A Pilot Survey: Oral Function as One of the Risk Factors for Physical Frailty

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Outcome

2.2.1. Assessment of Risk of FRAILTY

2.2.2. Assessment of Oral Function

2.2.3. Assessment of Motor Function

2.2.4. Assessment of Social Functions

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Statistics Bureau. Portal Site of Official Statistics of Japan. Available online: http://www.e-stat.go.jp/SG1/estat/KistE.do?lid=000001063433 (accessed on 10 March 2022).

- Gill, T.M.; Gahbauer, E.A.; Han, L.; Allore, H.G. Trajectories of disability in the last year of life. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 362, 1173–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shimada, H.; Makizako, H.; Doi, T.; Yoshida, D.; Tsutsumimoto, K.; Anan, Y.; Uemura, K.; Ito, T.; Lee, S.; Park, H.; et al. Combined prevalence of frailty and mild cognitive impairment in a population of elderly Japanese people. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2013, 14, 518–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.S.; Auyeung, T.W.; Leung, J.; Kwok, T.; Woo, J. Transitions in frailty states among community-living older adults and their associated factors. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2014, 15, 281–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trevisan, C.; Veronese, N.; Maggi, S.; Bagio, G.; Toffanelo, E.D.; Zanbon, S.; Sartori, L.; Musacchio, E.; Perissinotto, E.; Crepaldi, G.; et al. Factors Influencing Transitions Between Frailty States in Elderly Adults: The Progetto Veneto Anziani Longitudinal Study. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2017, 65, 179–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, M.J.; Giuliani, C.; Morey, M.C.; Pieper, C.F.; Evenson, K.R.; Mercer, V.; Cohen, H.J.; Visser, M.; Brach, J.S.; Kritchevsky, S.B.; et al. Physical Activity as a Preventative Factor for Frailty: The Health, Aging, and Body Composition Study. J. Gerontol. Biol. 2009, 64, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hubbard, R.E.; Fallah, N.; Searle, S.D.; Mitnitski, A.; Rockwood, K. Impact of exercise in community-dwelling older adults. PLoS ONE 2009, 4, e6174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Alkhamees, A.A.; Alrashed, S.A.; Alzunnaydi, A.A.; Almohimeed, A.S.; Aljohani, M.S. The psyshological impact COVID-19 pandemic on the general population of Saudi Arabia. Compr. Psychiatry 2020, 102, 152192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, F.; Leger, D.; Fressard, L.; Peretti-Watel, P.; Verger, P.; Coconel, G. COVID-19 health crisis and lockdown associated with high level of sleep complaints and hypnotic uptake at the population level. J. Sleep Res. 2021, 30, e13119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinohara, T.; Saida, K.; Tanaka, S.; Murayama, A. Rapid response: Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on frailty in the elderly citizen; corona-frailty. BMJ 2020, 369, m1543. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, B.; Chen, H.; Huangm, L.; Ruan, Y.; Qi, S.; Guo, Y.; Huang, Z.; Sun, S.; Chen, X.; Shi, Y.; et al. Changes in frailty among community-dwelling Chinese older adults and its predictors: Evidence from a two-year longitudinal study. BMC Geriatr. 2020, 20, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kodama, A.; Kume, Y.; Lee, S.; Makizako, H.; Shimada, H.; Takahashi, T.; Ono, T.; Ota, H. Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic Exacerbation of Depressive Symptoms for Social Frailty from the ORANGE Registry. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makizako, H.; Shimada, H.; Tsutsumimoto, K.; Lee, S.; Doi, T.; Nakakubo, S.; Hotta, R.; Suzuki, T. Social Frailty in Community-Dwelling Older Adults as a Risk Factor for Disability. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2015, 16, 1003.e7–1003.e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cudjoe, T.K.; Kotwal, A.A. “Social distancing” amidst a crisis in social isolation and loneliness. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2006, 50, 776–780. [Google Scholar]

