Costs of Employee Stewardship Behaviors for Employees in the Work-to-Family Penetration Context during the COVID-19 Pandemic

Abstract

:1. Introduction

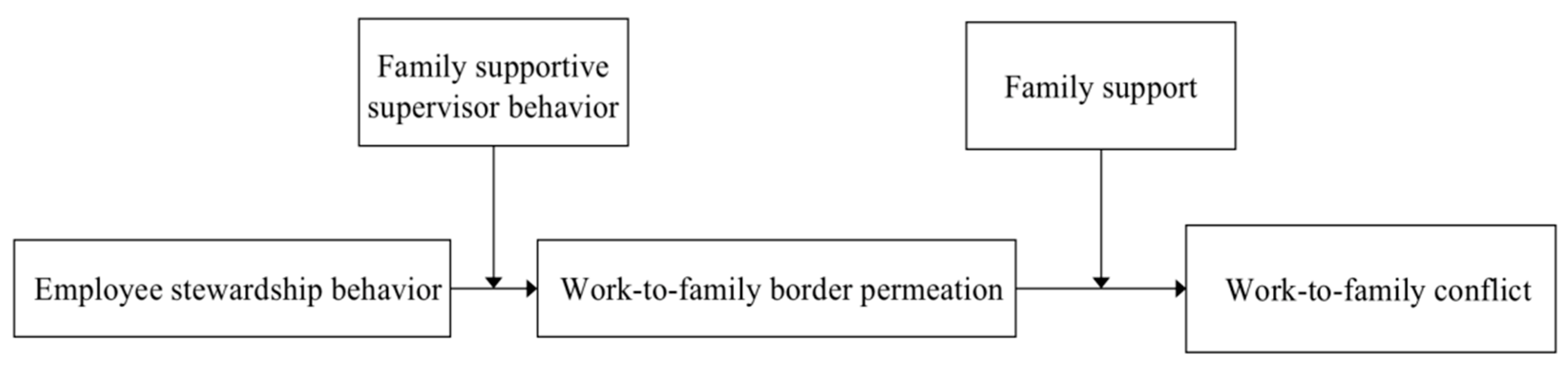

2. Theoretical Background and Hypotheses

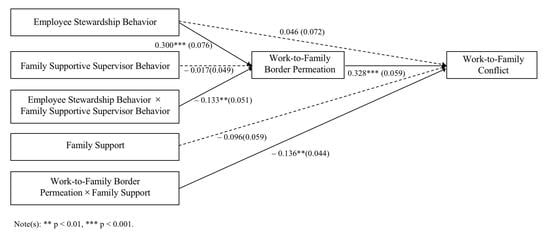

2.1. ESB and WFC

2.2. Mediating Role of Work–Family Boundary Permeation

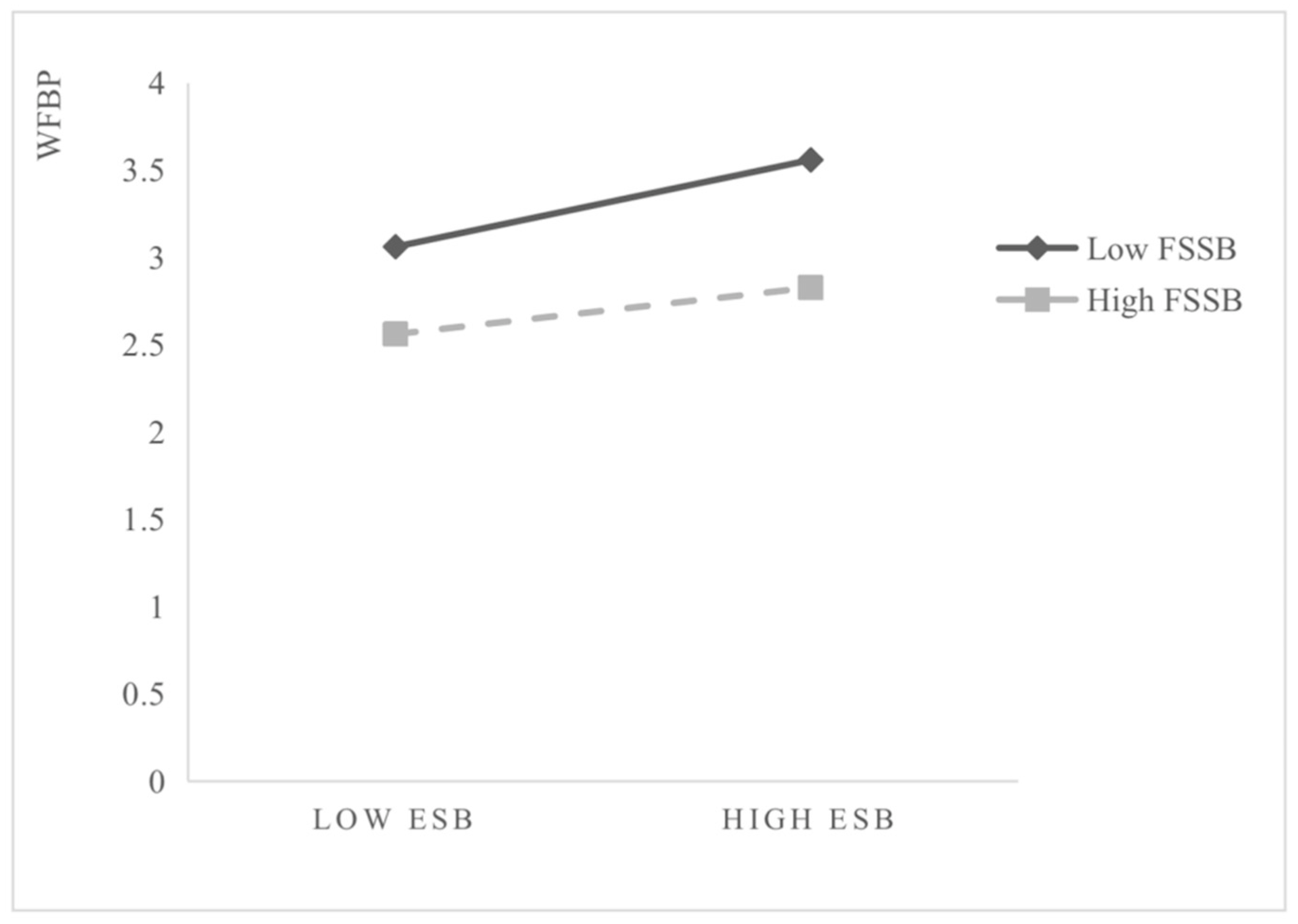

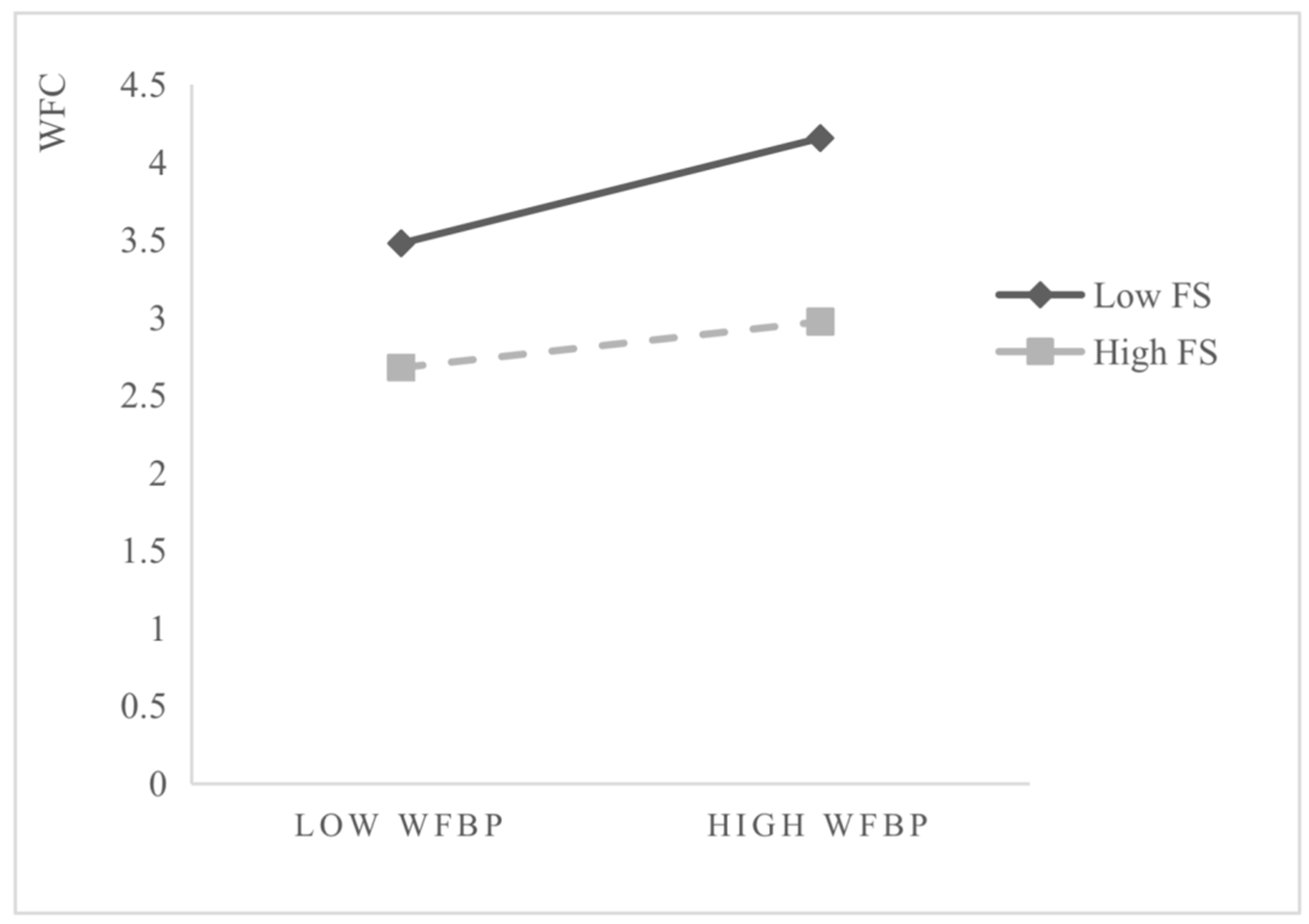

2.3. Moderating Role of a Family-Supportive Supervisor and Family Support

3. Methods

3.1. Procedure and Participants

3.2. Ethical Considerations

3.3. Measures

4. Results

4.1. Preliminary Analyses

4.2. Hypotheses Testing

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Practical Implications

5.3. Limitations and Future Directions

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hernandez, M. Toward an understanding of the psychology of stewardship. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2012, 37, 172–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, J.H.; Schoorman, F.D.; Donaldson, L. Davis, Schoorman, and Donaldson reply: The distinctiveness of agency theory and stewardship theory. Acad. Manag. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1997, 22, 611. [Google Scholar]

