Gendered Citizenship, Inequality, and Well-Being: The Experience of Cross-National Families in Qatar during the Gulf Cooperation Council Crisis (2017–2021)

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Cross-National Marriage and Citizenship Law in the State of Qatar

1.2. State Law and Gender-Based Citizenship in Qatar: Heritage and Progress

1.3. Citizenship and Well-Being

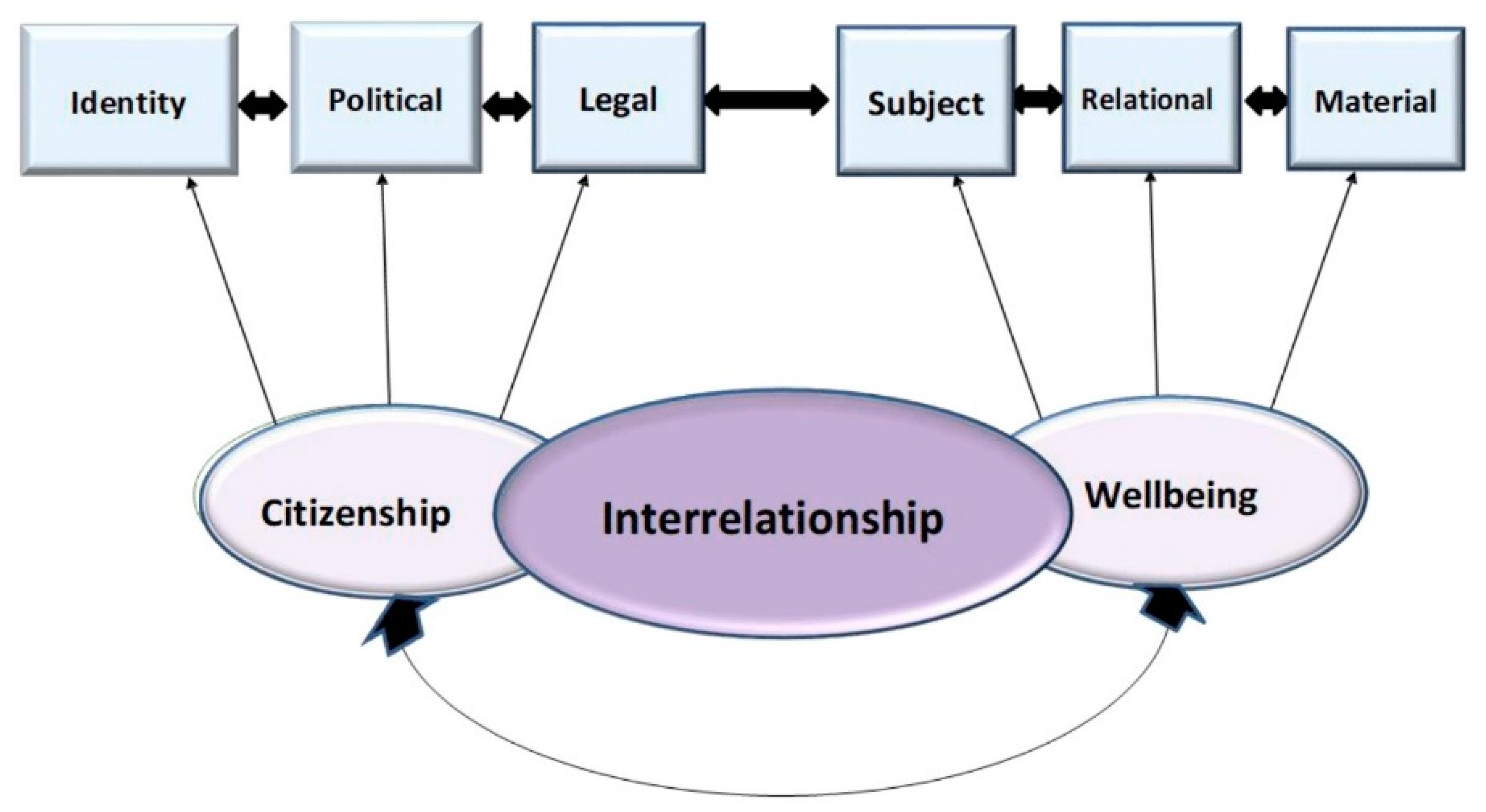

1.4. Perceived Interrelationship between Citizenship and Well-Being: A New Multidimensional Paradigm

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Analysis

2.2. Ethics and Quality Assurance

2.3. Participants

2.4. Procedure

3. Results

3.1. Subjective Dimension

- Psychological effects

The blockade is a black mark in the entire history of the Gulf region, not only for Qatar; the effects will stay for years to come. It is difficult to recover from what happened, mainly when everyone uses the media to express hatred and hostility (QMP-14).

