Effects of COVID-19 on Adolescent Mental Health and Internet Use by Ethnicity and Gender: A Mixed-Method Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

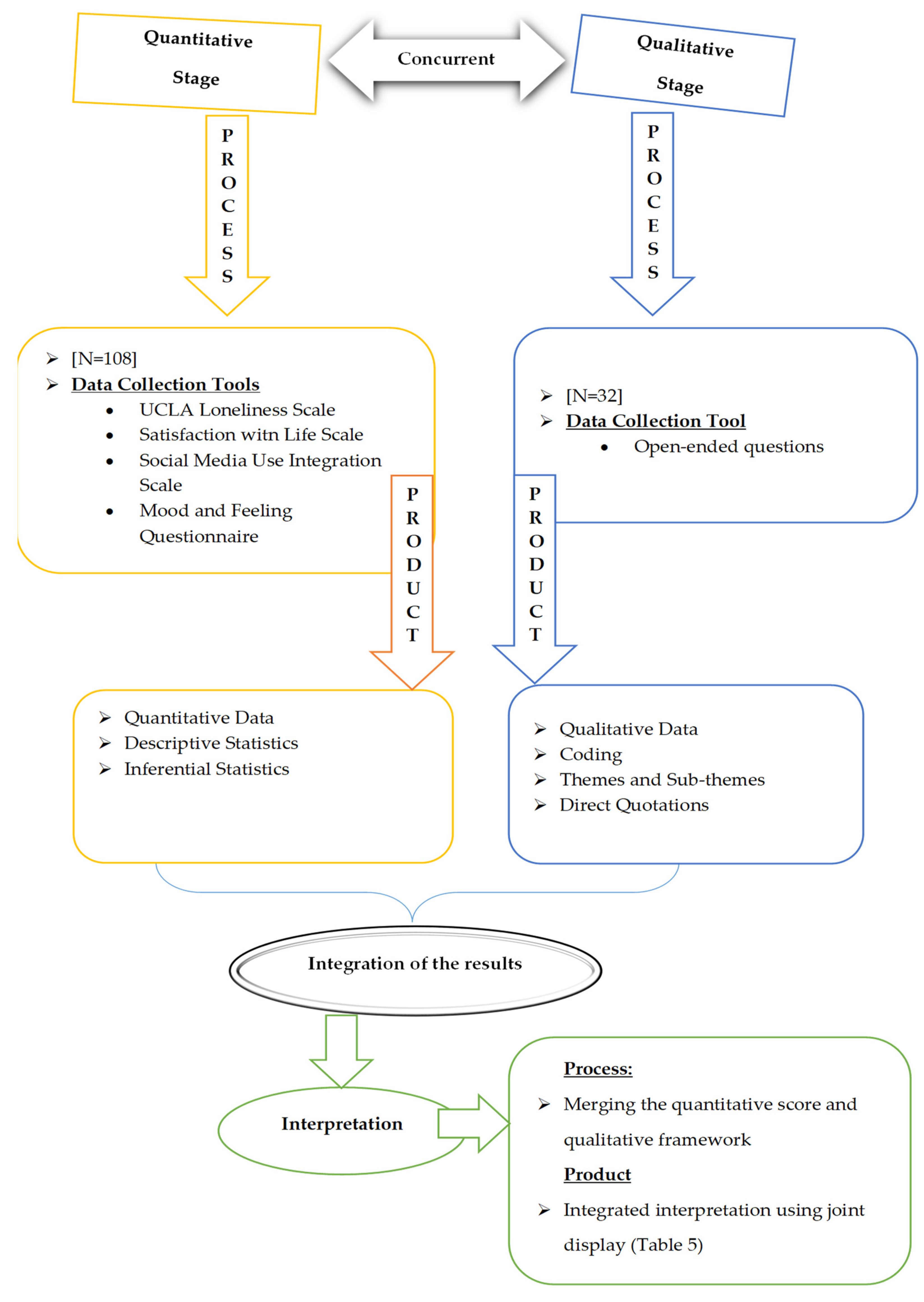

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Questionnaires

2.3. Quantitative Analysis

2.4. Qualitative Analysis

2.5. Trustworthiness

3. Results

3.1. Quantitative Results

3.2. Qualitative Results

- (1)

- The effect of internet use on mental health during COVID-19;

- (2)

- Mood and life satisfaction before COVID-19;

- (3)

- Mood and life satisfaction during COVID-19.

