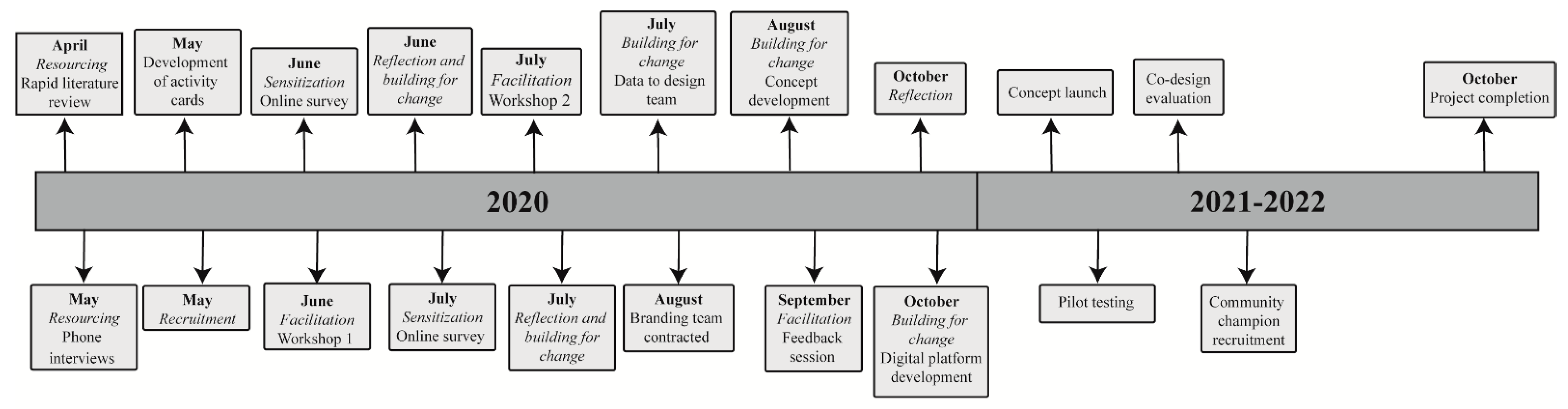

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Context

2.2. Pre-Workshop Phase

- (1)

- Resourcing (sourcing relevant information and gaining understanding of the problem to be addressed);

- (2)

- Planning (working with industry groups and other stakeholders to coordinate recruitment and workshop facilitation, planning for unforeseen challenges, e.g., COVID-19);

- (3)

- Recruiting (direct invitation of innovative and engaged primary producers and stakeholders and widening the recruitment net through a public expression of interest process);

- (4)

- Sensitizing (familiarizing participants with the context and encouraging reflection);

- (5)

- Facilitation (activities and/or discussions followed by creative development of ideas);

- (6)

- Reflecting (testing ideas for originality, feasibility, user value, transformative value of workplace systems and likelihood of preventing risks to wellbeing);

- (7)

- Building for Change (collaborative and iterative effort to build viable solutions that receive user and stakeholder support).

3. Results

3.1. Pre-Workshop Phase

3.1.1. Resourcing, Planning and Recruitment

- A call for expressions of interest made via the National Centre for Farmer Health ENews and social media platforms, the Farmer Health website www.farmerhealth.org.au (accessed on 12 July 2020), rural media outlets and digital communications channels of existing health and primary industry networks.

- Inviting Advisory Group members to nominate key individuals in their industry sector with knowledge and experience of specific workplace factors contributing to the risk of poor mental health.

3.1.2. Online Considerations for the Pre-Workshop Phase

3.2. Workshop Phase

3.2.1. Sensitizing

3.2.2. Facilitation

3.2.3. Reflection

3.2.4. Online Considerations for the Workshop Phase

3.3. Post-Workshop Phase

3.3.1. Reflection and Building for Change

3.3.2. Online Considerations for the Post-Workshop Phase

4. Discussion

- The iterative process of resourcing, planning and recruiting;

- The iterative and reflection-driven loop when online methods enable resourcing of multiple co-design workshops;

- The continuing cycle of reflection and building for change provided through (i) continuing online feedback process, industry engagement and governance and (ii) evolving and flexible design processes.

