In this paper we addressed five research questions focused on children’s play and independent mobility in Great Britain. This is the first paper to provide comprehensive, nationally representative data on children’s play in Britain. The findings provide important insights into where children play, how adventurously they play, and factors associated with play and independent mobility.

4.2. Research Question 2: How Adventurously Do Children Living in Britain Play? Does This Vary by Play Location?

Adventurous play has been described as beneficial for children’s fears and anxiety [

6,

7] so we addressed a second research question specifically concerning children’s adventurous play in different places. The findings indicate that children’s level of adventurous play differs across play spaces, but that this difference is relatively small, with all outdoor locations offering at least a mild level of adventure. Adventurous play was most likely to happen in green spaces, defined as trees, forests, woodland and/or grassy spaces, as well as indoor play centres, which included soft play, swimming pool and trampoline parks. This was closely followed by playgrounds and play near water. It is not surprising that the green spaces offered the highest level of adventurous play, as natural spaces by their very definition are not crafted with children’s safety in mind and they offer myriad opportunities for climbing, running, jumping and hiding. It is perhaps reassuring that children can access adventurous play and the accompanying feelings of thrill, excitement and fear, even if they do not have easy access to nature, at indoor play centres and particularly at public playgrounds, which are generally free and widely available. Concerns have been raised about whether public playgrounds offer children an appropriate level of challenge and there is evidence that some do not [

29,

30]. It is therefore vital that children’s play spaces are evaluated for the play opportunities, or affordances, that they offer, and not simply on the basis of maximising safety and minimising cost.

4.4. Research Question 4: To What Extent Are, Socio-Demographic Factors, Geographic Factors and Parental Attitudes to Risk and Protection Associated with Children’s Total Time Spent Playing, Time Spent Playing Outdoors and Time Spent Playing Adventurously?

The final two research questions focused on how geographic location, socio-demographic factors and parent/caregiver attitudes were related to children’s play and independent mobility. An important starting point for discussing these findings is to highlight that none of these predictors accounted for a large amount of variance in children’s play or independent mobility. Geographic factors explained very little variance in children’s play (<2%) but were more important for independent mobility, explaining 5% of variance. In contrast, socio-demographic factors were the strongest predictor of children’s play, accounting for around 5–7% of variance but explained less than 1% of variance in independent mobility. Parent attitudes were the strongest predictor for independent mobility, accounting for around 9% of variance in the age that children were allowed out alone. They accounted for between 3–4% of variance in play measures, being a stronger predictor of adventurous and outdoor play than total play. This is perhaps not surprising given that the measures focused on risk tolerance which we would expect to be linked to children’s risk taking during adventurous play.

Taking geographical location first, as described this predicted very little variance in children’s play. Small regional differences were found, with children in Scotland playing slightly more, particularly outside, than children in other areas of Britain and children in the East of England playing the least. Interestingly this did not lead to more adventurous play in Scotland. No systematic differences were found between children living in an urban environment, a rural environment or in a town/fringe area. Previous research has shown that features of the built environment such as traffic, increased neighbourhood greenness and access to a yard are associated with children’s outdoor play [

17]. Taken together with our findings, this suggests that it is not necessarily the type of environment a child lives in but specific features of that environment on a more local level. For example, one child might live in an urban environment but have access to a garden and low traffic areas whereas another might live in a rural environment where there is no access to a garden and where road safety is an issue.

Location was a more important predictor of independent mobility, and again it was children in Scotland who stood out, with Scottish children being allowed to be out independently at a younger age relative to all other included regions. Parents of children in the East of England reported that their child was/would be allowed out at the eldest age compared to all other regions; the average was almost two years older than the average age for children in Scotland. Children living in towns or on the fringes of urban centres were allowed out at a younger age than those living in urban and rural areas. This is consistent with previous research showing that children who live in towns make more journeys alone than children who live in rural villages or cities [

31]. Although it was not a specific focus within this paper, it seems likely that this is due to availability of infrastructure on a local level that is perceived as improving children’s safety, such as pavements and streetlights and traffic volume [

32,

33], again highlighting the importance of children’s local environment.

