Understanding the Differential Impact of Vegetation Measures on Modeling the Association between Vegetation and Psychotic and Non-Psychotic Disorders in Toronto, Canada

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Can the type of vegetation measure affect the significance of the association between vegetation and psychotic and non-psychotic disorders?

- What type of vegetation measures are associated with these two types of mental health disorders?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data Preparation

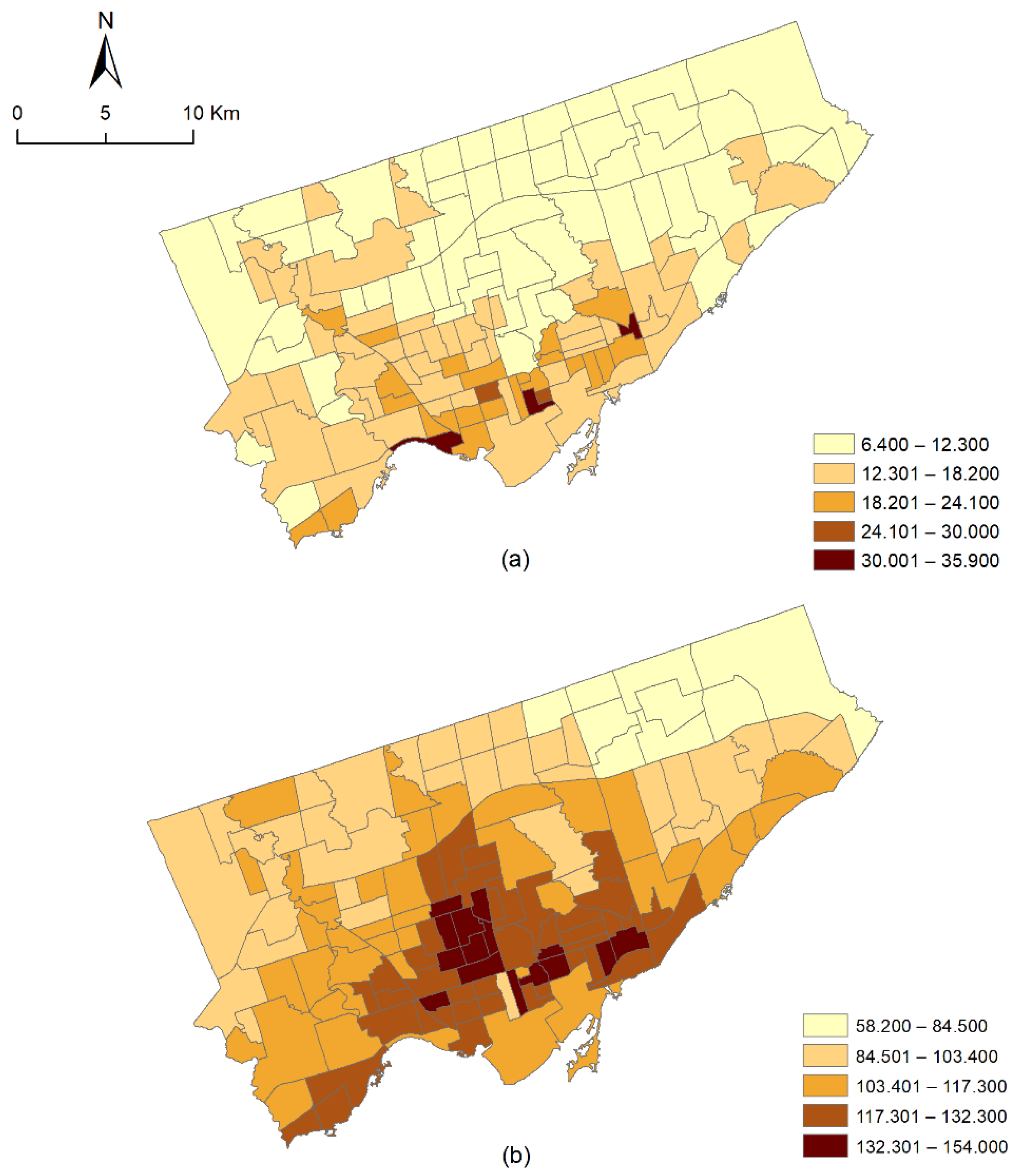

2.2.1. Mental Health Disorders

2.2.2. Landsat 8 Satellite Images

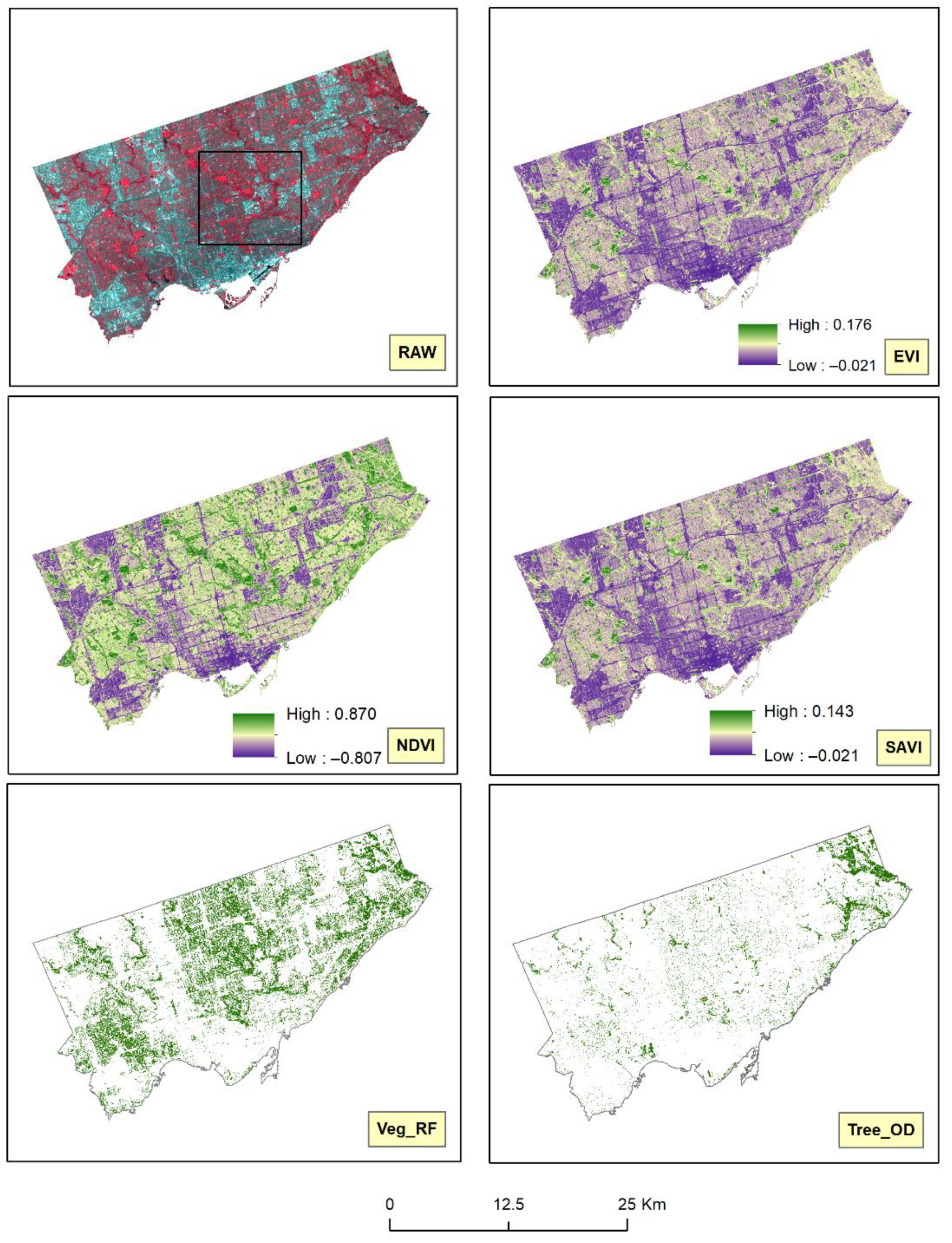

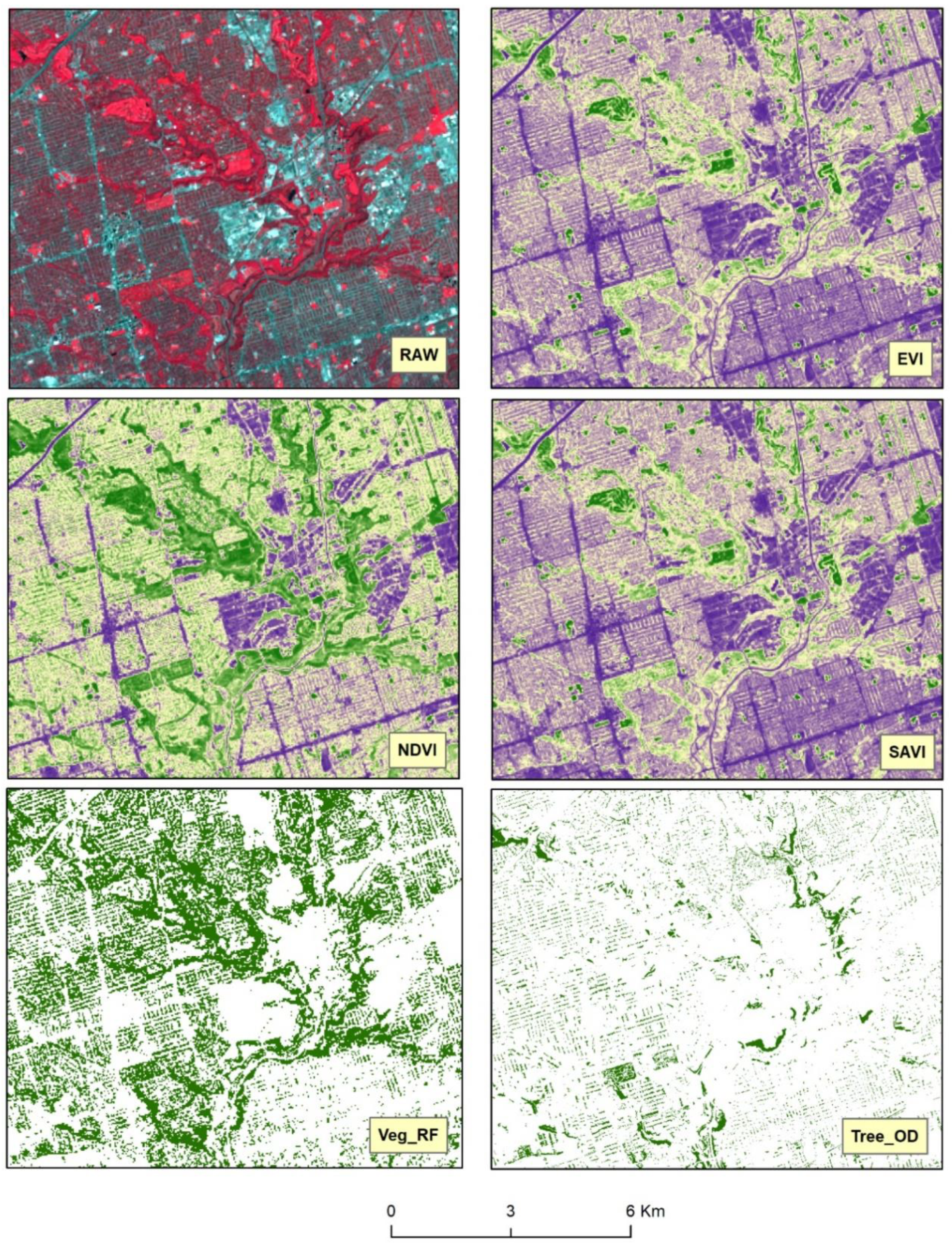

2.2.3. Construction of the Vegetation Indices

2.2.4. Developing the Land Use/Land Cover Model Using the Random Forest Ensemble

2.2.5. Processing the Tree Cover Dataset from the Open Data Portal

2.2.6. Adjusting for Potential Confounders

2.2.7. Bayesian Spatial Modeling

2.2.8. Assessment of the Relative Risk of Mental Health Disorders Due to the Variations in Vegetation Content

3. Results

3.1. Vegetation Indices

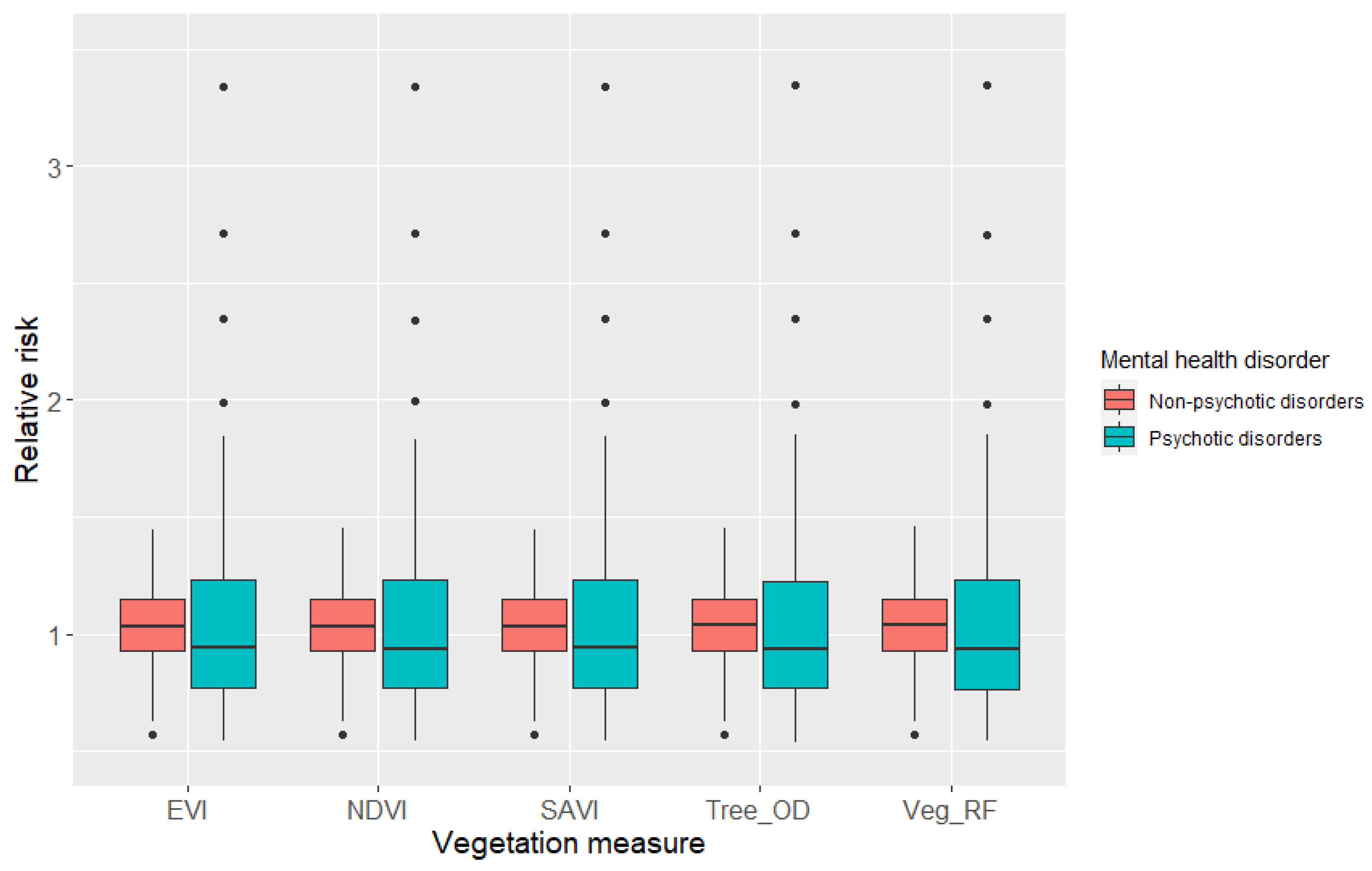

3.2. The Association between Vegetation and Psychotic and Non-Psychotic Disorders

3.3. The Spatial Distribution of the Relative Risk of Psychotic and Non-Psychotic Disorders

4. Discussions

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

- (1)

- Ontario Community Health Profiles Partnership:

- (2)

- Ontario Primary Care Need, Service Use, Providers and Teams, and Gaps in Care 2015/16:

- (3)

- USGS-EarthExplorer:

- (4)

- Open Data—Toronto (About Topographic Mapping—Treed Area):