I am anxious because I cannot reconcile with all those sitting around me. I have psychological stresses, and I am not my usual self. Even though I try not to be tragic, I can see my life is becoming darker and more tragic (QFP-2).

As a result of the psychological and financial pressure, I could not get out or socialize with others and my friends. The way I looked before was different than how I look now. My beard looked awful (QMP-10).

- Family Separation, Fear, and Anxiety

Psychologically, I feel very fearful and anxious about the future of my children and husband. There is a chance they will be deported; even the idea of speaking about it frightens me. It makes me feel fearful, the same way when I am thinking about the future (QFP-3).

I am always concerned and anxious about being separated from my children. If any problem occurs between my husband and me, it may end our marriage, and my husband will take the children and go back to Saudi Arabia. My children will be the victims (QFP-8).

I worry about my children growing up in their mother’s environment and changing their ideas and beliefs. They are still at an early stage where they are easily influenced. I am afraid of not being able to see them; I am worried they will completely change the way they think of me and Qatar (QMP-14).

- Effects on Marital Relationships

Due to the blockade, I lost all my investments in Saudi Arabia. My depression impacted my relationship with my wife and children; it got worse and deteriorated day after day. There were too many fights and tensions between us. In the end, she left the house and went back to her parent’s house, where she stayed for over two months. The marriage almost ended in divorce.

I am a father, born as a Qatari citizen and held the nationality of this state, but this is not the case with “the other person” [his former non-Qatari wife]. I do not mean to belittle the “other person”. I am saying this out of patriotism and loyalty; it is the sense of loyalty and belonging (QMP-12).

I know people who are now married or engaged to spouses from Saudi Arabia. After the blockade, everything was ruined. People who marry within their country [nationality] are more likely to feel psychologically stable (QMP-14).

- Regret and Opposition to Cross-National Marriages

Wishing our situations are like my [other] sister, who is married to a Qatari man (QFP-5). My sister and I have the same problem [married to Saudis]. When we discuss our similar situation, we agree that “it was a wrong decision that we married to Saudi men”.

About a week ago, my husband asked me: “Do you regret that you are married to me”? I told him: “No” … inside me, I feel I do not regret it, but I hoped for a better situation (QFP-6).

I am married to a non-Qatari. Although I do not underestimate anyone or nationality, do not marry anyone outside Qatar because we do not know what the future holds (QMP-14).

Considering the time before the blockade, when I was still married to someone from another country, I had to travel two to three times a month between Qatar and Saudi Arabia. Speaking of the blockade now, I do not know what may happen in the future; if I marry a woman from a country other than Qatar, especially during a political problem. This is why I do not encourage such [cross-national] marriages (QMP-14).

- Effects on Children

My daughter was afraid that blockading countries would start a war, invade and kill us. Her words reminded me of when I was young [during a similar situation]. I used to hear the teachers in school saying: “They will attack us, and they will destroy us” (QMP-15).

In the past, the children used to visit their aunts. I am afraid to say they hate them. My little child says, “We do not want to go to Bahrain anymore because they are blocking us” (N-QFP-20).

- Effects on Extended Family Relations

My mother is an Emirati. My aunts and uncles live in Bahrain and Saudi Arabia. Now, we live in isolation [even though] we used to have a great relationship. My brothers are married to my cousins [from Saudi Arabia], and my sisters are married to my Aunt’s sons [from Bahrain]. Because of the new blockading state rules, especially the “UAE Criminalization of Sympathy Law”, they are afraid to speak with us (QMP-15).

I have the same feeling of sadness and anger. I feel sadder over time when I remember that my father passed away, and I was not able to see him (QFP-21).

