Mental Health and Well-Being Needs among Non-Health Essential Workers during Recent Epidemics and Pandemics

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Formulating the Research Question

- (1)

- What were the mental health effects on non-health essential workers during pandemics in the last 20 years (2000–2020)?

- (2)

- What were the factors affecting their mental health (including those related to the onset of their mental health issues and those that aggravated and alleviated the mental health effects)?

- (3)

- What were their coping strategies to combat the mental health effects?

2.2. Identifying Relevant Studies

2.3. Study Selection

2.4. Data Extraction, Charting, and Synthesis

2.5. Interpreting and Reporting Results

3. Results

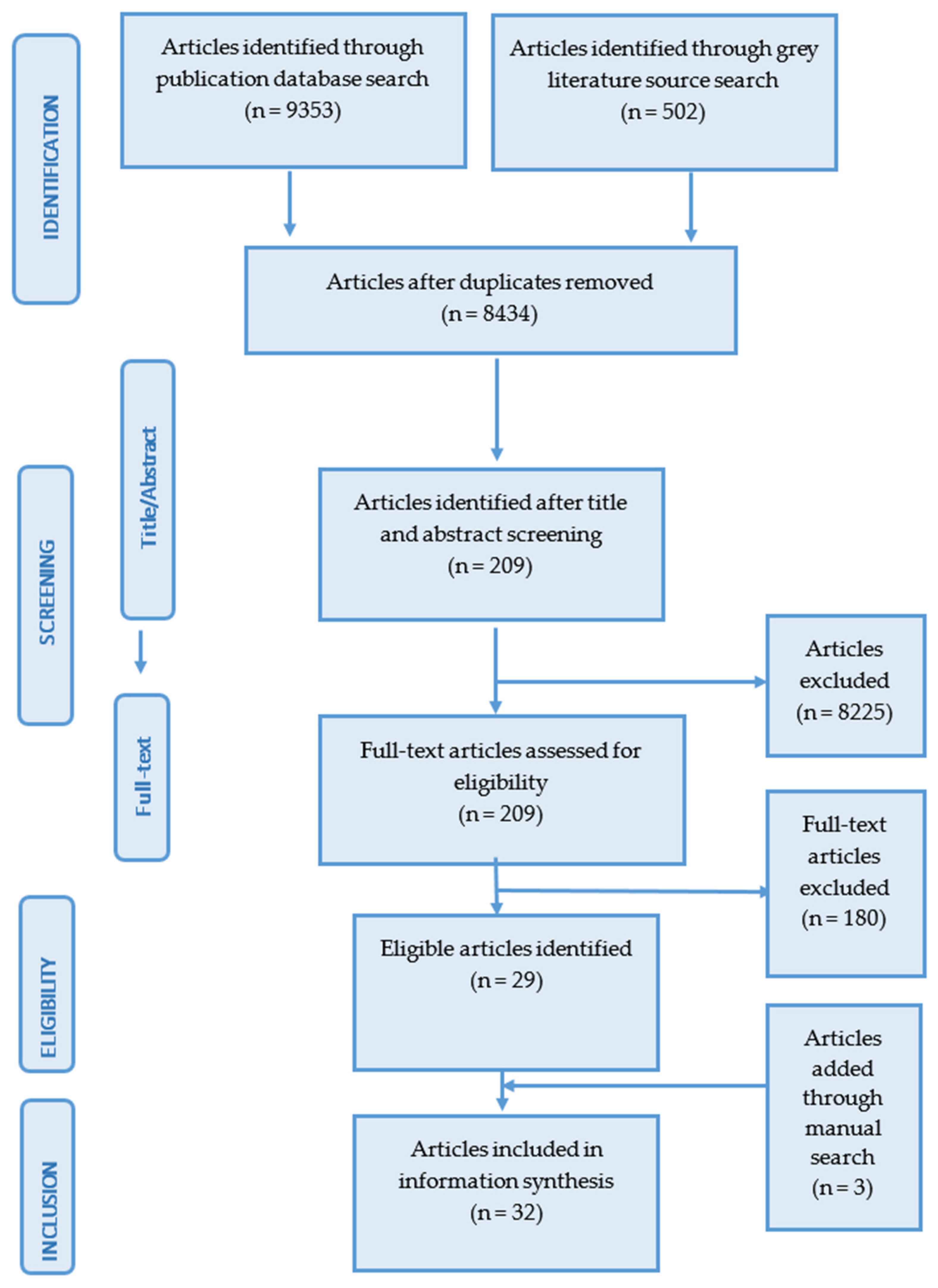

3.1. Literature Search Overview

3.1.1. Content Overview

3.1.2. Mental Health Issues

3.1.3. Instruments Used for Identifying the Mental Health Issues

3.1.4. Study Objectives

3.1.5. Data Collection Strategies

3.1.6. Outbreaks

3.2. Mental Health Effects of Outbreaks by Non-Health Essential Occupations

3.2.1. Factory and Production Occupations

3.2.2. Farming, Fishing, Agriculture, and Forestry Occupations

3.2.3. Food Preparation and Serving Occupations

3.2.4. Installation, Maintenance, Cleaning, and Repair Workers

3.2.5. Protective Service Occupations

3.2.6. Sales and Related Occupations

3.2.7. Social Care Practice and Support

3.2.8. Transportation and Delivery Occupations

3.2.9. Other

3.3. Factors

3.3.1. Demographic Factors

Age

Sex, Gender, and Sexual Orientation

Marital Status

Education Level

Regions

Financial Status and Expenses

3.3.2. Work-Related Factors

Risk of Exposure

Increased Work Hours and Workload

Being Unable to Care for Children and See Families

Lack of Workplace Support

3.3.3. Other Factors

3.4. Coping Strategies

3.4.1. Individual-Initiated Coping Strategies

3.4.2. Available Support

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- The Lancet. The plight of essential workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet 2020, 395, 1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blau, F.D.; Kobe, J.; Meyerhofer, P.A. Essential and Frontline Workers in the COVID-19 Crisis|Econofact. 2020. Available online: https://econofact.org/essential-and-frontline-workers-in-the-covid-19-crisis (accessed on 23 August 2021).

- Public Safety Canada. Guidance on Essential Services and Functions in Canada during the COVID-19 Pandemic. 2020. Available online: https://www.publicsafety.gc.ca/cnt/ntnl-scrt/crtcl-nfrstrctr/esf-sfe-en.aspx (accessed on 23 August 2021).

- Robillard, R.; Saad, M.; Edwards, J.D.; Solomonova, E.; Pennestri, M.H.; Daros, A.; Veissière, S.P.L.; Quilty, L.; Dion, K.; Nixon, A.; et al. Social, Financial and Psychological Stress during an Emerging Pandemic: Observations from a Population Web-Based Survey in the acute phase of the COVID-19 pandemic. Medrxiv 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chew, N.W.S.; Lee, G.K.H.; Tan, B.Y.Q.; Jing, M.; Goh, Y.; Ngiam, N.J.H.; Yeo, L.L.L.; Ahmad, A.; Ahmed Khan, F.; Napolean Shanmugam, G.N.; et al. A multinational, multicentre study on the psychological outcomes and associated physical symptoms amongst healthcare workers during COVID-19 outbreak. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020, 88, 559–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Kock, J.H.; Latham, H.A.; Leslie, S.J.; Grindle, M.; Munoz, S.-A.; Ellis, L.; Polson, R.; O’Malley, C.M. A rapid review of the impact of COVID-19 on the mental health of healthcare workers: Implications for supporting psychological well-being. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lan, F.-Y.; Suharlim, C.; Kales, S.N.; Yang, J. Association between SARS-CoV-2 infection, exposure risk and mental health among a cohort of essential retail workers in the USA. Occup. Environ. Med. 2020, 78, 237–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Rey, R.; Garrido-Hernansaiz, H.; Bueno-Guerra, N. Working in the Times of COVID-19. Psychological Impact of the Pandemic in Frontline Workers in Spain. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 18149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mental Health Research Canada. COVID Data Portal-MHRC. 2020. Available online: https://www.mhrc.ca/covid-data-portal (accessed on 23 August 2021).

