Is the Association between Suicide and Unemployment Common or Different among the Post-Soviet Countries?

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data

2.2. Statistical Analysis

2.3. Interpretation

3. Results

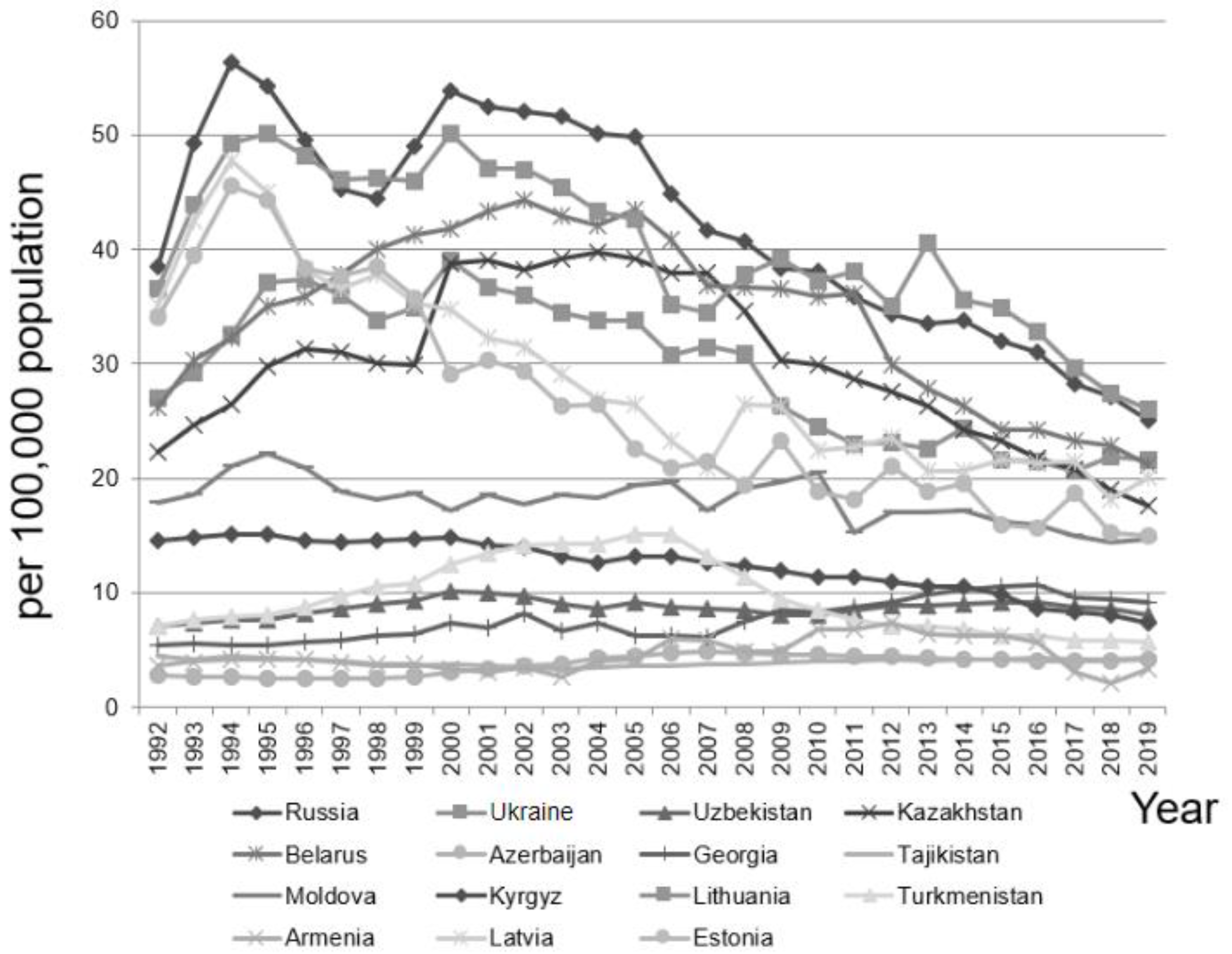

3.1. The Annual Suicide Rate and Unemployment Rate in the 15 Post-Soviet Countries during the 28-Year Period 1992–2019

3.2. The Correlation between the Suicide Rate and the Unemployment Rate in the Post-Soviet Countries in 1992–2019

3.3. The Association between the Suicide Rate and the Unemployment Rate in the Populations of the 15 Post-Soviet Countries

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization (WHO). Suicide Worldwide in 2019: Global Health Estimates. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/rest/bitstreams/1350975/retrieve (accessed on 26 March 2022).