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Markevych, I.; Schoierer, J.; Hartig, T.; Chudnovsky, A.; Hystad, P.; Dzhambov, A.M.; De Vries, S.; Triguero-Mas, M.; Brauer, M.; Nieuwenhuijsen, M.J. Exploring pathways linking greenspace to health: Theoretical and methodological guidance. Environ. Res. 2017, 158, 301–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, J.; Li, C.; Kwan, M.-P.; Chai, Y. A multilevel analysis of perceived noise pollution, geographic contexts and mental health in Beijing. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melis, G.; Gelormino, E.; Marra, G.; Ferracin, E.; Costa, G. The effects of the urban built environment on mental health: A cohort study in a large northern Italian city. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 12, 14898–14915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Mental Health: Strengthening Our Response. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/mental-health-strengthening-our-response (accessed on 10 July 2019).

- Üstün, T.B.; Ho, R. Classification of Mental Disorders: Principles and Concepts. In International Encyclopedia of Public Health, 2nd ed.; Quah, S.R., Ed.; Academic Press: Oxford, UK, 2017; pp. 51–57. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders: Clinical Descriptions and Diagnostic Guidelines; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Van Os, J.; Pedersen, C.B.; Mortensen, P.B. Confirmation of synergy between urbanicity and familial liability in the causation of psychosis. Am. J. Psychiatry 2004, 161, 2312–2314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaebel, W.; Zielasek, J. Future classification of psychotic disorders. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2009, 259, 213–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glazier, R.H.; Gozdyra, P.; Kim, M.; Bai, L.; Kopp, A.; Schultz, S.E.; Tynan, A.M. Geographic Variation in Primary Care Need, Service Use and Providers in Ontario, 2015/16; Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, M.S.D.B.J. Neurotic, stress-related and somatoform disorders. In Companion to Psychiatric Studies E-Book; Churchill Livingstone: London, UK, 2010; Volume 453. [Google Scholar]

- Fett, A.-K.J.; Lemmers-Jansen, I.L.; Krabbendam, L. Psychosis and urbanicity: A review of the recent literature from epidemiology to neurourbanism. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2019, 32, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radua, J.; Ramella-Cravaro, V.; Ioannidis, J.P.; Reichenberg, A.; Phiphopthatsanee, N.; Amir, T.; Yenn Thoo, H.; Oliver, D.; Davies, C.; Morgan, C. What causes psychosis? An umbrella review of risk and protective factors. World Psychiatry 2018, 17, 49–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CBC News. Canada’s Five Fastest Growing Urban Areas Are All in Ontario. Available online: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/windsor/stats-can-population-census-1.5075855 (accessed on 25 September 2019).

- Martellozzo, F.; Ramankutty, N.; Hall, R.J.; Price, D.T.; Purdy, B.; Friedl, M.A. Urbanization and the loss of prime farmland: A case study in the Calgary–Edmonton corridor of Alberta. Reg. Environ. Chang. 2015, 15, 881–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharpe, D.M.; Stearns, F.; Leitner, L.A.; Dorney, J.R. Fate of natural vegetation during urban development of rural landscapes in southeastern Wisconsin. Urban Ecol. 1986, 9, 267–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, M.P.; Alcock, I.; Wheeler, B.W.; Depledge, M.H. Would you be happier living in a greener urban area? A fixed-effects analysis of panel