Binge Eating Disorder Is a Social Justice Issue: A Cross-Sectional Mixed-Methods Study of Binge Eating Disorder Experts’ Opinions

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Recruitment

2.2. Procedure

2.3. Data Analysis

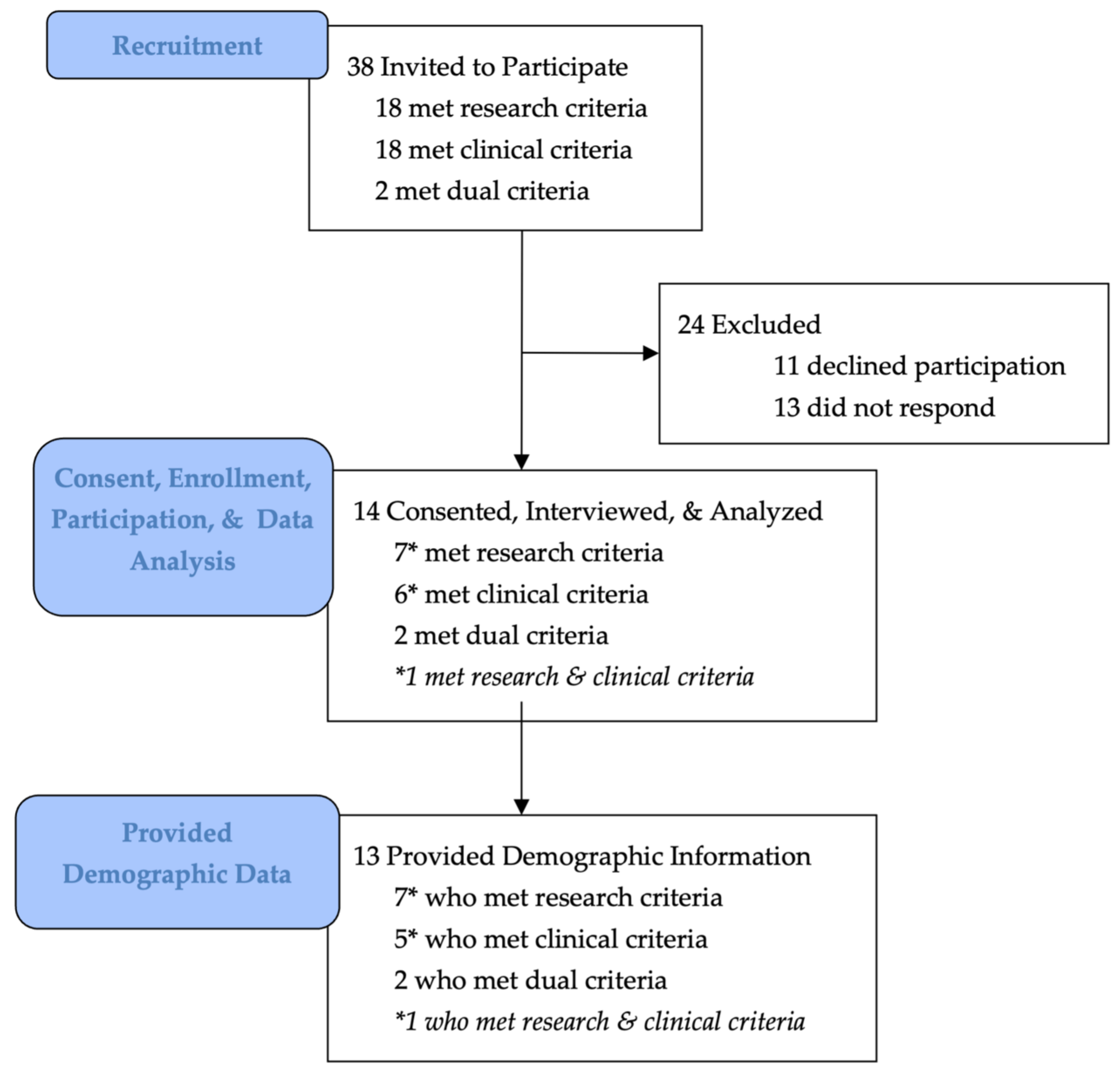

2.4. Participant Response Rates and Characteristics

3. Results

3.1. Theme 1: Systematic Issues and Systems of Oppression (14/14, 100%)

“If you work with eating disorders, it’s a political statement, [especially] as we’re [better] understanding [the impacts of] racial injustice. … targeting inequity, [is] going to have a cascading effect across mental illnesses, and especially the [way] we understand the impact of discrimination. … there’s no question we need to be thinking about …broad-based social factors related to poverty, related to stigma and weight stigma, obviously in binge eating, but frankly, you know, all types of stigma, all types of discrimination, because binge eating … crosses demographics, gender… [and] … my guess is binge eating disorder is horrifically under diagnosed among people who aren’t [currently] on our radar at all.”(P72)

“We are living in a society that’s so weight-focused and oppressive towards individuals living in like larger bodies… [and] …a lot of times, the demand to move has been …an oppressive demand upon the body and the psyche that is founded and shaming the person.”(P7)

3.2. Theme 2: Marginalized and Under-Represented Populations (14/14, 100%)

“If you’re a black woman, if you are somebody who lives in a larger body, if you are an older male, people aren’t going to think that your eating habits [constitute] an eating disorder because you aren’t … a young, thin, cis-gendered, white woman, and so I think that even just recognizing that binge eating disorder is ‘a thing’ is one of those things that gets in the way… I think it also makes sense to talk about the specific ways in which underrepresented groups might be struggling that are unique to them and their experiences versus just saying ‘anyone can be affected.’ …So knowing, for example, that if you are a sexual or gender minority you are at much greater risk of any kind of eating disorder behaviors, knowing that if you are a BIPOC member of a community you are very unlikely to get detected with an eating disorder, and that means you could struggle for a long time, and what do we do then to reach these communities in a way that’s meaningful?”(P75)

3.3. Theme 3: Economic, Food, and Nutrition Scarcity and Insecurity (13/14, 93%)

3.3.1. Subtheme i: Economic Precarity (93%)

“If [an individual’s] economic status is not as good, their physical health status will be not as good and their mental health status will be not as good and we know that socioeconomic disadvantage is a major player in terms of risk for …perpetuation of illness, for maintenance of illness. And sometimes for, … the onset of illness as well. …socioeconomic disadvantaged groups in the community have poorer mental health, we know that. So, it is really important.”(P93)

3.3.2. Subtheme ii: Food Scarcity & Insecurity (64%)

“I work with patients who have said, ‘well yeah, I have binge eating. I binge eat the first two weeks of the month ‘cause that’s when we have food in the house and then there’s no food in the house the last two weeks of the month.’ That’s a systemic issue that I think needs to be addressed and needs to be talked about in terms of people’s vulnerability to eating disorders.”(P75)

3.3.3. Subtheme iii: Nutritional Scarcity & Undernutrition (43%)

“We know that poor people have less access to nutritious foods and have a food environment that I think is predatory, to push, you know, highly processed foods …Even our fruits and vegetables, because of soil and farming practices have become less nutritious.”(P19)

3.4. Theme 4: Stigmatization and Its Psychological Impacts (13/14, 93%)

3.4.1. Subtheme i: Forms of Stigmatization (93%)

“People with eating disorders, they struggle with mental health stigma, they struggle with eating disorder stigma, and they struggle with weight stigma. [So those are] three [forms of stigmatization that can] obviously can impact [individuals with binge eating disorder] in very severe ways.”(P93)

“… the stereotypical [judgement is] that someone in a larger body is a failure, is lazy, is all these negative things…”(P37)

“Anytime you’re given the message overt or covert, that something is… wrong with you, like you’re bad, you’re too much, you’re big, you’re repulsive, you’re gluttonous, whatever, … that’s really the message that people internalize through a lot of experiences with healthcare practice, practitioners, families, schools, etc.”(P7)

3.4.2. Subtheme ii: Body Weight/Shape/Size Stigmatization (93%)

“The police are to black men as the medical establishment is to black women”(P72)

“I have a patient with binge eating disorder whose doctor told her, ‘you’re fat every day, so you should exercise every day.’ That’s from a health care practitioner. But that’s really …what we’re telling people [as a culture/society] …the practitioner just put [it into] words.”(P7)

3.4.3. Subtheme iii: Body Weight/Shape/Size Discrimination (21%)

3.5. Theme 5: Trauma and Adversity (11/14, 79%)

3.5.1. Subtheme i: Forms of Trauma/Adversity (50%)

“[There’s] lots of research showing that traumatic early life experiences, sexual abuse, but also other forms of abuse, emotional and physical abuse, increased someone’s risk for an eating disorder.”(P93)

“If the eating disorder has been associated with weight gain, then we know for a fact that they’ve been intruded upon by families, doctors, … institutions, and … there’s trauma associated with that. There’s trauma [associated] with …being told day in and day out that what you are is not acceptable or lovable or okay.”(P7)

“… trauma of physical activity … the idea that they don’t want to work out, but it’s really that their middle school teacher was screaming at them when they were trying to do their …whatever… PE class, or they got made fun of.”(P37)

“Trauma is so bad for the brain and what we’re seeing around ‘little t trauma,’ if you are someone [who is] susceptible, and you are teased and bullied, I think there’s a lifelong consequence for a lot of those individuals, and I think that absolutely sets up the trajectory around eating dysregulation, no question about it.”(P72)