My wife’s only concern is that she wants to see her brothers and sisters and find a way to do it, since she is an Emirati by origin. The problem is that she is Qatari now, so it is hard for her to see them! She must obtain a permit from the UAE to enter the country (QMP-15).

It has become difficult for them [my extended family members] to call us because they are afraid; we are also scared to call them because they may suffer. Some people were hurt when they called their families; we heard that they were arrested and deported (QMP-15).

We [non-Qatari women] are the most vulnerable because we got separated from our extended families, and we cannot travel to see them (N-QFP-18).

- Effects on Social Relations: Isolation

My dealing with people has become more difficult since I began to avoid places where I would talk about the [blockade] crisis. There were WhatsApp groups I was part of, but I left every single one. I mean it. We do not talk about it. We do not have any discussion about the blockade. Even if someone mentions it, we act as if we did not hear it. Leaving the group was the best solution (N-QFP-18).

I have lost trust in people; it has faded away. I found it hard to maintain social contacts. Being with people was becoming less important. I began focusing more on my family, and I want to devote more of my life to them (QFP-3).

This [blockade] has affected me and my work. My job is very demanding, and I must be awake and focused 200%. I tried not to engage with anyone and did not want to travel anywhere. Whenever I travel to a country, I stay in my hotel room. I felt my mind was preoccupied thinking about them, especially since there was no contact between us (QMP-14).

I never missed any activities in Qatar. I used to write, attend seminars, and post on my webpage. For example, I do not miss the Arab and International Relations forum. But now I have my laptop with me all the time. I stopped all activities (N-QMP-23).

3.2. Legal Dimension: Family Laws and Policies

- Women’s Views about Citizenship: Gender Inequality

As a Qatari woman married to a non-Qatari man, I could not get housing. They [the officials] say a woman in Qatar should follow her husband. They tell me to take my kids and go back to my husband’s country. They cannot decide for me or deprive me of my right to choose. I am a human being. At last, it is up to me to decide, not them (QFP-3).

The law talks about equality between men and women, but this equality means nothing; there is no real equality.

The law allows the naturalization of the wife of a Qatari man; why don’t you do the same for the husband of a Qatari woman? The government keeps talking about families and celebrating the ‘Family Day’ and ‘Family Welfare’. So why does the law differentiate between a Qatari man married to a Saudi woman and a Qatari woman married to a Saudi man? So we are not equal (QFP-8).

We tried to solve Qatari women’s concerns about citizenship. However, officials told us that this [granting citizenship to their children and spouses] can cause “genealogical mixing”. So Qatari men can marry Egyptian, Indian, Bengali, Moroccan, or Syrian women. Also, these women can bring their parents here and decide who they [their children] should marry. “Why is it only considered a genealogical mix if the woman is Qatari”? (QFP-4).

When the issue of permanent residency came up, I felt as if the Council was telling us: “You either get it or forget [the passport]”. Permanent residence law is similar to a valid visa. Granting children permanent residency would mean muting us. My children are still young; they do not work or attend university. We long for a decision to naturalize Qatari women’s children (QFP-5).

- Men and Gendered Citizenship: Women are More Privileged than Men

I swear I would not stay under my husband’s authority if I were a woman. I would rather be divorced because he [my husband] will pay me monthly. I would be an idiot if I agreed to remain as his wife. Women enjoy maternity hours. They have off days more than men and have more rights than the law grants men (QMP-17).

Society is striving to give women their rights. When a woman leaves her house, the judge makes her husband pay her dowry, including the postponed dowry and alimony. She [a Qatari woman] can force her husband to leave the house, but he cannot evict her. So why should she be equal to me? (QMP-12).

These laws promote differences in perceptions of equality and create conflicts within families while giving women more power over men. Even if such a [non-Qatari] person has spent all their lives in Qatar, they still have no relatives. I may offer this person 40% of citizenship privileges, but not all citizenship rights. Therefore, I can never deal with this person as an equal citizen (QMP-17).

Even after divorce, she [his Qatari wife] receives her basic needs such as food. “When fathers tell their daughters to get divorced and return to their country, you will probably understand why divorces are so common today” (N-QMP-23).

