Evolution of Legislation and the Incidence of Elective Abortion in Spain: A Retrospective Observational Study (2011–2020)

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Location and Population

2.2. Variables

2.3. Data Analysis

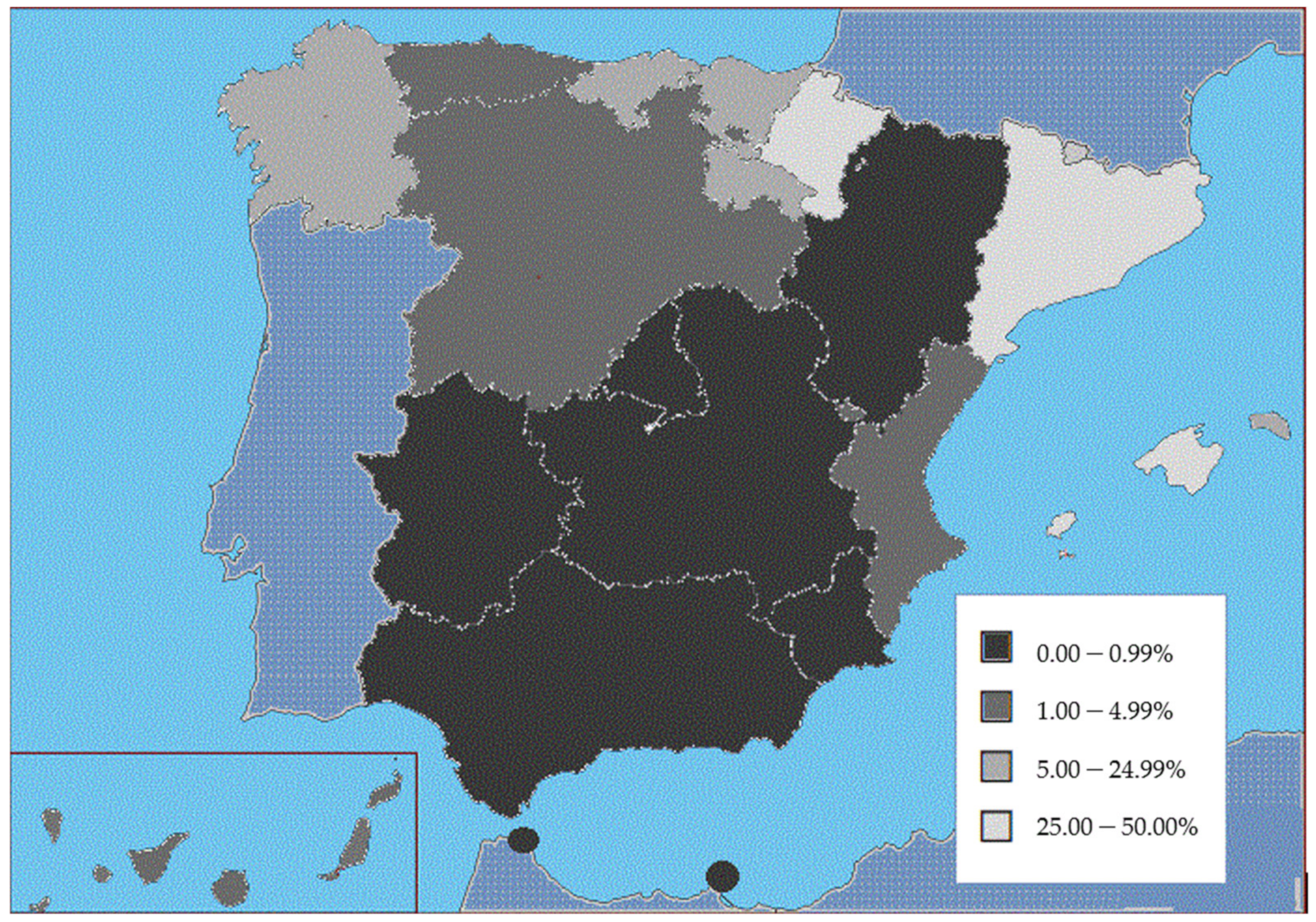

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization (WHO); Department of Reproductive Health and Research. Preventing Unsafe Abortion, World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019.

