Workplace Bullying and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Symptomology: The Influence of Role Conflict and the Moderating Effects of Neuroticism and Managerial Competencies

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Design and Procedure

3.2. Participants

3.3. Measures

3.3.1. Role Conflict

3.3.2. Exposure to Workplace Bullying

3.3.3. PTSD Symptomology

3.3.4. Managerial Competencies

3.3.5. Neuroticism

3.4. Data Analysis

4. Results

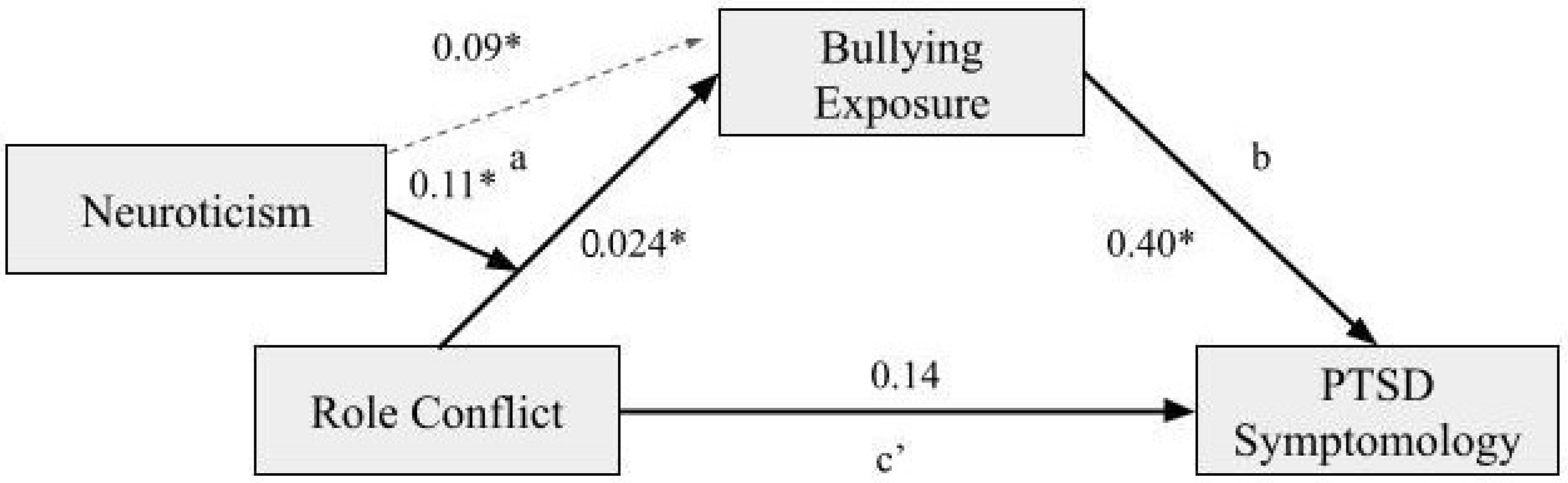

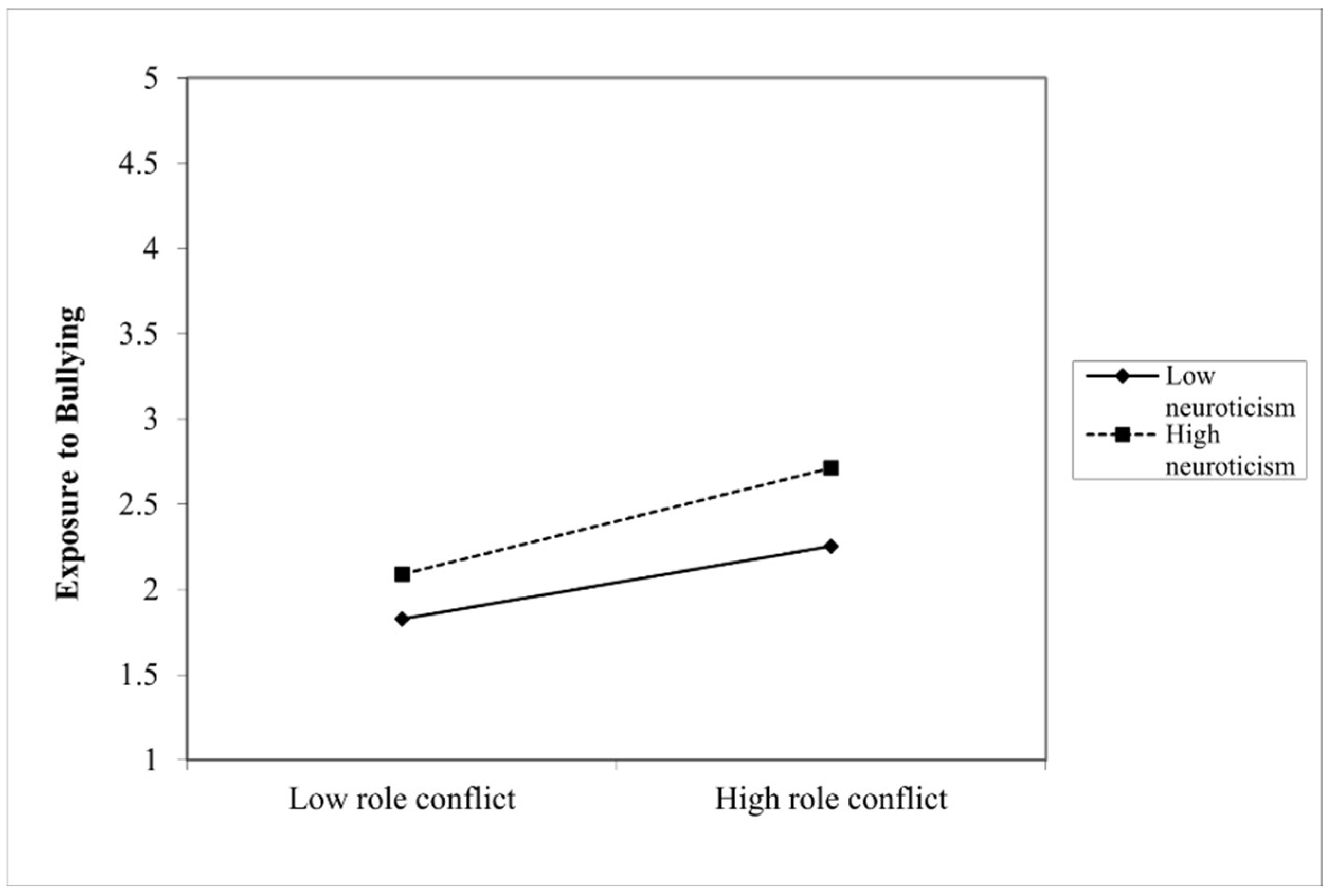

4.1. Moderated Mediation with the Moderator of Neuroticism

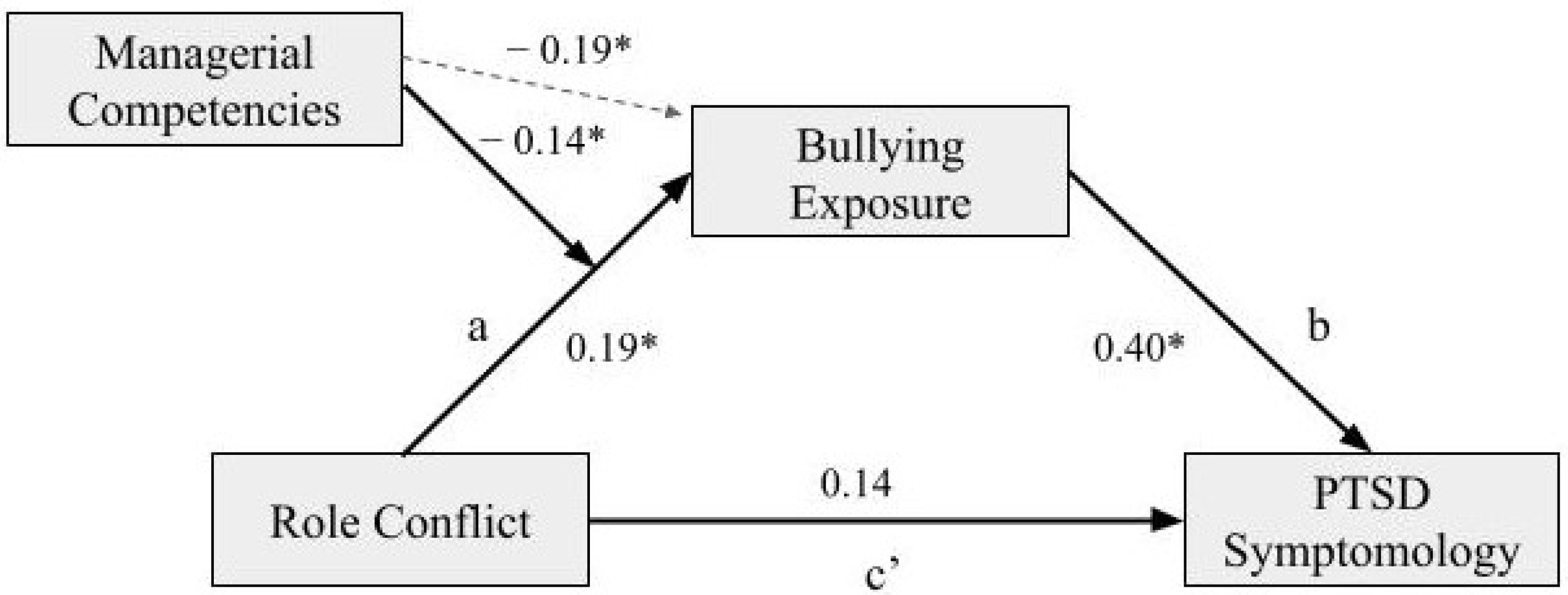

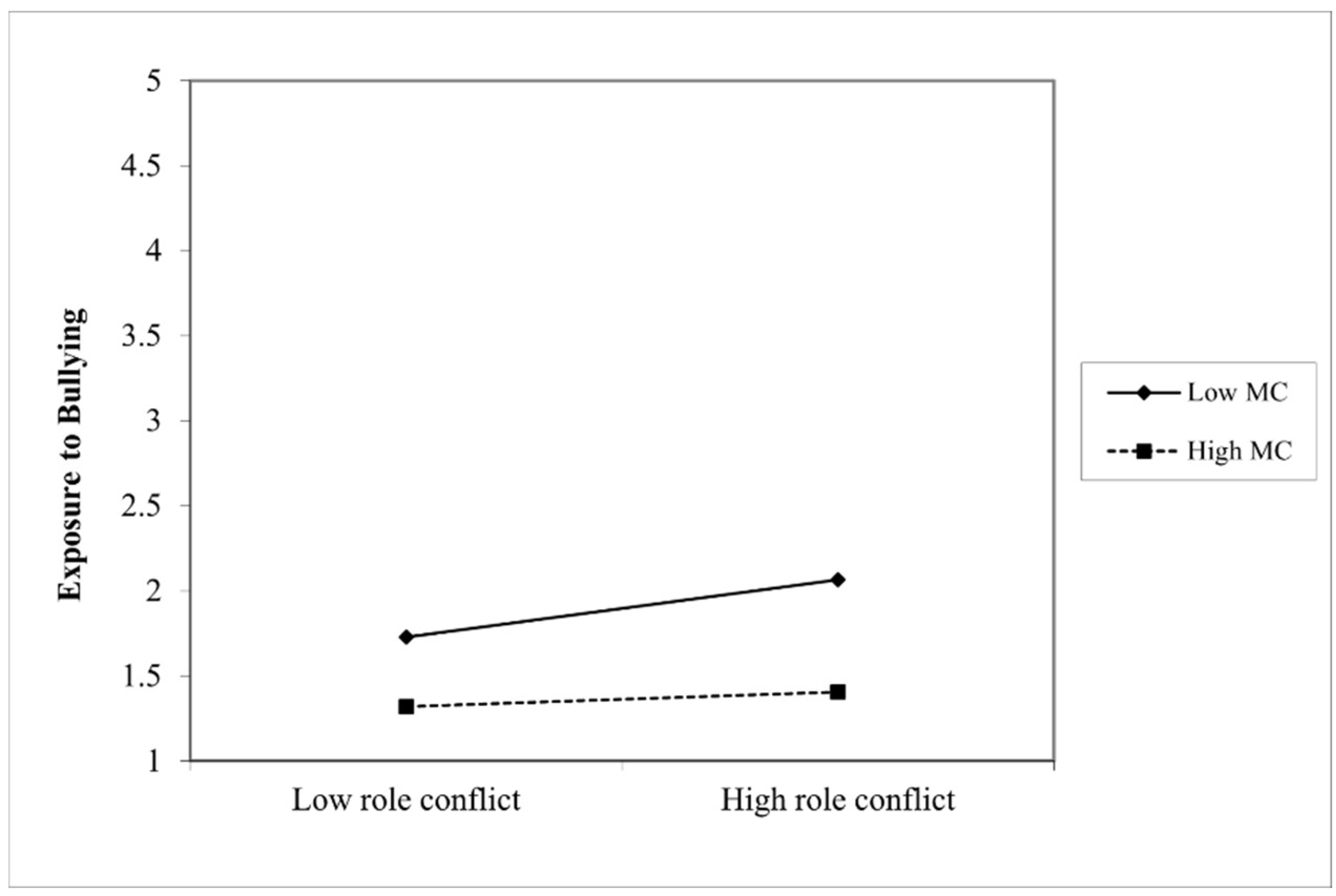

4.2. Moderated Mediation with Managerial Competencies as the Moderator

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

6.1. Practical Implications

6.2. Limitations

6.3. Future Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Items | Factor Loadings |

|---|---|

| Role Conflict | |

| 0.32 |

| 0.54 |

| 0.80 |

| 0.76 |

| 0.75 |

| Neuroticism | |

| 0.80 |

| 0.76 |

| 0.75 |

| 0.64 |

| PTSD Symptomology | |

| 0.81 |

| 0.93 |

| 0.52 |

| 0.62 |

| Exposure to Bullying | |

| 0.65 |

| 0.50 |

| 0.74 |

| 0.79 |

| 0.59 |

| 0.76 |

| 0.72 |

| 0.69 |

| 0.59 |

| Managerial Competencies | |

| 0.45 |

| 0.85 |

| 0.70 |

| 0.80 |

| 0.78 |

| 0.78 |

| 0.77 |

| 0.81 |

| 0.76 |

References

- Aluede, O.; Adeleke, F.; Omoike, D.; Afen-Akpaida, J. A review of the extent, nature, characteristics and effects of bullying behaviour in schools. J. Instruct. Psychol. 2008, 35, 151–158. Available online: https://search.proquest.com/scholarlyjournals/review-extent-nature-characteristics-effects/docview/213916211/se2?accountid=9652 (accessed on 22 April 2021).