- Takeuchi, N.; Sawada, N.; Ekuni, D.; Morita, M. Oral Factors as Predictors of Frailty in Communitiy-Dweling Older People: A Prospective Cohort Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishimoto, M.; Tanaka, T.; Takahashi, K.; Unyapon, S.; Fujisaki, M.S.S.; Yoshizawa, Y.; Iijima, K. Oral frailty is associated with food satisfaction in community-dwelling older adults. Jpn. J. Gerontol. 2020, 57, 273–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, T.; Hirano, H.; Ohara, Y.; Nishimoto, M.; Iijima, K. Oral Frailty Index-8 in the risk assessment of new-onset oral frailty and functional disability among community-dwelling older adults. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2021, 94, 104340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naito, M.; Suzukamo, Y.; Nakayama, T.; Hamajima, N.; Fukuhara, S. Linguistic adaptation and validation of the General Oral Health Assessment Index (GOHAI) in an elderly Japanese population. J. Public Health Dent. 2006, 66, 273–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurimoto, A.; Awata, S.; Ohkubo, T.; Tsubota, M.U.; Asayama, K.; Takahashi, K.; Suenaga, K.; Satoh, H.; Imai, Y. Reliability and validity of the Japanese version of the abbreviated Lubben Social Network Scale. Jpn. J. Gerontol. 2011, 48, 149–157. [Google Scholar]

- Ohkubo, S. Correlates to male participation in disability prevention programs for the elderly. Jpn. J. Public Health 2005, 52, 1050–1058. [Google Scholar]

- Haider, S.; Grabovac, I.; Drgac, D.; Mogg, C.; Oberndorfer, M.; Dorner, T.E. Impact of physical activity, protein intake and social network and their combination on the development of frailty. Eur. J. Public Health 2020, 30, 340–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatanaka, Y.; Furuya, J.; Sato, Y.; Uchida, Y.; Shichita, T.; Kitagawa, N.; Osawa, T. Associations between Oral Hypofunction Tests, Age, and Sex. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 10258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matshuo, K.; Taniguchi, H.; Nakagawa, K.; Kanazawa, M.; Furuya, J.; Tsuga, K.; Ikebe, K.; Ueda, T.; Tamura, F.; Nagao, K. Relationships between Deterioration of Oral Functions and Nutritional Status in Elderly Patients in an Acute Hospital. Jpn. J. Gerodontol. 2016, 31, 123–133. [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki, A.; Kaneko, H. Relationship between voluntary cough intensity and the respiratory, physical, oral and swallowing functions of the community-dwelling elderly. J. Phys. Ther. Sci. 2017, 32, 521–525. [Google Scholar]

- Oxman, T.E.; Berkman, L.F.; Kasl, S.; Freeman, D.H., Jr.; Barrett, J. Social support and depressive symptoms in the elderly. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1992, 135, 356–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harlow, S.D.; Goldberg, E.L.; Comstock, G.W. A longitudinal study of risk factors for depressive symptomatology in elderly widowed and married women. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1991, 134, 526–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanagisawa, S.; Baba, Y.; Ito, C.; Kobayashi, F.; Kusagawa, Y.; Kawai, F.; Yamahata, N.; Ohira, M. Effect of social support by family and friend on psychological QOL of the elderly. Jpn. J. Public Health 2002, 49, 766–773. [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe, Y.; Hirano, H.; Arai, H.; Morishita, S.; Ohara, Y.; Edahiro, A.; Murakami, M.; Shimada, H.; Kikutani, T.; Suzuki, T. Relationship Between Frailty and Oral Function in Community-Dwelling Elderly Adults. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2017, 65, 66–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwasaki, M.; Yoshihara, A.; Sato, N.; Sato, M.; Minagawa, K.; Shimada, M.; Nishimuta, M.; Ansai, T.; Yoshitake, Y.; Ono, T.; et al. A 5-year longitudinal study of association of maximum bite force with development of frailty in community-dwelling older adults. J. Oral Rehabil. 2018, 45, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payne, M.; Morley, J.E. Editorial: Dysphagia, Dementia and Frailty. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2018, 22, 562–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hihara, T.; Goto, T.; Ichikawa, T. Investigating Eating Behaviors and Symptoms of Oral Frailty Using Questionnaires. Dent. J. 2019, 7, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yoshii, K.; Kondo, K.; Kuze, J.; Higuchi, K. Social relationship factors and risk of care requirement in Japanese elderly. Jpn. J. Public Health 2005, 52, 456–467. [Google Scholar]