- Bearak, J.; Popinchalk, A.; Ganatra, B.; Moller, A.B.; Tunçalp, Ö.; Beavin, C.; Kwok, L.; Alkema, L. Unintended pregnancy and abortion by income, region, and the legal status of abortion: Estimates from a comprehensive model for 1990–2019. Lancet Glob Health 2020, 8, e1152–e1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganatra, B.; Gerdts, C.; Rossier, C.; Johnson, B.R.; Tunçalp, Ö.; Assifi, A.; Sedgh, G.; Singh, S.; Bankole, A.; Popinchalk, A.; et al. Global, regional, and subregional classification of abortions by safety, 2010–2014: Estimates from a Bayesian hieralchical model. Lancet 2017, 390, 2372–2381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sedgh, G.; Bearak, J.; Singh, S.; Bankole, A.; Popinchalk, A.; Ganatra, B.; Rossier, C.; Gerdts, C.; Tunçalp, Ö.; Johnson, B.R.; et al. Abortion incidence between 1990 and 2014: Global, regional, and subregional levels and trends. Lancet 2016, 388, 258–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Levels, M.; Sluiter, R.; Need, A. A review of abortion laws in Western-European countries. A cross-national comparison of legal developments between 1960 and 2010. Health Policy 2014, 118, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Parliament. Resolution on Sexual and Reproductive Health and Reproductive Health Rights (2001/2128(INI)). 2001. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/sides/getDoc.do?pubRef=-//EP//NONSGML+TA+P5-TA-2002-0359+0+DOC+PDF+V0//ES (accessed on 11 September 2021).

- Government of Ireland. Health (Regulation of Termination of Pregnancy) Act. 2018. Available online: http://www.irishstatutebook.ie/eli/2018/act/31/enacted/en/html(accessed on 16 March 2022).

- Zaręba, K.; Herman, K.; Kołb-Sielecka, E.; Jakiel, G. Abortion in Countries with Restrictive Abortion Laws—Possible Directions and Solutions from the Perspective of Poland. Healthcare 2021, 9, 1594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gravino, G.; Caruana-Finkel, L. Abortion and methods of reproductive planning: The views of Malta’s medical doctor cohort. Sex Reprod. Health Matters 2019, 27, 1683127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Spain Head of State. Organic Law 9/1985, of July 5, 1985, de Reforma del Artículo 417 bis del Código Penal. Official State Bulletin, 12 July 1985; No. 166. [Google Scholar]

- Spain Head of State. Organic Law 2/2010, of March 3, 2010, on Sexual and Reproductive Health and the Voluntary Interruption of Pregnancy. Official State Bulletin, 4 March 2010; No. 55. [Google Scholar]

- Foster, D.G. The Court is ignoring science. Science 2022, 376, 779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministry of Health. Goberment of Spain. Interrupciones Voluntarias del Embarazo. Available online: https://www.sanidad.gob.es/profesionales/saludPublica/prevPromocion/embarazo/home.htm (accessed on 22 February 2022).

- Wafa, H.A.; Wolfe, C.D.A.; Emmett, E.; Roth, G.A.; Johnson, C.O.; Wang, Y. Burden of Stroke in Europe: Thirty-Year Projections of Incidence, Prevalence, Deaths, and Disability-Adjusted Life Years. Stroke 2020, 51, 2418–2427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministry of Health and Social Welfare. Order of June 21, 2010, of the Ministry of Health and Social Welfare, which regulates the composition and operation of the Clinical Committee of the Health Service of Castilla-La Mancha for the voluntary interruption of pregnancy. Diario Oficial de Castilla- La Mancha, 30 June 2010; No. 124. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health and Social Welfare. Order of June 21, 2010, of the Ministry of Health and Social Welfare establishing the procedure for conscientious objection to elective abortion. Diario Oficial de Castilla-La Mancha, 30 June 2010; No. 124. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health of the Canary Islands. Order of June 30, of the Ministry of Health by which Clinical Committees of Article 15(c) of the Organic Law 2/2010, of March 3, on sexual and reproductive health and voluntary interruption of pregnancy are established in the Autonomous Community of the Canary Islands. Boletín Oficial de Canarias, 5 July 2010; No. 130. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health of the Canary Islands. Order of July 15, 2010, of the Regional Ministry of Health correcting errors in the Order of June 30, 2010. Boletín Oficial de Canarias, 16 July 2010; No. 130. [Google Scholar]

