Abstract

Background: Physical activity is associated with mental health benefits. This systematic literature review summarises extant evidence regarding this association, and explores differences observed between populations over sixty-five years and those younger than sixty-five. Methods: We reviewed articles and grey literature reporting at least one measure of physical activity and at least one mental disorder, in people of all ages. Results: From the 2263 abstracts screened, we extracted twenty-seven articles and synthesized the evidence regarding the association between physical (in)activity and one or more mental health outcome measures. We confirmed that physical activity is beneficial for mental health. However, the evidence was mostly based on self-reported physical activity and mental health measures. Only one study compared younger and elder populations, finding that increasing the level of physical activity improved mental health for middle aged and elder women (no association was observed for younger women). Studies including only the elderly found a restricted mental health improvement due to physical activity. Conclusions: We found inverse associations between levels of physical activity and mental health problems. However, more evidence regarding the effect of ageing when measuring associations between physical activity and mental health is needed. By doing so, prescription of physical activity could be more accurately targeted.

1. Introduction

Over a third of the world’s population is currently affected by a mental health condition, or will be during their lives [1]. A recent report from the European Union (EU) Health Programme 2014–2020 estimates that the overall one-year prevalence of mental health disorders is around 38% [2]. Indeed, these types of disorders are the third biggest cause of disability-adjusted life years (DALY) in Europe [3]. Mental health is defined by the World Health Organization as “a state of well-being in which every individual realises his or her own potential, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively and fruitfully, and is able to make a contribution to her or his community” [4]. Several factors influence mental health. Lifestyle aspects such as physical (in)activity [5], unhealthy diets, alcohol and drug consumption [6], social context [7], work life [8], or family background [9] have been shown to impact on mental health in different contexts.

This paper focuses on the relationship between mental health (MH) and physical activity (PA). Physical activity (PA) does not only include sports and active forms of recreation (e.g., dancing), but also refers to mobility (walking and cycling), work-related activities and household tasks [5]. PA can improve physical health, self-esteem and quality of life which, in turn, enhances well-being and mental health [10]. Numerous health organisations (CDC, WHO, Health and Human Services) have outlined the benefits of physical activity, including a reduction in the risk of suffering mental health problems. Consequently, recommendations have been made on the minimum amount of activity that should be undertaken for all age groups [5]. Yet, despite the apparent benefits, 25% of all adults and 75% of teenagers (individuals aged between 11 and 17 years old) do not achieve these recommendations [5]. Physical inactivity has been defined by the WHO as a global public health problem, “partly due to people being less active during leisure time and an increase in sedentary behaviour during occupational and recreational activities” [11].

Evidence has acknowledged beneficial effects of PA on MH for the elderly [12], as well as for younger populations [13]. However, extant literature shows poor adherence rates to the prescription of PA. This non-adherence is more prominent among patients with MH [14] as well as with an increase in age [15], or for people presenting chronic diseases [16,17]. Some studies also suggested that the effect of PA on MH is stronger for elder populations than for younger adults [18]. Despite this evidence, it is rare to find papers looking at heterogeneous effects by age exploring this association between PA and MH. Additional problems found with the currently available evidence are that the studies are: (i) mostly based on self-reported measures of both PA and MH, which can lead to potential biases (e.g., [19]), (ii) when evaluating the association of PA with self-reported MH, do not analyse or distinguish respondents’ levels of self-reported MH, but treat them as a continuum (e.g., [20]); (iii) based on small sample sizes (e.g., [21]); (iv) based on cross-sectional data (e.g., [22]); or (v) purely descriptive (e.g., [23]). All of these are limitations that impede the quality of the current generation of evidence.

The aim of this paper is to explore and summarise published evidence regarding the association of PA with MH outcomes, and explore heterogeneous effects for elder and younger populations. Specific objectives are to assess whether: (i) there are differences in the association of PA with MH between the elder and younger populations; (ii) there are differences in the association of PA with MH according to the type of PA measured (objective vs. subjective); and (iii) there are differences in the association of PA with MH according to the type of MH measured (objective vs. subjective)—with a focus on clinically relevant symptoms when MH is subjective.

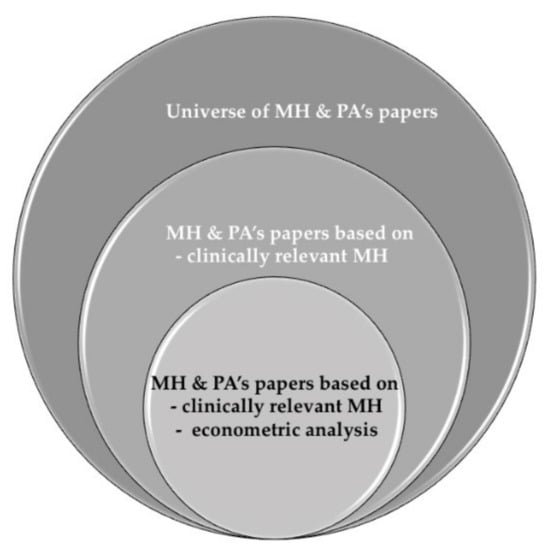

Hence, there are two main contributions from this review. First, we look for heterogeneous effects in the literature by age (below and above 65 years old). Second, we distinguish between objective and subjective measures of both PA and MH; moreover, subjective self-reported measures are distinguished by the use of validated scales. In addition, we have also identified that previous reviews lead to weak findings because they include papers based on (i) clinically irrelevant MH problems and (ii) descriptive non-robust statistical analysis. Thus, our goal is achieved by conducting a systematic literature review, focusing on studies conducting some type of econometric analysis, excluding studies that are purely descriptive, and selecting evidence based on clinically relevant MH problems. A clinically relevant MH problem is defined by validated score cut-offs for certain instruments used in the measurement of self-reported MH problems; e.g., a score over 10 points in the CES-D questionnaire is used as an indicator of clinically relevant depression symptoms in Ball et al. [24], according to a previous validation study [25]. As summarized in Figure 1, weak evidence is excluded, minimizing the risk of biased results. Imposing strong inclusion criteria (clinical characteristics and methodological restrictions) ensures better comparability among the selected studies, guaranteeing the robustness of our findings. Our selection criteria make it more likely that people self-reporting MH problems resemble clinically diagnosed patients than in the alterative situation where we might include all those other papers that use self-reported MH measures scores as a continuum, or that do not use a cut-off score. Additionally, restricting inclusion to papers using econometric methods means that the included papers provide information that can be used to establish an association of PA with MH, something that would not be possible using papers conducting purely descriptive analyses.