3.5.2. Subtheme ii: Relationship between Trauma/Adversity and Binge Eating Disorder Pathology (79%)

“We know that people who are traumatized can have some upsetting of their arousal responses [that is] biological, and that … managing [and] down-regulating [the hyper-arousal response] is an important part of therapy often. …We know that there are biological brain changes [that occur] as a consequence of repeated adverse life experiences or traumatic experiences. We know that post-traumatic stress disorder is a disorder that is a common outcome, but that people can [also] develop other disorders, which are not PTSD, but that occur as a consequence [of repeated traumatic or adverse life experiences]. …As part of that dysregulation of emotions and those experiences, binge eating can [become] a way of modulating those emotions. … it’s a real phenomenon and a real effect, and lots of research [shows] that traumatic early life experiences, sexual abuse, but also other forms of abuse, emotional and physical abuse, increase someone’s risk for an eating disorder.”(P93)

3.5.3. Subtheme iii: Critical Considerations (36%)

“To what degree do we understand any trauma that somebody with binge eating disorder has experienced throughout their life, either singularly or multiple times? And how does that play a role in … their current experience? And [trauma] can be specific …traumatic events, it can be the ongoing impact of chronic stress related to either low level trauma or the trauma of chronic racism or the trauma of chronic weight stigma. And so how do we think about that and where does that fit into… our treatments?”(P60)

3.6. Theme 6: Interpersonal Factors (9/14, 64%)

3.6.1. Subtheme i: Ways Interpersonal Factors Can Impact Binge Eating Disorder (50%)

“Any form of interpersonal deficits or a struggle in terms of sustaining, maintaining good quality relationships in life and having people [to] confide in is an important vulnerability factor for an eating disorder, but also may probably help explain why interpersonal psychological therapy and addressing interpersonal deficits is an effective treatment in controlled trials.”(P93)

3.6.2. Subtheme ii: Ways Binge Eating Disorder Can Impact Interpersonal Factors (36%)

“As a field … we neglect social anxiety disorder because we tend to think it’s just about weight and shape, self-consciousness, I think we under-diagnose this. … we need to be looking specifically at Social Anxiety Disorder and I think based on Janet Treasurer’s work, we’re going to end up seeing that there’s links in …sensitivity to social threat, … the extent to which that’s causal, secondary to the eating disorder … understanding where anxieties sort of intersect and [understanding the] neurocognitive process …especially around threat sensitivity… is going to be really helpful.”(P72)

3.6.3. Subtheme iii: Positive Relationships between Social Interaction and Binge Eating Disorder Pathology (21%)

“[Social support] has an enormous impact not just on your behavior, but on you know, your brain functioning, honestly, I mean, it means you are in a community you are being cared for you are accountable.”(P72)

3.7. Theme 7: Social Messaging and Social Media (7/14, 50%)

“If you look at social media, the amount of blaming and stigmatizing and the link still… between … character and weight and shape and the role of thin privilege. I really do believe that if we can shift some of that it’s going to have broader based implications around eating disorders, especially—frankly—binge eating, because people tend to be higher weighted.”(P72)

“Social media is horrible with the way it advertises all kinds of stuff …food advertising and weight stigma, and then diet pills and weight loss products… …people are being bombarded with all of that all the time when they’re online.”(P16)

“You just have to look at social media to realize other people can be part problem as well, as part of the solution.”(P84)

3.8. Theme 8: Predatory Food Industry Practices and Environments (4/14, 29%)

“The question of political utility is something which we don’t usually talk about in science, but I saw the nutritional epidemiology field paying attention to the emotional aspects of overeating and the emotional and physiological aspects of the way processed foods are created to promote overeating by tapping into physiological responses to fat, sugar, crunch, salt……There’s so many processed foods that are designed to get people to overeat or to … trigger an emotional response that then [makes] someone prone to binge eating as a way of emotionally coping with things that are happening around them that feel out of their control or that are damaging to them. …There’s so many different systems; the food system is one of them.…The food industry and generation of processed foods [are] part of … the landscape that aids and abets binge eating and binge eating disorder. [They impact] what the food landscape looks like and there’s people profiting off of that. During this past 42 min …there are companies and individuals profiting off of making food that will lead someone down a path to binge eating disorder or binge eating… If that’s not a system of oppression I don’t know what is.”(P16)

“With … tobacco, …we were working on these treatments, and pharmacology, and all these sorts of things, and we really didn’t start to see drops in [tobacco use] until we changed the tobacco environment. … Leaning on a public health perspective … what have we done … to reduce people’s tendency to overuse [things like tobacco] or with alcohol too … we really focused on altering the environment, so, there’s not as much marketing, there’s not as many triggers, it’s not in your face, it’s not in vending machines, it’s not targeted to kids, it’s more expensive. And so, I think of all of those … environmental interventions… …if you can have a more optimal environment that encourages …healthy eating, and there’s not as much temptation, that allows our individual treatments to have a better chance for success. Because if you’re trying to use … individual treatments to combat a truly oppressive food environment, that’s a really tall order.”(P19)

“To ignore the fact that the food environment has changed, and that we are all kind of dealing with …predatory industry practices, but with very hyper-engineered, highly rewarding foods, to not acknowledge that in any way is problematic, and I think not giving people …the full picture of what they are dealing with. … [If you’re] sitting down with a bowl of ice cream and a bowl of salad, you’re dealing with fundamentally …very different things from …a reward, and even a psychological … profile. And so, it’s not just that… ‘if you just tried hard enough, … you’d … just be able to sort this out very easily.’ …under-selling the challenge of our food environment and the foods that we’re dealing with, especially [for those who] are under-resourced, [is] not giving people the full picture.”(P19)

“I have people [who] think that they’re addicted to food. Once we normalize that food, though, then it’s like, ‘oh, okay, I can have cheesecake for my snack. Awesome,’.”(P37)

3.9. Theme 9: Research Gaps and Future Directives (14/14, 100%)

3.9.1. Subtheme i: Systemic Changes (71%)

“I think we’re very underfunded in terms of treatment trials, and …woefully underfunded when we compare ourselves with high weight disorders. … …and just generally, across the board, we need …more funding for research…”(P93)

“I think that there’s a professional socio-cultural administrative framework that is having trouble getting its arms around binge eating disorder…”(P33)

“I think I’ll just go back to the food systems issue, the manufacturers of processed foods. …That’s the one that … we need whole cohorts of graduates from public health schools and psychology and some other fields just to document what’s happening there and work with policymakers to change what food manufacturers are allowed to do.”(P16)

3.9.2. Subtheme ii: Understanding Environmental Impacts (36%)

3.9.3. Subtheme iii: Including Marginalized Populations (29%)

“I think it …makes sense to talk about the specific ways in which underrepresented groups might be struggling that are unique to them and their experiences …and what do we do then to reach these communities in a way that’s meaningful?”(P75)

3.9.4. Subtheme iv: Recognizing and Understanding Weight Bias, Stigma, & Discrimination (29%)

“Weight bias affects researchers and clinicians in the field of eating disorders the same way it affects everyone, everywhere. …I thought I was not weight-biased, but somebody [who focuses on weight bias professionally] said, to me, …’well, of course, you have weight bias; everyone has weight bias,’ and … I’ve thought about it and [I] realize… I do [have weight bias] …it’s so much [a] part of the scenery …that you don’t even … recognize how much it affects how you perceive things. … I think there’s a lot of people who don’t recognize that.”(P38)

3.9.5. Subtheme v: Taking, Understanding, and Accounting for the Narrative (21%)

“… [I] think …we should be taking account of people’s narrative and life experiences and that should be informing our therapy and our therapeutic approaches.”(P93)