data. Psychol. Sci. 2013, 24, 920–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantler, A.; Logan, A.C. Natural environments and mental health. Adv. Integr. Med. 2015, 2, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berman, M.G.; Kross, E.; Krpan, K.M.; Askren, M.K.; Burson, A.; Deldin, P.J.; Kaplan, S.; Sherdell, L.; Gotlib, I.H.; Jonides, J. Interacting with nature improves cognition and affect for individuals with depression. J. Affect. Disord. 2012, 140, 300–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faber Taylor, A.; Kuo, F.E. Children with attention deficits concentrate better after walk in the park. J. Atten. Disord. 2009, 12, 402–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruelheide, H. Using formal logic to classify vegetation. Folia Geobot 1997, 32, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, B.; Deal, B.; Pan, H.; Larsen, L.; Hsieh, C.-H.; Chang, C.-Y.; Sullivan, W.C. Remotely-sensed imagery vs. eye-level photography: Evaluating associations among measurements of tree cover density. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2017, 157, 270–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzhambov, A.M.; Markevych, I.; Hartig, T.; Tilov, B.; Arabadzhiev, Z.; Stoyanov, D.; Gatseva, P.; Dimitrova, D.D. Multiple pathways link urban green-and bluespace to mental health in young adults. Environ. Res. 2018, 166, 223–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- USGS. Landsat Surface Reflectance-Derived Spectral Indices—Landsat Normalized Difference Vegetation Index. Available online: https://www.usgs.gov/land-resources/nli/landsat/landsat-normalized-difference-vegetation-index?qt-science_support_page_related_con=0#qt-science_support_page_related_con (accessed on 20 December 2019).

