Parental Bonding and Relationships with Friends and Siblings in Adolescents with Depression

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Patients

2.3. Instruments

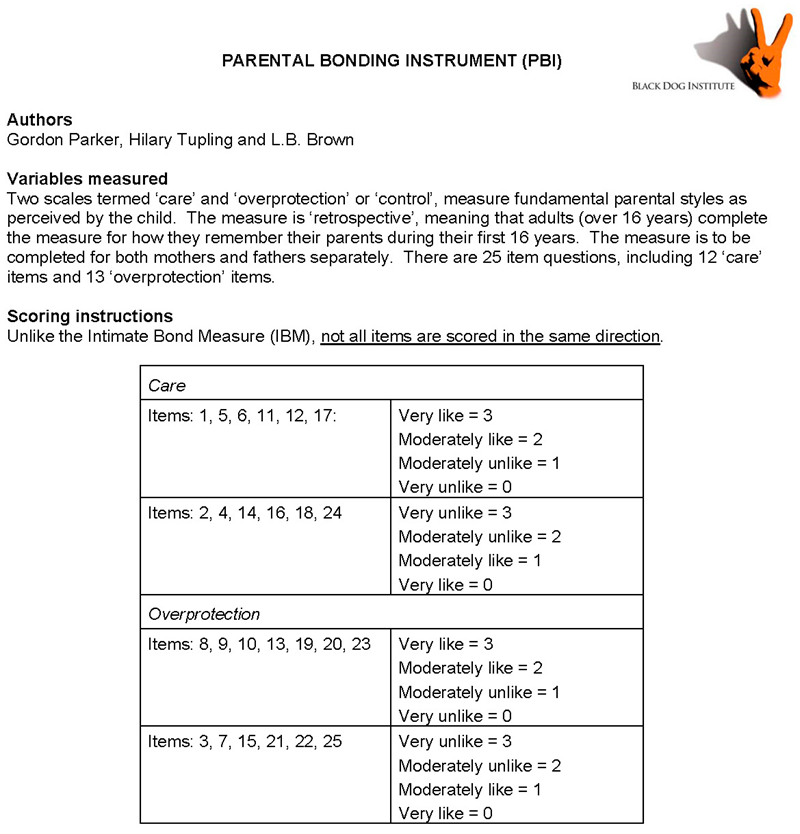

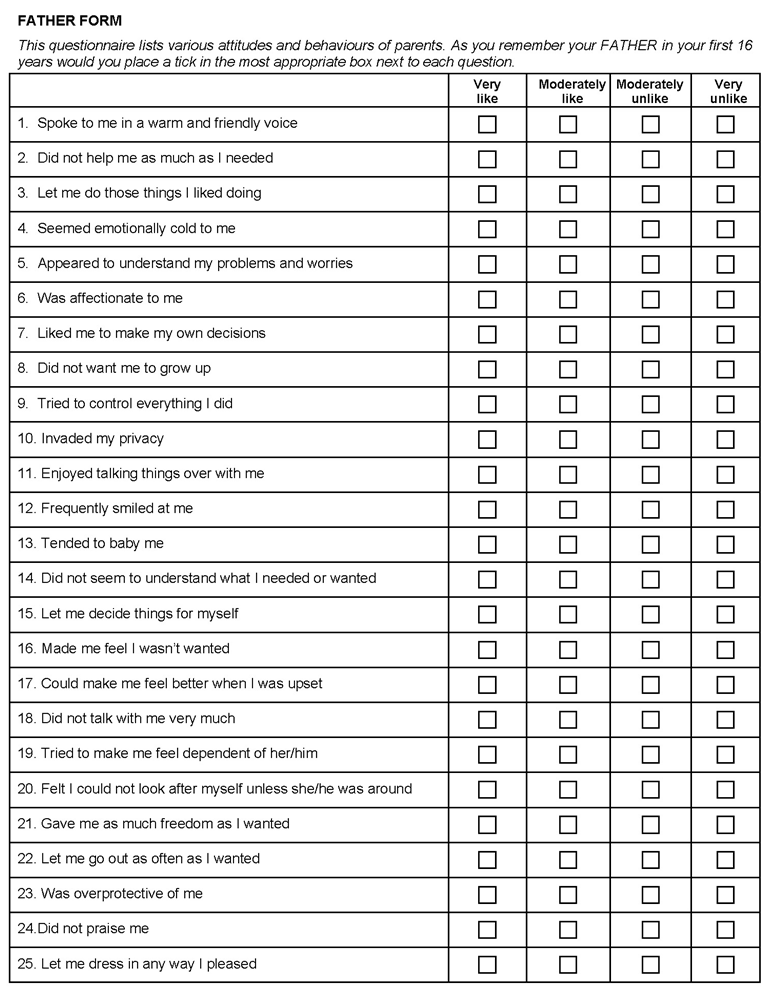

2.3.1. The Parental Bonding Instrument

2.3.2. The Adolescent Relationships Scale

2.4. Procedure

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

Limitations of the Study

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix B

References

- Williamson, D.E.; Forbes, E.E.; Dahl, R.E.; Ryan, N.D. A genetic epidemiologic perspective on comorbidity of depression and anxiety. Child Adolesc. Psychiatr. Clin. N. Am. 2005, 14, 707–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, H.; McGinnity, A.; Meltzer, H.; Ford, T.; Goodman, R. Mental Health of Children and Young People in Great Britain, 2004, 1st ed.; Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Thapar, A.; Collishaw, S.; Pine, D.S.; Thapar, A.K. Depression in adolescence. Lancet 2012, 379, 1056–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dunn, V.; Goodyer, I.M. Longitudinal investigation into childhood- and adolescent-onset depression: Psychiatric outcome in early adulthood. Br. J. Psychiatry 2006, 188, 216–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Weissman, M.M.; Wolk, S.; Goldstein, R.B.; Moreau, D.; Adams, P.; Greenwald, S.; Klier, C.M.; Ryan, N.D.; Dahl, R.E.; Wickramaratne, P. Depressed adolescents grown up. JAMA 1999, 12, 1707–1713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mojtabai, R.; Olfson, M.; Han, B. National trends in the prevalence and treatment of depression in adolescents and young adults. Pediatrics 2016, 138, e20161878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bakken, A. Ungdata 2019. Nasjonale Resultater; NOVA: Oslo, Norway, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Bakken, A.; Osnes, S.M. Ungdomsskolen og videregående skole. In Ung i Oslo 2021; NOVA Rapport 9/21; NOVA: Oslo, Norway, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Cregeen, S.; Hughes, C.; Midgley, N.; Rhode, M.; Rustin, M. Psychoanalytic views of adolescent depression. In Short-Term Psychoanalytic Psychotherapy for Adolescents with Depression, 1st ed.; Catty, J., Ed.; Karnac Books: London, UK, 2017; pp. 11–36. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-IV; American Psychiatric Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-V; American Psychiatric Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Highlights of Changes from DSM-IV-TR to DSM-5; American Psychiatric Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby, J. Attachment, 1st ed.; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Bartholomew, K.; Horowitz, L.M. Attachment styles among young adults: A test of a four-category model. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1991, 61, 226–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armsden, G.C.; McCauley, E.; Greenberg, M.T. Parent and peer attachment in early adolescent depression. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 1990, 18, 683–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, G.W. Early loss and depression. In The Place of Attachment in Human Behavior, 1st ed.; Parkes, C.M., Stevenson-Hinde, J., Eds.; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1982; pp. 232–268. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, J.P.; McElhaney, K.B.; Land, D.J.; Kuperminc, G.P.; Moore, C.W.; O’Beirne–Kelly, H.; Kilmer, S.L. A Secure Base in Adolescence: Markers of Attachment Security in the Mother–Adolescent Relationship. Child Dev. 2003, 74, 292–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Daniel, B.; Wassell, S.; Gilligan, R. Child Development for Child Care and Protection Workers, 1st ed.; Jessica Kingsley Publishers: London, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Furman, W.; Buhrmester, D. Age and sex differences in perceptions of networks of personal relationships. Child Dev. 1992, 63, 103–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNelles, L.R.; Connolly, J.A. Intimacy between adolescent friends: Age and gender differences in intimate affect and intimate behaviors. J. Res. Adolesc. 