Associations between Muscle Strength, Physical Performance and Cognitive Impairment with Fear of Falling among Older Adults Aged ≥ 60 Years: A Cross-Sectional Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

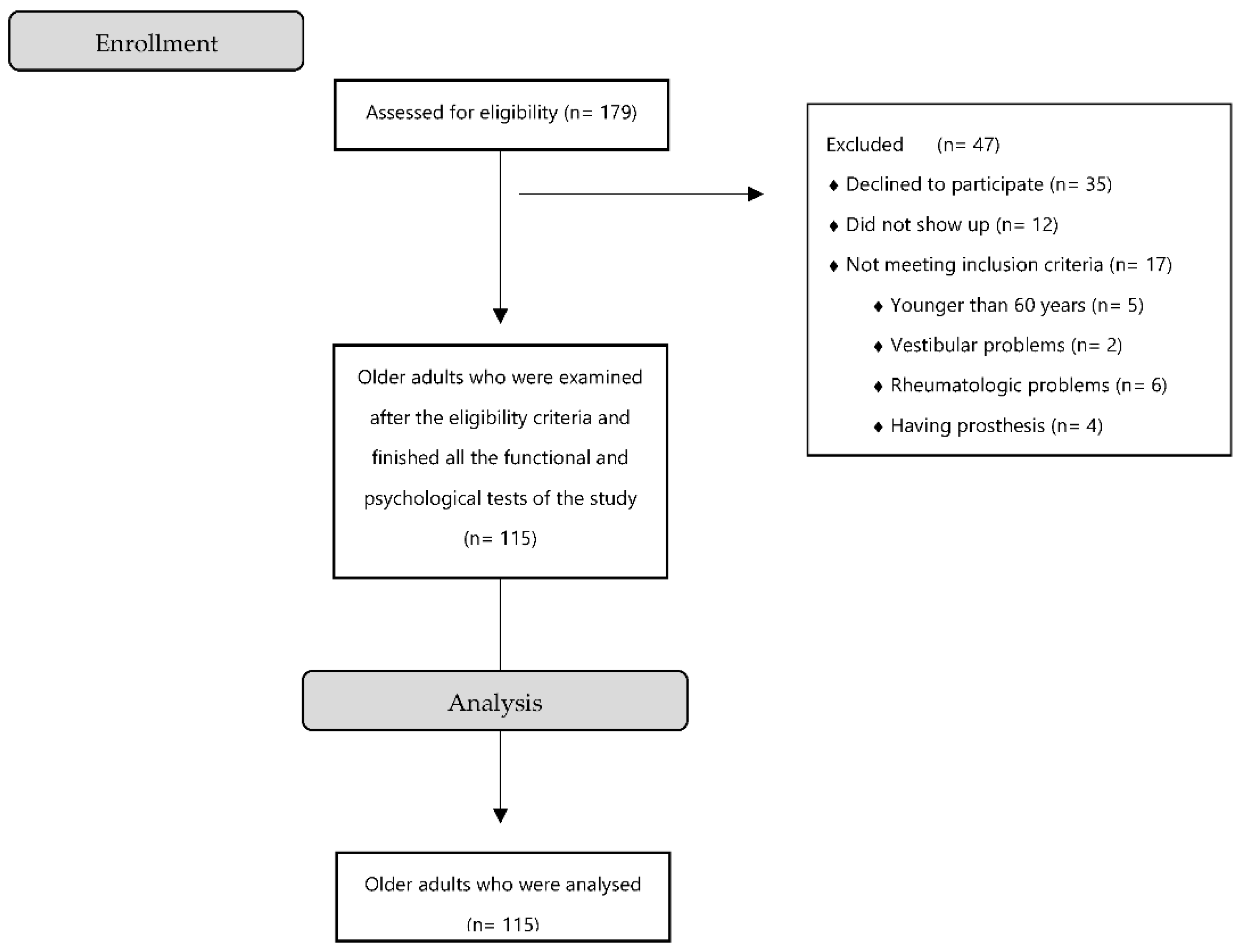

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Study Outcomes

2.2.1. Sociodemographic and Anthropometric Data

2.2.2. Fear of Falling

2.2.3. Lower Limb Strength

2.2.4. Upper Extremity Muscle Strength

2.2.5. Gait Parameters

2.2.6. Semantic and Phonologic Fluency

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Sample Size Calculation

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nelson, M.E.; Rejeski, W.J.; Blair, S.N.; Duncan, P.W.; Judge, J.O.; King, A.C.; Macera, C.A.; Castaneda-Sceppa, C. American College of Sports Medicine; American Heart Association Physical Activity and Public Health in Older Adults: Recommendation from the American College of Sports Medicine and the American Heart Association. Circulation 2007, 116, 1094–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- World Population Prospects-Population Division-United Nations. Available online: https://population.un.org/wpp/Download/Standard/Population/ (accessed on 30 June 2022).

