Smart Hand Sanitisers in the Workplace: A Survey of Attitudes towards an Internet of Things Technology

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Non-Pharmaceutical Interventions

1.2. Importance of Hand Hygiene

1.3. Smart Technologies

1.4. Hand Hygiene in Non-Clinical Settings

1.5. IoT

1.6. IoT Threats and Opportunities

2. Methods

- a respondent strongly agreed with over 70% of statements (including the negatively coded statement);

- respondents who stated that they had a non-managerial position strongly agreed with over 50% of statements (including the negatively coded statement), and responded to the conditional statements.

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characteristics

3.2. Issues Identified

3.3. Responses to the Statements

- Sensitive skin

- Sanitisers in a broader hand hygiene context

- Coercion

- Concerns about monitoring

3.4. Significant Associations between Sample Characteristics and Response to Statements

3.4.1. Age

- It is important for employers to have an accurate picture of how well their employees clean their hands.

- If colleagues repeatedly fail to clean hands properly, management should be able to take action to prevent them coming into contact with the rest of the workforce.

- Monitoring of hand hygiene at work... would signal management’s commitment to employee wellbeing.

- Data collected by Smart hand sanitisers can... display personalised messages to a user, based on that user’s previous hand hygiene behaviour.

- Data collected by Smart hand sanitisers can... help to identify individuals whose hand cleaning behaviour is below an acceptable level.

3.4.2. Sex

- Promoting good hand hygiene practice is as important as providing good hand hygiene resources.

- Levels of hand hygiene practised during the COVID-19 crisis should be maintained after the current programme of vaccination is completed.

3.4.3. Ethnicity and Home Country

3.4.4. Industry Sector

3.4.5. Responsibility for Hand Hygiene Equipment

- Installation of hand hygiene equipment.

- Maintenance of hand hygiene equipment.

- Health/wellbeing within your organisation.

- Strict hand hygiene regulations can disrupt work routines.

3.4.6. Managerial Level

3.4.7. Number of People Employed in Workplace before the Pandemic

- Good hand hygiene is important if my organisation is to function properly.

- My employer should be interested in developments that may improve hand hygiene.

3.4.8. Employment during COVID-19

- Monitoring of hand hygiene at work would signal management’s commitment to employee wellbeing.

- It is important for employers to have an accurate picture of how well their employees clean their hands.

4. Discussion

4.1. Risk Factors

4.2. Monitoring and Behavioural Modification

4.3. Limitations of the Sample

5. Conclusions

5.1. Data and Decisions

- There was a recognition by most respondents that smart IoT sanitisers had the potential to increase standards of hand hygiene. However, there were clear concerns about privacy. There were also concerns about the quality of data, and the extent to which monitoring data reflected HH practices.

- Management should not assume that sanitisers are the only means by which hands can be cleaned, since many people will wash with soap and water, or bring their own sanitising gel.

- Given such concerns, data should be gathered from Smart devices with a view to addressing defined needs, rather than simply because the technology makes data collection possible.

- If smart devices are deployed, then management should explain which decisions will be informed by the data they collect, and should demonstrate how those decisions will be influenced.

5.2. Perceptions of Risk

- Perceptions of risk may have contributed to older respondents’ apparent willingness to accept measures that could lead to a more prescriptive hand hygiene culture.

- The sociocultural perspectives of some respondents may have influenced how they balanced perceived risks, with the health benefits of rigorous hand hygiene practices being set against concerns about intrusive management.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Hand Cleaning at Your Workplace

- How old are you?

- Sex

- Female

- Male

- Prefer to self-describe

- Prefer not to say

- Ethnicity

- White

- Mixed or multiple ethnic groups

- Asian

- Black

- Other

- What is the primary sector of your organisation? (Select the most appropriate).

• Agriculture, plantations, other rural sectors • Mining (coal, other mining) • Basic Metal Production • Mechanical and electrical engineering • Charity/voluntary • Media, culture, graphical • Chemical industries • Oil and gas production, oil refining • Commerce • Postal and telecommunications services • Construction • Public service • Education • Shipping, ports, fisheries, inland waterways • Financial services, professional services • Textiles, clothing, leather, footwear • Food, drink, tobacco • Transport (including civil aviation, railways, road transport) • Forestry, wood, pulp and paper • Transport equipment manufacturing • Health services • Utilities (water, gas, electricity) • Hotels, tourism, catering • Other: - Does your job give you responsibility for any of the following (select all that apply)?

- Installation of hand hygiene equipment.

- Maintenance of hand hygiene equipment.

- Health/wellbeing within your organisation.

- None of the above.

- What is your level of employment? (Select one).

- Directorial

- Senior management

- Middle management

- Non-managerial

- Other

- In which country are you employed?

- How many people were employed in your workplace prior to the pandemic?(NB—if you work for a multi-site organisation, estimate the number that refers to the physical setting of the section or department in which you work.)

- <10

- 10–49

- 50–99

- 100–249

- 250–499

- 500+

- Can’t say

- Estimate the percentage of employees who, at the peak of the pandemic, were physically present in your workplace for at least part of a week.

- 0%

- 1–25%

- 26–50%

- 51–75%

- 76–100%

- Can’t say

- Estimate the percentage of employees likely to be physically present (for at least part of a week) when the current vaccination programme is completed.

- 0%

- 1–25%

- 26–50%

- 51–75%

- 76–100%

- Can’t say

- When COVID-19 restrictions were at their strictest, which of the following was true?