- Aßländer, M.S.; Roloff, J.; Nayır, D.Z. Suppliers as stewards? Managing social standards in first-and second-tier suppliers. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 139, 661–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Breton-Miller, I.; Miller, D. Learning stewardship in family firms: For family, by family, across the life cycle. Acad. Manag. Learn. Educ. 2015, 14, 386–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henssen, B.; Koiranen, M. CEOs’ Joy of Working for the Family Firm: The Role of Psychological Ownership and Stewardship Behavior. Entrep. Res. J. 2021, 11, 191–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G.; Hofstede, G.J.; Minkov, M. Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind; Mcgraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Kuppelwieser, V.G. Stewardship Behavior and Creativity. Manag. Revu 2011, 22, 274–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Le Breton-Miller, I.; Miller, D.; Lester, R.H. Stewardship or agency? A social embeddedness reconciliation of conduct and performance in public family businesses. Organ. Sci. 2011, 22, 704–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashwin, A.S.; Krishnan, R.T.; George, R. Family firms in India: Family involvement, innovation and agency and stewardship behaviors. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2015, 32, 869–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Chen, C.C.; Li, X.; Zhou, Y. From personal relationship to psychological ownership: The importance of manager–owner relationship closeness in family businesses. Manag. Organ. Rev. 2013, 9, 295–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, J.; Frankforter, S.; Vollrath, D.; Hill, V. An Empirical Test of Stewardship Theory. J. Bus. Leadersh. Res. Pract. Teach. 2007, 3, 40–50. [Google Scholar]