3.9.6. Subtheme vi: Understanding Consequences of Binge Eating Disorder (14%)

4. Discussion

4.1. Analysis Results

4.1.1. Theme 1: Systematic Issues and Systems of Oppression (100% Expert Identification)

4.1.2. Theme 2: Marginalized and Under-Represented Populations (100%)

4.1.3. Theme 3: Economic, Food, and Nutrition Scarcity and Insecurity (93%)

4.1.4. Theme 4: Stigmatization and Its Psychological Impacts (93%)

4.1.5. Theme 5: Trauma and Adversity (79%)

4.1.6. Theme 6: Interpersonal Factors (Threat & Threat Sensitivity) (64%)

4.1.7. Theme 7: Social Messaging and Social Media (50%)

4.1.8. Theme 8: Predatory Food Industry Practices (29%)

4.1.9. Theme 9: Accounting for Narratives & Life Experiences through Open-Ended Research

4.2. Expert Demographics

4.3. Study Limitations

4.4. Study Strengths

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- American Psychiatric Association (APA). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Association: Arlington, VA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hudson, J.I.; Hiripi, E.; Pope, H.G., Jr.; Kessler, R.C. The prevalence and correlates of eating disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Biol. Psychiatry 2007, 61, 348–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Termorshuizen, J.D.; Watson, H.J.; Thornton, L.M.; Borg, S.; Flatt, R.E.; MacDermod, C.M.; Harper, L.E.; van Furth, E.F.; Peat, C.M.; Bulik, C.M. Early impact of COVID-19 on individuals with self-reported eating disorders: A survey of ~1000 individuals in the United States and the Netherlands. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2020, 53, 1780–1790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mustelin, L.; Bulik, C.M.; Kaprio, J.; Keski-Rahkonen, A. Prevalence and correlates of binge eating disorder related features in the community. Appetite 2017, 109, 165–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kessler, R.C.; Berglund, P.A.; Chiu, W.T.; Deitz, A.C.; Hudson, J.I.; Shahly, V.; Aguilar-Gaxiola, S.; Alonso, J.; Angermeyer, M.C.; Benjet, C.; et al. The prevalence and correlates of binge eating disorder in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. Biol. Psychiatry 2013, 73, 904–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Frank, G.K.W.; Berner, L.A. (Eds.) Binge Eating: A Transdiagnostic Psychopathology; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Culbert, K.M.; Racine, S.E.; Klump, K.L. Research Review: What we have learned about the causes of eating disorders—A synthesis of sociocultural, psychological, and biological research. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry Allied Discip. 2015, 56, 1141–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javaras, K.N.; Laird, N.M.; Reichborn-Kjennerud, T.; Bulik, C.M.; Pope, H.G., Jr.; Hudson, J.I. Familiality and heritability of binge eating disorder: Results of a case-control family study and a twin study. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2008, 41, 174–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, K.S.; Neale, M.C.; Bulik, C.M.; Aggen, S.H.; Kendler, K.S.; Mazzeo, S.E. Binge eating disorder: A symptom-level investigation of genetic and environmental influences on liability. Psychol. Med. 2010, 40, 1899–1906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, J.I.; Lalonde, J.K.; Berry, J.M.; Pindyck, L.J.; Bulik, C.M.; Crow, S.J.; McElroy, S.L.; Laird, N.M.; Tsuang, M.T.; Walsh, B.T.; et al. Binge-eating disorder as a distinct familial phenotype in obese individuals. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2006, 63, 313–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Reichborn-Kjennerud, T.; Bulik, C.M.; Tambs, K.; Harris, J.R. Genetic and environmental influences on binge eating in the absence of compensatory behaviors: A population-based twin study. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2004, 36, 307–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichborn-Kjennerud, T.; Bulik, C.M.; Kendler, K.S.; Røysamb, E.; Maes, H.; Tambs, K.; Harris, J.R. Gender differences in binge-eating: A population-based twin study. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2003, 108, 196–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, J.K.; Stice, E. Thin-Ideal Internalization: Mounting Evidence for a New Risk Factor for Body-Image Disturbance and Eating Pathology. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2001, 10, 181–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hohlstein, L.A.; Smith, G.T.; Atlas, J.G. An application of expectancy theory to eating disorders: Development and validation of measures of eating and dieting expectancies. Psychol. Assess. 1998, 10, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oxford Languages. Social Justice 2022. Available online: https://languages.oup.com/google-dictionary-en/ (accessed on 26 August 2021).

- Corsino, L.; Fuller, A.T. Educating for diversity, equity, and inclusion: A review of commonly used educational approaches. J. Clin. Transl. Sci. 2021, 5, e169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institutes of Health Office of Intramural Research. Our Commitment to Diversity and Inclusion. 26 March 2021. Available online: https://oir.nih.gov/about/our-commitment-diversity-inclusion (accessed on 11 May 2022).

- Janse van Rensburg, M. COVID19, the pandemic which may exemplify a need for harm-reduction approaches to eating disorders: A reflection from a person living with an eating disorder. J. Eat. Disord. 2020, 8, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keski-Rahkonen, A. Epidemiology of binge eating disorder: Prevalence, course, comorbidity, and risk factors. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2021, 34, 525–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenny, T.E.; Boyle, S.L.; Lewis, S.P. #recovery: Understanding recovery from the lens of recovery-focused blogs posted by individuals with lived experience. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2020, 53, 1234–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondü, R.; Bilgin, A.; Warschburger, P. Justice sensitivity and rejection sensitivity as predictors and outcomes of eating disorder pathology: A 5-year longitudinal study. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2020, 53, 926–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Academy for Eating Disorders (AED). About AED: Honors & Awards. 2020. Available online: https://www.aedweb.org/about-aed/honors-awards (accessed on 16 August 2021).

- Castle Connolly Top Doctors. 2021. Available online: https://www.castleconnolly.com/search?q=&postalCode=30301&location=Atlanta%2C+GA&tf1=5117bfc9-a93e-3ba3-82f1-73359a3d585e&distanceParam=100000&sp=0000016e-f5fd-d509-a36e-f7fdc66e001e&exp=0000016e-f6c9-d155-a9ee-f7db2825002a (accessed on 16 August 2021).

- Academy for Eating Disorders (AED). About AED: AED Fellows. 2020. Available online: https://www.aedweb.org/aedold/about/fellows (accessed on 16 August 2021).

- The National Eating Disorders Association (NEDA). NEDA Treatment Providers. 2018. Available online: https://map.nationaleatingdisorders.org (accessed on 7 January 2022).

- National Alliance for Eating Disorders. Treatment Center & Practitioner Directory. 2022. Available online: https://findedhelp.com (accessed on 7 January 2021).

- Goode, E. Centers to Treat Eating Disorders Are Growing, and Raising Concerns. The New York Times. 14 March 2016. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2016/03/15/health/eating-disorders-anorexia-bulimia-treatment-centers.html (accessed on 7 January 2021).

- Linardon, J. 15 Best Eating Disorder Books of All-Time to Improve Your Eating Behaviors. 2021. Available online: https://BreakBingeEating.com (accessed on 15 August 2021).

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. One size fits all? What counts as quality practice in (reflexive) thematic analysis? Qual. Res. Psychol. 2021, 18, 328–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, C. Geographic Inequities in SNAP Limit Its Effectiveness. Nonprofit Quarterly. 24 July 2018. Available online: https://nonprofitquarterly.org/geographic-inequities-in-snap-limit-its-effectiveness/ (accessed on 12 February 2022).

- Hoynes, H.W.; Ziliak, J.P. Increasing SNAP Purchasing Power Reduces Food Insecurity and Improves Child Outcomes. Brookings. 24 July 2018. Available online: https://www.brookings.edu/blog/up-front/2018/07/24/increasing-snap-purchasing-power-reduces-food-insecurity-and-improves-child-outcomes/ (accessed on 12 February 2022).

- Ziliak, J.P. Modernizing SNAP Benefits. Center for Poverty Research, Department of Economics, University of Kentucky. 2016. Available online: https://www.hamiltonproject.org/assets/files/ziliak_modernizing_snap_benefits.pdf (accessed on 12 February 2022).

- Arnold, N.S. Economic Exploitation. In Philosophy and Economics of Market Socialism: A Critical Study; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Becker, C.B.; Middlemass, K.; Taylor, B.; Johnson, C.; Gomez, F. Food insecurity and eating disorder pathology. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2017, 50, 1031–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hay, P.; Mitchison, D. Urbanization and eating disorders: A scoping review of studies from 2019 to 2020. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2021, 34, 287–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doku, D.T.; Neupane, S. Double burden of malnutrition: Increasing overweight and obesity and stall underweight trends among Ghanaian women. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Freire, W.B.; Waters, W.F.; Rivas-Mariño, G.; Belmont, P. The double burden of chronic malnutrition and overweight and obesity in Ecuadorian mothers and children, 1986–2012. Nutr. Health 2018, 24, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobylinska, M.; Antosik, K.; Decyk, A.; Kurowska, K. Malnutrition in Obesity: Is It Possible? Obes. Facts 2022, 15, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Via, M. The malnutrition of obesity: Micronutrient deficiencies that promote diabetes. ISRN Endocrinol. 2012, 2012, 103472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- World Health Organization. Malnutrition. 9 June 2021. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/malnutrition (accessed on 25 March 2022).

- Keys, A.; BroŽEk, J.; Henschel, A.; Mickelsen, O.; Taylor, H.L.; Simonson, E.; Skinner, A.S.; Wells, S.M.; Drummond, J.C.; Wilder, R.M.; et al. The Biology of Human Starvation; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 1950; Volume I. [Google Scholar]

- Parlee, S.D.; MacDougald, O.A. Maternal nutrition and risk of obesity in offspring: The Trojan horse of developmental plasticity. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2014, 1842, 495–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Aamodt, S. Why Diets Make Us Fat: The Unintended Consequences of Our Obsession with Weight Loss; CURRENT, An Imprint of Penguin Random House LLC: New York, NY, USA, 2016; Available online: https://u1lib.org/book/2799683/d3ce5c (accessed on 15 February 2022).

- Tripicchio, G.L.; Keller, K.L.; Johnson, C.; Pietrobelli, A.; Heo, M.; Faith, M.S. Differential maternal feeding practices, eating self-regulation, and adiposity in young twins. Pediatrics 2014, 134, e1399–e1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Janeway, H.; Coli, C.J. Emergency care for transgender and gender-diverse children and adolescents. Pediatr. Emerg. Med. Pr. 2020, 17, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- James, S.E.; Herman, J.L.; Rankin, S.; Keisling, M.; Mottet, L.; Anafi, M. The Report of the 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey. 2016. Available online: https://transequality.org/sites/default/files/docs/usts/USTS-Full-Report-Dec17.pdf (accessed on 25 March 2022).

- Linsenmeyer, W.R.; Katz, I.M.; Reed, J.L.; Giedinghagen, A.M.; Lewis, C.B.; Garwood, S.K. Disordered Eating, Food Insecurity, and Weight Status Among Transgender and Gender Nonbinary Youth and Young Adults: A Cross-Sectional Study Using a Nutrition Screening Protocol. LGBT Health 2021, 8, 359–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Economic Research Service, United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). Food Security and Nutrition Assistance. 8 November 2021. Available online: https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/ag-and-food-statistics-charting-the-essentials/food-security-and-nutrition-assistance (accessed on 25 March 2022).