- I was required to attend my workplace at least once.

- I chose to attend my workplace at least once.

- I did all my work remotely.

- I was furloughed.

- I was unemployed.

SECTION 2: HAND HYGIENE - Importance of Hand HygieneOn a scale of 1–7 (where 1 = strongly DISagree, 7 = strongly agree), how do you feel about the following statements?

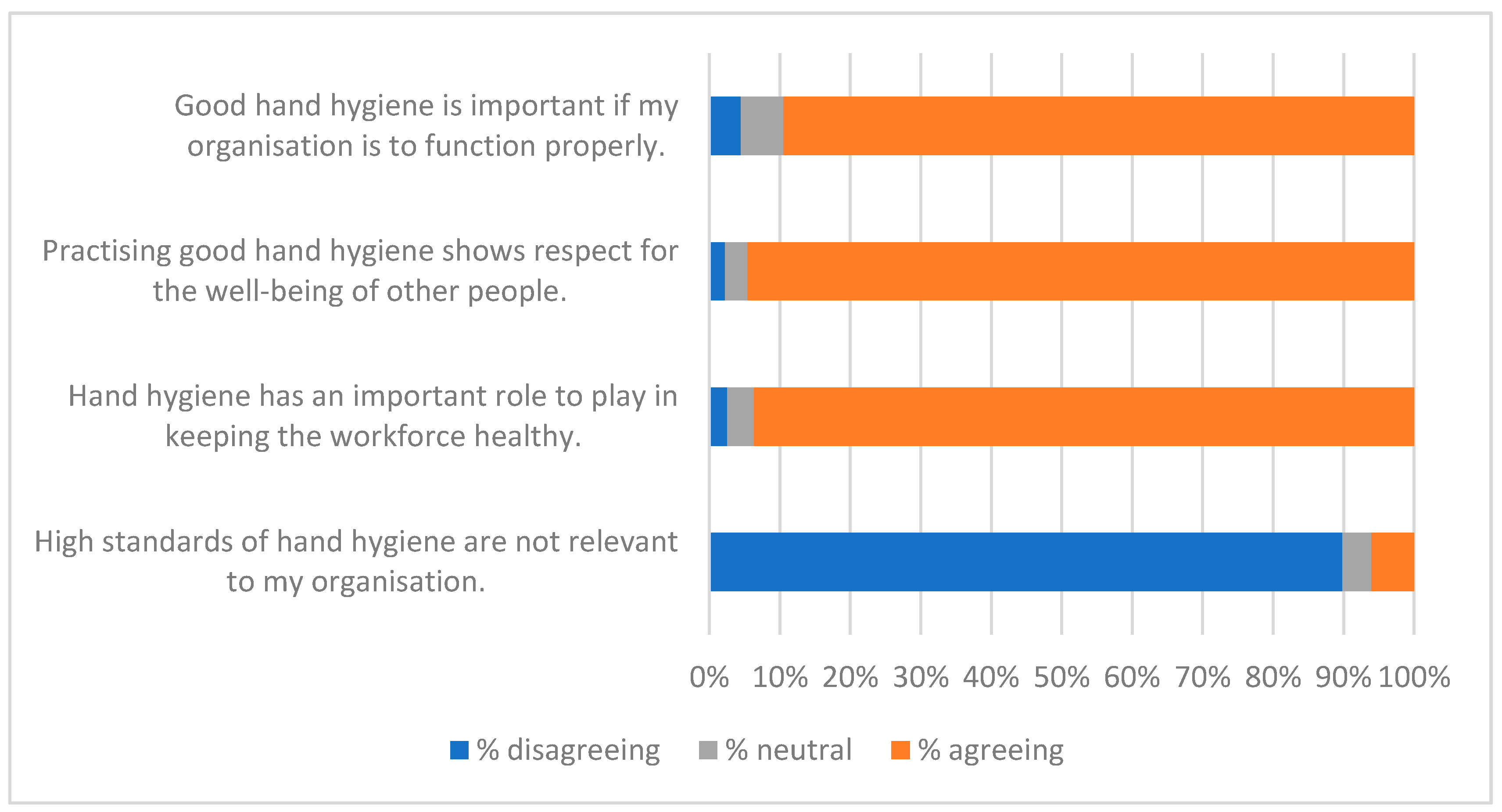

- Good hand hygiene is important if my organisation is to function properly.

- Practising good hand hygiene shows respect for the well-being of other people.

- Hand hygiene has an important role to play in keeping the workforce healthy.

- High standards of hand hygiene are not relevant to my organisation.

- Good hand hygiene is important if my organisation is to function properly.

- Practising good hand hygiene shows respect for the well-being of other people.

- Hand hygiene has an important role to play in keeping the workforce healthy.

- High standards of hand hygiene are not relevant to my organisation.

- Investing in Hand HygieneOn a scale of 1–7 (where 1 = strongly DISagree, 7 = strongly agree), how do you feel about the following statements?