1999, 9, 143–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinberg, L.; Morris, A.S. Adolescent development. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2001, 52, 83–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.Y.; McHale, S.M.; Osgood, D.W.; Crouter, A.C. Longitudinal course and family correlates of sibling relationships from childhood through adolescence. Child Dev. 2006, 77, 1746–1761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, G.; Tupling, H.; Brown, L. A parental bonding instrument. Br. J. Med. Psychol. 1979, 52, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, G. The measurement of pathogenic parental style and its relevance to psychiatric disorder. Soc. Psychiatr. 1984, 19, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, G. Parental characteristics in relation to depressive disorders. Br. J. Psychiatr. 1979, 134, 138–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohtaki, Y.; Ohi, Y.; Suzuki, S.; Usami, K.; Sasahara, S.; Matsuzaki, I. Parental bonding during childhood affects stress-coping ability and stress reaction. J. Health Psychol. 2017, 22, 1004–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enns, M.W.; Cox, B.J.; Larsen, D.K. Perceptions of parental bonding and symptom severity in adults with depression. Can. J. Psychiatry 2000, 45, 263–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Parker, G. Parental representations of patients with anxiety neurosis. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 1981, 63, 33–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kullberg, M.L.; Maciejewski, D.; Van Schie, C.C.; Penninx, B.W.J.H. Parental bonding: Psychometric properties and association with lifetime depression and anxiety disorders. Psychol. Assess. 2020, 32, 780–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, G. The parental bonding instrument. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatry Epidemiol. 1990, 25, 281–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favaretto, E.; Torresani, S.; Zimmermann, C. Further results on the Reliability of the Parental Bonding Instrument (PBI) in an Italian Sample of schizophrenic patients and their parents. J. Clin. Psychol. 2001, 57, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peh, O.H.; Rapisarda, A.; Sim, K.; Lee, J. Quality of parental bonding among individuals with ultra-high risk of psychosis and schizophrenia patients. Schizophr. Bull. 2018, 44, 123–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Parker, G.; Hadzi-Pavlovic, D.; Greenwald, S.; Weissman, M. Low parental care as a risk factor to lifetime depression in a community sample. J. Affect. Disord. 1995, 33, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raffagnato, A.; Angelico, C.; Fasolata, R.; Sale, E.; Gatta, M.; Miscioscia, M. Parental Bonding and Children’s Psychopathology: A Transgenerational View Point. Children 2021, 8, 1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmoeger, M.; Deckert, M.; Wagner, P. Maternal bonding behavior, adult intimate relationship, and quality of life. Neuropsychiatry 2018, 32, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wilhelm, K.; Gillis, I.; Parker, G. Parental Bonding and Adult Attachment Style: The Relationship between Four Category Models. Int. J. Womens Health Wellness 2016, 2, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.-L. Paternal/maternal attachment, peer support, social expectations of peer interaction, and depressive symptoms. Adolescence 2006, 41, 705–721. [Google Scholar]