- USGS. Landsat Surface Reflectance-Derived Spectral Indices—Landsat Enhanced Vegetation Index. Available online: https://www.usgs.gov/land-resources/nli/landsat/landsat-enhanced-vegetation-index?qt-science_support_page_related_con=0#qt-science_support_page_related_con (accessed on 20 December 2019).

- Huete, A.R. A soil-adjusted vegetation index (SAVI). Remote Sens. Environ. 1988, 25, 295–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, J.R. Remote Sensing of the Environment: An Earth Resource Perspective, 2nd ed.; Pearson Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Rugel, E.J.; Henderson, S.B.; Carpiano, R.M.; Brauer, M. Beyond the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI): Developing a natural space index for population-level health research. Environ. Res. 2017, 159, 474–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsushita, B.; Yang, W.; Chen, J.; Onda, Y.; Qiu, G. Sensitivity of the enhanced vegetation index (EVI) and normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI) to topographic effects: A case study in high-density cypress forest. Sensors 2007, 7, 2636–2651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huynh, Q.; Craig, W.; Janssen, I.; Pickett, W. Exposure to public natural space as a protective factor for emotional well-being among young people in Canada. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rugel, E.J.; Carpiano, R.M.; Henderson, S.B.; Brauer, M. Exposure to natural space, sense of community belonging, and adverse mental health outcomes across an urban region. Environ. Res. 2019, 171, 365–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheppard, A.J.; Salmon, C.; Balasubramaniam, P.; Parsons, J.; Singh, G.; Jabbar, A.; Zaidi, Q.; Scott, A.; Nisenbaum, R.; Dunn, J. Are residents of downtown Toronto influenced by their urban neighbourhoods? Using concept mapping to examine neighbourhood characteristics and their perceived impact on self-rated mental well-being. Int. J. Health Geogr. 2012, 11, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gould, W. Remote sensing of vegetation, plant species richness, and regional biodiversity hotspots. Ecol. Appl. 2000, 10, 1861–1870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anselin, L. Local indicators of spatial association—LISA. Geogr. Anal. 1995, 27, 93–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haining, R.P. Spatial Autocorrelation. In International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences; Smelser, N.J., Baltes, P.B., Eds.; Pergamon: Oxford, UK, 2001; pp. 14763–14768. [Google Scholar]

- Anselin, L. Spatial dependence and spatial structural instability in applied regression analysis. J. Reg. Sci. 1990, 30, 185–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeSage, J.P. Regression analysis of spatial data. J. Reg. Anal. Pol. 1997, 27, 83–94. [Google Scholar]

- Robertson, C.; Nelson, T.A.; MacNab, Y.C.; Lawson, A.B. Review of methods for space–time disease surveillance. Spat. Spatio-Temporal Epidemiol. 2010, 1, 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, J.; Perlman, C. Exploring geographic variation of mental health risk and service utilization of doctors and hospitals in Toronto: A shared component spatial modeling approach. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, J.; Haining, R. A Bayesian approach to modeling binary data: The case of high-intensity crime areas. Geogr. Anal. 2004, 36, 197–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, J.; Haining, R.; Maheswaran, R.; Pearson, T. Analyzing the relationship between smoking and coronary heart disease at the small area level: A Bayesian approach to spatial modeling. Geogr. Anal. 2006, 38, 140–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawson, A.B. Bayesian Disease Mapping: Hierarchical Modeling in Spatial Epidemiology; Chapman and Hall/CRC: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Villeneuve, P.; Ysseldyk, R.; Root, A.; Ambrose, S.; DiMuzio, J.; Kumar, N.; Shehata, M.; Xi, M.; Seed, E.; Li, X. Comparing the normalized difference vegetation index with the Google street view measure of vegetation to assess associations between greenness, walkability, recreational physical activity, and health in Ottawa, Canada. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toronto Community Health Profiles. Toronto Health Profiles Information about TCHPP Geographies—Definitions, Notes and Historical Context. Available online: http://www.torontohealthprofiles.ca/a_documents/aboutTheData/0_2_Information_About_TCHPP_Geographies.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2019).

- Sustaining & Expanding the Urban Forest: Toronto’s Strategic Forest Management Plan; City of Toronto, Parks, Forestry and Recreation, Urban Forestry: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2013.

