Wet Nurse or Milk Bank? Evolution in the Model of Human Lactation: New Challenges for the Islamic Population

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

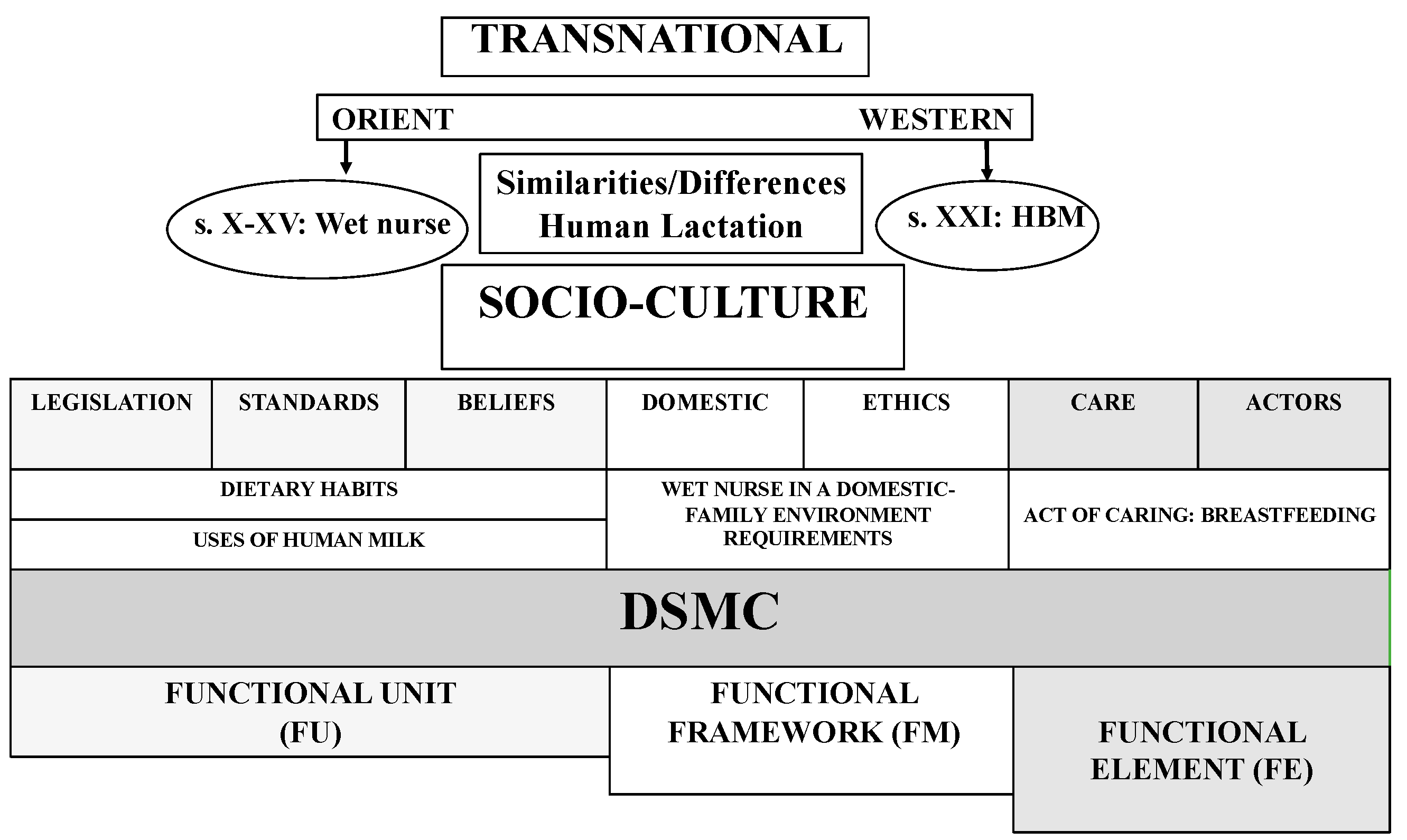

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Search Strategy and Review Process

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Dietary Habits of the Wet Nurse and Shared Recommendations Regarding Disease

