Effects of a Social and Emotional Competence Enhancement Program for Adolescents Who Bully: A Quasi-Experimental Design

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design

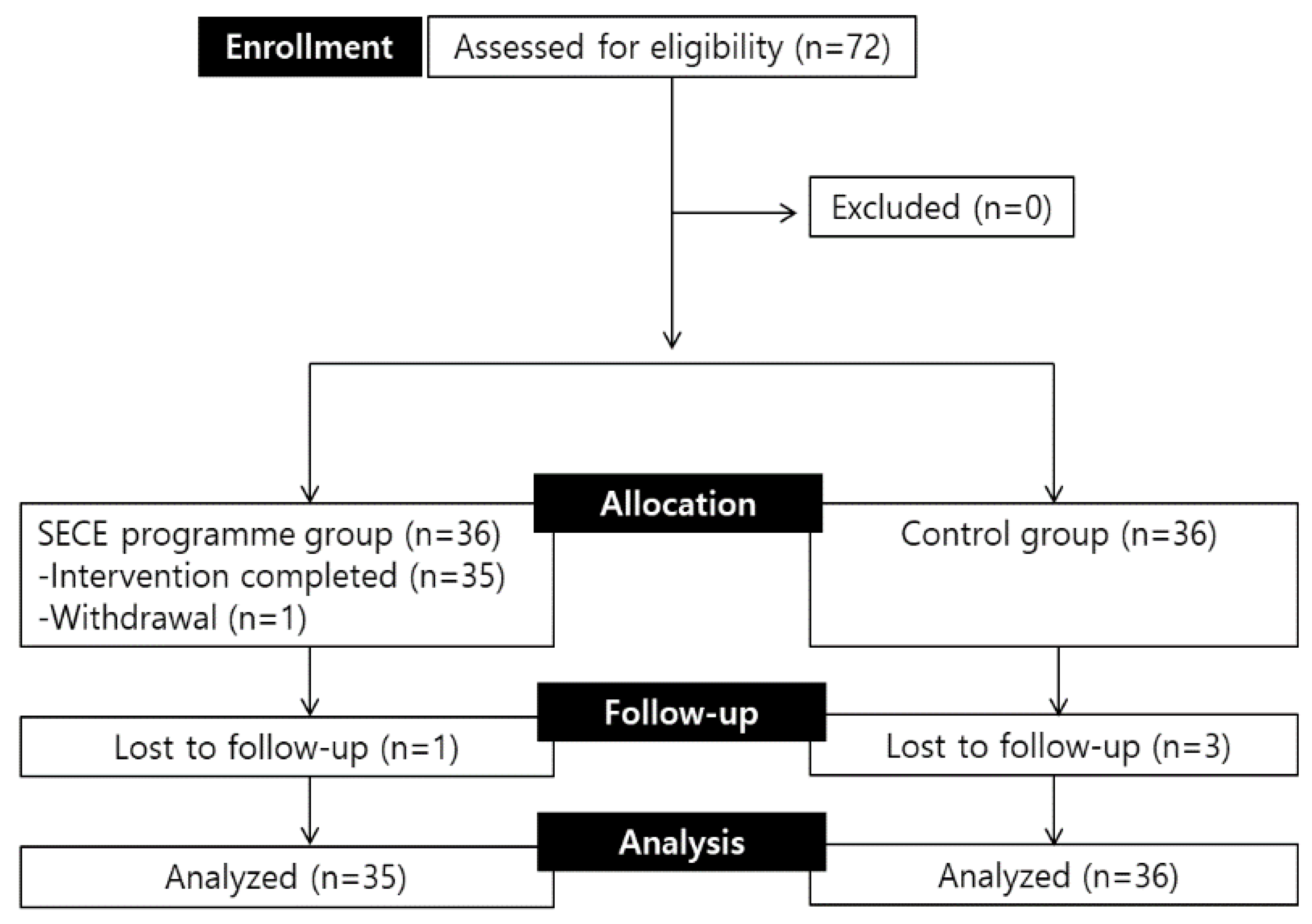

2.2. Participants

2.3. Procedures and Data Collection

2.4. Ethical Considerations

2.5. Intervention

2.6. Outcome Measures

2.6.1. Social and Emotional Competence

2.6.2. School Bullying Behavior

2.6.3. Mental Health

2.6.4. General Characteristics

2.7. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Homogeneity Verification for General Characteristics and Dependent Variables

