Psychological and Social Impact of HIV on Women Living with HIV and Their Families in Low- and Middle-Income Asian Countries: A Systematic Search and Critical Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. The Systematic Search of Literature

2.2. Inclusion Criteria

TITLE-ABS-KEY ((hiv* OR “Human immunodeficiency virus” OR aids)) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY ((wives OR wife OR mothers OR female* OR girl* OR women OR woman)) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY ((predictor* OR “risk factor*” OR determinant* OR “sexual behaviour” OR “multiple sex partner*” OR extramarital* OR “sell* sex*” OR “transactional sex” OR prostitut* OR “sex work” OR condom* OR ”unsafe sex” OR “unprotected sex” OR knowledge OR “social influenc*” OR “peer influenc*” OR “social norm* “OR cultur* OR sociocultural* OR socioeconomic* OR “social environmental* “OR socioenvironment* OR stigma OR discriminat* OR “psychological impact” OR “social impact” OR stress OR distress OR depression OR “psychosocial impact”)) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY ((family* OR families)) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY (((developing OR “Less developed” OR “low resource*” OR disadvantaged OR “resource limited” OR poor OR “low* OR middle income*”) W/0 (countr* OR region* OR nation? OR area*))) AND (LIMIT-TO (PUBYEAR, 2021) OR LIMIT-TO (PUBYEAR, 2004)) AND (LIMIT-TO (LANGUAGE, “English”))