Figure 1.

Evidence on MH and PA.

This is the first systematic review that has filtered these analyses identifying the specific association of these practices with MH for the population that either has a clinical diagnosis of MH or has clinically relevant symptoms of MH (objectively measured).

2. Material and Methods

This systematic review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement [26]. The framework of this systematic review according to PICO [27] was: Population: people with mental health disorders, either diagnosed, or clinically relevant when self-reported; Intervention: Physical Activity of any type, objective or self-reported; Comparison: Elder and younger populations; Outcomes: effect of physical activity over mental health.

2.1. Search Strategy

We conducted our search using PubMed/Medline and EconLit as our main databases for this systematic literature review. Other sources were also consulted to complete the search with papers that were identified after reviewing some of the included records.

We applied the PICO/PECO method to structure [28] and combine keywords regarding MH (that included “Mental health”, “Mental disorder”, “Depress*”, “Anxiety”, “Psychiatr*”), as well as keywords for PA (“Physical activity”, “physical inactivity”, “Physical exertion”, “exercise”, “physical exercise”, “sport”, and “physical education”) and econometric methods (“Quantitative studies”, “quantitative analys*”, “regression”, “econometric*”, “association”, “cross-section*”, “longitudinal analys*”, “panel data analys*”, “causality*”). We excluded descriptive studies (using the words “descriptive analys*”, “ANOVA”, and “correlations measures”).

We combined these words using an algorithm and the boolean terms OR, AND, and NOT. Our PubMed/Medline and EconLit search strategy, focused on finding those records containing the following terms in titles or abstracts, is provided as Supplementary Materials.

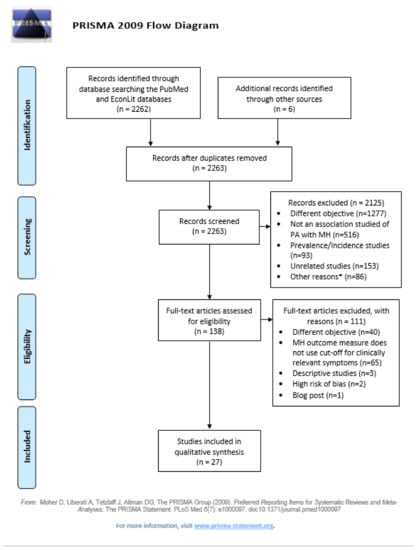

The search strategy for PubMed/Medline, EconLit and additional sources is presented in Figure 2 below. Reference lists of primary research reports were cross-checked in an attempt to identify additional studies.

Figure 2.

PRISMA flow diagram. * Other reasons for exclusion at the eligibility stage included: systematic reviews or meta-analyses (n = 48), studies of small sample size (n = 9), studies that were work in progress (n = 8), guidelines (n = 6), indirect influence of PA with MH measured only (n = 4), pilot studies (n = 3), MH outcome does not use cut-off for clinically relevant symptoms (n = 2), descriptive studies (n = 1), associations based on beliefs (n = 1), convenience sample (n = 1), not in English or Spanish (n = 1), qualitative studies (n = 1), and specific population with risk of selection bias (n = 1).

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

We limited records to any academic articles or grey literature published since 2000 available in full-text format, assessing the association of PA (whether this was objectively or subjectively measured) with MH (objectively measured, or population has at least clinically relevant symptoms). We sought studies that used econometric analysis methods (i.e., regression analysis) to establish an association of PA with MH. Papers with a different objective, and purely descriptive papers—even if they were pursuing this objective—were excluded. Studies were also excluded when investigating only symptoms of mental disorders. We did not filter for age groups in order to capture publications for all age groups, allowing comparisons by age groups. Meta-analyses, systematic reviews, methodological papers, congress proceedings, meeting abstracts and case studies were excluded from the search. We also excluded papers that presented a high risk-of-bias. All identified reasons for exclusion are detailed in the PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 2).

We consider objective and subjective measures for both PA and MH (if subjective, only those measures that are clinically relevant). Objective measures of PA are those recorded by an external technology (e.g., accelerometer recording number of steps or time spent performing the exercise) or by an exercise supervisor (e.g., coach). PA that is manually reported by the individual, for example, through a questionnaire or interview, is considered a self-reported type of PA. Regarding MH, measures are considered self-reported MH when they are not measured through a medical diagnosis. Only medical diagnoses are considered objective measures of MH. Subjective measures considered for PA and MH can be distinguished between those measured based on validated scales (e.g., IPAQ questionnaire, the only validated scale found for PA in this review, or GHQ-12 or PHQ-8, amongst others, for MH) and non-validated scales (e.g., questions for PA such as “How often are you physically active or perform exercise during your leisure time? (excluding domestic work)”), and questions for MH such as “Have you ever been diagnosed with depression?” Note that there exist other validated scales for measuring objective PA, such as the GPAQ questionnaire. However, there were no studies using the GPAQ questionnaire that satisfied the inclusion criteria specified for the objective of this review.

2.3. Study Selection and Data Extraction

After completing the search in each database, all references were imported into Zotero, the bibliographic software programme in which the study selection was conducted. The study selection included the screening of titles and abstracts in a first stage, and full-texts in a second stage, conducting a forward and backward search. The search and study selection were conducted in January 2021 by two researchers (M.E and L.M) independently from each other. Any doubts or disagreements between the two researchers were discussed with a third researcher (H.M.H.-P.). The methodology followed for data extraction was reviewed and approved by all authors. It was not necessary to contact any of the authors of the papers included in this review for completion of missing relevant information from the article.