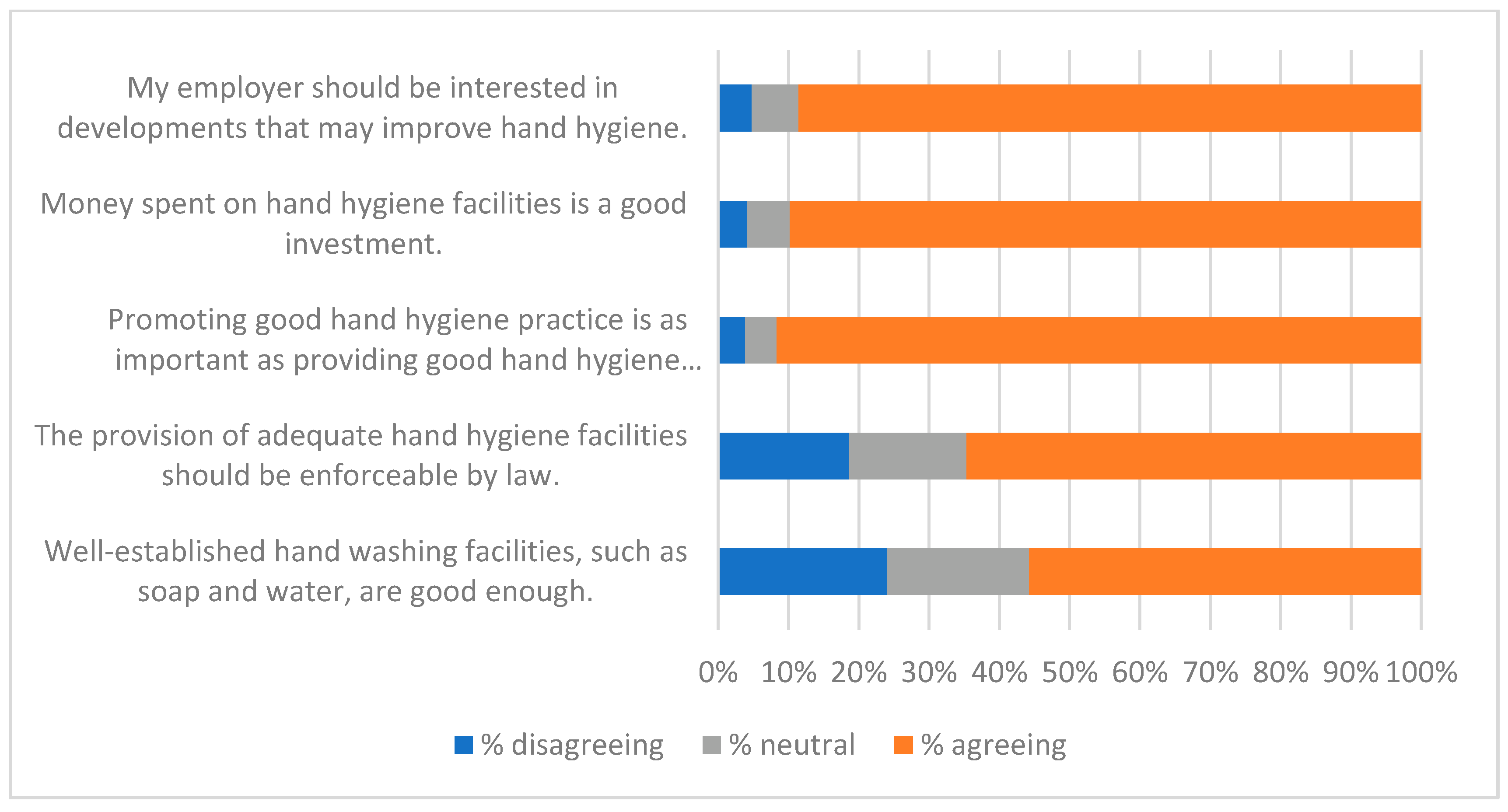

- My employer should be interested in developments that may improve hand hygiene.

- Money spent on hand hygiene facilities is a good investment.

- Promoting good hand hygiene practice is as important as providing good hand hygiene resources.

- The provision of adequate hand hygiene facilities should be enforceable by law.

- Well-established hand washing facilities, such as soap and water, are good enough.

- Promoting Hand HygieneOn a scale of 1–7 (where 1 = strongly DISagree, 7 = strongly agree), how do you feel about the following statements?

- Employees should be given clear guidance on good practice for hand hygiene.

- It is important for employers to have an accurate picture of how well their employees clean their hands.

- Good hand hygiene is a personal matter, so employers should not interfere.

- An organisation should ensure that its employees maintain a minimum standard of hand hygiene.

- Strict hand hygiene regulations can disrupt work routines.

SECTION 3: IMPACT OF COVID-19 - Impact of COVID-19 on Hand HygieneOn a scale of 1–7 (where 1 = strongly DISagree, 7 = strongly agree), how do you feel about the following statements?

- COVID-19 has made me more aware of the importance of good hand hygiene as a public health measure.

- If colleagues repeatedly fail to clean their hands properly, management should be able to take action to prevent them coming into contact with the rest of the workforce.

- Levels of hand hygiene practised during the COVID-19 crisis should be maintained after the current programme of vaccination is completed.

- As a result of COVID-19, my employer should be prepared to introduce measures that ensure compliance with handwashing guidelines.

- Spread of COVID-19On a scale of 1–7 (where 1 = Totally UNconcerned, 7 = Extremely concerned), how do you feel about the following statements?

- I may contract COVID from colleagues.

- I may contract COVID from people I meet in the course of work, but who are not employed by my organisation.

- I may spread COVID to colleagues.

- I may spread COVID to non-colleagues I meet in the course of work.