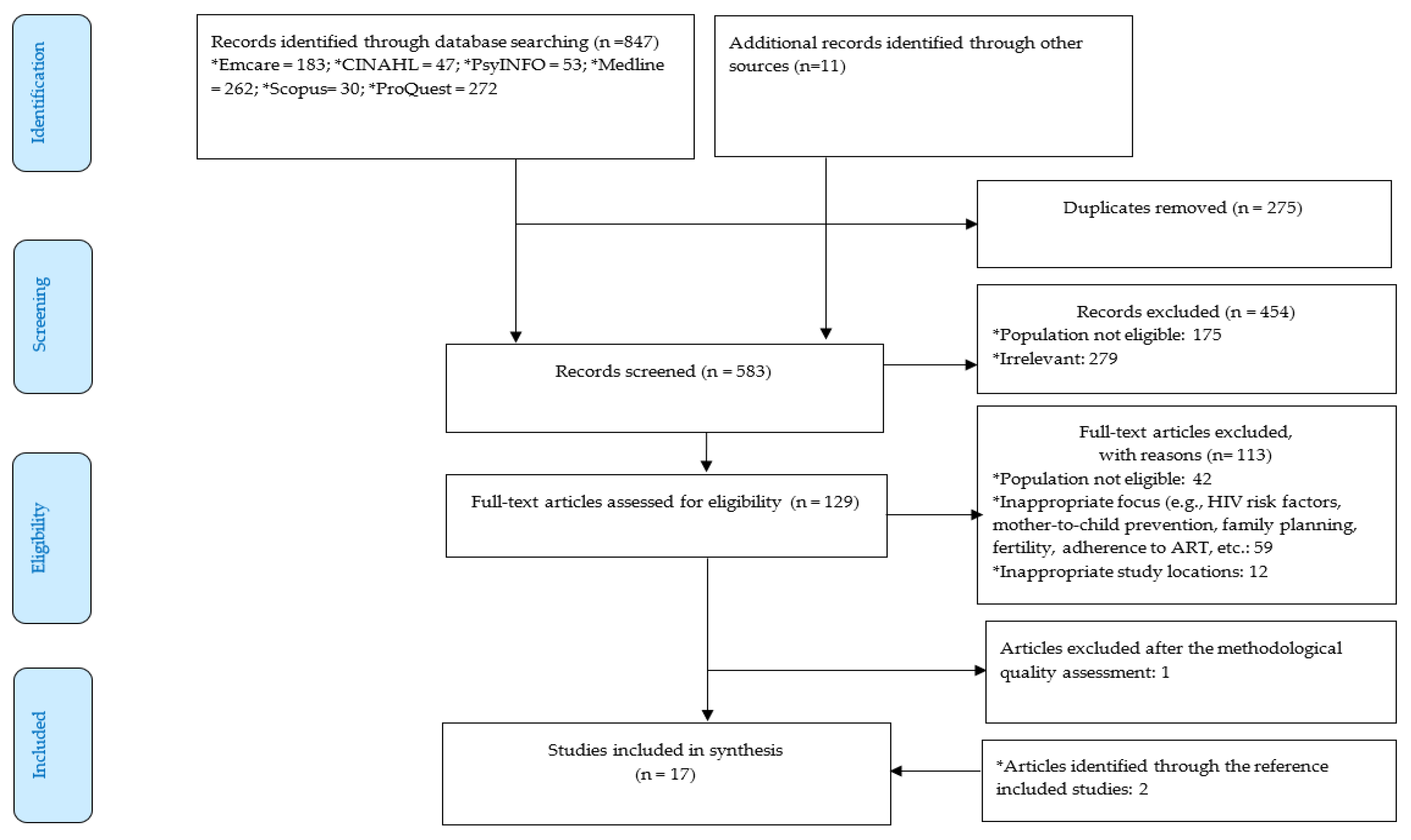

2.3. Selection of the Studies and Methodological Quality Assessment

2.4. Data Extraction and Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Description of the Included Studies

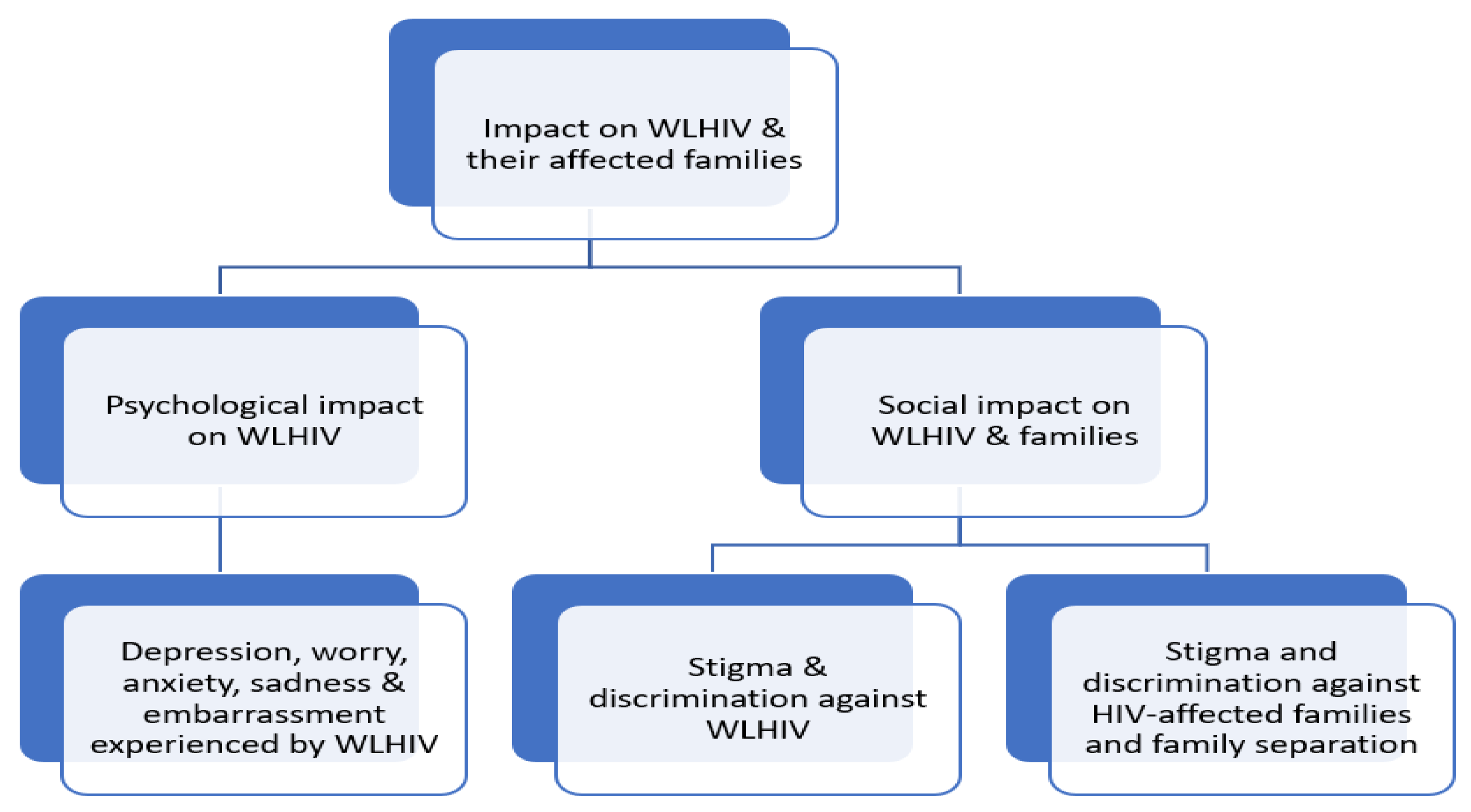

3.2. Impact of HIV on WLHIV and Their Families

| CATEGORY | SELECTED QUOTES |

|---|---|

| PSYCHOLOGICAL IMPACT OF HIV ON WLHIV AND THEIR FAMILIES | |

Psychological impact on WLHIV

| “I fear my child will be infected with HIV. We are HIV positive and of course there is a high probability for the child of getting infected” Female participant, Vietnam [39]. |

| “I feel why should I live in this world, or for what am I living? Sometimes I am completely down, depressed emotionally. Sometimes I have feeling of even killing myself or committing suicide.” Female participant, India [34]. “My husband and I fear that we will die early on, when the child is two or three years old only. …. The child who is an orphan will suffer great misery. It will die soon. How will my child live? I cannot imagine what it will be like, I only know that we will be in great misery too.” Female participant, Vietnam [39]. “Every night I cry. I still cry at night until now. When will there be a cure for HIV? How long will I take this medicine? If I cannot be cured, if I die, who will take care of my daughter? She is HIV positive. Who will give her the medicine? My mother is getting older; will my brother’s wife take care of my daughter? This condition encourages me to go to the hospital to get my medicine” Female participant, Indonesia [38]. “I fear what will happen to them when I am not there in this world. I feel my kids are fatherless kids because of the disease, [and] I am a widow.” Female participant, India [34]. |

| “Yes, madam, every day I am very sad about myself. Because we cannot move freely with everyone, like regular people... At that time [when I was first diagnosed], I felt very bad about myself. I thought, ‘Why should I live this life?’….” Female participant, India [10]. “It is a disease that I would not ever have as I am a good woman and I am only a housewife with one sexual partner, my husband. So, I never thought that I would have HIV/AIDS and I was very shocked the first time I knew my HIV status” Female participant, Indonesia [37]. “I felt people didn’t want to talk to me because I had this disease. I felt embarrassed when I was walking on the street because I used to look so ugly. I was 27 and my weight was 27 kg [60 pounds]. My hair color was black, but I had lost all my hair and looked like a beggar. I felt that people would be afraid of me when they saw me. It was difficult for me to leave the house. I used to leave the house only once a month, to pick up my medication. It was like this for two years...” Female participant, India [10]. “I can’t go to the beauty shop. It makes me feel sad and rejected. … I can talk to my friend when I am sad or hopeless” Female participant, Thailand [45]. “I did not blame anyone for what happened to me. I blamed myself because I had this virus from my previous high-risk behaviors. I blamed myself because I did not listen to my mom’s advice. My mom had prohibited me from having a sexual relationship with my friend” Female participant, Indonesia [37]. |

