A Free-Market Environmentalist Enquiry on Spain’s Energy Transition along with Its Recent Increasing Electricity Prices

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Policy Debate: Why Spain Needs a Free-Market Energy Transition?

2.1. The Theory of Free-Market Environmentalism

2.2. Introduction of Spain’s General Energy Transition

2.3. Literature Review on Spain’s Energy Policy: Pro-Interventionism

2.4. Literature Review on Spain’s Energy Policy: Pro-Market

2.5. Literature Review on the Proposals of Spain’s Free-Market Energy Transition

2.6. An Overlook of Different Policy Approach: How to Cover the Research Gap?

| Main Points | Deficiencies and Problems | |

|---|---|---|

| Free-Market Environmentalism |

|

|

| Pro-Interventionism |

|

|

| Pro-Market |

|

|

| Spain’s Free-Market Energy Transition |

|

|

3. Data Analysis and Method

3.1. Measured Statistic Parameters: A Comparison with Germany and the United Kingdom’s RE Transition

| Spain | Germany | The UK | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Energy system | A mixed decision-making system. The central government plays a more decision-making role in energy policy than the autonomous communities. A top-down state planning and state funding institution are missing the functions of bottom-up entrepreneurial initiatives. | A decentralized system with considerable government and civil society involvement in the energy transition. A combination of top-down and bottom-up actions. | Hypothetically the most market-oriented policymaking lacks bottom-up initiatives. Instead, the top-down processes play an essential role through market-oriented policies—more government intervention over time. |

| Essential energy policies | State research institutions have conducted main energy R&D policy and guidance since 2007 [4,73]. Support enhances economic development and job creation through RE innovation [73]. There is a strong focus on green hydrogen, energy storage, and RE innovation in mobility and industry [4]. The FIT-FIP systems (1997–2012).The liberalization of the electricity market (1998). | Support for wind energy through FIT and tax breaks. Solar PV supports through investment subsidies, low-interest loans, and FIT [57]. FIT system (1992–present). The liberalization of the electricity market (1998). | A national program to support R&D started in 1975 [22]. Liberalization of the electricity market (1989). Tendering system NFFO (1990–2002). RO system, green certificates (2002–present). FIT system (2010–present). |

| Taxation, state industry access restrictions, and state subsidies | A high electricity tax is more than 50% (see Section 4.2). State subsidy-taxation (FIT) and price control (FIP) [74] till 2012–2013. High hidden taxation on electricity. Subsidies for electrical products, oil, and nuclear closure in the current institutions, while coal subsidies ceased in 2018 [2]. Decades of strong state access restrictions in energy and RE industries [32]. | A high electricity tax is more than 60% [7]. At different rates, energy tax on oil products, natural gas, and coal and coke products. Several tax concessions (e.g., heating fuels, electricity in manufacturing industries, and agriculture). Biofuels are subsidized through the EU biofuels targets. Carbon tax for emissions in non-ETS sectors. Surcharge for consumer electricity bills to pay for renewables subsidies. The high share of costs onto households [58]. | Low electricity tax as 5% [7]. Levy control framework (LFC) for low-carbon electricity costs levied on consumers’ bills (it covers electricity only). In 2017, the Control for Low Carbon Levies replaced the LFC. Climate Change Levy (2001) levied energy supply to business and public sector consumers [60]. |

| Impact on innovation | |||

| Share of renewables in gross electricity production | 14.6% (2005) 43.46% (2020) Δ% = 29% | 11.32% (2005) 44.9% (2020) Δ% = 34% | 4.99% (2005) 42.3% (2020) Δ% = 37% |

| Share of renewables in gross available energy | 8.5% (2005) 20% (2020) Δ = 11.6% | 6.7% (2005) 18% (2020) Δ = 11.3% | 1.3 (2005) 15% (2020) Δ = 13.7% |

| Jobs created (as of 2020) | 950,809 | 121,700 | 120,400 |

| Total jobs created/pop (as of 2020) | 0.002008204 | 0.001452546 | 0.001773561 |

| Impact on GHG emissions (2005–2020) | −30.7% | −20.3% | −37.2% |

| Impact on electricity prices | |||

| Non-household consumer prices (2009–2020) | 2.9% | 44.9% | 45.6% |

| Household consumer prices | 46.6% | 40.2% | 50.3% |

3.2. Model Analysis of Spain’s Electricity Prices

- An autoregressive process (AR) is a random process for general cases of variability over time.