3.2. The Socio-Health Value of Human Milk: Milk as an Ingredient for Other Ailments

3.3. The Wet Nurse in the Domestic–Family Environment: Personal and Occupational Requirements

3.4. The Act of Caring through Breastfeeding

3.4.1. A Journey: From the Beginnings of Human Lactation to Weaning

3.4.2. Wet Nurse: Breast Characteristics and Milk States

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DSMC | Dialectical structural model of care |

| FU | Functional unit |

| FF | Functional framework |

| EF | Functional element |

| HMB | Human milk bank |

References

- Fang, M.T.; Grummer-Strawn, L.; Maryuningsih, Y.; Biller-Andorno, N. Human milk banks: A need for further evidence and guidance. Lancet Glob. Health 2021, 9, e104–e105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arabiat, D.H.; Whitehead, L.; Al Jabery, M.A.; Darawad, M.; Geraghty, S.; Halasa, S. Newborn Care Practices of Mothers in Arab Societies: Implication for Infant Welfare. J. Transcult. Nurs. 2018, 30, 260–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- World Health Organization (WHO). The Optimal Duration of Exclusive Breastfeeding: Report of an Expert Consultation. 2001. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/67219/WHO_NHD_01.09.pdf?ua=1 (accessed on 15 December 2021).

- Soler, E. Bancos de Leche, Parentesco de Leche e Islam. Restricciones Alimentarias Entre la Población Infantil en Barcelona. Dilemata 2017, 25, 109–119. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=6124264 (accessed on 15 November 2020).

- Horta, B.L.; Victora, C.G.; Organization, W.H. Short-Term Effects of Breastfeeding: A Systematic Review on the Benefits of Breastfeeding on Diarrhoea and Pneumonia Mortality; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Guidelines on Optimal Feeding of Low Birth-Weight Infants in Lowand Middle-Income Countries; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Mead, M. Masculino y Femenino; Minerva University: Madrid, Spain, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Kaygusuz, M.; Gümüştakım, R.; Kuş, C.; Ipek, S.; Tok, A. TCM use in pregnant women and nursing mothers: A study from Turkey. Complement. Ther. Clin. Pract. 2020, 42, 101300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafari-Mianaei, S.; Alimohammadi, N.; Banki-Poorfard, A.-H.; Hasanpour, M. An inquiry into the concept of infancy care based on the perspective of Islam. Nurs. Inq. 2017, 24, e12198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arabiat, D.; Whitehead, L.; Al Jabery, M.; Towell-Barnard, A.; Shields, L.; Abu Sabah, E. Traditional methods for managing illness in newborns and infants in an Arab society. Int. Nurs. Rev. 2019, 66, 329–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espina-Jerez, B.; Domínguez-Isabel, P.; Gómez-Cantarino, S.; Pina-Queirós, P.J.; Bouzas-Mosquera, C. Una excepción en la trayectoria formativa de las mujeres: Al-Ándalus en los siglos VIII-XII. Cult. Los Cuid. 2019, 23, 194–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar, M.J. Lactancia Materna; Elsevier: Madrid, Spain, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Yalom, M. Historia del Pecho, Primera; Tusquets: Barcelona, Spain, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Espinilla, B. La Elección de Las Nodrizas En Las Clases Altas, Del Siglo XVII al Siglo XIX. Matronas Profesión 2013, 14, 68–73. [Google Scholar]

- Irving, W. Life of Mahomet; George Bell & Sons: London, UK, 1874. [Google Scholar]

- Giladi, A. Muslim Midwives: The Craft of Birthing in the Premodern Middle East; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Siles-González, J.; Romera-Álvarez, L.; Dios-Aguado, M.; Ugarte-Gurrutxaga, M.I.; Gómez-Cantarino, S. Woman, Mother, Wet Nurse: Engine of Child Health Promotion in the Spanish Monarchy (1850–1910). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 9005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Cantarino, S.; Romera-Álvarez, L.; Dios-Aguado, M.; Siles-González, J.; Espina-Jerez, B. La nodriza pasiega: Transición de la actividad biológica a la laboral (1830–1930). Cult. Los Cuid. 2020, 24, 160–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Milk Bank Association (EMBA). Active and Planned Milk Banks. Available online: https://europeanmilkbanking.com/map/ (accessed on 10 April 2021).