I believe the Qatari woman has her rights in society, but the society oppresses her with traditional and family values (QMP-12).

Although I divorced my wife, the law required me to provide travel permission to my ex-wife and daughter when they travel to Egypt (QMP-13).

- Effects on Children’s Well-being: The Invisible Citizens

What should I do? My husband is out of work; my son is living in the State of Qatar with no I.D. proof. My son is not in the system, he does not virtually exist in terms of his vaccinations and sickness, and he is about to be two years old. My daughter’s passport has expired, and my other daughter’s passport expires next year in September (2020). What shall I do? (QFP-1).

I am a resident of Doha. My wife is Qatari. The government issued a ruling about not giving my girl a passport due to the political crisis between Qatar and the UAE. It was a clear legal text. The [GCC] crisis is not my fault; when there is a political problem between the two countries, what do the cross-national and Emirati families do with that?

According to Emirati Law, the parents can demand citizenship for their child [if born outside the country] if they are under three years old; otherwise, they will be denied citizenship. Thus, I cannot demand an I.D. for my daughter (N-QMP-23).

When I took [my daughter] to the hospital, she was considered a foreigner, and I should pay (her medical costs). She has no health insurance I.D. Thus, I had to take her to a private hospital. As a baby, she received a vaccination book. She does not have any other proof (QFP-2).

My son cannot receive education; I went to private kindergartens, but they sought his birth certificate. The one I had is unofficial. They demanded a passport or I.D. card to prove [that] the child does exist; what can I do? (QFP-2).

Before the blockade, I did not ask for citizenship for the children. My only concern now is passing citizenship on to my children so that they will feel settled and comfortable (QFP-4).

My daughter has the Qatari document [residency]. However, she will have second priority when applying for a job because her mother is a Qatari married to a non-Qatari (QFP-4).

3.3. Resources and Material Dimension

- Limited access to land and loans

I believe that this law is biased. As far as land goes, I do not see equality. Sometimes, when I seek my rights, they tell me that I am naturalized. Due to this law, my father and I could not get citizenship (QMP-13).

- The Experience of Non-Qatari women married to Qatari men

I have the right to access health care at hospitals. I have been treated the same as a Qatari. I joined Qatar University without fees, the same as a Qatari citizen. After graduation, I had a work interview with a Qatari woman. I was employed. Frankly, there was no discrimination (N-QFP-18).

When he brought me the [citizenship] papers to sign, I cried that day as if I [had] lost both of my parents. It is tough to abandon your citizenship. When I went to Bahrain with the Qatari passport, my uncle asked me: “Did you dump your country”? I won’t forget his words! I replied, “No, I did not, but it was for the sake of my children; I do not want them to be unemployed. If I had kept my Bahraini nationality, I would not have enrolled in the university and got a Qatari citizen’s privileges. I would not have been employed because priority is always given to Qataris. I have a son in the military corps. If his mother were not a Qatari citizen, he would not have joined this corps. It has been a blessing. I am now reaping the fruits of the decision I took 26 years ago” (N-QFP-21).

3.4. Identity Dimension

- Identity Crisis

Why don’t I become a Qatari? When I heard my son asking this question, I was shocked and asked him: “Why do you want to become a Qatari? What is wrong with being a Bahraini”? He replied: “Because they [the Bahrainis] are among the blockading countries, and I do not want to belong to one of these countries because, at school, kids say that we belong to the blockading countries. When will this situation end”? He still does not know how to pronounce BLOCKADE (حصار) correctly or differentiate between it and other similar words in Arabic, i.e., STORM إعصار))? (QFP-4).

Lately, I felt he [my son] had no pride in his Egyptian identity. He used to like that before the blockade, but he did not like it anymore. I think he loves to speak more Qatari dialect, even how he says. Now, he wants to mingle with the Qatari people. I think he was trying to forget about being Egyptian and avoiding talking to someone with the Egyptian dialect (QFP-3).

My nine-year-old son told me: “In school, they say: ‘You are from the countries of the blockade”. Why do they tell us that we are from the countries of the blockade”? As a precaution, I told him to tell his classmates that he is from Qatar, lives in Qatar, and does not know anything about these countries. The next day, I asked him: “Did you tell them that you are a Qatari and live in Qatar”? He answered, “Yes. They even said, ‘Why didn’t you tell us before that you are a Qatari living in Qatar? We thought you were from the blockading countries”! He felt good that he could deceive them (QFP-4).