- Regional Ministry of Health and Health Services of Asturias. Resolution of July 2, 2010, appointing the Clinical Committee created by the Organic Law 2/2010, of March 3, on sexual and reproductive health and voluntary interruption of pregnancy. Boletín Oficial de Principado de Asturias, 3 July 2010; No. 153. [Google Scholar]

- Agencia Valenciana de Salud. Resolution of July 2, 2010, of the manager of the Valencian Health Agency, by which the clinical committees contemplated by the Organic Law 2/2010, of March 3, on Sexual and Reproductive Health and voluntary interruption of pregnancy are designated. Diario Oficial de la Comunidad Valenciana, 7 July 2010; No. 6305. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health and Consumption of Aragon. Order of July 5, 2010, by which certain aspects of the Organic Law 2/2010, of March 3, on sexual and reproductive health and voluntary interruption of pregnancy are developed. Boletín Oficial de Aragón, 8 July 2010; No. 133. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health of Cantabria. Order SAN/8/2010, of July 5, 2010, regulating the clinical committee for elective abortion in Cantabria. Boletín Oficial de Cantabria, 12 July 2010; No. 133. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health of Catalonia. Resolution SLT/2260/2010, of July 5, on the appointment of the physicians who conform the clinical committee foreseen in article 15(c) of Law 2/2010, of March 3, on sexual and reproductive health and elective abortion. Diari Oficial de la Generalitat de Catalunya, 8 July 2010; No. 5666. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health of Catalonia. Resolution SLT/937/2013, April 23, by which a clinical committee for intervention in cases of elective abortion for medical reasons is constituted at the Hospital Clínic i Provincial de Barcelona and its members are appointed. Diari Oficial de la Generalitat de Catalunya, 5 July 2013; No. 6412. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health of Castilla y León. Order SAN 954/2010, of July 2, 2010, designating the Clinical Committees of the Castilla y León Health Service. Boletín Oficial de Castilla y León, 5 July 2010; No. 127. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health of Castilla y León. Order SAN 961/2010, of July 2, 2010, designating the Clinical Committees of the Castilla y León Health Service. Boletín Oficial de Castilla y León, 5 July 2010; No. 127. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health and Consumer Affairs of the Basque Country. Order of July 6, 2010, of the Regional Minister of Health and Consumer Affairs, appointing the members of the Clinical Committee for the Autonomous Community of the Basque Country provided for in Law 2/2010, on sexual and reproductive health and voluntary termination of pregnancy. Boletín Oficial del País vasco, 22 July 2010; No. 140. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Navarra. Order 73/2010, of August 3, 2010, of the Regional Minister of Health, by which the Clinical Committee is created to intervene in the case of elective abortion for medical reasons provided for in Article 15(c) of the Organic Law 2/2010, of March 3, 2010, on sexual and reproductive health and voluntary interruption of pregnancy. Boletín Oficial de Navarra, 10 September 2010; No. 110. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Navarra. Foral Order 116/2011, of October 3, which creates the computerized file under the name of “Registry of health professionals who are conscientious objectors in relation to voluntary interruption of pregnancy”. Boletín Oficial de Navarra, 25 October 2011; No. 212. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health and Consumption of the Balearic Islands. Order of August 6, 2010, determining the composition and operation of the Clinical Committee of the Autonomous Community of the Balearic Islands for voluntary interruption of pregnancy. Boletín Oficial de las Islas Baleares, 24 August 2010; No. 124. [Google Scholar]

- Extremadura Department of Health and Dependency. Order of March 4, 2011, regulating the composition and operation of the Clinical Committee of the Autonomous Community of Extremadura for voluntary interruption of pregnancy. Diario Oficial de Extremadura, 11 March 2011; No. 49. [Google Scholar]

- Galician Ministry of Health. Order of March 12, 2012, appointing the members of the clinical committee referred to in Articles 15 and 16 of Organic Law 2/2010, of March 3. Diario Oficial de Galicia, 26 March 2012; No. 59. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health and Social Services of La Rioja. Resolution of the Regional Minister of Health and Social Services, appointing the members of the Clinical Committee referred to in Law 2/2010, on sexual and reproductive health and voluntary interruption of pregnancy. Boletín Oficial de La Rioja, 13 March 2013; No. 35. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health of Madrid. Order 776/2015, of August 4, of the Regional Minister of Health, appointing members of the Clinical Committee for voluntary interruption of pregnancy in the Community of Madrid. Boletín Oficial de la Comunidad de Madrid, 21 August 2015; No. 198. [Google Scholar]