2.4. Risk of Bias Assessment

We followed the method developed by Parmar et al. [29] for assessing the risk-of-bias of our included records. This includes seven key domains: selection bias, ecological fallacy, confounding bias, reporting bias, time bias, measurement error in exposure indicator, and measurement error in health outcome. For each publication, we rated each of the abovementioned domains: a score of 1 is given for a low risk of bias, 2 for a moderate risk and 3 for a high risk. Then, we computed the overall rating as follows: 1 (strong) was given if none of its domains were rated as weak, 2 (moderate) if up to two domains were rated as weak, or 3 (weak) if three or more domains were rated as weak.

2.5. Synthesis of Results

Data extraction from the selected papers focused on the following fields: authors and year of publication, type of study (RCT, cohort with follow-up, cross-sectional), study’s objective, sample size (and % of MH patients), age range (and mean age of the study sample), PA measure (self-reported (validated scale or not)/objective (programme)), MH problem assessed, MH Patient reported outcome (PRO) measure (self-reported (validated scale or not)/objective (clinical diagnosis)), results of the study (regarding the association of PA with MH only -all other results unrelated with these objective were not extracted-), and overall effect found for the association of PA with MH. These fields were used to construct our summary result table (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics and summary findings of the included studies.

Next, we classified studies in clusters according to the different criteria categories: age (we used 3 categories: all ages, <65 and 65+), PA type of measure (3 categories: objective, subjective validated scale, and subjective non-validated scale), and MH type of measure (3 categories: objective, subjective validated scale, and subjective non-validated scale). Thus, we ended up with 27 potential clusters. The result of this classification is summarised in Table 1 and in the Main Results section.

We limited our synthesis to studies that reported results of the association of PA with MH for a minimum sample size in each group of individuals. Our minimum study sample size requirements were (i) a minimum of 10% individuals from the total study sample with self-reported/diagnosed MH in samples with less than 100 individuals, or (ii) in samples of more than 100 individuals, a minimum of 5% of individuals with self-reported/diagnosed MH. Moreover, population-based studies representative of the general population were preferred. Alternatively, a minimum power of 0.80 and significance of 0.05 were required for a study to be able to detect group differences. Studies needed to report estimates, p-values and 95% confidence intervals from the econometric model. We only considered those studies that were moderate or strong at the quality and risk of bias assessment. The weakest studies were excluded.

We considered an association of PA with MH existed when the paper showed significant results in the econometric analyses (p-value < 0.05). When a paper explored the association of PA with MH for different population subgroups (e.g., age groups), when available, we extracted the specific information for the overall population as well as the information on the association found for each subgroup. We considered there was no association when the paper reported that no effect of PA on MH was found, or when the differences found were not statistically significant.

Finally, we summarised and interpreted our analysis according to the available combinations of PA and MH measures (PA and MH objective and/or subjective), and for the different age groups identified. This ensured the provision of the most complete interpretation of the selected studies’ results for this review.

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection

Our search strategy identified 2268 potential studies from PubMed (2249), EconLit (13) and other sources (6). After removing duplicates, 2263 abstracts remained for title and abstract screening. We excluded 2125 abstracts and selected 138 for full-text screening. Among these, only 1 paper was selected from the EconLit search, 136 were selected from the search at PubMed, and 1 paper was manually retrieved from Google scholar given our awareness of the study and its relevance. We finally extracted information from 29 papers, and excluded 2 papers after performing the risk-of-bias check. A Prisma 2009 flow diagram representing the study selection process has been presented in Figure 1.

Table 1 summarises the characteristics of the 27 studies finally included in this systematic review. Table 2 summarises the studies’ objectives and their results, including a column with the overall effect (positive, negative or none) that can be concluded after reviewing each study.

Table 2.

Evaluation of studies according to Parmar et al. (2016) [29] Risk of Bias and quality assessment.

The majority of the reviewed studies found a negative association of PA with MH, and positive for physical inactivity studies. There are two studies [30,31] that found no association of PA with MH, and a third that found association with depression symptoms, but no association for patients with anxiety [32].

3.2. Quality Assessment and the Risk of Bias

We use the Parmar et al. [29] scale for risk of bias and quality assessment. We evaluate the qualities of all included studies in the qualitative synthesis, based on a set of seven questions. Some of these questions needed to be adapted for this paper. For example, for RCTs, because representativity does not apply, we evaluate selection bias by analysing the appropriateness of the sampling methods (e.g., the study reports good power of the sampling methods reported, large-enough sample sizes, blinding, randomisation methods). Regarding confounding bias assessment, we consider stronger those studies that included an indicator of individuals taking a MH treatment as a control variable. For time bias, we consider that the longer the distance (in years) between the timeframe analysed and the time of publication, the higher the risk of time bias. A higher risk of measurement error in the exposure variable or in the MH measurement is assumed for self-reported types of PA and MH, respectively, especially when the PA/MH measurement instrument used was not a validated scale.

Each item of the bias scale was rated into one of three categories according to its risk of bias—low (for strong studies with little risk of bias), moderate, or high (weak studies with high risk of bias). When converting these elements into an overall bias score for each paper, the overall assessment of two studies was “weak”, and these were automatically excluded for the review (not shown in the summary of studies in Table 1). Among the included studies, there were fifteen strong studies (having no “weak” ratings) and twelve of moderate quality (with maximum one “weak” rating).