- Integrated (I): a time series is integrated of order 1, that is I (1), if its first differences are stationary. Similarly, if a time series is I (2), its second difference is stationary. Therefore, if a time series must be differentiated d times to make it static and then apply a weapon model (p, q), the series is said to be an ARIMA (p, d, q), that is, an integrated moving average autoregressive time series. Where p is the autoregressive terms, q is the moving average terms, and d is the number of times the time series must be differenced to make it stationary.

- Moving Average (MA): Calculated to smooth the volatility of a data series by averaging subsets of the entire series.

- Straightforward methodology, where mathematical and statistical processes are included.

- The empirical application that these models have for sample situations.

- These models have been demonstrated to bring efficiency in predicting the series in the short term.

4. Results: A State Interventionist RE Institutions with Mixed Decision-Making Features

4.1. Top-Down Initiatives and a Mixed Energy Transition Result

4.2. The FIT-FIP Systems: A Mixed State Interventionist Energy Institutions

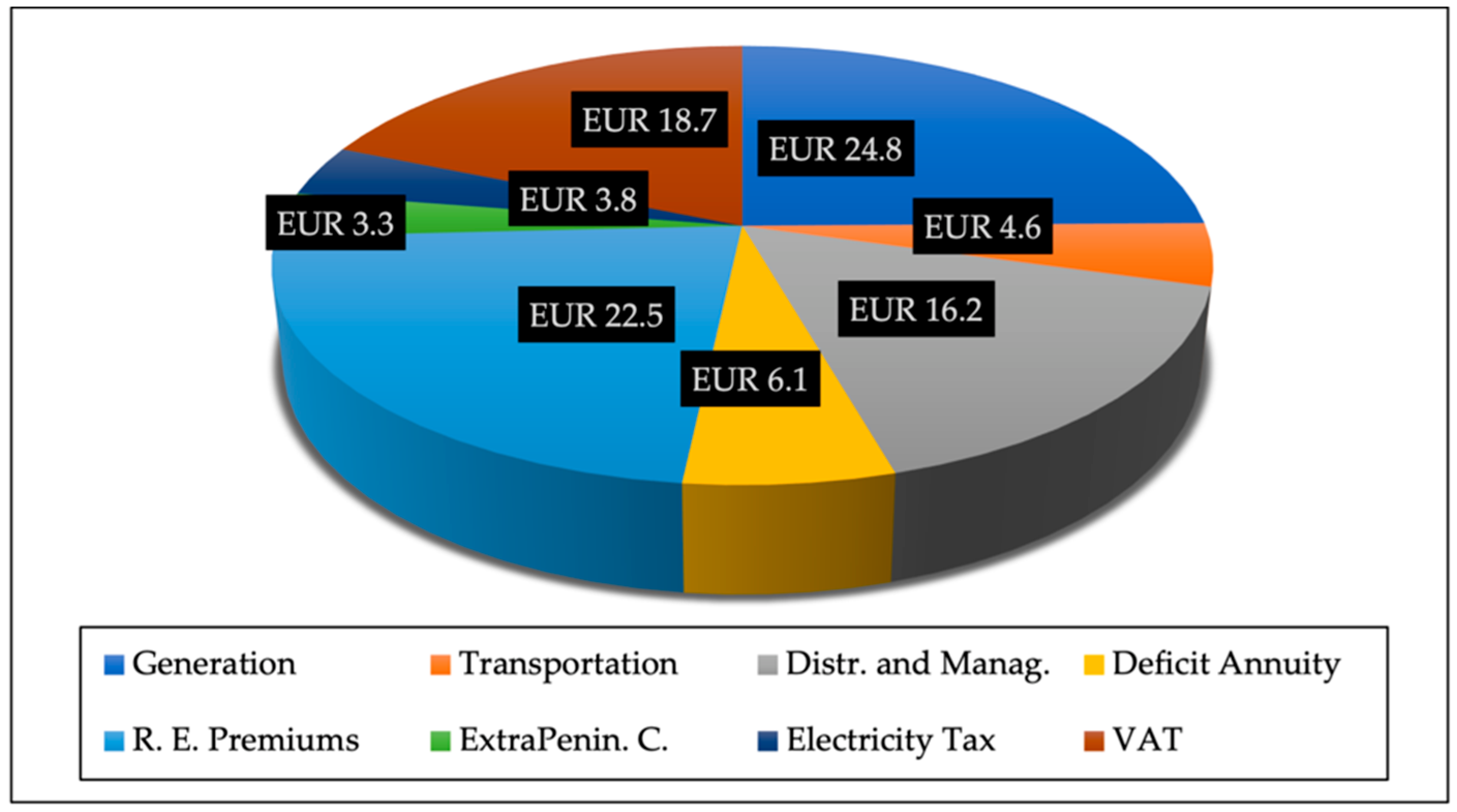

4.3. Electricity Prices, High Taxation Level, and Energy Cost in the Post-Pandemic Era

4.4. State Subsidies

4.5. Industrial Access Restrictions

5. Discussion: Reform Agenda, Research Limitation, and Future Research

5.1. Reform Agenda

5.2. Research Limitation and Potential Future Research

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Libremercado; Agencias. Los precios industriales se disparan un 31, 9% en octubre, su mayor alza en 45 años. Available online: https://www.libremercado.com/2021-10-26/los-precios-industriales-se-disparan-un-236-en-septiembre-su-mayor-alza-en-44-anos-por-la-energia-6831010 (accessed on 18 July 2021).

- International Energy Agency. Energy Policy Review Spain 2021; International Energy Agency: Paris, France, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Energy union. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/energy/topics/energy-strategy/energy-union_en (accessed on 18 July 2021).

- Barrella, R. National Strategy against Energy Poverty 2019–2024 in Spain. Available online: http://www.eppedia.eu/sites/default/files/2021-01/Barrella_2021_National%20Strategy%20against%20fuel%20poverty%20in%20Spain_EP-pedia.pdf (accessed on 18 July 2021).

- Ciarreta, A.; Pizarro-Irizar, C.; Zarraga, A. Renewable energy regulation and structural breaks: An empirical analysis of Spanish electricity price volatility. Energy Econ. 2020, 88, 104749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Red Eléctrica. This Year Spain Is Poised to Surpass the Renewable Generation Record Set in a Historic 2020. Available online: https://www.ree.es/en/press-office/news/press-release/2021/06/this-year-spain-poised-surpass-renewable-generation-record-set-in-historic-2020 (accessed on 18 July 2021).