3.2. Verification of the SECE Program’s Effects

3.2.1. Social and Emotional Competence

3.2.2. School Bullying Behavior

3.2.3. Mental Health

4. Discussion

4.1. Strength of the SECE Program

4.2. Effects of the Intervention on Social and Emotional Competence

4.3. Effects of the Intervention on School Bullying Behavior

4.4. Effects of the Intervention on Mental Health

4.5. Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dupper, D.R. School Bullying: New Perspectives on A Growing Problem; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huddleston, A. The bully, the bullied and the bystander: From pre-school to high school-How parents and teachers can help break the cycle of violence. Can. J. Public Health 2004, 95, 155. [Google Scholar]

- Sourander, A.; Jensen, P.; Ronning, J.A.; Niemela, S.; Helenius, H.; Sillanmaki, L.; Kumpulainen, K.; Piha, J.; Tamminen, T.; Moilanen, I. What is the early adulthood outcome of boys who bully or are bullied in childhood? The Finnish “From a Boy to a Man” study. Pediatrics 2007, 120, 397–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sigurdson, J.F.; Wallander, J.; Sund, A.M. Is involvement in school bullying associated with general health and psychosocial adjustment outcomes in adulthood? Child Abus. 2014, 38, 1607–1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Copeland, W.E.; Wolke, D.; Angold, A.; Costello, E.J. Adult psychiatric outcomes of bullying and being bullied by peers in childhood and adolescence. JAMA Psychiatry 2013, 70, 419–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ttofi, M.M.; Farrington, D.P.; Lösel, F.; Loeber, R. The predictive efficiency of school bullying versus later offending: A systematic/meta-analytic review of longitudinal studies. Crim. Behav. Ment. Health 2011, 21, 80–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhang, S.-Y.; Yoo, H.-I.K.; Kim, J.-H.; Kim, B.-S.; Lee, Y.-S.; Ahn, D.-H.; Suh, D.-S.; Cho, S.-C.; Hwang, J.-W.; Bahn, G.-H. Victims of bullying among Korean adolescents: Prevalence and association with psychopathology evaluated using the adolescent mental health and problem behavior screening questionnaire-II standardization study data. J. Korean Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2012, 23, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olweus, D. A useful evaluation design, and effects of the Olweus Bullying Prevention Program. Psychol. Crime Law 2005, 11, 389–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.D.; Schneider, B.H.; Smith, P.K.; Ananiadou, K. The effectiveness of whole-school antibullying programs: A synthesis of evaluation research. Sch. Psychol. Rev. 2004, 33, 547–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espelage, D.L.; Low, S.; Van Ryzin, M.J.; Polanin, J.R. Clinical trial of second step middle school program: Impact on bullying, cyberbullying, homophobic teasing, and sexual harassment perpetration. Sch. Psychol. Rev. 2015, 44, 464–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durlak, J.A.; Weissberg, R.P.; Dymnicki, A.B.; Taylor, R.D.; Schellinger, K.B. The impact of enhancing students’ social and emotional learning: A meta-analysis of school-based universal interventions. Child Dev. 2011, 82, 405–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, R.D.; Oberle, E.; Durlak, J.A.; Weissberg, R.P. Promoting positive youth development through school-based social and emotional learning interventions: A meta-analysis of follow-up effects. Child Dev. 2017, 88, 1156–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, S.J.; Lipsey, M.W. The effects of school-based social information processing interventions on aggressive behavior, part I: Universal programs. Campbell Syst. Rev. 2006, 2, 1–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrington, D.P.; Ttofi, M.M. School-based programs to reduce bullying and victimization. Campbell Syst. Rev. 2009, 5, i-148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A.; Houghton, S.; Forrest, K.; McCarthy, M.; Sanders-O’Connor, E. Who benefits most? Predicting the effectiveness of a social and emotional learning intervention according to children’s emotional and behavioural difficulties. Sch. Psychol. Int. 2020, 41, 197–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, M.; Wirtz, S.; Allroggen, M.; Scheithauer, H. Intervention and Therapy for Perpetrators and Victims of Bullying: A Systematic Review/Intervention und Therapie fur Tater und Opfer von Schulbullying: Ein systematisches Review. Prax. Der Kinderpsychol. Und Kinderpsychiatr. 2017, 66, 740–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-García, D.; García, T.; Núñez, J.C. Predictors of school bullying perpetration in adolescence: A systematic review. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2015, 23, 126–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kljakovic, M.; Hunt, C. A meta-analysis of predictors of bullying and victimisation in adolescence. J. Adolesc. 