3.3. Main Results

Of the 27 studies included in this review, 14 (51.8%) were cross-sectional studies, 2 RCTs, and 11 follow-ups of a cohort. Different PA measures were assessed: 6 programmes of PA reporting an objective measure of PA [30,31,36,44,46,47], and the remaining 21 offering conclusions from studies based on self-reported PA. The included studies were critically assessed and their main focus was on finding an association of different types of PA with objective/clinically relevant symptoms for MH [31,39,41,46,47]. We identified in Table 1 the number of studies that used objective or self-reported, and validated vs. not validated, measures of PA and MH. Most studies used self-reported validated MH measures (85%), while for PA 48% used non-validated self-reported measures, 30% used validated measures and 22% used objective measures. There were only 4 studies presenting results for the elderly, and they all used validated self-reported MH measures. There was only a minority of 5 studies that, when measuring the association of PA with MH, accounted (as a confounding factor) for some type of MH treatment [31,39,41,46,47].

3.3.1. Differences in the Association of PA with MH between Elder and Younger Populations

Among the 27 studies included, 14 included elder populations of 65 years or over [31,32,33,34,35,36,37,39,42,44,45,51,54]. However, only 2 studies [17,40] included as covariates the interaction between age groups and PA to facilitate the comparison across age groups of PA on MH. In particular, Griffiths et al. [40] found a lower risk of mental ill-health for mid-life (AOR = 0.81 (0.66–0.99) for ≥60 MET hours/week) and older women (OR = 0.77 (0.55–1.07) for ≥60 MET hours/week) who reported increased levels of physical activity than those who did not increase physical activity.

There were 9 studies that [32,33,35,36,39,44,49,51,54] included age as a control variable, but the analysis was performed in a way that did not allow any conclusions to be made regarding the differences in the association of PA with MH between the elder and the younger populations. One study, Hamer et al. [18], observed slightly stronger associations of PA with self-reported MH in participants >60years of age or with chronic conditions.

The study of Bishwajit et al. [35] is based on self-reported PA while Karg et al. [46] is based on objectively measured PA (programme). Bishwajit et al. [35] found, for the population aged 50 and older (mean age ~ 60, SD ~9), that those who reported never engaging in self-reported moderate or vigorous PA had ORs clearly higher for diagnosed depression than those who engaged in moderate or vigorous PA. Karg et al. [46], who focused on a middle-aged population (mean age = 42, SD = 12.5), found support for previous findings suggesting positive effects of physical activity and particularly bouldering in depressed individuals. This study also controlled for participants’ current therapeutic treatment, in addition to the prescribed PA. Comparing ORs for both studies, the effect is higher in the bouldering therapy programme [46]. One should take into account that their population is also slightly younger.

3.3.2. Differences in the Association of PA with MH between Self-Reported and Objective Types of MH

There were only 2 studies out of the 27 that included a population with a clinically diagnosed mental health disorder [35,46]. The remaining twenty-five studies assessed self-reported mental health using validated scales, with the most frequent the GHQ-12 (n = 4 studies) ahead of the GDS-15 (n = 3), CES-D (n = 3), PHQ-9 (n = 2), and the SF-36 (n = 2). All of the papers selected for this review which analysed the association of PA with MH based on self-reported MH used a MH cut-off score, meaning their MH measures should be considered as the probable presence of a MH problem. As is common in the literature, when an individual scores above that cut-off, this individual was considered to have clinically relevant symptoms of a MH disorder. We also included 2 studies [38,53] that, even though they used a validated MH scale, did not use a specific cut-off but rather performed analysis by categories of severity of symptoms.

Among the 25 studies based on populations’ clinically relevant symptoms of MH as identified by self-reported mental health measures, 18 studies concluded that there was an unconditional, negative association between PA levels and MH prevalence, fifteen of them indicating PA is beneficial for MH, and three indicating physical inactivity worsens MH; 1 study reported differences between PA but only for depression, not for anxiety [32]; 1 study found that PA is especially beneficial for the MH of the elder population. Finally, 1 study found a beneficial but only for women [31]. Two studies did not find an association of PA with MH [30,31].

3.3.3. Differences in the Association of PA with MH for Self-Reported and Objective Types of PA

Among the 27 studies reviewed and analysed, four assessed impact on MH with an objective measure of PA [30,31,36,46]. Objective measures of PA included supervised exercise programmes, accelerometer/activity monitor, and bouldering psychotherapy. The majority of studies (N = 21, 77.7%) assessed the association with MH using a self-reported measure of PA. The most repeated instrument for self-recording PA time was the IPAQ questionnaire (n = 3), while all other studies used different questions to assess time dedicated to PA. Among the studies using a self-reported measure of PA, 3 assessed physical inactivity [44,49,50], and all them found it was associated with adverse MH.

Of the 4 studies using objective PA, 2 found that higher PA was associated with lower levels of poor MH [36,46], and 2 found no effect, one of which studied an elderly population [31] and the other a population of post-partum women [30]. Within the self-reported PA measures, more PA led to better MH in 18 studies, and more physical inactivity led to worse MH in three studies. Fourteen studies conclude that this effect of PA is persistent without restrictions. A similar effect was identified but with some restrictions, for PA, in four studies. Some techniques were found to be more effective than others [37], or MH might be effective for depression but not for anxiety [29], or it showed effectiveness especially on a subgroup of the population (e.g., aged > 60 or with chronic conditions, as in one of the studies [18], or for women only [33]). Two studies conclude there was no association of PA with MH [30,31].

4. Discussion

This systematic review aimed to present and rigorously assess the evidence available on the association of PA with MH and differences by (i) age groups (elder and younger populations), (ii) type of MH (self-reported and objectively measured), and (iii) type of PA measure (objective vs. self-reported) in order to identify literature gaps, document the current leading-edge knowledge, and open a discussion regarding the direction in which further research should move. Our review results indicate that physical activity is beneficial for mental health. However, the evidence was mostly based on self-reported physical activity and mental health measures, and did not allow to really compare results between younger adults and adults aged 65 or over.

Given the number of abstracts captured by our search strategy, one could think that there exists an extensive literature on the association between PA and MH outcomes. However, a large number of studies were excluded (N = 65 excluded records at the full-text screening phase, representing 47.1% of all the full-text screened records, as stated in Figure 1) because they included in their analytic samples individuals who had low MH symptoms as well as those with probable MH issues [55], despite the differences between these two populations. Failing to account for this weakness reduces the validity and precision of previous reviews.