- Ontario Community Health Profiles Partnership. Available online: www.ontariohealthprofiles.ca (accessed on 15 March 2021).

- USGS. EarthExplorer. Available online: https://earthexplorer.usgs.gov/ (accessed on 20 December 2019).

- USGS. Landsat 8 Data Users Handbook—Section 5. Available online: https://landsat.usgs.gov/landsat-8-l8-data-users-handbook-section-5 (accessed on 20 December 2019).

- Song, C.; Woodcock, C.E.; Seto, K.C.; Lenney, M.P.; Macomber, S.A. Classification and change detection using Landsat TM data: When and how to correct atmospheric effects? Remote Sens. Environ. 2001, 75, 230–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- USGS. Landsat Surface Reflectance-Derived Spectral Indices—Landsat Soil Adjusted Vegetation Index. Available online: https://www.usgs.gov/land-resources/nli/landsat/landsat-soil-adjusted-vegetation-index (accessed on 20 December 2019).

- Peñuelas, J.; Filella, I. Visible and near-infrared reflectance techniques for diagnosing plant physiological status. Trends Plant Sci. 1998, 3, 151–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Kovacs, J.M. The application of small unmanned aerial systems for precision agriculture: A review. Precis. Agric. 2012, 13, 693–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, J.; Su, B. Significant remote sensing vegetation indices: A review of developments and applications. J. Sens. 2017, 2017, 1353691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breiman, L. Random forests. MLear 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar]

- Cutler, L.B.A. Random Forests. Available online: https://www.stat.berkeley.edu/~breiman/RandomForests/ (accessed on 5 January 2020).

- Abdullah, A.Y.M.; Masrur, A.; Adnan, M.S.G.; Baky, M.; Al, A.; Hassan, Q.K.; Dewan, A. Spatio-Temporal Patterns of Land Use/Land Cover Change in the Heterogeneous Coastal Region of Bangladesh between 1990 and 2017. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gislason, P.O.; Benediktsson, J.A.; Sveinsson, J.R. Random forests for land cover classification. Pattern Recognit. Lett. 2006, 27, 294–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puissant, A.; Rougier, S.; Stumpf, A. Object-oriented mapping of urban trees using Random Forest classifiers. IJAEO 2014, 26, 235–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randomforest: Breiman and Cutler’s Random Forests for Classification and Regression. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/randomForest/index.html (accessed on 5 January 2020).

- Open Data Portal—Toronto. About Topographic Mapping—Treed Area. Available online: https://open.toronto.ca/dataset/topographic-mapping-treed-area/ (accessed on 20 December 2019).

- Reiss, F. Socioeconomic inequalities and mental health problems in children and adolescents: A systematic review. Soc. Sci. Med. 2013, 90, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saraceno, B.; Levav, I.; Kohn, R. The public mental health significance of research on socio-economic factors in schizophrenia and major depression. World Psychiatry 2005, 4, 181. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mckenzie, S.K.; Gunasekara, F.I.; Richardson, K.; Carter, K. Do changes in socioeconomic factors lead to changes in mental health? Findings from three waves of a population based panel study. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2014, 68, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kivimäki, M.; Batty, G.D.; Pentti, J.; Shipley, M.J.; Sipilä, P.N.; Nyberg, S.T.; Suominen, S.B.; Oksanen, T.; Stenholm, S.; Virtanen, M. Association between socioeconomic status and the development of mental and physical health conditions in adulthood: A multi-cohort study. Lancet Public Health 2020, 5, e140–e149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, A.; Vega, W.C.D.; McGowan, P.O. Biological embedding in mental health: An epigenomic perspective. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2013, 91, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kataoka, S.H.; Zhang, L.; Wells, K.B. Unmet need for mental health care among US children: Variation by ethnicity and insurance status. Am. J. Psychiatry 2002, 159, 1548–1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satcher, D. Mental Health: Culture, Race, and Ethnicity—A Supplement to Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General; US Department of Health and Human Services: Washington, DC, USA, 2001.

- Bjarnason, T.; Sigurdardottir, T.J. Psychological distress during unemployment and beyond: Social support and material deprivation among youth in six northern European countries. Soc. Sci. Med. 2003, 56, 973–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matheson, F.I.; van Ingen, T. 2016 Ontario Marginalization Index: User Guide; St. Michael’s Hospital: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2018; Joint publication with Public Health Ontario.

- Benesty, J.; Chen, J.; Huang, Y.; Cohen, I. Pearson correlation coefficient. In Noise Reduction in Speech Processing; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Mansfield, E.R.; Helms, B.P. Detecting multicollinearity. Am. Stat. 1982, 36, 158–160. [Google Scholar]

- Han, B.; Gfroerer, J.C.; Colliver, J.D.; Penne, M.A. Substance use disorder among older adults in the United States in 2020. Addiction 2009, 104, 88–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reid, M.C.; Anderson, P.A. Geriatric substance use disorders. Med. Clin. N. Am. 1997, 81, 999–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, N.; Thomas, A.; Waller, L.; Conlon, E. Bayesian models for spatially correlated disease and exposure data. In Bayesian Statistics 6: Proceedings of the Sixth Valencia International Meeting, 1999; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1999; p. 131. [Google Scholar]