- (1)

- The effect of internet use on mental health during COVID-19

“I actually think the internet has improved my mood. My friend created a new group chat on Instagram, I have enjoyed talking with everyone. I believe that without this chat I would have found it difficult to reach out to people and would’ve begun to isolate myself. It has stopped me from feeling lonely. Furthermore, the internet has provided me with good entertainment to make my lockdown better. The only negative that the internet has brought is the constant stream of upsetting news stories, I found myself having to ignore information such as COVID-19 statistics to prevent my anxiety.”(13WHITE-LD-F)

“I have used the internet more than usual and it has in some aspects positively affected my mood. I have made more online friends with whom I communicate with regularly and share my schoolwork and social life with. For leisure, I have also, used my play-station to play online games with other friends. I have used the internet significantly more for both educational and social purposes. Educationally, I have used the internet to research topics relating to COVID-19 as well as mental health issues related to the elderly during the pandemic. This has helped me to better understand and take care of my grandmother. Socially, I have interacted with other people with who I would otherwise have not shared my views.”(51BAME-LD-M)

“I’ve used the internet a lot more, for communication and entertainment purposes. I also seek mental health advice online when I can, and regularly check the status of COVID-19 to ease my concerns, such as what the government has said, the rates of it, scientific advice etc.”(18BAME-HD-F)

- (2)

- Mood and Life Satisfaction Before COVID-19

“My mood before the lockdown was much brighter and happier but I was a bit more stressed with school. Now my mood is less bright more drowsy and fatigued but less stressed. That’s all.”(2BAME-LD-F)

“I felt more peaceful and calm because not going to school decreased my social anxiety since I could stay home.”(69White-HD-M)

“Due to not having to be at school, my fear and stress have decreased a lot.”(72White-HD-F)

“Before lockdown, my mood was low often and my life satisfaction was low also. Due to school and exams, I had no free time nor did I have time to think about my mental health as all my focus was on achieving good grades and getting homework done.”(18BAME-HD-F)

“My mood before lockdown was much better. I think having a daily routine and a plan helped me a lot but since lockdown, it’s thrown me. Being able to spend time face to face with my friends even at school was something that I really enjoyed. I think my satisfaction has gone down a little but is maintained from me being active and taking part in a variety of activities.”(48BAME-LD-F)

- (3)

- Mood and Life Satisfaction During COVID-19

“Initially the start of lockdown was not great, I felt rundown by the building pressures at school prior to lockdown and suddenly being isolated from others brought on a lot of stress.”(37BAME-LD-F)

“…the monotony of lockdown, it’s such a contrast from my usual daily life that it’s almost confusing to me. It has made my mood weirdly stable, and my range of emotions seems more limited than before. Each day seems to have merged into each other. I can’t pinpoint anything that has given me an overwhelmingly "good" or "bad" mood. There has been a couple of times where I have been upset about the uncertainty of the future and feeling that I’m wasting my time.”(13White-LD-F)

“Although my mood is ‘good’ I have found that my life satisfaction has decreased. I look back on the last few months and I can’t think of any memorable events or times where I had a great day. It almost feels like lost time, like I’ve been stuck in an airport since March.”(13White-LD-F)

“I think that my family have affected my mood the most in a bad way. I think I am generally grumpier and more fed up and I snap a lot due to being around only them. But on the other hand, I think talking to my friends has affected my mood in the best way, as I don’t often have long conversations with my friends, recently I have had more and have enjoyed them.”(32BAME-HD-F)

“I felt more awake and relaxed, as I didn’t have major exams to stress about anymore. I am getting the right amount of sleep for myself, and I was able to pursue my hobby of making bracelets. It did get a little stressful as I found it harder to do schoolwork at home. Overall, I was happier during lockdown than before lockdown.”(76White-LD-F)

“Due to how much school negatively affected me, my mood initially spiked and I have felt happier and more in control since. However, the worry of going out and worrying about vulnerable family members, not being able to see people and the isolation has negatively affected how I feel, particularly about myself. However, overall, the break to my normally busy life has done better than anything.”(72White-HD-F)

3.3. Merged Analysis Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Codes/Categories | Gender | Depression Level | Ethnicity | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | HD | LD | White | BAME | |

| Negative | 4% | 14% | 11% | 8% | 11% | 7% |

| Comparing self to others | 1% | 4% | 3% | 3% | 4% | 1% |

| Escapism | 0% | 4% | 2% | 3% | 2% | 3% |

| Racism | 2% | 1% | 3% | 1% | 1% | 2% |

| Sad news | 1% | 4% | 4% | 2% | 4% | 1% |

| Positive | 41% | 41% | 46% | 36% | 36% | 46% |

| Beatific | 3% | 3% | 4% | 2% | 1% | 5% |

| Become socialised | 4% | 3% | 4% | 4% | 3% | 4% |

| Coping strategies-Ease Concern | 4% | 4% | 6% | 3% | 3% | 6% |

| Distance education | 3% | 4% | 2% | 6% | 4% | 4% |

| Enjoyable-Entertainment | 6% | 4% | 6% | 4% | 4% | 6% |

| Grounding | 7% | 10% | 10% | 7% | 8% | 8% |

| Mental health advice | 2% | 3% | 2% | 3% | 1% | 4% |

| Social Media | 4% | 4% | 6% | 3% | 4% | 4% |

| Staying connected | 7% | 4% | 6% | 5% | 7% | 4% |

| Total | 45% | 55% | 57% | 54% | 47% | 53% |

Appendix B

| Codes/Categories | Gender | Depression Level | Ethnicity | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | HD | LD | White | BAME | |

