Explanatory Models of Burnout Diagnosis Based on Personality Factors in Primary Care Nurses

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design and Procedure

2.2. Participants

2.3. Variables and Instruments

2.4. Ethics

2.5. Statistical Methods

3. Results

3.1. Description of the Sample and Levels of the Three Dimensions of Burnout

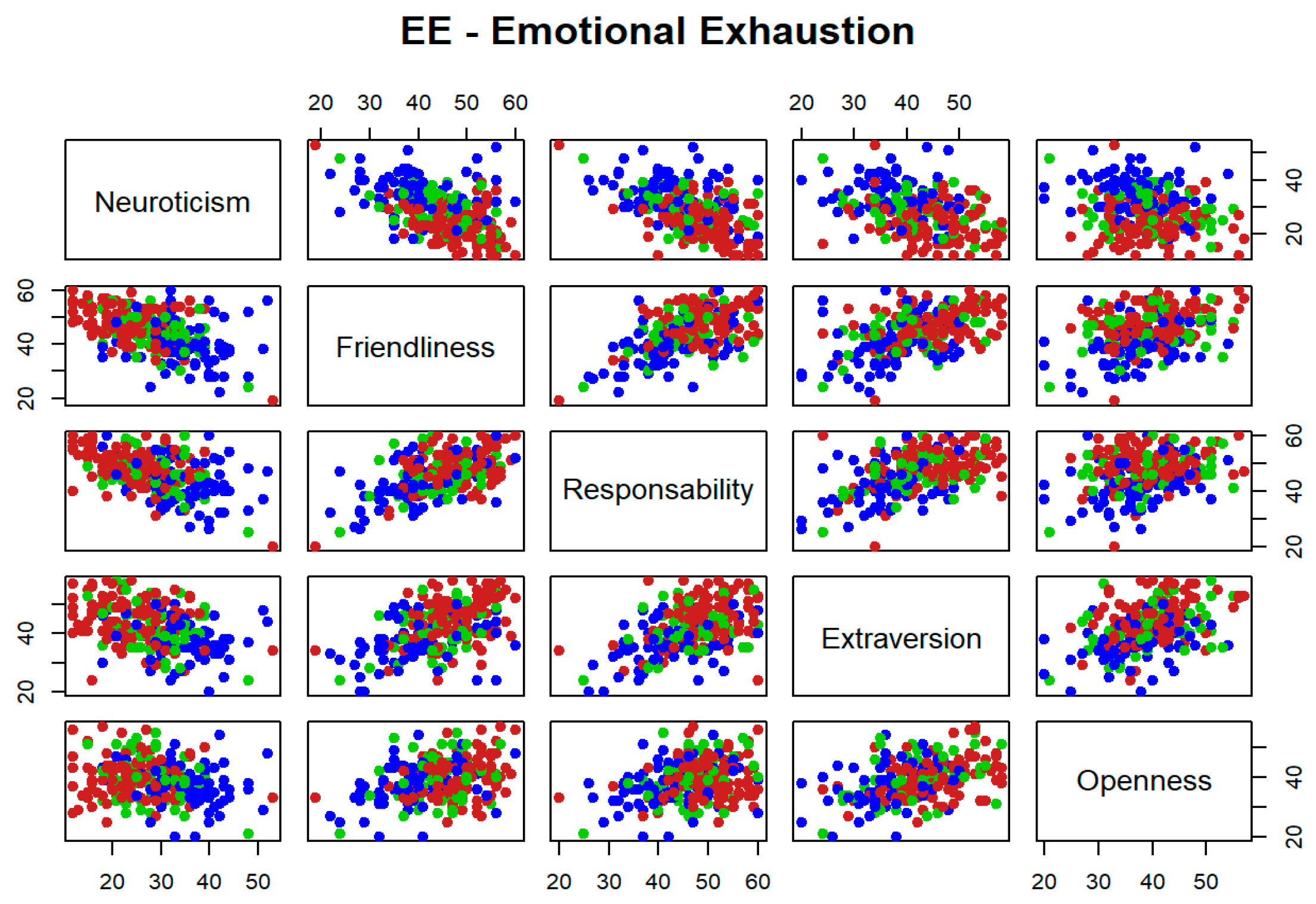

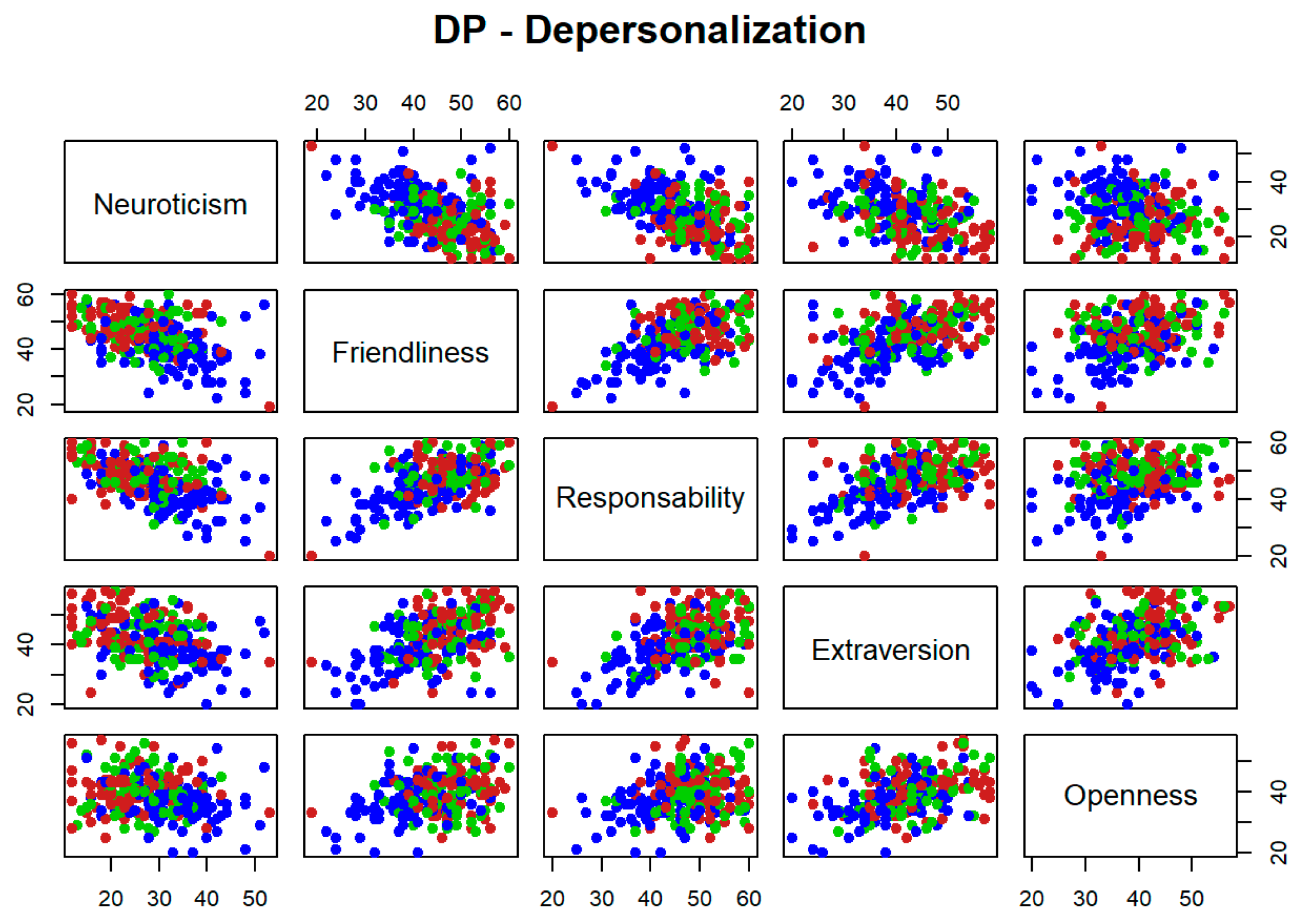

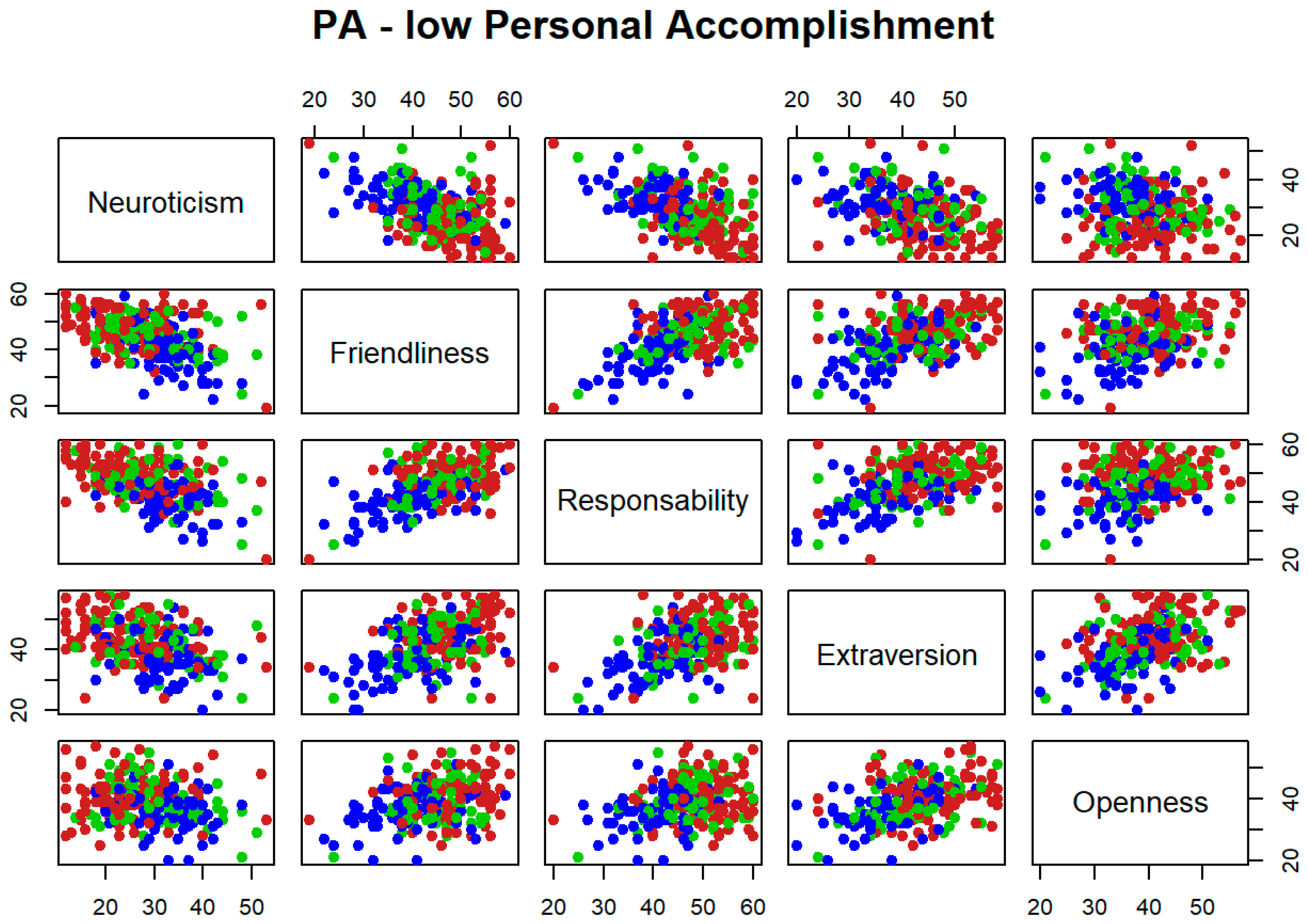