For socio-demographic factors, a range of these were associated with children’s play and these differed by the type of play. Children played less and played less adventurously as they got older. Across all play variables, girls played less than boys, but this difference was largest for time spent playing adventurously. Children whose participating parent was from a lower social grade spent more time playing overall, but this effect was not found for outdoor or adventurous play, indicating that these children spend more time playing, but primarily at home or in other people’s homes. In contrast, child disability was only related to hours spent playing outside and adventurously; children reported to have a diagnosed learning difficulty, a mental health problem or a physical disability spent less time playing outdoors. Perhaps surprisingly, children whose responding parent/caregiver reported that they had a health problem or disability within the past 12 months played more across all measures than children whose responding parent did not have a health problem or disability. In general, children whose responding parent/caregiver was white played more than children with a non-white parent/caregiver, but only when looking across all play locations and not for outdoor or adventurous play, and children played more if their parent/caregiver worked part-time relative to full time and if their parent/caregiver was relatively young.

To our knowledge, only one study has previously examined predictors of children’s time spent outdoors in Britain [

20]. In this study, correlations of time outdoors, rather than play specifically, were examined. Boys from a lower SES background who spent less than 2 h a day on a computer were found to spend more time outside. Our findings are only partially consistent with these; we found that children from lower SES backgrounds played more but SES was not a significant predictor of outdoor play. This inconsistency may be explained by our focus on play rather than time outdoors, our use of a nationally representative sample rather than a geographically limited opportunity sample, or the inclusion of other correlates of play within the same model that may explain some of the variance that might have been accounted for by SES. Our results are broadly consistent with previous international research. For example, Parent et al. [

18] also found that play was associated with ethnicity and a recent review highlighted consistent associations between outdoor play and maternal employment status [

19].

Socio-demographic factors were less relevant for independent mobility, with only respondent ethnicity, birth-order and respondent education level significant predictors; children whose responding caregiver was not white were older when they were allowed out, whereas children who were not first born and whose responding caregiver had completed a high level of education were younger when they were allowed out. Although the measures used and predictors examined vary, there are some similarities between our findings and previous research from the UK. For example, data from the Millennium Cohort Study also found that children had greater independent mobility if they were white [

3]. This study also found that poverty was a positive predictor of independent mobility. In our results, children of respondents in the C2DE (lower SES) category were allowed out a younger age on average, but this difference was not significant. Instead, we found that higher levels of parent/caregiver education were predictive of earlier independent mobility, which appears to contrast with the findings of Aggio and colleagues. There are, however, substantial differences between the present study and the Millennium Cohort Study with respect to the way independent mobility is assessed; our measure of independent mobility is simply the age that children are allowed out rather than any estimate of how far they are allowed to travel and/or how frequently they do so. Further, the demographic predictors examined may explain differences between these study findings, with Aggio and colleagues [

3] focusing only on child demographic factors, rather than parent/caregiver demographic factors, which we included here.

4.5. Research Question 5: To What Extent Are Socio-Demographic Factors, Geographic Factors and Parent Attitudes to Risk and Protection Associated with Children’s Independent Mobility

Parent/caregiver attitudes and beliefs about risk during play showed a small association with children’s play and a stronger association with independent mobility, although different factors were important. For play, parent/caregiver positive beliefs about risk, as measured by the engagement with risk subscale, and parent/caregiver tolerance of risk, were positively associated with the number of hours children spent playing, across all play measures. The effect was strongest for adventurous play. The protection from injury subscale was not associated with children’s time spent playing. In contrast, protection from injury was positively associated with the age that children were allowed out alone, meaning that parents who had stronger beliefs about protecting their child from injury let their children out alone at an older age. Respondents who had higher risk tolerance let their children out at a younger age. To our knowledge, this is the first study to directly examine associations between parent/caregiver attitudes to risk and children’s play and independent mobility, but the findings are in keeping with previous work showing that independent mobility was predicted by parent perceptions of safety and environment [

21]. The results provide clear evidence that parent/caregiver attitudes and beliefs around children’s risk-taking are relevant in this context, particularly in relation to adventurous play and independent mobility.