| A-Before lockdown | ||||||

| A1-Negative Aspects of Life | 38% | 31% | 41% | 28% | 38% | 31% |

| Less awareness | 5% | 0% | 5% | 0% | 5% | 0% |

| Low mood | 0% | 5% | 3% | 3% | 3% | 3% |

| No free time | 3% | 3% | 3% | 3% | 0% | 5% |

| School anxiety- School worse than COVID | 31% | 23% | 31% | 23% | 31% | 23% |

| A2-Positive Aspects of Life | 15% | 15% | 18% | 13% | 13% | 18% |

| Better | 5% | 5% | 3% | 8% | 3% | 8% |

| Freedom | 5% | 3% | 5% | 3% | 3% | 5% |

| Happy-satisfied | 5% | 8% | 10% | 3% | 8% | 5% |

| Total | 53% | 46% | 59% | 41% | 51% | 49% |

| B-During lockdown | ||||||

| B1-Negative Aspects of Life | 36% | 30% | 37% | 29% | 32% | 34% |

| Anger-Trapped | 3% | 1% | 2% | 2% | 3% | 1% |

| Anhedonia | 1% | 2% | 1% | 2% | 2% | 1% |

| Anxious-COVID fear | 2% | 4% | 5% | 1% | 4% | 2% |

| Feeling Depressed | 3% | 3% | 5% | 1% | 2% | 4% |

| Difficult to cope with | 0% | 2% | 1% | 1% | 1% | 1% |

| Family problems | 3% | 3% | 2% | 4% | 2% | 4% |

| Lack of motivation-Bored-Unproductive | 5% | 3% | 4% | 4% | 4% | 4% |

| Loneliness | 3% | 2% | 3% | 2% | 2% | 4% |

| Mood fluctuations | 3% | 2% | 2% | 3% | 3% | 2% |

| Restricted-isolated | 7% | 5% | 7% | 5% | 5% | 7% |

| Sad | 1% | 3% | 2% | 2% | 2% | 2% |

| Stressed | 2% | 2% | 2% | 2% | 2% | 2% |

| Worse | 3% | 2% | 3% | 2% | 3% | 2% |

| B2-Positive Aspects of Life | 11% | 23% | 14% | 20% | 16% | 18% |

| Developing a hobby | 2% | 4% | 1% | 4% | 2% | 4% |

| Feeling better | 2% | 6% | 3% | 5% | 4% | 4% |

| Happy | 3% | 4% | 2% | 4% | 4% | 3% |

| Increasing awareness | 2% | 3% | 3% | 2% | 3% | 2% |

| Less pressure-Relaxation | 1% | 3% | 2% | 3% | 2% | 2% |

| New friends | 1% | 1% | 1% | 0% | 0% | 1% |

| Re-evaluating priorities | 1% | 3% | 2% | 2% | 1% | 3% |

| Spending time with family | 1% | 1% | 0% | 2% | 2% | 0% |

| Total | 47% | 53% | 51% | 49% | 48% | 52% |

References

- Betsch, C. How behavioural science data helps mitigate the COVID-19 crisis. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2020, 4, 438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- GOV.UK. Prime Minister’s Statement on Coronavirus (COVID-19): 16 March 2020. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/speeches/pm-statement-on-coronavirus-16-march-2020 (accessed on 24 December 2020).

- Mindel, C.; Salhi, L.; Oppong, C.; Lockwood, J. Alienated and unsafe: Experiences of the first national UK COVID-19 lockdown for vulnerable young people (aged 11–24 years) as revealed in Web-based therapeutic sessions with mental health professionals. Couns. Psychother. Res. 2022, 22, 708–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Kock, J.H.; Ann Latham, H.; Cowden, R.G.; Cullen, B.; Narzisi, K.; Jerdan, S.; Muñoz, S.-A.; Leslie, S.J.; McNamara, N.; Boggon, A.; et al. The mental health of NHS staff during the COVID-19 pandemic: Two-wave Scottish cohort study. BJPsych Open 2022, 8, e23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NHS. Research into Stress in Healthcare Workers during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Available online: https://www.hra.nhs.uk/planning-and-improving-research/application-summaries/research-summaries/research-into-stress-in-healthcare-workers-during-the-covid19-pandemic-covid-19/ (accessed on 26 May 2022).