- Scheffer, A.C.; Schuurmans, M.J.; van Dijk, N.; van der Hooft, T.; de Rooij, S.E. Fear of Falling: Measurement Strategy, Prevalence, Risk Factors and Consequences among Older Persons. Age Ageing 2008, 37, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Tinetti, M.E.; Powell, L. 4 fear of falling and low self-efficacy: A cause of dependence in elderly persons. J. Gerontol. 1993, 48, 35–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jørstad, E.C.; Hauer, K.; Becker, C.; Lamb, S.E. ProFaNE Group Measuring the Psychological Outcomes of Falling: A Systematic Review: Fall-Related Psychological Outcome Measures. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2005, 53, 501–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gagnon, N.; Flint, A.J.; Naglie, G.; Devins, G.M. Affective Correlates of Fear of Falling in Elderly Persons. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2005, 13, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vellas, B.J.; Wayne, S.J.; Romero, L.J.; Baumgartner, R.N.; Garry, P.J. Fear of Falling and Restriction of Mobility in Elderly Fallers. Age Ageing 1997, 26, 189–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Salkeld, G. Quality of life related to fear of falling and hip fracture in older women: A time trade off study Commentary: Older people’s perspectives on life after hip fractures. BMJ 2000, 320, 341–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gilbert, R.; Todd, C.; May, M.; Yardley, L.; Ben-Shlomo, Y. Socio-Demographic Factors Predict the Likelihood of Not Returning Home after Hospital Admission Following a Fall. J. Public Health (Oxf.) 2010, 32, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Malini, F.M.; Lourenço, R.A.; Lopes, C.S. Prevalence of Fear of Falling in Older Adults, and Its Associations with Clinical, Functional and Psychosocial Factors: The Frailty in Brazilian Older People-Rio de Janeiro Study: Fear of Falling: FIBRA-RJ Study. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2016, 16, 336–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitdhiraksa, N.; Piyamongkol, P.; Chaiyawat, P.; Chantanachai, T.; Ratta-Apha, W.; Sirikunchoat, J.; Pariwatcharakul, P. Prevalence and Factors Associated with Fear of Falling in Community-Dwelling Thai Elderly. Gerontology 2021, 67, 276–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Arnau, F.M.; Prieto-Contreras, L.; Pérez-Ros, P. Factors Associated with Fear of Falling among Frail Older Adults. Geriatr. Nurs. 2021, 42, 1035–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lavedán, A.; Viladrosa, M.; Jürschik, P.; Botigué, T.; Nuín, C.; Masot, O.; Lavedán, R. Fear of Falling in Community-Dwelling Older Adults: A Cause of Falls, a Consequence, or Both? PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0194967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitorino, L.M.; Teixeira, C.A.B.; Boas, E.L.V.; Pereira, R.L.; Santos, N.O.D.; Rozendo, C.A. Fear of Falling in Older Adults Living at Home: Associated Factors. Rev. Esc. Enferm. USP 2017, 51, e03215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schoene, D.; Heller, C.; Aung, Y.N.; Sieber, C.C.; Kemmler, W.; Freiberger, E. A Systematic Review on the Influence of Fear of Falling on Quality of Life in Older People: Is There a Role for Falls? Clin. Interv. Aging 2019, 14, 701–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Chen, W.-C.; Li, Y.-T.; Tung, T.-H.; Chen, C.; Tsai, C.-Y. The Relationship between Falling and Fear of Falling among Community-Dwelling Elderly. Medicine (Baltim.) 2021, 100, e26492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.-T.; Chen, H.-C.; Chou, P. Factors Associated with Fear of Falling among Community-Dwelling Older Adults in the Shih-Pai Study in Taiwan. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0150612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vo, T.H.M.; Nakamura, K.; Seino, K.; Nguyen, H.T.L.; Van Vo, T. Fear of Falling and Cognitive Impairment in Elderly with Different Social Support Levels: Findings from a Community Survey in Central Vietnam. BMC Geriatr. 2020, 20, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Birhanie, G.; Melese, H.; Solomon, G.; Fissha, B.; Teferi, M. Fear of Falling and Associated Factors among Older People Living in Bahir Dar City, Amhara, Ethiopia- a Cross-Sectional Study. BMC Geriatr. 2021, 21, 586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yardley, L.; Beyer, N.; Hauer, K.; Kempen, G.; Piot-Ziegler, C.; Todd, C. Development and initial validation of the Falls Effi-cacy Scale-International (FES-I). Age Ageing 2005, 34, 614–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lomas, R.; Hita, F.; Mendoza, N.; Martínez-Amat, A. Cross-cultural adaptation and validation of the Falls Efficacy Scale International in Spanish postmenopausal women Menopause. J. N. Am. Menopause Soc. 2012, 19, 904–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guralnik, J.; Simonsick, E.; Ferrucci, L.; Glynn, R.; Berkman, L.; Blazer, D.; Scherr, P.; Wallace, R. A Short Physical Perfor-mance Battery Assessing Lower Extremity Function: Association with Self-Reported Disability and Prediction of Mortality and Nursing Home Admission. Get Access Arrow J. Gerontol. 1994, 49, M85–M94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azizah, M.; Lajoie, Y.; Teasdale, N. Step Length Variability at Gait Initiation in Elderly Fallers and Non-Fallers, and Young Adults. Gerontology 2003, 49, 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeanne, S.; Ho, A. Walking Speed and Stride Length Predicts 36 Months Dependency, Mortality, and Institutionalization in Chinese Aged 70 And Older. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2015, 47, 1257–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, C.Y.; Yoon, H.S.; Kim, H.D.; Kang, K.Y. The effect of the degree of dual-task interference on gait, dual-task cost, cognitive ability, balance, and fall efficacy in people with stroke: A cross-sectional study. Medicine 2021, 100, e26275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez, J.D. High-Intensity Interval Training Using TRS Lower-Body Exercises Improve the Risk of Falls in Healthy Older People. J. Aging Phys. Act. 2018, 27, 325–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benton, A.; Hamsher, S.; Sivan, A. Controlled Oral Word Association Test (COWAT) [Database Record]; APA PsycTests: Worcester, MA, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lezak, M.; Howieson, D.; Loring, D.; Fischer, J. Neuropsychological Assessment; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss, E.; Sherman, E.; Spreen, O. A Compendium of Neuropsychological Tests: Administration, Norms and Commentary; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Peduzzi, P.; Concato, J.; Feinstein, A.R.; Holford, T.R. Importance of Events per Independent Variable in Proportional Hazards Regression Analysis. II. Accuracy and Precision of Regression Estimates. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 1995, 48, 1503–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panel on Prevention of Falls in Older Persons, American Geriatrics Society and British Geriatrics Society. Summary of the Updated American Geriatrics Society/British Geriatrics Society Clinical Practice Guideline for Prevention of Falls in Older Persons: Ags/Bgs Clinical Practice Guideline for Prevention of Falls. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2011, 59, 148–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bjerk, M.; Brovold, T.; Skelton, D.A.; Bergland, A. Associations between Health-Related Quality of Life, Physical Function and Fear of Falling in Older Fallers Receiving Home Care. BMC Geriatr. 2018, 18, 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.-M.; Chen, C.