- Takayama, N.; Saito, H.; Fujiwara, A.; Horiuchi, M. The effect of slight thinning of managed coniferous forest on landscape appreciation and psychological restoration. Prog. Earth Planet. Sci. 2017, 4, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, P.; Banay, R.F.; Hart, J.E.; Laden, F. A review of the health benefits of greenness. Curr. Epidemiol. Rep. 2015, 2, 131–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bezold, C.P.; Banay, R.F.; Coull, B.A.; Hart, J.E.; James, P.; Kubzansky, L.D.; Missmer, S.A.; Laden, F. The relationship between surrounding greenness in childhood and adolescence and depressive symptoms in adolescence and early adulthood. Ann. Epidemiol. 2018, 28, 213–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aplin, P. Comparison of simulated IKONOS and SPOT HRV imagery for classifying urban areas. In Remotely Sensed Cities; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2003; pp. 23–45. [Google Scholar]

- Cleugh, H.; Grimmond, S. Urban climates and global climate change. In The Future of the World’s Climate, 2nd ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2011; pp. 47–76. [Google Scholar]

- Vallero, D.A. Fundamentals of Air Pollution; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Huete, A.; Didan, K.; Miura, T.; Rodriguez, E.P.; Gao, X.; Ferreira, L.G. Overview of the radiometric and biophysical performance of the MODIS vegetation indices. Remote Sens. Environ. 2002, 83, 195–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eamus, D.; Huete, A.; Yu, Q. Vegetation Dynamics; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Dadvand, P.; Bartoll, X.; Basagaña, X.; Dalmau-Bueno, A.; Martinez, D.; Ambros, A.; Cirach, M.; Triguero-Mas, M.; Gascon, M.; Borrell, C. Green spaces and general health: Roles of mental health status, social support, and physical activity. Environ. Int. 2016, 91, 161–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dzhambov, A.M. Residential green and blue space associated with better mental health: A pilot follow-up study in university students. Arch. Ind. Hyg. Toxicol. 2018, 69, 340–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartig, T. Three steps to understanding restorative environments as health resources. In Open Space: People Space; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2007; pp. 183–200. [Google Scholar]

- Sachs, J.D. From millennium development goals to sustainable development goals. Lancet 2012, 379, 2206–2211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Health in 2015: From MDGs, Millennium Development Goals to SDGs, Sustainable Development Goals; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015; ISBN 924156511X. [Google Scholar]

- Andersson, C. Public space and the new urban agenda. J. Public Space 2016, 1, 5–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Type | Sub-Category | OHIP Codes of Sub-Category |

|---|---|---|

| Psychotic disorders | Schizophrenia | 295 |

| Manic-depressive psychoses, involutional melancholia | 296 | |

| Other paranoid states | 297 | |

| Other psychoses | 298 | |

| Non-psychotic disorders | Anxiety neurosis, hysteria, neurasthenia, obsessive-compulsive neurosis, reactive depression | 300 |

| Personality disorders | 301 | |

| Sexual deviations | 302 | |

| Psychosomatic illness | 306 | |

| Adjustment reaction | 309 | |

| Depressive disorder | 311 |

| LULC Types | Description |

|---|---|

| Bare soil | Exposed soils, construction sites |

| Built-up | Residential, commercial and services, industrial, transportation, roads, mixed urban, and other urban |

| Vegetation | Deciduous forest, mixed forest lands, palms, conifer, scrub, and others |

| Waterbody | Permanent and seasonal wetlands, inland water bodies, low-lying areas, marshy land, rills and gully, swamps |

| Variables | Minimum | Mean (Standard Deviation) | Maximum |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent Variables | |||

| Number of psychotic disorders | 94 | 282.864 (±152.637) | 861 |

| Number of non-psychotic disorders | 757 | 2239.850 (±964.286) | 5523 |

| Independent Variables (vegetation) | |||

| EVI | 0.037 | 0.052 (±0.006) | 0.0679 |

| NDVI | 0.473 | 0.561 (±0.035) | 0.634 |

| SAVI | 0.041 | 0.058 (±0.006) | 0.075 |

| Percentage of vegetation cover (Veg_RF) | 0.501 | 20.730 (±13.267) | 54.279 |

| Percentage of tree cover (Tree_OD) | 0.100 | 6.540 (±5.611) | 34.117 |

| Independent Variables (others) | |||

| Material deprivation (OMI) | −1.520 | 0.250 (±0.895) | 3.068 |

| Residential instability (OMI) | −0.785 | 0.723 (±0.783) | 3.009 |

| Dependency (OMI) | −1.262 | −0.228 (±0.393) | 0.897 |

| Ethnic concentration (OMI) | −0.317 | 0.902 (±0.838) | 3.282 |

| Substance use disorder rate | 2.410 | 9.988 (±4.392) | 30.54 |

| Posterior Means Summaries | EVI | NDVI | SAVI | Veg_RF | Tree_OD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Psychotic disorders | |||||