- Wang, W.H.; Moreno-Casas, V.; Huerta de Soto, J. A Free-Market Environmentalist Transition toward Renewable Energy: The Cases of Germany, Denmark, and the United Kingdom. Energies 2021, 14, 4659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huerta de Soto, J. Entrepreneurship and the Theory of Free Market Environmentalism. In The Theory of Dynamic Efficiency; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 94–99. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, T.L.; Baden, J.; Block, W.; Borcherding, T.; Chant, J.; Dolan, E.; McFetridge, D.; Rothbard, M.N.; Smith, D.; Shaw, J.; et al. Economics and the Environment: A Reconciliation; Block, W., Ed.; The Fraser Institute: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Rothbard, M.N. Law, Property Rights, and Air Pollution. Cato J. 1982, 2, 55–99. [Google Scholar]

- Reimers, P. Monarchy, Democracy and Private Property Order How Human Rights Have Been Violated and How to Protect Them A Response to Hans H Hoppe, F A Hayek, and Elinor Ostrom. Rev. Procesos Merc. 2019, 16, 177–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller, E.W. The Non-Aggression Principle: A Short History. Rev. Procesos Merc. 2019, 16, 31–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reimers, P. An Austrian School View on Eucken’s Ordoliberalism. Analyzing the Roots and Concept of German Ordoliberalism from the Perspective of Austrian School Economics. Rev. Procesos Merc. 2020, 17, 13–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinosa, V.I.; Wang, W.H.; Zhu, H. Israel Kirzner On Dynamic Efficiency And Economic Development. Procesos Merc. Rev. Eur. Econ. Política 2020, 17, 283–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kämpe, J. Individual secession and extraterritoriality. Rev. Procesos Merc. 2013, 10, 195–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoppe, H.-H. A Realistic Libertarianism. Rev. Procesos Merc. 2015, 12, 203–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guido Hülsmann, J. On the Renaissance of Socialism. Rev. Procesos Merc. 2022, 18, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Mises, L. Human Action: A Treatise on Economics; Ludwig von Mises Institute: Auburn, AL, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Foss, N.J.; Klein, P.G. Organizing Entrepreneurial Judgment: A New Approach to the Firm; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2012; ISBN 9781139021173. [Google Scholar]

