Total Pain and Illness Acceptance in Pelvic Cancer Patients: Exploring Self-Efficacy and Stress in a Moderated Mediation Model

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Total Pain and Illness Acceptance

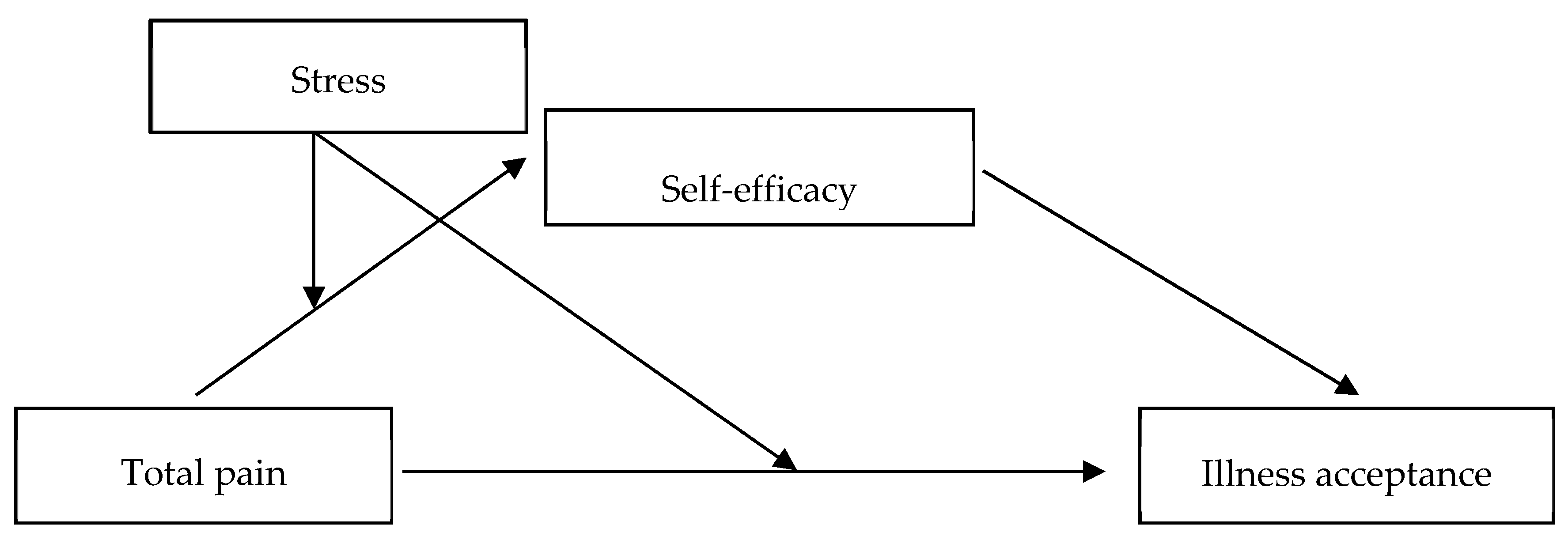

1.2. The Mediating and Moderating Roles of Self-Efficacy and Stress

1.3. The Present Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Power Analysis

2.2. Participants and Recruitment Procedure

2.3. Measures

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Correlational Analysis

3.2. Mediation Analysis

3.3. Moderated Mediation Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. The Relationship between Total Pain and Illness Acceptance