- Thorley, V. Milk siblingship, religious and secular: History, applications, and implications for practice. Women Birth 2014, 27, e16–e19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karadag, A.; Ozdemir, R.; Ak, M.; Ozer, A.; Dogan, D.G.; Elkiran, O. Human milk banking and milk kinship: Perspectives of mothers in a Muslim country. J. Trop. Pediatr. 2015, 61, 188–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Onat, G.; Karakoç, H. Informal Breast Milk Sharing in a Muslim Country: The Frequency, Practice, Risk Perception, and Risk Reduction Strategies Used by Mothers. Breastfeed. Med. 2019, 14, 597–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- El-Khuffash, A.; Unger, S. The Concept of Milk Kinship in Islam: Issues Raised When Offering Preterm Infants of Muslim Families Donor Human Milk. J. Hum. Lact. Off. J. Int. Lact. Consult. Assoc. 2012, 28, 125–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaly, M. Human Milk-Based Industry in the Muslim World: Religioethical Challenges. Breastfeed. Med. 2018, 13, S28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shatzmiller, M. Women’s Labour. In Labour in the Medieval Islamic World; Haarmann, U., Ed.; Islamic History and Civilization (formerly Arab History and Civilization). Studies and Texts; E. J. Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands; New York, NY, USA; Köln, Germany, 1994; Volume 4, pp. 347–368. [Google Scholar]

- Fierro, M.I. La mujer y el trabajo en el Corán y el hadiz. In La Mujer en Al-Ándalus: Reflejos Históricos de su Actividad y Categorías Sociales; Colección del Seminario de Estudios de la Mujer; Universidad Autónoma de Madrid: Madrid, Spain, 1989; pp. 35–51. [Google Scholar]

- vila, M.L. Las mujeres “sabias” en Al-Ándalus. In La Mujer en Al-Ándalus: Reflejos Históricos de su Actividad y Categorías Sociales; Viguera, M.J., Ed.; Andaluzas Unidas Madrid: Sevilla, Spain, 1989; pp. 139–184. [Google Scholar]

- Marín, M. Los Saberes de Las Mujeres. In Vidas de Mujeres Andalusíes; Sarriá: Málaga, Spain, 2006; pp. 188–189. [Google Scholar]

- Marín, M. Las Mujeres de Las Clases Sociales Superiores. Al-Ándalus, Desde La Conquista Hasta Finales Del Califato de Córdoba. In La Mujer en al-Ándalus: Reflejos Históricos de su Actividad y Categorías Sociales. Actas de las V Jornadas de Investigación Interdisciplinaria; Viguera, M.J., Ed.; Andaluzas Unidas Madrid: Sevilla, Spain, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez-Roldán, M.F.; Álvarez-Calero, M.; Monroy-Pérez, R.E.; Sánchez-Calama, A.M.; Torralbo-Higuera, A.; Angulo-Concepción, M.B. La «qabila»: Historia de la matrona olvidada de al-Andalus (siglos VIII-XV). Matronas Profesión 2014, 15, 2–8. [Google Scholar]

- Giladi, A. Infants, Parents and Wet Nurses: Medieval Islamic Views on Breastfeeding and Their Social Implications; E. J. Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 1999; Volume 34. [Google Scholar]

- Arroñada, S.N. La Edad de La Inocencia. Visiones Islámica y Cristiana Hispano-Medieval Sobre La Infancia. Meridies 2011, 9, 7–18. [Google Scholar]

- Arroñada, S.N. La Nodriza En La Sociedad Hispano-Medieval. Arqueol. Hist. Viajes Sobre Mundo Mediev. 2008, 27, 44–52. [Google Scholar]

- Siles González, J.; Fernández Sánchez, P.; Pérez Cañaveras, R. La Enfermería Comparada: Un Instrumento Para Canalizar y Sistematizar Las Experiencias y Conocimientos de Una Profesión Transnacional. Enferm. Científica 1992, 124–125, 16–19. [Google Scholar]

- Velandia-Mora, A.L. História Comparada. In Pesquisa em História da Enfermagem; Manole: San Paulo, Brazil, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Siles-Gonzalez, J.; Ruiz, M.S. The convergence process in European Higher Education and its historical cultural impact on Spanish clinical nursing training. Nurse Educ. Today 2012, 32, 887–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munn, Z.; Peters, M.D.J.; Stern, C.; Tufanaru, C.; McArthur, A.; Aromataris, E. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2018, 18, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siles, J. Los Cuidados de Enfermería En El Marco de La Historia Social y La Historia Cultural. In La Transformación de la Enfermería. Nuevas Miradas Para la Historia; González, C., Martínez, F., Eds.; Comares: Granada, Spain, 2010; pp. 219–250. [Google Scholar]

- Siles González, J. Historia Cultural de Enfermería: Reflexión Epistemológica y Metodológica. Av. Enferm. 2010, 28, 120–128. [Google Scholar]

- Siles González, J.; Solano Ruiz, C. El Modelo Estructural Dialéctico de Los Cuidados. Una Guía Facilitadora de La Organización, Análisis y Explicación de Los Datos En Investigación Cualitativa. CIAIQ2016 2016, 2, 211–220. [Google Scholar]