-M. Factors Associated with Quality of Life among Older Adults with Chronic Disease in Taiwan. Int. J. Gerontol. 2017, 11, 12–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kressig, R.W.; Wolf, S.L.; Sattin, R.W.; O’Grady, M.; Greenspan, A.; Curns, A.; Kutner, M. Associations of Demographic, Functional, and Behavioral Characteristics with Activity-Related Fear of Falling among Older Adults Transitioning to Frailty. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2001, 49, 1456–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamberlin, M.E.; Fulwider, B.D.; Sanders, S.L.; Medeiros, J.M. Does Fear of Falling Influence Spatial and Temporal Gait Parameters in Elderly Persons beyond Changes Associated with Normal Aging? J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2005, 60, 1163–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiedemann, A.; Sherrington, C.; Lord, S.R. Physiological and Psychological Predictors of Walking Speed in Older Community-Dwelling People. Gerontology 2005, 51, 390–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duque, G.; Boersma, D.; Loza-Diaz, G.; Hassan, S.; Suarez, H.; Geisinger, D.; Suriyaarachchi, P.; Sharma, A.; Demontiero, O. Effects of Balance Training Using a Virtual-Reality System in Older Fallers. Clin. Interv. Aging 2013, 8, 257–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Rodríguez-Molinero, A.; Herrero-Larrea, A.; Miñarro, A.; Narvaiza, L.; Gálvez-Barrón, C.; Gonzalo León, N.; Valldosera, E.; de Mingo, E.; Macho, O.; Aivar, D.; et al. The Spatial Parameters of Gait and Their Association with Falls, Functional Decline and Death in Older Adults: A Prospective Study. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 8813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mademli, L.; Arampatzis, A. Lower Safety Factor for Old Adults during Walking at Preferred Velocity. Age (Dordrecht) 2014, 36, 9636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryg, J.; Masud, T.; Lindholm Eriksen, M.; Vestergaard, S.; Andersen-Ranberg, K. Fear of Falling Is Associated with Decreased Grip Strength, Slower Walking Speed and Inability to Stand from Chair without Using Arms in a Large European Ageing Study. Eur. Geriatr. Med. 2012, 3, S1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, N.; Devine, A.; Dick, I.; Prince, R.; Bruce, D. Fear of Falling in Older Women: A Longitudinal Study of Incidence, Persistence, and Predictors: Predictors of Fear of Falling. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2007, 55, 1598–1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uemura, K.; Shimada, H.; Makizako, H.; Doi, T.; Tsutsumimoto, K.; Lee, S.; Umegaki, H.; Kuzuya, M.; Suzuki, T. Effects of Mild Cognitive Impairment on the Development of Fear of Falling in Older Adults: A Prospective Cohort Study. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2015, 16, 1104.e9–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirooka, H.; Nishiguchi, S.; Fukutani, N.; Tashiro, Y.; Nozaki, Y.; Hirata, H.; Yamaguchi, M.; Tasaka, S.; Matsushita, T.; Matsubara, K.; et al. Cognitive Impairment Is Associated with the Absence of Fear of Falling in Community-Dwelling Frail Older Adults. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2017, 17, 232–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peeters, G.; Leahy, S.; Kennelly, S.; Kenny, R.A. Is fear of falling associated with decline in global cognitive functioning in older adults: Findings from the Irish longitudinal study on ageing. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2018, 19, 248–254.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Values Total = 115 | Values | Men = 37 | Values | Women = 78 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 70.33 | 8.16 | 71.94 | 8.59 | 69.56 | 7.89 | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 29.34 | 5.03 | 29.09 | 3.63 | 29.46 | 5.60 | |