4.2. The Mediating Roles of Self-Efficacy

4.3. The Moderated Mediation Effects of Stress and Self-Efficacy

4.4. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fischer, D.J.; Villines, D.; Kim, Y.O.; Epstein, J.B.; Wilkie, D.J. Anxiety, Depression, and Pain: Differences by Primary Cancer. Support. Care Cancer 2010, 18, 801–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mishra, S.; Bhatnagar, S.; Rana, S.P.; Khurana, D.; Thulkar, S. Efficacy of the Anterior Ultrasound-Guided Superior Hypogastric Plexus Neurolysis in Pelvic Cancer Pain in Advanced Gynecological Cancer Patients. Pain Med. 2013, 14, 837–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hossain, M.A.; Asamoah-Boaheng, M.; Badejo, O.A.; Bell, L.V.; Buckley, N.; Busse, J.W.; Campbell, T.S.; Corace, K.; Cooper, L.K.; Flusk, D. Prescriber Adherence to Guidelines for Chronic Noncancer Pain Management with Opioids: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Health Psychol. 2020, 39, 430–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, X.; Ou, M.; Xie, C.; Cheng, Q.; Chen, Y. Pain Acceptance and Its Associated Factors among Cancer Patients in Mainland China: A Cross-Sectional Study. Pain Res. Manag. 2019, 2019, 9458683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polański, J.; Chabowski, M.; Jankowska-Polańska, B.; Janczak, D.; Rosińczuk, J. Histological Subtype of Lung Cancer Affects Acceptance of Illness, Severity of Pain, and Quality of Life. J. Pain Res. 2018, 11, 727–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gauthier, L.R.; Rodin, G.; Zimmermann, C.; Warr, D.; Moore, M.; Shepherd, F.; Gagliese, L. Acceptance of Pain: A Study in Patients with Advanced Cancer. Pain 2009, 143, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, L.F.; Kroenke, K.; Theobald, D.E.; Wu, J.; Tu, W. The Association of Depression and Anxiety with Health-Related Quality of Life in Cancer Patients with Depression and/or Pain. Psycho-Oncology 2010, 19, 734–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Saunders, C. The Symptomatic Treatment of Incurable Malignant Disease. Prescr. J. 1964, 4, 68–73. [Google Scholar]

- Saunders, D.C.M. The Management of Terminal Illness; Hospital Medicine Publications: London, UK, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Mehta, A.; Chan, L.S. Understanding of the Concept of “Total Pain”: A Prerequisite for Pain Control. J. Hosp. Palliat. Nurs. 2008, 10, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myrcik, D.; Statowski, W.; Trzepizur, M.; Paladini, A.; Corli, O.; Varrassi, G. Influence of Physical Activity on Pain, Depression and Quality of Life of Patients in Palliative Care: A Proof-of-Concept Study. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner-Cobb, J.M.; Michalaki, M.; Osborn, M. Self-Conscious Emotions in Patients Suffering from Chronic Musculoskeletal Pain: A Brief Report. Psychol. Health 2015, 30, 495–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raja, S.N.; Carr, D.B.; Cohen, M.; Finnerup, N.B.; Flor, H.; Gibson, S.; Keefe, F.; Mogil, J.S.; Ringkamp, M.; Sluka, K.A.; et al. The revised IASP definition of pain: Concepts, challenges, and compromises. Pain 2020, 161, 1976–1982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, J.W.; Wong, T.K.; Yang, J.C. The Lens Model: Assessment of Cancer Pain in a Chinese Context. Cancer Nurs. 2000, 23, 454–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luszczynska, A.; Benight, C.C.; Cieslak, R. Self-Efficacy and Health-Related Outcomes of Collective Trauma: A Systematic Review. Eur. Psychol. 2009, 14, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Calderon, J.; Meeus, M.; Struyf, F.; Luque-Suarez, A. The Role of Self-Efficacy in Pain Intensity, Function, Psychological Factors, Health Behaviors, and Quality of Life in People with Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Systematic Review. Physiother. Theory Pract. 2020, 36, 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirai, K.; Suzuki, Y.; Tsuneto, S.; Ikenaga, M.; Hosaka, T.; Kashiwagi, T. A Structural Model of the Relationships among Self-Efficacy, Psychological Adjustment, and Physical Condition in Japanese Advanced Cancer Patients. Psycho-Oncol. J. Psychol. Soc. Behav. Dimens. Cancer 2002, 11, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haas, B.K. Fatigue, Self-Efficacy, Physical Activity, and Quality of Life in Women with Breast Cancer. Cancer Nurs. 2011, 34, 322–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omran, S.; Mcmillan, S. Symptom Severity, Anxiety, Depression, Self-Efficacy and Quality of Life in Patients with Cancer. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. APJCP 2018, 19, 365–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikkelsen, H.T.; Haraldstad, K.; Helseth, S.; Skarstein, S.; Småstuen, M.C.; Rohde, G. Pain and Health-Related Quality of Life in Adolescents and the Mediating Role of Self-Esteem and Self-Efficacy: A Cross-Sectional Study Including Adolescents and Parents. BMC Psychol. 2021, 9, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syrjala, K.L.; Jensen, M.P.; Mendoza, M.E.; Jean, C.Y.; Fisher, H.M.; Keefe, F.J. Psychological and Behavioral Approaches to Cancer Pain Management. J. Clin. Oncol. 2014, 32, 1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Curtis, R.; Groarke, A.; Sullivan, F. Stress and Self-Efficacy Predict Psychological Adjustment at Diagnosis of Prostate Cancer. Sci. Rep. 2014, 4, 5569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Aldridge, A.A.; Roesch, S.C. Coping and Adjustment in Children with Cancer: A Meta-Analytic Study. J. Behav. Med. 2007, 30, 115–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manigault, A.W.; Ganz, P.A.; Irwin, M.R.; Cole, S.W.; Kuhlman, K.R.; Bower, J.E. Moderators of Inflammation-Related Depression: A Prospective Study of Breast Cancer Survivors. Transl. Psychiatry 2021, 11, 615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Secinti, E.; Tometich, D.B.; Johns, S.A.; Mosher, C.E. The Relationship between Acceptance of Cancer and Distress: A Meta-Analytic Review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2019, 71, 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Preacher, K.J.; Rucker, D.D.; Hayes, A.F. Addressing Moderated Mediation Hypotheses: Theory, Methods, and Prescriptions. Multivar. Behav. Res. 2007, 42, 185–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krok, D.; Telka, E. Kwestionariusz Bólu Totalnego [The Total Pain Questionnaire (TPQ)]; Instytut Psychologii UO: Opole, Poland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, S.; Kamarck, T.; Mermelstein, R. A Global Measure of Perceived Stress. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1983, 24, 385–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juczynski, Z.; Oginska-Bulik, N. PSS-10 Skala Odczuwanego Stresu [The Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-10)]; Pracownia Testów Psychologicznych PTP: Warszawa, Poland, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Schwarzer, R.; Jerusalem, M. Generalized Self-Efficacy Scale. In Measures in Health Psychology: A User’s Portfolio. Causal and Control Beliefs; Weinman, J., Wright, S., Johnston, M., Eds.; Nfer-Nelson: Windsor, UK, 1995; pp. 35–37. [Google Scholar]

