Emotional Intelligence as a Predictor of Motivation, Anxiety and Leadership in Athletes

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Method

2.2. Participants

2.3. Instruments

- The TMMS-24 [23] corresponds to a kind of submodel of emotional intelligence created from the model of [6], which some authors call the Spanish version of the model of [6]. For these authors, emotional intelligence is composed of three dimensions, such as the perception, understanding and regulation of emotions through a Likert-type scale [24]. A Cronbach’s alpha = 0.84 was obtained in this study. It is composed of twenty-four items, eight of which refer to one’s own feelings, eight to clarity and eight to the regulation of feelings, resulting in a Likert-type scale of self-knowledge that assesses three dimensions of emotional intelligence: attention to feelings, emotional clarity and emotion repair.

- The adaptation of the Sport Leadership Behavior Inventory was developed by [26]. This scale measures aspects of leadership related to social support, empathy, sport values, and influence in decision making and task orientation through a Likert-type scale. A Cronbach’s alpha = 0.94 was obtained in this study, whereas a Cronbach’s alpha score of 0.84 was obtained in other studies [27].

- The sport motivational mediators scale [28] measures the beliefs and mediators that predict motivation through a Likert-type scale. A Cronbach’s alpha = 0.71 was obtained for this work. The reliability of the original instrument is 0.75 for the first factor; 0.76 for the second; and 0.71 for the third [29].

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

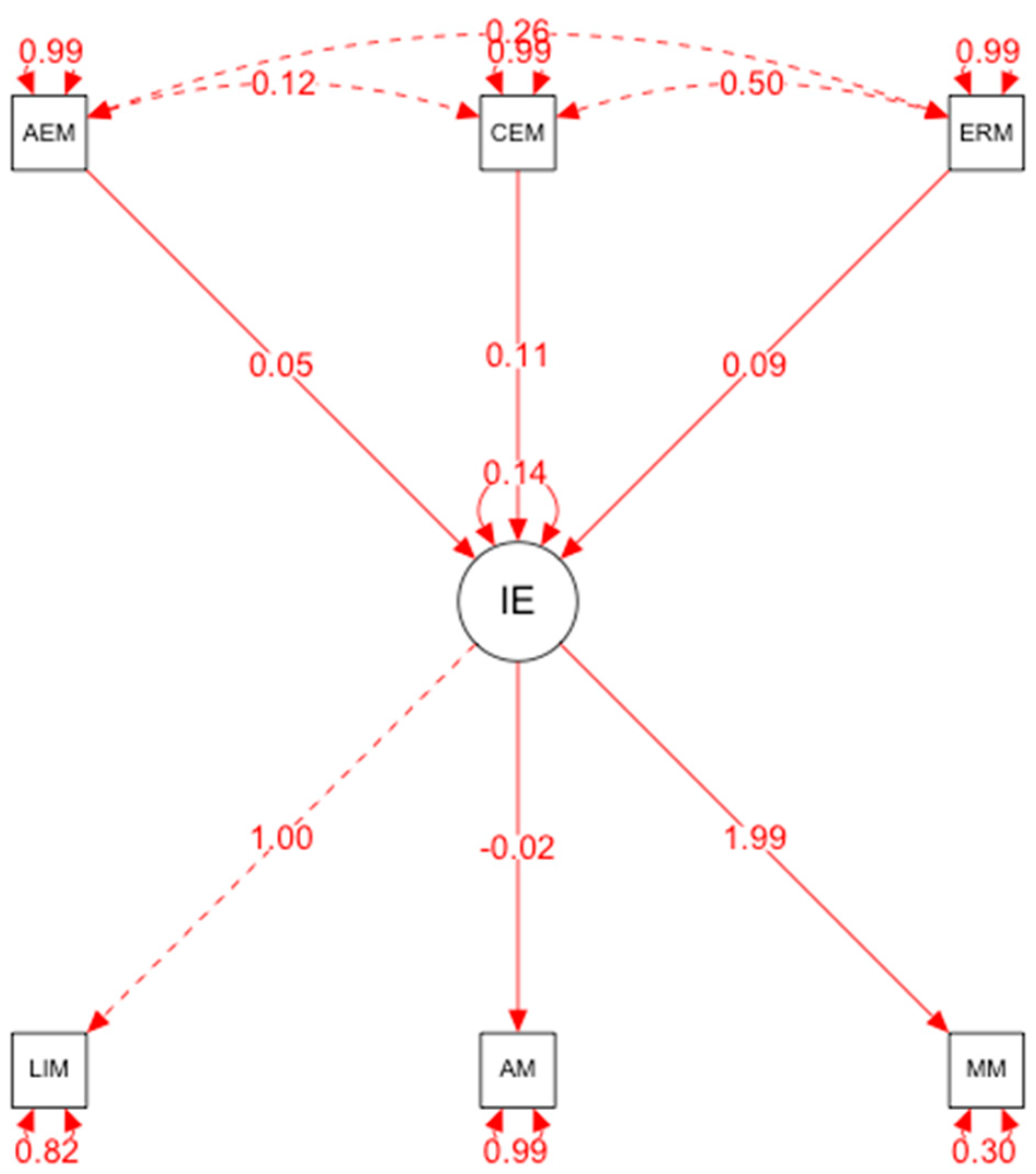

Structural Equation Mode

- (a)

- Emotional intelligence and motivation were positively correlated (β = 0.30, p < 0.001). This explains that, in this case, emotional intelligence is a predictor of motivation; therefore, the presence of this variable explains the existence of the other variable.