- Boling, M.W.; Barry, C.M.; Kotchick, B.A.; Lowry, J. Relations among early adolescents’ parent-adolescent attachment, perceived social competence, and friendship quality. Psychol. Rep. 2011, 109, 819–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lieberman, M.; Doyle, A.B.; Markiewicz, D. Developmental patterns in security of attachment to mother and father in late childhood and early adolescence: Association with peer relations. Child Dev. 1999, 70, 202–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seginer, R. Adolescents’ Perceptions of Relationships with Older Sibling in the Context of Close Relationships. J. Res. Adolesc. 1998, 8, 287–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hersoug, A.G.; Ulberg, R. Siblings, friends, and parents: Who are the most important persons for adolescents? A pilot study of Adolescent Relationship Scale. Nord. Psychol. 2012, 64, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulberg, R.; Hersoug, A.G.; Høglend, P. Treatment of adolescents with depression: The effect of transference interventions in a randomized controlled study of dynamic psychotherapy. Trials 2002, 13, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ulberg, R.; Hummelen, B.; Hersoug, A.G.; Midgley, N.; Høglend, P.A.; Dahl, H.S.J. The first experimental study of transference work–in teenagers (FEST–IT): A multicentre, observer-and patient-blind, randomised controlled component study. BMC Psychiatry 2021, 21, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beck, A.T.; Steer, R.A.; Ball, R.; Ranieri, W. Comparison of Beck depression inventories –IA and –II in psychiatric outpatients. J. Pers. Assess. 1996, 67, 588–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Svanborg, P.; Asberg, M. A comparison between the Beck depression inventory (BDI) and the self-rating version of the Montgomery Åsberg depression rating scale (MADRS). J. Affect. Disord. 2001, 64, 203–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lecrubier, Y.; Sheehan, D.; Weiller, E.; Amorim, P.; Bonora, I.; Sheehan, K.; Janavs, J.; Dunbar, G. The MINI International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.) A Short Diagnostic Structured Interview: Reliability and Validity According to the CIDI. Eur. Psychiatry 1997, 12, 224–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfohl, B.; Blum, N.; Zimmerman, M. Structured Interview for DSM-IV Personality, 1st ed.; American Psychiatric Press: Washington DC, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Matsuoka, N.; Uji, M.; Hiramura, H.; Chen, Z.; Shikai, N.; Kishida, Y.; Kitamura, T. Adolescents’ attachment style and early experiences: A gender difference. Arch. Womens Ment. Health 2006, 9, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enns, M.W.; Cox, B.J.; Clara, I. Parental bonding and adult psychopathology: Results from the US national comorbidity survey. Psychol. Med. 2002, 32, 997–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overbeek, G.; ten Have, M.; Vollebergh, W.; de Graaf, R. Parental lack of care and overprotection. Soc. Psychiatry Epidemiol. 2007, 42, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomasgard, M.; Metz, W.P. Parental overprotection revisited. Child. Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 1993, 24, 67–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boer, F.; Goedhart, A.; Treffers, P. Siblings and their parents. In Children’s Relationships with Their Siblings: Developmental and Clinical Implications, 1st ed.; Boer, F., Dunn, J., Eds.; Lawrence Erlbaum: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1992; pp. 83–100. [Google Scholar]