- The World Bank Group. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/country/XO (accessed on 22 December 2021).

- Soviet Union. Available online: https://www.britannica.com/place/Soviet-Union (accessed on 5 March 2022).

- WHO. Suicide in the World: Global Health Estimates. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/326948 (accessed on 26 March 2022).

- Värnik, A.; Wasserman, D. Suicides in the former Soviet republics. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 1992, 86, 76–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasserman, D.; Varnik, A.; Dankowicz, M. Regional differences in the distribution of suicide in the former Soviet Union during perestroika, 1984–1990. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. Suppl. 1998, 394, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silagadze, A. Post-Soviet paradoxes of unemployment rate. Bull. Georgian Natl. Acad. Sci. 2017, 11, 136–141. [Google Scholar]

- Vahabov, N.V.; Asadov, B.M. Prevalence of complicated suicides among women in the Azerbaijan Republic. Meditsinskie Nov. 2017, 10, 48–51. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Rozanov, V.A. Suicides, psycho-social stress and alcohol consumption in the countries of the former USSR. Suicidology 2012, 4, 28–40. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Razvodovsky, Y.E. Alcohol and suicides in Russia, Ukraine and Belarus: A comparative analysis of trends. Suicidology 2016, 7, 3–10. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Paresashvili, N.; Maisuradze, T. Unemployment as the main challenge in Georgia. In RTU 59th International Scientific Conference on Economics and Entrepreneurship SCEE’2018; Riga Technical University: Riga, Latvia, 2018; pp. 72–78. [Google Scholar]

- Abesadze, N.; Paresashvili, N. Gender aspects of youth employment in Georgia. Ecoforum 2018, 7, 14. Available online: https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/236086812.pdf (accessed on 2 June 2022).

- Inoue, K.; Seksenbayev, N.; Chaizhunusova, N.; Moldagaliyev, T.; Ospanova, N.; Tokesheva, S.; Zhunussov, Y.T.; Takeichi, N.; Noso, Y.; Hoshi, M.; et al. An exploration of the labor, financial, and economic factors related to suicide in the Republic of Kazakhstan. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 6992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbulaev, N.; Aliyeva, B. Gender and economic growth: Is there a correlation? The example of Kyrgyzstan. Cogent Econ. Financ. 2020, 8, 1758007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molchanova, E.; Galako, T. Suicides in the Kyrgyz Republic: Discrepancies in different types of official statistics. Eur. Psychiatry 2017, 41, S890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNICEF. Situation Analysis on Adolescent and Youth Suicides and Attempted Suicides in Kyrgyzstan. 2020. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/kyrgyzstan/reports/situation-analysis-adolescent-and-youth-suicides-and-attempted-suicides-kyrgyzstan (accessed on 26 March 2022).

- Ferretti, F.; Coluccia, A. Socio-economic factors and suicide rates in European Union countries. Leg. Med. 2009, 11 (Suppl. 1), S92–S94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rancans, E.; Salander Renberg, E.; Jacobsson, L. Major demographic, social and economic factors associated to suicide rates in Latvia 1980–1998. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2001, 103, 275–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yur’Yev, A.; Värnik, A.; Värnik, P.; Sisask, M.; Leppik, L. Employment status influences suicide mortality in Europe. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2012, 58, 62–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalediene, R.; Petrauskiene, J. Inequalities in daily variations of deaths from suicide in Lithuania: Identification of possible risk factors. Suicide Life Threat. Behav. 2004, 34, 138–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalediene, R.; Starkuviene, S.; Petrauskiene, J. Seasonal patterns of suicides over the period of socio-economic transition in Lithuania. BMC Public Health 2006, 6, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- International Labour Organization. ILO Global Employment Trends 2010—Unemployment Reaches Highest Level on Record in 2009. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/global/about-the-ilo/newsroom/news/WCMS_120465/lang--en/index.htm (accessed on 26 March 2022).