- (b)

- Emotional intelligence and anxiety were positively related (β = 0.02, p < 0.001). These results show that emotional intelligence also predicts the occurrence of anxiety in an explanatory manner.

- (c)

- Emotional intelligence and leadership were not positively related. However, the results do not establish that emotional intelligence is a predictor variable of leadership; therefore, the presence of emotional intelligence does not correspond with the appearance of high levels of leadership.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mitić, P.; Nedeljković, J.; Bojanić, Ž.; Franceško, M.; Milovanović, I.; Bianco, A.; Drid, P. Differences in the psychological profiles of elite and non-elite athletes. Front. Psychol. 2020, 12, 769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cowden, R.G. Mental toughness, emotional intelli gence, and coping effectiveness: An analysis of construct interrelatedness among high-performing adolescent male athletes. Percept. Mot. Skill 2020, 123, 737–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y.H.; Chelladurai, P. Emotional intelligence, emotional labor, coach burnout, job satisfaction, and turnover intention in sport leadership. Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 2018, 18, 393–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orangi, B.M.; Lenoir, M.; Yaali, R.; Ghorbanzadeh, B.; O’Brien-Smith, J.; Galle, J.; De Meester, A. Emotional intelligence and motor competence in children, adolescents, and young adults. Eur. J. Dev. Psychol. 2020, 1, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, P.; Lacerda, A.; Melo, R.; Habib, L.R.; Filgueiras, A. Psicoeducação baseada em evidências no esporte: Revisão bibliográfica e proposta de intervenção para mane jo emocional. Rev. Bras. Psicol. Esporte 2018, 8, 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, J.D.; Salovey, P. What is emotional intelligence? In Emotional Development and Emotional Intelligence: Implications for Educators; Salovey, P., Sluyter, D., Eds.; Basic Books: New, York, NY, USA, 1997; pp. 3–31. [Google Scholar]

- Lott, G.H.; Turner, B.A. Collegiate Sport Participation and Student-Athlete Development through the Lens of Emotional Intelligence. J. Amat. Sport 2018, 4, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaughan, R.; Laborde, S. Psychometrics of the emotional intelligence scale in elite, amateur, and non-athletes. Meas. Phys. Educ. Exerc. Sci. 2017, 22, 177–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerber, M.; Best, S.; Meerstetter, F.; Walter, M.; Ludyga, S.; Brand, S.; Bianchi, R.; Madigan, D.J.; Isoard-Gautheur, S.; Gustafsson, H. Effects of stress and mental toughness on burnout and depressive symptoms: A prospective study with young elite athletes. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2018, 21, 1200–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Zafra, M.; Cachon-Zagalaz, J.; Zabala-Sánchez, M.L. Emotional intelligence, self-concept and physical activity practice in university students. J. Sport Health Res. 2022, 14, 135–148. [Google Scholar]

- Castro-Sánchez, M.; Zurita-Ortega, F.; Chacón-Cuberos, R.; López-Gutiérrez, C.J.; Zafra-Santos, E. Emotional intelligence, motivational climate and levels of anxiety in athletes from different categories of sports: Analysis through structural equations. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Castro-Sánchez, M.; Lara-Sánchez, A.J.; Zurita-Ortega, F.; Chacón-Cuberos, R. Motivation, anxiety, and emotional intelligence are associated with the practice of contact and non-contact sports: An explanatory model. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gallegos, A.G.; López, M.G. La motivación y la inteligencia emocional en secundaria. Diferencias por género. Int. J. Dev. Educ. Psychol. 2020, 1, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Méndez-Giménez, A.; del Pilar Mahedero-Navarrete, M.; Puente-Maxera, F.; de Ojeda, D.M. Effects of the Sport Education model on adolescents’ motivational, emotional, and well-being dimensions during a school year. Eur. Phys. Educ. Rev. 2021, 28, 380–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotterill, S.T.; Fransen, K. Leadership in team sports: Current understanding and future directions. Int. Rev. Sport Exerc. Psychol 2015, 9, 116–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Northouse, P.G. Leadership: Theory and Practice, 8th ed.; Sage: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Cotterill, S.T.; Loughead, T.M.; Fransen, K. Athlete Leadership Development Within Teams: Current Understanding and Future Directions. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 820745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leo, F.M.; García-Calvo, T.; González-Ponce, I.; Pulido, J.J.; Fransen, K. How many leaders does it take to lead a sports team? The relationship between the number of leaders and the effectiveness of professional sports teams. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0218167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Berrocal, P.; Extremera, N.; Ramos, N. Validity and reliability of the Spanish modified version of the Trait Meta-Mood Scale. Psychol. Rep. 2004, 94, 751–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Extremera, N.; Fernández, P. ¿Es la inteligencia emocional un adecuado predictor del rendimiento académico en estudiantes? In III Jornadas de Innovación Pedagógica: Inteligencia Emocional. Una Brújula Para el Siglo XXI; Emotional Intelligence: A Compass for the 21st Century: Granada, Spain, 2001; pp. 146–157. [Google Scholar]