- Merino, J.B. Teoría del intercambio. Propuesta de una nueva teoría de los cambios interpersonales basada en tres elementos más simples. Rev. Procesos Merc. 2015, 12, 143–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boettke, P.J.; Coyne, C.J.; Leeson, P.T. Institutional Stickiness and the New Development Economics. Am. J. Econ. Sociol. 2008, 67, 331–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Boettke, P.J. Economics and Public Administration. South. Econ. J. 2018, 84, 938–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchanan, J.M.; Tullock, G. The Calculus of Consent: Logical Foundations of Constitutional Democracy; University of Michigan Press: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 1962; ISBN 978-0-472-06100-6. [Google Scholar]

- Hayek, F.A. The Use of Knowledge in Society. Am. Econ. Rev. 1945, 35, 519–530. [Google Scholar]

- Huerta de Soto, J. Socialism, Economic Calculation and Entrepreneurship; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Taboada, A.A. El papel del Estado en las guerras de cuarta generación bajo la óptica de la teoría de la eficiencia dinámica. Rev. Procesos Merc. 2017, 14, 13–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- España-Contreras, A. Una aproximación praxeológica a la energía. Rev. Procesos Merc. 2011, 8, 113–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calzada-Álvarez, G.; Merino Jara, R.; Rallo Julián, J.R.; García Bielsa, J.I. Study of the effects on employment of public aid to renewable energy sources. Rev. Procesos Merc. 2010, 7, 13–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reimers, P. The Subsidized Green Revolution: The Impact of Public Incentives on the Automotive Industry to Promote Alternative Fuel Vehicles (AFVs) in the Period from 2010 to 2018. Energies 2021, 14, 5765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Follert, F.; Gleißner, W.; Möst, D. What Can Politics Learn from Management Decisions? A Case Study of Germany’s Exit from Nuclear Energy after Fukushima. Energies 2021, 14, 3730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peña-Ramos, J.A.; del Pino-García, M.; Sánchez-Bayón, A. The Spanish Energy Transition into the EU Green Deal: Alignments and Paradoxes. Energies 2021, 14, 2535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinosa, V.I.; Peña-Ramos, J.A.; Recuero-López, F. The Political Economy of Rent-Seeking: Evidence from Spain’s Support Policies for Renewable Energy. Energies 2021, 14, 4197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jörgens, H.; Solorio, I. The EU and the Promotion of Renewable Energy: An Analytical Framework; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2017; ISBN 9781783471553. [Google Scholar]

- Börzel, T.A.; Risse, T. When Europe Hits Home: Europeanization and Domestic Change. Eur. Integr. Online Pap. 2000, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hoppe, T.; van Bueren, E. From Frontrunner to Laggard: The Netherlands and Europeanization in the Cases of RES-E and Biofuel Stimulation. In A Guide to EU Renewable Energy Policy: Comparing Europeanization and Domestic Policy Change in EU Member States; Solorio, I., Jörgens, H., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2017; pp. 65–84. [Google Scholar]

- Mendiluce, M.; Pérez-Arriaga, I.; Ocaña, C. Comparison of the evolution of energy intensity in Spain and in the EU15. Why is Spain different? Energy Policy 2010, 38, 639–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schallenberg-Rodriguez, J.; Haas, R. Fixed feed-in tariff versus premium: A review of the current Spanish system. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2012, 16, 293–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, C.W.; Dai, K.; Ullah, S.; Andlib, Z. COVID-19 Pandemic and Unemployment Dynamics in European Economies. Econ. Res. Ekon. Istraz. 2021, 35, 1752–1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CNMC. Electricity Retail Market Monitoring Report; Comisión Nacional de los Mercados y la Competencia: Madrid, Spain, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- IEA. Energy Prices and Taxes for OECD Countries: Country Notes, 4th ed.; IEA: Paris, France, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Mugaloglu, E.; Polat, A.Y.; Dogan, A.; Tekin, H. Oil Price Shocks During the COVID-19 Pandemic—Evidence From United Kingdom Energy Stocks. Energy Res. Lett. 2021, 2, 24253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemrit, W.; Benlagha, N. Does renewable energy index respond to the pandemic uncertainty? Renew. Energy 2021, 177, 336–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, A. Energy Prices: In Spain, Wave of Protests over Price Hikes Puts a Damper on Recovery; El País: Madrid, Spain, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Obregón, C.; Arcos, J.M. La inflación Española Subirá a Tasas del 10% ya en el Mes de Marzo. El Econ; Editorial Ecoprensa, S.A.: Madrid, Spain, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Abdelradi, F.; Serra, T. Asymmetric price volatility transmission between food and energy markets: The case of Spain. Agric. Econ. 2015, 46, 503–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MIET. Orden IET/843/2012, 2012.