| “My mental illness affects my physical health; [I] felt like committing suicide.” Another woman shared how mental illness and suicide had touched not only her own life, but that of her husband: “My husband died committing suicide because he too suffered mental illness. I also feel the same way.” Female participant, India [34]. “I feel like taking some sleeping pills or eat some things to end my life.” Female participant, India [34]. “We lived together as a joint family. When they knew about this disease, they [my family] kept away. At that time, I felt very bad, thinking that everyone was healthy. Why has God given me this disease?... They kept away, madam, I felt very bad thinking about how I got this disease. I cried a lot, madam… I felt like I was going to die 149 tomorrow. My husband and I felt horrible and thought about committing suicide. Only because of our children did we not kill ourselves. In our family, nobody is aware of this disease. I have been living with HIV now for 14 years.” Female participant, India [10]. |

| SOCIAL IMPACT OF HIV ON WLHIV AND THEIR FAMILIES | |

| Anticipated and perceived stigma and discrimination among WLHIV | “Well, I was afraid that they would dislike me because some people heard or saw the news about HIV and understood it while some people didn’t…I didn’t know which of them would accept it and I didn’t want to be bothered by it, so I didn’t tell and that was it.” Female participants, Thailand [42]. “I have not told anyone at work that I’m HIV positive for fear I might lose my job. Because I am afraid that if I tell them that I have HIV, they will remove me from my job. That’s why I did not tell anyone… People would not touch me [if they knew I was HIV-positive]. And they would not even talk in close proximity to an HIV-positive person... They were afraid that if they touch me, they would also get the disease.” Female participants, India [10]. “I thought people would think badly about me, they would say she doesn’t have a husband. She must have done wrong things. That’s the reason she got this. And I thought they would hate me. Because of this fear, I did not tell them. People in the community think that people who are HIV positive made bad choices and that is the reason they are HIV positive.” Female participants, India [10]. “I am afraid that people will rang kiat [discriminate] me. Everyone is the same, and they think the same about the illness. It does not matter how many thousand people have HIV/AIDS within the populations of more than 60 millions, I would say that only zero percent will accept people living with HIV/AIDS” Female participant, Thailand [41]. |

External stigma and discrimination against WLHIV

| “Don’t cook for us anymore and don’t use our utensils.” Female participant, Thailand [45]. “My father told me to get out of the house. …. For four years, I stayed with my family, in a room. Nobody touched me and nobody talked to me for four years.” Female participant, India [33]. “My mother treated me differently. When I was released from Gandhi Hospital, my parents took me back to their house. One day my mother gave me rice to eat, then my brother’s daughter asked me to feed her. When I was feeding her [with my hands], my mother came and said, “Why are you feeding her your rice?” She said that she would feed her herself. I told my mother that I had not already eaten from the same plate, and that is why I was feeding her. Otherwise, I would not feed her… Sometimes I think that because of my HIV status and my husband’s death, I have lots of problems and I often get fed up with my life. But I have to be alive for my children. I feel sad that everyone is happy, but I am unable to be happy with them... My mother’s sister also has the same feelings towards me. She told my family members to keep my plate, glass, soap—everything—separate. She would say, “Why you are always allowing her to be with you people?” I have suffered a lot this way.” Female participant, India [10]. “After my husband’s death, I lived at my parents’ house. My father, my mother treated me differently. They separated my utensils. They used black tape to mark my plates, spoons, and cups. It was to distinguish that they were mine. I had a small tray, two cups, two plates, two spoons and forks. When they were dirty, I had to clean them by myself using [brand] liquid soap” Female participant, Indonesia [38]. |

| “Since my husband died and I cannot work to provide food for my family-in-law, they treat me with a cold heart. I cannot live there anymore. My mother-in-law sold the house that my husband and I built because it was not yet registered in our names.” Female participant, India [40]. “Not only did they blame me, they started beating me! And a few days later, they threw me out of the house. They said ‘You do not have good character so you go away.” Female participant, India [33]. “I was separated from my child (by her sister-in-law). My child slept with her aunty. My eating utensils were given a sign. The relatives of my husband also said to my sisters-in-law: ‘the spoon she used should be separated, you can be infected’. They were nice in front me but felt disgusted about me at the back. They asked my sisters-in-law to chase me and my husband (her husband was HIV-negative) away from the house (the woman and her husband lived together with her sisters-in-law in the same house)” Female participant, Indonesia [12]. “Nine months after my husband’s death, they drove me out from his family house. I’m now renting a room in Denpasar with three of my children while the youngest is still with my parents-in-law” Female participant, Indonesia [37]. |

| “Everyone in the neighborhood knows. Stigma is big. My mother–in-law doesn’t care about me, only about my baby. Neighbors visited out of curiosity. Some kept a distance, used bad words, and asked, ‘‘How could an HIV-infected person become a parent?’’ Female participant, India [40]. “I got discrimination in the community where I lived before. If I had touched any foods, then people would not eat those foods. Some (community members) spread information that I am HIV-positive and gossiped about it. I experienced these for about two years” Female participant, Indonesia [12]. |

| “When they knew my HIV status, they shouted at me and did not allow me to sit, even when I was bleeding and weak. They asked other patients to keep away from me. Then they transferred me to a special room. When I gave birth, there was no staff with me.” Female participant, India [40]. “There were nurses who gossiped about my HIV status. They were scared to get close to me or touched me … There was a nurse who told people within the community that I am sick because of this (HIV). She spread information (about his HIV status) within our community that I get HIV” Female participant, Indonesia [12]. “The ANM and staff nurse threw the records on my face and asked me to go to JIPMER for delivery. During that time my membranes ruptured. So I went to JIPMER, throwing my records (in frustration) and delivered there without disclosing my HIV status.” Female participant, India [35]. |