- Bueno-Notivol, J.; Gracia-García, P.; Olaya, B.; Lasheras, I.; López-Antón, R.; Santabárbara, J. Prevalence of depression during the COVID-19 outbreak: A meta-analysis of community-based studies. Int. J. Clin. Health Psychol. 2021, 21, 100196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varma, P.; Junge, M.; Meaklim, H.; Jackson, M.L. Younger people are more vulnerable to stress, anxiety and depression during COVID-19 pandemic: A global cross-sectional survey. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2021, 109, 110236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Racine, N.; Cooke, J.E.; Eirich, R.; Korczak, D.J.; McArthur, B.; Madigan, S. Child and adolescent mental illness during COVID-19: A rapid review. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 292, 113307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terry, P.C.; Parsons-Smith, R.L.; Terry, V.R. Mood responses associated with COVID-19 restrictions. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 589598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vizard, T.; Sadler, K.; Ford, T.; Newlove-Delgado, T.; McManus, S.; Marcheselli, F.; Davis, J.; Williams, T.; Leach, C.; Mandalia, D. Mental health of children and young people in England, 2020. Change 2020, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Waite, P.; Pearcey, S.; Shum, A.; Raw, J.A.L.; Patalay, P.; Creswell, C. How did the mental health symptoms of children and adolescents change over early lockdown during the COVID-19 pandemic in the UK? J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry Adv. 2021, 1, e12009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapee, R.M.; Oar, E.L.; Johnco, C.J.; Forbes, M.K.; Fardouly, J.; Magson, N.R.; Richardson, C.E. Adolescent development and risk for the onset of social-emotional disorders: A review and conceptual model. Behav. Res. Ther. 2019, 123, 103501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waltereit, R.; Uhlmann, A.; Roessner, V. Adolescent psychiatry—From the viewpoint of a child and adolescent psychiatrist. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2018, 27, 1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Davies, S.C. Chief Medical Officer’s Introduction. In Annual Report of the Chief Medical Officer 2013, Public Mental Health Priorities: Investing in the Evidence; Mehta, N., Murphy, O., Lillford-Wildman, C., Eds.; Department of Health: London, UK, 2013; pp. 9–20. [Google Scholar]