- De Boni, R.B.; Balanzá-Martínez, V.; Mota, J.C.; Cardoso, T.D.A.; Ballester, P.; Atienza-Carbonell, B.; Bastos, F.I.; Kapczinski, F. Depression, Anxiety, and Lifestyle among Essential Workers: A Web Survey from Brazil and Spain during the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e22835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabah, A.; Ramanan, M.; Laupland, K.B.; Buetti, N.; Cortegiani, A.; Mellinghoff, J.; Conway Morris, A.; Camporota, L.; Zappella, N.; Elhadi, M.; et al. Personal protective equipment and intensive care unit healthcare worker safety in the COVID-19 era (PPE-SAFE): An international survey. J. Crit. Care 2020, 59, 70–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boovaragasamy, C.; Kumar, M.; Sandirakumaran, A.; Gnanasabai, G.; Rahman, M.; Govindasamy, A. COVID-19 and police personnel: An exploratory community based study from South India. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2021, 10, 816–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeung, N.C.Y.; Huang, B.; Lau, C.Y.K.; Lau, J.T.F. Feeling Anxious amid the COVID-19 Pandemic: Psychosocial Correlates of Anxiety Symptoms among Filipina Domestic Helpers in Hong Kong. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 18102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Hage, W.; Hingray, C.; Lemogne, C.; Yrondi, A.; Brunault, P.; Bienvenu, T.; Etain, B.; Paquet, C.; Gohier, B.; Bennabi, D.; et al. Health professionals facing the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic: What are the mental health risks? Enceph.-Rev. Psychiatr. Clin. Biol. Ther. 2020, 46, S73–S80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgantini, L.A.; Naha, U.; Wang, H.; Francavilla, S.; Acar, Ö.; Flores, J.M.; Crivellaro, S.; Moreira, D.; Abern, M.; Eklund, M.; et al. Factors contributing to healthcare professional burnout during the COVID-19 pandemic: A rapid turnaround global survey. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0238217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barello, S.; Palamenghi, L.; Graffigna, G. Burnout and somatic symptoms among frontline healthcare professionals at the peak of the Italian COVID-19 pandemic. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 290, 113129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preti, E.; Di Mattei, V.; Perego, G.; Ferrari, F.; Mazzetti, M.; Taranto, P.; Di Pierro, R.; Madeddu, F.; Calati, R. The Psychological Impact of Epidemic and Pandemic Outbreaks on Healthcare Workers: Rapid Review of the Evidence. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2020, 22, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.-S.; Lee, E.-H.; Park, N.-R.; Choi, Y.H. Mental Health of Nurses Working at a Government-designated Hospital during a MERS-CoV Outbreak: A Cross-sectional Study. Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2017, 32, 2–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Elovainio, M.; Kivimäki, M.; Steen, N.; Kalliomäki-Levanto, T. Organizational and individual factors affecting mental health and job satisfaction: A multilevel analysis of job control and personality. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2000, 5, 269–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sallie, S.N.; Ritou, V.; Bowden-Jones, H.; Voon, V. Assessing international alcohol consumption patterns during isolation from the COVID-19 pandemic using an online survey: Highlighting negative emotionality mechanisms. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e044276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychological Association (APA). Essential Workers More Likely to be Diagnosed with a Mental Health Disorder during Pandemic. 2020. Available online: https://www.apa.org/news/press/releases/stress/2021/one-year-pandemic-stress-essential (accessed on 23 August 2021).