- United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). Economic Research Service Using Data from Current Population Survey Food Security Supplement, U.S. Census Bureau. 2020. Available online: https://www2.census.gov/programs-surveys/cps/techdocs/cpsdec20.pdf (accessed on 25 March 2022).

- Sutin, A.; Robinson, E.; Daly, M.; Terracciano, A. Weight discrimination and unhealthy eating-related behaviors. Appetite 2016, 102, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Assari, S. Perceived Discrimination and Binge Eating Disorder; Gender Difference in African Americans. J. Clin. Med. 2018, 7, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kelly, N.R.; Smith, T.M.; Hall, G.C.N.; Guidinger, C.; Williamson, G.; Budd, E.L.; Giuliani, N.R. Perceptions of general and postpresidential election discrimination are associated with loss of control eating among racially/ethnically diverse young men. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2018, 51, 28–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pearl, R.L.; Wadden, T.A.; Tronieri, J.S.; Chao, A.M.; Alamuddin, N.; Berkowitz, R.I. Everyday discrimination in a racially diverse sample of patients with obesity. Clin. Obes. 2018, 8, 140–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beccia, A.L.; Jesdale, W.M.; Lapane, K.L. Associations between perceived everyday discrimination, discrimination attributions, and binge eating among Latinas: Results from the National Latino and Asian American Study. Ann. Epidemiol. 2020, 45, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelly, N.R.; Cotter, E.W.; Guidinger, C.; Williamson, G. Perceived discrimination, emotion dysregulation and loss of control eating in young men. Eat. Behav. 2020, 37, 101387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.K.; Berry, D.C.; Schwartz, T.A. Weight Stigmatization and Binge Eating in Asian Americans with Overweight and Obesity. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grunewald, W.; Convertino, A.D.; Safren, S.A.; Mimiaga, M.J.; O’Cleirigh, C.; Mayer, K.H.; Blashill, A.J. Appearance discrimination and binge eating among sexual minority men. Appetite 2021, 156, 104819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, T.B.; Mozdzierz, P.; Wang, S.; Smith, K.E. Discrimination and Eating Disorder Psychopathology: A Meta-Analysis. Behav. Ther. 2021, 52, 406–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, R.J.; Veale, J.F.; Saewyc, E.M. Disordered eating behaviors among transgender youth: Probability profiles from risk and protective factors. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2017, 50, 515–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Himmelstein, M.S.; Puhl, R.M.; Quinn, D.M. Overlooked and Understudied: Health Consequences of Weight Stigma in Men. Obesity 2019, 27, 1598–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wellman, J.D.; Araiza, A.M.; Solano, C.; Berru, E. Sex differences in the relationships among weight stigma, depression, and binge eating. Appetite 2019, 133, 166–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, T.B.; Smith, K.E.; Lavender, J.M. Stigma control model of dysregulated eating: A momentary maintenance model of dysregulated eating among marginalized/stigmatized individuals. Appetite 2019, 132, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ancheta, A.J.; Caceres, B.A.; Zollweg, S.S.; Heron, K.E.; Veldhuis, C.B.; VanKim, N.A.; Hughes, T.L. Examining the associations of sexual minority stressors and past-year depression with overeating and binge eating in a diverse community sample of sexual minority women. Eat. Behav. 2021, 43, 101547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, K.H.; Glantz, S.A.; Palmer, C.N.; Schmidt, L.A. Transferring Racial/Ethnic Marketing Strategies From Tobacco to Food Corporations: Philip Morris and Kraft General Foods. Am. J. Public Health 2020, 110, 329–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egbert, A.; Hunt, R.A.; Burke, N.L.; Mathis, K.J. Reporting Racial and Ethnic Diversity in Eating Disorder Research Over the Past 20 Years. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2021, 55, 455–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, A.E.; Franko, D.L.; Speck, A.; Herzog, D.B. Ethnicity and differential access to care for eating disorder symptoms. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2003, 33, 205–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, K.H.; Brattole, M.M.; Wingate, L.R.; Joiner, T.E., Jr. The impact of client race on clinician detection of eating disorders. Behav. Ther. 2006, 37, 319–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonneville, K.R.; Lipson, S.K. Disparities in eating disorder diagnosis and treatment according to weight status, race/ethnicity, socioeconomic background, and sex among college students. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2018, 51, 518–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deloitte Access Economics; The Academy for Eating Disorders. The Social and Economic Cost of Eating Disorders in the United States of America: A Report for the Strategic Training Initiative for the Prevention of Eating Disorders and the Academy for Eating Disorders. 2020. Available online: https://www.hsph.harvard.edu/striped/report-economic-costs-of-eating-disorders/ (accessed on 7 March 2021).