- MIET. Resolución de 28 de junio de 2012, 2012.

- Jimenez, A. Casi el 60% del Recibo de la luz son Impuestos. Available online: https://www.elblogsalmon.com/sectores/casi-el-60-del-recibo-de-la-luz-son-impuestos (accessed on 22 February 2022).

- Álvarez, C.; Clemente, Y.; Alonso, A. Cómo Afecta en mi Factura de la luz la Subida del Precio del Megavatio Hora; El País: Madrid, Spain, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz, R. El Coste de la Energía sí que Importa: Ya Supone la Mitad del Recibo de la luz que Pagan los Hogares; El País: Madrid, Spain, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez de la Cruz, D. España está Entre los países con más Impuestos en el Recibo de la luz. Libr. Merc.; Libertad Digital, S.A.: Madrid, Spain, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Jefatura del Estado. Ley 54/1997 del Sector Eléctrico, 1997.

- Fisher, M.; Liou, J. How Can Nuclear Replace Coal in the Clean Energy Transition? Available online: https://www.iaea.org/newscenter/news/how-can-nuclear-replace-coal-as-part-of-the-clean-energy-transition (accessed on 26 November 2021).

- Paillere, H.; Donovan, J. IAEA and IEA Agree to Boost Cooperation on Nuclear Power for Clean Energy Transition. Available online: https://www.iaea.org/newscenter/news/iaea-and-iea-agree-to-boost-cooperation-on-nuclear-power-for-clean-energy-transition (accessed on 26 November 2021).

- Quintero, L. Amenaza la obsesión renovable el suministro? “Si planteas una nuclear no te financia nadie”—Libre Mercado. 2021. Available online: https://www.libremercado.com/2021-11-25/apagones-la-estrategia-renovable-margina-la-garantia-de-suministro-6840944/?_ga=2.266945870.1583067106.1659413399-529280362.1659413397 (accessed on 26 November 2021).

- European Commission. EU Taxonomy: Complementary Climate Delegated Act; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Labandeira, X.; Labeaga, J.M.; Rodríguez, M. Green tax reforms in Spain. Eur. Environ. 2004, 14, 290–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEA. Germany 2020; IEA: Paris, France, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- OECD; IEA. Energy Policies of IEA Countries: Denmark 2017 Review; IEA: Paris, France, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- IEA. Energy Policies of IEA Countries: United Kingdom 2019 Review; IEA: Paris, France, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Montoya, F.G.; Aguilera, M.J.; Manzano-Agugliaro, F. Renewable energy production in Spain: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2014, 33, 509–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, M.J.; Stephens, J.C. Political power and renewable energy futures: A critical review. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2018, 35, 78–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heras-Saizarbitoria, I.; Sáez, L.; Allur, E.; Morandeira, J. The emergence of renewable energy cooperatives in Spain: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 94, 1036–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couture, T.; Gagnon, Y. An analysis of feed-in tariff remuneration models: Implications for renewable energy investment. Energy Policy 2010, 38, 955–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langniß, O.; Diekmann, J.; Lehr, U. Advanced mechanisms for the promotion of renewable energy—Models for the future evolution of the German Renewable Energy Act. Energy Policy 2009, 37, 1289–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chen, D.; Gao, H.; Ma, Y. Human Capital-Driven Acquisition: Evidence from the Inevitable Disclosure Doctrine. Manage. Sci. 2020, 67, 4643–4664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Shi, D.; Zhao, B. Does good luck make people overconfident? Evidence from a natural experiment in the stock market. J. Corp. Financ. 2021, 68, 101933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, Q.; Gao, S.; Shang, Y.; Wang, B. Assessment of the sustainability of Gymnocypris eckloni habitat under river damming in the source region of the Yellow River. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 778, 146312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quan, Q.; Liang, W.; Yan, D.; Lei, J. Influences of joint action of natural and social factors on atmospheric process of hydrological cycle in Inner Mongolia, China. Urban Clim. 2022, 41, 101043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Liu, H.; Ma, K.; Yang, B.; Guerrero, J.M. An Optimization Strategy of Price and Conversion Factor Considering the Coupling of Electricity and Gas Based on Three-Stage Game. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2022, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, T.L.; Leal, D.R. Free Market Environmentalism Revised Edition; Palgrave Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Eurostat. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat (accessed on 27 June 2022).

