Taming Proteus: Challenges for Risk Regulation of Powerful Digital Labor Platforms

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Background and Analytical Framework

2.1. Digital Labor Platforms

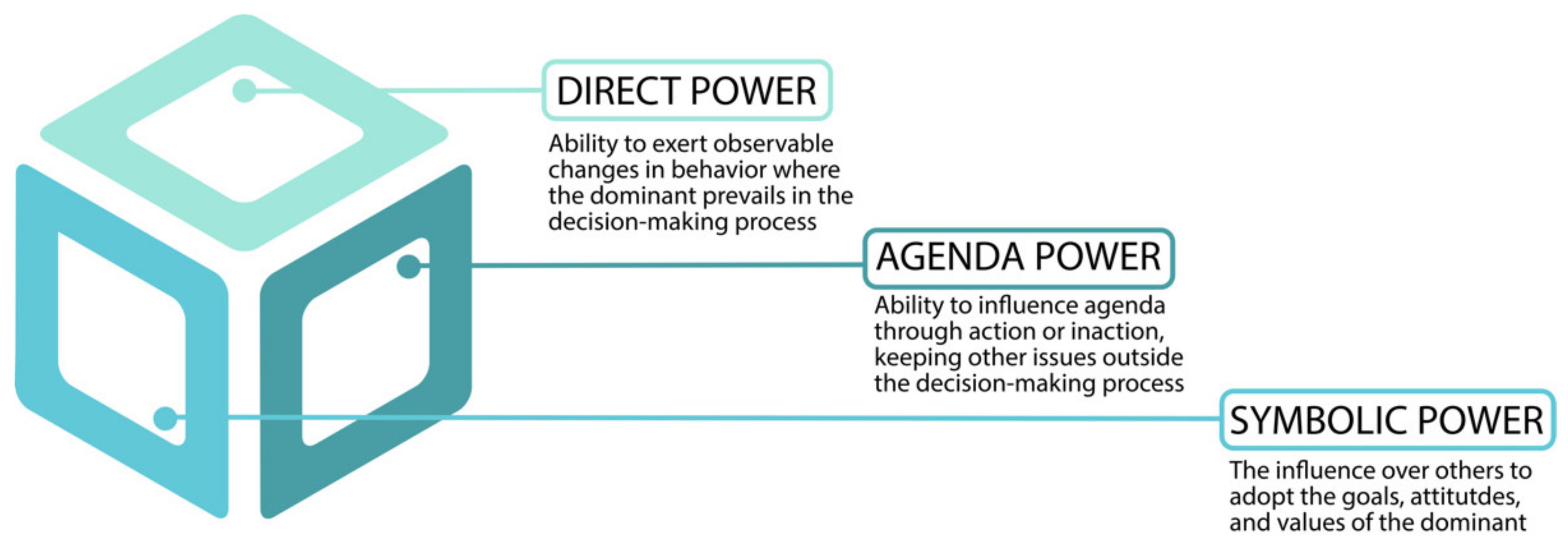

2.2. Power Dimensions and Digital Labor Platforms

2.2.1. Direct Control/One-Dimensional View of Power

2.2.2. Agenda Power/Two-Dimensional View of Power

2.2.3. Symbolic Power/Three-Dimensional View of Power

2.3. Regulation

2.4. The Norwegian Regulatory Context

2.4.1. Direct Control/One-Dimensional View of Power

2.4.2. Agenda Power/Two-Dimensional View of Power

2.4.3. Symbolic Power/Three-Dimensional View of Power

3. Methodology

4. Results

4.1. Working Conditions and Safety in PMW

One problem with being managed by an app is that training occurs virtually, which results in many not understanding its content, that someone else can take the course for you, or that your buddy can do the job in your name, no physical checks on the equipment. It’s pandemonium combined with people who do not have a clue about their rights and duties like accident reporting.(PC1, Employee-17)

It would be an easy job if all is well organized, […] it is sometimes absurd to just follow the app when it is wrong. […] The game is called follow the app.(PC1, Employee-8)

Sometimes, when there is traffic and I am late with the delivery, I drive past a yellow light and the police come. […] Yes, time pressure. There is a lot of traffic in the city center and sometimes I do not manage to be on time.(PC2, Freelancer-5)

The communication platform connecting [workers] directly to management has been removed; therefore, e-mails are the only point of contact.(PC1, Employee-14)