- Perez, M.; Ohrt, T.K.; Hoek, H.W. Prevalence and treatment of eating disorders among Hispanics/Latino Americans in the United States. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2016, 29, 378–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Perez, M.; Ramirez, A.L.; Trujillo-ChiVacuán, E. An introduction to the special issue on the state of the art research on treatment and prevention of eating disorders on ethnic minorities. Eat. Disord. 2019, 27, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Striegel-Moore, R.H.; Rosselli, F.; Holtzman, N.; Dierker, L.; Becker, A.E.; Swaney, G. Behavioral symptoms of eating disorders in Native Americans: Results from the ADD Health Survey Wave III. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2011, 44, 561–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Middlemass, K.M.; Cruz, J.; Gamboa, A.; Johnson, C.; Taylor, B.; Gomez, F.; Becker, C.B. Food insecurity & dietary restraint in a diverse urban population. Eat. Disord. 2020, 29, 616–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coffino, J.A.; Grilo, C.M.; Udo, T. Childhood food neglect and adverse experiences associated with DSM-5 eating disorders in U.S. National Sample. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2020, 127, 75–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazzard, V.M.; Loth, K.A.; Hooper, L.; Becker, C.B. Food Insecurity and Eating Disorders: A Review of Emerging Evidence. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2020, 22, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNicholas, F.; O’Connor, C.; O’Hara, L.; McNamara, N. Stigma and treatment of eating disorders in Ireland: Healthcare professionals’ knowledge and attitudes. Ir. J. Psychol. Med. 2016, 33, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, S.B.; Pila, E.; Griffiths, S.; Le Grange, D. When illness severity and research dollars do not align: Are we overlooking eating disorders? World Psychiatry Off. J. World Psychiatr. Assoc. WPA 2017, 16, 321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Solmi, F.; Bould, H.; Lloyd, E.C.; Lewis, G. The shrouded visibility of eating disorders research. Lancet Psychiatry 2021, 8, 91–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsaffar, A.A. Sustainable diets: The interaction between food industry, nutrition, health and the environment. Food Sci. Technol. Int. 2016, 22, 102–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Just, D.R.; Payne, C.R. Obesity: Can behavioral economics help? Ann. Behav. Med. Publ. Soc. Behav. Med. 2009, 38 (Suppl. 1), S47–S55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, D.; Chaloupka, F.; Lindblom, E.N.; Sweanor, D.T.; O’Connor, R.J.; Shang, C.; Borland, R. The US Cigarette Industry: An Economic and Marketing Perspective. Tob. Regul. Sci. 2019, 5, 156–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mialon, M.; Ho, M.; Carriedo, A.; Ruskin, G.; Crosbie, E. Beyond nutrition and physical activity: Food industry shaping of the very principles of scientific integrity. Glob. Health 2021, 17, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nestle, M. Food company sponsorship of nutrition research and professional activities: A conflict of interest? Public Health Nutr. 2001, 4, 1015–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Rössner, S. Sugar in food—Nutrition or politics? The American sugar industry is offensive, children are the target. Lakartidningen 2004, 101, 1872. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Brownell, K.D.; Warner, K.E. The perils of ignoring history: Big Tobacco played dirty and millions died. How similar is Big Food? Milbank Q. 2009, 87, 259–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Monteiro, C.A. Nutrition and health. The issue is not food, nor nutrients, so much as processing. Public Health Nutr. 2009, 12, 729–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nguyen, K.H.; Glantz, S.A.; Palmer, C.N.; Schmidt, L.A. Tobacco industry involvement in children’s sugary drinks market. BMJ 2019, 364, l736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez, E.J. Getting to the root of the problem: The international and domestic politics of junk food industry regulation in Latin America. Health Policy Plan 2021, 36, 1521–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruch, H. Evolution of a Psychotherapeutic Approach to Eating Disorders: Obesity, Anorexia Nervosa, and the Person Within; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Becker, C.B.; Middlemass, K.M.; Gomez, F.; Martinez-Abrego, A. Eating Disorder Pathology Among Individuals Living with Food Insecurity: A Replication Study. Clin. Psychol. Sci. 2019, 7, 1144–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, K.A.; Forbush, K.T.; Richson, B.N.; Thomeczek, M.L.; Perko, V.L.; Bjorlie, K.; Christian, K.; Ayres, J.; Wildes, J.E.; Mildrum Chana, S. Food insecurity associated with elevated eating disorder symptoms, impairment, and eating disorder diagnoses in an American University student sample before and during the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2021, 54, 1213–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stinson, E.J.; Votruba, S.B.; Venti, C.; Perez, M.; Krakoff, J.; Gluck, M.E. Food Insecurity is Associated with Maladaptive Eating Behaviors and Objectively Measured Overeating. Obesity 2018, 26, 1841–1848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rasmusson, G.; Lydecker, J.A.; Coffino, J.A.; White, M.A.; Grilo, C.M. Household food insecurity is associated with binge-eating disorder and obesity. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2018, 52, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cossrow, N.; Pawaskar, M.; Witt, E.A.; Ming, E.E.; Victor, T.W.; Herman, B.K.; Wadden, T.A.; Erder, M.H. Estimating the Prevalence of Binge Eating Disorder in a Community Sample From the United States: Comparing DSM-IV-TR and DSM-5 Criteria. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2016, 77, e968–e974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Goode, R.W.; Cowell, M.M.; Mazzeo, S.E.; Cooper-Lewter, C.; Forte, A.; Olayia, O.I.; Bulik, C.M. Binge eating and binge-eating disorder in Black women: A systematic review. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2020, 53, 491–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagata, J.M.; Ganson, K.T.; Austin, S.B. Emerging trends in eating disorders among sexual and gender minorities. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2020, 33, 562–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamody, R.C.; Grilo, C.M.; Udo, T. Disparities in DSM-5 defined eating disorders by sexual orientation among U.S. adults. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2020, 53, 278–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazzard, V.M.; Barry, M.R.; Leung, C.W.; Sonneville, K.R.; Wonderlich, S.A.; Crosby, R.D. Food insecurity and its associations with bulimic-spectrum eating disorders, mood disorders, and anxiety disorders in a nationally representative sample of U.S. adults. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2021, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puhl, R.M.; Brownell, K.D. Confronting and coping with weight stigma: An investigation of overweight and obese adults. Obesity 2006, 14, 1802–1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomiyama, A.J. Weight stigma is stressful. A review of evidence for the Cyclic Obesity/Weight-Based Stigma model. Appetite 2014, 82, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Puhl, R.; Suh, Y. Stigma and eating and weight disorders. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2015, 17, 552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puhl, R.; Suh, Y. Health Consequences of Weight Stigma: Implications for Obesity Prevention and Treatment. Curr. Obes. Rep. 2015, 4, 182–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vartanian, L.R.; Porter, A.M. Weight stigma and eating behavior: A review of the literature. Appetite 2016, 102, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doley, J.R.; Hart, L.M.; Stukas, A.A.; Petrovic, K.; Bouguettaya, A.; Paxton, S.J. Interventions to reduce the stigma of eating disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2017, 50, 210–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reas, D.L. Public and Healthcare Professionals’ Knowledge and Attitudes toward Binge Eating Disorder: A Narrative Review. Nutrients 2017, 9, 1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Tomiyama, A.J.; Carr, D.; Granberg, E.M.; Major, B.; Robinson, E.; Sutin, A.R.; Brewis, A. How and why weight stigma drives the obesity ‘epidemic’ and harms health. BMC Med. 2018, 16, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahorsu, D.K.; Lin, C.Y.; Imani, V.; Griffiths, M.D.; Su, J.A.; Latner, J.D.; Marshall, R.D.; Pakpour, A.H. A prospective study on the link between weight-related self-stigma and binge eating: Role of food addiction and psychological distress. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2020, 53, 442–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puhl, R.M.; Lessard, L.M.; Larson, N.; Eisenberg, M.E.; Neumark-Stzainer, D. Weight Stigma as a Predictor of Distress and Maladaptive Eating Behaviors During COVID-19: Longitudinal Findings From the EAT Study. Ann. Behav. Med. Publ. Soc. Behav. Med. 2020, 54, 738–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hollett, K.B.; Carter, J.C. Separating binge-eating disorder stigma and weight stigma: A vignette study. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2021, 54, 755–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mountford, V.; Corstorphine, E.; Tomlinson, S.; Waller, G. Development of a measure to assess invalidating childhood environments in the eating disorders. Eat. Behav. 2007, 8, 48–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haslam, M.; Mountford, V.; Meyer, C.; Waller, G. Invalidating childhood environments in anorexia and bulimia nervosa. Eat. Behav. 2008, 9, 313–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caslini, M.; Bartoli, F.; Crocamo, C.; Dakanalis, A.; Clerici, M.; Carrà, G. Disentangling the Association Between Child Abuse and Eating Disorders: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Psychosom. Med. 2016, 78, 79–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuthbert, K.; Hardin, S.; Zelkowitz, R.; Mitchell, K. Eating Disorders and Overweight/Obesity in Veterans: Prevalence, Risk Factors, and Treatment Considerations. Curr. Obes. Rep. 2020, 9, 98–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grogan, K.; MacGarry, D.; Bramham, J.; Scriven, M.; Maher, C.; Fitzgerald, A. Family-related non-abuse adverse life experiences occurring for adults diagnosed with eating disorders: A systematic review. J. Eat. Disord. 2020, 8, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molendijk, M.L.; Hoek, H.W.; Brewerton, T.D.; Elzinga, B.M. Childhood maltreatment and eating disorder pathology: A systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis. Psychol. Med. 2017, 47, 1402–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmisano, G.L.; Innamorati, M.; Vanderlinden, J. Life adverse experiences in relation with obesity and binge eating disorder: A systematic review. J. Behav. Addict. 2016, 5, 11–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Amianto, F.; Spalatro, A.V.; Rainis, M.; Andriulli, C.; Lavagnino, L.; Abbate-Daga, G.; Fassino, S. Childhood emotional abuse and neglect in obese patients with and without binge eating disorder: Personality and psychopathology correlates in adulthood. Psychiatry Res. 2018, 269, 692–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belli, H.; Ural, C.; Akbudak, M.; Sagaltıcı, E. Levels of childhood traumatic experiences and dissociative symptoms in extremely obese patients with and without binge eating disorder. Nord. J. Psychiatry 2019, 73, 527–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borg, S.L.; Schaefer, L.M.; Hazzard, V.M.; Herting, N.; Peterson, C.B.; Crosby, R.D.; Crow, S.J.; Engel, S.G.; Wonderlich, S.A. Relationships Between Childhood Abuse and Eating Pathology Among Individuals with Binge-Eating Disorder: Examining the Moderating Roles of Self-Discrepancy and Self-Directed Style. Eat. Disord. 2021, 127, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, J.; El-Gabalawy, R.; Sommer, J.L.; Pietrzak, R.H.; Mitchell, K.; Mota, N. Trauma Exposure, DSM-5 Posttraumatic Stress, and Binge Eating Symptoms: Results From a Nationally Representative Sample. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2019, 80, 19m12813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meneguzzo, P.; Cazzola, C.; Castegnaro, R.; Buscaglia, F.; Bucci, E.; Pillan, A.; Garolla, A.; Bonello, E.; Todisco, P. Associations Between Trauma, Early Maladaptive Schemas, Personality Traits, and Clinical Severity in Eating Disorder Patients: A Clinical Presentation and Mediation Analysis. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 661924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, K.S.; Scioli, E.R.; Galovski, T.; Belfer, P.L.; Cooper, Z. Posttraumatic stress disorder and eating disorders: Maintaining mechanisms and treatment targets. Eat. Disord. 