(95% CI) | −0.287 (−0.514, −0.057) | −0.148 (−0.508, 0.206) | −0.286 (−0.513, −0.059) | −0.477 (−0.583, −0.375) | −0.492 (−0.591, −0.395) |

| (vegetation measure) (95% CI) | −4.056 (−8.147, −0.025) | −0.626 (−1.249, 0.000) | −3.676 (−7.350, −0.008) | −0.001 (−0.005, 0.004) | −0.001 (−0.006, 0.005) |

| (material deprivation) (95% CI) | 0.122 (0.077, 0.166) | 0.117 (0.073, 0.161) | 0.121 (0.076, 0.165) | 0.108 (0.062, 0.153) | 0.112 (0.068, 0.156) |

| (ethnic concentration) (95% CI) | −0.118 (−0.169, −0.064) | −0.118 (−0.169, −0.065) | −0.117 (−0.169, −0.063) | −0.121 (−0.172, −0.067) | −0.123 (−0.175, −0.067) |

| (residential instability) (95% CI) | 0.179 (0.135, 0.221) | 0.180 (0.137, 0.221) | 0.179 (0.135, 0.221) | 0.179 (0.136, 0.221) | 0.181 (0.138, 0.223) |

| (dependency) (95% CI) | −0.057 (−0.124, 0.011) | −0.057 (−0.125, 0.011) | −0.056 (−0.124, 0.012) | −0.057 (−0.126, 0.012) | −0.061 (−0.130, 0.008) |

| (substance use disorder) (95% CI) | 0.041 (0.033, 0.049) | 0.041 (0.033, 0.049) | 0.041 (0.033, 0.049) | 0.041 (0.033, 0.049) | 0.041 (0.033, 0.049) |

(95% CI) | 0.537 (0.231, 0.792) | 0.519 (0.223, 0.779) | 0.539 (0.236, 0.792) | 0.501 (0.203, 0.787) | 0.522 (0.213, 0.798) |

| 102.66 | 102.589 | 102.642 | 103.662 | 103.683 | |

| DIC | 1271.530 | 1271.580 | 1271.560 | 1272.160 | 1272.110 |

| Non-psychotic disorders | |||||

(95% CI) | 0.098 (−0.031, 0.230) | 0.015 (−0.195, 0.227) | 0.098 (−0.037, 0.236) | −0.073 (−0.135, −0.012) | −0.062 (−0.122, −0.003) |

| (vegetation measure) (95% CI) | −2.442 (−4.735, −0.172) | −0.081 (−0.446, 0.280) | −2.213 (−4.372, −0.121) | 0.002 (−0.002, 0.006) | 0.004 (−0.001, 0.008) |

| (material deprivation) (95% CI) | 0.014 (−0.014, 0.041) | 0.009 (−0.019, 0.036) | 0.013 (−0.015, 0.040) | 0.015 (−0.012, 0.041) | 0.007 (−0.020, 0.033) |

| (ethnic concentration) (95% CI) | −0.114 (−0.147, −0.082) | −0.115 (−0.148, −0.082) | −0.114 (−0.146, −0.081) | −0.115 (−0.147, −0.083) | −0.107 (−0.140, −0.075) |

| (residential instability) (95% CI) | 0.055 (0.028, 0.082) | 0.057 (0.029, 0.084) | 0.055 (0.028, 0.082) | 0.062 (0.035, 0.089) | 0.056 (0.029, 0.082) |

| (dependency) (95% CI) | 0.007 (−0.032, 0.046) | 0.006 (−0.034, 0.045) | 0.007 (−0.031, 0.046) | −0.002 (−0.041, 0.037) | 0.007 (−0.031, 0.046) |

| (substance use disorder) (95% CI) | 0.011 (0.005, 0.017) | 0.011 (0.005, 0.017) | 0.011 (0.005, 0.017) | 0.011 (0.005, 0.017) | 0.011 (0.006, 0.017) |

(95% CI) | 0.750 (0.595, 0.863) | 0.754 (0.595, 0.867) | 0.750 (0.596, 0.863) | 0.744 (0.593, 0.860) | 0.755 (0.601, 0.866) |

| 126.554 | 127.088 | 126.678 | 125.982 | 126.780 | |

| DIC | 1591.070 | 1591.540 | 1591.290 | 1590.810 | 1590.750 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Abdullah, A.Y.M.; Law, J.; Butt, Z.A.; Perlman, C.M. Understanding the Differential Impact of Vegetation Measures on Modeling the Association between Vegetation and Psychotic and Non-Psychotic Disorders in Toronto, Canada. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4713. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18094713

Abdullah AYM, Law J, Butt ZA, Perlman CM. Understanding the Differential Impact of Vegetation Measures on Modeling the Association between Vegetation and Psychotic and Non-Psychotic Disorders in Toronto, Canada. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(9):4713. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18094713

Chicago/Turabian StyleAbdullah, Abu Yousuf Md, Jane Law, Zahid A. Butt, and Christopher M. Perlman. 2021. "Understanding the Differential Impact of Vegetation Measures on Modeling the Association between Vegetation and Psychotic and Non-Psychotic Disorders in Toronto, Canada" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 9: 4713. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18094713

APA StyleAbdullah, A. Y. M., Law, J., Butt, Z. A., & Perlman, C. M. (2021). Understanding the Differential Impact of Vegetation Measures on Modeling the Association between Vegetation and Psychotic and Non-Psychotic Disorders in Toronto, Canada. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(9), 4713. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18094713