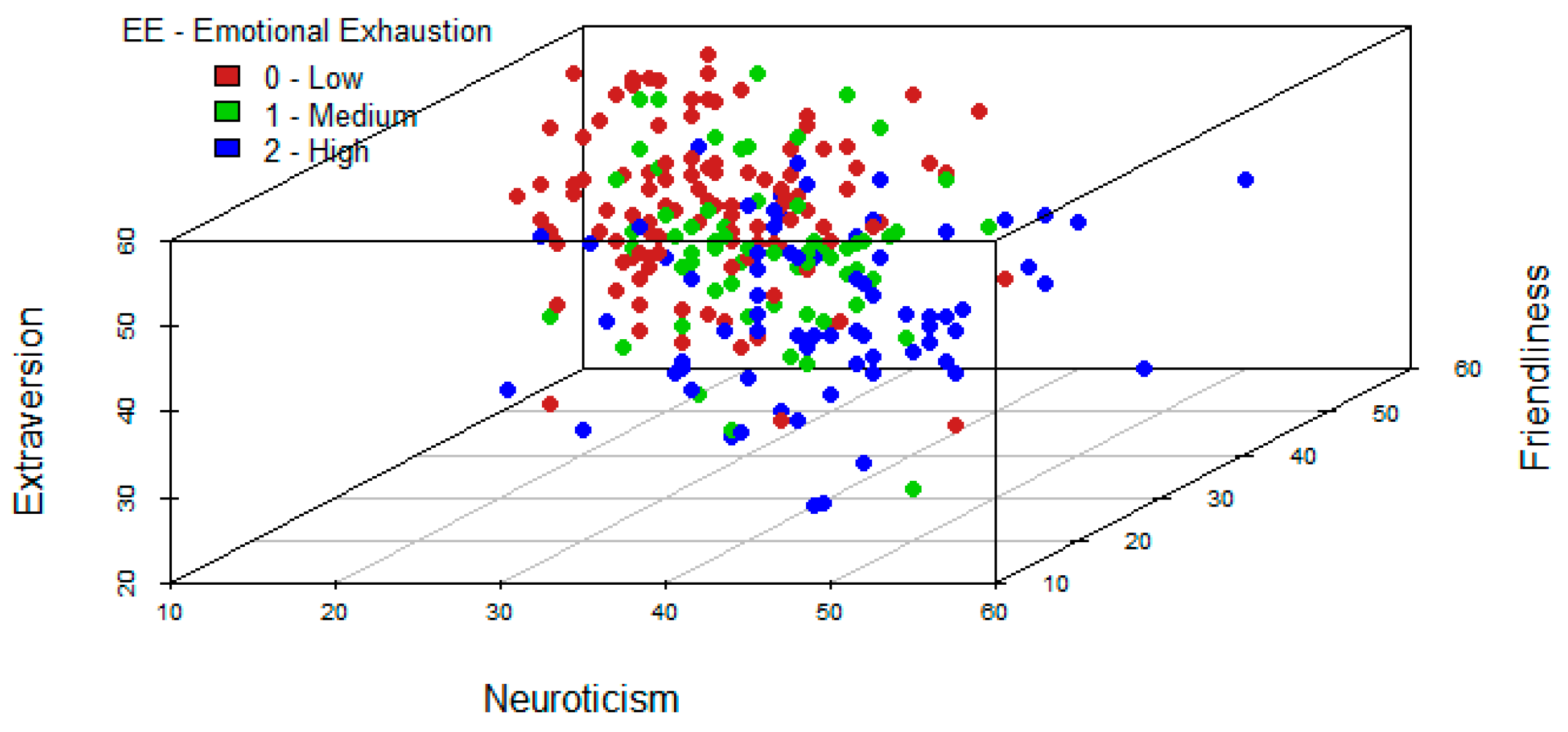

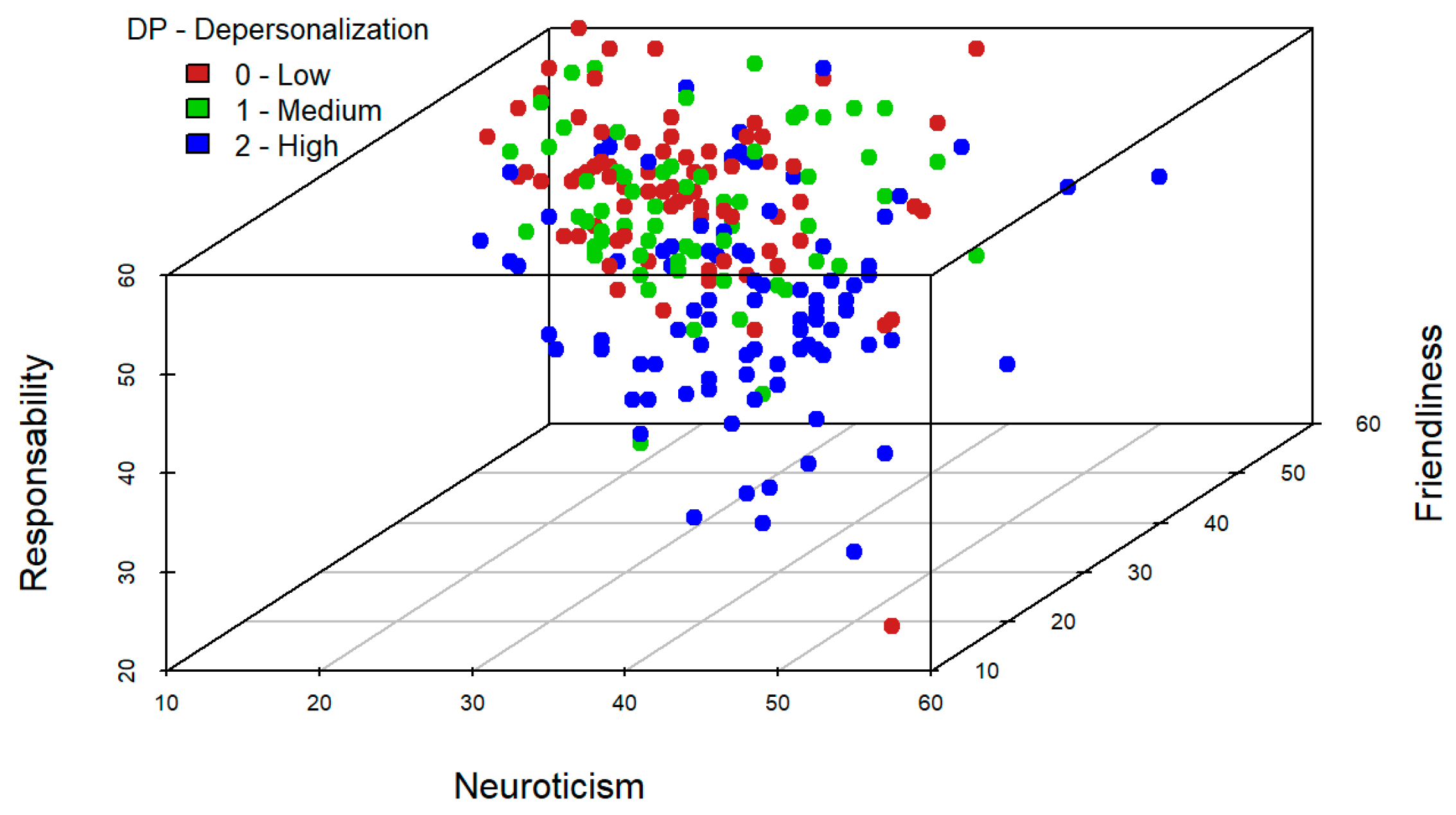

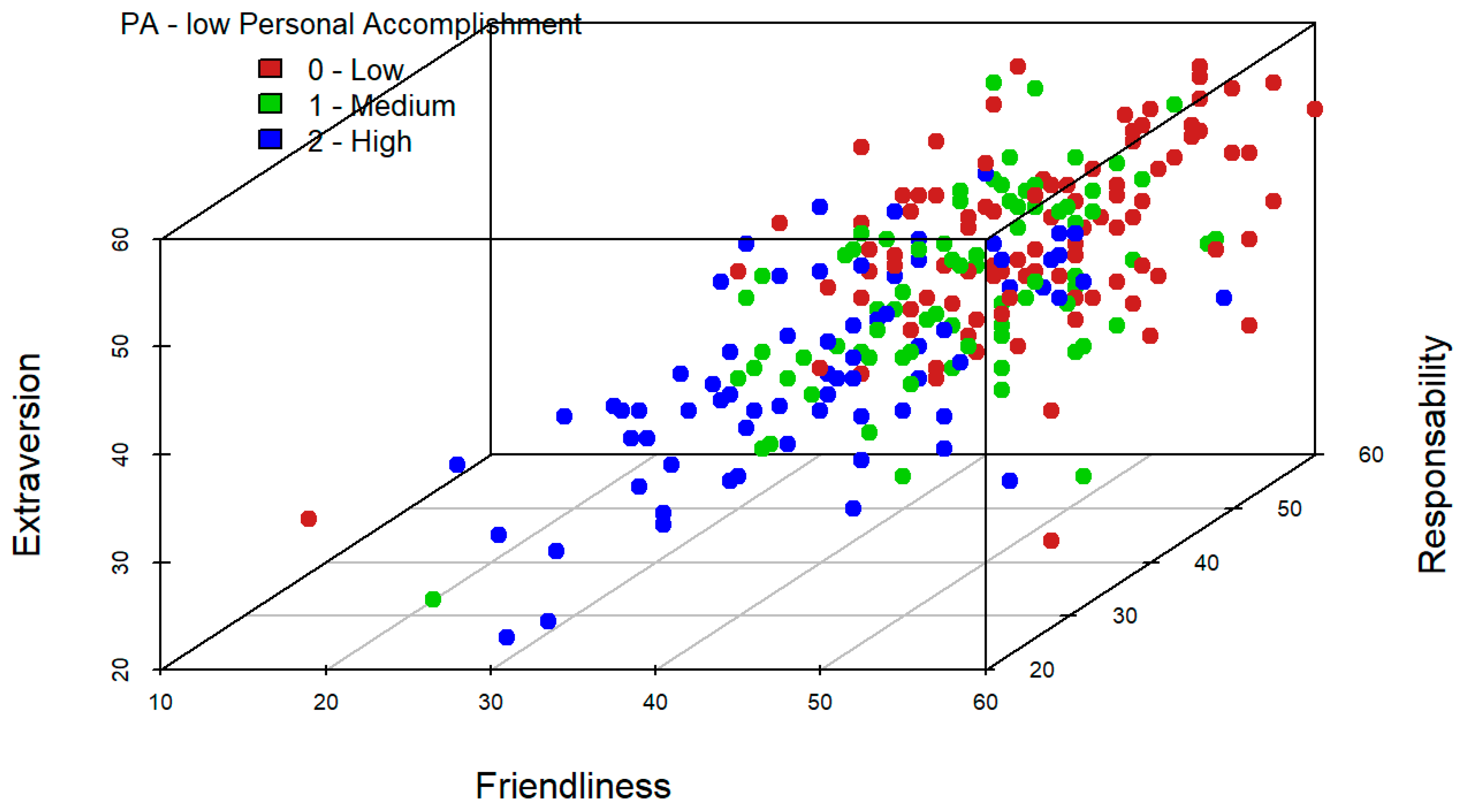

3.2. Exploratory Analysis

3.3. Explanatory Model for Each Dimension of Burnout

4. Discussion

4.1. Study Limitations

4.2. Clinical Implications

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ruiz-Fernández, M.D.; Ortega-Galán, A.M.; Fernández-Sola, C.; Hernández-Padilla, J.M.; Granero-Molina, J.; Ramos-Pichardo, J.D. Occupational factors associated with health-related quality of life in nursing professionals: A multi-centre study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-García, E.; Ortega-Galán, A.M.; Ibáñez-Masero, O.; Ramos-Pichardo, J.D.; Fernández-Leyva, A.; Ruiz-Fernández, M.D. Qualitative study on the causes and consequences of compassion fatigue from the perspective of nurses. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2021, 30, 469–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gómez-Urquiza, J.L.; Monsalve-Reyes, C.S.; San Luis-Costas, C.; Fernández- Castillo, R.; Aguayo-Estremera, R.; Cañadas-de la Fuente, G.A. Factores de riesgo y niveles de burnout en enfermeras de AP: Una revisión sistemática. Aten. Prim. 2017, 49, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cañadas-De la Fuente, G.A.; Vargas, C.; San Luis, C.; García, I.; Cañadas, G.R.; De la Fuente, E.I. Risk factors and prevalence of burnout syndrome in the nursing profession. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2015, 52, 240–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stamm, B. Measuring compassion satisfaction as well as fatigue: Developmental history of the compassion satisfaction and fatigue test. In Treating Compassion Fatigue; Brunner-Routledge: Oxford, UK, 2002; Volume 1, pp. 107–119. [Google Scholar]