- Schwarzer, R.; Jerusalem, M.; Juczynski, Z. Skala Uogólnionej Własnej Skuteczności [Self-Efficacy Scale]. In Narzędzia Pomiaru w Promocji i Psychologii Zdrowia [Measurement Tools in Health Promotion and Psychology]; Pracownia Testów Psychologicznych PTP: Warszawa, Poland, 2001; pp. 93–98. [Google Scholar]

- Janowski, K.; Steuden, S.; Pietrzak, A.; Krasowska, D.; Kaczmarek, Ł.; Gradus, I.; Chodorowska, G. Social Support and Adaptation to the Disease in Men and Women with Psoriasis. Arch. Dermatol. Res. 2012, 304, 421–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Buchner, A.; Lang, A.-G. Statistical Power Analyses Using G* Power 3.1: Tests for Correlation and Regression Analyses. Behav. Res. Methods 2009, 41, 1149–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.-Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common Method Biases in Behavioral Research: A Critical Review of the Literature and Recommended Remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairchild, A.J.; MacKinnon, D.P.; Taborga, M.P.; Taylor, A.B. R2 Effect-Size Measures for Mediation Analysis. Behav. Res. Methods 2009, 41, 486–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Puente, C.P.; Furlong, L.V.; Gallardo, C.É.; Mendez, M.C.; Cruz, D.B.; Fernández-de-Las-Peñas, C. Self-Efficacy and Affect as Mediators between Pain Dimensions and Emotional Symptoms and Functional Limitation in Women with Fibromyalgia. Pain Manag. Nurs. 2015, 16, 60–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riva, P.; Wirth, J.H.; Williams, K.D. The Consequences of Pain: The Social and Physical Pain Overlap on Psychological Responses. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2011, 41, 681–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosher, C.E.; Krueger, E.; Secinti, E.; Johns, S.A. Symptom Experiences in Advanced Cancer: Relationships to Acceptance and Commitment Therapy Constructs. Psycho-Oncology 2021, 30, 1485–1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kupst, M.J.; Butt, Z.; Stoney, C.M.; Griffith, J.W.; Salsman, J.M.; Folkman, S.; Cella, D. Assessment of Stress and Self-Efficacy for the NIH Toolbox for Neurological and Behavioral Function. Anxiety Stress Coping 2015, 28, 531–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

| Variables | M | SD | 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | 9. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 61.26 | 12.77 | — | ||||||||

| 3.21 | 2.42 | −0.10 | — | |||||||

| 3.74 | 2.42 | −0.13 * | 0.57 *** | — | ||||||

| 3.05 | 2.29 | −0.18 ** | 0.61 *** | 0.74 *** | — | |||||

| 3.15 | 2.21 | −0.12 * | 0.59 *** | 0.69 *** | 0.81 *** | — | ||||

| 3.29 | 2.02 | −0.15 * | 0.80 *** | 0.87 *** | 0.81 *** | 0.84 *** | – | |||

| 3.01 | 0.53 | 0.11 | −0.15 * | −0.26 *** | −0.33 *** | −0.29 *** | −0.29 *** | – | ||