- Colizzi, M.; Lasalvia, A.; Ruggeri, M. Prevention and early intervention in youth mental health: Is it time for a multidisciplinary and trans-diagnostic model for care? Int. J. Ment. Health Syst. 2020, 14, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bergin, A.D.; Vallejos, E.P.; Davies, E.B.; Daley, D.; Ford, T.; Harold, G.; Hetrick, S.; Kidner, M.; Long, Y.; Merry, S. Preventive digital mental health interventions for children and young people: A review of the design and reporting of research. NPJ Digit. Med. 2020, 3, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hollis, C.; Falconer, C.J.; Martin, J.L.; Whittington, C.; Stockton, S.; Glazebrook, C.; Davies, E.B. Annual research review: Digital health interventions for children and young people with mental health problems—A systematic and meta-review. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2017, 58, 474–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das-Munshi, J.; Stewart, R.; Morgan, C.; Nazroo, J.; Thornicroft, G.; Prince, M. Reviving the ‘double jeopardy’ hypothesis: Physical health inequalities, ethnicity and severe mental illness. Br. J. Psychiatry 2016, 209, 183–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ravi, K. Ethnic disparities in COVID-19 mortality: Are comorbidities to blame? Lancet 2020, 396, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proto, E.; Quintana-Domeque, C. COVID-19 and mental health deterioration by ethnicity and gender in the UK. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0244419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, K.; Bhui, K.; Cipriani, A. COVID-19, mental health and ethnic minorities. Evid. Based Ment. Health 2020, 23, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Droogenbroeck, F.; Spruyt, B.; Keppens, G. Gender differences in mental health problems among adolescents and the role of social support: Results from the Belgian health interview surveys 2008 and 2013. BMC Psychiatry 2018, 18, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Campbell, O.L.K.; Bann, D.; Patalay, P. The gender gap in adolescent mental health: A cross-national investigation of 566,829 adolescents across 73 countries. SSM-Popul. Health 2021, 13, 100742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fink, E.; Patalay, P.; Sharpe, H.; Holley, S.; Deighton, J.; Wolpert, M. Mental health difficulties in early adolescence: A comparison of two cross-sectional studies in England from 2009 to 2014. J. Adolesc. Health 2015, 56, 502–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, F.; Zheng, D.; Liu, J.; Gong, Y.; Guan, Z.; Lou, D. Depression and anxiety among adolescents during COVID-19: A cross-sectional study. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020, 88, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halldorsdottir, T.; Thorisdottir, I.E.; Meyers, C.C.A.; Asgeirsdottir, B.B.; Kristjansson, A.L.; Valdimarsdottir, H.B.; Allegrante, J.P.; Sigfusdottir, I.D. Adolescent well-being amid the COVID-19 pandemic: Are girls struggling more than boys? J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry Adv. 2021, 1, e12027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorisdottir, I.E.; Asgeirsdottir, B.B.; Kristjansson, A.L.; Valdimarsdottir, H.B.; Tolgyes, E.M.J.; Sigfusson, J.; Allegrante, J.P.; Sigfusdottir, I.D.; Halldorsdottir, T. Depressive symptoms, mental wellbeing, and substance use among adolescents before and during the COVID-19 pandemic in Iceland: A longitudinal, population-based study. Lancet Psychiatry 2021, 8, 663–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magson, N.R.; Freeman, J.Y.A.; Rapee, R.M.; Richardson, C.E.; Oar, E.L.; Fardouly, J. Risk and protective factors for prospective changes in adolescent mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Youth Adolesc. 2021, 50, 44–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kapetanovic, S.; Gurdal, S.; Ander, B.; Sorbring, E. Reported changes in adolescent psychosocial functioning during the COVID-19 outbreak. Adolescents 2021, 1, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grist, R.; Cliffe, B.; Denne, M.; Croker, A.; Stallard, P. An online survey of young adolescent girls’ use of the internet and smartphone apps for mental health support. BJPsych Open 2018, 4, 302–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lee, C.M.; Cadigan, J.M.; Rhew, I.C. Increases in loneliness among young adults during the COVID-19 pandemic and association with increases in mental health problems. J. Adolesc. Health 2020, 67, 714–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clair, R.; Gordon, M.; Kroon, M.; Reilly, C. The effects of social isolation on well-being and life satisfaction during pandemic. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2021, 8, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loades, M.E.; Chatburn, E.; Higson-Sweeney, N.; Reynolds, S.; Shafran, R.; Brigden, A.; Linney, C.; McManus, M.N.; Borwick, C.; Crawley, E. Rapid systematic review: The impact of social isolation and loneliness on the mental health of children and adolescents in the context of COVID-19. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2020, 59, 1218–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gigantesco, A.; Fagnani, C.; Toccaceli, V.; Stazi, M.A.; Lucidi, F.; Violani, C.; Picardi, A. The relationship between satisfaction with life and depression symptoms by gender. Front. Psychiatry 2019, 10, 419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Padmanabhanunni, A.; Pretorius, T. The loneliness-life satisfaction relationship: The parallel and serial mediating role of hopelessness, depression and ego-resilience among young adults in South Africa during COVID-19. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, S.-I.; Lim, X.-J.; Hsu, H.-C.; Chou, C.