- Esterwood, E.; Saeed, S.A. Past Epidemics, Natural Disasters, COVID19, and Mental Health: Learning from History as we Deal with the Present and Prepare for the Future. Psychiatr. Q. 2020, 91, 1121–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosemberg, M.-A.S.; Adams, M.; Polick, C.; Li, W.V.; Dang, J.; Tsai, J.H.-C. COVID-19 and mental health of food retail, food service, and hospitality workers. J. Occup. Environ. Hyg. 2021, 18, 169–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coley, R.L.; Baum, C.F. Trends in mental health symptoms, service use, and unmet need for services among U.S. adults through the first 9 months of the COVID-19 pandemic. Transl. Behav. Med. 2021, 11, 1947–1956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mongelli, F.; Georgakopoulos, P.; Pato, M.T. Challenges and Opportunities to Meet the Mental Health Needs of Underserved and Disenfranchised Populations in the United States. Focus 2020, 18, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cairns, P.; Aitken, G.; Pope, L.M.; Cecil, J.E.; Cunningham, K.B.; Ferguson, J.; Smith, K.G.; Gordon, L.; Johnston, P.; Laidlaw, A.; et al. Interventions for the well-being of healthcare workers during a pandemic or other crisis: Scoping review. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e047498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cénat, J.M.; Felix, N.; Blais-Rochette, C.; Rousseau, C.; Bukaka, J.; Derivois, D.; Noorishad, P.-G.; Birangui, J.-P. Prevalence of mental health problems in populations affected by the Ebola virus disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 289, 113033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, J.; Lipsitz, O.; Nasri, F.; Lui, L.M.W.; Gill, H.; Phan, L.; Chen-Li, D.; Iacobucci, M.; Ho, R.; Majeed, A.; et al. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on mental health in the general population: A systematic review. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 277, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toh, W.L.; Meyer, D.; Phillipou, A.; Tan, E.J.; Van Rheenen, T.E.; Neill, E.; Rossell, S.L. Mental health status of healthcare versus other essential workers in Australia amidst the COVID-19 pandemic: Initial results from the collate project. Psychiatry Res. 2021, 298, 113822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munn, Z.; Peters, M.D.J.; Stern, C.; Tufanaru, C.; McArthur, A.; Aromataris, E. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2018, 18, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Peterson, J.; Pearce, P.F.; Ferguson, L.A.; Langford, C.A. Understanding scoping reviews: Definition, purpose, and process. J. Am. Assoc. Nurse Pract. 2017, 29, 12–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Methley, A.M.; Campbell, S.; Chew-Graham, C.; McNally, R.; Cheraghi-Sohi, S. PICO, PICOS and SPIDER: A comparison study of specificity and sensitivity in three search tools for qualitative systematic reviews. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2014, 14, 579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Miller, J.J.; Niu, C.; Moody, S. Child welfare workers and peritraumatic distress: The impact of COVID-19. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2020, 119, 105508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Mayer, G.; Hummel, S.; Oetjen, N.; Gronewold, N.; Zafar, A.; Schultz, J.-H. Mental Health Burden in Different Professions During the Final Stage of the COVID-19 Lockdown in China: Cross-sectional Survey Study. J. Med Internet Res. 2020, 22, e24240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiz-Frutos, C.; Ortega-Moreno, M.; Allande-Cussó, R.; Domínguez-Salas, S.; Dias, A.; Gómez-Salgado, J. Health-related factors of psychological distress during the COVID-19 pandemic among non-health workers in Spain. Saf. Sci. 2020, 133, 104996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiz-Frutos, C.; Ortega-Moreno, M.; Allande-Cussó, R.; Ayuso-Murillo, D.; Domínguez-Salas, S.; Gómez-Salgado, J. Sense of coherence, engagement, and work environment as precursors of psychological distress among non-health workers during the COVID-19 pandemic in Spain. Saf. Sci. 2020, 133, 105033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quandt, S.A.; LaMonto, N.J.; Mora, D.C.; Talton, J.W.; Laurienti, P.J.; Arcury, T.A. COVID-19 Pandemic among Immigrant Latinx Farmworker and Non-farmworker Families: A Rural-Urban Comparison of Economic, Educational, Healthcare, and Immigration Concerns. N. Solut. A J. Environ. Occup. Health Policy 2021, 31, 30–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Camargo, C. “It’s tough shit, basically, that you’re all gonna get it”: UK virus testing and police officer anxieties of contracting COVID-19. Polic. Soc. 2021, 32, 35–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabasakal, E.; Özpulat, F.; Akca, A.; Özcebe, L.H. Mental health status of health sector and community services employees during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 2021, 94, 1249–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lightfoot, E.; Moone, R.; Suleiman, K.; Otis, J.; Yun, H.; Kutzler, C.; Turck, K. Concerns of Family Caregivers during COVID-19: The Concerns of Caregivers and the Surprising Silver Linings. J. Gerontol. Soc. Work 2021, 64, 656–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Yu, H.; Yang, W.; Mo, Q.; Yang, Z.; Wen, S.; Zhao, F.; Zhao, W.; Tang, Y.; Ma, L.; et al. Depression and Anxiety Among Quarantined People, Community Workers, Medical Staff, and General Population in the Early Stage of COVID-19 Epidemic. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 638985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, S.; Roy, A.; Domeracki, S.J.; Mohrmann, T.; Missar, V.; Jule, J.; Sharma, S.; DeWitt, R. The Low-Wage Essential Worker: Occupational Concerns and Needs in the COVID-19 Pandemic-A Round Table. Work. Health Saf. 2021, 69, 154–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Frutos, C.; Ortega-Moreno, M.; Dias, A.; Bernardes, J.M.; García-Iglesias, J.J.; Gómez-Salgado, J. Information on COVID-19 and psychological distress in a sample of non-health workers during the pandemic period. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 96982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Xin, M.; Zhang, C.; Dong, W.; Fang, Y.; Wu, W.; Li, M.; Pang, J.; Zheng, Z.; Wang, Z.; et al. Associations of Mental Health and Personal Preventive Measure Compliance with Exposure to COVID-19 Information during Work Resumption Following the COVID-19 Outbreak in China: Cross-Sectional Survey Study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e22596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, X.; Zhang, J.; Teng, C.; Zhao, K.; Su, K.