2021, 29, 292–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteleone, A.M.; Cascino, G.; Pellegrino, F.; Ruzzi, V.; Patriciello, G.; Marone, L.; De Felice, G.; Monteleone, P.; Maj, M. The association between childhood maltreatment and eating disorder psychopathology: A mixed-model investigation. Eur. Psychiatry 2019, 61, 111–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteleone, A.M.; Tzischinsky, O.; Cascino, G.; Alon, S.; Pellegrino, F.; Ruzzi, V.; Latzer, Y. The connection between childhood maltreatment and eating disorder psychopathology: A network analysis study in people with bulimia nervosa and with binge eating disorder. Eat. Weight Disord. EWD 2021, 27, 253–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanzhula, I.A.; Calebs, B.; Fewell, L.; Levinson, C.A. Illness pathways between eating disorder and post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms: Understanding comorbidity with network analysis. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. J. Eat. Disord. Assoc. 2019, 27, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidaña, A.G.; Forbush, K.T.; Barnhart, E.L.; Mildrum Chana, S.; Chapa, D.A.N.; Richson, B.; Thomeczek, M.L. Impact of trauma in childhood and adulthood on eating-disorder symptoms. Eat. Behav. 2020, 39, 101426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javaras, K.N.; Pope, H.G.; Lalonde, J.K.; Roberts, J.L.; Nillni, Y.I.; Laird, N.M.; Bulik, C.M.; Crow, S.J.; McElroy, S.L.; Walsh, B.T.; et al. Co-occurrence of binge eating disorder with psychiatric and medical disorders. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2008, 69, 266–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felitti, V.J.; Anda, R.F.; Nordenberg, D.; Williamson, D.F.; Spitz, A.M.; Edwards, V.; Koss, M.P.; Marks, J.S. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. Am. J. Prev. Med. 1998, 14, 245–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, D.F.; Thompson, T.J.; Anda, R.F.; Dietz, W.H.; Felitti, V. Body weight and obesity in adults and self-reported abuse in childhood. Int. J. Obes. Relat. Metab. Disord. 2002, 26, 1075–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Da Luz, F.Q.; Sainsbury, A.; Mannan, H.; Touyz, S.; Mitchison, D.; Girosi, F.; Hay, P. An investigation of relationships between disordered eating behaviors, weight/shape overvaluation and mood in the general population. Appetite 2018, 129, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Da Luz, F.Q.; Hay, P.; Touyz, S.; Sainsbury, A. Obesity with Comorbid Eating Disorders: Associated Health Risks and Treatment Approaches. Nutrients 2018, 10, 829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hovell, M.F.; Koch, A.; Hofstetter, C.R.; Sipan, C.; Faucher, P.; Dellinger, A.; Borok, G.; Forsythe, A.; Felitti, V.J. Long-term weight loss maintenance: Assessment of a behavioral and supplemented fasting regimen. Am. J. Public Health 1988, 78, 663–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Felitti, V.J. Origins of the ACE Study. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2019, 56, 787–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Felitti, V.J. Childhood sexual abuse, depression, and family dysfunction in adult obese patients: A case control study. South Med. J. 1993, 86, 732–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talmon, A.; Widom, C.S. Childhood Maltreatment and Eating Disorders: A Prospective Investigation. Child Maltreatment 2022, 27, 88–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widom, C.S. Are Retrospective Self-reports Accurate Representations or Existential Recollections? JAMA Psychiatry 2019, 76, 567–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soanes, C.; Hawker, S. (Eds.) Interpersonal. In Compact Oxford English Dictionary, 3rd ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ivanova, I.V.; Tasca, G.A.; Proulx, G.; Bissasda, H. Contribution of Interpersonal Problems to Eating Disorder Psychopathology via Negative Affect in Treatment-seeking Men and Women: Testing the Validity of the Interpersonal Model in an Understudied Population. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 2017, 24, 952–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chyurlia, L.; Tasca, G.A.; Bissada, H. An Integrative Approach to Clinical Decision-Making for Treating Patients With Binge-Eating Disorder. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 2573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brugnera, A.; Carlucci, S.; Compare, A.; Tasca, G.A. Persistence of friendly and submissive interpersonal styles among those with binge-eating disorder: Comparisons with matched controls and outcomes after group therapy. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 2019, 26, 603–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brugnera, A.; Lo Coco, G.; Salerno, L.; Sutton, R.; Gullo, S.; Compare, A.; Tasca, G.A. Patients with Binge Eating Disorder and Obesity have qualitatively different interpersonal characteristics: Results from an Interpersonal Circumplex study. Compr. Psychiatry 2018, 85, 36–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Luo, X.; Nuttall, A.K.; Locke, K.D.; Hopwood, C.J. Dynamic longitudinal relations between binge eating symptoms and severity and style of interpersonal problems. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2018, 127, 30–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, N.L.; Higgins Neyland, M.K.; Young, J.F.; Wilfley, D.E.; Tanofsky-Kraff, M. Interpersonal psychotherapy for the prevention of binge-eating disorder and adult obesity in an African American adolescent military dependent boy. Eat. Behav. 2020, 38, 101408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, M.E.; Tasca, G.A.; Ritchie, K.; Balfour, L.; Maxwell, H.; Bissada, H. Interpersonal learning is associated with improved self-esteem in group psychotherapy for women with binge eating disorder. Psychotherapy 2014, 51, 66–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grilo, C.M. Psychological and Behavioral Treatments for Binge-Eating Disorder. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2017, 78 (Suppl. 1), 20–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miniati, M.; Callari, A.; Maglio, A.; Calugi, S. Interpersonal psychotherapy for eating disorders: Current perspectives. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2018, 11, 353–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Karam, A.M.; Fitzsimmons-Craft, E.E.; Tanofsky-Kraff, M.; Wilfley, D.E. Interpersonal Psychotherapy and the Treatment of Eating Disorders. Psychiatr. Clin. N. Am. 2019, 42, 205–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karam, A.M.; Eichen, D.M.; Fitzsimmons-Craft, E.E.; Wilfley, D.E. An examination of the interpersonal model of binge eating over the course of treatment. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. J. Eat. Disord. Assoc. 2020, 28, 66–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, G.; Oh, J.; Jung, I.C. Depression and physical health as serial mediators between interpersonal problems and binge-eating behavior among hospital nurses in South Korea. Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2021, 35, 250–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambwani, S.; Roche, M.J.; Minnick, A.M.; Pincus, A.L. Negative affect, interpersonal perception, and binge eating behavior: An experience sampling study. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2015, 48, 715–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, C.; Serpell, L.; Waller, G.; Murphy, F.; Treasure, J.; Leung, N. Cognitive avoidance in the strategic processing of ego threats among eating-disordered patients. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2005, 38, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanakam, N.; Krug, I.; Raoult, C.; Collier, D.; Treasure, J. Social and emotional processing as a behavioural endophenotype in eating disorders: A pilot investigation in twins. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. J. Eat. Disord. Assoc. 2013, 21, 294–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardi, V.; Di Matteo, R.; Gilbert, P.; Treasure, J. Rank perception and self-evaluation in eating disorders. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2014, 47, 543–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardi, V.; Tchanturia, K.; Treasure, J. Premorbid and Illness-related Social Difficulties in Eating Disorders: An Overview of the Literature and Treatment Developments. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2018, 16, 1122–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilon Mann, T.; Hamdan, S.; Bar-Haim, Y.; Lazarov, A.; Enoch-Levy, A.; Dubnov-Raz, G.; Treasure, J.; Stein, D. Different attention bias patterns in anorexia nervosa restricting and binge/purge types. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. J. Eat. Disord. Assoc. 2018, 26, 293–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leppanen, J.; Ng, K.W.; Kim, Y.R.; Tchanturia, K.; Treasure, J. Meta-analytic review of the effects of a single dose of intranasal oxytocin on threat processing in humans. J. Affect. Disord. 2018, 225, 167–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Schell, S.E.; Banica, I.; Weinberg, A.; Racine, S.E. Hunger games: Associations between core eating disorder symptoms and responses to rejection by peers during competition. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2021, 54, 802–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stojek, M.; Shank, L.M.; Vannucci, A.; Bongiorno, D.M.; Nelson, E.E.; Waters, A.J.; Engel, S.G.; Boutelle, K.N.; Pine, D.S.; Yanovski, J.A.; et al. A systematic review of attentional biases in disorders involving binge eating. Appetite 2018, 123, 367–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brownstone, L.M.; Bardone-Cone, A.M. Subjective binge eating: A marker of disordered eating and broader psychological distress. Eat. Weight Disord. EWD 2021, 26, 2201–2209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodrick, G.K.; Pendleton, V.R.; Kimball, K.T.; Carlos Poston, W.S.; Reeves, R.S.; Foreyt, J.P. Binge eating severity, self-concept, dieting self-efficacy and social support during treatment of binge eating disorder. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 1999, 26, 295–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, T.B.; Lewis, R.J. Examining social support, rumination, and optimism in relation to binge eating among Caucasian and African-American college women. Eat. Weight Disord. EWD 2017, 22, 693–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, R.; Zhang, M.; Oakman, J.M.; Wang, J.; Zhu, S.; Zhao, C.; Hu, Z.; Buchanan, N.T. Eating disorders treatment experiences and social support: Perspectives from service seekers in mainland China. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2021, 54, 1537–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagata, J.M.; Iyer, P.; Chu, J.; Baker, F.C.; Pettee Gabriel, K.; Garber, A.K.; Murray, S.B.; Bibbins-Domingo, K.; Ganson, K.T. Contemporary screen time modalities among children 9–10 years old and binge-eating disorder at one-year follow-up: A prospective cohort study. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2021, 54, 887–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lonergan, A.R.; Bussey, K.; Fardouly, J.; Griffiths, S.; Murray, S.B.; Hay, P.; Mond, J.; Trompeter, N.; Mitchison, D. Protect me from my selfie: Examining the association between photo-based social media behaviors and self-reported eating disorders in adolescence. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2020, 53, 485–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.R.; Mackert, M. Social media use and binge eating: An integrative review. Public Health Nurs. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morant, H. BMA demands more responsible media attitude on body image. BMJ 2000, 320, 1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Giordano, S. Eating disorders and the media. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2015, 28, 478–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- British Medical Association. Eating Disorders, Body Image and the Media; BMJ Books: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Frank, G.K. Advances from neuroimaging studies in eating disorders. CNS Spectr. 2015, 20, 391–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, G.K.W. Neuroimaging and eating disorders. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2019, 32, 478–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, G.K.; Bailer, U.F.; Henry, S.; Wagner, A.; Kaye, W.H. Neuroimaging studies in eating disorders. CNS Spectr. 2004, 9, 539–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewer, M.; Bauer, A.; Hartmann, A.S.; Vocks, S. Different Facets of Body Image Disturbance in Binge Eating Disorder: A Review. Nutrients 2017, 9, 1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nutley, S.K.; Falise, A.M.; Henderson, R.; Apostolou, V.; Mathews, C.A.; Striley, C.W. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Disordered Eating Behavior: Qualitative Analysis of Social Media Posts. JMIR Ment. Health 2021, 8, e26011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lydecker, J.A.; Grilo, C.M. Different yet similar: Examining race and ethnicity in treatment-seeking adults with binge eating disorder. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2016, 84, 88–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| I. Eligibility criteria for researchers (18 recruited, 7 enrolled) |