| 2.71 | 0.98 | −0.18 ** | 0.42 *** | 0.38 *** | 0.51 *** | 0.44 *** | 0.50 *** | −0.05 | – | |

| 2.88 | 0.50 | 0.18 ** | −0.24 *** | −0.40 *** | −0.41 *** | −0.33 *** | 0.40 *** | 0.48 *** | −0.28 *** | |

| 4.58 | 3.41 | 0.07 | −0.08 | −0.29 *** | −0.32 *** | −0.11 | −0.20 ** | 0.26 *** | −0.21 ** | 0.08 |

| Variables | B | SE | t [LLCI, ULCI] | Model R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct effects | ||||

| Physical pain–Self-efficacy | −0.14 | 0.01 | −2.40 [−0.06, −0.01] | 0.02 * |

| Self-efficacy–Illness acceptance | 0.46 | 0.05 | 8.61 [0.34, 0.53] | |

| Physical pain–Illness acceptance | −0.17 | 0.01 | −3.18 [−0.06, −0.01] | 0.26 *** |

| Psychological pain–Self-efficacy | −0.26 | 0.01 | −4.42 [−0.08, −0.03] | 0.07 *** |

| Self-efficacy–Illness acceptance | 0.41 | 0.05 | 7.71 [0.29, 0.48] | |

| Psychological pain–Illness acceptance | −0.29 | 0.01 | −5.54 [−0.08, −0.04] | 0.31 *** |

| Social pain–Self-efficacy | −0.33 | 0.01 | −5.64 [−0.10, −0.05] | 0.11 *** |

| Self-efficacy–Illness acceptance | 0.39 | 0.05 | 7.22 [0.27, 0.47] | |

| Social pain–Illness acceptance | −0.28 | 0.01 | −5.23 [−0.09, −0.04] | 0.31 *** |

| Spiritual pain–Self-efficacy | −0.28 | 0.02 | −4.92 [−0.10, −0.04] | 0.08 *** |

| Self-efficacy–Illness acceptance | 0.43 | 0.05 | 7.76 [0.30, 0.51] | |

| Spiritual pain–Illness acceptance | −0.20 | 0.01 | −3.70 [−0.07, −0.02] | 0.27 *** |

| Total pain-Self–efficacy | −0.29 | 0.02 | −5.01 [−0.11, −0.05] | 0.09 *** |

| Self-efficacy–Illness acceptance | 0.38 | 0.05 | 7.50 [0.28, 0.48] | |

| Total pain–Illness acceptance | −0.28 | 0.01 | −5.18 [−0.09, −0.04] | 0.30 *** |

| Indirect effect | Effect | SE | LLCI | ULCI |

| Physical pain–Self-efficacy–Illness acceptance | −0.07 | 0.03 | −0.13 | −0.01 |

| Psychological pain–Self-efficacy–Illness acceptance | −0.11 | 0.03 | −0.17 | −0.05 |

| Social pain–Self-efficacy–Illness acceptance | −0.13 | 0.03 | −0.20 | −0.08 |

| Spiritual pain–Self-efficacy–Illness acceptance | −0.12 | 0.04 | −0.20 | −0.06 |

| Total pain–Self-efficacy–Illness acceptance | −0.12 | 0.03 | −0.18 | −0.06 |

| R2 mediation effect size | ||||

| Physical pain–Self-efficacy–Illness acceptance | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.07 |

| Psychological pain–Self-efficacy–Illness acceptance | 0.08 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.14 |

| Social pain–Self-efficacy–Illness acceptance | 0.10 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.16 |

| Spiritual pain–Self-efficacy–Illness acceptance | 0.07 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.13 |

| Total pain–Self-efficacy–Illness acceptance | 0.08 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.15 |

| Variables | B | SE | t [LLCI, ULCI] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| INTERACTIVE EFFECTS | ||||

| Physical pain as independent variable | ||||

| Interaction 1: Physical pain × Stress | 0.04 | 0.01 | 2.96 [0.01, 0.07] | |

| Interaction 2: Physical pain × Stress | −0.01 | 0.01 | −0.21 [−0.02, 0.02] | |

| Psychological pain as independent variable | ||||

| Interaction 1: Psychological pain × Stress | 0.02 | 0.01 | 1.10 [−0.01, 0.04] | |