-P.; Wang, Z.; Tang, W.; Zhang, C. Depressive symptoms in the front-line non-medical workers during the COVID-19 outbreak in Wuhan. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 276, 441–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazaro-Perez, C.; Martinez-Lopez, J.A.; Gomez-Galan, J.; Fernandez-Martinez, M.D. COVID-19 Pandemic and Death Anxiety in Security Forces in Spain. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 17760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zolnikov, T.R.; Furio, F. Stigma on First Responders during COVID-19. Stigma Health 2020, 5, 375–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, F.; Sifat, R.I. The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Mental Health of the Rickshaw-Puller in Bangladesh. J. Loss Trauma 2020, 26, 782–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markovic, I.; Nikolovski, S.; Milojevic, S.; Zivkovic, D.; Knezevic, S.; Mitrovic, A.; Fiser, Z.; Djurdjevic, D. Public trust and media influence on anxiety and depression levels among skilled workers during the COVID-19 outbreak in Serbia. Vojn. Pregl. 2020, 77, 1201–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, Y.M.; Wu, K.S.; Lin, K.L.; Xu, D. Mental health impact of COVID-19 on quarantine hotel employees in China. Risk Manag. Healthc. Policy 2020, 13, 2743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Li, H. Self-Rated Physical and Mental Health of Community Workers during the Covid-19 Outbreak in China: A Cross-Sectional Study. Acta Med. Mediterr. 2020, 36, 3711–3717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todorovic, N.; Vracevic, M.; Rajovic, N.; Pavlovic, V.; Madzarevic, P.; Cumic, J.; Mostic, T.; Milic, N.; Rajovic, T.; Sapic, R.; et al. Quality of Life of Informal Caregivers behind the Scene of the COVID-19 Epidemic in Serbia. Medicina 2020, 56, 647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco-Donoso, L.M.; Moreno-Jiménez, J.; Amutio, A.; Gallego-Alberto, L.; Moreno-Jiménez, B.; Garrosa, E. Stressors, job resources, fear of contagion, and secondary traumatic stress among nursing home workers in face of the COVID-19: The case of Spain. J. Appl. Gerontol. 2021, 40, 244–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-López, A.M.; Rubio-Valdehita, S.; Díaz-Ramiro, E.M. Influence of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental workload and burnout of fashion retailing workers in spain. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 30983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, E. An outbreak of fear, rumours and stigma: Psychosocial support for the Ebola virus disease outbreak in West Africa. Intervention 2015, 1, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Frenkel, M.O.; Giessing, L.; Egger-Lampl, S.; Hutter, V.; Oudejans, R.R.; Kleygrewe, L.; Jaspaert, E.; Plessner, H. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on European police officers: Stress, demands, and coping resources. J. Crim. Justice 2021, 72, 101756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, C.; Williman, J.; Beaglehole, B.; Stanley, J.; Jenkins, M.; Gendall, P.; Rapsey, C.; Every-Palmer, S. Challenges facing essential workers: A cross-sectional survey of the subjective mental health and well-being of New Zealand healthcare and ‘other’essential workers during the COVID-19 lockdown. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e048107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.; Zhao, N. Generalized anxiety disorder, depressive symptoms and sleep quality during COVID-19 outbreak in China: A web-based cross-sectional survey. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 288, 112954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bender, A.E.; Berg, K.A.; Miller, E.K.; Evans, K.E.; Holmes, M.R. “Making Sure We Are All Okay”: Healthcare Workers’ Strategies for Emotional Connectedness during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Clin. Soc. Work J. 2021, 49, 445–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blake, H.; Bermingham, F.; Johnson, G.; Tabner, A. Mitigating the Psychological Impact of COVID-19 on Healthcare Workers: A Digital Learning Package. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 92997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sritharan, J.; Jegathesan, T.; Vimaleswaran, D.; Sritharan, A. Mental Health Concerns of Frontline Workers during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Scoping Review. Glob. J. Health Sci. 2020, 12, 89–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, N.; Wei, L.; Shi, S.; Jiao, D.; Song, R.; Ma, L.; Wang, H.; Wang, C.; Wang, Z.; You, Y.; et al. A qualitative study on the psychological experience of caregivers of COVID-19 patients. Am. J. Infect. Control 2020, 48, 592–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Que, J.; Shi, L.; Deng, J.; Liu, J.; Zhang, L.; Wu, S.; Gong, Y.; Huang, W.; Yuan, K.; Yan, W.; et al. Psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on healthcare workers: A cross-sectional study in China. Gen. Psychiatry 2020, 33, e100259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goel, N.; Workman, J.L.; Lee, T.T.; Innala, L.; Viau, V. Sex differences in the HPA axis. Compr. Physiol. 2014, 4, 1121–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carek, P.J.; Laibstain, S.E.; Carek, S.M. Exercise for the treatment of depression and anxiety. Int. J. Psychiatry Med. 2011, 41, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Migliorini, C.; Lam, D.; Harvey, C. Supporting family and friends of young people with mental health issues using online technology: A rapid scoping literature review. Early Interv. Psychiatry 2021, 2021, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gold, J.A. COVID-19: Adverse mental health outcomes for healthcare workers. BMJ—Br. Med. J. 2020, 369, m1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Capasso, A.; Jones, A.M.; Ali, S.H.; Foreman, J.; Tozan, Y.; DiClemente, R.J. Increased alcohol use during the COVID-19 pandemic: The effect of mental health and age in a cross-sectional sample of social media users in the U.S. Prev. Med. 2021, 145, 106422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ornell, F.; Moura, H.F.; Scherer, J.N.; Pechansky, F.; Kessler, F.H.P.; von Diemen, L. The COVID-19 pandemic and its impact on substance use: Implications for prevention and treatment. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 289, 113096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafer, K.C. Trauma and the Substance-Abusing Older Adult: Innovative Questions for Accurate Assessment. J. Loss Trauma 2004, 9, 345–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