| Eligibility criteria for researchers required meeting one of the following four criteria (I.1–4): |

|

|

|

|

| II. Eligibility criteria for clinicians and healthcare administrators (18 recruited, 6 enrolled) |

| Eligibility for clinicians and healthcare administrators required meeting ≥3 of the following 8 criteria: |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| III. Additional Eligibility Criteria (2 recruited, 2 enrolledb |

| In addition to the academic/research and clinical criteria above, individuals who met ≥1 academic/research criterion (I.1–4) and ≥1 clinical criteria (II.1–8) were also eligible. |

| Question | n asked (n/14) |

| Please describe your perspective on (or knowledge of) literature and research findings, current clinical guidelines, and your own personal experiences that relate to binge eating disorder pathology and treatment. | 14 (100%) |

| How do you view the disease process in relation to the following possible aspects, and how important is it for treatment interventions to address these aspects (if at all)? | |

| Physical/Biological Cognitive/mental Emotional Spiritual Economic Social Cultural Other | 14 (100%) 14 (100%) 14 (100%) 14 (100%) 11 (79%) 12 (86%) 12 (86%) 14 (100%) |

| How do you view the disease process in relation to the following possible aspects, and how important is it for treatment interventions to address these aspects (if at all)? | |

| Physical/Biological Cognitive/mental Emotional Spiritual Economic Social Cultural Other | 14 (100%) 14 (100%) 14 (100%) 14 (100%) 11 (79%) 12 (86%) 12 (86%) 14 (100%) |

| Please describe your view on the following health factors as they relate to adult binge eating disorder pathology and treatment: | |

| Weight Stigma Malnutrition/Undernutrition Sleep Early Life Trauma/post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) Coronavirus-19 (COVID-19)/Quarantine Other | 9 (64%) 10 (71%) 11 (79%) 9 (64%) 10 (71%) 12 (86%) |

| Are there any other aspects of binge eating disorder pathology that you feel are important to address or discuss (that have not been addressed above)? | 12 (86%) |

| Please describe your perspective on current research gaps that exist in the field of binge eating disorder. | 14 (100%) |

| Do you have any other suggestions that relate to future research on binge eating disorder? | 14 (100%) |

| Accreditations | |

| Fellow of the Academy of Eating Disorders (FAED) | 8 (62%) |

| Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) or Science (ScD) | 8 (62%) |

| Medical Doctor (MD) | 4 (31%) |

| Licensed or Registered Dietician (LD/RD) or Registered Dieticians Certified in Eating Disorders (CEDRD) | 4 (31%) |

| Healthcare Administrator | 2 (15%) |

| Certified Chef | 1 (8%) |

| Certified Intuitive Eating Specialist (CIES) | 1 (8%) |

| Fellow of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology (FACNP) | 1 (8%) |

| Bachelor of Medicine Chirurgical Doctor (Bachelor of Surgery) (B\MBChB) | 1 (8%) |

| Master’s in Public Health (MPH) | 1 (8%) |

| Sex (at birth) | |

| Female | 8 (62%) |

| Male | 5 (38%) |

| Other | 0 (0%) |

| Age | |

| 55 ± 10.2 years (range: 37–44 yrs., n = 13) | |

| Ethnicity | |

| Hispanic or Latino | 0 (0%) |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 13 (100%) |

| Race | |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 0 (0%) |

| Asian | 1 (8%) |

| Black or African American | 0 (0%) |

| Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander | 0 (0%) |

| White | 12 (92%) |

| More than one race | 0 (0%) |

| Geographical location of residence | 7 reported |

| United States of America (USA) | 5 (71%) ** |

| United Kingdom (UK) | 1 (14%) ** |

| Australia (AU) | 1 (14%) ** |

| Canada (CA) | 1 (14%) ** |

| Eligibility criteria met: | |

| Research/Academic | 6 (43%) |

| Clinical/Administrative | 5 (36%) |

| Both (Research/Academic AND Clinical/Administrative) | 1 (7%) |

| Combined (≥1 Research/Academic and ≥1 Clinical Administrative) | 2 (14%) |

| Identified Systems of Oppression that Relate to BED Pathology | 14 (100%) |

| Systematic discrimination | 12 (82%) |

| Body weight/shape/size discrimination (see Theme 4) | 12 (82%) |

| Structural racism | 2 (14%) |

| Structural sexism | 1 (7%) |

| Media messaging and sociocultural ideals/mandates (see Themes 4 and 7) | 12 (82%) |

| Perpetuating stigmatization | 12 (82%) |

| Body weight/shape/size ideals (and discrimination) | 12 (82%) |

| “Diet culture” | 3 (21%) |

| Movement & fitness ideals | 2 (14%) |

| Insurance and healthcare systems | 9 (64%) |

| Insurance costs and coverage | 6 (43%) |

| Treatment costs | 6 (43%) |

| Systematic stigmatization from healthcare providers | 6 (43%) |

| Geographical access to treatment resources | 4 (29%) |

| Mandated movement for individuals in larger bodies | 2 (14%) |

| Provider scarcity | 1 (7%) |

| “Predatory” food industries/environment (see Section Theme 8) | 4 (29%) |

| Abuse (sexual, emotional, or physical) | 4 (29%) |

| Geographical systems 1 | 4 (29%) |

| ) Eating disorder research as a field 2 | 3 (21%) |

| ) Eating disorder research funding 3 | 2 (14%) |

| Economic exploitation 4 | 1 (7%) |

| School systems | 1 (7%) |

| Legal systems | 1 (7%) |

| Police harassment | 1 (7%) |

| Additional participant statements regarding systems of oppression: | |

| “In [my country], there is no public funding for people who have binge eating disorder. …they’re just sort of on their own when it comes to treatment.” (P38) | |

| “…the food industry … there’s all these food scientists and psychologists that go work for this industry to figure out how to generate food that is the most profitable and the hardest to not overeat. …there are companies and individuals profiting off of making food that will lead someone down a path to binge eating disorder or binge eating… If that’s not a system of oppression I don’t know what is.” (P16) | |

| “There’s so much less research on binge eating disorder than [on] anorexia nervosa or bulimia nervosa … how it’s experienced across different communities, how intersectional systems of oppression affect risk of developing it…” (P16) “How we think about eating disorders is that … anorexia was kind of the granddaddy, … the thing we knew first, and then bulimia kind of grew out of that next, and … people used to refer to [it] as … failed anorexia… … And I would say, in part that, … binge eating disorder… was … thought of … Initially [as being] like bulimia, but without the purging …so [the] same mechanisms… …[and] I would say traditionally, when I’m talking to my colleagues in the eating disorder field… the dominant mechanisms that … have a tendency to be most thought of are things like restraint and shape and weight overvaluations but there’s starting to be a bigger push to … have a more encompassing view on mechanisms like reward and inhibitory control and emotion, distraction, things like that.” “… I think in part because the restraint stuff wasn’t necessarily panning out with binge eating disorder quite as well.” (P19) | |

| “I think binge eating disorder is in a little bit of a strange place in the United States. Because NIH you have mental health conditions in one place at NIMH, and you have metabolic conditions at another place at NIDDK. And sometimes I think binge eating disorder doesn’t have a home. So how many RCTs have been funded by the NIH in the treatment of binge eating disorder? … I think that there’s a professional socio-cultural administrative framework that is having trouble getting its arms around binge eating disorder…” (P33) | |

| “[I am] constantly surprised at how easy it is to get money for [weight disorders in comparison to eating disorders]. The weight loss trial, not hard at all [to get funded]. If you think you’ve got the diet that works, it’s not hard to persuade governments or philanthropists or people to fund you. It’s very hard to persuade governments or philanthropists to fund if we think we’ve got some new eating disorder treatment, or some enhancement of initial treatment, we find it much harder to get [funding for] than yet another diet.” (P93) “Systems of oppression, which actually work through [many] domains [e.g., emotional, spiritual, economic, social, and cultural]… if you think about structural racism or … structural sexism or economic exploitation or there’s all these kinds of systems, they might be legal systems or economic systems that will increase risk for different kinds of conditions and certainly binge eating disorder is affected by all of this—discrimination, housing precarity, economic precarity, all of these the way these systems will affect people and families and communities… … …how structural racism might set people up on a path to end up facing food insecurity or nutrition insecurity … schools failing young people, maybe somebody doesn’t get their degree or [has] other things going on in their communities where they’re being harassed by police … or they’re being abused and nobody’s watching [or] nobody’s there to protect them. There are so many levels of ways that systems are failing people—particularly in children [and] particularly in communities that are marginalized—that then create ACES [adverse childhood experiences] … that could increase the risk of binge eating disorder.” (P16) | |

| Marginalized & under-Represented Populations | 14 (100%) |

| Low socio-economic status/economic insecurity (see Theme 3.i) | 13 (93%) |

| Food or nutrition scarcity (see Theme 3.ii–iii) | 10 (71%) |

| Male sex/gender | 8 (57%) |

| Racial and ethnic minorities (e.g., BIPOC) | 5 (36%) |

| Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender, queer (LGBTQ) & nonbinary | 3 (21%) |

| Age | 2 (14%) |

| Religion | 1 (7%) |

| Additional participant statements on minority- and marginalized populations | |