- European Commission. Integrated National Energy and Climate Plan 2021-2030; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- European Environment Agency. Energy Support Measures, Case Study—Spain; European Environment Agency: Openhagen, Denmark, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Gujarati, D.N.; Porter, D.C.; Gunasekar, S. Basic Econometrics, 6th ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Box, G.E.P.; Jenkins, G.M.; Reinsel, G.C.; Ljung, G.M. Time Series Analysis: Forecasting and Control, 2nd ed.; Holden Day: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández, R. Electricidad: Precio Medio Final España 2010–2022. Available online: https://es.statista.com/estadisticas/993787/precio-medio-final-de-la-electricidad-en-espana/ (accessed on 27 June 2022).

- IEA Energy Technology RD&D 2020. Available online: https://www.iea.org/data-and-statistics (accessed on 30 November 2021).

- European Commission. European Commission Energy Union Indicators. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/energy/data-analysis/energy-union-indicators/scoreboard_en?dimension=Research%2C+innovation+and+competitiveness (accessed on 30 November 2021).

- OECD. OECD Economic Surveys: Spain 2021; OECD: Paris, France, 2021; ISBN 9789264882393. [Google Scholar]

- Gürtler, K.; Postpischil, R.; Quitzow, R. The dismantling of renewable energy policies: The cases of Spain and the Czech Republic. Energy Policy 2019, 133, 110881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MIE. Real Decreto 2366/1994, de 9 de Diciembre, Sobre Producción de Energía Eléctrica por Instalaciones Hidráulicas, de Cogeneración y Otras Abastecidas por Recursos o Fuentes de Energía Renovables. 1994. Available online: https://www.boe.es/buscar/doc.php?id=BOE-A-1994-28980 (accessed on 30 November 2021).

- Huerta de Soto, J. The Theory of Dynamic Efficiency; Routledge: London, UK, 2009; ISBN 9780429240454. [Google Scholar]

- Del Río González, P. Ten years of renewable electricity policies in Spain: An analysis of successive feed-in tariff reforms. Energy Policy 2008, 36, 2917–2929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TTeckenburg, E.; Rathmann, M.; Winkel, T.; Ragwitz, M.; Steinhilber, S.; Resch, G.; Panzer, C.; Busch, S.; Konstantinaviciute, I. Renewable Energy Policy Country Profiles. 2011 version; IEE: Brussels, Belgium, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Lesser, J.A.; Su, X. Design of an economically efficient feed-in tariff structure for renewable energy development. Energy Policy 2008, 36, 981–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothbard, M.N. Man, Economy, and State with Power and Market; Ludwig von Mises Institute: Auburn, AL, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Mankiw, N.G. Principles of Microeconomics, 8th ed.; Cengage Learning: Boston, MA, USA, 2018; ISBN 978-1305971493. [Google Scholar]

- MITC. Real Decreto 661/2007, de 25 de Mayo, por el Que se Regula la Actividad de Producción de Energía Eléctrica en Régimen Especial. 2007. Available online: https://www.boe.es/buscar/act.php?id=BOE-A-2007-10556 (accessed on 30 November 2021).

- Jefatura del Estado. Real Decreto-ley 9/2013, de 12 de Julio, por el que se Adoptan Medidas Urgentes para Garantizar la Estabilidad Financiera del Sistema Eléctrico. 2013. Available online: https://www.boe.es/buscar/doc.php?id=BOE-A-2013-7705 (accessed on 30 November 2021).

- MIET. Real Decreto 413/2014, de 6 de Junio, por el que se Regula la Actividad de Producción de Energía Eléctrica a Partir de Fuentes de Energía Renovables, Cogeneración y Residuos. 2014. Available online: https://www.boe.es/buscar/act.php?id=BOE-A-2014-6123 (accessed on 30 November 2021).

- MIET. Orden IET/1045/2014, de 16 de Junio, por la que se Aprueban los Parámetros Retributivos de las Instalaciones Tipo Aplicables a Determinadas Instalaciones de Producción de Energía Eléctrica a Partir de Fuentes de Energía Renovables, Cogeneración y Residuos. 2014. Available online: https://www.boe.es/diario_boe/txt.php?id=BOE-A-2014-6495 (accessed on 30 November 2021).