|

Searched using (All ‘A’ terms) AND (All ‘B’ terms) AND (All ‘C’ terms) |

| Academic Databases | Grey Databases |

|---|---|

| MEDLINE PsycInfo CINAHL Sociological Abstracts Web of Science | Google Scholar |

| Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria | |

|---|---|---|

| Population | Essential workers | Health-related essential workers |

| Intervention/issue | Any mental-health-related issues and intervention, including depression, anxiety, stress, sleep quality, etc. | Not applicable |

| Comparison | Not applicable | Not applicable |

| Outcome | Participant-reported mental health issues, factors associated with those issues, and coping strategies adopted by the participants or supports provided | Any outcome not originating from mental health issues due to COVID-19, such as mental health issues related to certain stressful jobs regardless of COVID-19 (e.g., police and firefighters) |

| Study type | Primary research including observational and experimental studies, qualitative studies, field report, and case studies | Not applicable |

| Study | Study Objective | Study Type | Data Collection | Time of the Study | Location of the Study | Population Size (n) | Age (y as Mean or Range) | Study Population | Outbreak Name | Mental Health Issue |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Miller et al. (2020) [34] | To explore whether COVID-19 caused the child welfare worker any peritraumatic distress | Quantitative | Online survey | Summer of 2020 | USA | 1996 | 41.44 | Male 188, female 1804, other 4; 800 employed by a private child welfare agency; 1196 employed by a public child welfare agency | COVID-19 | Peritraumatic distress; overall child welfare workers fall under the mild distress category |

| Du et al. (2020) [35] | To evaluate the burden of mental health issues on several professions in China to identify vulnerable groups, factors influencing the issue, and better coping mechanisms | Quantitative | Online survey | March to April 2020 | China | 687 | 36.92 | 158 doctors, 221 nurses, 24 other medical staff, 43 students, 60 teachers/government staff, 135 economy staff, 26 workers/farmers, and 20 professions designated under the “other” category | COVID-19 | Depression, anxiety, and stress |

| Ruiz-Frutos et al. (2021) [36] | To study the differences between the mental health of non-health workers who work from home and those who work away from home (essential non-health workers) | Quantitative | Survey | March to April 2020 | Spain | 1089 workers; 494 away from home, 597 from home | 42.1 | Currently active worker; adult | COVID-19 | Psychological distress |