Imposing this strong inclusion criterion is based on medical literature. There is evidence suggesting people clinically diagnosed with MH and people who self-report to be suffering from MH are very different [56,57]. In addition, despite the validity of the instruments that could be used to identify self-reporting people with clinically relevant symptoms of MH, most published papers ignore the fact that these two populations (reaching or not the cut-off) are different, and treat them without making a distinction (e.g., [58,59,60] and many others). Different cut-offs are recommended, specific for each scale or instrument, to assess the severity of MH disorders, and to distinguish people who would be very likely to be diagnosed with a MH disorder from those with less severe MH symptoms. Although for some instruments the cut-off points are still unclear [61], there are now many instruments that have been validated and for which high degrees of sensitivity have been demonstrated [62,63]. In consequence, studies like Zang et al. [54] have demonstrated significantly different associations of PA with MH for individuals with self-reported but not-clinically relevant symptoms, and for those with clinically relevant symptoms. In spite of evidence to support the validated cutoffs used to screen for MH problems linked to clinically relevant symptoms [57], the papers we exclude from our study ignore them. Instead, they treat MH outcome scores as continuous variables when exploring the effect of PA on self-reported MH, or on mental health scores that are not confirmed by a clinician [64]. These studies group all of the participants who self-report an MH problem in the same category as those with a clinical diagnosis of MH, which is imprecise and weak.

Literature has also found consistently that moderate-to-vigorous intensity physical activity improves MH of the mentally-ill [35,36,37,65]. Physical activity could, indeed, be an effective measure for both preventing and treating MH. While psychotropic medications are still the main treatment for most MH disorders [66] a growing body of scientific evidence strongly supports the role of exercise in the treatment regime [67]. For example, Zhang and Yen [54] used econometric models to demonstrate that physical activity remedies the depressive symptoms amongst individuals suffering from mild and moderate depression. Although Lordan et al. [68] confirmed these results and added that the impact is even greater for women, their study was based upon a population with MH symptoms, with no screening indicator for the clinical relevance of such symptoms. Physical activity remedying depressive symptoms has also been analysed through different categories such as green spaces, group exercise, the elderly, youth, gender and countries/regions. However, the association of these with populations suffering from MH problems, or with, at least, probable MH problems is still uncertain.

This is the first systematic review, to our knowledge, assessing the association of PA with MH combining studies of populations with diagnosed MH and those with self-reported MH and clinically relevant symptoms. We believe including the subsample of people with probable MH is important given their proximity to MH diagnosis.

Indeed, if we compare the results observed in those studies using patients clinically diagnosed with MH against results from studies using self-reported clinically relevant MH measures, we observe similar findings. In particular, the two studies using populations of patients with a MH diagnosis, and twenty-one out of the twenty-five studies using self-reported clinically relevant MH measures, found a negative and unconditional association between levels of PA with levels of MH, indicating that PA is beneficial for MH (and (in)PA worsens MH). The remaining four studies using self-reported MH measures found a conditional association, for example, that some therapies would work better than others to help patients with MH.

In addition to this, we designed our study selection and search strategy to ensure that we captured populations of all ages within our studies. Therefore, we were able to use age as a comparison factor, putting our focus on the differences of the association of PA with MH between elder and younger populations. Although our review provides evidence indicating PA is beneficial for MH, we observe that the intensity of such a relationship varies by the type of PA and MH measured, as well as by age. The number of studies offering a cut-off distinguishing clinically relevant symptoms from less important symptoms of MH is small compared to the number of studies that use MH self-reported outcome measures without making this distinction. These findings suggest that more evidence is needed regarding (1) the association of physical activities with mental health for people of different ages; and (2) in people with probable MH, ignoring the similarity between this population and the population with a clinical diagnosis on MH. Another gap we identify in the literature is the lack of longitudinal studies, with most studies analysing cross-sectional data or short-term follow-ups. This creates a barrier to establishing causality in the analyses of the association between PA and MH. We, thus encourage further studies to use validated cut-offs to provide analyses of people with possible MH in the future.

Our paper has some limitations. First, we did not include papers published before 2000. However, the time constraint decision lies on the fact that most of the MH measures including a cut-off to distinguish for clinically relevant symptoms were validated after the year 2000. Hence, we considered that a search focused on 2000 and onwards papers would be more accurate. Second, our analysis is not purely based on clinically diagnosed MH, the most accurate measure of MH, given the low number of published studies with clinically diagnosed populations (n = 2). Thus, we also included papers based on population with clinically relevant symptoms of MH. Yet, these clinically relevant symptom cut-offs were created specifically to indicate the high probability of individuals to be diagnosed in the early future, which mitigates, somewhat, this limitation.