- Schaufeli, W.; Leiter, M.; Maslach, C. Burnout: 35 years of research and practice. Career Dev. Int. 2009, 14, 204–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iserson, K. Burnout Syndrome: Global Medicine Volunteering as a Possible Treatment Strategy. J. Emerg. Med. 2018, 54, 516–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freudenberger, H. Staff Burn-Out. J. Soc. Issues 1974, 30, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C.; Jackson, C.E. The measurement of experienced burnout. J. Occup. Behav. 1981, 2, 99–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C.; Schaufeli, W.; Leiter, M. Job Burnout. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2001, 52, 397–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. The Bangkok Charter for Health Promotion in a Globalized World. 2005. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/28-05-2019-burn-out-an-occupational-phenomenon-international-classification-of-diseases (accessed on 15 May 2022).

- Torrente, M.; Sousa, P.A.; Sánchez-Ramos, A.; Pimentao, J.; Royuela, A.; Franco, F.; Collazo-Lorduy, A.; Menasalvas, A.; Provencio, M. To burn-out or not to burn-out: A cross-sectional study in healthcare professionals in Spain during COVID-19 pandemic. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e044945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dugani, S.; Afari, H.; Hirschhorn, L.R.; Ratcliffe, H.; Veillard, J.; Martin, G.; Lagomarsino, G.; Basu, L.; Bitton, A. Prevalence and factors associated with burnout among frontline primary health care providers in low-and middle-income countries: A systematic review. Gates Open Res. 2018, 2, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monsalve-Reyes, C.S.; San Luis-Costas, C.; Gómez-Urquiza, J.L.; Albendín-García, L.; Aguayo, R.; Cañadas-De la Fuente, G.A. Burnout syndrome and its prevalence in primary care nursing: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Fam. Pract. 2018, 19, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, W.; Pan, Z.; Li, Z.; Lu, S.; Zhang, L. Job burnout among primary healthcare workers in rural China: A multilevel analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, L.Y.; Rose, D.E.; Ganz, D.A.; Giannitrapani, K.F.; Yano, E.M.; Rubenstein, L.V.; Stockdale, S.E. Elements of the healthy work environment associated with lower primary care nurse burnout. Nurs. Outlook 2020, 68, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stehman, C.R.; Testo, Z.; Gershaw, R.S.; Kellogg, A.R. Burnout, drop out, suicide: Physician loss in emergency medicine, part I. West. J. Emerg. Med. 2019, 20, 485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melnyk, B.M. Burnout, depression and suicide in nurses/clinicians and learners: An urgent call for action to enhance professional well-being and healthcare safety. Worldviews Evid. Based Nurs. 2020, 17, 2–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jun, J.; Ojemeni, M.M.; Kalamani, R.; Tong, J.; Crecelius, M.L. Relationship between nurse burnout, patient and organizational outcomes: Systematic review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2021, 119, 103933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Membrive-Jiménez, M.J.; Gómez-Urquiza, J.L.; Suleiman-Martos, N.; Monsalve-Reyes, C.; Romero-Béjar, J.L.; Cañadas-De la Fuente, G.A.; De la Fuente-Solana, E.I. Explanatory Models of Burnout Diagnosis Based on Personality Factors and Depression in Managing Nurses. J. Pers. Med. 2022, 12, 438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De la Fuente-Solana, E.I.; Cañadas, G.R.; Ramirez-Baena, L.; Gómez-Urquiza, J.L.; Ariza, T.; Cañadas-De la Fuente, G.A. An Explanatory Model of Potential Changes in Burnout Diagnosis According to Personality Factors in Oncology Nurses. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, P.; McCrae, R. Inventario de Personalidad NEO Revisado. Inventario NEO Reducido de Cinco Factores (NEO-FFI); TEA Ediciones: Madrid, Spain, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Seisdedos, N. MBI Inventario Burnout de Maslach; TEA Ediciones: Madrid, Spain, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- World Medical Association. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects. JAMA 2013, 310, 2191–2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agresti, A. Foundations of Linear and Generalized Linear Models; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Agresti, A. Categorical Data Analysis, 3rd ed.