| “The number of people that I’ve seen and done evaluations on [who] are really surprised to learn that the way that they’ve been eating is actually considered disordered, and that they have an eating disorder, and I think that that’s especially true for men, I think that’s especially true for any individuals [who] don’t fit that stereotypical mold of who has an eating disorder. …We know that unfortunately eating disorders have been hampered by these old stereotypes about who’s affected, and that leaves millions of people undetected with an eating disorder. …There’s a lot of emphasis these days on making sure that we’re meeting the needs of underrepresented groups and so a lot of people are talking about how eating disorders don’t discriminate, and that’s certainly true, and I think it also makes sense to talk about the specific ways in which underrepresented groups might be struggling that are unique to them and their experiences versus just saying ‘anyone can be affected.” (P75) | |

| “So much of the eating disorder perspectives and history … that we attend to are very female-focused, … and come out of … the female gender orientation. …I think anorexia [nervosa] kind of set the stage [for a current understanding of eating disorder pathology and treatment], [and anorexia nervosa] is so dominantly female.” (P16) | |

| “Certainly, there has been discussion in the eating disorder world … about whether different ethnicities have different levels of acceptance of overweight and obesity. So, one wonders whether that has impacts on … the frequency of the distress about binge eating disorder or the wish for treatment.” (P46) | |

| Subtheme (i) Economic Aspects of Binge Eating Disorder | 13 (93%) |

| Direct connections between BED pathology and economic status/precarity | 5 (36%) |

| Potential mediators and moderators of relationship between economic status/precarity and BED pathology | 9 (64%) |

| Food insecurity | 5 (36%) |

| Nutritional access/insecurity | 5 (36%) |

| Food environment | 3 (21%) |

| Mental health risks | 2 (14%) |

| COVID-19 pandemic | 2 (14%) |

| Access to treatment resources | 2 (14%) |

| Weight biases & descrimination 1 | 1 (7%) |

| Subtheme (ii) Topics related to food insecurity & scarcity: | 9 (64%) |

| Potentially disrupting one’s relationship with food or eating | 5 (36%) |

| Linked to economic insecurity | 5 (36%) |

| Cited research findings linking food insecurity to BED 3 | 5 (36%) |

| Increasing risk for other physical and psychological health problems | 4 (29%) |

| Linked to the COVID-19 pandemic | 2 (14%) |

| Childhood adverse food experiences as important ACEs 2 | 1 (7%) |

| Subtheme (iii) Topics related to nutrition scarcity: | 6 (43%) |

| Linked to lower socioeconomic status | 4 (29%) |

| Linked to food environment | 3 (21%) |

| Cited research findings linking nutrition scarcity to binge eating and obesity4 | 1 (7%) |

| Cited research relating urbanization factors to increased risk for BED5 | 1 (7%) |

| Additional participant statements regarding economic insecurity: | |

| “The big thing about economics and binge eating disorder is that horrible availability of foods. [The foods that are accessible to lower income individuals] are really … great binge foods. They’re not great nutritional foods. … I can buy a half dozen quarter-pounders for what it might cost to get a decent meal. [so] …it’s not that big [of] a surprise that if I haven’t got the money, I go and buy a couple of quarter-pounders rather than trying to pay for a meal that I can’t pay for…” (P84) | |

| “If you have less money, if you know lower socioeconomic status, then you are maybe forced to eat less good food, less healthy food, maybe food with… less good fat content [and] that then could…—if you have a biological vulnerability—change your brain more than somebody else who eats healthier, and that then might … flip the switch to then engage more in [binge eating] behaviors…” (P53) | |

| Additional participant statements regarding food insecurity: | |

| “Recent data have come out between 2017 and 2020 around food insecurity, and the higher rates of [binge eating disorder] among people with food insecurity [but] we as a field, I don’t think, have paid enough attention to food insecurity [or] screening for food insecurity [or] addressing it in our client population, much less talking to the food insecurity world about addressing binge eating disorder, in particular among people with food insecurity.” (P60) “Access to food is a big, big deal. …In households where there’s …food scarcity, [that] can lead to binge eating. You don’t know when you’re getting your next meal? And it’s in front of you? And you’re really, really, really hungry because you haven’t eaten in a while. And then there’s food around? What do any of us do when we’re really hungry? We eat.” (P7) | |

| “You can’t underestimate the impact of [food insecurity] on somebody’s eating disorder. If [an individual has] food insecurity [gets] a lump sum of financial resources or food resource over a period of time and that’s supposed to last them over a week or a month, and they have binge eating disorder, it’s not unlikely that a significant portion of that food may be consumed and then they don’t have resources to buy more. And so now we have somebody who’s managing a binge with the financial constraint, which may likely add to the guilt of that eating disorder behavior and feel like it’s all their fault, [which can lead] back to the sort of cognitive thoughts [of], ‘I’ll never be able to do this. This is all my fault. I have no willpower. I’m a terrible person. How come I can’t do this?’ So, I think economically, we really have to pay attention to the impact of economic status, but particularly around food insecurity. And when you look at the data on financial hardship, food insecurity is often the highest ranked area of struggle, right? There’s housing, there’s medical, there’s utility, and then there’s food and food is the one that people express most frequently struggling with when they have financial hardship.” (P60) | |

| Additional participant statements regarding nutrition scarcity: | |

| “We have … whole … city areas that are geared up around fast food. … [there are places where you can] very easily get a hold of fast food. You [can’t] very easily get a hold of decent food.” (P84) | |

| “[Undernutrition] is an aspect of any eating disorder because even in binge eating disorder, you’re going to find people with malnutrition. Malnutrition doesn’t discriminate. [There is] research on malnutrition [showing that] a lot [of individuals with malnutrition] [are] in a larger body. So that aspect, we know that malnutrition can affect our food preoccupation.” (P37) | |

| Subtheme (i) Forms of Stigmatization Recognized as Relevant to BED | 13 (93%) |

| Body weight/shape/size stigmatization and discrimination | 12 (82%) |

| Eating disorder diagnosis stigmatization | 5 (36%) |

| Mental health diagnosis stigmatization | 5 (36%) |

| Any medical diagnosis stigmatization | 1 (7%) |

| Stigmatization around perfectionistic food/eating ideals | 1 (7%) |

| These stigmatizations suggested as having higher prevalence in specific populations1 | 2 (14%) |

| Subtheme (ii) Body weight/shape/size stigmatization described as: | 5 (36%) |

| Potentially exacerbating BED symptoms and severity | 11 (79%) |

| Prevalent among healthcare providers and in the medical system | 6 (43%) |

| Core to BED pathology | 4 (29%) |

| Area requiring better understanding of its trajectory and impact | 4 (29%) |

| Traumatic 2 | 3 (21%) |

| Possibly varying by ethnicity 3 | 1 (7%) |

| Additional participant statements regarding body weight/shape/size stigmatization and discrimination: | |

| “…If the eating disorder has been associated with weight gain, then we know for a fact that they’ve been intruded upon by families, doctors … institutions, and… there’s trauma associated with that… with… being told day in and day out that what you are is not acceptable or lovable or okay,” … “many people who are living in larger bodies have been teased or bullied around weight, so there’s a lot of trauma associated binge eating disorder…” (P7) | |

| “If you make a comment about somebody’s race in the middle of an airplane, as you’re getting seated …probably a bunch of people are going to [tell you] how hurtful and how unquestionably not okay that behavior is. But if you’re on that same airplane and somebody makes a comment about your weight, most people aren’t going to notice, and that’s just not okay.” (P60) | |

| “Weight discrimination is legal almost everywhere in this country. … You could be fired. …based on your weight … and you have no recourse. … It’s not a protected status and it happens everywhere. …There’s research also on getting admitted to college. So that’s a similar process of applying for a job in the way people apply for college but it’s about access to higher education and there’s research showing weight discrimination comes in there.” (P16) | |

| Subtheme (i) Relevant Forms of Trauma/Adversity | 7 (50%) |

| Abuse (sexual, emotional, or physical) | 4 (29%) |

| Early childhood abuse | 2 (14%) |

| Body weight/shape/size stigmatization | 3 (21%) |

| COVID-19 pandemic | 3 (21%) |

| Invalidating/oppressive experiences/environments | 2 (14%) |

| Interpersonal trauma | 2 (14%) |

| Mandated movement or physical activity1 | 2 (14%) |

| Childhood of food scarcity/insecurity as ACES | 1 (7%) |

| Chronic dieting | 1 (7%) |

| Untreated diagnoses (e.g., ADHD) | 1 (7%) |

| Impacts of IBS | 1 (7%) |

| Trauma related to self-neglect and negative views on self-care2 | 1 (7%) |

| Subtheme (ii) Relationship between trauma/adversity & BED | 11 (79%) |

| Trauma/adversity as relevant to BED psychopathology | 11 (79%) |

| Trauma/adversity highly relevant for a minority with that comorbidity | 1 (7%) |

| Trauma/adversity as increasing risk for BED | 5 (36) |

| Cited research findings | 2 (14%) |

| ACES can result in PTSD and BED | 2 (14%) |

| Trauma/adversity increase risk for m[any] psychiatric problems | 2 (14%) |

| Trauma/adversity often precede BED (not vice versa) | 1 (7%) |

| Childhood (but not adult) trauma/adversity as risk factor | 1 (7%) |

| PTSD highly comorbid with BED and food addiction | 1 (7%) |

| Neurobiological impacts of trauma/adversity may prime BED | 2 (14%) |

| Negative impact on self-regulation | 1 (7%) |

| Binge eating to cope with trauma/adversity3 | 2 (14%) |

| Trauma/adversity as exacerbate BED symptoms | 2 (14%) |

| Additional possible mechanistic pathways | 2 (14%) |