- Management perspective(Only complete the remainder of this section if you have managerial responsibility).On a scale of 1–7 (where 1 = Totally UNconcerned, 7 = Extremely concerned), how do you feel about the following statements?

- Employees may contract COVID from colleagues.

- Employees may contract COVID from people they meet in the course of work, but who are not employed by my organisation.

SECTION 4: MONITORING HAND HYGIENEAcceptance of MonitoringSmart hand sanitisers are able to collect data about when and where they are used, and about who uses them - On a scale of 1–7 (where 1 = very UNhappy, 7 = very happy), how do you feel about the following statements?Data collected by Smart hand sanitisers can...

- ...provide maintenance staff with up-to-date information about whether or not sanitisers are working properly.

- ... give me an overview of my own hand hygiene practice.

- ... give an anonymised overview that enables me to compare hand hygiene practice across different parts of my organisation.

- ... give managers an anonymised overview of hand hygiene practice within the organisation.

- ... display personalised messages to a user, based on that user’s previous hand hygiene behaviour.

- ... help to identify individuals whose hand cleaning behaviour is below an acceptable level.

Perceptions of monitoring hand hygiene - On a scale of 1–7 (where 1 = strongly DISagree, 7 = strongly agree), how do you feel about the following statements?Monitoring of hand hygiene at work...

- ...would signal management’s commitment to employee wellbeing.

- ...is an unjustifiable invasion of privacy.

- ...would help me to feel safer because colleagues whose hands were not cleaned could be identified.

- ...would provide accurate data that would improve decisions relating to hand hygiene.

- We are looking for people who are willing to help further with this project (for example, with interviews or focus groups). If you would like to volunteer, please give an email address in the box below.

- If you have any observations or suggestions regarding the topics covered by this questionnaire, please feel free to comment below.

Appendix B. Qualitative Questionnaire

- If you have experience or expertise that you feel is particularly relevant, please describe it below

- If you would like to discuss the matters explored in this questionnaire rather than (or in addition to) providing written answers, tick the box below and we will arrange an online interview.

- How important is hand hygiene in your organisation?

- How is this level of importance reflected in management policy?

- What role do hand sanitisers play within your organisation?

- What impact has COVID 19 had on your organisation’s approach to hand hygiene?

- At your organisation, are there aspects of behaviour relating to hygiene that could be improved?

- What changes could lead to such behaviour be adopted?

- Could such data be beneficial to your organisation?

- Could it help your organisation with decisions other than those listed above?

- Which (if any of these) are you concerned about? What are the reasons for your concerns?

- Are there any further reasons why monitoring of hand cleaning may create concerns for your organisation?

- Are there cultural factors that might influence the way IoT hand sanitisers could be used in your organisation or your society? If so, what are they?

- Are there cultural factors that might influence the way monitoring of behaviour is viewed in your organisation or your society? If so, what are they?

- How would you rate the quality of the information and advice your organisation provided relating to hand hygiene?

- Were there gaps that you had to fill yourself? Where did you find the information you needed?

- What further information or advice would benefit your organisation?

- Feel free to make further comments on the subject of Hand Cleaning at your Workplace

References

- Dai, T.; Tayur, S. Om forum—Healthcare operations management: A snapshot of emerging research. Manuf. Serv. Oper. Manag. 2019, 22, 869–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mullard, A. COVID-19 vaccine development pipeline gears up. Lancet 2020, 395, 1751–1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, J.; Patón, M.; Acuña, J.M. COVID-19 vaccination rate and protection attitudes can determine the best prioritisation strategy to reduce fatalities. medRxiv 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Z.; Jun Wen, J.; Abbas, J.; McDonnell, D.; Cheshmehzangi, A.; Xiaoshan Li, X.; Ahmad, J.; Šegalo, S.; Maestro, D.; Cai, Y. A race for a better understanding of COVID-19 vaccine non-adopters. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020, 9, 100159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galdston, I. Health education and the public health of the future. J. Educ. Sociol. 1929, 2, 341–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HSE. Workplace (Health, Safety and Welfare) Regulations 1992; The Stationery Office: London, UK, 1992; pp. 1–60. [Google Scholar]

- Stones, C.; Ai, W.; Rutter, S.; Madden, A.D. Developing novel visual messages for a video screen hand sanitizer: A co-design study with students. Des. Health 2022, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CDC. Hand Hygiene at Work. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/handwashing/handwashing-corporate.html (accessed on 28 July 2022).