They changed it without talking with me actually. Basically, if I really want, I can put them in trouble because they changed it like this. They did not contact me because my contract says […]. That means I make more money actually, if I use the contract. But it is good, so I am not complaining because every day I get good money and focus on myself.(PC2, Freelancer-8)

[…] you are biking, you get the same app. Almost everything is the same. The only difference is that instead of receiving a salary, you get it in the form of reversed invoicing. But I perceive it as though I am almost employed at [PC1].(PC1, Freelancer-8)

Turnover is a term that is usually tied to permanent employment […] Turnover is not an important parameter when flexibility is in focus.(PC2, Management)

4.2. Gaps in the Regulation

4.2.1. Lack of Oversight

Under the Radar

Some of them are profoundly hidden away that we do not go on inspections there. We have all registered businesses in our system, including independent contractors and companies, but it depends on what they are registered under and if the information they provide is correct. We find inconsistencies with disclosed information when we go on inspections. […] Often, when we go on inspections, we find out that they are not directly linked to the organization number because they are registered under several organization numbers, meaning all are independent contractors. And when they are self-employed, it becomes very difficult to see how they are linked together.(Regulator-5)

Self-(Interested) Regulation and Technology

‘Oh, we are a different kind of company. We are doing things differently; therefore, different rules apply to us.’ NO, no, no, no! Labor laws have been established for a reason, and you are trying to get around it to increase your profits.(PC1, Employee-7)

4.2.2. Lack of Hindsight

Attention Deficits

First, development must occur; then we must say there is a problem, then we must have an opinion on how to solve the problem, then there must be political will to solve that [PMW] problem rather than other problems. And there are very many who have interests in the NLIA’s work, not only politicians but trade unions and large communities that have the tremendous political weight to control much of what NLIA prioritizes to do and implement. […] Unless there is a lot of fuss about the sharing economy, I do not think anything will happen either.(Regulator-3)

Old Problems in a New Guise

[…] I think there is a loophole in the law, which is harmful to society. It increases the disparities between ordinary incomes and low incomes. This means a development that is detrimental to society in the long run, so action must be taken there, politically.(PC1, Employee-17)

There is a difference between a dog walker and a self-employed doctor. They make different choices, have different opportunities, and have different starting points. Some have to accept what they get, while others can choose and are thus also in a better negotiating position due to their expertise. I usually say that people used to stand outside factories with a hat in their hand in the old days, hoping to get a job that day. You no longer do that, but you are connected to the app, and you hope to get that job that day.(Union-6)

4.2.3. Lack of Resight

Discontinuous Improvement

Getting a system to function is one thing, but people constantly leave, so one must start over frequently. You need to have good structure training. And how do you get involvement when people leave constantly? We need a new safety delegate, and the safety delegate must get training. Then we need new employees, and you don’t get continuity. Some do not care about the enterprise and just want to work and earn money. It is difficult to work towards a sound, continuous HSE system and be able to see its value along the way.(Regulator-5)

4.2.4. Lack of Foresight

[…] we work with risk-based regulation, which means we also need to distribute the 500 inspectors across the 250,000 business entities across Norway. We also need to make hard prioritizations when we go on inspections, provide guidance, supervise, and advise. Other parts of working life are more easily accessible to us that we have a better view of, and that becomes part of our work to a greater extent. […] We need to know that there is a working relationship in the platform economy before we can conduct an inspection or have anything to do with that matter.(Regulator-2)

5. Discussion

5.1. The Origins of Regulatory Gaps

5.2. Regulatory Escape

5.3. Could the Gaps Be Closed?

5.3.1. Strengthen Hindsight

5.3.2. Strengthen Oversight

5.3.3. Strengthen Foresight

5.3.4. Strengthen Resight

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Eurofound. The Digital Age: Implications of Automation, Digitisation and Platforms for Work and Employment, Challenges and Prospects in the EU Series; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Mattila-Wiro, P.; Samant, Y.; Husberg, W.; Falk, M.; Knudsen, A.; Saemundsson, E. Work Today and in the Future: Perspectives on Occupational Safety and Health Challenges and Opportunities for the Nordic Labour Inspectorates; Ministry of Social Affairs and Health: Helsinki, Finland, 2020.