- Polozhiy, B.S. Dynamics of suicide rates in European post-socialist countries. Russ. J. Psychiatry 2015, 1, 39–42. [Google Scholar]

- Kõlves, K.; Milner, A.; Värnik, P. Suicide rates and socioeconomic factors in Eastern European countries after the collapse of the Soviet Union: Trends between 1990 and 2008. Sociol. Health Illn. 2013, 6, 956–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pridemore, W.A. Heavy drinking and suicide in Russia. Soc. Forces 2006, 85, 413–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ibrogimova, A.U. Application of foreign experience in improving reproduction of the labor force to reduce the level of unemployment in the Republic of Tajikistan. Sci. J. 2018, 29, 55–59. [Google Scholar]

- Sharopova, N.M.; Sharipov, T.; Tursunov, R.A. Sociodemographic and ethnocultural aspects of suicide in the Republic of Tajikistan. Avicenna Bull. 2014, 3, 86–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savani, S.; Gearing, R.E.; Frantsuz, Y.; Sozinova, M. Suicide in Central Asia. Suicidology 2020, 11, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lester, D. Suicide in post-Soviet Central Asia. Cent. Asian Surv. 1999, 18, 121–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razvodovsky, Y.E.; Kandrychyn, S.V. Suicides and mortality from tuberculosis before and after dissolution of USSR: The trends analysis. Suicidology 2017, 3, 70–77, (In Russian Abstract in English). [Google Scholar]

- Saidova, M.K. Youth unemployment in the labor market of Uzbekistan: Problems and some ways of solution. Econ. Financ. 2019, 9, 43–47. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Värnik, A. Suicide in Estonia. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 1991, 84, 229–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kõlves, K.; Tran, U.; Voracek, M. Knowledge about suicide and local suicide prevalence: Comparison of Estonia and Austria. Percept. Mot. Ski. 2007, 105, 3–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motohashi, Y. Suicide in Japan. Lancet 2012, 379, 1282–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.; Cho, Y. Does unstable employment have an association with suicide rates among the young? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yamasaki, A.; Araki, S.; Sakai, R.; Yokoyama, K.; Voorhees, A.S. Suicide mortality of young, middle-aged and elderly males and females in Japan for the years 1953–1996: Time series analysis for the effects of unemployment, female labour force, young and aged population, primary industry and population density. Ind. Health 2008, 46, 541–549, Erratum in Ind. Health 2009, 47, 343–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pompili, M.; Innamorati, M.; Di Vittorio, C.; Baratta, S.; Masotti, V.; Badaracco, A.; Wong, P.; Lester, D.; Yip, P.; Girardi, P.; et al. Unemployment as a risk factor for completed suicide: A psychological autopsy study. Arch. Suicide Res. 2014, 18, 181–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Health Data Exchange. Available online: http://ghdx.healthdata.org/gbd-results-tool?params = gbd-api-2019-permalink/338bb07b05a559965e5ef81b7bf31d69 (accessed on 1 September 2021).

- GLOBAL NOTE. Available online: https://www.globalnote.jp/post-7521.html (accessed on 31 August 2021).