- Kramer, A.; Kramer, K.Z. The potential impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on occupational status, work from home, and occupational mobility. J. Vocat. Behav. 2020, 119, 103442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kniffin, K.M.; Narayanan, J.; Anseel, F.; Antonakis, J.; Ashford, S.P.; Bakker, A.B.; Bamberger, P.; Bapuji, H.; Bhave, D.P.; Choi, V.K.; et al. COVID-19 and the workplace: Implications, issues, and insights for future research and action. Am. Psychol. 2021, 76, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spurk, D.; Straub, C. Flexible employment relationships and careers in times of the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Vocat. Behav. 2020, 119, 103435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rofcanin, Y.; Anand, S. Human relations virtual special issue: Flexible work practices and work-family domain. Hum. Relat. 2020, 73, 1182–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, T.D.; Golden, T.D.; Shockley, K.M. How effective is telecommuting? Assessing the status of our scientific findings. Psychol. Sci. Public Interest 2015, 16, 40–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brynjolfsson, E.; Horton, J.J.; Ozimek, A.; Rock, D.; Sharma, G.; TuYe, H.Y. COVID-19 and remote work: An early look at US data (No. w27344). Natl. Bur. Econ. Res. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Gao, J. Does telework stress employees out? A study on working at home and subjective well-being for wage/salary workers. J. Happiness Stud. 2020, 21, 2649–2668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Collins, C.; Landivar, L.C.; Ruppanner, L.; Scarborough, W.J. COVID-19 and the gender gap in work hours. Gend. Work. Organ. 2021, 28, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leroy, S.; Schmidt, A.M.; Madjar, N. Working from home during COVID-19: A study of the interruption landscape. J. Appl. Psychol. 2021, 106, 1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carnevale, J.B.; Hatak, I. Employee adjustment and well-being in the era of COVID-19: Implications for human resource management. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 116, 183–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galanti, T.; Guidetti, G.; Mazzei, E.; Zappalà, S.; Toscano, F. Work from home during the COVID-19 outbreak: The impact on employees’ remote work productivity, engagement, and stress. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2021, 63, 426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ten Brummelhuis, L.L.; Bakker, A.B. A resource perspective on the work–home interface: The work–home resources model. Am. Psychol. 2012, 67, 545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hobfoll, S.E.; Halbesleben, J.; Neveu, J.P.; Westman, M. Conservation of resources in the organizational context: The reality of resources and their consequences. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2018, 5, 103–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Powell, G.N.; Greenhaus, J.H.; Allen, T.D.; Johnson, R.E. Advancing and expanding work-life theory from multiple perspectives. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2019, 44, 54–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, T.D. Family-supportive work environments: The role of organizational perceptions. J. Vocat. Behav. 2001, 58, 414–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kossek, E.E.; Lewis, S.; Hammer, L.B. Work—Life initiatives and organizational change: Overcoming mixed messages to move from the margin to the mainstream. Hum. Relat. 2010, 63, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rothbard, N.P.; Phillips, K.W.; Dumas, T.L. Managing multiple roles: Work-family policies and individuals’ desires for segmentation. Organ. Sci. 2005, 16, 243–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Matthews, R.A.; Barnes-Farrell, J.L.; Bulger, C.A. Advancing measurement of work and family domain boundary characteristics. J. Vocat. Behav. 2010, 77, 447–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammer, L.B.; Ernst Kossek, E.; Bodner, T.; Crain, T. Measurement development and validation of the Family Supportive Supervisor Behavior Short-Form (FSSB-SF). J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2013, 18, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Amstad, F.T.; Meier, L.L.; Fasel, U.; Elfering, A.; Semmer, N.K. A meta-analysis of work–family conflict and various outcomes with a special emphasis on cross-domain versus matching-domain relations. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2011, 16, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Davis, J.H.; Allen, M.R.; Hayes, H.D. Is blood thicker than water? A study of stewardship perceptions in family business. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2010, 34, 1093–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, M.A.; Hamilton, R.T. Ownership and diversification: Agency theory or stewardship theory. J. Manag. Stud. 1994, 31, 69–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhaus, J.H.; Beutell, N.J. Sources of conflict between work and family roles. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1985, 10, 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesmer-Magnus, J.R.; Viswesvaran, C. Convergence between measures of work-to-family and family-to-work conflict: A meta-analytic examination. J. Vocat. Behav. 2005, 67, 215–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenbrunsel, A.E.; Brett, J.M.; Maoz, E.; Stroh, L.K.; Reilly, A.H. Dynamic and static work-family relationships. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Processes 1995, 63, 233–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, J.R.; Rothbard, N.P. Mechanisms linking work and family: Clarifying the relationship between work and family constructs. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2000, 25, 178–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Clark, S.C. Work/family border theory: A new theory of work/family balance. Hum. Relat. 2000, 53, 747–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kossek, E.E.; Lautsch, B.A. Work–family boundary management styles in organizations: A cross-level model. Organ. Psychol. Rev. 2012, 2, 152–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hecht, T.D.; Allen, N.J. A longitudinal examination of the work–nonwork boundary strength construct. J. Organ. Behav. Int. J. Ind. Occup. Organ. Psychol. Behav. 2009, 30, 839–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, D.; Le Breton-Miller, I.; Scholnick, B. Stewardship vs. stagnation: An empirical comparison of small family and non-family businesses. J. Manag. Stud. 2008, 45, 51–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashforth, B.E.; Kreiner, G.E.; Fugate, M. All in a day’s work: Boundaries and micro role transitions. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2000, 25, 472–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voydanoff, P. Social integration, work-family conflict and facilitation, and job and marital quality. J. Marriage Fam. 2005, 67, 666–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson-Buchanan, J.B.; Boswell, W.R. Blurring boundaries: Correlates of integration and segmentation between work and nonwork. J. Vocat. Behav. 2006, 68, 432–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulger, C.A.; Matthews, R.A.; Hoffman, M.E. Work and personal life boundary management: Boundary strength, work/personal life balance, and the segmentation-integration continuum. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2007, 12, 365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. The job demands-resources model: State of the art. J. Manag. Psychol. 2007, 22, 309–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kossek, E.E.; Pichler, S.; Bodner, T.; Hammer, L.B. Workplace social support and work–family conflict: A meta-analysis clarifying the influence of general and work–family-specific supervisor and organizational support. Pers. Psychol. 2011, 64, 289–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Greenhaus, J.H.; Ziegert, J.C.; Allen, T.D. When family-supportive supervision matters: Relations between multiple sources of support and work–family balance. J. Vocat. Behav. 2012, 80, 266–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, M.; Buonocore, F.; Carmeli, A.; Guo, L. When family supportive supervisors meet employees’ need for caring: Implications for work–family enrichment and thriving. J. Manag. 2018, 44, 1678–1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mills, M.J.; Matthews, R.A.; Henning, J.B.; Woo, V.A. Family-supportive organizations and supervisors: How do they influence employee outcomes and for whom? Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2014, 25, 1763–1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, L.A.; Mattimore, L.K.; King, D.W.; Adams, G.A. Family support inventory for workers: A new measure of perceived social support from family members. J. Organ. Behav. 1995, 16, 235–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Liao, H.; Li, N.; Colbert, A. Playing it safe for my family: Exploring the dual effects of family motivation on employee productivity and creativity. Acad. Manag. J. 2020, 63, 1923–1950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aryee, S.; Fields, D.; Luk, V. A cross-cultural test of a model of the work-family interface. J. Manag. 1999, 25, 491–511. [Google Scholar]