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Geuens, N.; Van Bogaert, P.; Franck, E. Vulnerability to burnout within the nursing workforce—The role of personality and interpersonal behaviour. J. Clin. Nurs. 2017, 26, 4622–4633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ang, S.Y.; Dhaliwal, S.S.; Ayre, T.C.; Uthaman, T.; Fong, K.Y.; Tien, C.E.; Zhou, H.; Della, P. Demographics and personality factors associated with burnout among nurses in a Singapore tertiary hospital. Biomed. Res. Int. 2016, 2016, 6960184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntantana, A.; Matamis, D.; Savvidou, S.; Giannakou, M.; Gouva, M.; Nakos, G.; Koulouras, V. Burnout and job satisfaction of intensive care personnel and the relationship with personality and religious traits: An observational, multicenter, cross-sectional study. Intensive Crit. Care. Nurs. 2017, 41, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Baena, L.; Ortega-Campos, E.; Gomez-Urquiza, J.; Cañadas-De la Fuente, G.; De la Fuente-Solana, E.; Cañadas-De la Fuente, G.A. Multicentre Study of Burnout Prevalence and Related Psychological Variables in Medical Area Hospital Nurses. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biganeh, J.; Abolghasemi, J.; Alimohammadi, I.; Ebrahimi, H.; Davoud, B.; Hosseinabadi, M.B.; Ashtarinezhad, A. Influences of Occupational Burnout and Personality on Lipid Peroxidation Among Nurses in Shahroud City, Iran. J. UOEH 2021, 43, 397–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, W.Y.; Chien, L.Y.; Hwang, F.M.; Huang, N.; Chiou, S.T. From job stress to intention to leave among hospital nurses: A structural equation modelling approach. J. Adv. Nurs. 2018, 74, 677–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Søbstad, J.H.; Pallesen, S.; Bjorvatn, B.; Costa, G.; Hystad, S.W. Predictors of turnover intention among Norwegian nurses: A cohort study. Health Care Manag. Rev. 2021, 46, 367–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hewko, S.; Brown, P.; Fraser, K.; Wong, C.; Cummings, G. Factors influencing nurse managers’ intent to stay or leave: A quantitative analysis. J. Nurs. Manag. 2014, 23, 1058–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rao, H.; Mancini, D.; Tong, A.; Khan, H.; Santacruz Gutierrez, B.; Mundo, W.; Collings, A.; Cervantes, L. Frontline interdisciplinary clinician perspectives on caring for patients with COVID-19: A qualitative study. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e048712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolme, S.; Austeng, D.; Gjeilo, K.H. Task shifting of intravitreal injections from physicians to nurses: A qualitative study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2021, 21, 1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Naruse, T. Effect of time pressure on the burnout of home-visiting nurses: The moderating role of relational coordination with nursing managers. Jpn. J. Nurs. Sci. 2018, 16, 221–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yasin, Y.M.; Kerr, M.S.; Wong, C.A.; Bélanger, C.H. Factors affecting job satisfaction among acute care nurses working in rural and urban settings. J. Adv. Nurs. 2020, 76, 2359–2368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danaci, E.; Koç, Z. The association of job satisfaction and burnout with individualized care perceptions in nurses. Nurs. Ethics 2020, 27, 301–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galleta-Williams, H.; Esmail, A.; Grigoroglou, C.; Zghebi, S.S.; Zhou, A.Y.; Hodkinson, A.; Panagioti, M. The importance of teamwork climate for preventing burnout in UK general practices. Eur. J. Public Health 2020, 30, iv36–iv38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.P.; Tsai, J.M.; Lu, M.H.; Lin, L.M.; Lu, C.H.; Wang, K.K. The influence of personality traits and socio-demographic characteristics on paediatric nurses’ compassion satisfaction and fatigue. J. Adv. Nurs. 2018, 74, 1180–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega-Campos, E.; Cañadas-De la Fuente, G.A.; Albendín-García, L.; Gómez-Urquiza, J.L.; Monsalve-Reyes, C.; De la Fuente-Solana, E.I. A Multicentre Study of Psychological Variables and the Prevalence of Burnout among Primary Health Care Nurses. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.H.; Kim, S.R.; Kim, Y.O.; Kim, J.Y.; Kim, H.K.; Kim, H.Y. Influence of type D personality on job stress and job satisfaction in clinical nurses: The mediating effects of compassion fatigue, burnout, and compassion satisfaction. J. Adv. Nurs. 2017, 73, 905–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cañadas-de la Fuente, G.A.; Albendín-García, L.; Cañadas, G.R.; San Luis-Costas, C.; Ortega-Campos, E.; de la Fuente-Solana, E.I. Nurse burnout in critical care units and emergency departments: Intensity and associated factors. Emergencias 2018, 30, 328–331. [Google Scholar]