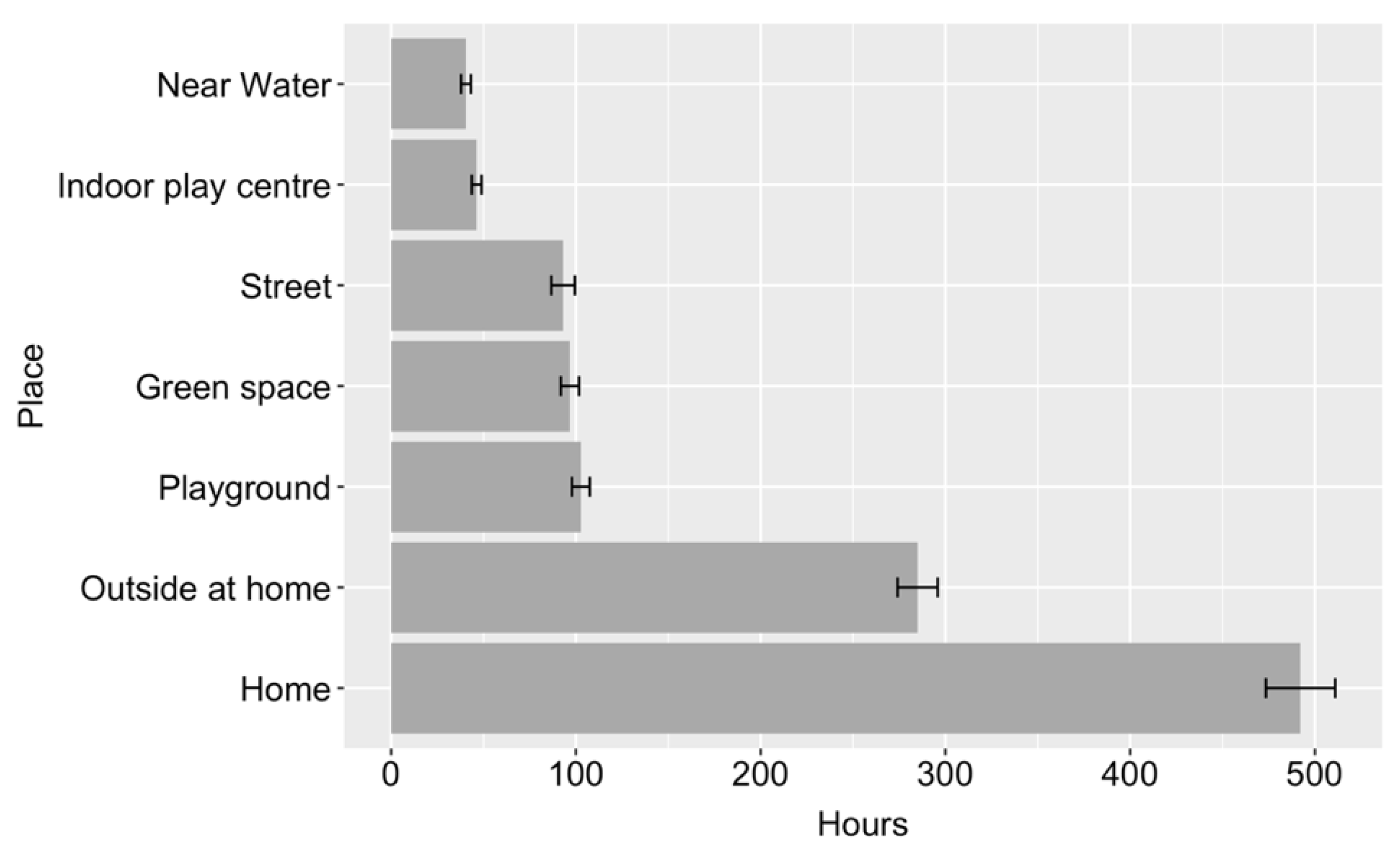

Taken together the results provide an overall picture of children’s play in 2020, before the COVID-19 pandemic. Children, on average, were playing regularly, although there is huge variation between children. This variation is explained to some degree by socio-demographic differences, geographical factors and parent attitudes and beliefs but a substantial proportion of the variation between children was not accounted for. It seems likely that this is due to factors that were not measured in the survey such as child temperament, the safety and availability of play spaces locally to the child’s home and parental attitudes and beliefs about play more broadly. A significant strength of the study is that it provides a baseline which will allow future research to examine change in children’s play, use of different play spaces and independent mobility over time.