2016, 49, 134–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Cleave, J.; Davis, M.M. Bullying and peer victimization among children with special health care needs. Pediatrics 2006, 118, e1212–e1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turcotte Benedict, F.; Vivier, P.M.; Gjelsvik, A. Mental health and bullying in the United States among children aged 6 to 17 years. J. Interpers. Violence 2015, 30, 782–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumpulainen, K. Psychiatric conditions associated with bullying. Int. J. Adolesc. Med. Health 2008, 20, 121–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterzing, P.R.; Shattuck, P.T.; Narendorf, S.C.; Wagner, M.; Cooper, B.P. Bullying involvement and autism spectrum disorders: Prevalence and correlates of bullying involvement among adolescents with an autism spectrum disorder. Arch. Pediatrics Adolesc. Med. 2012, 166, 1058–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, Y.-m.; Song, M.; Kim, S. An integrative review of intervention for school-bullying perpetrators. J. Korean Acad. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2018, 27, 355–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Academic, C.f. CASEL Guide: Effective Social and Emotional Learning Programs—Preschool and Elementary School Edition; Collaborative for Academic. Social, and Emotional Learning: Chicago, IL, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Portnow, S.; Downer, J.T.; Brown, J. Reductions in aggressive behavior within the context of a universal, social emotional learning program: Classroom-and student-level mechanisms. J. Sch. Psychol. 2018, 68, 38–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knowler, C.; Frederickson, N. Effects of an emotional literacy intervention for students identified with bullying behaviour. Educ. Psychol. 2013, 33, 862–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Buchner, A.; Erdfelder, E.; Faul, F.; Lang, A. G* Power 3.1 Manual; Heinrich-Heine-Universitat Dusseldorf: Düsseldorf, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- You, W.Y. The Effect of A Group Program on Self-Efficacy, Anger Adjustment, Empathy of School Bullying Students. Doctoral Dissertation, Deagu University, Deagu, Korea, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Seels, B.B.; Richey, R.C. Instructional Technology: The Definition and Domains of the Field; Association for Educational Communications and Techonology: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, J.J.-C. Investigating Adverse Effects of Adolescent Group Interventions; Arizona State University: Tempe, AZ, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kwon, Y.-U. Effects of Social and Emotional Learning Program on Social and Emotional Outcomes and School Adjustment. Doctoral Dissertation, Gyeongsang National University, Jinju, Korea, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Gueldner, B.A.; Feuerborn, L.L.; Merrell, K.W. Social and Emotional Learning in the Classroom: Promoting Mental Health and Academic Success; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmivalli, C. Participant role approach to school bullying: Implications for interventions. J. Adolesc. 1999, 22, 453–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, M. Participation in bullying: Bystanders’ characteristics and role behaviors. Korean J. Child Stud. 2008, 29, 79–96. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach, T.M. Integrative Guide for the 1991 CBCL/4-18, YSR, and TRF Profiles; Department of Psychiatry, University of Vermont: Burlington, VT, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Oh, K.; Kim, Y.; Ha, E.; Lee, H.; Hong, K. Korean Version of Youth Self Report; Huno Consulting Inc.: Seoul, Korea, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Shek, D.T.; Ma, C. Longitudinal data analyses using linear mixed models in SPSS: Concepts, procedures and illustrations. Sci. World J. 2011, 11, 42–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Şahin, M. An investigation into the efficiency of empathy training program on preventing bullying in primary schools. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2012, 34, 1325–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, B.H.; Low, S. The role of social-emotional learning in bullying prevention efforts. Theory Into Pract. 2013, 52, 280–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Session | Theme | Objectives | Contents |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1st † | Orientation | a. Increasing overall understanding of the program and SEC b. Forming rapport through individual interview | a. Introducing program objectives and process b. Assessing school bullying experience and mental health status c. Understanding the meaning and importance of SEC d. Setting program rules and establishing contract |