- Arce, C.; Torrado, J.; Andrade, E.; Alzate, M. Evaluación del liderazgo informal en equipos deportivos. Rev. Latinoam. De Psicol. 2011, 43, 157–165. [Google Scholar]

- González-Cutre, D.; Martínez, C.; Alonso, N.; Cervelló, E.; Conte, L.; Moreno, J.A. Las creencias implícitas de habilidad y los mediadores psicológicos como variables predictoras de la motivación autodeterminada en deportistas adolescentes. In Investigación en la Actividad Física y el Deporte II; Castellano, J., y Usabiaga, O., Eds.; Universidad del País Vasco: Victoria, Australia, 2007; pp. 407–417. [Google Scholar]

- Martens, R. Sport Competition Anxiety Test; Human Kinetics: Champaign, IL, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Jöreskog, K.G. A general method for analysis of covariance structures. Biometrika 1970, 57, 239–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jöreskog, K.G. Identification and estimation in path analysis with unmeasured variables. Am. J. Sociol. 1973, 78, 1469–1484. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L.T.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Modeling A Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luna, P.; Guerrero, J.; Cejudo, J. Improving adolescents’ subjective well-being, trait emotional intelligence and social anxiety through a programme based on the sport education model. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sánchez, J.A.; Peinado, M.G.; Giráldez, C.M. Relación entre inteligencia emocional y ansiedad en un club de fútbol sala de Madrid (Relationship between emotional intelligence and anxiety in a futsal club from Madrid). Retos 2021, 39, 643–648. [Google Scholar]

- Tinkler, N.; Kruger, A.; Jooste, J. Relationship between emotional intelligence and components of competitive state anxiety among south african female field-hockey players. S. Afr. J. Res. Sport Phys. Educ. Recreat. 2021, 43, 87–100. [Google Scholar]

- Torrado Quintela, J.; Arce Fernández, C. Liderazgo Entre Iguales en Equipos Deportivos: Elaboración de un Instrumento de Medida; Universitat de Les Illes Balears: Palma, Spain, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, T.I.; Wang, M.Y.; Huang, B.R.; Hsu, C.Y.; Chien, C.Y. Effects of Psychological Capital and Sport Anxiety on Sport Performance in Collegiate Judo Athletes. Am. J. Health Behav. 2022, 46, 197–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angulo, R.; Albarracín, A.P. Validez y confiabilidad de la escala rasgo de metaconocimiento emocional (TMMS-24) en profesores universitarios. Rev. Lebret 2018, 10, 61–72. [Google Scholar]

- Gabilondo, J.A.; Rodríguez, O.G.; Moreno, M.P.; Galarraga, S.A.; Estrada, J.C. Validación del competitive state anxiety inventory 2 reducido (csai-2 re) mediante una aplicación web. Int. J. Med. Sci. Phys. Act. Sport 2012, 12, 539–556. [Google Scholar]

- Soper, D.S. A-priori Sample Size Calculator for Structural Equation Models [Software]. 2022. Available online: https://www.danielsoper.com/statcalc (accessed on 1 January 2020).

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Emotional attention (AE) | ||||||

| 2. Emotional clarity (CE) | 0.127 | 0.263 ** | 0.150 | 0.321 ** | 0.181 * | |

| 3. Emotional regulation (ERM) | 0.508 ** | 0.156 * | −0.069 | 0.321 ** | ||

| 4. Leadership (LIM) | 0.157 * | −0.052 | 0.326 ** | |||

| 5. Anxiety (AM) | 0.049 | 0.364 ** | ||||

| 6. Motivation (MM) | −0.018 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rubio, I.M.; Ángel, N.G.; Esteban, M.D.P.; Ruiz, N.F.O. Emotional Intelligence as a Predictor of Motivation, Anxiety and Leadership in Athletes. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 7521. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19127521

Rubio IM, Ángel NG, Esteban MDP, Ruiz NFO. Emotional Intelligence as a Predictor of Motivation, Anxiety and Leadership in Athletes. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(12):7521. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19127521

Chicago/Turabian StyleRubio, Isabel Mercader, Nieves Gutiérrez Ángel, María Dolores Pérez Esteban, and Nieves Fátima Oropesa Ruiz. 2022. "Emotional Intelligence as a Predictor of Motivation, Anxiety and Leadership in Athletes" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 12: 7521. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19127521

APA StyleRubio, I. M., Ángel, N. G., Esteban, M. D. P., & Ruiz, N. F. O. (2022). Emotional Intelligence as a Predictor of Motivation, Anxiety and Leadership in Athletes. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(12), 7521. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19127521