- Von Mises, L. Socialism: An Economic and Sociological Analysis; Liberty Fund: Indianapolis, IN, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.H.; Espinosa, V.I.; Peña-Ramos, J.A. Private Property Rights, Dynamic Efficiency and Economic Development: An Austrian Reply to Neo-Marxist Scholars Nieto and Mateo on Cyber-Communism and Market Process. Economies 2021, 9, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CNMC. Informes de Supervisión del Mercado Minorista de Electricidad. Available online: https://www.cnmc.es/listado/sucesos_energia_mercado_electrico_informes_de_supervision_del_mercado_minorista_de_electricidad/block/250 (accessed on 31 March 2022).

- Congress of Deputies. Memoria de Beneficios Fiscales; Congress of Deputies: Madrid, Spain, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez Molina, P. Spain Streamlines Permits for Utility Scale Solar, Supports Another 7GW under Self-Consumption. Available online: https://www.pv-magazine.com/2022/03/31/spain-streamlines-permits-for-utility-scale-solar-supports-another-7gw-under-self-consumption/ (accessed on 31 March 2022).

- Echarte Fernández, M.Á.; Náñez Alonso, S.L.; Jorge-Vázquez, J.; Reier Forradellas, R.F. Central Banks’ Monetary Policy in the Face of the COVID-19 Economic Crisis: Monetary Stimulus and the Emergence of CBDCs. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacalle, D. Monetary and Fiscal Policies in the COVID-19 Crisis. Will They Work? J. New Financ. 2021, 2, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.H. El nuevo cuarteto: Pandemia, uso del poder, inflación de los precios y ciclo económico conforman un nuevo cuarteto que merece un detallado análisis económico. Avance 2022, 20, 32–33. [Google Scholar]

- Knight, F.H. Risk, Uncertainty and Profit; Houghton Mifflin Company: Boston, MA, USA; New York, NY, USA, 1921. [Google Scholar]

- Huerta de Soto, J. A Hayekian Strategy to Implement Free Market Reforms. In The Theory of Dynamic Efficiency; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 182–199. [Google Scholar]

- The Heritage Foundation. 2022 Index of Economic Freedom—Spain; The Heritage Foundation: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Espinosa, V.I.; Wang, W.H.; de Soto, J. Principles of Nudging and Boosting: Steering or Empowering Decision-Making for Behavioral Development Economics. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.H. Efectos económicos de la guerra de Putin. Avance 2022, 21, 30–31. [Google Scholar]

- Libre Mercado. España y Portugal proponen a Bruselas topar el precio del gas en 30 euros. Available online: https://www.libremercado.com/2022-03-31/espana-y-portugal-proponen-a-bruselas-topar-el-precio-del-gas-en-30-euros-6881911 (accessed on 31 March 2022).

- Huerta de Soto, J. Money, Bank Credit, and Economic Cycles; Ludwig von Mises Institute: Auburn, AL, USA, 2006; ISBN 978-1-61016-725-3. [Google Scholar]

- Huerta de Soto, J.; Sánchez-Bayón, A.; Bagus, P. Principles of Monetary & Financial Sustainability and Wellbeing in a Post-COVID-19 World: The Crisis and Its Management. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huerta de Soto, J. The Economic Effects of Pandemics: An Austrian Analysis. Rev. Procesos Merc. 2021, 18, 13–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuznets, S. Economic growth and income inequality. Am. Econ. Rev. 1955, 45, 25–37. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández Luiña, E.; Fernández Ordóñez, S.; Wang, W.H. The Community Commitment to Sustainability: Forest Protection in Guatemala. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Model | ARIMA (1,0,1) with Non-Zero Mean | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficients: | |||

| AR1 | MA1 | Mean | |

| 0.7455 | 0.7414 | 101.533 | |

| s.e. | 0.2927 | 0.2186 | 55.8519 |

| Sigma’2 = 1347: | Log | Likelihood | −64.82 |

| Years | Endesa | Iberdrola | Naturgy | EDP | Viesgo | Repsol | HHI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2011 | 42% | 35% | 15% | 2% | 2% | 0% | 3.237 |