| Ruiz-Frutos et al. (2021) [37] | To assess the effects of COVID-19 on the physical and mental health of non-health workers | Quantitative | Survey | March to April 2020 | Spain | 1089 workers; 494 away from home, 597 from home | 42.1 | Currently active worker; adult | COVID-19 | Psychological distress |

| Boovaragasamy et al. (2021) [12] | To explore the perception of police personnel towards COVID-19 and the factors influencing their stress and coping abilities amid COVID-19 | Qualitative | Interviews | April of 2020 | India | 32 | 25–60 | Police personnel; 78.12% were married, 62.5% were in the profession for over 5 years | COVID-19 | Stress |

| Quandt et al. (2021) [38] | To explore the experience of women in families during COVID-19 in work and household economics, childcare and education, health care, and the community social climate concerning discrimination and racism | Quantitative | Survey | May to June 2020 | USA | 105 | 25–47 | Female Latinx farmworkers and female non-farmworkers | COVID-19 | Stress, worry about contracting COVID-19, worry about children |

| De Camargo (2021) [39] | To explore the fears and anxiety of contracting COVID-19 in police officers | Qualitative | Online interviews | May to June 2020 | United Kingdom | 18 | 22–54 | 88.8% were married or in a relationship, average experience of 10 years | COVID-19 | Stress, the safety of family and others |

| Kabasakal et al. (2021) [40] | To evaluate the depression, anxiety, and stress status of health sector and community service workers who were actively working during the pandemic | Quantitative | Survey | May to June 2020 | Turkey | 735 | 45 years and older | Health and service sector employees | COVID-19 | Depression, anxiety, and stress |

| Lightfoot et al. (2021) [41] | To explore the concerns and benefits of family caregivers during the COVID-19 pandemic | Qualitative | Interviews | May and September 2020 | Minnesota, USA | 52 | 58 | Family caregivers | COVID-19 | Concerns about the mental and physical health of elderly family members, keeping them safe from COVID-19 |

| Li et al. (2021) [42] | To determine the prevalence of anxiety and depression related to the COVID-19 pandemic in quarantined people, community workstation staff-policemen-volunteers (CPV) and the general public, and to examine their potential risk factors | Quantitative | Survey | March 2020 | Hubei, China | 3303 | 18 years and above | General medical staff, the general public, front-line health care workers, community workstation staff-policemen-volunteers (CPV) and quarantined people | COVID-19 | Anxiety, depression |

| Gallagher et al. (2021) [43] | To explore the concerns and needs of low-wage essential workers as understood by experts in the field | Qualitative | Roundtable discussion | N/R | USA | Risk manager/analysts, a professional health educator/trainer, senior leaders, and occupational health professionals were invited to participate; representatives from the dairy, childcare, food bank, and healthcare industries were included | COVID-19 | Non-specific mental health | ||

| Lan et al. (2021) [7] | To investigate SARS-CoV-2 infection and exposure risks among grocery retail workers, and to investigate their mental health state during the pandemic | Quantitative | Survey | May 2020 | Massachusetts, USA | 104 | 18 and above | Grocery retail store employees | COVID-19 | Anxiety and depression |

| Toh et al. (2021) [29] | To characterize the concerns endorsed by health care workers and other essential workers relative to the general population and to explore differences among these groups | Quantitative | Survey | April 2020 to March 2021 | Australia | 5158 | 18 and above | Essential workers, non-essential workers, and the general population | COVID-19 | Depression, anxiety, and stress |

| Ruiz-Frutos et al. (2020) [44] | To explore what influenced the level of psychological distress in a sample of non-health workers in Spain | Qualitative | Survey | March to April 2020 | Spain | 1089 | 18 and above | Non-health workers | COVID-19 | Psychological distress |

| Pan et al. (2020) [45] | To investigate the associations between COVID-19-specific information exposure and four outcome variables, including depression, sleep quality, self-reported consistent face-mask-wearing, and hand hygiene | Qualitative | Survey | March 2020 | Shenzhen, China | 3035 | 18 and above | Factory workers | COVID-19 | Depression, sleep quality |

| De Boni et al. (2020) [10] | To assess the prevalence and predictors of depression, anxiety, and their comorbidity among essential workers in Brazil and Spain during the COVID-19 pandemic | Quantitative | Survey | April to May 2020 | Brazil and Spain | 3745 | Adults | Essential workers | COVID-19 | Depression, anxiety |

| Fang et al. (2020) [46] | To explore mental health outcomes in non-medical volunteers who worked in Wuhan fighting COVID-19, especially to understand the psychological status of volunteers born after the 1990s | Quantitative | Survey | February to March 2020 | Wuhan, China | 191 | >20 years | Non-medical workers | COVID-19 | Positive and negative affect, perception of stress, depression, and emotional state |

| Yeung et al. (2020) [13] | To examine the psychosocial correlates of probable anxiety among Filipina domestic helpers in Hong Kong amid the COVID-19 pandemic | Quantitative | Survey | May 2020 | Hong Kong | 295 | Filipina domestic workers | COVID-19 | Anxiety, COVID-19- specific worries, social support | |