- Einarsen, S. Relationships between exposure to bullying at work and psychological and psychosomatic health complaintsHarassment and bullying at work: A review of the Scandinavian approach. Aggress. Violent Behavior. 2000, 5, 379–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milczarek, M. Workplace Violence and Harassment: A European Picture; European Agency for Safety and Health at Work: EUROPEAN RISK OBSERVATORY REPORT, Ed.; UTB: Luxembourg, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giaccone, M.; Di Nunzio, D.; Fromm, A.; Vargas, O. Violence and Harassment in European Workplaces: Causes, Impacts and Policies; Eurofound: Dublin, Ireland, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Robinson, B. New Study Says Workplace Bullying on Rise: What You Can Do during National Bullying Prevention Month. Forbes. 15 October 2019. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/bryanrobinson/2019/10/11/new-study-says-workplacebullying-on-rise-what-can-you-do-during-national-bullying-preventionmonth/?sh=6ef724ca2a0d (accessed on 19 August 2022).

- Giga, S.I.; Hoel, H.; Lewis, D. The Costs of Workplace Bullying. Dignity at Work Partnership. 2008. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/260246863_The_Costs_of_Workplace_Bullying (accessed on 14 June 2022).

- Felber, J. Council Post: The Importance of Creativity in Business. Forbes. 14 April 2022. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/forbesbusinesscouncil/2020/08/18/the-importance-ofcreativity-in-business/?sh=778bce22e7d7 (accessed on 14 June 2022).

- Jiang, W.; Gu, Q.; Tang, T.L.P. Do Victims of Supervisor Bullying Suffer from Poor Creativity? Social Cognitive and Social Comparison Perspectives. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 157, 865–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillen, P.A.; Sinclair, M.; Kernohan, W.G.; Begley, C.M.; Luyben, A.G. Interventions for prevention of bullying in the Workplace. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 2017, CD009778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saam, N.J. Interventions in workplace bullying: A multilevel approach. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2010, 19, 51–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemp, V. Antecedents, consequences and interventions for workplace bullying. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2014, 27, 364–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, K.; Abildgaard, J.S. Organizational interventions: A research-based framework for the evaluation of both process and effects. Work Stress 2013, 27, 278–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Einarsen, S.V.; Hoel, H.; Zapf, D.; Cooper, C.L. The concept of bullying and harassment at work: The European tradition. In Bullying and Harassment in the Workplace: Theory, Research and Practice; Einarsen, S.V., Hoel, H., Zapf, D., Cooper, C.L., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2020; pp. 3–53. ISBN 0429462522. [Google Scholar]

- Notelaers, G.; Van Der Heijden, B.; Hoel, H.; Einarsen, S. Measuring bullying at work with the short-negative acts questionnaire: Identification of targets and criterion validity. Work Stress 2018, 33, 58–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conway, P.M.; Høgh, A.; Balducci, C.; Ebbesen, D.K. Workplace Bullying and Mental Health. In Pathways of Job-Related Negative Behaviour; D’Cruz, P., Noronha, E., Baillien, E., Catley, B., Harlos, K., Hogh, A., Mikkelsen, E.G., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2021; pp. 101–128. [Google Scholar]

- Høgh, A.; Clausen, T.; Bickmann, L.; Hansen, Å.M.; Conway, P.M.; Baernholdt, M. Consequences of Workplace Bullying for Individuals, Organizations and Society. In Pathways of Job-Related Negative Behaviour; D’Cruz, P., Noronha, E., Baillien, E., Catley, B., Harlos, K., Hogh, A., Mikkelsen, E.G., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2021; pp. 177–200. [Google Scholar]

- Hogh, A.; Mikkelsen, E.; Hansen, Å. Individual Consequences of Workplace Bullying/Mobbing. In Bullying and Harassment in the Workplace—Theory, Research and Practice; Einarsen, S.V., Hoel, H., Zapf, D., Cooper, C.L., Eds.; CRC Press: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 107–128. [Google Scholar]

- Burr, H.; Balducci, C.; Conway, P.M.; Rose, U. Workplace Bullying and Long-Term Sickness Absence—A Five-Year Follow-Up Study of 2476 Employees Aged 31 to 60 Years in Germany. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 7193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. ICD-11: International Classification of Diseases, 11th ed.; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. Available online: https://icd.who.int/ (accessed on 19 August 2022).