- Premeaux, S.F.; Adkins, C.L.; Mossholder, K.W. Balancing work and family: A field study of multi-dimensional, multi-role work-family conflict. J. Organ. Behav. Int. J. Ind. Occup. Organ. Psychol. Behav. 2007, 28, 705–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Netemeyer, R.G.; Boles, J.S.; McMurrian, R. Development and validation of work–family conflict and family–work conflict scales. J. Appl. Psychol. 1996, 81, 400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Bentler, P.M. Fit indices in covariance structure modeling: Sensitivity to underparameterized model misspecification. Psychol. Methods 1998, 3, 424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.J.; Selig, J.P. Advantages of Monte Carlo confidence intervals for indirect effects. Commun. Methods Meas. 2012, 6, 77–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Edwards, J.R.; Lambert, L.S. Methods for integrating moderation and mediation: A general analytical framework using moderated path analysis. Psychol. Methods 2007, 12, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bormann, K.C.; Backs, S.; Hoon, C. What makes nonfamily employees act as good stewards? Emotions and the moderating roles of stewardship culture and gender roles in family firms. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2021, 34, 251–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolino, M.C.; Hsiung, H.H.; Harvey, J.; Le Pine, J.A. “Well, I’m tired of tryin’!” Organizational citizenship behavior and citizenship fatigue. J. Appl. Psychol. 2015, 100, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yanzi, W.; Xiuxiu, Z. The Influence of Family Supportive Supervisor Behavior on Employee Stewardship Behavior. Foreign Econ. Manag. 2020, 42, 48–62. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberger, R.; Stinglhamber, F.; Vandenberghe, C.; Sucharski, I.L.; Rhoades, L. Perceived supervisor support: Contributions to perceived organizational support and employee retention. J. Appl. Psychol. 2002, 87, 565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frye, N.K.; Breaugh, J.A. Family-friendly policies, supervisor support, work–family conflict, family–work conflict, and satisfaction: A test of a conceptual model. J. Bus. Psychol. 2004, 19, 197–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Gender | 1.570 | 0.496 | ||||||||||