| Educational status , n (%) | No formal education | 16 | 13.92 | 4 | 10.82 | 12 | 15.38 |

| Primary education | 71 | 61.74 | 28 | 75.67 | 43 | 55.12 | |

| Secondary education | 23 | 20 | 4 | 10.82 | 19 | 24.35 | |

| University | 5 | 4.34 | 1 | 2.69 | 4 | 5.14 | |

| S-COWA (words) | 28.35 | 10.83 | 29.94 | 13.98 | 27.60 | 8.98 | |

| P-COWA (words) | 32.07 | 12.08 | 30.75 | 13.97 | 32.70 | 11.11 | |

| Step length (cm) | 56.29 | 12.83 | 56.24 | 14.24 | 56.32 | 12.19 | |

| Double support (s) | 0.31 | 0.15 | 0.33 | 0.14 | 0.30 | 0.16 | |

| Step time (s) | 0.47 | 0.21 | 0.48 | 0.18 | 0.47 | 0.21 | |

| Stride length (cm) | 112.67 | 25.36 | 112.78 | 28.92 | 112.62 | 24.05 | |

| Gait speed (m/s) | 1.11 | 1.46 | 0.89 | 0.21 | 1.21 | 1.76 | |

| Aceleration (s) | 0.02 | 0.22 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.27 | |

| Distance (cm) | 3704.37 | 6596.85 | 2952.67 | 525.82 | 4060.94 | 7993.75 | |

| Handgrip strength (kg) | 23.24 | 8.51 | 31.28 | 9.07 | 19.43 | 4.78 | |

| Chair Stand (s) | 14.32 | 4.92 | 13.92 | 5.40 | 14.53 | 4.70 | |

| FES-I score | 24.68 | 8.09 | 24.64 | 8.95 | 24.70 | 7.72 | |

| FES Score (s) | |

|---|---|

| S COWA | −0.229 1 |

| P COWA | −0.188 1 |

| Step length | 0.222 1 |

| Double support | 0.001 |

| Step time | 0.109 |

| Stride length | 0.222 1 |

| Gait speed | 0.043 |

| Acceleration | 0.005 |

| Distance | 0.994 |

| Handgrip strength | −0.075 |

| Chair Stand | 0.481 1 |

| Sex | 0.003 |

| Educational Status | −0.178 |

| Age (years) | 0.016 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 0.143 |

| Variable | B | β | t | 95% CI | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FES score (s) | S COWA | −0.180 | −0.241 | −2.459 | −0.325 | −0.035 | 0.015 |

| P COWA | −0.158 | −0.235 | −2.233 | −0.297 | −0.018 | 0.028 | |

| Chair Stand | 0.793 | 0.482 | 5.604 | 0.513 | 1.073 | 0.000 | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Orihuela-Espejo, A.; Álvarez-Salvago, F.; Martínez-Amat, A.; Boquete-Pumar, C.; De Diego-Moreno, M.; García-Sillero, M.; Aibar-Almazán, A.; Jiménez-García, J.D. Associations between Muscle Strength, Physical Performance and Cognitive Impairment with Fear of Falling among Older Adults Aged ≥ 60 Years: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10504. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191710504

Orihuela-Espejo A, Álvarez-Salvago F, Martínez-Amat A, Boquete-Pumar C, De Diego-Moreno M, García-Sillero M, Aibar-Almazán A, Jiménez-García JD. Associations between Muscle Strength, Physical Performance and Cognitive Impairment with Fear of Falling among Older Adults Aged ≥ 60 Years: A Cross-Sectional Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(17):10504. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191710504

Chicago/Turabian StyleOrihuela-Espejo, Antonio, Francisco Álvarez-Salvago, Antonio Martínez-Amat, Carmen Boquete-Pumar, Manuel De Diego-Moreno, Manuel García-Sillero, Agustín Aibar-Almazán, and José Daniel Jiménez-García. 2022. "Associations between Muscle Strength, Physical Performance and Cognitive Impairment with Fear of Falling among Older Adults Aged ≥ 60 Years: A Cross-Sectional Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 17: 10504. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191710504

APA StyleOrihuela-Espejo, A., Álvarez-Salvago, F., Martínez-Amat, A., Boquete-Pumar, C., De Diego-Moreno, M., García-Sillero, M., Aibar-Almazán, A., & Jiménez-García, J. D. (2022). Associations between Muscle Strength, Physical Performance and Cognitive Impairment with Fear of Falling among Older Adults Aged ≥ 60 Years: A Cross-Sectional Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(17), 10504. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191710504