- Menghini, L.; Balducci, C. The Importance of Contextualized Psychosocial Risk Indicators in Workplace Stress Assessment: Evidence from the Healthcare Sector. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carver, C.S.; Connor-Smith, J. Personality and Coping. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2010, 61, 679–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colligan, T.W.; Higgins, E.M. Workplace Stress. J. Work. Behav. Health 2006, 21, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truxillo, D.M.; Bauer, T.N.; Erdogan, B. Psychology and Work: Perspectives on Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 1st ed.; New York, NY, USA, 2016; Available online: https://www.routledge.com/Psychology-and-Work-Perspectives-on-Industrial-and-Organizational-Psychology/Truxillo-Bauer-Erdogan/p/book/9781848725089?gclid=CjwKCAjwmJeYBhAwEiwAXlg0AfkphEO2KwaJQE1nF3_c6CAzIXiCZtLcJTyF0edn8kEqGwL5cKMdiRoCU5IQAvD_BwE (accessed on 14 June 2022).

- Hecht, L.M. Role Conflict and Role Overload: Different Concepts, Different Consequences. Sociol. Inq. 2001, 71, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balducci, C.; Conway, P.M.; van Heugten, K. The Contribution of Organizational Factors to Workplace Bullying, Emotional Abuse and Harassment. In Handbooks of Workplace Bullying, Emotional Abuse and Harassment, Pathways of Job-Related Negative Behaviour; D’Cruz, P., Noronha, E., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2018; Volume 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauge, L.J.; Skogstad, A.; Einarsen, S. Relationships between stressful work environments and bullying: Results of a large representative study. Work Stress 2007, 21, 220–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Notelaers, G.; De Witte, H.; Einarsen, S. A job characteristics approach to explain workplace bullying. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2010, 19, 487–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Brande, W.; Baillien, E.; De Witte, H.; Elst, T.V.; Godderis, L. The role of work stressors, coping strategies and coping resources in the process of workplace bullying: A systematic review and development of a comprehensive model. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2016, 29, 61–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadal, K.L. Microaggressions and Traumatic Stress: Theory, Research, and Clinical Treatment; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research. Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). Mayo Clinic. 6 July 2018. Available online: https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/post-traumatic-stressdisorder/symptoms-causes/syc-20355967#:~:text=Intrusive%20memories,-Symptoms%20of%20intrusive&text=Reliving%20the%20traumatic%20event%20as,you%20of%20the%20traumatic%20event (accessed on 14 June 2022).

- Balducci, C.; Alfano, V.; Fraccaroli, F. Relationships Between Mobbing at Work and MMPI-2 Personality Profile, Posttraumatic Stress Symptoms, and Suicidal Ideation and Behavior. Violence Vict. 2009, 24, 52–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, M.B.; Tangen, T.; Idsoe, T.; Matthiesen, S.B.; Magerøy, N. Post-traumatic stress disorder as a consequence of bullying at work and at school. A literature review and meta-analysis. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2015, 21, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikkelsen, E.G.; Einarsen, S. Relationships between exposure to bullying at work and psychological and psychosomatic health complaints: The role of state negative affectivity and generalized self–efficacy. Scand. J. Psychol. 2002, 43, 397–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zapf, D.; Einarsen, S.V. Individual Antecedents of Bullying: Personality, Motives and Competencies of Victims and Perpetrators. In Bullying and Harassment in the Workplace: Theory, Research and Practice; Einarsen, S.V., Hoel, H., Zapf, D., Cooper, C.L., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2020; pp. 269–303. ISBN 0429462522. [Google Scholar]

- Sur, S.; Ng, E. Extending Theory on Job Stress. Hum. Resour. Dev. Rev. 2014, 13, 79–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blum, S.; Brow, M. Coping. In Encyclopedia of Human Behavior, 2nd ed.; Silver, R.C., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2012; pp. 596–601. [Google Scholar]