| Rodriguez-Rey et al. (2020) [8] | To explore the psychological symptomatic response of frontline workers working during the COVID-19 pandemic and the potential demographic and work-related factors that may be associated with their symptoms | Quantitative | Online survey | March to June 2020 | Spain | 546 | Healthcare workers | COVID-19 | Psychological impact, depression, degree of concern | |

| Lazaro-Perez et al. (2020) [47] | To understand the level of anxiety in the face of death in essential professionals and to determine the predictive variables involved in this phenomenon | Quantitative | Survey | August to September 2020 | Spain | 2079 | Up to 30 years old, 31–40 years old, 41–50 years old, 51–60 years old, and over 60 years old | Military personnel of the Armed Forces, National Police and Civil Guards | COVID-19 | Death, anxiety, fear of one’s death, fear of the process of dying, fear of death of others, fear of the process of others dying |

| Zolnikov et al. (2020) [48] | To understand stigma experienced by first responders during the COVID-19 pandemic and the consequences of stigma on first responders’ mental health | Qualitative | Interviews | N/R | USA, Kenya, Ireland, Canada | 31 | above 18 | Healthcare workers and first responders | COVID-19 | Depression, anxiety, feeling isolated, stress, insomnia, decreased self-esteem |

| Ahmed and Sifat (2020) [49] | To understand the social, economic, and mental health effects on the lives of deprived and marginalized rickshaw pullers in Bangladesh during the COVID-19 situation | Qualitative | Interviews | N/R | Bangladesh | 11 | 18 or above | Informal workers | COVID-19 | Anxiety, stress, depression |

| Markovic et al. (2020) [50] | To assess the prevalence and degree of anxiety and depression in education, army, and healthcare professionals | Quantitative | Online survey | July 2020 | Serbia | 110 | Not specified | Skilled workers | COVID-19 | Depression, anxiety |

| Teng et al. (2020) [51] | To explore COVID-19-related depression, anxiety, and stress among quarantined hotel employees in China | Quantitative | Online survey | May to June 2020 | China | 170 | Not specified | Quarantined hotel employees | COVID-19 | Depression, anxiety, and stress |

| Zhang et al. (2020) [52] | To describe the physical and mental health of community workers and explore the associated factors | Quantitative | Online survey | February to March 2020 | China | 702 | 18 years or older | Community workers | COVID-19 | Stress, emotional effects, and mental health |

| Rosemberg et al. (2021) [23] | To explore the perspective of workers regarding the effect of COVID-19 on their mental health and coping, including screening for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and alcohol use disorder symptoms | Qualitative | Interviews | N/R | USA | 27 | 18 or older (mean 37 years) | Adult, English-speaking, food retail, food service, or hospitality industry workers, residing in one of the selected 10 states based on COVID-19 case counts per 100,000 population | COVID-19 | Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and alcohol use disorder symptoms |

| Todorovic et al. (2020) [53] | To assess the quality of life of informal caregivers during the COVID-19 epidemic in Serbia | Mixed | Survey, focus groups (via Zoom), interviews (telephone) | March to May 2020 | Serbia | 112 | 51.1 ± 12.3 | Informal caregivers | COVID-19 | Non-specific mental health |

| Blanco-Donoso et al. (2021) [54] | To analyze the psychological consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic on nursing home workers and the influence of certain related stressors and job resources to support the stress | Quantitative | Online survey | N/R | Spain | 228 | 36.29 | Spanish nursing home workers | COVID-19 | Traumatic stress |

| Rodriguez-Lopez et al. (2021) [55] | To analyze the levels of mental workload and the presence of burnout on a sample of fashion retail workers from Spain and its relationship to the COVID-19 pandemic | Quantitative | Online survey | October and November 2020 | Spain | 360 | 32.48 | Spanish fashion retail workers | COVID-19 | Mental workload and burnout |

| Cheung (2015) [56] | To summarize the experience and lessons learned from the Ebola virus disease outbreak in Liberia | Qualitative | Field report | N/R | Liberia | NA | NA | NA | Ebola | Fear, rumours, and stigma |

| Frenkel et al. (2020) [57] | To determine whether facing the COVID-19 pandemic affects police officers as they are confronted with various novel challenges | Mixed | Online survey with free response feature | March to June 2020 | Global (Austria, Germany, Switzerland, the Netherlands, and Spain) | 2567 | 39.69 | European police officers | COVID-19 | Strain |

| Bell et al. (2021) [58] | To compare psychological outcomes, experiences, and sources of stress over the COVID-19 lockdown in New Zealand in essential workers (healthcare and “other” essential workers) with that of workers in non-essential work roles | Quantitative | Online survey | April to May 2020 | New Zealand | 2495 | 18 or over | Healthcare and other essential workers | COVID-19 | Anxiety, distress, well-being |

| Mental Health Issues | Scales/Instruments Used |

|---|---|

| Anxiety |

|

| Depression |

|

| Stress and distress |

|

| Fear and worries |

|

| Mood and emotional effects |

|

| General mental health and quality of life |

|

| Sleep and burnout |

|

| Others |

|

| Categories | Occupations (Non-Health Essential Workers) | Study | Main Findings per Study | Factors per Study | Coping Mechanisms |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factory and production occupations | Factory workers | Pan et al. (2020) [45] |