- Ibn Wāfid. El Libro de La Almohada; Álvarez de Morales, C., Ed.; Instituto Provincial de Investigaciones y Estudios Toledanos: Toledo, Spain, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez, J.S.; Ruiz, C.S.; Gutierrez, A.G. International Appraisal of Nursing Culture and Curricula: A Qualitative Study of Erasmus Students. Scientifica 2016, 2016, 6354045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Abū-l-Walid Ibn Rušd “Averroes”. Libro de Las Generalidades de La Medicina. Kitab Al-Kulliyyat Fil-Tibb; Vázquez, M.C., Álvarez de Morales, C., Eds.; Editorial Trotta: Madrid, Spain, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Ibn Sa’īd, ‘Arīb. El Libro de La Generación Del Feto, El Tratamiento de Las Mujeres Embarazadas y de Los Recién Nacidos; Arjona, A., Ed.; Sociedad de pediatría de Andalucía occidental y Extremadura: Sevilla, Spain, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Ibn al-Jatib. Kitab Al-Wusul Li-Hifz al-Sihha Fi-l-Fusul, “Libro de Higiene”. In Traducido al Español Como Libro Del Cuidado de La Salud Durante Las Estaciones Del Año; Vázquez, M.C., Ed.; Universidad de Salamanca: Salamanca, Spain, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Anónimo. La Cocina Hispano-Magrebí Durante La Época Almohade, Siglo XIII, Maestre; Huici Miranda, A., Ed.; Maestre: Madrid, Spain, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- de Anazarbo, D. The Arabic Materia Medica of Dioscorides; Sadek, M.M., Ed.; Es Éditions du Sphinx: Québec, QC, Canada, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Abu l-‘Ala’ Zuhr (Avenzoar). Kitab Al-Muyarrabat (Libro de Las Experiencias Médicas); Álvarez, C., Ed.; CSIC: Madrid, Spain, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Ibn al-Baytar. Kitāb Al-Jami’ Li-Mufradāt al-Adwiya Wa-l-Agdiya, Coleción de Medicamentos y Alimentos; Cabo González, A.M., Ed.; Megablum: Sevilla, Spain, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Diego, J.L.; Bidikov, L.; Pedler, M.G.; Kennedy, J.B.; Quiroz-Mercado, H.; Gregory, D.G.; Petrash, J.M.; McCourt, E.A. Effect of human milk as a treatment for dry eye syndrome in a mouse model. Mol. Vis. 2016, 22, 1095–1102. [Google Scholar]

- Karcz, K.; Walkowiak, M.; Makuch, J.; Olejnik, I.; Królak-Olejnik, B. Non-Nutritional Use of Human Milk Part 1: A Survey of the Use of Breast Milk as a Therapy for Mucosal Infections of Various Types in Poland. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Karcz, K.; Makuch, J.; Walkowiak, M.; Olejnik, I.; Krolak-Olejnik, B. Non-nutritional “paramedical” usage of human milk—Knowledge and opinion of breastfeeding mothers in Poland. Ginekol. Polska 2020, 91, 79–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allam, N.A.; Al Megrin, W.A.; Talat, A.M. The Effect of Topical Application of Mother Milk on Separation of Umbilical Cord for Newborn Babies. Am. J. Nurs. Sci. 2015, 4, 288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahrous, E.S.; Darwish, M.M.; Dabash, S.A.; Marie, I.; Abdelwahab, S.F. Topical Application of Human Milk Reduces Umbilical Cord Separation Time and Bacterial Colonization Compared to Ethanol in Newborns. Transl. Biomed. 2012, 3, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Abbaszadeh, F.; Hajizadeh, Z.; Jahangiri, M. Comparing the Impact of Topical Application of Human Milk and Chlorhexidine on Cord Separation Time in Newborns. Pak. J. Med. Sci. 2016, 32, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Amiri-Farahani, L.; Sharifi-Heris, Z.; Mojab, F. The Anti-Inflammatory Properties of the Topical Application of Human Milk in Dermal and Optical Diseases. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2020, 2020, 4578153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berents, T.L.; Rønnevig, J.; Søyland, E.; Gaustad, P.; Nylander, G.; Løland, B.F. Topical treatment with fresh human milk versus emollient on atopic eczema spots in young children: A small, randomized, split body, controlled, blinded pilot study. BMC Dermatol. 2015, 15, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kasrae, H.; Farahani, L.A.; Yousefichaijan, P. Efficacy of topical application of human breast milk on atopic eczema healing among infants: A randomized clinical trial. Int. J. Dermatol. 2015, 54, 966–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Seifi, B.; Jalali, S.; Heidari, M. Assessment Effect of Breast Milk on Diaper Dermatitis. Dermatol. Rep. 2017, 9, 7044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Asena, L.; Suveren, E.H.; Karabay, G.; Altinors, D.D. Human Breast Milk Drops Promote Corneal Epithelial Wound Healing. Curr. Eye Res. 2016, 42, 506–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Witkowska-Zimny, M.; Kamińska-El-Hassan, E.; Wróbel, E. Milk Therapy: Unexpected Uses for Human Breast Milk. Nutrients 2019, 11, 944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mesned Alesa, M.S. El Estatus de la Mujer en la Sociedad Árabo-Islámica Medieval Entre Oriente y Occidente; Editorial de la Universidad de Granada: Granada, Spain, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Ibn Jaldún; Libro Quinto; Capítulo XXVIII. Del Arte de La Partería. In Introducción a la Historia Universal (Al-Muqaddimah); Feres, J., Ed.; Fondo de Cultura Económica: México City, Mexico, 1997; pp. 729–731. [Google Scholar]