- ILO. World Employment and Social Outlook: Trends 2022; International Labour Office: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- De Groen, W.P.; Kilhoffer, Z.; Westhoff, L.; Postica, D.; Shamsfakhr, F. Digital Labour Platforms in the EU. Mapping and Business Models; Final Report; CEPS: Brussels, Belgium, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Lenaerts, K.; Waeyaert, W.; Smits, I.; Hauben, H. Digital platform work and occupational safety and health: A policy brief. In Digital Platform Work: Occupational Safety and Health Policy and Practice for Risk Prevention and Management; KU Leuven: Leuven, Belgium, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Grote, G.; Weichbrodt, J. Why regulators should stay away from safety culture and stick to rules instead. In Trapping Safety into Rules; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2013; pp. 225–240. [Google Scholar]

- Størkersen, K.; Thorvaldsen, T.; Kongsvik, T.; Dekker, S. How deregulation can become overregulation: An empirical study into the growth of internal bureaucracy when governments take a step back. Saf. Sci. 2020, 128, 104772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldwin, R.; Cave, M.; Lodge, M. Understanding Regulation: Theory, Strategy, and Practice; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Lane, M. Regulating platform work in the digital age. In Going Digital Toolkit Policy Note; OECD: Paris, France, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Commission Proposals to Improve the Working Conditions of People Working through Digital Labour Platforms; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Drahokoupil, J.; Vandaele, K. Chapter 1. Introduction: Janus meets Proteus in the platform economy. In A Modern Guide to Labour and the Platform Economy; Edward Elgar Publishing: Northampton, MA, USA, 2021; p. 9. [Google Scholar]

- Ravenelle, A.J. Sharing economy workers: Selling, not sharing. Camb. J. Reg. Econ. Soc. 2017, 10, 281–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalleberg, A.L.; Dunn, M. Good jobs, bad jobs in the gig economy. LERA Libr. 2016, 20, 10–13. [Google Scholar]

- Parker, G.G.; Van Alstyne, M.W.; Choudary, S.P. Platform Revolution: How Networked Markets Are Transforming the Economy and How to Make Them Work for You; WW Norton & Company: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenblat, A.; Stark, L. Algorithmic labor and information asymmetries: A case study of Uber’s drivers. Int. J. Commun. 2016, 10, 3758–3784. [Google Scholar]

- Veen, A.; Barratt, T.; Goods, C. Platform-Capital’s ‘App-etite’ for Control: A Labour Process Analysis of Food-Delivery Work in Australia. Work. Employ. Soc. 2020, 34, 388–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, A.J.; Graham, M.; Lehdonvirta, V.; Hjorth, I. Good Gig, Bad Gig: Autonomy and Algorithmic Control in the Global Gig Economy. Work. Employ. Soc. 2019, 33, 56–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukes, S. Power: A Radical View; Macmillan International Higher Education: London, UK, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Ashby, W.R. An Introduction to Cybernetics; Chapman & Hall: London, UK, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Riso, S. Digital Age: Mapping the Countours of the Platform Economy; Eurofound: Dublin, Ireland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Schor, J.B.; Attwood-Charles, W. The “sharing” economy: Labor, inequality, and social connection on for-profit platforms. Sociol. Compass 2017, 11, e12493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huws, U.; Spencer, N.; Syrdal, D.S.; Holts, K. Work in the European Gig Economy: Research Results from the UK, Sweden, Germany, Austria, the Netherlands, Switzerland and Italy. Available online: https://uhra.herts.ac.uk/bitstream/handle/2299/19922/Huws_U._Spencer_N.H._Syrdal_D.S._Holt_K._2017_.pdf (accessed on 27 April 2021).

- ILO. World Employment and Social Outlook: The Role of Digital Labour Platforms in Transforming the World of Work; International Labour Office: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Codagnone, C.; Abadie, F.; Biagi, F. The Future of Work in the ‘Sharing Economy’. Market Efficiency and Equitable Opportunities or Unfair Precarisation? Institute for Prospective Technological Studies, Science for Policy Report by the Joint Research Centre, Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Platform for Shaping the Future of the New Economy and Society. The Promise of Platform Work: Understanding the Ecosystem; World Economic Forum: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Prassl, J. Humans as a Service: The Promise and Perils of Work in the Gig Economy; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2018; pp. 1–199. [Google Scholar]