- Inoue, K.; Tanii, H.; Kaiya, H.; Abe, S.; Nishimura, Y.; Masaki, M.; Okazaki, Y.; Nata, M.; Fukunaga, T. The correlation between unemployment and suicide rates in Japan between 1978 and 2004. Leg. Med. 2007, 9, 139–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Córdoba-Doña, J.A.; San Sebastián, M.; Escolar-Pujolar, A.; Martínez-Faure, J.E.; Gustafsson, P.E. Economic crisis and suicidal behaviour: The role of unemployment, sex and age in Andalusia, southern Spain. Int. J. Equity Health 2014, 13, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Errico, A.; Piccinelli, C.; Sebastiani, G.; Ricceri, F.; Sciannameo, V.; Demaria, M.; Di Filippo, P.; Costa, G. Unemployment and mortality in a large Italian cohort. J. Public Health 2021, 43, 361–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordt, C.; Warnke, I.; Seifritz, E.S.; Kawohl, W. Modelling suicide and unemployment: A longitudinal analysis covering 63 countries, 2000–2011. Lancet Psychiatry 2015, 2, 239–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fountoulakis, K.N. Employment insecurity, mental health and suicide. Psychiatriki 2017, 28, 259–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Oexle, N.; Waldmann, T.; Staiger, T.; Xu, Z.; Rüsch, N. Mental illness stigma and suicidality: The role of public and individual stigma. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 2018, 27, 169–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mérida-López, S.; Extremera, N.; Quintana-Orts, C.; Rey, L. Does emotional intelligence matter in tough times? A moderated mediation model for explaining health and suicide risk amongst short- and long-term unemployed adults. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Japan Institute for Labour Policy and Training. Tables 4–7: Definitions of unemployment. In Databook of International Labour Statistics 2011; Japan Institute for Labour Policy and Training: Tokyo, Japan, 2011; Volume 1, pp. 146–147. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Miyajima, T. Suicide Theory; Durkheim, Translator; Chuokoron Shinsha Inc.: Tokyo, Japan, 2005; Volume 17, pp. 9–560. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

| Total Population r-Value, p-Value | Males r-Value, p-Value | Females r-Value, p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Armenia | 0.425, 0.024 * | 0.436, 0.021 * | 0.382, 0.045 * |

| Azerbaijan | −0.359, 0.061 | −0.340, 0.077 | −0.382, 0.045 * |

| Belarus | 0.468, 0.012 * | 0.452, 0.016 * | 0.502, 0.007 ** |

| Estonia | 0.170, 0.387 | 0.198, 0.314 | 0.059, 0.765 |

| Georgia | 0.709, 2.5 × 10−5 *** | 0.712, 2.2 × 10−5 *** | 0.536, 0.003 ** |

| Kazakhstan | 0.565, 0.002 ** | 0.572, 0.001 ** | 0.490, 0.008 ** |

| Kyrgyzstan | −0.075, 0.703 | −0.012, 0.952 | −0.419, 0.026 * |

| Latvia | 0.598, 7 × 10−4 *** | 0.630, 3.23 × 10−4 *** | 0.492, 0.008 ** |

| Lithuania | 0.688, 5.2 × 10−5 *** | 0.689, 5 × 10−5 *** | 0.677, 7.6 × 10−5 *** |

| Moldova | 0.377, 0.048 * | 0.453, 0.015 * | 0.114, 0.563 |

| Russia | 0.647, 1.98 × 10−4 *** | 0.645, 2.14 × 10−4 *** | 0.633, 3 × 10−4 *** |

| Tajikistan | −0.701, 3.3 × 10−4 *** | −0.659, 1.37 × 10−4 *** | −0.466, 0.012 * |

| Turkmenistan | 0.598, 7 × 10−4 *** | 0.625, 3.8 × 10−4 *** | 0.352, 0.066 |

| Ukraine | 0.096, 0.628 | 0.158, 0.421 | −0.179, 0.361 |

| Uzbekistan | 0.492, 0.008 ** | 0.750, 4 × 10−6 *** | −0.394, 0.038 * |

| Total R2-Value p-Value | Males R2-Value p-Value | Females R2-Value p-Value | Total y= | Males y= | Females y= | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Armenia | 0.181 <0.05 * | 0.190 <0.05 * | 0.146 <0.05 * | 0.1281x + 2.940 | 0.1703x + 4.792 | 0.0965x + 1.178 |