- Ortega-Campos, E.; Vargas-Román, K.; Velando-Soriano, A.; Suleiman-Martos, N.; Cañadas-De la Fuente, G.A.; Albendín-García, L.; Gómez-Urquiza, J.L. Compassion Fatigue, Compassion Satisfaction, and Burnout in Oncology Nurses: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sustainability. 2020, 12, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayala Calvo, J.; García, G. Hardiness as moderator of the relationship between structural and psychological empowerment on burnout in middle managers. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2018, 91, 362–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, F.; Raphael, D.; Mackay, L.; Smith, M.; King, A. Personal and work-related factors associated with nurse resilience: A systematic review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2019, 93, 129–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wang, Q.; Guan, C.; Luo, L.; Hu, X. Compassion fatigue and compassion satisfaction among Chinese palliative care nurses: A province-wide cross-sectional survey. J. Nurs. Manag. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable (n = 242) | M | SD |

|---|---|---|

| Nt | 28.26 | 8.20 |

| Fr | 44.72 | 7.65 |

| Ry | 46.60 | 7.22 |

| Ex | 42.01 | 7.88 |

| Op | 39.08 | 6.72 |

| Levels | EE | DP | PA | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | Medium | High | Low | Medium | High | Low | Medium | High | |

| % | 45.0 | 25.2 | 29.8 | 32.7 | 28.5 | 38.8 | 39.3 | 31.4 | 29.3 |

| M (SD) | 18.44 (12.24) | 7.69 (6.29) | 36.40 (8.92) | ||||||

| Predictor | B | SD | Wald | p | Odds | CI for 95% Odds | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||||

| −1.951 | 1.698 | 1.321 | 0.250 | 0.142 | 0.005 | 3.961 | |

| −0.349 | 1.692 | 0.043 | 0.837 | 0.705 | 0.025 | 19.423 | |

| 0.123 | 0.022 | 30.123 | <0.001 | 1.131 | 1.082 | 1.182 | |

| −0.063 | 0.024 | 6.902 | <0.001 | 0.939 | 0.896 | 0.984 | |

| Ry | −0.031 | 0.025 | 1.506 | 0.220 | 0.969 | 0.923 | 1.018 |

| −0.055 | 0.022 | 5.996 | 0.014 | 0.946 | 0.905 | 0.989 | |

| 0.037 | 0.023 | 2.541 | 0.111 | 1.038 | 0.991 | 1.086 | |

| Predictor | B | SD | Wald | p | Odds | CI for 95% Odds | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||||

| −6.898 | 1.715 | 16.185 | <0.001 | 0.001 | <0.001 | 0.03 | |

| −5.350 | 1.691 | 10.007 | <0.001 | 0.004 | <0.001 | 0.131 | |

| 0.057 | 0.020 | 8.082 | <0.001 | 1.058 | 1.018 | 1.100 | |

| −0.082 | 0.023 | 12.379 | <0.001 | 0.921 | 0.880 | 0.964 | |

| Ry | −0.048 | 0.024 | 4.135 | 0.042 | 0.953 | 0.909 | 0.998 |

| −0.014 | 0.021 | 0.481 | 0.488 | 0.986 | 0.946 | 1.026 | |

| −0.026 | 0.022 | 1.389 | 0.239 | 0.974 | 0.933 | 1.017 | |

| Predictor | B | SD | Wald | p | Odds | CI for 95% Odds | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||||

| −10.215 | 1.809 | 31.871 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.001 | |

| −8.350 | 1.766 | 22.359 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.007 | |

| 0.022 | 0.020 | 1.181 | 0.277 | 1.021 | 0.982 | 1.062 | |

| −0.065 | 0.023 | 7.790 | <0.001 | 0.937 | 0.895 | 0.980 | |

| Ry | −0.100 | 0.025 | 16.057 | <0.001 | 0.904 | 0.861 | 0.950 |

| −0.055 | 0.021 | 6.567 | 0.010 | 0.946 | 0.908 | 0.987 | |

| −0.008 | 0.022 | 0.129 | 0.719 | 0.992 | 0.949 | 1.036 | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Albendín-García, L.; Suleiman-Martos, N.; Ortega-Campos, E.; Aguayo-Estremera, R.; Romero-Béjar, J.L.; Cañadas-De la Fuente, G.A. Explanatory Models of Burnout Diagnosis Based on Personality Factors in Primary Care Nurses. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 9170. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19159170

Albendín-García L, Suleiman-Martos N, Ortega-Campos E, Aguayo-Estremera R, Romero-Béjar JL, Cañadas-De la Fuente GA. Explanatory Models of Burnout Diagnosis Based on Personality Factors in Primary Care Nurses. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(15):9170. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19159170

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlbendín-García, Luis, Nora Suleiman-Martos, Elena Ortega-Campos, Raimundo Aguayo-Estremera, José L. Romero-Béjar, and Guillermo A. Cañadas-De la Fuente. 2022. "Explanatory Models of Burnout Diagnosis Based on Personality Factors in Primary Care Nurses" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 15: 9170. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19159170

APA StyleAlbendín-García, L., Suleiman-Martos, N., Ortega-Campos, E., Aguayo-Estremera, R., Romero-Béjar, J. L., & Cañadas-De la Fuente, G. A. (2022). Explanatory Models of Burnout Diagnosis Based on Personality Factors in Primary Care Nurses. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(15), 9170. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19159170