- Eurofound. Back to the Future: Policy Pointers from Platform Work Scenarios; Mandl, I., Ed.; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Acquier, A.; Daudigeos, T.; Pinkse, J. Promises and paradoxes of the sharing economy: An organizing framework. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2017, 125, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurofound. Employment and Working Conditions of Selected Types of Platform Work; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2018; ISBN 9789289717489/9289717483. [Google Scholar]

- Lehdonvirta, V. Flexibility in the gig economy: Managing time on three online piecework platforms. New Technol. Work Employ. 2018, 33, 13–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, J.; Furrer, M.; Harmon, E.; Rani, U.; Silberman, M.S. Digital Labour Platforms and the Future of Work. Towards Decent Work in the Online World. Rapport de l’OIT; International Labour Office: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Garben, S. The regulation of platform work in the European Union: Mapping the challenges. In A Modern Guide to Labor and the Platform Economy; Edward Elgar Publishing: Northampton, MA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Thelen, K. Regulating Uber: The politics of the platform economy in Europe and the United States. Perspect. Politics 2018, 16, 938–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calo, R.; Rosenblat, A. The taking economy: Uber, information, and power. Columbia Law Rev. 2017, 117, 1623–1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coyle, D. Precarious and Productive Work in the Digital Economy. Natl. Inst. Econ. Rev. 2017, 240, R5–R14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollman, E. Tech, Regulatory Arbitrage, and Limits. Eur. Bus. Organ. Law Rev. 2019, 20, 567–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piasna, A.; Zwysen, W.; Drahokoupil, J. The Platform Economy in Europe. Results from the Second ETUI Internet and Platform Work Survey (IPWS); ETUI aisbl: Brussels, Belgium, 2022; p. 57. [Google Scholar]

- Schor, J.B.; Attwood-Charles, W.; Cansoy, M.; Ladegaard, I.; Wengronowitz, R. Dependence and precarity in the platform economy. Theory Soc. 2020, 49, 833–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quinlan, M. The Effects of Non-Standard Forms of Employment on Worker Health and Safety; ILO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Chai, S.; Scully, M.A. It’s About Distributing Rather than Sharing: Using Labor Process Theory to Probe the “Sharing” Economy. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 159, 943–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherry, M.A.; Aloisi, A. Dependent contractors in the gig economy: A comparative approach. Am. UL Rev. 2016, 66, 635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altinn. Freelancers. Available online: https://www.altinn.no/en/start-and-run-business/planning-starting/before-start-up/freelancers/ (accessed on 15 March 2022).

- Nielsen, M.L.; Laursen, C.S.; Dyreborg, J. Who takes care of safety and health among young workers? Responsibilization of OSH in the platform economy. Saf. Sci. 2022, 149, 105674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.K.; Kusbit, D.; Metsky, E.; Dabbish, L. Working with machines: The impact of algorithmic and data-driven management on human workers. In Proceedings of the 33rd Annual ACM Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Seoul, Korea, 18–23 April 2015; pp. 1603–1612. [Google Scholar]

- De Stefano, V.; Taes, S. Algorithmic Management and Collective Bargaining; ETUI: Brussels, Belgium, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, N.K. The Rating Game: The Discipline of Uber’s User-Generated Ratings. Surveill. Soc. 2019, 17, 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griesbach, K.; Reich, A.; Elliott-Negri, L.; Milkman, R. Algorithmic Control in Platform Food Delivery Work. Socius 2019, 5, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsen, M.; Kongsvik, T.; Almklov, P.G. Splintered structures and workers without a workplace: How should safety science address the fragmentation of organizations? Saf. Sci. 2022, 148, 105644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engen, O.A.; Lindøe, P.H. Coping with globalisation: Robust regulation and safety in high-risk industries. Saf. Sci. Res. Evolut. Chall. New Direct. 2019, 1, 55–73. [Google Scholar]

- Antonsen, S.; Almklov, P. Revisiting the issue of power in safety research. In Safety Science Research: Evolution, Challenges and New Directions; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2019; pp. 87–102. [Google Scholar]