- Whiteman, S.D.; McHale, S.M.; Soli, A. Theoretical perspectives on sibling relationships. J. Fam. Theory Rev. 2011, 3, 124–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Furman, W.; Buhrmester, D. Children’s perceptions of the personal relationships in their social networks. Dev. Psychol. 1985, 21, 1016–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voorpostel, M.; Blieszner, R. Intergenerational Solidarity and Support Between Adult Siblings. J. Marriage Fam. 2008, 70, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Volling, B.L.; Belsky, J. The Contribution of Mother-Child and Father-Child Relationships to the Quality of Sibling Interaction: A Longitudinal Study. Child Dev. 1992, 63, 1209–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heider, D.; Matschinger, H.; Bernert, S.; Alonso, J.; Angermeyer, M.C. Relationship between parental bonding and mood disorder in six European countries. Psychiatry Res. 2006, 143, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flouri, E.; Buchanan, A. The Role of Father Involvement and Mother Involvement in Adolescents’ Psychological Well-being. Br. J. Soc. Work 2003, 33, 399–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Goede, I.H.A.; Branje, S.J.T.; Delsing, M.J.M.H.; Meeus, W.H.J. Linkages Over Time Between Adolescents’ Relationships with Parents and Friends. J. Youth Adolesc. 2009, 38, 1304–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rubin, K.H.; Dwyer, K.M.; Kim, A.H.; Burgess, K.B. Attachment, Friendship, and Psychosocial Functioning in Early Adolescence. J. Early Adolesc. 2004, 24, 326–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derkman, M.M.; Engels, R.C.; Kuntsche, E.; van der Vorst, H.; Scholte, R.H. Bidirectional associations between sibling relationships and parental support during adolescence. J. Youth Adolesc. 2011, 40, 490–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Manassis, K.; Owens, M.; Adam, K.S.; West, M.; Sheldon-Keller, A.E. Assessing Attachment: Convergent Validity of the Adult Attachment Interview and the Parental Bonding Instrument. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 1999, 33, 559–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrindell, W.A.; Gerlsma, C.; Vandereycken, W.; Hageman, W.J.; Daeseleire, T. Convergent validity of the dimensions underlying the parental bonding instrument (PBI) and the EMBU. Pers. Individ. Differ. 1998, 24, 341–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qadir, F.; Stewart, R.; Khan, M.; Prince, M. The validity of the Parental Bonding Instrument as a measure of maternal bonding among young Pakistani women. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2005, 40, 276–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilhems, K.; Niven, H.; Parker, G.; Hadzi-Pavlovic, D. The stability of the Parental Bonding Instrument over a 20-year period. Psychol. Med. 2005, 35, 387–393. [Google Scholar]