|

| N/R |

| Electronic device manufacturing | |||||

| Watchmaking | |||||

| Beverage manufacturing | |||||

| Biotechnology product manufacturing | |||||

| Biopharmaceutical-related industry workers | Fang et al. (2020) [46] |

|

| N/R | |

| Farming, fishing, agriculture, and forestry occupations | Farmers | Fang et al. (2020) [46] |

|

| N/R |

| Quandt et al. (2021) [38] |

|

| N/R | ||

| Du et al. (2020) [35] |

|

|

| ||

| Food preparation and serving occupations | Butchers | Kabasakal et al. (2021) [40] |

|

|

|

| Bakers | |||||

| Drinking-water dealers | |||||

| Food services | |||||

| Catering sector workers | |||||

| Food and dairy | Gallagher et al. (2021) [43] |

|

|

| |

| Meatpacking industry | |||||

| Restaurants | |||||

| Hospitality workers | Rosemberg et al. (2021) [23] |

|

|

| |

| Food retail | |||||

| Food | De Boni et al. (2020) [10] |

|

| N/R | |

| Hotel employees | Teng et al. (2020) [51] |

|

|

| |

| Installation, maintenance, cleaning, and repair workers | Cleaning | De Boni et al. (2020) [10] |

|

| N/R |

| Domestic workers/helpers | Yeung et al. (2020) [13] |

|

|

| |

| Landscape workers | Gallagher et al. (2021) [43] |

|

| N/R | |

| Housekeeping workers | |||||

| Police officers | Frenkel et al. (2020) [57] |

|

|

| |

| De Camargo (2021) [39] |

|

| N/R | ||

| Boovaragasamy et al. (2021) [12] |

|

|

| ||

| Firefighters | Toh et al. (2021) [29] |

|

| N/R | |

| Protective service workers | Rodriguez-Rey et al. (2020) [8] |

|

|

| |

| Military personnel | Markovic et al. (2020) [50] |

|

| N/R | |

| Civil guards | Lazaro-Perez et al. (2020) [47] |

|

| N/R | |

| Police officers | Zolnikov et al. (2020) [48] |

|

| N/R | |

| Sales and related occupations | Grocery retail workers | Lan et al. (2021) [7] |

|

|

|

| Rodriguez-Rey et al. (2020) [8] |

|

| N/R | ||

| Rosemberg et al. (2021) [23] |

|

| N/R | ||

| Cashiers | Kabasakal et al. (2021) [40] |

|

| N/R | |

| Booth attendants | |||||

| Supermarket workers | Toh et al. (2021) [29] |

|

| N/R | |

| Fashion retailing workers |

|

| N/R | ||

| Social care practice and support | Child care/welfare workers | Miller et al. (2020) [34] |

|

|

|

| Community workstation staff-policemen-volunteers | Li et al. (2021) [42] |

|

| N/R | |

| Community/social workers | Zhang et al. (2020) [52] |

|

| N/R | |

| Informal caregivers | Lightfoot et al. (2021) [41] |

|

| N/R | |

| Todorovic et al. (2020) [53] |

|

| N/R | ||

| Geriatric assistants | Blanco-Donoso et al. (2021) [54] |

|

| N/R | |

| Nursing home managers | N/R | ||||

| Aid workers | Cheung (2015) [56] |

|

|

| |

| Logistics and cargo services workers | Toh et al. (2021) [29] |

|

| N/R | |

| Transportation workers | De Boni et al. (2020) [10] |

|

| N/R | |

| Rickshaw pullers | Ahmed and Sifat (2020) [49] |

|

| N/R | |

| Other | Media professionals | Rodriguez-Rey et al. (2020) [8] |

|

| N/R |

| Non-specific health care essential workers | Ruiz-Frutos et al. (2021) [37] |

|

| N/R | |

| Ruiz-Frutos et al. (2021) [36] |

|

| N/R | ||

| Ruiz-Frutos et al. (2020) [44] |

|

| N/R | ||

| Bell et al. (2021) [58] |

|

|

|

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chowdhury, N.; Kainth, A.; Godlu, A.; Farinas, H.A.; Sikdar, S.; Turin, T.C. Mental Health and Well-Being Needs among Non-Health Essential Workers during Recent Epidemics and Pandemics. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 5961. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19105961

Chowdhury N, Kainth A, Godlu A, Farinas HA, Sikdar S, Turin TC. Mental Health and Well-Being Needs among Non-Health Essential Workers during Recent Epidemics and Pandemics. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(10):5961. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19105961

Chicago/Turabian StyleChowdhury, Nashit, Ankit Kainth, Atobrhan Godlu, Honey Abigail Farinas, Saif Sikdar, and Tanvir C. Turin. 2022. "Mental Health and Well-Being Needs among Non-Health Essential Workers during Recent Epidemics and Pandemics" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 10: 5961. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19105961

APA StyleChowdhury, N., Kainth, A., Godlu, A., Farinas, H. A., Sikdar, S., & Turin, T. C. (2022). Mental Health and Well-Being Needs among Non-Health Essential Workers during Recent Epidemics and Pandemics. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(10), 5961. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19105961