- Lawson, A.; Vaganay-Miller, M.; Cameron, R. An Investigation of the general population’s self-reported hand hygiene behaviour and compliance in a cross-european setting. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitby, M.; Pessoa-Silva, C.L.; McLaws, M.L.; Allegranzi, B.; Sax, H.; Larson, E.; Seto, W.H.; Donaldson, L.; Pittet, D. Behavioural considerations for hand hygiene practices: The basic building blocks. J. Hosp. Infect. 2007, 65, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutter, S.; Macduff, C.; Stones, C.; Gomez-Escalada, M. Evaluating children’s handwashing in schools: An integrative review of indicative measures and measurement tools. Int. J. Environ. Health Res. 2021, 31, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. A Guide to the Implementation of the Who Multimodal Hand Hygiene Improvement Strategy; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Erasmus, V.; Daha, T.J.; Brug, H.; Richardus, J.H.; Behrendt, M.D.; Vos, M.C.; van Beeck, E.F. Systematic review of studies on compliance with hand hygiene guidelines in hospital care. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2010, 31, 283–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gluyas, H. Understanding non-compliance with hand hygiene practices. Nurs. Stand. 2015, 29, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cumbler, E.; Castillo, L.; Satorie, L.; Ford, D.; Hagman, J.; Hodge, T.; Price, L.; Wald, H. Culture change in infection control: Applying psychological principles to improve hand hygiene. J. Nurs. Care Qual. 2013, 28, 304–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cawthorne, K.R.; Cooke, R.P.D. Healthcare workers’ attitudes to how hand hygiene performance is currently Monitored and assessed. J. Hosp. Infect. 2020, 105, 705–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goddard, N.D.R.; Kemp, R.M.J.; Lane, R. An overview of smart technology. Packag. Technol. Sci. Int. J. 1997, 10, 129–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swoboda, S.M.; Earsing, K.; Strauss, K.; Lane, S.; Lipsett, P.A. Electronic monitoring and voice prompts improve hand hygiene and decrease nosocomial infections in an intermediate care unit*. Crit. Care Med. 2004, 32, 358–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, D.A.; TSeetoh, A.T.; Oh May-Lin, H.; Viswanathan, S.; Toh, Y.; Yin, W.C.; Eng, L.S.; Yang, T.S.; Schiefen, S.; Dempsey, M.; et al. Automated measures of hand hygiene compliance among healthcare workers using ultrasound: Validation and a randomized controlled trial. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2013, 34, 919–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaube, S.; Fischer, P.; Windl, V.; Lermer, E. The effect of persuasive messages on hospital visitors’ hand hygiene behavior. Health Psychol. 2020, 39, 471–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Xu, N.; Liu, C.; Feng, Y.; Li, F.; Meng, X.; Lv, Q.; Lan, C. Influence of the internet of things management system on hand hygiene compliance in an emergency intensive care unit. J. Hosp. Infect. 2021, 109, 101–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nosowitz, D. The Surprising—and Surprisingly Contentious—History of Purell. Vanity Fair 2020. Available online: https://www.vanityfair.com/style/2020/03/purell-hand-sanitizer-history (accessed on 2 August 2022).

- Edmond, M.B.; Goodell, A.; Zuelzer, W.; Sanogo, K.; Elam, K.; Bearman, G. Successful use of alcohol sensor technology to monitor and report hand hygiene compliance. J. Hosp. Infect. 2010, 76, 364–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Jiang, W.; Yang, K.; Yu, D.; Newn, J.; Sarsenbayeva, Z.; Goncalves, J.; Kostakos, V. Electronic monitoring systems for hand hygiene: Systematic review of technology. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 23, e27880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, E.; Vanick, K. A survey of hand hygiene practices on a residential college campus. Am. J. Infect. Control 2007, 35, 694–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haston, J.C.; Miller, G.F.; Berendes, D.; Andújar, A.; Marshall, B.; Cope, J.; Hunter, C.M.; Robinson, B.M.; Hill, V.R.; Garcia-Williams, A.G. Characteristics associated with adults remembering to wash hands in multiple situations before and during the COVID-19 pandemic—United States, October 2019 and June 2020. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2020, 69, 1443–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O'Boyle, C.A.; Henly, S.J.; Larson, E. Understanding adherence to hand hygiene recommendations: The theory of planned behavior. Am. J. Infect. Control 2001, 29, 352–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbogast, J.W.; Moore-Schiltz, L.; Jarvis, W.R.; Harpster-Hagen, A.; Hughes, J.; Parker, A. Impact of a comprehensive workplace hand hygiene program on employer health care insurance claims and costs, absenteeism, and employee perceptions and practices. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2016, 58, e231–e240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zivich, P.N.; Gancz, A.S.; Aiello, A.E. Effect of hand hygiene on infectious diseases in the office workplace: A systematic review. Am. J. Infect. Control 2018, 46, 448–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judge, L.; Slaughter, H. Failed Safe?: Enforcing Workplace Health and Safety in the Age of COVID-19; Resolution Foundation: London, UK, 2020; Available online: https://www.resolutionfoundation.org/publications/failed-safe/ (accessed on 2 August 2022).

- Leiner, B.M.; Cerf, V.G.; Clark, D.D.; Kahn, R.E.; Kleinrock, L.; Lynch, D.C.; Postel, J.; Roberts, L.G.; Wolff, S. A brief history of the internet. SIGCOMM Comput. Commun. Rev. 2009, 39, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashton, K. That ‘Internet of Things’ thing. RFID J. 2009. Available online: https://www.rfidjournal.com/that-internet-of-things-thing (accessed on 2 August 2022).

- Porambage, P.M.; Ylianttila, C.; Schmitt, P.; Kumar, A.; Gurtov, A.; Vasilakos, A.V. The quest for privacy in the internet of things. IEEE Cloud Comput. 2016, 3, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scammell, R.; Hyppönen, M. Smart devices are “It Asbestos”. Verdict 2019. Available online: https://www.verdict.co.uk/mikko-hypponen-smart-devices-it-asbestos/ (accessed on 2 August 2022).