- King, D.K.; Hayes, J. The effects of power relationships: Knowledge, practice and a new form of regulatory capture. J. Risk Res. 2018, 21, 1104–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsen, M.; Størkersen, K.V. Permitted to be powerful? A comparison of the possibilities to regulate safety in the Norwegian petroleum and maritime industries. Mar. Policy 2018, 92, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukes, S. Power and rational choice. J. Political Power 2021, 14, 281–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahl, R.A. The concept of power. Syst. Res. 1957, 2, 201–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukes, S. Power: A Radical View, 3rd ed.; Red Globe Press: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Bachrach, P.; Baratz, M.S. Two Faces of Power. Am. Political Sci. Rev. 1962, 56, 947–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukes, S. Power. Contexts 2007, 6, 59–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, M.L. Your job is about to get ‘taskified’; Forget the rise of robots. The immediate issue is the Uber-izing of human labor: 1. The Los Angeles Times, 8 January 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Almklov, P.G.; Antonsen, S. Standardisation and Digitalisation: Changes in Work as Imagined and What This Means for Safety Science. In Safety Science Research: Evolution, Challenges and New Directions; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2019; pp. 3–19. [Google Scholar]

- Duggan, J.; Sherman, U.; Carbery, R.; McDonnell, A. Algorithmic management and app-work in the gig economy: A research agenda for employment relations and HRM. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2020, 30, 114–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, P.V.; Joyce, S. Black box or hidden abode? The expansion and exposure of platform work managerialism. Rev. Int. Political Econ. 2020, 27, 926–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyers, Z. Driving Uncertainty: Labour Rights in the Gig Economy; Centre for European Reform: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- De Stefano, V.; Aloisi, A. European Legal Framework for ‘Digital Labour Platforms’; European Commission: Luxembourg, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Drahokoupil, J.; Piasna, A. Work in the Platform Economy: Beyond Lower Transaction Costs. Intereconomics 2017, 52, 335–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, X.; Joshi, K.; Galliers, R. The duality of empowerment and marginalization in microtask crowdsourcing: Giving voice to the less powerful through value sensitive design. Mis Q. 2016, 40, 279–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aloisi, A. Commoditized workers: Case study research on labor law issues arising from a set of on-demand/gig economy platforms. Comp. Lab. L. & Pol’y J. 2015, 37, 653. [Google Scholar]

- Kilhoffer, Z.; De Groen, W.P.; Lenaerts, K.; Smits, I.; Hauben, H.; Waeyaert, W.; Giacumacatos, E.; Lhernould, J.-P.; Robin-Olivier, S. Study to Gather Evidence on the Working Conditions of Platform Workers VT/2018/032 Final Report 13 December 2019; European Commission: Luxembourg, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, K.S.; Thelen, K. The Rise of the Platform Business Model and the Transformation of Twenty-First-Century Capitalism. Politics Soc. 2019, 47, 177–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Doorn, N. Platform labor: On the gendered and racialized exploitation of low-income service work in the ‘on-demand’ economy. Inf. Commun. Soc. 2017, 20, 898–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tansey, R.; Haar, K. Über-Influential; Corporate Europe Observatory and AK Europpa: Brussels, Belgium, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Collier, R.B.; Dubal, V.B.; Carter, C. Labor Platforms and Gig Work: The Failure to Regulate; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kenney, M.; Zysman, J. The rise of the platform economy. Issues Sci. Technol. 2016, 32, 61–69. [Google Scholar]

- Ahsan, M. Entrepreneurship and Ethics in the Sharing Economy: A Critical Perspective. J. Bus. Ethics 2020, 161, 19–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hood, C.; James, O.; Jones, G.; Scott, C.; Travers, T. Regulation Inside Government: Waste-Watchers, Quality Police, and Sleazebusters; OUP: Oxford, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- NLIA. About Us. Available online: https://www.arbeidstilsynet.no/en/about-us/ (accessed on 22 March 2022).

- Arbeidstilsynet. Årsrapport 2020. En Analyse av Arbeidstilsynets Innsats i 2020; Arbeidstilsynet: Trondheim, Norway, 2021.

- Dahl, Ø.; Rundmo, T.; Olsen, E. The Impact of Business Leaders’ Formal Health and Safety Training on the Establishment of Robust Occupational Safety and Health Management Systems: Three Studies Based on Data from Labour Inspections. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 31269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Det Kongelige Arbeids og Sosialdepatement. Tildelingsbrev 2020—Arbeidstilsynet; Arbeidstilsynet: Trondheim, Norway, 2020.