| “At the beginning of my illness, my face turned black. I did not know about this illness and my husband had already died. I had to work to bring up my two children. But later on I could not do so because my face was black and I was very thin. I was much thinner than I am now. I was asked to leave my job. When I went to apply for any other job, no one took me in and this had an impact on my children.” Female participant, Thailand [41]. |

| “As most people would not know how we actually get HIV/AIDS, they rang kiat [discriminate] women like us. You don’t need to look that far. It is my own sister who has already accepted that I have got HIV. She says she does not rang kiat me, but she will be very careful about everything as she still thinks she might get it from me. Like, when she sleeps, she will get another piece of bed cloth to cover where she sleeps. She is very careful. Even water, she will buy her own. What I mean that even if an educated person like my sister is still like this, what about other people? When they know about my HIV status, they will rang kiat [discriminate] me for sure.” Female participant, Thailand [41]. “We (the woman and her husband who was also HIV-positive and had died from AIDS) were avoided by nearly all the family members of my husband because they were scared of getting HIV, they did not know how it is transmitted. They thought they would get it if they have physical contact with us. A relative of my husband was the one who spread this misleading information to all the family members of my husband, she told all of them this wrong knowledge, hence they were influenced by what she said. Families and neighbors here are very close to each other, so sensitive information like this (about HIV) can quickly spread and they can easily influence each other and believe it”. Female participant, Indonesia [12]. |

| “People in community tend to see this disease as rok mua [promiscuous disease]. As women, we can have only one partner or one husband. But, for those who have HIV/AIDS, people tend to see them as having too many partners and this is not good. They are seen as pu ying mai dee [bad woman who has sex with many men]. And they will be rang kiat more than men who have HIV/AIDS.” Female participant, Thailand [41]. “Social perceptions about HIV are very negative, a disease (infection) of people with negative behaviors, such as women who are sex workers, have multiple sex partners or non-marital sex… They perceive HIV as a disgrace for family. Such perceptions influence how other people look at or react towards HIV-positive people … To be honest, I feel uncomfortable with these perceptions”. Female participant, Indonesia [12]. “People have in their heads that HIV transmits because of free sex or sex work, hence many do not respect HIV-positive people. They think we (PLHIV) are immoral because we engage in those immoral behaviors. I can feel it if someone who knows about my (HIV) status and disdains or disrespects me”. Female participant, Indonesia [12]. |

Stigma and discrimination against HIV-affected family members

| “The day after I learned of my HIV-positive status, my younger sister-in-law escorted all our other family members to go to VCT [voluntary counselling and testing] to get blood tests. She boiled all our bowls and chopsticks. After that, she sold her house and moved away; she doesn’t want to live with my husband and me.” Female participant, India [17]. “People do not join us in eating and they discriminate against my children.” Female participant, Thailand [45]. |

| “My neighbour would not let her child play with my daughter.” Female participant, Thailand [45]. “Last year my son was at the second grade. He was often sick and had to go to hospital. The teacher told the other children not to play with him because he was sick. He was also isolated from his friends because the teacher placed him at a separate desk. I must stand this discrimination and still let my son go to school. I always warn him not to play with his classmates and not to scratch or bite them.” Female participant, Vietnam [39]. |

Family separation

| “I had 9 children, but 2 are already dead. I still have 7 children, but only 2 stay with me. When we [she and her husband] were seriously sick, we gave away our children, one to my sister-in-law, one to my sibling. I was at hospital for 8 months. I thought that I was about to die, so all my relatives took my children, one for each”. Female participant, Cambodia [18]. ‘‘Children are at the district and living with my brother in-law there’’ Female participant, Cambodia [18]. |

3.2.1. Psychological Impact of HIV on WLHIV

3.2.2. Social Impact of HIV on WLHIV and Their Families

Stigma and Discrimination against WLHIV

Stigma and Discrimination against HIV-Affected Family Members and Family Separation

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary of Findings

4.2. Discussion of Psychological and Social Impact of HIV on WLHIV and Their Families

4.3. Implications for Future Practices or Interventions

4.3.1. Addressing Stigma and Discrimination against WLHIV and Their Children

4.3.2. Addressing Psychological Challenges on WLHIV

4.4. Implication for Future Studies

4.5. Limitation of the Study

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- UNAIDS. UNAIDS Data Geneva, Switzerland: Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. Available online: https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/2020_aids-data-book_en.pdf (accessed on 20 December 2020).

- UNAIDS. Global HIV & AIDS Statistics—Fact Sheet. Geneva, Switzerland: The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. Available online: https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/fact-sheet (accessed on 5 November 2021).

- Ashaba, S.; Kaida, A.; Coleman, J.; Burns, B.F.; Dunkley, E.; O’Neil, K.; Kastner, J.; Sanyu, N.; Akatukwasa, C.; Bangsberg, D.R.; et al. Psychosocial challenges facing women living with HIV during the perinatal period in rural Uganda. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0176256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Halli, S.S.; Khan, C.G.H.; Moses, S.; Blanchard, J.; Washington, R.; Shah, I.; Isac, S. Family and community level stigma and discrimination among women living with HIV/AIDS in a high HIV prevalence district of India. J. HIV/AIDS Soc. Serv. 2017, 16, 4–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Local Burden of Disease HIV Collaborators. Mapping subnational HIV mortality in six Latin American countries with incomplete vital registration systems. BMC Med. 2021, 19, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Sartorius, B.; VanderHeide, J.D.; Yang, M.; Goosmann, E.A.; Hon, J.; Haeuser, E.; Cork, M.A.; Perkins, S.; Jahagirdar, D.; Schaeffer, L.E.; et al. Subnational mapping of HIV incidence and mortality among individuals aged 15–49 years in sub-Saharan Africa, 2000–2018: A modelling study. Lancet HIV 2021, 8, e363–e375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The World Bank. World Bank Country and Lending Groups. Available online: https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups#:~:text=%EF%BB%BF%EF%BB%BF%20For%20the%20current, those%20with%20a%20GNI%20per (accessed on 15 February 2022).