- Abbasi, I.S. The Role of Neuroticism in the Maintenance of Chronic Baseline Stress Perception and Negative Affect. Span. J. Psychol. 2016, 19, E9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toderi, S.; Balducci, C. Stress-Preventive Management Competencies, Psychosocial Work Environments, and Affective Well-Being: A Multilevel, Multisource Investigation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzo, J.R.; House, R.J.; Lirtzman, S.I. Role Conflict and Ambiguity in Complex Organizations. Adm. Sci. Q. 1970, 15, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balducci, C.; Cecchin, M.; Fraccaroli, F. A longitudinal analysis of the relationship between role stressors and workplace bullying including personal vulnerability factors. Work Stress 2012, 26, 195–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balducci, C.; Spagnoli, P.; Alfano, V.; Barattucci, M.; Notelaers, G.; Fraccaroli, F. Valutare il rischio mobbing nelle organizzazioni: Contributo alla validazione Italiana dello Short Negative Acts Questionnaire (S-NAQ) [Assessing the mobbing risk in organizations: Contribution to the Italian validation of the Short Negative Acts Questionnaire (S-NAQ)]. Psicol. Soc. 2010, 5, 147–167. [Google Scholar]

- Lang, A.J.; Stein, M.B. An abbreviated PTSD checklist for use as a screening instrument in primary care. Behav. Res. Ther. 2005, 43, 585–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toderi, S.; Sarchielli, G. Psychometric Properties of a 36-Item Version of the “Stress Management Competency Indicator Tool”. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2016, 13, 1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, L.R. The development of markers for the Big-Five factor structure. Psychol. Assess. 1992, 4, 26–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flebus, G.B. Versione Italiana dei Big Five Markers di Goldberg. 2006; Unpublished Manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Balducci, C.; Alessandri, G.; Zaniboni, S.; Avanzi, L.; Borgogni, L.; Fraccaroli, F. The impact of workaholism on day-level workload and emotional exhaustion, and on longer-term job performance. Work Stress 2020, 35, 6–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boudrias, V.; Trépanier, S.-G.; Salin, D. A systematic review of research on the longitudinal consequences of workplace bullying and the mechanisms involved. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2021, 56, 101508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conway, P.M.; Burr, H.; Rose, U.; Clausen, T.; Balducci, C. Antecedents of Workplace Bullying among Employees in Germany: Five-Year Lagged Effects of Job Demands and Job Resources. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 10805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özer, G.; Griep, Y.; Escartín, J. The Relationship between Organizational Environment and Perpetrators’ Physical and Psychological State: A Three-Wave Longitudinal Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balducci, C.; Menghini, L.; Conway, P.M.; Burr, H.; Zaniboni, S. Workaholism and the Enactment of Bullying Behavior at Work: A Prospective Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baillien, E.; Salin, D.; Bastiaensen, C.V.M.; Notelaers, G. High Performance Work Systems, Justice, and Engagement: Does Bullying Throw a Spanner in the Works? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 5583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedeian, A.G.; Armenakis, A.A. A Path-Analytic Study of the Consequences of Role Conflict and Ambiguity. Acad. Manag. J. 1981, 24, 417–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Decuypere, A.; Audenaert, M.; Decramer, A. When mindfulness interacts with neuroticism to enhance transformational leadership: The role of Psychological Need Satisfaction. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varghese, L.S.; Rogers, A.P.; Finkelstein, L.; Barber, L.K. Examining mentors as buffers of burnout for employees high in neuroticism. Hum. Resour. Dev. Q. 2020, 31, 281–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuttleworth, A. Managing workplace stress: How training can help. Ind. Commer. Train. 2004, 36, 61–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viswesvaran, C.; Sanchez, J.I.; Fisher, J. The Role of Social Support in the Process of Work Stress: A Meta-Analysis. J. Vocat. Behav. 1999, 54, 314–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wichert, I.; Burchell, B.; Ladipo, D.; Wilkinson, F. Stress intervention: What can managers do? In Job Insecurity and Work Intensification; Routledge, 2001; pp. 154–161. Available online: https://www.routledge.com/Job-Insecurity-and-Work-Intensification/Burchell-Ladipo-Wilkinson/p/book/9780415236539 (accessed on 14 June 2022).