- Tsaousis, I.; Mascha, K.; Giovazolias, T. Can Parental Bonding Be Assessed in Children? Factor Structure and Factorial Invariance of the Parental Bonding Instrument (PBI) Between Adults and Children. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2012, 43, 238–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Total (n = 68) Mean (SD) | |

|---|---|

| Age | 17.3 (0.7) |

| Beck Depression Inventory | 28.6 (9.1) |

| Montgomery and Åsberg Depression Scale | 22.2 (5.5) |

| N(%) | |

| Female | 57 (84) |

| Diagnoses | 68 (100) |

| Depressive disorder | 68 (100) |

| Social Phobia | 19 (28) |

| Panic Disorder | 13 (19) |

| General Anxiety | 17 (25) |

| Eating disorder | 2 (3) |

| PTSD | 2 (3) |

| Personality Disorders | 30 (44) |

| Depressive | 24 (35) |

| Avoidant | 19 (28) |

| Negativistic | 3 (4) |

| Obsessive compulsive | 3 (4) |

| Paranoid | 3 (4) |

| Dependent | 2 (3) |

| Borderline | 1 (1) |

| Histrionic | 1 (1) |

| Schizoid | 1 (1) |

| More than one Personality Disorder | 17 (25) |

| Care Mean (SD) | Control Mean (SD) | |

|---|---|---|

| Maternal | 26.2 (7) | 15.6 (7.5) |

| Paternal | 22.7 (7.9) | 12.8 (5.8) |

| Optimal Bonding N (%) | Absent Bonding N (%) | Affectionate Constraint N (%) | Affectionless Control N (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal | 28 (41) | 6 (9) | 14 (21) | 20 (29) |

| Paternal | 21 (31) | 14 (21) | 13 (19) | 20 (29) |

| N | Mean (SD) | |

|---|---|---|

| What is your quality of life like now? | 68 | 4.5 (1.6) |

| The importance of friends | ||

| How much do your friends mean to you? | 68 | 8.5 (1.5) |

| How much do you mean to your friends? | 68 | 6.8 (2.1) |

| The importance of siblings | ||

| How much do your siblings mean to you? | 61 | 8.7 (1.8) |

| How much do you mean to your siblings? | 61 | 8.0 (2.1) |

| The importance of mother | ||

| How much does your mother mean to you? | 64 | 8.7 (1.8) |

| How much do you mean to your mother? | 64 | 9.1 (6) |

| The importance of father | ||

| How much does your father mean to you? | 64 | 8.4 (2.1) |

| How much do you mean to your father? | 64 | 8.4 (2.2) |

| Maternal Care | Maternal Control | Paternal Care | Paternal Control | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| What is your quality of life like now? | 0.308 * | −0.266 * | −0.041 | 0.035 |

| How much do your friends mean to you? | 0.145 | −0.352 ** | 0.089 | 0.080 |

| How much do you mean to your friends? | 0.196 | −0.269 * | −0.034 | 0.073 |

| How much do your siblings mean to you? | −0.067 | −0.139 | 0.278 * | −0.183 |

| How much do you mean to your siblings? | 0.175 | −0.157 | 0.314 * | −0.127 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fahs, S.C.; Ulberg, R.; Dahl, H.-S.J.; Høglend, P.A. Parental Bonding and Relationships with Friends and Siblings in Adolescents with Depression. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 6530. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19116530

Fahs SC, Ulberg R, Dahl H-SJ, Høglend PA. Parental Bonding and Relationships with Friends and Siblings in Adolescents with Depression. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(11):6530. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19116530

Chicago/Turabian StyleFahs, Sarah Christine, Randi Ulberg, Hanne-Sofie Johnsen Dahl, and Per Andreas Høglend. 2022. "Parental Bonding and Relationships with Friends and Siblings in Adolescents with Depression" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 11: 6530. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19116530

APA StyleFahs, S. C., Ulberg, R., Dahl, H.-S. J., & Høglend, P. A. (2022). Parental Bonding and Relationships with Friends and Siblings in Adolescents with Depression. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(11), 6530. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19116530