- Qin, S.; Tan, Y.; Lu, B.; Cheng, Y.; Nong, Y. Survey and analysis for impact factors of psychological distress in HIV-infected pregnant women who continue pregnancy. J. Matern.-Fetal Neonatal Med. 2018, 32, 3160–3167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruffell, S. Stigma kills! The psychological effects of emotional abuse and discrimination towards a patient with HIV in Uganda. BMJ Case Rep. 2017, 2017, bcr-2016-218024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azhar, S.V. HIV Stigma and Gender: A Mixed Methods Study of People Living with HIV in Hyderabad, India; ProQuest LLC: Livingston, NJ, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Cuca, Y.P.; Onono, M.; Bukusi, E.; Turan, J.M. Factors associated with pregnant women’s anticipations and experiences of HIV-related stigma in rural Kenya. AIDS Care 2012, 24, 1173–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fauk, N.; Hawke, K.; Mwanri, L.; Ward, P. Stigma and Discrimination towards People Living with HIV in the Context of Families, Communities, and Healthcare Settings: A Qualitative Study in Indonesia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fauk, N.K.; Ward, P.R.; Hawke, K.; Mwanri, L. HIV Stigma and Discrimination: Perspectives and Personal Experiences of Healthcare Providers in Yogyakarta and Belu, Indonesia. Front. Med. 2021, 8, 625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audet, C.M.; McGowan, C.C.; Wallston, K.A.; Kipp, A.M. Relationship between HIV Stigma and Self-Isolation among People Living with HIV in Tennessee. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e69564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Skinner, D.; Mfecane, S. Stigma, discrimination and the implications for people living with HIV/AIDS in South Africa. SAHARA J. 2004, 1, 157–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conserve, D.F.; Eustache, E.; Oswald, C.M.; Louis, E.; Scanlan, F.; Mukherjee, J.S.; Surkan, P.J. Maternal HIV illness and its impact on children’s well-being and development in Haiti. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2015, 24, 2779–2785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Manopaiboon, C.; Shaffer, N.; Clark, L.; Bhadrakom, C.; Siriwasin, W.; Chearskul, S.; Suteewan, W.; Kaewkungwal, J.; Bennetts, A.; Mastro, T.D. Impact of HIV on families of HIV-infected women who have recently given birth, Bangkok, Thailand. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. Hum. Retrovirol. 1998, 18, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Lewis, F.M.; Wojnar, D. Life changes in women Infected with HIV by their husbands: An interpretive phenomenological study. J. Assoc. Nurses AIDS Care 2015, 26, 580–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodney, P.; Ceesay, K.F.; Wilson, O.N. Addressing the Impact of HIV/AIDS on Women and Children in Sub-Saharan Africa: PEPFAR, the U.S. Strategy. Afr. Today 2010, 57, 64–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mugambi, J. The impact of HIV/AIDS on Kenyan rural women and the role of counseling. Int. Soc. Work 2006, 49, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falleiro, P.S.; Noronha, M.S. Economic Impact of HIV/AIDS on Women. J. Health Manag. 2012, 14, 495–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, D.A.; Austin, E.L.; Greenwell, L. Correlates of HIV-Related Stigma among HIV-Positive Mothers and Their Uninfected Adolescent Children. Women Health 2007, 44, 19–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conserve, D.F.; Eustache, E.; Oswald, C.M.; Louis, E.; King, G.; Scanlan, F.; Mukherjee, J.S.; Surkan, P.J. Disclosure and Impact of Maternal HIV+ Serostatus on Mothers and Children in Rural Haiti. Matern. Child Health J. 2014, 18, 2309–2315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mwangala, P.N.; Mabrouk, A.; Wagner, R.; Newton, C.R.J.C.; Abubakar, A.A. Mental health and well-being of older adults living with HIV in sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e052810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waldron, E.M.; Burnett-Zeigler, I.; Wee, V.; Ng, Y.W.; Koenig, L.J.; Pederson, A.B.; Tomaszewski, E.; Miller, E.S. Mental Health in Women Living With HIV: The Unique and Unmet Needs. J. Int. Assoc. Provid. AIDS Care 2021, 20, 2325958220985665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paudel, V.; Baral, K.P. Women living with HIV/AIDS (WLHA), battling stigma, discrimination and denial and the role of support groups as a coping strategy: A review of literature. Reprod. Health 2015, 12, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Rueda, S.; Mitra, S.; Chen, S.; Gogolishvili, D.; Globerman, J.; Chambers, L.; Wilson, M.; Logie, C.H.; Shi, Q.; Morassaei, S.; et al. Examining the associations between HIV-related stigma and health outcomes in people living with HIV/AIDS: A series of meta-analyses. BMJ Open 2016, 6, e011453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schardt, C.; Adams, M.B.; Owens, T.; Keitz, S.; Fontelo, P. Utilization of the PICO framework to improve searching PubMed for clinical questions. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2007, 7, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Forsythe, S.S.; McGreevey, W.; Whiteside, A.; Shah, M.; Cohen, J.; Hecht, R.; Bollinger, L.A.; Kinghorn, A. Twenty Years of Antiretroviral Therapy for People Living with HIV: Global Costs, Health Achievements, Economic Benefits. Health Aff. 2019, 38, 1163–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The EndNote Team. EndNote X9; Clarivate: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Joana Briggs Institute. Critical Appraisal Tools Australia: Joana Briggs Institute. 2017. Available online: http://joannabriggs.org/research/critical-appraisal-tools.html (accessed on 20 January 2020).