- Hansen, P.B.; Underthun, A. The Formation and Destabilization of the Standard Employment Relationship in Norway: The Contested Politics and Regulation of Temporary Work Agencies, 1st ed.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2019; pp. 320–338. [Google Scholar]

- Baram, M.; Lindøe, P.H. Modes of Risk Regulation for Prevention of Major Industrial Accidents; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2013; pp. 34–55. [Google Scholar]

- Lindøe, P.; Baram, M.; Braut, G. Empowered agents or empowered agencies? Assessing the risk regulatory regimes in the Norwegian and US offshore oil and gas industry. In Advances in Safety, Reliability and Risk Management; Taylor & Francis Group: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Lindøe, P.; Baram, M.; Braut, G.S. Risk regulation and proceduralization: An assessment of Norwegian and US risk regulation in offshore oil and gas industry. In Trapping Safety into Rules; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2017; pp. 69–86. [Google Scholar]

- Bryman, A. Social Research Methods, 5th ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Nigel, K.; Joanna, M.B. Doing Template Analysis: A Guide to the Main Components and Procedures; SAGE Publications Ltd.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017; p. 25. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brønnøysundregister. Industrial Codes. Available online: https://www.brreg.no/en/business-2/industrial-codes/?nocache=1648108312006 (accessed on 24 March 2022).

- Bain, V. Gig Workers Demand Occupational Death Benefits. Available online: https://www.coworker.org/petitions/gig-workers-demand-occupational-death-benefits?source=rawlink&utm_source=rawlink&share=fbe02a52-c869-4c7f-8bd1-62af1c4da092 (accessed on 24 March 2022).

- Fleming, P. The Human Capital Hoax: Work, Debt and Insecurity in the Era of Uberization. Organ. Stud. 2017, 38, 691–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EU. Transparency Register. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/transparencyregister/public/homePage.do?redir=false&locale=en (accessed on 4 March 2022).

- Brønnøysundregister. About the Register of Business Enterprises. Available online: https://www.brreg.no/en/about-us-2/our-tasks/all-our-registers/about-the-register-of-business-enterprises/ (accessed on 22 March 2022).

- Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs. Regulations Concerning Organisation, Management and Employee Participation; FOR-2011-12-06-1355; Arbeidstilsynet: Trondheim, Norway, 2020.

- Alsos, K.; Jesnes, K.; Sletvold Øistad, B.; Nesheim, T. Når Sjefen er en App; Fafo: Oslo, Norway, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Cutolo, D.; Kenney, M. Platform-dependent entrepreneurs: Power asymmetries, risks, and strategies in the platform economy. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2021, 35, 584–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Englert, S.; Graham, M.; Fredman, S.; du Toit, D.; Badger, A.; Heeks, R.; Van Belle, J.-P. Workers, platforms and the state: The struggle over digital labour platform regulation. In A Modern Guide to Labour and the Platform Economy; Edward Elgar Publishing: Northampton, MA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Nilsen, M.; Albrechtsen, E.; Nyheim, O.M. Changes in Norway’s societal safety and security measures following the 2011 Oslo terror attacks. Saf. Sci. 2018, 110, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindøe, P.H.; Engen, O.A.; Olsen, O.E. Responses to accidents in different industrial sectors. Saf. Sci. 2011, 49, 90–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birkland, T.A. After Disaster: Agenda Setting, Public Policy, and Focusing Events; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Birkmann, J.; Buckle, P.; Jaeger, J.; Pelling, M.; Setiadi, N.; Garschagen, M.; Fernando, N.; Kropp, J. Extreme events and disasters: A window of opportunity for change? Analysis of organizational, institutional and political changes, formal and informal responses after mega-disasters. Nat. Hazards 2008, 55, 637–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- March, J.G.; Olson, J.P. Organizing Political Life: What Administrative Reorganization Tells Us about Government. Am. Political Sci. Rev. 1983, 77, 281–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boin, A.; Hart, P.t. Public Leadership in Times of Crisis: Mission Impossible? Public Adm. Rev. 2003, 63, 544–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, B.N. Competition and Beyond: Problems and Attention Allocation in the Organizational Rulemaking Process. Organ. Sci. 2010, 21, 432–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- March, J.G.; Simon, H.A.; Guetzkow, H. Organizations; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1958. [Google Scholar]

- Fuller, C.W. An employee-management consensus approach to continuous improvement in safety management. Empl. Relat. 1999, 21, 405–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merriam-Webster. Merriam-Webster.com dictionary n.d. Available online: https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/resight (accessed on 22 March 2022).