- Safi, N. El Tratamiento de La Mujer Árabe y Hebrea En La Poesía Andalusí; Universidad de Granada: Granada, Spain, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Vázquez, M.C.; Herrera, M.T. Dos Capítulos Sobre Pediatría: Árabe y Castellano. Asclepio 1984, 36, 47–83. [Google Scholar]

- lvarez, C. La Sociedad de Al-Ándalus y La Sexualidad. In Conocer Al-Ándalus, Perspectivas Desde el Siglo XXI; Ediciones Alfar: Sevilla, Spain, 2010; pp. 43–76. [Google Scholar]

- Cortés, J. El Corán; Jomier, J., Ed.; Herder Editorial: Barcelona, Spain, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Benkheira, M. Le Commerce Conjugal Gâte-t-Il Le Lait Maternel? Sexualite, Medecine et Droit Dans Le Sunnisme Ancien. Arabica 2003, 50, 1–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benkheira, M.H. Donner le sein, c’est comme donner le jour: La doctrine de l’allaitement dans le sunnisme medieval. Stud. Islam. 2001, 113, 5–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansen, B. Die Sündige, Gesunde Amme. Welt Islams 1988, 28, 264–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comby, J. Tratado de Las Enfermedades de La Infancia; Salvat e Hijo Editores: Barcelona, Spain, 1899. [Google Scholar]

- Modanlou, H.D. Medical care of children during the golden age of Islamic medicine. Arch. Iran. Med. 2015, 18, 263–265. [Google Scholar]

- Koçtürk, T. Foetal development and breastfeeding in early texts of the Islamic tradition. Acta Paediatr. 2003, 92, 617–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawwas, A.W. Breast feeding as seen by Islam. Popul. Sci. (Cairo Egypt) 1988, 8, 55–58. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO); United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). Global Strategy for Infant and Young Child Feeding; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Asociación Española de Pediatría (AEP); Comité de Nutrición y Lactancia Materna (CNYLM). Lactancia Materna En Niños Mayores o “Prolongada”; Comité de Lactancia Materna: Madrid, Spain, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Marín, M. En Los Márgenes de La Ley: El Consumo de Alcohol En al Andalus. In Estudios onomástico-biográficos de al Andalus (Identidades marginales); De la Puente, C., Ed.; CSIC: España, Spain, 2003; Volume XIII, pp. 271–328. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-Cantarino, S.; Romera-Álvarez, L.; de Dios-Aguado, M.; Ugarte-Gurrutxaga, M.I.; Siles-Gonzalez, J.; Cotto-Andino, M. Queens and Wet Nurses: Indispensable Women in the Dynasty of the Sun King (1540–1580). Healthcare 2022, 10, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Database | Search Strategy | Filters | Points Extracted | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Pubmed Cochrane Cuiden Scopus Web of Science SciELO Books Treatises | breastfeeding AND human milk AND wet nurse AND muslim wet nursing AND muslim history wet nursing AND requirements AND muslim history wet nursing AND milk siblingship AND muslim history wet nursing AND legislation AND muslim human milk AND remedies breastfeeding AND child survival AND (muslim) breastfeeding AND Quran nursing mother AND Quran nursing mother AND traditional medicine wet-nursing AND Middle Ages wet-nursing AND nursing history breastfeeding AND colostrum AND muslim mothers | Last 10 years Article English/Spanish | Dietary habits of wet nurse and infant Therapeutic uses of human milk Domestic–family work. Requirements of the wet nurse Breastfeeding and weaning. Breast and milk characteristics | [26,32,41,43,44,45,46] [41,43,44,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61] [25,26,30,43,44,45,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70] [2,43,44,45,64,65,66,70,71,72,73,74,75,76] |