- Mukhtar, H.; Rubaiee, S.; Krichen, M.; Alroobaea, R. An IoT framework for screening of COVID-19 using real-time data from wearable sensors. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, F.; Wu, T.; Zarate, D.C.; Morfuni, R.; Kerley, B.; Hinds, J.; Taniar, D.; Armstrong, M.; Yuce, M.R. An autonomous hand hygiene tracking sensor system for prevention of hospital associated infections. IEEE Sens. J. 2021, 21, 14308–14319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Zhou, B.; Butler, J.P.; Bock, R.G.; Portelli, J.P.; Bilén, S.G. IoT-based sanitizer station network: A facilities management case study on monitoring hand sanitizer dispenser usage. Smart Cities 2021, 4, 979–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbert, J.; Horsham, C.; Ford, H.; Wall, A.; Hacker, E. Deployment of a smart handwashing station in a school setting during the COVID-19 pandemic: Field study. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2020, 6, e22305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bal, M.; Abrishambaf, R. A system for monitoring hand hygiene compliance based-on internet-of-things. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Industrial Technology (ICIT), Toronto, ON, Canada, 22–25 March 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Peirce, C. Deduction, induction, and hypothesis. In Illustrations of the Logic. of Science; de Waal C, Ed.; Open Court: Chicago, IL, USA, 2014; pp. 167–184. [Google Scholar]

- HRA. COVID-19–Workplace Risk Assessment All Offices. NHS. Available online: https://www.hra.nhs.uk/about-us/governance/covid-19-workplace-risk-assessment-all-offices/ (accessed on 9 May 2022).

- Jager, J.; Putnick, D.L.; Bornstein, M.H., II. more than just convenient: The scientific merits of homogeneous convenience samples. Monogr. Soc. Res. Child. Dev. 2017, 82, 13–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Henry, G. Sample selection approaches. In Practical Sampling; Henry, G., Ed.; Sage: London, UK, 1990; pp. 17–22. [Google Scholar]

- Preston, C.C.; Colman, A.M. Optimal number of response categories in rating scales: Reliability, validity, discriminating power, and respondent preferences. Acta. Psychol. 2000, 104, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Neyman, J.; Pearson, E.S. The testing of statistical hypotheses in relation to probabilities a priori. Math. Proc. Camb. Philos. Soc. 1933, 29, 492–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyatzis, R.E. Developing themes and codes. In Transforming Qualitative Information: Thematic Analysis and Code Development; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1988; pp. 29–53. [Google Scholar]

- Malhotra, M.K. Data preparation. In Marketing Research: An. Applied Orientation; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bower, K.M. When to Use Fisher’s Exact Test. In American Society for Quality. Six Sigma Forum Mag. 2003, 2, 35–37. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, G.; Volgman, A.S.; Michos, E.D. Sex differences in mortality from COVID-19 pandemic: Are men vulnerable and women protected? JACC Case Rep. 2020, 2, 1407–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiegelhalter, D. Use of “Normal” Risk to Improve Understanding of Dangers of COVID-19. BMJ 2020, 370, m3259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolff, D.; Nee, S.; Hickey, N.S.; Marschollek, M. Risk factors for COVID-19 severity and fatality: A structured literature review. Infection 2021, 49, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, C.; Nguyen, L.H.; Drew, D.A.; Warner, E.T.; Joshi, A.D.; Graham, M.S.; Anyane-Yeboa, A.; Shebl, F.M.; Astley, C.M.; Figueiredo, J.C.; et al. Race, Ethnicity, Community-Level Socioeconomic Factors, and Risk of COVID-19 in the United States and the United Kingdom. EClinicalMedicine 2021, 38, 101029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, H.D.; Sholcosky, D.; Gabello, K.; Ragni, R.; Ogonosky, N. Sex differences in public restroom handwashing behavior associated with visual behavior prompts. Percept. Mot. Ski. 2003, 97, 805–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, M. Epistemic divides and ontological confusions: The psychology of vaccine scepticism. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2018, 14, 2540–2542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Madden, A.D. A review of basic research tools without the confusing philosophy. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 2022, 41, 1633–1647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Age | 21–25 | 26–30 | 31–35 | 36–40 | 41–45 | 46–50 | 51–55 | 56–60 | 61–65 | 66+ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | 2.6 | 7.2 | 8.2 | 14.1 | 16.0 | 11.4 | 17.6 | 13.4 | 7.5 | 2.0 |

| Management Level | Non-Managerial | Middle Management | Senior Management | Directorial |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | 53.1 | 33.4 | 9.0 | 4.5 |

| Industry Sector | % |

|---|---|

| Charity/voluntary | 10.2 |

| Education | 43.3 |

| Financial and professional services | 3.5 |

| Health services | 5.4 |

| Heritage | 2.2 |

| Media, culture, graphical | 4.1 |

| Public service | 20.7 |

| Transport | 2.5 |

| Other | 8 |

| Size of Workforce | <10 | 10–49 | 50–99 | 100–249 | 500+ | Don’t Know |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | 8.9 | 19.7 | 5.1 | 18.5 | 43.0 | 4.8 |

| 0% | 1–25% | 26–50% | 51–75% | 76–100% | Can’t Say | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimated attendance at peak lockdown (% responses) | 16.6 | 50.3 | 6.1 | 4.5 | 12.1 | 10.5 |

| Estimated attendance after vaccination programme (% responses) | 0.6 | 12.1 | 16.2 | 19.4 | 38.2 | 13.4 |

| Status | Unemployed | Furloughed | Worked Remotely | Chose to Attend Work | Required to Attend Work |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | 2.2 | 6.1 | 64.2 | 12.5 | 15.0 |

| <0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | Can’t Say |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5.7 | 16.9 | 19.7 | 17.5 | 20.4 | 5.4 | 20.1 |