- Almond, P.; Esbester, M. Regulatory inspection and the changing legitimacy of health and safety. Regul. Gov. 2018, 12, 46–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olberg, D. Endringer i arbeidslivets organisering–en introduksjon. Endringer Arb. Organ. 1995, 5, 28. [Google Scholar]

- Biber, E.; Light, S.E.; Ruhl, J.; Salzman, J. Regulating business innovation as policy disruption: From the model T to Airbnb. Vand. L. Rev. 2017, 70, 1561. [Google Scholar]

- Hale, A. Advancing robust regulation. In Risk Governance of Offshore Oil and Gas Operations; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2014; pp. 403–424. [Google Scholar]

- Lindøe, P.H. Safe off Shore Workers and Unsafe Fishermen—A System Failure? Policy Pract. Health Saf. 2007, 5, 25–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bank, M.; Duffy, F.; Leyendecker, V.; Silva, M. The Lobby Network: Big Tech’s Web of Influence in the EU; Corporate Europe Observatory: Brussels, Belgium; LobbyControl e.V.: Cologne, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Orlikowski, W.J. The duality of technology: Rethinking the concept of technology in organizations. Organ. Sci. 1992, 3, 398–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casilli, A.A. Global Digital Culture| Digital Labor Studies Go Global: Toward a Digital Decolonial Turn. Int. J. Commun. 2017, 11, 21. [Google Scholar]

- Barley, S.R.; Bechky, B.A.; Milliken, F.J. The Changing Nature of Work: Careers, Identities, and Work Lives in the 21st Century. Acad. Manag. Discov. 2017, 3, 111–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zysman, J.; Kenney, M. Intelligent Tools and Digital Platforms: Implications for Work and Employment. Intereconomics 2017, 52, 329–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Nilsen, M.; Kongsvik, T.; Antonsen, S. Working conditions and safety in the gig economy—A media coverage analysis. In Conference Paper: 30th European Safety and Reliability Conference and the 15th Probabilistic Safety Assessment and Management Conference; Research Publishing: Singapore, 2020; pp. 3172–3179. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston, H.; Land-Kazlauskas, C. Organizing on-demand: Representation, voice, and collective bargaining in the gig economy. In Conditions of Work and Employment Series; International Labour Office: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018; Volume 94. [Google Scholar]

- Tassinari, A.; Maccarrone, V. Riders on the Storm: Workplace Solidarity among Gig Economy Couriers in Italy and the UK. Work Employ. Soc. 2020, 34, 35–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Proposal for a Directive of the European Parliament and of the Council on Improving Working Conditions in Platform Work; COM(2021) 762; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Tran, M.; Sokas, R.K. The Gig Economy and Contingent Work: An Occupational Health Assessment. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2017, 59, e63–e66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs. Construction Client Regulations; FOR-2009-08-03-1028; Arbeidstilsynet: Trondheim, Norway, 2010.

- Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs. Framework Regulations; Arbeidstilsynet: Trondheim, Norway, 2010.

- Pulignano, V. Is the Glass Full or Still Half Empty? Reshaping Work; Financial Stability Board: Basel, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Bertolini, O.A.A.; Cant, C.; López, T.; Agüera, P.; Howson, K.; Graham, M. Gaps in the EU Directive Leave Most Vulnerable Platform Workers Unprotected; Reshaping Work; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2022. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nilsen, M.; Kongsvik, T.; Antonsen, S. Taming Proteus: Challenges for Risk Regulation of Powerful Digital Labor Platforms. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 6196. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19106196

Nilsen M, Kongsvik T, Antonsen S. Taming Proteus: Challenges for Risk Regulation of Powerful Digital Labor Platforms. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(10):6196. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19106196

Chicago/Turabian StyleNilsen, Marie, Trond Kongsvik, and Stian Antonsen. 2022. "Taming Proteus: Challenges for Risk Regulation of Powerful Digital Labor Platforms" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 10: 6196. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19106196

APA StyleNilsen, M., Kongsvik, T., & Antonsen, S. (2022). Taming Proteus: Challenges for Risk Regulation of Powerful Digital Labor Platforms. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(10), 6196. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19106196