| Infant Disease | Feeding of the Wet Nurse | Infant Feeding |

|---|---|---|

| Gastroenteritis | Lamb roasted over charcoal fire, previously sprinkled with rose water and quince water. Bread made of wheat and millet flour in different quantities. | A roasted Armenian clay ratl, macerated in a quarter of fresh water. If the infant was thirsty, he/she would be given this water to drink. The clay would act as a filter. A quince yawaris, which was dissolved in rose syrup. |

| Vomiting and diarrhoea | Ten dirhams of roasted Armenian clay with a quarter of water. Eight dirhams of apple yawaris, one habba of musk and partridge meat mixed with quince and rose water. | |

| Source References | Ailment | Remedies |

|---|---|---|

| Ibn Wafid (10th c.) [41] The Pillow Book | Ophthalmia or ocular inflammation that afflicts children. | Separately, starch is put in rose water until it dries. On the other hand, sarcocola is macerated in women’s milk and left to dry. When both preparations are dry, they are pulverised and an equal quantity of both is added to the eye. |

| Dry eye syndrome. | Six or seven times with milk from healthy, breastfeeding women. | |

| Strengthening the eye and sharpening eyesight. | Mother’s milk combined with honey and instilled with a few drops of vinegar. | |

| Abu Zuhr (s. XII) [48] The Book of Medical Experiences | Ophthalmic eye drops. | Woman’s milk or rose water are used as basic diluents for any eye drops. |

| Abundant optic discharge. | Nightly application of egg white or almond milk mashed with women’s milk on the eyelid. | |

| Removal of a foreign body, ocular and eyelid oedema, as well as the onset of a pterygium. | It is used as an ingredient in eye drops to treat these aliments. |

| Fase | Descripción |

|---|---|

| (1) ayat-hu bi-rayyatin wa huwa ‘ayyi | The exact translation is “rearing without mother’s milk”. This phase occurs when weaning occurs prematurely. |

| (2) al-ta’fir | Feeding is combined with periods of breastfeeding. |

| (3) mu’affar | Child stops breastfeeding |

| Milk Status | Natural Remedy |

|---|---|

| Reducing its thickness | The wet nurse had to drink a lot of water. |

| Thick milk | Oxymiel: a beverage made up of a mild wine, water and honey. |

| Very fluid milk | Women would eat foods such as rice, meat and egg yolks, or they would simply have to eat more and heartier foods. |

| Low quantity | The wet nurse drank water with bran and fennel seeds, salted fish heads and wine. |

| Low quantity | This was a matter of great concern, the specific aetiological factor would have to be identified in order to apply an appropriate pharmacological treatment, although some electuaries were also recommended. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Espina-Jerez, B.; Romera-Álvarez, L.; de Dios-Aguado, M.; Cunha-Oliveira, A.; Siles-Gonzalez, J.; Gómez-Cantarino, S. Wet Nurse or Milk Bank? Evolution in the Model of Human Lactation: New Challenges for the Islamic Population. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 9742. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19159742

Espina-Jerez B, Romera-Álvarez L, de Dios-Aguado M, Cunha-Oliveira A, Siles-Gonzalez J, Gómez-Cantarino S. Wet Nurse or Milk Bank? Evolution in the Model of Human Lactation: New Challenges for the Islamic Population. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(15):9742. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19159742

Chicago/Turabian StyleEspina-Jerez, Blanca, Laura Romera-Álvarez, Mercedes de Dios-Aguado, Aliete Cunha-Oliveira, José Siles-Gonzalez, and Sagrario Gómez-Cantarino. 2022. "Wet Nurse or Milk Bank? Evolution in the Model of Human Lactation: New Challenges for the Islamic Population" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 15: 9742. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19159742

APA StyleEspina-Jerez, B., Romera-Álvarez, L., de Dios-Aguado, M., Cunha-Oliveira, A., Siles-Gonzalez, J., & Gómez-Cantarino, S. (2022). Wet Nurse or Milk Bank? Evolution in the Model of Human Lactation: New Challenges for the Islamic Population. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(15), 9742. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19159742