5. Conclusions

We found inverse associations between PA and MH. However, research designs are often weak, based mostly on self-reported measures of PA and MH, and effects are small to moderate. Effect by age seems to be scarce when measuring the differences in the association of PA with MH. More studies are required to provide an accurate estimate of the association of PA with MH, using more robust methods which can be externally verified for different populations. In order to better target and effectively prescribe PA, more evidence comparing elder and younger populations, and the specific populations with probable MH, is required.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/ijerph18094771/s1, Supplementary tables of the data extraction process and risk-of-bias assessment can be provided upon request.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the design of the search strategy and approved it. M.E.R. and L.M. conducted the studies’ selection and data extraction. H.M.H.-P. acted as a third reviewer when there was a disagreement between M.E.R. and L.M. on the studies’ selection and data extraction processes. M.E.R. conducted the analyses. The content of the data extraction and analyses were approved by L.M. and H.M.H.-P. All authors were involved in the writing and review of the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This project was funded by “la Caixa” Foundation agreement LCF/PR/CE07/50610001. H.M.H.-P. received financial support from “Secretaria d’Universitats i Recerca del Departament d’Economia i Coneixement de la Generalitat de Catalunya” grant number AGAUR Consolidated Research Group 2017 SGR 1059. The APC was funded by London School of Economics and Political Science.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The project leading to these results has received funding from “la Caixa” Foundation, under agreement LCF/PR/CE07/50610001. Helena belongs to AGAUR Consolidated Research Group 2017 SGR 1059 and received financial support from “Secretaria d’Universitats i Recerca del Departament d’Economia i Coneixement de la Generalitat de Catalunya”. We gratefully acknowledge the contribution of Marlene Herisson and Marc Saez in a first version of the manuscript. We would also like to thank Alba Pardo for her valuable comments.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Steel, J.L.; Cheng, H.; Pathak, R.; Wang, Y.; Miceli, J.; Hecht, C.L.; Haggerty, D.; Peddada, S.; Geller, D.A.; Marsh, W.; et al. Psychosocial and Behavioral Pathways of Metabolic Syndrome in Cancer Caregivers. Psychooncology 2019, 28, 1735–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbato, A.; Vallarino, M.; Rapisarda, F.; Lora, A.; Caldas de Almeida, J. Access to Mental Health Care in Europe—Scientific Paper; EU Compass for Action on Mental Health and Well-Being; Funded by the European Union in the frame of the 3rd EU Health Programme (2014–2020); Trimbos Institute: Utrecht, The Netherlands; NOVA University of Lisbon: Lisbon, Portugal; Finish Association for Mental Health: Helsinki, Finland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe. Mental Health; Fact Sheets on Sustainable Development Goals: Health Targets; WHO Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. WHO | Mental Health. Available online: http://www.who.int/research-observatory/analyses/mentalhealth/en/ (accessed on 19 February 2021).

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development; World Health Organization; World Bank Group. Delivering Quality Health Services: A Global Imperative for Universal Health Coverage; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2018; ISBN 978-92-64-30030-9. [Google Scholar]

- Velten, J.; Bieda, A.; Scholten, S.; Wannemüller, A.; Margraf, J. Lifestyle Choices and Mental Health: A Longitudinal Survey with German and Chinese Students. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, K.S. Social Context and Mental Health, Distress and Illness: Critical yet Disregarded by Psychiatric Diagnosis and Classification. Indian J. Psychiatry 2016, 32, 243–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.-M.; Cho, S. Socioeconomic Status, Work-Life Conflict, and Mental Health. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2020, 63, 703–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appelqvist-Schmidlechner, K.; Tamminen, N.; Solin, P. Association between Positive Mental Health and Family Background among Young People in Finland. Eur. J. Public Health 2019, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalayondeja, C.; Jalayondeja, W.; Suttiwong, J.; Sullivan, P.E.; Nilanthi, D.L. Physical Activity, Self-Esteem, and Quality of Life among People with Physical Disability. Southeast Asian J. Trop. Med. Public Health 2016, 47, 546–558. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- NCDs | Physical Inactivity: A Global Public Health Problem. Available online: http://www.who.int/ncds/prevention/physical-activity/inactivity-global-health-problem/en/ (accessed on 3 March 2021).

- Pavlova, I.; Vovkanych, L.; Vynogradskyi, B. Physical Activity of Elderly People. Physiotherapy 2014, 22, 78745660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Rodriguez-Ayllon, M.; Cadenas-Sánchez, C.; Estévez-López, F.; Muñoz, N.E.; Mora-Gonzalez, J.; Migueles, J.H.; Molina-García, P.; Henriksson, H.; Mena-Molina, A.; Martínez-Vizcaíno, V.; et al. Role of Physical Activity and Sedentary Behavior in the Mental Health of Preschoolers, Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sports Med. Auckl. N. Z. 2019, 49, 1383–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jack, K.; McLean, S.M.; Moffett, J.K.; Gardiner, E. Barriers to Treatment Adherence in Physiotherapy Outpatient Clinics: A Systematic Review. Man. Ther. 2010, 15, 220–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, D.; Archer, T. Positive Affect and Age as Predictors of Exercise Compliance. PeerJ 2014, 2, e694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Lukács, A.; Mayer, K.; Juhász, E.; Varga, B.; Fodor, B.; Barkai, L. Reduced Physical Fitness in Children and Adolescents with Type 1 Diabetes: Reduced Physical Fitness in Youths with Type 1 Diabetes. Pediatr. Diabetes 2012, 13, 432–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maggio, A.B.R.; Hofer, M.F.; Martin, X.E.; Marchand, L.M.; Beghetti, M.; Farpour-Lambert, N.J. Reduced Physical Activity Level and Cardiorespiratory Fitness in Children with Chronic Diseases. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2010, 169, 1187–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamer, M.; Biddle, S.J.H.; Stamatakis, E. Weekend Warrior Physical Activity Pattern and Common Mental Disorder: A Population Wide Study of 108,011 British Adults. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2017, 14, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spitzer, S.; Weber, D. Reporting Biases in Self-Assessed Physical and Cognitive Health Status of Older Europeans. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0223526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagatun, Å.; Heyerdahl, S.; Wentzel-Larsen, T.; Lien, L. Medical Benefits in Young Adulthood: A Population-Based Longitudinal Study of Health Behaviour and Mental Health in Adolescence and Later Receipt of Medical Benefits. BMJ Open 2015, 5, e007139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker, J.G.; Leddy, J.J.; Hinds, A.L.; Haider, M.N.; Shucard, J.; Sharma, T.; Hernandez, S.; Durinka, J.; Zivadinov, R.; Willer, B.S. An Exploratory Study of Mild Cognitive Impairment of Retired Professional Contact Sport Athletes. J. Head Trauma Rehabil. 2018, 33, E16–E23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asefa, A.; Nigussie, T.; Henok, A.; Mamo, Y. Prevalence of Sexual Dysfunction and Related Factors among Diabetes Mellitus Patients in Southwest Ethiopia. BMC Endocr. Disord. 2019, 19, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallberg, I.; Bachrach-Lindström, M.; Hammerby, S.; Toss, G.; Ek, A.-C. Health-Related Quality of Life after Vertebral or Hip Fracture: A Seven-Year Follow-up Study. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2009, 10, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, K.; Burton, N.W.; Brown, W.J. A Prospective Study of Overweight, Physical Activity, and Depressive Symptoms in Young Women. Obesity 2009, 17, 66–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andresen, E.M.; Malmgren, J.A.; Carter, W.B.; Patrick, D.L. Screening for Depression in Well Older Adults: Evaluation of a Short Form of the CES-D. Am. J. Prev. Med. 1994, 10, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; Prisma Group. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sackett, D.L.; Strauss, S.E.; Richardson, W.S.; Rosenberg, W.; Haynes, R.B. Evidence-Based Medicine: How to Practice and Teach EBM, 2nd ed.; Elsevier: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2000; Volume 16. [Google Scholar]