| Behavioural change | “…historical data in the UK shows that improving public awareness rather than legally enforcing some behaviours, is the long term route to improving take up.” “Good/best practice needs to come from the top down and if senior managers aren’t seen to be doing something those at the lower levels won’t do it either.” |

| Circumstances where monitoring is acceptable | “I think it’s a good idea to be able to monitor use and performance of hand sanitising stations, but not to be able to identify individuals.” “Certainly it would help our organisation stay on top of re-filling the devices, as sometimes our current devices run out of sanitiser. It could also help demonstrate when staff are and aren’t cleaning their hands at appropriate moments, for example when entering the cafeteria or when entering the building.” |

| Coercion | “…we are managed by a group of people who believe in divide and rule and who manage people through criticism and humiliation. To give these people a data set which they will simply use as a stick to beat different work units in the organisation is very foolish.” “…collecting data that leads to behavioral impositions would not be welcomed” |

| Cultural perspective | “Many parts of the USA have a more libertarian approach to everything, but especially things considered very personal and private such as hygiene and surveillance. The consideration in such culture is that courtesy and respect should not be coerced or monitored. Personal responsibility does not extend to interfering in someone else’s life.” “My answers are coloured by the fact that I work in a hospital so hand hygiene is already of critical importance.” |

| Data quality | “Hand sanitisers provide fundamentally unsafe data... by exclusively following sanitiser data, rather than sink data, you’re not really helping change public health education.” “People may choose to use their own hand sanitisers, or to wash their hands with soap and water instead, so the smart sanitisers may not collect an accurate picture of who is sanitising their hands and when.” |

| Data use | “…if you’re going to be collecting it [data] then you need to be actioning something on the back of it.” “Why would I collect that data? It’s difficult for me to visualise sitting in front of that data and doing anything with it.” |

| Impact of COVID-19 | “[COVID] has given hand hygiene a much, much higher profile than it had before in the general organisation. In the laboratories there was already a very strict insistence on hand hygiene. However in most areas—offices, stores, teaching areas—there was very limited emphasis on it…” “Sanitiser was never previously provided, however hand hygiene was always important as extensive hand washing facilities have always been provided” |

| Personal preference | “Sanitising liquid is horrible…” “…I don’t like hand sanitisers and after using them I prefer to wash my hands as soon as possible.” |

| Privacy concerns | “…singling out individuals makes me feel uncomfortable and I feel is an invasion of privacy and in a workplace there should be two-way trust and respect, and feeling spied upon by your employer does not play any part in that.” “It’s a difficult balance between big brother and the welfare of colleagues and customers and… I do not think it would be an easy sell to my teams” |

| Sanitisers in broader HH context | “COVID-19 is a respiratory virus and the biggest risks are from not covering the nose and mouth, or close contact with potentially infected people. Focusing on only hand hygiene is missing a major contributor to the spread of this respiratory virus.” “The survey appears slightly biased towards ‘sanitisation’, which suggests the use of a sanitiser, whereas guidance suggests that soap and water is better when available.” |

| Sensitive skin | “The importance of hand hygiene in disease spread needs to be balanced against the wellbeing of employees with skin conditions such as eczema which may be exacerbated” “Hand washing is better than sanitising, which has given me dermatitis in the past.” |

| Unintended consequences | “...making it solely the responsibility of the individual by ‘invading privacy’ will create a back lash and is an easy target for misinformation on social media.” “I think it could easily be used as a stick rather than a carrot by poor managers so I could see that being more toxic than passing on germs in some workplaces!” |

| Workplace context | “In the course of their work some people remove our refuse and clean our public buildings, some handle cash, some operate machinery and some build our homes and infrastructure. It would be wrong to monitor people all the time and expect them to have hands as clean as a surgeon.” “[Company name] manufactures food and pharmaceutical labels/packaging… Comparing a conventional print manufacturing site without hygiene standards to one with our level could skew any results were that not taken into consideration.” |

| % Dis-Agree | % Neutral | % Agree | N | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Good hand hygiene is important if my organisation is to function properly. | Younger | 6.5 | 7.8 | 85.6 | 153 |

| Older | 2.6 | 4.6 | 92.8 | 153 | |

| My employer should be interested in developments that may improve hand hygiene. | Younger | 5.2 | 9.8 | 85.0 | 153 |

| Older | 4.6 | 3.3 | 92.2 | 153 | |

| Money spent on hand hygiene facilities is a good investment | Younger | 4.6 | 7.8 | 87.6 | 153 |

| Older | 3.9 | 3.9 | 92.2 | 153 | |

| Promoting good hand hygiene practice is as important as providing good hand hygiene resources | Younger | 5.3 | 6.6 | 88.2 | 152 |

| Older | 2.6 | 2.6 | 94.8 | 153 | |

| Employees should be given clear guidance on good practice for hand hygiene | Younger | 5.2 | 10.5 | 84.3 | 153 |

| Older | 3.9 | 6.5 | 89.5 | 153 | |

| It is important for employers to have an accurate picture of how well their employees clean their hands | Younger | 32.7 | 22.9 | 44.4 | 153 |

| Older | 19.6 | 20.9 | 59.5 | 153 | |

| An organisation should ensure that its employees maintain a minimum standard of hand hygiene | Younger | 22.2 | 23.5 | 54.2 | 153 |