- Kishi, R.; Horikawa, N. Role of the social support network which influences age of death and physical function of elderly people: Study of trends in and outside of Japan and future problems. Jpn. J. Public Health 2004, 51, 79–93. [Google Scholar]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Buchner, A.; Lang, A.-G. Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behav. Res. Methods 2009, 41, 1149–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wang, J.; Hulme, C. Frailty and Socioeconomic Status: A Systematic Review. J. Public Health Res. 2021, 10, 2036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etman, A.; Kamphuis, C.B.M.; van der Cammen, T.J.M.; Burdorf, A.; van Lenthe, F.J. Do Lifestyle, Health and Social Participation Mediate Educational Inequalities in Frailty Worsening? Eur. J. Public Health 2015, 25, 345–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brunner, E.J.; Shipley, M.J.; Ahmadi-Abhari, S.; Valencia Hernandez, C.; Abell, J.G.; Singh-Manoux, A.; Kawachi, I.; Kivimaki, M. Midlife Contributors to Socioeconomic Differences in Frailty during Later Life: A Prospective Cohort Study. Lancet Public Health 2018, 3, e313–e322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Young-Old Adults (n = 39) | Old-Old Adults (n = 43) | p Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| age (years) | 70.5 | 2.8 | 78.7 | 2.9 | |

| gender (% female) | 87.2 | 67.4 | 0.034 * | ||

| Eleven Check (% risk) | 12.8 | 14.0 | 0.880 | ||

| Median | IQR | Median | IQR | ||

| oral functions | |||||

| occlusal force (%) | 89.7 | 95.3 | 0.330 | ||

| ODK (times/s) | 6.8 | 0.8 | 6.5 | 1.2 | 0.006 ** |

| GOHAI (point) | 57 | 9 | 56 | 6 | 0.374 |

| motor functions | |||||

| OLS (%) | 56.4 | 51.2 | 0.895 | ||

| LLC (cm) | 35.1 | 3.3 | 34.5 | 3.4 | 0.562 |

| GS (kg) | 25.6 | 5.5 | 22.5 | 11.4 | 0.130 |

| SMI (kg/m2) | 6.73 | 0.88 | 6.55 | 0.88 | 0.590 |

| social functions | |||||

| LSNS-6 (score) | 19.5 | 7 | 20.5 | 7 | 0.161 |

| organizational participation 9 (score) | 3 | 3 | 3.5 | 2 | 0.167 |

| social support (score) | 4 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 0.374 |

| Eleven Check | Occlusal Force | ODK | GOHAI | OLS | LLC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.077 | −0.06 | −0.262 * | −0.058 | 0.140 | −0.005 |