I noticed that my daughter’s sense of belonging to Qatar strengthened after the blockade. Suddenly, she talked about politics and told us what we should do and what Shaikha Mouza (Her Highness) and Shaikh Tamim did or said. In a sense, it is like how we all talk about safeguarding Qatar (QMP-15).

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions and Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Monthly Statistics for Web Final: Ministry of Developed Planning and Statistics. Population. Available online: https://www.psa.gov.qa/en/statistics1/pages/topicslisting.aspx?parent=population&child=population (accessed on 9 August 2021).

- Country Reports on Human Rights Practices: Qatar. Available online: https://www.state.gov/reports/2018-country-reports-on-human-rights-practices/qatar (accessed on 29 May 2021).

- Ahmad, B.; Fouad, F.M.; Zaman, S.; Phillimore, P. Women’s health and well-being in low-income formal and informal neighbourhoods on the eve of the armed conflict in Aleppo. Int. J. Public Health 2018, 64, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Schmid, K.; Muldoon, O.T. Perceived Threat, Social Identification, and Psychological Well-Being: The Effects of Political Conflict Exposure. Political Psychol. 2013, 36, 75–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- State-Society Relations and Citizenship in Situations of Conflict and Fragility: Topic Guide Supplement. Available online: https://gsdrc.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/CON88.pdf (accessed on 7 August 2021).

- Cummings, E.M.; Merrilees, C.E.; Taylor, L.K.; Mondi, C.F. Developmental and social–ecological perspectives on children, political violence, and armed conflict. Dev. Psychopathol. 2016, 29, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Khamis, V. Political Violence and the Palestinian Family: Implications for Mental Health and Well-Being, 1st ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Doha International Family Institute. The Impact of the Blockade on Families in Qatar; Hamad Bin Khalifa University Press: Doha, Qatar, 2018; Available online: https://www.difi.org.qa/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/Blockade-English-FINAL.pdf (accessed on 10 August 2021).

- Bloemraad, I.; Sheares, A. Understanding Membership in a World of Global Migration: (How) Does Citizenship Matter? Int. Migr. Rev. 2017, 51, 823–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gee, G.C.; Ford, C.L. Structural Racism and Health Inequities. Du Bois Rev. Soc. Sci. Res. Race 2011, 8, 115–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gee, G.C.; Morey, B.N.; Walsemann, K.M.; Ro, A.; Takeuchi, D.T. Citizenship as privilege and social identity: Implications for psychological distress. Am. Behav. Sci. 2016, 60, 680–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riley, A.; Varner, A.; Ventevogel, P.; Taimur Hasan, M.M.; Welton-Mitchell, C. Daily stressors, trauma exposure, and mental health among stateless Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh. Transcult 2017, 54, 304–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharahsheh, S.T.; Mohieddin, M.M.; Almeer, F.K. Marrying Out: Trends and Patterns of Mixed Marriage amongst Qataris. Int. J. Soc. Sci. Stud. 2015, 3, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Alharahsheh, S.T.; Almeer, F.K. Cross-National Marriage in Qatar. Hawwa 2018, 16, 170–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telve, K. Family Life across the Gulf: Cross-Border Commuter’ Transnational Families between Estonia and Finland. Doctor of Philosophy in Ethnology; University of Tartu Press: Tartu, Estonia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kaaristo, M. Doctoral Dissertation on cross-national family life across the Gulf of Finland. Folk. Electron. J. Folk. 2019, 77, 209–211. [Google Scholar]

- Bryceson, D.F. Transnational families negotiating migration and care life cycles across nation-state borders. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2019, 45, 3042–3064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Riley, N.E.; Brunson, J. International Handbook on Gender and Demographic Processes; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Longo, G.M. Keeping it in “the family”: How gender norms shape US marriage migration politics. Gend. Soc. 2018, 32, 469–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodge, R.; Daly, A.P.; Huyton, J.; Sanders, L.D. The challenge of defining wellbeing. Int. J. Wellbeing 2012, 2, 222–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Caeiro, A. The Politics of Family Cohesion in the Gulf: Islamic Authority, new Media, and the Logic of the Modern Rentier State. Arab. Archaeol. Epigr. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monthly Statistics for Web Final: Ministry of Developed Planning and Statistics. Available online: https://www.psa.gov.qa/en/statistics1/pages/topicslisting.aspx?parent=General&child=QMS (accessed on 10 August 2021).