| 2nd | Self-awareness | a. Understanding oneself-needs, values, strengths-through exploring and exposure b. Identify and express emotion | a. Knowing one’s needs and values b. Recognizing strengths in, and mobilizing positive feelings about self, school, family, and support networks c. Recognizing and naming one’s emotions using emotion words d. Understanding the reasons and circumstances for feeling as one does |

| 3rd | Self-management (I) Emotional regulation | a. Understanding the cognitive triangle b. Application of the emotion regulation techniques to daily life | a. Verbalizing and coping with anxiety, depression, and anger b. Understanding the links between thought, emotion, and behavior c. Identify the ‘think trap’ and replace negative thoughts with positive alternatives d. Discuss how to regulate emotions |

| 4th | Self-management (II) Stress management | a. Managing personal and interpersonal stress b. Establishing a coping strategy | a. Understanding the concepts and influence of stress b. Identifying one’s stress, stressor, stressful events, and levels c. Identifying the physical and mental signs of a stress situation d. Finding Healthy and useful coping strategies using a “Stress recipe” |

| 5th | Social awareness (I) Understanding Empathy | a. Understanding diversity and others’ perspectives b. Recognizing others’ emotions c. Increasing empathy | a. Understanding others’ perspectives, points of view, and feelings b. Showing sensitivity to social–emotional cues using a “Ekman’s facial expression” and “Cartoons” c. Thinking from the other side’s perspective d. Understanding victim’s mind in school violence situation |

| 6th | Social awareness (II) Practicing Empathy | a. Increasing listening closely b. Increasing empathic expression | a. Increasing empathy and sensitivity to others’ feelings b. Identifying language expressing empathy c. Practice active empathic listening d. Practice empathic communication skills |

| 7th | Relation skills | a. Enhancing conflict solving skills b. Enhancing communication skills | a. Understanding social conflict and the cause b. Explore conflict resolution c. Identify frequently used languages and exchange negative expressions d. Practice “I-message” e. Developing assertiveness |

| 8th | Responsible decision making (I) Decision making | a. Understanding the importance of decision b. Making reasonable decisions | a. Sharing and discussing our decision recently b. Considering the impact of decision using the “Butterfly effect” c. Reconsidering the regretting decision according to the decision-making process d. Strategy for better decision making |

| 9th | Responsible decision making (II) Goal-setting | a. Setting realistic short- and long-term goals b. Improving responsibility for life by exposing goals | a. Understanding SMART goals: Specific, Measurable, Attainable, Relevant, and Timely b. Setting and sharing goals using a “Roadmap for life” c. Discuss strategies for achieving goals |

| 10th † | Reflection & wrap-up | a. Reflect their own changes through individual interview b. Find social support | a. Review SEC enhancement strategies b. Identify one’s change during the program c. Share specific plans to apply the learned interventions in daily life after the end of program d. Find social support to help keep changes e. Evaluating changes |

| Characteristic | Category | Total (n = 71) n (%) or Mean ± SD | Exp. (n = 35) n (%) or Mean ± SD | Cont. (n = 36) n (%) or Mean ± SD | t or χ2 | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 14.41 ± 0.82 | 14.46 ± 0.85 | 14.36 ± 0.80 | 0.49 | 0.626 | |

| Gender | Boy | 65 (91.5) | 33 (94.3) | 32 (88.9) | 0.67 † | 0.674 |

| Girl | 6 (8.5) | 2 (5.7) | 4 (11.1) | |||

| Friendship | Bad | 0 (0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.00 | 0.949 |

| Moderate | 16 (22.5) | 8 (22.9) | 8 (22.2) | |||

| Good | 55 (77.5) | 27 (77.1) | 28 (77.8) | |||

| Academic performance | Low | 26 (36.6) | 14 (40.0) | 12 (33.3) | 2.47 | 0.290 |

| Middle | 27 (38.0) | 15 (42.9) | 12 (33.3) | |||

| High | 18 (25.4) | 6 (17.1) | 12 (33.3) | |||

| SES | Low | 5 (7.0) | 3 (8.6) | 2 (5.6) | 1.44 † | 0.486 |

| Middle | 62 (87.3) | 29 (82.9) | 33 (91.7) | |||

| High | 4 (5.6) | 3 (8.6) | 1 (2.8) | |||

| Dependent Variables | Total (n = 71) Mean ± SD | Exp. (n = 35) Mean ± SD | Cont. (n = 36) Mean ± SD | Z | p | |

| Social and emotional competence | Total | 139.38 ± 27.82 | 133.43 ± 24.71 | 145.17 ± 9.74 | −1.84 | 0.066 |

| Social Competence | 58.23 ± 12.35 | 55.69 ± 11.25 | 60.69 ± 13.01 | −1.73 | 0.084 | |

| Emotional Regulation | 29.97 ± 7.14 | 28.66 ± 6.24 | 31.25 ± 7.79 | −1.45 | 0.147 | |

| Empathy | 18.52 ± 4.09 | 17.71 ± 4.03 | 19.31 ± 4.04 | −1.70 | 0.089 | |

| Self-esteem | 32.66 ± 6.80 | 32.66 ± 6.80 | 33.92 ± 7.50 | −1.64 | 0.102 | |

| School bullying behavior | 8.68 ± 5.82 | 9.91 ± 5.89 | 7.47 ± 5.57 | −1.87 | 0.062 | |

| Mental health | Total | 45.08 ± 9.43 | 46.94 ± 9.16 | 43.28 ± 9.47 | −1.81 | 0.070 |