| Older | 13.9 | 15.9 | 70.2 | 151 | |

| If colleagues repeatedly fail to clean hands properly, management should be able to take action to prevent them coming into contact with the rest of the workforce | Younger | 42.2 | 23.4 | 34.4 | 153 |

| Older | 31.6 | 17.1 | 51.3 | 152 | |

| As a result of COVID-19, my employer should be prepared to introduce measures that ensure compliance with handwashing guidelines | Younger | 29.4 | 20.3 | 50.3 | 153 |

| Older | 21.6 | 9.2 | 69.3 | 153 | |

| ... give me an overview of my own hand hygiene practice | Younger | 22.4 | 22.4 | 55.3 | 152 |

| Older | 17.4 | 14.8 | 67.8 | 149 | |

| ... give an anonymised overview that enables me to compare hand hygiene practice across different parts of my organisation | Younger | 27.8 | 21.2 | 51.0 | 151 |

| Older | 17.6 | 16.2 | 66.2 | 148 | |

| ... give managers an anonymised overview of hand hygiene practice within the organisation | Younger | 25.7 | 21.1 | 53.3 | 152 |

| Older | 16.8 | 16.8 | 66.4 | 149 | |

| ... display personalised messages to a user, based on that user’s previous hand hygiene behaviour | Younger | 50.7 | 11.2 | 38.2 | 152 |

| Older | 36.9 | 16.1 | 47.0 | 149 | |

| ... help to identify individuals whose hand cleaning behaviour is below an acceptable level | Younger | 57.2 | 13.8 | 28.9 | 152 |

| Older | 40.9 | 17.4 | 41.6 | 149 | |

| ... would signal management’s commitment to employee wellbeing | Younger | 34.6 | 21.6 | 43.8 | 153 |

| Older | 24.8 | 14.1 | 61.1 | 149 | |

| ... would help me to feel safer because colleagues whose hands were not cleaned could be identified | Younger | 48.7 | 17.1 | 34.2 | 152 |

| Older | 35.6 | 16.1 | 48.3 | 149 |

| Good hand hygiene is a personal matter, so employers should not interfere. | Younger | 59.5 | 22.2 | 18.3 | 153 |

| Older | 62.7 | 15.7 | 21.6 | 153 | |

| Strict hand hygiene regulations can disrupt work routines.] | Younger | 69.1 | 11.2 | 19.7 | 152 |

| Older | 76.5 | 11.8 | 11.8 | 153 |

| Corresponding Figure | % Difference | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Figure 4 | 1 | As a result of COVID-19, my employer should be prepared to introduce measures that ensure compliance with handwashing guidelines | 19.0 |

| Figure 7 | 2 | ... would signal management’s commitment to employee wellbeing | 17.3 |

| Figure 4 | 3 | If colleagues repeatedly fail to clean their hands properly, management should be able to take action to prevent them coming into contact with the rest of the workforce | 16.9 |

| Figure 3 | 4 | An organisation should ensure that its employees maintain a minimum standard of hand hygiene | 16.0 |

| Figure 6 | 5 | ... give an anonymised overview that enables me to compare hand hygiene practice across different parts of my organisation | 15.2 |

| Figure 3 | 6 | It is important for employers to have an accurate picture of how well their employees clean their hands | 15.0 |

| Figure 7 | 7 | ... would help me to feel safer because colleagues whose hands were not cleaned could be identified | 14.1 |

| Figure 6 | 8 | ... give managers an anonymised overview of hand hygiene practice within the organisation | 13.2 |

| Figure 7 | 9 | ... help to identify individuals whose hand cleaning behaviour is below an acceptable level | 12.7 |

| Figure 6 | 10 | ... give me an overview of my own hand hygiene practice | 12.5 |

| Figure 6 | 11 | ... display personalised messages to a user, based on that user’s previous hand hygiene behaviour | 8.8 |

| Figure 3 | 12 | Strict hand hygiene regulations can disrupt work routines. | −8.0 |

| Figure 1 | 13 | Good hand hygiene is important if my organisation is to function properly. | 7.2 |

| Figure 2 | 14 | My employer should be interested in developments that may improve hand hygiene. | 7.2 |

| Figure 2 | 15 | Promoting good hand hygiene practice is as important as providing good hand hygiene resources | 6.6 |

| Figure 3 | 16 | Employees should be given clear guidance on good practice for hand hygiene | 5.2 |

| Figure 2 | 17 | Money spent on hand hygiene facilities is a good investment | 4.6 |

| Figure 3 | 18 | Good hand hygiene is a personal matter, so employers should not interfere. | 3.3 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Madden, A.D.; Rutter, S.; Stones, C.; Ai, W. Smart Hand Sanitisers in the Workplace: A Survey of Attitudes towards an Internet of Things Technology. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 9531. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19159531

Madden AD, Rutter S, Stones C, Ai W. Smart Hand Sanitisers in the Workplace: A Survey of Attitudes towards an Internet of Things Technology. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(15):9531. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19159531

Chicago/Turabian StyleMadden, Andrew D., Sophie Rutter, Catherine Stones, and Wenbo Ai. 2022. "Smart Hand Sanitisers in the Workplace: A Survey of Attitudes towards an Internet of Things Technology" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 15: 9531. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19159531

APA StyleMadden, A. D., Rutter, S., Stones, C., & Ai, W. (2022). Smart Hand Sanitisers in the Workplace: A Survey of Attitudes towards an Internet of Things Technology. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(15), 9531. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19159531