| GS | SMI | LSNS-6 | organizational participation | social support | |

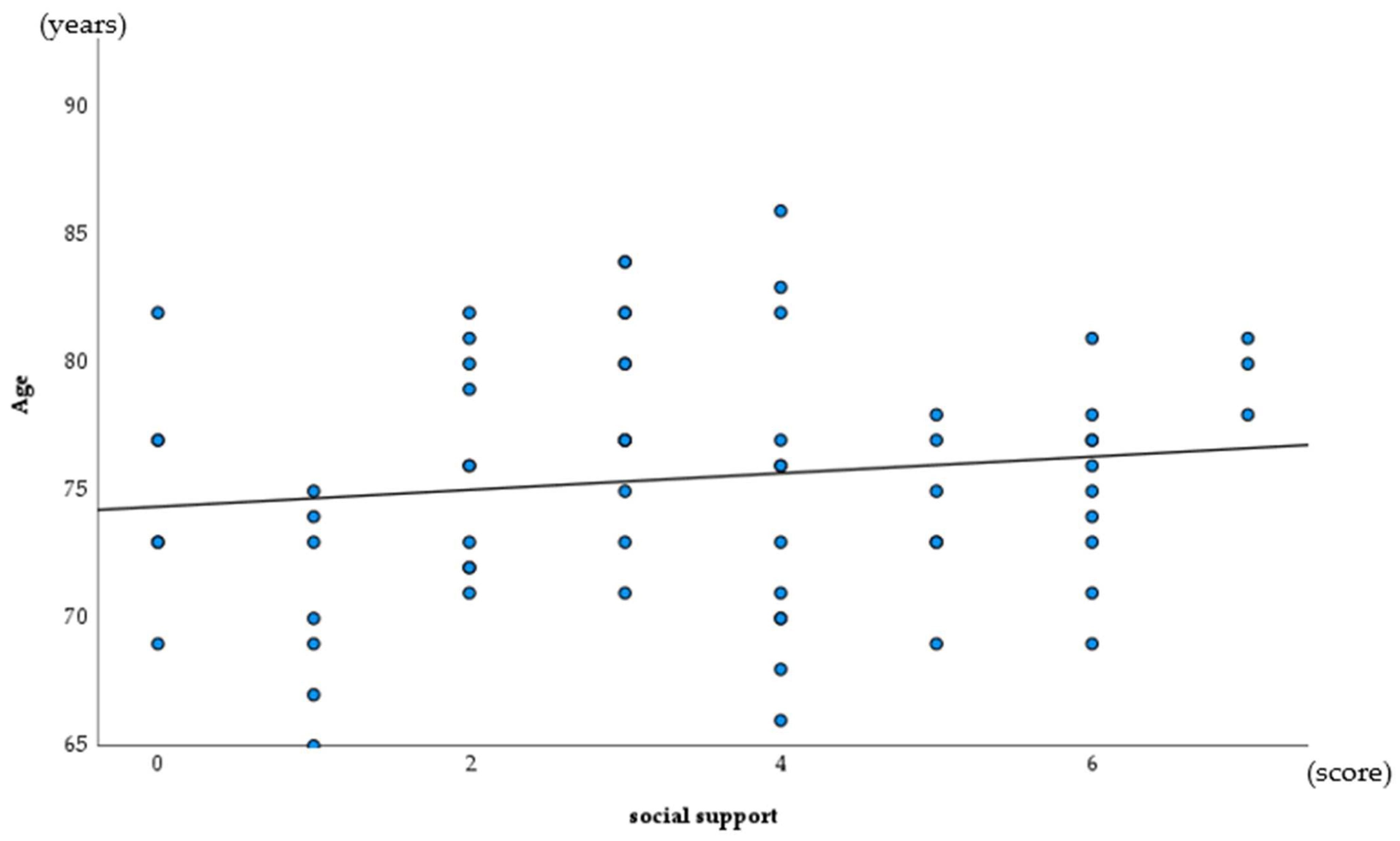

| −0.187 | −0.063 | 0.116 | 0.100 | −0.220 * |

| Coefficient (β) | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| occlusal force | −3.485 | 0.031 | 0.002, 0.430 | 0.01 * |

| GOHAI | −0.072 | 0.930 | 0.867, 0.999 | 0.046 * |

| social support | −0.220 | 0.803 | 0.690, 0.934 | 0.004 ** |

| constant | 8.134 | 0.004 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kodama, A.; Kume, Y.; Iwakura, M.; Iijima, K.; Ota, H. A Pilot Survey: Oral Function as One of the Risk Factors for Physical Frailty. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 6136. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19106136

Kodama A, Kume Y, Iwakura M, Iijima K, Ota H. A Pilot Survey: Oral Function as One of the Risk Factors for Physical Frailty. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(10):6136. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19106136

Chicago/Turabian StyleKodama, Ayuto, Yu Kume, Masahiro Iwakura, Katsuya Iijima, and Hidetaka Ota. 2022. "A Pilot Survey: Oral Function as One of the Risk Factors for Physical Frailty" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 10: 6136. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19106136

APA StyleKodama, A., Kume, Y., Iwakura, M., Iijima, K., & Ota, H. (2022). A Pilot Survey: Oral Function as One of the Risk Factors for Physical Frailty. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(10), 6136. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19106136