4.1. Advantages to Translating Co-Design to a Digital Environment

4.2. Challenges of Translating Co-Design to a Digital Environment

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fennell, K.M.; Jarrett, C.E.; Kettler, L.J.; Dollman, J.; Turnbull, D.A. “Watching the bank balance build up then blow away and the rain clouds do the same”: A thematic analysis of South Australian farmers’ sources of stress during drought. J. Rural. Stud. 2016, 46, 102–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazd, S.D.; Wheeler, S.A.; Zuo, A. Key Risk Factors Affecting Farmers’ Mental Health: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wheeler, S.A.; Zuo, A.; Loch, A. Water torture: Unravelling the psychological distress of irrigators in Australia. J. Rural. Stud. 2018, 62, 183–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, T.; Abernethy, K.; Brumby, S.; Hatherell, T.; Kilpatrick, S.; Munksgaard, K.; Turner, R. Sustainable Fishing Families: Developing Industry Human Capital through Health, Wellbeing, Safety and Resilience. Report to the Fisheries Research and Development Corporation. 2018. Available online: https://www.frdc.com.au/Archived-Reports/FRDC%20Projects/2016-400-DLD.pdf (accessed on 30 September 2020).

- Brumby, S.; Smith, A. ‘Train the Trainer’ Model: Implications for Health Professionals and Farm Family Health in Australia. J. Agromed. 2009, 14, 112–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ghisoni, M.; Wilson, C.A.; Morgan, K.; Edwards, B.; Simon, N.; Langley, E.; Rees, H.; Wells, A.; Tyson, P.J.; Thomas, P.; et al. Priority setting in research: User led mental health research. Res. Involv. Engag. 2017, 3, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- De’, R.; Pandey, N.; Pal, A. Impact of digital surge during Covid-19 pandemic: A viewpoint on research and practice. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2020, 55, 102171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, M.; Mills, D.; Gray, R. Expecting the unexpected? Improving rural health in the era of bushfires, novel coronavirus and climate change. Aust. J. Rural. Health 2020, 28, 107–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trischler, J.; Dietrich, T.; Rundle-Thiele, S. Co-design: From expert- to user-driven ideas in public service design. Public Manag. Rev. 2019, 21, 1595–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Value of Agricultural Commodites Produced, Australia. 2020. Available online: https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/industry/agriculture/value-agricultural-commodities-produced-australia/latest-release (accessed on 22 March 2021).

- Premier of Victoria. State of Emergency Declared in Victoria Over COVID-19. Victorian Government: Victorian Government Gazette. 2020. Available online: https://www.premier.vic.gov.au/state-emergency-declared-victoria-over-covid-19 (accessed on 4 March 2021).

- Dietrich, T.; Trischler, J.; Schuster, L.; Rundle-Thiele, S. Co-designing services with vulnerable consumers. J. Serv. Theory Pract. 2017, 27, 663–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zoom Video Communications Inc. Zoom Videoconferencing; Zoom Video Communications Inc.: San Jose, CA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Likert, R. A technique for the measurement of attitudes. Arch. Psychol. 1932, 140, 1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Palinkas, L.A.; Horwitz, S.M.; Green, C.A.; Wisdom, J.P.; Duan, N.; Hoagwood, K. Purposeful Sampling for Qualitative Data Collection and Analysis in Mixed Method Implementation Research. Adm. Policy Ment. Health Ment. Health Serv. Res. 2015, 42, 533–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Marín-Díaz, V.; Riquelme, I.; Cabero-Almenara, J. Uses of ICT Tools from the Perspective of Chilean University Teachers. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hampton, S.E.; Halpern, B.S.; Winter, M.; Balch, J.K.; Parker, J.N.; Baron, J.S.; Palmer, M.; Schildhauer, M.P.; Bishop, P.; Meagher, T.R.; et al. Best Practices for Virtual Participation in Meetings: Experiences from Synthesis Centers. Bull. Ecol. Soc. Am. 2017, 98, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cui, X.; Seignior, D. This Teaching Life: Online Learning Can Be More Interactive than Face-To-Face. Here Is Why. 2020. Available online: https://player.whooshkaa.com/episode/603257 (accessed on 10 March 2021).

- Qualtrics. Qualtrics XM (Version September 2020); Qualtrics: Provo, UT, USA, 2020; Available online: http://www.qualtrics.com (accessed on 12 October 2020).

- Hurley, E.; Trischler, J.; Dietrich, T. Exploring the application of co-design to transformative service research. J. Serv. Mark. 2018, 32, 715–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Arcury, T.A.; Gesler, W.M.; Preisser, J.S.; Sherman, J.; Spencer, J.; Perin, J. The Effects of Geography and Spatial Behavior on Health Care Utilization among the Residents of a Rural Region. Health Serv. Res. 2005, 40, 135–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nagata, J.M. Rapid Scale-Up of Telehealth during the COVID-19 Pandemic and Implications for Subspecialty Care in Rural Areas. J. Rural. Health 2021, 37, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Råheim, M.; Magnussen, L.H.; Sekse, R.J.T.; Lunde, Å.; Jacobsen, T.; Blystad, A. Researcher–researched relationship in qualitative research: Shifts in positions and researcher vulnerability. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Health Well-Being 2016, 11, 30996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sklar, J. ‘Zoom fatigue’ is taxing the brain. Here’s why that happens. National Geographic Science, 24 April 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Spicer, A. Finding endless video calls exhausting? You’re not alone. The Conversation, 6 May 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Mental Health Australia Ltd. Co-Design in Mental Health Policy. 2017. Available online: https://mhaustralia.org/publication/co-design-mental-health-policy (accessed on 30 September 2020).