- Thomas, J.; Harden, A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2008, 8, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- De Souza, R. Women living with HIV: Stories of powerlessness and agency. Women’s Stud. Int. Forum 2010, 33, 244–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, N.; Nyamathi, A.M.; Sinha, S.; Carpenter, C.; Satyanarayana, V.; Ramakrishna, P.; Ekstrand, M. Women living with AIDS in rural Southern India: Perspectives on mental health and lay health care worker support. J. HIV/AIDS Soc. Serv. 2017, 16, 170–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Subramaniyan, A.; Sarkar, S.; Roy, G.; Lakshminarayanan, S. Experiences of HIV Positive Mothers from Rural South India during Intra-Natal Period. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2013, 7, 2203–2206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, B.; Nyamathi, A.; Swaminathan, S. Impact of HIV/AIDS on mothers in southern India: A qualitative study. AIDS Behav. 2009, 13, 989–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Halimatusa’diyah, L. Moral injury and the struggle for recognition of women living with HIV/AIDS in Indonesia. Int. Sociol. 2019, 34, 696–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, R.; Voss, J.; Woods, N.F.; John-Stewart, G.; Lowe, C.; Nurachmah, E.; Yona, S.; Muhaimin, T.; Boutain, D. A content analysis study: Concerns of Indonesian women infected with HIV by husbands who used intravenous drugs. J. Assoc. Nurses AIDS Care 2018, 29, 914–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chi, B.K.; Rasch, V.; Hȧnh, N.T.T.; Gammeltoft, T. Induced abortion among HIV-positive women in Northern Vietnam: Exploring reproductive dilemmas. Cult. Health Sex. 2010, 12, S41–S54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, T.A.; Oosterhoff, P.; Ngoc, Y.P.; Wright, P.; Hardon, A. Self-Help Groups Can Improve Utilization of Postnatal Care by HIV-Infected Mothers. J. Assoc. Nurses AIDS Care 2009, 20, 141–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liamputtong, P.; Haritavorn, N.; Kiatying-Angsulee, N. HIV and AIDS, stigma and AIDS support groups: Perspectives from women living with HIV and AIDS in central Thailand. Soc. Sci. Med. 2009, 69, 862–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathew, R.S.; Boonsuk, P.; Dandu, M.; Sohn, A.H. Experiences with stigma and discrimination among adolescents and young adults living with HIV in Bangkok, Thailand. AIDS Care 2019, 32, 530–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, X.; Wang, H.; He, X.; Wang, X. Stigmatization and Social Support of Pregnant Women with HIV or Syphilis in Eastern China: A Mixed-Method Study. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 764203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paxton, S.; Gonzales, G.; Uppakaew, K.; Abraham, K.K.; Okta, S.; Green, C.; Nair, K.S.; Merati, T.P.; Thephthien, B.; Marin, M.; et al. AIDS-related discrimination in Asia. AIDS Care 2005, 17, 413–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dane, B. Disclosure: The voices of Thai women living with HIV/AIDS. Int. Soc. Work 2002, 45, 185–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The United Nations. The Impact of AIDS; United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs/Population Division: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Earnshaw, V.A.; Chaudoir, S.R. From Conceptualizing to Measuring HIV Stigma: A Review of HIV Stigma Mechanism Measures. AIDS Behav. 2009, 13, 1160–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkington, K.S.; Robbins, R.N.; Bauermeister, J.A.; Abrams, E.J.; McKay, M.; Mellins, C.A. Mental Health in Youth Infected with and Affected by HIV: The Role of Caregiver HIV. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2010, 36, 360–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gamarel, K.E.; Kuo, C.C.; Boyes, M.E.; Cluver, L.D. The dyadic effects of HIV stigma on the mental health of children and their parents in South Africa. J. HIV/AIDS Soc. Serv. 2017, 16, 351–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Patel, S.N.; Wingood, G.M.; Kosambiya, J.K.; Mccarty, F.; Windle, M.; Yount, K.; Hennink, M. Individual and Interpersonal Characteristics that Influence Male-Dominated Sexual Decision-Making and Inconsistent Condom Use Among Married HIV Serodiscordant Couples in Gujarat, India: Results from the Positive Jeevan Saathi Study. AIDS Behav. 2014, 18, 1970–1980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Wojnar, D.; Lewis, F.M. Becoming a person with HIV: Experiences of Cambodian women infected by their spouses. Cult. Health Sex. 2016, 18, 198–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Lewis, F.M.; Wojnar, D. Culturally Embedded Risk Factors for Cambodian Husband-Wife HIV Transmission: From Women’s Point of View. J. Nurs. Sch. 2016, 48, 154–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fauk, N.K.; Merry, M.S.; Putra, S.; Sigilipoe, M.A.; Crutzen, R.; Mwanri, L. Perceptions among transgender women of factors associated with the access to HIV/AIDS-related health services in Yogyakarta, Indonesia. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0223904. [Google Scholar]