- Monthly Statistics for Web Final: Ministry of Developed Planning and Statistics. Marriage and Divorce. Available online: https://www.psa.gov.qa/en/statistics1/pages/topicslisting.aspx?parent=Population&child=MarriagesDivorces (accessed on 15 August 2021).

- Nitsevich, V.F.; Moiseev, V.V.; Sudorgin, O.A.; Stroev, V.V. Why Russia Cannot Become the Country of Prosperity. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2019, 272, 032148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babar, Z. Population, Power, and Distributional Politics in Qatar. J. Arab. Stud. 2015, 5, 138–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, C.M. Dubai: The Vulnerability of Success; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Joseph, S. Intimate Selving in Arab Families: Gender, Self, and Identity; Syracuse University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Sater, J. Migration and the Marginality of Citizenship in the Arab Gulf Region: Human Security and High Modernist Tendencies; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 224–245. [Google Scholar]

- Mackert, J.; Turner, B.S. The Transformation of Citizenship, Volume 2: Boundaries of Inclusion and Exclusion; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Joseph, S. Gender and Citizenship in the Arab World. Al-Raida J. 1970, 129, 8–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amri, L.; Ramtohul, R. Gender and Citizenship in the Global Age; African Books Collective-CODESRIA : Dakar, Senegal, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Chari, W.A. Gendered citizenship and women’s movement. EPW 2009, 44, 47–57. [Google Scholar]

- El-Saadani, S.M. Divorce in the Arab Region: Current Levels, Trends and Features. In Proceeding of the European Population Conference, Liverpool, UK, 23 June 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Oldfield, S.; Mathsaka, N.S.; Salo, E.; Schlyter, A. In bodies and homes: Gendering citizenship in Southern African cities. Urbani Izziv 2019, 30, 37–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tok, M.E.; Alkhater, L.R.; Pal, L.A. Policy-Making in a Transformative State: The Case of Qatar. In Policy-Making in a Transformative State; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, J.S.; Paschyn, C.; Mir, S.; Pike, K.; Kane, T. Inmajaalis al-hareem: The complex professional and personal choices of Qatari women. DIFI Fam. Res. Proc. 2015, 2015, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shura Council Reviews Recommendations to Grant P.R. to Children of Qatari Women Married to Non-Qataris. Qatar Tribune. Available online: https://www.qatar-tribune.com/news-details/id/204380 (accessed on 17 August 2021).

- Lewicka, M. Ways to make people active: The role of place attachment, cultural capital, and neighborhood ties. J. Environ. Psychol. 2005, 25, 381–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constitution of the World Health Organization. Basic Documents, 51st ed.; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Diener, E.D.; Suh, M.E. Subjective well-being and age: An international analysis. Annu. Rev. Gerontol. Geriatr 1997, 17, 304–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E.; Lucas, R.E.; Oishi, S. Advances and Open Questions in the Science of Subjective Well-Being. Collabra Psychol. 2018, 4, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Seligman, M. PERMA and the building blocks of well-being. J. Posit. Psychol. 2017, 13, 333–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Western, M.; Tomaszewski, W. Subjective well-being, objective well-being and inequality in Australia. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0163345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McNaught, A. Defining Wellbeing. In Understanding Wellbeing: An Introduction for Students and Practitioners of Health and Social Care; Knight, A., McNaught, A., Eds.; Banbury: Lantern, Singapore, 2011; pp. 7–23. [Google Scholar]

- Hicks, S.; Tinkler, L.; Allin, P. Measuring Subjective Well-Being and its Potential Role in Policy: Perspectives from the UK Office for National Statistics. Soc. Indic. Res. 2013, 114, 73–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Report by the Commission on the Measurement of Economic Performance and Social Progress. Available online: http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.215.58&rep=rep1&type=pdf (accessed on 12 August 2021).