- Fosslien, L.; West Duffy, M. How to combat zoom fatigue. Harvard Business Review, 29 April 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, M. Video Chat Is Helping Us Stay Employed and Connected. But What Makes It So Tiring—And How Can We Reduce ‘Zoom Fatigue’? 2020. Available online: https://www.bbc.com/worklife/article/20200421-why-zoom-video-chats-are-so-exhausting (accessed on 30 September 2020).

| Activity Card | Description |

|---|---|

| Primary Producer Success Stories | Aims to transfer knowledge and inspire positive action |

| Adapting to change | Aims to develop personal and business-related resilience skills to help overcome personal and business-related challenges |

| The resource hub | Aims to provide information and links to new and existing support resources and services to provide a one-stop-shop destination |

| On the job gym | Aims to encourage physical activity (and social connection where possible) to improve/build physical and mental strength |

| Peer mentoring network | Aims to transfer knowledge and experience and encourage personal networks |

| Your business toolkit | Aims to provide practical resources to assist with proactive business planning to ensure business success |

| Establishing your local network | Aims to support primary producers in establishing/building a local community network for the purpose of capacity building and social connection |

| Hire an expert | Aims to provide access to one-on-one expert support for primary producers |

| Recovery coach | Aims to help improve sleep and rest efficiency to increase mental, physical and business health |

| 1. | Personal connection is essential: Personal stories, local linkages and social connection are all important. |

| 2. | Keeping an eye on the goal (prevention of risks to mental health): Strategies must maintain focus on prevention of risks to mental health. |

| 3. | Language matters: Language used needs to (i) avoid stigmatization and stereotypes and (ii) reflect understandings of primary producers as goal-focused and pragmatic. |

| 4. | One size will not fit all: Strategies need to reflect the varied primary production sectors, digital connectivity, expertise, needs, age groups and geographic locations of target participants. |

| 5. | There is limited downtime as a primary producer: Primary production schedules are busy, with peak seasons of intense workload. Strategies should be achievable in manageable steps and incorporated into work routines and practices. |

| 6. | Local matters: Local experience and knowledge are often privileged. Focusing on local people, knowledge, experience and expertise will support meaningful engagement that is well timed, relatable and useful. |

| 7. | Personalization ensures engagement: Primary producers need strategies that are convenient and tailored to their needs. While unique strategies for individuals may not be possible, individuals need to feel understood and be able to identify a pathway that is right for them. |

| 8. | Virtual/digital connection is becoming more acceptable and accessible in a range of formats: Opportunities for digital engagement are becoming increasingly accepted and varied. Strategies must cross a range of mediums. |

| 9. | Utilize knowledge, resources and networks that are already in existence 1: Various local networks and resources for primary producers already exist. PPKN needs to tap into existing networks first and extend from there to those that are harder to reach. PPKN needs to act as a conduit to existing materials and resources. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kennedy, A.; Cosgrave, C.; Macdonald, J.; Gunn, K.; Dietrich, T.; Brumby, S. Translating Co-Design from Face-to-Face to Online: An Australian Primary Producer Project Conducted during COVID-19. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4147. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18084147

Kennedy A, Cosgrave C, Macdonald J, Gunn K, Dietrich T, Brumby S. Translating Co-Design from Face-to-Face to Online: An Australian Primary Producer Project Conducted during COVID-19. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(8):4147. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18084147

Chicago/Turabian StyleKennedy, Alison, Catherine Cosgrave, Joanna Macdonald, Kate Gunn, Timo Dietrich, and Susan Brumby. 2021. "Translating Co-Design from Face-to-Face to Online: An Australian Primary Producer Project Conducted during COVID-19" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 8: 4147. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18084147

APA StyleKennedy, A., Cosgrave, C., Macdonald, J., Gunn, K., Dietrich, T., & Brumby, S. (2021). Translating Co-Design from Face-to-Face to Online: An Australian Primary Producer Project Conducted during COVID-19. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(8), 4147. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18084147