| 2. Age | 31.460 | 9.581 | 0.023 | |||||||||

| 3.Education | 3.110 | 0.953 | 0.044 | −0.263 ** | ||||||||

| 4.Children | 1.520 | 0.736 | 0.049 | 0.678 ** | −0.349 ** | |||||||

| 5.Tenure | 2.570 | 1.287 | 0.028 | 0.809 ** | −0.241 ** | 0.656 ** | ||||||

| 6.ESB | 4.041 | 0.776 | −0.021 | 0.060 | −0.125 * | 0.116 * | 0.110 * | (0.823) | ||||

| 7.WFBP | 3.829 | 0.830 | 0.018 | 0.104 | 0.088 | 0.026 | 0.147 ** | 0.333 ** | (0.872) | |||

| 8.WFC | 2.971 | 1.002 | −0.074 | −0.012 | 0.033 | −0.047 | −0.014 | 0.173 ** | 0.356 ** | (0.904) | ||

| 9.FSSB | 3.454 | 0.960 | 0.030 | −0.007 | −0.013 | −0.006 | −0.026 | 0.154 ** | 0.042 | −0.280 ** | (0.893) | |

| 10.FS | 3.642 | 0.759 | 0.007 | 0.050 | −0.051 | 0.040 | 0.038 | 0.383 ** | 0.208 ** | 0.022 | 0.104 | (0.903) |

| Model | χ2 | df | χ2/df | CFI | TLI | RMSEA | SRMR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Five-factor model | 565.447 | 340 | 1.633 | 0.954 | 0.948 | 0.045 | 0.044 |

| Four-factor model a | 887.155 | 344 | 2.579 | 0.888 | 0.877 | 0.070 | 0.072 |

| Three-factor model b | 1676.689 | 347 | 4.832 | 0.727 | 0.702 | 0.109 | 0.128 |

| Two-factor model c | 2400.419 | 349 | 6.878 | 0.578 | 0.543 | 0.135 | 0.253 |

| One-factor model | 3481.691 | 350 | 9.948 | 0.356 | 0.305 | 0.166 | 0.184 |

| Variables | Work-to-Family Border Permeation (WFBP) | Work-to-Family Conflict (WFC) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | Model 7 | |

| b | 3.255 *** | 1.707 *** | 2.013 *** | 3.164 *** | 2.162 *** | 1.452 ** | 3.222 *** |

| Gender | 0.019 | 0.031 | 0.027 | −0.148 | −0.14 | −0.153 | −0.122 |

| Age | 0.015 | 0.055 | 0.052 | 0.031 | 0.057 | 0.034 | 0.029 |

| Education | 0.098 | 0.127 ** | 0.117 * | 0.026 | 0.045 | −0.008 | −0.021 |

| Children | −0.102 | −0.133 | −0.137 | −0.085 | −0.105 | −0.05 | −0.025 |

| Tenure | 0.142 * | 0.109 | 0.108 | 0.008 | −0.012 | −0.058 | −0.067 |

| ESB | 0.367 *** | 0.321 *** | 0.238 ** | 0.085 | 0.093 | ||

| FSSB | −0.014 | −0.351 *** | |||||

| ESB × FSSB | −0.149 ** | −0.088 | |||||

| WFBP | 0.416 *** | 0.37 *** | |||||

| FS | −0.106 | ||||||

| WFBP × FS | −0.241 *** | ||||||

| F | 2.764 * | 9.728 *** | 8.678 *** | 0.556 | 2.281 * | 7.43 *** | 11.417 *** |

| R2 | 0.042 | 0.156 | 0.181 | 0.009 | 0.042 | 0.142 | 0.288 |

| Adjust R2 | 0.027 | 0.14 | 0.16 | −0.007 | 0.023 | 0.123 | 0.262 |

| R2 Change | 0.042 | 0.114 | 0.025 | 0.009 | 0.033 | 0.1 | 0.146 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Qian, C.; Gu, X.; Wang, L. Costs of Employee Stewardship Behaviors for Employees in the Work-to-Family Penetration Context during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 6117. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19106117

Qian C, Gu X, Wang L. Costs of Employee Stewardship Behaviors for Employees in the Work-to-Family Penetration Context during the COVID-19 Pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(10):6117. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19106117

Chicago/Turabian StyleQian, Chen, Xinran Gu, and Lei Wang. 2022. "Costs of Employee Stewardship Behaviors for Employees in the Work-to-Family Penetration Context during the COVID-19 Pandemic" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 10: 6117. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19106117

APA StyleQian, C., Gu, X., & Wang, L. (2022). Costs of Employee Stewardship Behaviors for Employees in the Work-to-Family Penetration Context during the COVID-19 Pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(10), 6117. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19106117