- Da Costa, D.; Zelkowitz, P.; Dasgupta, K.; Sewitch, M.; Lowensteyn, I.; Cruz, R.; Hennegan, K.; Khalifé, S. Dads Get Sad Too: Depressive Symptoms and Associated Factors in Expectant First-Time Fathers. Am. J. Mens Health 2017, 11, 1376–1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmar, D.; Stavropoulou, C.; Ioannidis, J.P.A. Health Outcomes during the 2008 Financial Crisis in Europe: Systematic Literature Review. BMJ 2016, 354, i4588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coll, C.d.V.N.; Domingues, M.R.; Stein, A.; da Silva, B.G.C.; Bassani, D.G.; Hartwig, F.P.; da Silva, I.C.M.; da Silveira, M.F.; da Silva, S.G.; Bertoldi, A.D. Efficacy of Regular Exercise During Pregnancy on the Prevention of Postpartum Depression: The PAMELA Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw. Open 2019, 2, e186861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Underwood, M.; Lamb, S.E.; Eldridge, S.; Sheehan, B.; Slowther, A.-M.; Spencer, A.; Thorogood, M.; Atherton, N.; Bremner, S.A.; Devine, A.; et al. Exercise for Depression in Elderly Residents of Care Homes: A Cluster-Randomised Controlled Trial. Lancet Lond. Engl. 2013, 382, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shigdel, R.; Stubbs, B.; Sui, X.; Ernstsen, L. Cross-Sectional and Longitudinal Association of Non-Exercise Estimated Cardiorespiratory Fitness with Depression and Anxiety in the General Population: The HUNT Study. J. Affect. Disord. 2019, 252, 122–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Annerstedt, M.; Ostergren, P.-O.; Björk, J.; Grahn, P.; Skärbäck, E.; Währborg, P. Green Qualities in the Neighbourhood and Mental Health—Results from a Longitudinal Cohort Study in Southern Sweden. BMC Public Health 2012, 12, 337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedetti, T.R.B.; Borges, L.J.; Petroski, E.L.; Gonçalves, L.H.T. Physical Activity and Mental Health Status among Elderly People. Rev. Saúde Pública 2008, 42, 302–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishwajit, G.; O’Leary, D.P.; Ghosh, S.; Yaya, S.; Shangfeng, T.; Feng, Z. Physical Inactivity and Self-Reported Depression among Middle- and Older-Aged Population in South Asia: World Health Survey. BMC Geriatr. 2017, 17, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blumenthal, J.A.; Babyak, M.A.; O’Connor, C.; Keteyian, S.; Landzberg, J.; Howlett, J.; Kraus, W.; Gottlieb, S.; Blackburn, G.; Swank, A.; et al. Effects of Exercise Training on Depressive Symptoms in Patients with Chronic Heart Failure: The HF-ACTION Randomized Trial. JAMA 2012, 308, 465–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byeon, H. Relationship between Physical Activity Level and Depression of Elderly People Living Alone. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, A.H.; Lee, J.J.; Chmiel, J.S.; Almagor, O.; Song, J.; Sharma, L. Association of Long-Term Strenuous Physical Activity and Extensive Sitting With Incident Radiographic Knee Osteoarthritis. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e204049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, M.; Snaedal, J.; Einarsson, B.; Bjornsson, S.; Saczynski, J.S.; Aspelund, T.; Garcia, M.; Gudnason, V.; Harris, T.B.; Launer, L.J.; et al. The Association Between Midlife Physical Activity and Depressive Symptoms in Late Life: Age Gene/Environment Susceptibility-Reykjavik Study. J. Gerontol. A. Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2016, 71, 502–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Chen, X.; Lu, W.; Zheng, Y.; Gu, K.; Chen, Z.; Zheng, W.; Shu, X.O. Exercise, Tea Consumption, and Depression among Breast Cancer Survivors. J. Clin. Oncol. Off. J. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. 2010, 28, 991–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, Q.; Zhang, Q.; Du, Y.; Ye, Y.; He, Q. Associations of Physical Activity, Screen Time with Depression, Anxiety and Sleep Quality among Chinese College Freshmen. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e100914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, A.; Kouvonen, A.; Pentti, J.; Oksanen, T.; Virtanen, M.; Salo, P.; Väänänen, A.; Kivimäki, M.; Vahtera, J. Association of Physical Activity with Future Mental Health in Older, Mid-Life and Younger Women. Eur. J. Public Health 2014, 24, 813–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guddal, M.H.; Stensland, S.Ø.; Småstuen, M.C.; Johnsen, M.B.; Zwart, J.-A.; Storheim, K. Physical Activity and Sport Participation among Adolescents: Associations with Mental Health in Different Age Groups. Results from the Young-HUNT Study: A Cross-Sectional Survey. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e028555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamer, M.; Coombs, N.; Stamatakis, E. Associations between Objectively Assessed and Self-Reported Sedentary Time with Mental Health in Adults: An Analysis of Data from the Health Survey for England. BMJ Open 2014, 4, e004580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanamori, S.; Takamiya, T.; Inoue, S.; Kai, Y.; Tsuji, T.; Kondo, K. Frequency and Pattern of Exercise and Depression after Two Years in Older Japanese Adults: The JAGES Longitudinal Study. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 11224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karg, N.; Dorscht, L.; Kornhuber, J.; Luttenberger, K. Bouldering Psychotherapy Is More Effective in the Treatment of Depression than Physical Exercise Alone: Results of a Multicentre Randomised Controlled Intervention Study. BMC Psychiatry 2020, 20, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, W.C.; Kalarchian, M.A.; Steffen, K.J.; Wolfe, B.M.; Elder, K.A.; Mitchell, J.E. Associations between Physical Activity and Mental Health among Bariatric Surgical Candidates. J. Psychosom. Res. 2013, 74, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koo, K.