-C. Age-friendliness of city, loneliness and depression moderated by internet use during the COVID-19 pandemic. Health Promot. Int. 2022, daac040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossmann, C.; Meyer, L.; Schulz, P.J. The mediated amplification of a crisis: Communicating the A/H1N1 pandemic in press releases and press coverage in Europe. Risk Anal. 2018, 38, 357–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malecki, K.; Keating, J.A.; Safdar, N. Crisis communication and public perception of COVID-19 risk in the era of social media. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020, 72, 697–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cauberghe, V.; Van Wesenbeeck, I.; De Jans, S.; Hudders, L.; Ponnet, K. How adolescents use social media to cope with feelings of loneliness and anxiety during COVID-19 lockdown. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2021, 24, 250–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekalu, M.A.; McCloud, R.F.; Viswanath, K. Association of social media use with social well-being, positive mental health, and self-rated health: Disentangling routine use from emotional connection to use. Health Educ. Behav. 2019, 46, 69S–80S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hunt, M.G.; Marx, R.; Lipson, C.; Young, J. No more FOMO: Limiting social media decreases loneliness and depression. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 2018, 37, 751–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kross, E.; Verduyn, P.; Demiralp, E.; Park, J.; Lee, D.S.; Lin, N.; Shablack, H.; Jonides, J.; Ybarra, O. Facebook use predicts declines in subjective well-being in young adults. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e69841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Heffer, T.; Good, M.; Daly, O.; MacDonell, E.; Willoughby, T. The longitudinal association between social-media use and depressive symptoms among adolescents and young adults: An empirical reply to Twenge et al. (2018). Clin. Psychol. Sci. 2019, 7, 462–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Best, P.; Manktelow, R.; Taylor, B. Online communication, social media and adolescent wellbeing: A systematic narrative review. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2014, 41, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fegert, J.M.; Vitiello, B.; Plener, P.L.; Clemens, V. Challenges and burden of the Coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic for child and adolescent mental health: A narrative review to highlight clinical and research needs in the acute phase and the long return to normality. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2020, 14, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ford, T.; John, A.; Gunnell, D. Mental health of children and young people during pandemic. Br. Med. J. Publ. Group 2021, 372, n614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Octavius, G.S.; Silviani, F.R.; Lesmandjaja, A.; Angelina; Juliansen, A. Impact of COVID-19 on adolescents’ mental health: A systematic review. Middle East Curr. Psychiatry 2020, 27, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Sullivan, K.; Clark, S.; McGrane, A.; Rock, N.; Burke, L.; Boyle, N.; Joksimovic, N.; Marshall, K. A qualitative study of child and adolescent mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic in Ireland. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, M.; Jiang, J. Teens, social media & technology 2018. Pew Res. Cent. 2018, 31, 1673–1689. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Y.; Qian, Y. COVID-19 and adolescent mental health in the United Kingdom. J. Adolesc. Health 2021, 69, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinlay, A.R.; May, T.; Dawes, J.; Fancourt, D.; Burton, A. ‘You’re just there, alone in your room with your thoughts’: A qualitative study about the psychosocial impact of the COVID-19 pandemic among young people living in the UK. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e053676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branquinho, C.; Kelly, C.; Arevalo, L.C.; Santos, A.; Gaspar de Matos, M. Hey, “we also have something to say”: A qualitative study of Portuguese adolescents’ and young people’s experiences under COVID-19. J. Community Psychol. 2020, 48, 2740–2752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, S.R.; Rivera, K.M.; Rushing, E.; Manczak, E.M.; Rozek, C.S.; Doom, J.R. “I Hate This”: A qualitative analysis of adolescents’ self-reported challenges during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Adolesc. Health 2021, 68, 262–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, M.S.; Koşan, Y. The psychological impact of COVID-19 on university students: Their expectations of mental health professionals. Int. J. Psychol. Educ. Stud. 2021, 8, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costello, E.J.; Angold, A. Scales to assess child and adolescent depression: Checklists, screens, and nets. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 1988, 27, 726–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jarbin, H.; Ivarsson, T.; Andersson, M.; Bergman, H.; Skarphedinsson, G. Screening efficiency of the Mood and Feelings Questionnaire (MFQ) and Short Mood and Feelings Questionnaire (SMFQ) in Swedish help seeking outpatients. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0230623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thabrew, H.; Stasiak, K.; Bavin, L.M.; Frampton, C.; Merry, S. Validation of the Mood and Feelings Questionnaire (MFQ) and Short Mood and Feelings Questionnaire (SMFQ) in New Zealand help-seeking adolescents. Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res. 2018, 27, e1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Russell, D.; Peplau, L.A.; Ferguson, M.L. Developing a measure of loneliness. J. Personal. Assess. 1978, 42, 290–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E.D.; Emmons, R.A.; Larsen, R.J.; Griffin, S. The satisfaction with life scale. J. Personal. Assess. 1985, 49, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jenkins-Guarnieri, M.A.; Wright, S.L.; Johnson, B. Development and validation of a social media use integration scale. Psychol. Pop. Media Cult. 2013, 2, 38–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W.; Poth, C.N. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing among Five Approaches; Sage: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Shenton, A.K. Strategies for ensuring trustworthiness in qualitative research projects. Educ. Inf. 2004, 22, 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Patton, M.Q. Qualitative Research & Evaluation Methods: Integrating Theory and Practice; Sage: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Grbich, C. Qualitative Data Analysis: An Introduction; Sage: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Miles, M.B.; Huberman, A.M. Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook; Sage: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W.; Creswell, J.D. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches; Sage: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln, Y.S.; Guba, E.G. But is it rigorous? Trustworthiness and authenticity in naturalistic evaluation. New Dir. Program Eval. 1986, 1986, 73–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, C.; Joffe, H. Intercoder reliability in qualitative research: Debates and practical guidelines. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2020, 19, 1609406919899220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burla, L.; Knierim, B.; Barth, J.; Liewald, K.; Duetz, M.; Abel, T. From text to codings: Intercoder reliability assessment in qualitative content analysis. Nurs. Res. 2008, 57, 113–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W.; Plano Clark, V. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research, 3rd ed.; Sage: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Guetterman, T.C.; Fetters, M.D.; Creswell, J.W. Integrating quantitative and qualitative results in health science mixed methods research through joint displays. Ann. Fam. Med. 2015, 13, 554–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Achterbergh, L.; Pitman, A.; Birken, M.; Pearce, E.; Sno, H.; Johnson, S. The experience of loneliness among young people with depression: A qualitative meta-synthesis of the literature. BMC Psychiatry 2020, 20, 415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Divin, N.; Harper, P.; Curran, E.; Corry, D.; Leavey, G. Help-seeking measures and their use in adolescents: A systematic review. Adolesc. Res. Rev. 2018, 3, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gulliver, A.; Griffiths, K.M.; Christensen, H. Perceived barriers and facilitators to mental health help-seeking in young people: A systematic review. BMC Psychiatry 2010, 10, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gunnell, D.; Kidger, J.; Elvidge, H. Adolescent mental health in crisis. Br. Med. J. Publ. Group 2018, 361, k2608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Modecki, K.L.; Duvenage, M.; Uink, B.; Barber, B.L.; Donovan, C.L. Adolescents’ online coping: When less is more but none is worse. Clin. Psychol. Sci. 2021, 10, 467–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.Y. How do people compare themselves with others on social network sites?: The case of Facebook. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 32, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, S.S.; Lee, E.W.; Liao, Y. Social network sites, friends, and celebrities: The roles of social comparison and celebrity involvement in adolescents’ body image dissatisfaction. Soc. Media+ Soc. 2016, 2, 2056305116664216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chou, H.-T.G.; Edge, N. “They Are Happier and Having Better Lives than I Am”: The Impact of Using Facebook on Perceptions of Others’ Lives. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2011, 15, 117–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fernandes, B.; Biswas, U.N.; Mansukhani, R.T.; Casarín, A.V.; Essau, C.A. The impact of COVID-19 lockdown on internet use and escapism in adolescents. Rev. De Psicol. Clínica Con Niños Y Adolesc. 2020, 7, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, W.E.; Dumas, T.M.; Forbes, L.M. Physically isolated but socially connected: Psychological adjustment and stress among adolescents during the initial COVID-19 crisis. Can. J. Behav. Sci. 2020, 52, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamran, A.; Naeim, M. Managing back to school anxiety during a COVID-19 outbreak. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2021, 209, 244–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jastrowski Mano, K.E. School anxiety in children and adolescents with chronic pain. Pain Res. Manag. 2017, 2017, 8328174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-Sogorb, A.; Sanmartín, R.; Vicent, M.; Gonzálvez, C.; Ruiz-Esteban, C.; García-Fernández, J.M. School anxiety profiles in Spanish adolescents and their differences in psychopathological symptoms. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0262280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques de Miranda, D.; da Silva Athanasio, B.; Sena Oliveira, A.C.; Simoes-e-Silva, A.C. How is COVID-19 pandemic impacting mental health of children and adolescents? Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2020, 51, 101845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booker, C.L.; Kelly, Y.J.; Sacker, A. Gender differences in the associations between age trends of social media interaction and well-being among 10-15 year olds in the UK. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Orben, A.; Przybylski, A.K.; Blakemore, S.-J.; Kievit, R.A. Windows of developmental sensitivity to social media. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fancourt, D.; Steptoe, A.; Bu, F. Trajectories of anxiety and depressive symptoms during enforced isolation due to COVID-19 in England: A longitudinal observational study. Lancet Psychiatry 2021, 8, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, B. Adolescent propensity for depressed mood and help seeking: Race and gender differences. J. Ment. Health Policy Econ. 2004, 7, 133–145. [Google Scholar]