| Interaction 2: Psychological pain × Stress | 0.02 | 0.01 | 1.63 [−0.01, 0.03] | |

| Social pain as independent variable | ||||

| Interaction 1: Social pain × Stress | 0.04 | 0.01 | 2.61 [0.01, 0.06] | |

| Interaction 2: Social pain × Stress | 0.01 | 0.01 | 1.08 [−0.01, 0.04] | |

| Spiritual pain as independent variable | ||||

| Interaction 1: Spiritual pain × Stress | 0.04 | 0.01 | 2.75 [0.01, 0.07] | |

| Interaction 2: Spiritual pain × Stress | 0.02 | 0.01 | 1.24 [−0.01, 0.03] | |

| Total pain as independent variable | ||||

| Interaction 1: Total pain × Stress | 0.04 | 0.01 | 2.62 [0.01, 0.07] | |

| Interaction 2: Total pain × Stress | 0.02 | 0.01 | 1.12 [−0.01, 0.04] | |

| CONDITIONAL DIRECT EFFECTS | Effect | SE | LLCI | ULCI |

| Low stress × Physical pain | −0.01 | 0.01 | −0.05 | 0.02 |

| High stress × Physical pain | −0.01 | 0.01 | −0.04 | 0.01 |

| Low stress × Psychological pain | −0.07 | 0.02 | −0.10 | −0.03 |

| High stress × Psychological pain | −0.03 | 0.02 | −0.06 | −0.01 |

| Low stress × Social pain | −0.06 | 0.02 | −0.10 | −0.02 |

| High stress × Social pain | −0.03 | 0.02 | −0.07 | −0.01 |

| Low stress × Spiritual pain | −0.04 | 0.02 | −0.08 | −0.01 |

| High stress × Spiritual pain | −0.01 | 0.02 | −0.04 | 0.02 |

| Low stress × Total pain | −0.06 | 0.02 | −0.10 | −0.02 |

| High stress × Total pain | −0.04 | 0.02 | −0.07 | −0.01 |

| CONDITIONAL INDIRECT EFFECTS | Effect | SE | LLCI | ULCI |

| Low stress × Physical pain | −0.03 | 0.01 | −0.06 | −0.01 |

| High stress × Physical pain | 0.01 | 0.01 | −0.02 | 0.02 |

| Low stress × Psychological pain | −0.03 | 0.01 | −0.05 | −0.01 |

| High stress × Psychological pain | −0.02 | 0.01 | −0.04 | −0.01 |

| Low stress × Social pain | −0.05 | 0.01 | −0.08 | −0.03 |

| High stress × Social pain | −0.02 | 0.01 | −0.05 | −0.01 |

| Low stress × Spiritual pain | −0.05 | 0.01 | −0.08 | −0.02 |

| High stress × Spiritual pain | −0.02 | 0.01 | −0.04 | −0.01 |

| Low stress × Total pain | −0.05 | 0.01 | −0.08 | −0.02 |

| High stress × Total pain | −0.03 | 0.01 | −0.05 | −0.01 |

| INDEX OF MODERATED MEDIATION | ||||

| Physical pain as independent variable | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.04 |

| Psychological pain as independent variable | 0.01 | 0.01 | −0.01 | 0.02 |

| Social pain as independent variable | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.001 | 0.02 |

| Spiritual pain as independent variable | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.03 |

| Total pain as independent variable | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.005 | 0.03 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Krok, D.; Telka, E.; Zarzycka, B. Total Pain and Illness Acceptance in Pelvic Cancer Patients: Exploring Self-Efficacy and Stress in a Moderated Mediation Model. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 9631. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19159631

Krok D, Telka E, Zarzycka B. Total Pain and Illness Acceptance in Pelvic Cancer Patients: Exploring Self-Efficacy and Stress in a Moderated Mediation Model. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(15):9631. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19159631

Chicago/Turabian StyleKrok, Dariusz, Ewa Telka, and Beata Zarzycka. 2022. "Total Pain and Illness Acceptance in Pelvic Cancer Patients: Exploring Self-Efficacy and Stress in a Moderated Mediation Model" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 15: 9631. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19159631

APA StyleKrok, D., Telka, E., & Zarzycka, B. (2022). Total Pain and Illness Acceptance in Pelvic Cancer Patients: Exploring Self-Efficacy and Stress in a Moderated Mediation Model. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(15), 9631. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19159631