-M.; Kim, K. Effects of Physical Activity on the Stress and Suicidal Ideation in Korean Adult Women with Depressive Disorder. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, J.Y.; Kim, J.; Cho, K.H.; Choi, J.; Shin, J.; Park, E.-C. The Impact of Sitting Time and Physical Activity on Major Depressive Disorder in South Korean Adults: A Cross-Sectional Study. BMC Psychiatry 2017, 17, 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pengpid, S.; Peltzer, K. Leisure-Time Sedentary Behavior Is Associated with Psychological Distress and Substance Use among School-Going Adolescents in Five Southeast Asian Countries: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steinmo, S.; Hagger-Johnson, G.; Shahab, L. Bidirectional Association between Mental Health and Physical Activity in Older Adults: Whitehall II Prospective Cohort Study. Prev. Med. 2014, 66, 74–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Gool, C.H.; Kempen, G.I.J.M.; Bosma, H.; van Boxtel, M.P.J.; Jolles, J.; van Eijk, J.T.M. Associations between Lifestyle and Depressed Mood: Longitudinal Results from the Maastricht Aging Study. Am. J. Public Health 2007, 97, 887–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vankim, N.A.; Nelson, T.F. Vigorous Physical Activity, Mental Health, Perceived Stress, and Socializing among College Students. Am. J. Health Promot. AJHP 2013, 28, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Ting, R.Z.; Yang, W.; Jia, W.; Li, W.; Ji, L.; Guo, X.; Kong, A.P.; Wing, Y.-K.; Luk, A.O.; et al. Depression in Chinese Patients with Type 2 Diabetes: Associations with Hyperglycemia, Hypoglycemia, and Poor Treatment Adherence. J. Diabetes 2015, 7, 800–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, R.L.; Bennie, J.; Abbott, G.; Teychenne, M. Work-Related Physical Activity and Psychological Distress among Women in Different Occupations: A Cross-Sectional Study. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, J.-Y.; Lee, S.K.; Kang, Y.-W.; Jang, S.-N.; Choi, Y.J.; Kim, D.-H. Relationship between ED and Depression among Middle-Aged and Elderly Men in Korea: Hallym Aging Study. Int. J. Impot. Res. 2011, 23, 227–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiely, K.M.; Butterworth, P. Validation of Four Measures of Mental Health against Depression and Generalized Anxiety in a Community Based Sample. Psychiatry Res. 2015, 225, 291–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, P.; Doré, I.; Romain, A.-J.; Hains-Monfette, G.; Kingsbury, C.; Sabiston, C. Dose Response Association of Objective Physical Activity with Mental Health in a Representative National Sample of Adults: A Cross-Sectional Study. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0204682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautam, R.; Saito, T.; Kai, I. Leisure and Religious Activity Participation and Mental Health: Gender Analysis of Older Adults in Nepal. BMC Public Health 2007, 7, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J.; McDowell, C.; Lansing, J.; Brower, C.; Smith, L.; Tully, M.; Herring, M. Changes in Physical Activity and Sedentary Behavior in Response to COVID-19 and Their Associations with Mental Health in 3052 US Adults. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunstan, D.A.; Scott, N. Clarification of the Cut-off Score for Zung’s Self-Rating Depression Scale. BMC Psychiatry 2019, 19, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makowska, Z.; Merecz, D.; Mościcka, A.; Kolasa, W. The Validity of General Health Questionnaires, GHQ-12 and GHQ-28, in Mental Health Studies of Working People. Int. J. Occup. Med. Environ. Health 2002, 15, 353–362. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Salinas-Rodríguez, A.; Manrique-Espinoza, B.; Acosta-Castillo, G.I.; Franco-Núñez, A.; Rosas-Carrasco, O.; Gutiérrez-Robledo, L.M.; Sosa-Ortiz, A.L. Validation of a cutoff point for the short version of the Depression Scale of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies in older Mexican adults. Salud Publica Mex. 2014, 56, 279–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, J.V.; Sera, F.; Cummins, S.; Flouri, E. Associations between Objectively Measured Physical Activity and Later Mental Health Outcomes in Children: Findings from the UK Millennium Cohort Study. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2018, 72, 94–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, K.W.; Chen, C.-Y.; Stein, M.B.; Klimentidis, Y.C.; Wang, M.-J.; Koenen, K.C.; Smoller, J.W. Major Depressive Disorder Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium Assessment of Bidirectional Relationships Between Physical Activity and Depression Among Adults: A 2-Sample Mendelian Randomization Study. JAMA Psychiatry 2019, 76, 399–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frank, R.G.; Conti, R.M.; Goldman, H.H. Mental Health Policy and Psychotropic Drugs. Milbank Q. 2005, 83, 271–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zschucke, E.; Gaudlitz, K.; Ströhle, A. Exercise and Physical Activity in Mental Disorders: Clinical and Experimental Evidence. J. Prev. Med. Public Health 2013, 46, S12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lordan, G.; Pakrashi, D. Make Time for Physical Activity or You May Spend More Time Sick! Soc. Indic. Res. 2014, 119, 1379–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).