| 1. Have you used the internet for mental health information? yes or no |

| 2. If yes, how has your internet use for mental health information changed during the lockdown? on a scale of 1 to 10, 1: decreased; 10: increased. |

| 3. How has your internet use changed during COVID-19? on a scale of 1 to 10, 1: no change; 10: much increased. |

| 4. How has your mood changed during COVID-19? on a scale of 1 to 10, 1: much worse; 10: much improved. |

| 1. How has lockdown affected your mood? Can you give any examples? |

| 2. How has the internet affected your experiences during the lockdown, especially your mood? Can you give an example? |

| 3. Have you used the internet more during lockdown? If so what for? |

| 4. Have you used the internet more during lockdown for mental health information? |

| 5. Have you used the internet more during lockdown for information about COVID-19? |

| 6. When you compare your mood/life satisfaction before and during the lockdown, what would you like to say? |

| 7. Since lockdown what has affected your mood the most? Good or bad? Can you give any examples? |

| LD (N = 47) vs. HD (N = 61) | Group Difference | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nominal Data | Count | χ2 | p-Value | |

| Gender (F/M) | 30/17 | 48/13 | 2.92 | 0.08 |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| (BAME/White) | 26/21 | 29/32 | 0.64 | 0.42 |

| Education | 2.6 | 0.26 | ||

| Secondary | 2 | 5 | ||

| College | 39 | 53 | ||

| University | 6 | 3 | ||

| Use of the Internet for Mental Health Information | 21 | <0.001 | ||

| Yes | 25 | 56 | ||

| No | 22 | 5 | ||

| LD (N = 47) vs. HD (N = 61) | Group Difference | |||

| Norm Distributed Data | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | tScore | p-Value |

| MFQ | 18.68 (7.06) | 41.97 (9.74) | −13.8 | <0.001 |

| SWL | 22.30 (5.84) | 17.59 (6.20) | 4.0 | <0.001 |

| SMUIS | 37.17(8.23) | 39.18 (11.27) | −1.0 | 0.306 |

| Non-Norm Data LD vs. HD | Mann-Whitney U | p-Value |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 1333.5 | 0.43 |

| UCLA | 2245 | <0.001 |

| Mood changes during COVID-19 | 844 | <0.001 |

| Internet change COVID-19 | 1975 | 0.001 |

| Internet mental health info change | 938.5 | 0.01 |

| Main Theme | Quantitative Results (Statistics) | Findings Based on Qualitative Observation | Meta-Inferences (Interpretation) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Impact of internet use on mental health | HDs use internet more for mental health information (χ2(1 108) = 21, p < 0.001) than LDs. BAME adolescents reported increased use of the internet more than White adolescents (U = 4.45, p = 0.03). Those with increasing symptoms reported using the internet more during COVID-19 (rs = 0.34, N = 108, p < 0.001, two-tailed). Furthermore, as depression symptoms increased participants were more likely to use the internet for mental health information (rs = 0.37, N = 108, p < 0.001, two-tailed) | All participants:

| Confirmation Both groups indicated that they used the internet more for mental health at the quantitative stage and reported positive aspects of the internet for mental health at the qualitative stage. |

| Mood and life satisfaction before COVID-19 | No quantitative data before COVID-19 | Participants emphasized that school anxiety and an intense pace of life made them unhappy before COVID-19:

| Expansion The statements taken from the participants regarding COVID-19 in the qualitative phase contributed to the creation of a new main theme “pre-COVID-19”. However, in the quantitative stage, no measurement tool can directly measure the pre-pandemic period, so quantitative data on this subject could not be obtained. However, the mixed-method research fulfilled its function and contributed to revealing such an important finding that could not be reached at the quantitative stage. |

| Mood and life satisfaction During COVID-19 | HDs have lower life satisfaction t(106) = 4.01, p < 0.001 and higher loneliness levels (U = 2245, p < 0.001). As depression symptoms increase, mood during COVID-19 decreased (r = −0.44, N = 108, p < 0.001, two-tailed). | As expected, the participants emphasized that COVID-19 negatively affected their life satisfaction:

| Confirmation During COVID-19, it is observed that adolescents experience deterioration in their mood. Participants expressed the negative effects of COVID on mood more frequently, and this confirms the data obtained from the quantitative stage. |

| Mood and life satisfaction During COVID-19 | There was no statistically significant difference between genders regarding life satisfaction (p > 0.05). | Male participants pointed out the negatives of COVID-19 more than females did:

| Discordance Although life satisfaction and loneliness levels were not statistically different between males and females, the qualitative stage of the study revealed that males have a more negative perspective compared to females. |

| Mood and life satisfaction During COVID-19 | Negative relationships with the family could have caused negative aspects on adolescents’ mental health:

| Expansion The effect of family relationships on adolescents’ moods during COVID-19 was revealed in the qualitative part. Families stand out as an important factor that facilitates coping with COVID-19 but for some, families made COVID-19 more difficult. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kaya, M.S.; McCabe, C. Effects of COVID-19 on Adolescent Mental Health and Internet Use by Ethnicity and Gender: A Mixed-Method Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 8927. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19158927

Kaya MS, McCabe C. Effects of COVID-19 on Adolescent Mental Health and Internet Use by Ethnicity and Gender: A Mixed-Method Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(15):8927. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19158927

Chicago/Turabian StyleKaya, M. Siyabend, and Ciara McCabe. 2022. "Effects of COVID-19 on Adolescent Mental Health and Internet Use by Ethnicity and Gender: A Mixed-Method Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 15: 8927. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19158927

APA StyleKaya, M. S., & McCabe, C. (2022). Effects of COVID-19 on Adolescent Mental Health and Internet Use by Ethnicity and Gender: A Mixed-Method Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(15), 8927. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19158927