- La Placa, V.; McNaught, A.; Knight, A. Discourse on wellbeing in research and practice. Int. J. Wellbeing 2013, 3, 116–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Boarini, R.; Johansson, Å.; Mira d’Ercole, M. Alternative Measures of Well-Being. OECD 2006, 1–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasser, N.; Fakhroo, H. An Investigation of the Self-Perceived Well-Being Determinants: Empirical Evidence from Qatar. SAGE 2021, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leydet, D. Citizenship; Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy: Standford, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- White, S.C. But What is Well-Being? A Framework for Analysis in Social and Development Policy and Practice. In Conference on Regeneration and Well-Being: Research into Practice University of Bradford, 24-25 April 2008; University of Bradford: Bradford, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Clayton, A.; O’Connell, M.J.; Bellamy, C.; Benedict, P.; Rowe, M. The Citizenship Project Part II: Impact of a Citizenship Intervention on Clinical and Community Outcomes for Persons with Mental Illness and Criminal Justice Involvement. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2012, 51, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georghiades, A.; Eiroa-Orosa, F.J. A Randomised Enquiry on the Interaction Between Wellbeing and Citizenship. J. Happiness Stud. 2019, 21, 2115–2139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iezzi, D.F.; Deriu, F. Women active citizenship and wellbeing: The Italian case. Qual. Quant. 2013, 48, 845–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zalewska, A.M.; Zawadzka, A. Subjective well-being and Citizenship dimensions according to individualism and collectivism beliefs among Polish adolescents. Curr. Issues Pers. Psychol. 2016, 3, 155–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lambert, L.; Raven, N.; Zaidi, N.P. Happiness in the United Arab Emirates: Conceptualisations of happiness among Emirati and other Arab students. Int. J. Happiness Dev. 2015, 2, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harper, F.D.; Guilbault, M.; Tucker, T.; Austin, T. Happiness as a Goal of Counseling: Cross-cultural Implications. Int. J. Adv. Couns. 2007, 29, 123–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brabeck, K.M.; Lykes, M.B.; Hershberg, R. Framing immigration to and deportation from the United States: Guatemalan and Salvadoran families make meaning of their experiences. Community Work Fam. 2011, 14, 275–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, A.D.; Ruelas, L.; Granger, D.A. Household fear of deportation in Mexican-origin families: Relation to body mass index percentiles and salivary uric acid. Am. J. Hum. Biol. 2017, 29, e23044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meijer, R.; Butenschøn, N. The Crisis of Citizenship in the Arab World; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2017.

- Torres, J.M.; Deardorff, J.; Gunier, R.B.; Harley, K.G.; Alkon, A.; Kogut, K.; Eskenazi, B. Worry about Deportation and Cardiovascular Disease Risk Factors among Adult Women: The Center for the Health Assessment of Mothers and Children of Salinas Study. Ann. Behav. Med. 2018, 52, 186–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Valenzuela, R. Navigating Parental Fitness: Noncitizen Latino Parents and Transnational Family Reunification (Doctoral Dissertation, Doctor of Philosophy); Indiana University: Bloomington, IN, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Menjívar, C.; Abrego, L.J.; Schmalzbauer, L.C. Immigrant Families; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Murthy, R.S.; Lakshminarayana, R. Mental health consequences of war: A brief review of research findings. World Psychiatry 2006, 5, 25–30. [Google Scholar]

- Victor, A.M.; Bernat, D.H.; Bernstein, G.A.; Layne, A.E. Effects of parent and family characteristics on treatment outcome of anxious children. J. Anxiety Disord. 2007, 21, 835–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lorenzo-Blanco, E.I.; Unger, J.B. Ethnic Discrimination, Acculturative Stress, and Family Conflict as Predictors of Depressive Symptoms and Cigarette Smoking among Latina/o Youth: The Mediating Role of Perceived Stress. J. Youth Adolesc. 2015, 44, 1984–1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Council of La Raza & Unidosus. Available online: https://www.loc.gov/item/lcwaN0004389/ (accessed on 15 August 2021).