- Fauk, N.K.; Merry, M.S.; Siri, T.A.; Tazir, F.T.; Sigilipoe, M.A.; Tarigan, K.O.; Mwanri, L. Facilitators to Accessibility of HIV/AIDS-Related Health Services among Transgender Women Living with HIV in Yogyakarta, Indonesia. AIDS Res. Treat. 2019, 2019, 6045726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Devi, N.D. Women Living with HIV/AIDs in Manipur: Relations with Family and Neighbourhood. Indian J. Gend. Stud. 2016, 23, 324–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fauk, N.K.; Mwakinyali, S.E.; Putra, S.; Mwanri, L. The socio-economic impacts of AIDS on families caring for AIDS-orphaned children in Mbeya rural district, Tanzania. Int. J. Hum. Rights Health 2017, 10, 132–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Li, X.; Sherr, L. The impact of HIV/AIDS on children’s educational outcome: A critical review of global literature. AIDS Care 2012, 24, 993–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pufall, E.L.; Nyamukapa, C.; Eaton, J.W.; Campbell, C.; Skovdal, M.; Munyati, S.; Robertson, L.; Gregson, S. The impact of HIV on children’s education in eastern Zimbabwe. AIDS Care 2014, 26, 1136–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mahamboro, D.B.; Fauk, N.K.; Ward, P.R.; Merry, M.S.; Siri, T.A.; Mwanri, L. HIV Stigma and Moral Judgement: Qualitative Exploration of the Experiences of HIV Stigma and Discrimination among Married Men Living with HIV in Yogyakarta. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Stangl, A.L.; Earnshaw, V.A.; Logie, C.H.; Van Brakel, W.; Simbayi, L.C.; Barré, I.; Dovidio, J.F. The Health Stigma and Discrimination Framework: A global, crosscutting framework to inform research, intervention development, and policy on health-related stigmas. BMC Med. 2019, 17, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mbonu, N.C.; Borne, B.V.D.; De Vries, N.K. Stigma of People with HIV/AIDS in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Literature Review. J. Trop. Med. 2009, 2009, 145891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Khawcharoenporn, T.; Srirach, C.; Chunloy, K. Educational Interventions Improved Knowledge, Attitude, and Practice to Prevent HIV Infection among HIV-Negative Heterosexual Partners of HIV-Infected Persons. J. Int. Assoc. Prov. AIDS Care 2020, 19, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lalonde, B.; Uldall, K.K.; Huba, G.J.; Panter, A.T.; Zalumas, J.; Wolfe, L.R.; Rohweder, C.; Colgrove, J.; Henderson, H.; German, V.F.; et al. Impact of HIV/AIDS education on health care provider practice: Results from nine grantees of the Special Projects of National Significance Program. Eval. Health Prof. 2002, 25, 302–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Wu, S.; Wu, Z.; Sun, S.; Cui, H.; Jia, M. Understanding Family Support for People Living with HIV/AIDS in Yunnan, China. AIDS Behav. 2006, 10, 509–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lo, Y.-R.; Chu, C.; Ananworanich, J.; Excler, J.-L.; Tucker, J. Stakeholder Engagement in HIV Cure Research: Lessons Learned from Other HIV Interventions and the Way Forward. AIDS Patient Care STDs 2015, 29, 389–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cornu, C.; Attawell, K. The Involvement of People Living with HIV/AIDS in Community-based Prevention, Care and Support Programs in Developing Countries: A Multi-Country Diagnostic Study; International HIV/AIDS Alliance: London, UK, 2003; Available online: https://www.popcouncil.org/uploads/pdfs/horizons/plha4cntryrprt.pdf (accessed on 20 January 2020).

- Morolake, O.; Stephens, D.; Welbourn, A. Greater involvement of people living with HIV in health care. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2009, 12, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Berg, R.C.; Page, S.; Øgård-Repål, A. The effectiveness of peer-support for people living with HIV: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0252623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mmbaga, E.J.; Leyna, G.H.; Leshabari, M.T.; Tersbøl, B.; Lange, T.; Makyao, N.; Moen, K.; Meyrowitsch, D.W. Effectiveness of health care workers and peer engagement in promoting access to health services among population at higher risk for HIV in Tanzania (KPHEALTH): Study protocol for a quasi experimental trial. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2019, 19, 801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henderson, H.; German, V.F.; Panter, A.T.; Huba, G.J.; Rohweder, C.; Zalumas, J.; Wolfe, L.; Uldall, K.K.; Lalonde, B.; Henderson, R.; et al. Systems Change Resulting from HIV/AIDS Education and Training. Eval. Health Prof. 1999, 22, 405–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brennan, A.; Browne, J.P.; Horgan, M. A systematic review of health service interventions to improve linkage with or retention in HIV care. AIDS Care 2014, 26, 804–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yator, O.; Mathai, M.; Vander Stoep, A.; Rao, D.; Kumar, M. Risk factors for postpartum depression in women living with HIV attending prevention of mother-to-child transmission clinic at Kenyatta National Hospital, Nairobi. AIDS Care 2016, 28, 884–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chippindale, S.; French, L. HIV counselling and the psychosocial management of patients with HIV or AIDS. BMJ Case Rep. 2001, 322, 1533–1535. [Google Scholar]

- Schweitzer, A.-M.; Mizwa, M.B.; Ross, M. Psychosocial Aspects of HIV/AIDS: Adults; Schweitzer, A.-M., Mizwa, M.B., Ross, M., Eds.; HIV Curriculum for the Health Professional; Baylor College of Medicine: Houston, TX, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Vigliotti, V.; Taggart, T.; Walker, M.; Kusmastuti, S.; Ransome, Y. Religion, faith, and spirituality influences on HIV prevention activities: A scoping review. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0241737. [Google Scholar]

- Burchardt, M. Subjects of Counselling: Religion, HIV/AIDS and the Management of Everyday Life in South Africa; Becker, F., Geissler, W., Eds.; AIDS and Religious Practice in Africa; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2009; pp. 333–358. [Google Scholar]

- Stynes, R.; Lipp, J.; Minichiello, V. HIV and AIDS and “family” counselling: A systems and developmental perspective. Couns. Psychol. Q. 1996, 9, 131–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.J.; Li, X.; Qiao, S.; Zhou, Y. Family relations in the context of HIV/AIDS in Southwest China. AIDS Care 2016, 28, 1261–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, M.G.; Husbands, W.; Makoroka, L.; Rueda, S.; Greenspan, N.R.; Eady, A.; Dolan, L.-A.; Kennedy, R.; Cattaneo, J.; Rourke, S. Counselling, Case Management and Health Promotion for People Living with HIV/AIDS: An Overview of Systematic Reviews. AIDS Behav. 2013, 17, 1612–1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Author/Year | Study Location | Study Design/Study Aim | Number of Participants/Type of Participants | Analysis | Main Themes of the Impact HIV on WLHIV and Their Families |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Azhar, 2018 [10] | India | (i) Qualitative design (ii) Methods:

| (i) 16 WLHIV (ii) Marital status:

| Thematic analysis | The impact of HIV on WLHIV (i) Psychological impact

|

| 2. Chi, et al., 2010 [39] | Vietnam | (i) Qualitative design (ii) Methods:

| (i) 13 WLHIV (ii) Marital status:

| Thematic analysis | The impact of HIV on WLHIV (i) Psychological impact

(i) External stigma and discrimination against children at school

|

| 3. de Souza, 2010 [33] | India | (i) Qualitative design (ii) Methods:

| (i) Two WLHIV (ii) Marital status:

| Content analysis | The impact of HIV on WLHIV (i) External stigma and discrimination

|

| 4. Fauk, et al., 2021 [12] | Indonesia | (i) Qualitative design (ii) Methods:

| (i) 52 WLHIV and 40 MLHIV (ii) Marital status:

| Thematic analysis | The impact of HIV on WLHIV (i) Externa stigma and discrimination

|

| 5. Halli, et al., 2017 [4] | India | (i) Quantitative design:

| (i) 633 married WLHIV (ii) Marital status:

| Bivariate analysis and multivariate logistic regression models | The impact of HIV on WLHIV (i) Externa stigma and discrimination

|

| 6. Halimatusa’diah, 2019 [37] | Indonesia | (i) Qualitative design (ii) Methods:

| (i) 33 WLHIV (ii) Marital status:

| Thematic analysis | The impact of HIV on WLHIV (i) Psychological impacts

|

| 7. Ismail, et al., 2018 [38] | Indonesia | (i) Qualitative design (ii) Methods:

| (i) 12 WLHIV (ii) Marital status:

| Content analysis | The impact of HIV on WLHIV (i) Psychological impacts

(ii) External stigma and discrimination

|

| 8. Liamputtong, et al., 2009 [41] | Indonesia | (i) Qualitative design (ii) Methods:

| (i) 26 WLHIV (ii) Marital status:

| Thematic analysis | The impact of HIV on WLHIV (i) Anticipated stigma

|

| 9. Mathew, et al., 2019 [42] | Thailand | (i) Qualitative design (ii) Methods:

| (i) 14 WLHIVs and 9 MLHIV. (ii) Marital status:

Only the results about the impact of HIV on the female participants are included. | Thematic analysis | The impact of HIV on WLHIV (i) Perceived stigma

|

| 10. Nguyen, et al., 2009 [40] | Vietnam | (i) Qualitative design (ii) Methods:

| (i) 30 married WLHIV (ii) Marital status:

| Thematic analysis | The impact of HIV on WLHIV (i) External stigma and discrimination

The impact of HIV on families of WLHIV (i) External stigma and discrimination

|

| 11. Paxton, et al., 2005 [44] | India, Indonesia, Thailand, the Philippines | (i) Quantitative design:

| (i) 764 PLHIV in four countries (India 302; Indonesia 42; Thailand 338; the Philippines 82) (ii) 348 respondents were female:

(iv) Participants’ age:

Only results about WLHIV were used. | Chi square test | The impact of HIV on WLHIV (i) External stigma and discrimination

The impact of HIV on families of WLHIV (i) Impact on children’s education

|

| 12. Qin, 2018 [8] | China | (i) Quantitative design:

| (i) 194 pregnant WLHIV (ii) Marital status:

| Multiple linear regression analysis | The impact of HIV on WLHIV (i) Psychological impact

|

| 13. Srivastava, et al., 2017 [34] | India | (i) Qualitative design (ii) Methods:

| (i) 16 WLHIV who were mothers (ii) Marital status:

| Content analysis | The impact of HIV on WLHIV (i) Psychological impact

|

| 14. Subramaniyan, et al., 2013 [35] | India | (i) Qualitative design (ii) Methods:

| (i) 21 WLHIV who were mothers (ii) Marital status:

| Content analysis | The impact of HIV on WLHIV (i) External stigma and discrimination

|

| 15. Thomas, et al., 2009 [36] | India | (i) Qualitative design (ii) Methods:

| (i) 60 WLHIV (ii) Marital status:

| Content analysis | The impact of HIV on WLHIV (i) External stigma and discrimination

|

| 16. Zhang, et al., 2022 [43] | China | (i) Qualitative and quantitative (mixed-method) design (ii) Methods:

| (i) 93 WLHIV (ii) 355 women living with syphilis (iii) Marital status:

| Descriptive analysis; t-tests; Chi Square tests; Content analysis | The impact of HIV on WLHIV (i) Psychological impacts

(ii) External stigma and discrimination

|

| 17. Yang, 2015 [18] | Cambodia | (i) Qualitative design (ii) Methods:

| (i) 15 WLHIV (ii) Marital status:

| (i) thematic analysis, (ii) analysis of episodes, and (iii) identification of paradigm cases | The impact of HIV on families of WLHIV (i) Family separation

|

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fauk, N.K.; Mwanri, L.; Hawke, K.; Mohammadi, L.; Ward, P.R. Psychological and Social Impact of HIV on Women Living with HIV and Their Families in Low- and Middle-Income Asian Countries: A Systematic Search and Critical Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 6668. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19116668

Fauk NK, Mwanri L, Hawke K, Mohammadi L, Ward PR. Psychological and Social Impact of HIV on Women Living with HIV and Their Families in Low- and Middle-Income Asian Countries: A Systematic Search and Critical Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(11):6668. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19116668

Chicago/Turabian StyleFauk, Nelsensius Klau, Lillian Mwanri, Karen Hawke, Leila Mohammadi, and Paul Russell Ward. 2022. "Psychological and Social Impact of HIV on Women Living with HIV and Their Families in Low- and Middle-Income Asian Countries: A Systematic Search and Critical Review" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 11: 6668. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19116668

APA StyleFauk, N. K., Mwanri, L., Hawke, K., Mohammadi, L., & Ward, P. R. (2022). Psychological and Social Impact of HIV on Women Living with HIV and Their Families in Low- and Middle-Income Asian Countries: A Systematic Search and Critical Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(11), 6668. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19116668