- Keys, B.J. The Management of Learning Grid for Management Development Revisited. J. Manag. Dev. 1989, 8, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.; Dickson, D.R. A Case Study into the Benefits of Management Training Programs: Impacts on Hotel Employee Turnover and Satisfaction Level. J. Hum. Resour. Hosp. Tour. 2009, 9, 103–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bass, B.M.; Avolio, B.J. Developing Transformational Leadership: 1992 and Beyond. J. Eur. Ind. Train. 1990, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, A.S.; Flaschner, A.B.; Shachar, M. Mitigating stress and burnout by implementing transformational-leadership. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2006, 18, 469–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, M.B.; Einarsen, S.V. What we know, what we do not know, and what we should and could have known about workplace bullying: An overview of the literature and agenda for future research. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2018, 42, 71–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, M.F.; Zapf, D.; Winefield, H.; Sarris, A. Bullying allegations from the accused bully’s perspective. Br. J. Manag. 2012, 23, 489–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balducci, C.; Schaufeli, W.B.; Fraccaroli, F. The job demands–resources model and counterproductive work behaviour: The role of job-related affect. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2011, 20, 467–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spector, P.E. Do Not Cross Me: Optimizing the Use of Cross-Sectional Designs. J. Bus. Psychol. 2019, 34, 125–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleury, J.; Keller, C.; Perez, A. Social Support Theoretical Perspective. Geriatr. Nurs. 2009, 30, 11–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, K.; Niven, K.; Notelaers, G. Does bystander behavior make a difference? How passive and active bystanders in the group moderate the effects of bullying exposure. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2021, 27, 119–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Role conflict | 2.46 | 0.89 | ||||

| 2. Bullying exposure | 1.47 | 0.48 | 0.48 ** | |||

| [0.38, 0.57] | ||||||

| 3. PTSD symptomology | 2.06 | 0.91 | 0.24 ** | 0.28 ** | ||

| [0.08, 0.38] | [0.12, 0.43] | |||||

| 4. Neuroticism | 2.45 | 0.86 | 0.19 * | 0.23 ** | 0.32 ** | |

| [0.04, 0.34] | [0.10, 0.36] | [0.17, 0.45] | ||||

| 5. Managerial competencies | 3.35 | 0.82 | −0.31 ** | −0.43 ** | −0.15 | −0.40 ** |

| [−0.46, −0.15] | [−0.55, 0.30] | [− 0.31, 0.04] | [−0.52, −0.28] |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chenevert, M.; Vignoli, M.; Conway, P.M.; Balducci, C. Workplace Bullying and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Symptomology: The Influence of Role Conflict and the Moderating Effects of Neuroticism and Managerial Competencies. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10646. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191710646

Chenevert M, Vignoli M, Conway PM, Balducci C. Workplace Bullying and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Symptomology: The Influence of Role Conflict and the Moderating Effects of Neuroticism and Managerial Competencies. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(17):10646. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191710646

Chicago/Turabian StyleChenevert, Miren, Michela Vignoli, Paul M. Conway, and Cristian Balducci. 2022. "Workplace Bullying and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Symptomology: The Influence of Role Conflict and the Moderating Effects of Neuroticism and Managerial Competencies" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 17: 10646. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191710646

APA StyleChenevert, M., Vignoli, M., Conway, P. M., & Balducci, C. (2022). Workplace Bullying and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Symptomology: The Influence of Role Conflict and the Moderating Effects of Neuroticism and Managerial Competencies. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(17), 10646. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191710646