- Artiga, S.; Lyons, B. Family Consequences of Detention/Deportation: Effects on Finances, Health, and Well-Being; Kaiser Family Foundation: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Gulbas, L.E.; Zayas, L.H.; Yoon, H.; Szlyk, H.; Aguilar-Gaxiola, S.; Rey, G.N. Deportation experiences and depression among U.S. citizen-children with undocumented Mexican parents. Child: Care, Health Dev. 2015, 42, 220–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zayas, L.H.; Heffron, L.C. Disrupting Young Lives: How Detention and Deportation Affect US-Born Children of Immigrants; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2016; Available online: https://www.apa.org/pi/families/resources/newsletter/2016/11/detention-deportation (accessed on 1 March 2022).

- Rivera, F.I.; Guarnaccia, P.J.; Mulvaney-Day, N.; Lin, J.Y.; Torres, M.; Alegria, M. Family cohesion and its relationship to psychological distress among Latino groups. Hisp. J. Behav. Sci. 2008, 30, 357–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ryabov, I.; Zhang, Y. Entry and stability of cross-national marriages in the United States. J. Fam. Issues 2019, 40, 2687–2706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Anitha, S.; Roy, A.; Yalamarty, H. Gender, migration, and exclusionary citizenship regimes: Conceptualizing cross-national abandonment of wives as a form of violence against women. Violence Against Women 2018, 24, 747–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qureshi, K.; Charsley, K.A.H.; Shaw, A. Marital instability among British Pakistanis: Transnationality, conjugalities and Islam. Ethn. Racial Stud. 2012, 37, 261–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lavee, E.; Dallal, E.; Strier, R. Families in Poverty and Noncitizenship: An Intersectional Perspective on Economic Exclusion. J. Fam. Issues 2021, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, J.; Moselle, S. Forced Migrant Youth’s Identity Development and Agency in Resettlement Decision-Making: Liminal Life on the Myanmar-Thailand Border. Migr. Mobility, Displac. 2016, 2, 110–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabrielli, G.; Impicciatore, R. Breaking down the barriers: Educational paths, labour market outcomes and wellbeing of children of immigrants. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2021, 48, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prilleltensky, I. Meaning-making, mattering, and thriving in community psychology: From co-optation to amelioration and transformation. Psychosoc. Interv. 2014, 23, 151–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Erdal, M.B. Theorizing interactions of migrant transnationalism and integration through a multiscalar approach. Comp. Migr. Stud. 2020, 8, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horst, C.; Erdal, M.B.; Jdid, N. The “good citizen”: Asserting and contesting norms of participation and belonging in Oslo. Ethn. Racial Stud. 2019, 43, 76–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spinozzi, P.; Mazzanti, M. Cultures of Sustainability and Wellbeing; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Osler, A.; Starkey, H. Extending the theory and practice of education for cosmopolitan citizenship. Educ. Rev. 2018, 70, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Abu-Ras, W.; Elzamzamy, K.; Burghul, M.M.; Al-Merri, N.H.; Alajrad, M.; Kharbanda, V.A. Gendered Citizenship, Inequality, and Well-Being: The Experience of Cross-National Families in Qatar during the Gulf Cooperation Council Crisis (2017–2021). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 6638. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19116638

Abu-Ras W, Elzamzamy K, Burghul MM, Al-Merri NH, Alajrad M, Kharbanda VA. Gendered Citizenship, Inequality, and Well-Being: The Experience of Cross-National Families in Qatar during the Gulf Cooperation Council Crisis (2017–2021). International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(11):6638. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19116638

Chicago/Turabian StyleAbu-Ras, Wahiba, Khalid Elzamzamy, Maryam M. Burghul, Noora H. Al-Merri, Moumena Alajrad, and Vardha A. Kharbanda. 2022. "Gendered Citizenship, Inequality, and Well-Being: The Experience of Cross-National Families in Qatar during the Gulf Cooperation Council Crisis (2017–2021)" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 11: 6638. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19116638

APA StyleAbu-Ras, W., Elzamzamy, K., Burghul, M. M., Al-Merri, N. H., Alajrad, M., & Kharbanda, V. A. (2022). Gendered Citizenship, Inequality, and Well-Being: The Experience of Cross-National Families in Qatar during the Gulf Cooperation Council Crisis (2017–2021). International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(11), 6638. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19116638