- Junta de Andalucía. Order of June 26, 2017, makes new appointment, for the 2-year term of the members of the clinical committees provided for in Article 15(c) of the Organic Law 2/2010, of March 3, on sexual and reproductive health and voluntary interruption of pregnancy. Boletín Oficial de la Junta de Andalucía, 30 June 2017; No. 124. [Google Scholar]

- Murcia Ministry of Health. Resolution of the Managing Director of the Murcian Health Service appointing the members of the Clinical Committee regulated in Article 2 of Royal Decree 825/2010, of June 25, of partial development of the Organic Law 2/2010, on sexual and reproductive health and voluntary interruption of pregnancy. Boletín Oficial de la Región de Murcia, 24 April 2018; No. 93. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health. Goberment of Spain. In Sistema Nacional de Salud. 2012. Available online: https://www.sanidad.gob.es/organizacion/sns/libroSNS.htm (accessed on 19 March 2022).

- Women’s Link Worldwide. Obstáculos Para Acceder al Aborto en España. 2021. Available online: https://www.womenslinkworldwide.org/files/3151/obstaculos-al-aborto-en-espana.pdf (accessed on 19 March 2022).

- Abort Report. European Data, New 2020 Data. 2020. Available online: https://abort-report.eu/europe/ (accessed on 19 March 2022).

- Sociedad Española de Ginecología y Obstetricia. Control prenatal del embarazo normal. Prog. Obstet Ginecol. 2018, 61, 510–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González de Agüero, R.; Pérez Hiraldo, M.P.; Fabre, E. Diagnóstico prenatal de los defectos congénitos. In Obstetricia; González Merlo, J., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2006; Volume 14, pp. 229–255. [Google Scholar]

- Eurostat. Women in the EU Are Having Their First Child Later. 2021. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/products-eurostat-news/-/ddn-20210224-1#:~:text=In%202019%2C%20the%20mother’s%20age,and%20Romania%20(26.9%20years) (accessed on 20 March 2022).

| Region | Regulations on Regional Clinical Committees | Registry of Conscientious Objector Professionals |

|---|---|---|

| Castilla-La Mancha | 2010: Order of 21 June 2010, of the Ministry of Health and Social Welfare, which regulates the composition and operation of the Clinical Committee of the Health Service of Castilla-La Mancha for the voluntary interruption of pregnancy [15]. | 2010: Order of 21 June 2010, of the Ministry of Health and Social Welfare establishing the procedure for conscientious objection to elective abortion [16]. |

| Canary Islands | 2010: Order of June 30, of the Ministry of Health by which Clinical Committees of Article 15(c) of the Organic Law 2/2010, of March 3, on sexual and reproductive health and voluntary interruption of pregnancy are established in the Autonomous Community of the Canary Islands [17]. 2010: Order of 15 July 2010, of the Regional Ministry of Health correcting errors in the Order of 30 June 2010 [18]. | Not created |

| Asturias | 2010: Resolution of 2 July 2010, appointing the Clinical Committee created by the Organic Law 2/2010, of 3 March, on sexual and reproductive health and voluntary interruption of pregnancy [19]. | Not created |

| Valencia | 2010: Resolution of 2 July 2010, of the manager of the Valencian Health Agency, by which the clinical committees contemplated by the Organic Law 2/2010, of 3 March, on Sexual and Reproductive Health and voluntary interruption of pregnancy are designated [20]. | Not created |

| Aragon | 2010: Order of 5 July 2010, by which certain aspects of the Organic Law 2/2010, of 3 March, on sexual and reproductive health and voluntary interruption of pregnancy, are developed [21]. | Not created |

| Cantabria | 2010: Order SAN/8/2010, of 5 July 2010, regulating the clinical committee for elective abortion in Cantabria [22]. | Not created |