| 2012 | 41% | 35% | 16% | 3% | 2% | 0% | 3.173 |

| 2013 | 41% | 34% | 16% | 3% | 2% | 0% | 3.071 |

| 2014 | 39% | 33% | 17% | 3% | 2% | 0% | 2.943 |

| 2015 | 39% | 33% | 17% | 3% | 2% | 0% | 2.903 |

| 2016 | 38% | 32% | 17% | 3% | 2% | 0% | 2.796 |

| 2017 | 37% | 32% | 17% | 3% | 2% | 0% | 2.694 |

| 2018 | 37% | 32% | 15% | 3% | 2% | 0% | 2.609 |

| 2019 | 36% | 32% | 13% | 4% | 0% | 3% | 2.500 |

| Policy Implications | Corresponding Findings |

|---|---|

| Previous studies and our conclusion support the Spanish government’s phase-out of FIT-FIP systems. | The two systems have distorted electricity prices [37,86], overlooked electricity demand [37,65], damaged energy innovation [86], and created burden and uncertainty for energy consumers. |

| As market uncertainty always exists, from a free-market environmental perspective, it is still necessary to establish a market-based institution to hedge against the impact of market price fluctuations on the energy industry. | Lesser and Su [86] proposed the following four measurements for confronting price fluctuations: (1) use proven market mechanisms to elicit truthful information, (2) ensure installation efficiency and generation efficiency both in the short term and in the long term, (3) guarantee the timely achievement of policy goals, and (4) be easy to implement and monitor. Langniß et al. [65] introduced three pro-market models that might be constrictive for the energy transition: Retailer Model, Bonus Model, and Optional Bonus Model. |

| Taxation, state subsidies on energy and RE production, and state industrial access restrictions should all be eliminated as much as possible. | The hidden tax has been a component of why Spain’s electricity prices are relatively high among 28 IEA countries. As of 2022, Spain’s industrial and household electricity users must pay around 58% and 48.5% of total taxation, respectively. The Spanish government still provides energy subsidies for electrification, coal–nuclear closure, and oil products [2]. 85% of energy production, 100% of the distribution network, and 90% of final sales are controlled by four giant firms due to industrial access restrictions [32,39]. |

| Spain should also enhance its research on energy transition based on market forces, as a previous OECD study indicated. | The 2018 OECD report shows that only 3% of all capital invested in energy start-ups in Spain between 2011 and 2018 focused on digital and artificial intelligence technologies, far behind France (13%), Germany (14%), and the UK (55%) [67]. |

| Spain should conduct further free-market reform to create better energy and RE entrepreneurial innovation environment | Although the Spanish made a partial market reform under the Jose Maria Aznar government from 1996 to 2004 [102], partially liberating its electricity market, it is still ranked lower in economic freedom than other developed countries. Spain’s economic freedom score is ranked 26th among 45 countries in Europe. Its overall score is below the regional average but above the world average [103]. Spain is ranked 32nd of 180 countries in Transparency International’s 2020 Corruption Perceptions Index, but its overall score (62) is one of Western Europe’s lower scores [103]. |

| Spain should adopt proper methods to face the energy crisis caused by the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine. | The previous price inflation caused by the post-pandemic monetary expansion, the Ukrainian War, the international sanctions on Russia, and other uncertain factors make it challenging to handle the current energy transition agenda [100,105]. Unfortunately, the Spanish government continues the previous interventionist energy policy. It presented a preliminary proposal to the European Commission that established a reference price for gas of EUR 30 per megawatt (MWh) to lower the cost of electricity [106]. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, W.H.; Espinosa, V.I.; Huerta de Soto, J. A Free-Market Environmentalist Enquiry on Spain’s Energy Transition along with Its Recent Increasing Electricity Prices. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 9493. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19159493

Wang WH, Espinosa VI, Huerta de Soto J. A Free-Market Environmentalist Enquiry on Spain’s Energy Transition along with Its Recent Increasing Electricity Prices. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(15):9493. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19159493

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, William Hongsong, Victor I. Espinosa, and Jesús Huerta de Soto. 2022. "A Free-Market Environmentalist Enquiry on Spain’s Energy Transition along with Its Recent Increasing Electricity Prices" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 15: 9493. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19159493

APA StyleWang, W. H., Espinosa, V. I., & Huerta de Soto, J. (2022). A Free-Market Environmentalist Enquiry on Spain’s Energy Transition along with Its Recent Increasing Electricity Prices. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(15), 9493. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19159493