| Internalizing | 42.63 ± 9.38 | 43.97 ± 9.55 | 41.33 ± 9.17 | −1.20 | 0.263 | |

| Externalizing | 50.13 ± 11.46 | 51.51 ± 9.57 | 48.78 ± 13.03 | −0.97 | 0.319 |

| Outcomes | Category | Time | Exp. (n = 35) | Cont. (n = 36) | Time | Group | Group × Time | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M ± SD | M ± SD | F or Wald χ2 | p | F or Wald χ | p | F or Wald χ | p | |||

| Social and emotional competence | Total | Pre | 133.43 ± 24.71 | 145.17 ± 29.74 | 11.84 | 0.001 | 6.07 | 0.016 | 6.42 | 0.013 |

| Post I | 147.40 ± 30.98 | 152.03 ± 33.20 | ||||||||

| Post II | 150.09 ± 35.22 | 146.12 ± 33.81 | ||||||||

| Social Competence | Pre | 55.69 ± 11.25 | 60.69 ± 13.01 | 5.88 | 0.017 | 5.24 | 0.024 | 5.18 | 0.025 | |

| Post I | 61.00 ± 13.25 | 63.56 ± 14.58 | ||||||||

| Post II | 61.94 ± 14.55 | 60.42 ± 14.17 | ||||||||

| Emotional Regulation | Pre | 28.66 ± 6.24 | 31.25 ± 7.79 | 19.25 | <0.001 | 5.06 | 0.027 | 6.01 | 0.016 | |

| Post I | 31.57 ± 8.09 | 33.11 ± 8.23 | ||||||||

| Post II | 33.71 ± 8.96 | 32.15 ± 8.20 | ||||||||

| Empathy | Pre | 17.71 ± 4.03 | 19.31 ± 4.04 | 5.95 | 0.017 | 3.99 | 0.049 | 4.79 | 0.031 | |

| Post I | 19.86 ± 4.59 | 19.81 ± 4.71 | ||||||||

| Post II | 19.74 ± 5.47 | 19.39 ± 5.10 | ||||||||

| Self-esteem | Pre | 31.37 ± 5.83 | 33.92 ± 7.50 | 6.44 | 0.013 | 4.11 | 0.046 | 3.45 | 0.066 | |

| Post I | 34.34 ± 7.58 | 35.56 ± 7.52 | ||||||||

| Post II | 34.71 ± 8.04 | 34.15 ± 8.46 | ||||||||

| School bullying behavior | Pre | 9.91 ± 5.89 | 7.47 ± 5.57 | 93.29 | <0.001 | 0.06 | 0.804 | 20.19 | <0.001 | |

| Post I | 7.43 ± 5.56 | 6.28 ± 5.40 | ||||||||

| Post II | 2.74 ± 3.70 | 5.48 ± 5.91 | ||||||||

| Mental health | Total | Pre | 46.94 ± 9.16 | 43.28 ± 9.47 | 11.45 | 0.001 | 3.12 | 0.081 | 0.30 | 0.583 |

| Post I | 44.29 ± 12.00 | 39.28 ± 10.79 | ||||||||

| Post II | 41.25 ± 10.64 | 41.86 ± 14.08 | ||||||||

| Internalizing | Pre | 43.97 ± 9.55 | 41.33 ± 9.17 | 5.08 | 0.027 | 3.16 | 0.079 | 1.83 | 0.179 | |

| Post I | 41.17 ± 9.35 | 39.06 ± 8.56 | ||||||||

| Post II | 39.33 ± 11.37 | 40.93 ± 15.55 | ||||||||

| Externalizing | Pre | 51.51 ± 9.57 | 48.78 ± 13.03 | 7.83 | 0.007 | 1.11 | 0.295 | 0.13 | 0.909 | |

| Post I | 49.54 ± 13.76 | 44.86 ± 14.44 | ||||||||

| Post II | 46.67 ± 11.37 | 42.90 ± 13.44 | ||||||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Song, Y.-m.; Kim, S. Effects of a Social and Emotional Competence Enhancement Program for Adolescents Who Bully: A Quasi-Experimental Design. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 7339. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19127339

Song Y-m, Kim S. Effects of a Social and Emotional Competence Enhancement Program for Adolescents Who Bully: A Quasi-Experimental Design. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(12):7339. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19127339

Chicago/Turabian StyleSong, Yul-mai, and Sunah Kim. 2022. "Effects of a Social and Emotional Competence Enhancement Program for Adolescents Who Bully: A Quasi-Experimental Design" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 12: 7339. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19127339