| Catalonia | 2010: Resolution SLT/2260/2010, of 5 July, on the appointment of the physicians who conform the clinical committee foreseen in article 15(c) of Law 2/2010, of 3 March, on sexual and reproductive health and elective abortion [23]. 2013: Resolution SLT/937/2013, 23 April, by which a clinical committee for intervention in cases of elective abortion for medical reasons is constituted at the Hospital Clínic I Provincial de Barcelona and its members are appointed [24]. | Not created |

| Castilla-León | 2010: Order SAN 954/2010, of 2 July 2010, designating the Clinical Committees of the Castilla y León Health Service [25]. 2010: Order SAN 961/2010, of 2 July 2010, designating the Clinical Committees of the Castilla y León Health Service [26]. | Not created |

| Basque Country | 2010: Order of 6 July 2010, of the Regional Minister of Health and Consumer Affairs, appointing the members of the Clinical Committee for the Autonomous Community of the Basque Country provided for in Law 2/2010, on sexual and reproductive health and voluntary termination of pregnancy [27]. | Not created |

| Navarra | 2010: Order 73/2010, of 3 August 2010, of the Regional Minister of Health, by which the Clinical Committee is created to intervene in the case of elective abortion for medical reasons provided for in Article 15(c) of the Organic Law 2/2010, of 3 March 2010, on sexual and reproductive health and voluntary interruption of pregnancy [28]. | 2011: Foral Order 116/2011, of October 3, which creates the computerized file under the name of “Registry of health professionals who are conscientious objectors in relation to voluntary interruption of pregnancy” [29]. |

| Balearic Islands | 2010: Order of 6 August 2010, determining the composition and operation of the Clinical Committee of the Autonomous Community of the Balearic Islands for voluntary interruption of pregnancy [30]. | Not created |

| Extremadura | 2011: Order of 4 March 2011, regulating the composition and operation of the Clinical Committee of the Autonomous Community of Extremadura for voluntary interruption of pregnancy [31]. | Not created |

| Galicia | 2012: Order of 12 March 2012, appointing the members of the clinical committee referred to in Articles 15 and 16 of Organic Law 2/2010, of March 3 [32]. | Not created |

| La Rioja | 2013: Resolution of the Regional Minister of Health and Social Services, appointing the members of the Clinical Committee referred to in Law 2/2010, on sexual and reproductive health and voluntary interruption of pregnancy [33]. | Not created |

| Madrid | 2015: Order 776/2015, of 4 August, of the Regional Minister of Health, appointing members of the Clinical Committee for voluntary interruption of pregnancy in the Community of Madrid [34]. | Not created |

| Andalusia | 2017: Order of 26 June 2017, makes new appointment, for the 2-year term of the members of the clinical committees provided for in Article 15(c) of the Organic Law 2/2010, of March 3, on sexual and reproductive health and voluntary interruption of pregnancy [35]. | Not created |

| Murcia | 2018: Resolution of the Managing Director of the Murcian Health Service appointing the members of the Clinical Committee regulated in Article 2 of Royal Decree 825/2010, of 25 June, of partial development of the Organic Law 2/2010, on sexual and reproductive health and voluntary interruption of pregnancy [36]. | Not created |

| Rates per 1000 Women between 15 and 44 Years of Age | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | Average Annual Rate 2011–2020 | Average Annual Percentage Change 2011–2019 | Average Annual Percentage Change 2011–2020 | |

| Ceuta and Melilla | 4.59 | 4.50 | 3.74 | 3.53 | 3.72 | 5.06 | 4.80 | 3.50 | 2.26 | 1.94 | 3.76 | −6.34% | −7.21% |

| La Rioja | 8.62 | 8.23 | 6.78 | 6.19 | 5.64 | 6.04 | 6.09 | 6.91 | 6.18 | 5.86 | 6.65 | −3.61% | −3.79% |

| Madrid | 15.14 | 14.90 | 14.62 | 12.58 | 12.54 | 12.51 | 13.07 | 12.74 | 13.05 | 10.94 | 13.21 | −1.70% | −3.31% |

| Galicia | 7.76 | 7.01 | 6.78 | 6.78 | 6.60 | 6.57 | 6.51 | 6.50 | 6.41 | 5.71 | 6.66 | −2.31% | −3.27% |

| Aragón | 11.43 | 10.83 | 10.09 | 8.58 | 9.53 | 9.13 | 9.34 | 9.19 | 9.03 | 8.50 | 9.57 | −2.65% | −3.01% |