| Azerbaijan | 0.129 >0.05 | 0.116 >0.05 | 0.146 <0.05 * | −0.1263x + 4.592 | −0.1921x + 7.279 | −0.5302x + 1.911 |

| Belarus | 0.219 <0.05 * | 0.204 <0.05 * | 0.252 <0.01 ** | 0.7187x + 27.691 | 1.3038x + 48.977 | 0.1729x + 9.279 |

| Estonia | 0.029 >0.05 | 0.039 >0.05 | 0.003 >0.05 | 0.4963x + 22.018 | 0.9978x + 36.478 | 0.0668x + 9.386 |

| Georgia | 0.502 <0.001 *** | 0.507 <0.001 *** | 0.287 <0.01 ** | 0.2928x + 3.543 | 0.5427x + 5.318 | 0.0554x + 2.047 |

| Kazakhstan | 0.319 <0.01 ** | 0.327 <0.01 ** | 0.240 <0.01 ** | 1.1148x + 21.601 | 2.0690x + 35.601 | 0.2409x + 8.420 |

| Kyrgyzstan | 0.006 >0.05 | 1 × 10−4 >0.05 | 0.175 <0.05 * | −0.0860x + 13.019 | −0.0232x + 20.399 | −0.1686x + 5.981 |

| Latvia | 0.358 <0.001 *** | 0.397 <0.001 *** | 0.242 <0.01 ** | 1.1521x + 14.278 | 1.9729x + 25.338 | 0.4349x + 5.058 |

| Lithuania | 0.473 <0.001 *** | 0.475 <0.001 *** | 0.458 <0.001 *** | 1.0742x + 28.054 | 1.8486x + 49.551 | 0.3729x + 9.637 |

| Moldova | 0.142 <0.05 * | 0.205 <0.05 * | 0.013 >0.05 | 0.3608x + 15.790 | 0.6846x + 26.950 | 0.0765x + 5.420 |

| Russia | 0.419 <0.001 *** | 0.415 <0.001 *** | 0.401 <0.001 *** | 2.4568x + 23.733 | 4.4152x + 41.477 | 0.6895x + 8.673 |

| Tajikistan | 0.491 <0.001 *** | 0.434 <0.001 *** | 0.217 <0.05 * | −0.0760x + 4.840 | −0.1013x + 6.611 | −0.0522x + 3.073 |

| Turkmenistan | 0.358 <0.001 *** | 0.390 <0.001 *** | 0.124 >0.05 | 0.5723x + 5.982 | 1.0602x + 8.582 | 0.0915x + 3.486 |

| Ukraine | 0.009 >0.05 | 0.025 >0.05 | 0.032 >0.05 | 0.2202x + 27.747 | 0.6464x + 47.640 | −0.1529x + 10.578 |

| Uzbekistan | 0.242 <0.01 ** | 0.562 <0.001 *** | 0.155 <0.05 * | 0.1245x + 7.752 | 0.3452x + 10.337 | −0.0856x + 5.147 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Seksenbayev, N.; Inoue, K.; Toleuov, E.; Akkuzinova, K.; Karimova, Z.; Moldagaliyev, T.; Ospanova, N.; Chaizhunusova, N.; Dyussupov, A. Is the Association between Suicide and Unemployment Common or Different among the Post-Soviet Countries? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 7226. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19127226

Seksenbayev N, Inoue K, Toleuov E, Akkuzinova K, Karimova Z, Moldagaliyev T, Ospanova N, Chaizhunusova N, Dyussupov A. Is the Association between Suicide and Unemployment Common or Different among the Post-Soviet Countries? International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(12):7226. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19127226

Chicago/Turabian StyleSeksenbayev, Nursultan, Ken Inoue, Elaman Toleuov, Kamila Akkuzinova, Zhanna Karimova, Timur Moldagaliyev, Nargul Ospanova, Nailya Chaizhunusova, and Altay Dyussupov. 2022. "Is the Association between Suicide and Unemployment Common or Different among the Post-Soviet Countries?" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 12: 7226. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19127226