| Cantabria | 10.36 | 9.90 | 9.19 | 8.60 | 8.80 | 8.01 | 7.55 | 7.75 | 8.45 | 7.89 | 8.65 | −2.34% | −2.82% |

| Murcia | 14.39 | 13.32 | 12.56 | 11.32 | 11.07 | 10.82 | 10.99 | 11.68 | 12.07 | 11.25 | 11.95 | −2.04% | −2.57% |

| Balearic Islands | 15.00 | 13.01 | 13.06 | 12.26 | 13.03 | 13.30 | 13.94 | 13.92 | 13.88 | 11.87 | 13.33 | −0.78% | −2.31% |

| Castilla-La Mancha | 9.92 | 9.60 | 8.97 | 8.00 | 7.38 | 7.31 | 7.48 | 7.99 | 8.66 | 8.00 | 8.33 | −1.47% | −2.15% |

| Canary Islands | 13.16 | 12.79 | 13.03 | 11.87 | 11.58 | 11.41 | 11.29 | 11.56 | 12.10 | 10.88 | 11.97 | −0.97% | −1.98% |

| Valencia | 10.22 | 9.47 | 9.58 | 8.67 | 7.85 | 7.87 | 8.06 | 9.17 | 9.47 | 8.38 | 8.87 | −0.68% | −1.88% |

| Andalucía | 13.09 | 13.08 | 11.91 | 10.62 | 10.59 | 10.38 | 10.38 | 11.29 | 11.98 | 10.85 | 11.42 | −0.90% | −1.85% |

| Castilla-León | 7.75 | 7.25 | 7.11 | 6.14 | 6.33 | 6.05 | 6.21 | 6.60 | 7.05 | 6.56 | 6.71 | −0.95% | −1.62% |

| Extremadura | 7.57 | 7.20 | 7.12 | 6.22 | 5.89 | 6.15 | 6.06 | 6.71 | 6.43 | 6.43 | 6.58 | −1.81% | −1.60% |

| Asturias | 13.79 | 14.34 | 13.62 | 12.70 | 12.51 | 12.32 | 12.73 | 12.65 | 13.03 | 12.03 | 12.97 | −0.64% | −1.42% |

| Navarra | 8.64 | 8.94 | 7.82 | 7.53 | 8.00 | 8.08 | 7.88 | 7.88 | 8.31 | 7.66 | 8.07 | −0.32% | −1.15% |

| Basque Country | 10.34 | 10.04 | 9.97 | 8.88 | 9.57 | 9.87 | 9.98 | 10.03 | 10.47 | 9.58 | 9.87 | 0.30% | −0.68% |

| Catalonia | 14.49 | 14.28 | 14.18 | 12.59 | 12.70 | 12.80 | 12.89 | 14.05 | 14.72 | 13.44 | 13.61 | 0.35% | −0.66% |

| Total Spain | 12.47 | 12.12 | 11.74 | 10.46 | 10.40 | 10.36 | 10.51 | 11.12 | 11.53 | 10.33 | 11.10 | −0.86% | −1.92% |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pellico-López, A.; Paz-Zulueta, M.; Manjón-Rodríguez, J.B.; Sánchez Movellán, M.; Ajo Bolado, P.; García-Vázquez, J.; Cayón-De las Cuevas, J.; Ruiz-Azcona, L. Evolution of Legislation and the Incidence of Elective Abortion in Spain: A Retrospective Observational Study (2011–2020). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 9674. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19159674

Pellico-López A, Paz-Zulueta M, Manjón-Rodríguez JB, Sánchez Movellán M, Ajo Bolado P, García-Vázquez J, Cayón-De las Cuevas J, Ruiz-Azcona L. Evolution of Legislation and the Incidence of Elective Abortion in Spain: A Retrospective Observational Study (2011–2020). International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(15):9674. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19159674

Chicago/Turabian StylePellico-López, Amada, María Paz-Zulueta, Jimena B. Manjón-Rodríguez, Mar Sánchez Movellán, Purificación Ajo Bolado, José García-Vázquez, Joaquín Cayón-De las Cuevas, and Laura Ruiz-Azcona. 2022. "Evolution of Legislation and the Incidence of Elective Abortion in Spain: A Retrospective Observational Study (2011–2020)" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 15: 9674. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19159674