Moving Back to the Parental Home in Times of COVID-19: Consequences for Students’ Life Satisfaction

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Returning to the Parental Home

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Sample

3.2. Measures

3.3. Statistical Approach

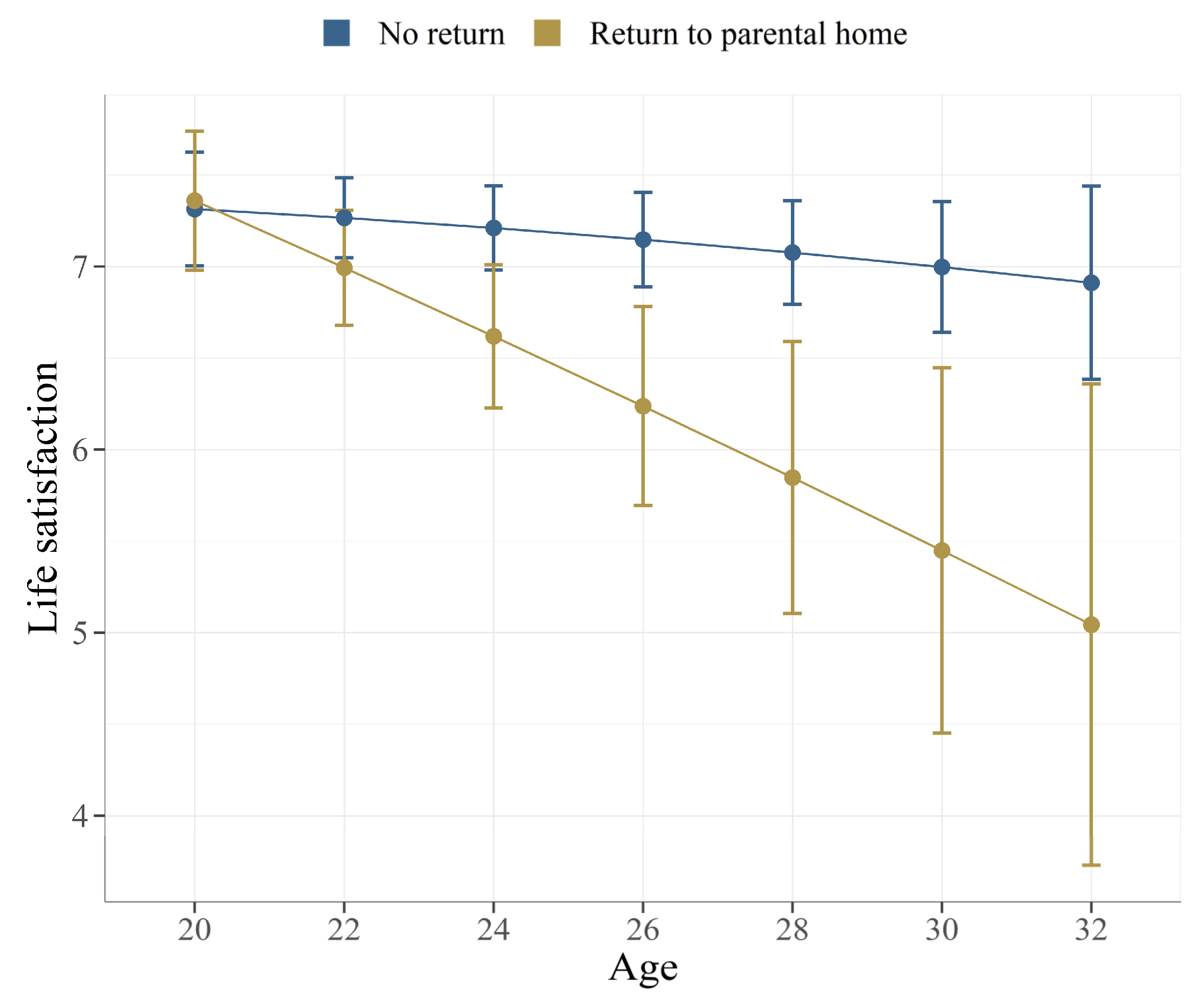

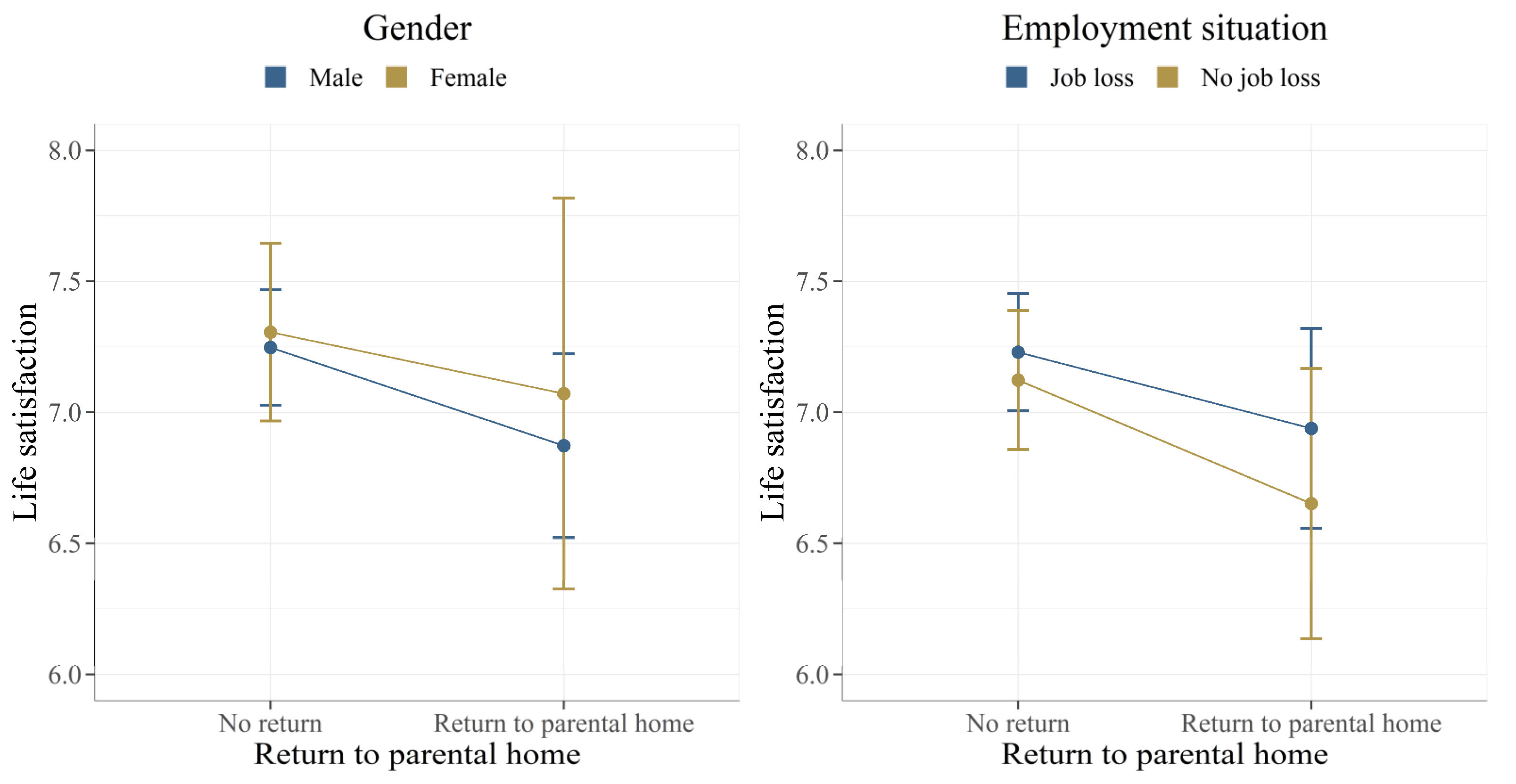

4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cao, W.; Fang, Z.; Hou, G.; Han, M.; Xu, X.; Dong, J.; Zheng, J. The Psychological Impact of the COVID-19 Epidemic on College Students in China. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 287, 112934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daly, M.; Sutin, A.R.; Robinson, E. Longitudinal Changes in Mental Health and the COVID-19 Pandemic: Evidence from the UK Household Longitudinal Study. Psychol. Med. 2020, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fried, E.I.; Papanikolaou, F.; Epskamp, S. Mental Health and Social Contact During the COVID-19 Pandemic: An Ecological Momentary Assessment Study. Clin. Psychol. Sci. 2022, 10, 340–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satici, B.; Gocet-Tekin, E.; Deniz, M.E.; Satici, S.A. Adaptation of the Fear of COVID-19 Scale: Its Association with Psychological Distress and Life Satisfaction in Turkey. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2021, 19, 1980–1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Zhao, H. The Impact of COVID-19 on Anxiety in Chinese University Students. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gambin, M.; Sękowski, M.; Woźniak-Prus, M.; Wnuk, A.; Oleksy, T.; Cudo, A.; Hansen, K.; Huflejt-Łukasik, M.; Kubicka, K.; Łyś, A.E.; et al. Generalized Anxiety and Depressive Symptoms in Various Age Groups during the COVID-19 Lockdown in Poland. Specific Predictors and Differences in Symptoms Severity. Compr. Psychiatry 2021, 105, 152222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Zhao, N. Generalized Anxiety Disorder, Depressive Symptoms and Sleep Quality during COVID-19 Outbreak in China: A Web-Based Cross-Sectional Survey. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 288, 112954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, U.; Klaas, H.S.; Antal, E.; Dasoki, N.; Lebert, F.; Lipps, O.; Monsch, G.-A.; Refle, J.-E.; Ryser, V.-A.; Tillmann, R.; et al. Who Is Most Affected by the Corona Crisis? An Analysis of Changes in Stress and Well-Being in Switzerland. Eur. Soc. 2021, 23, 942–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierce, M.; Hope, H.; Ford, T.; Hatch, S.; Hotopf, M.; John, A.; Kontopantelis, E.; Webb, R.; Wessely, S.; McManus, S.; et al. Mental Health before and during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Longitudinal Probability Sample Survey of the UK Population. Lancet Psychiatry 2020, 7, 883–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varma, P.; Junge, M.; Meaklim, H.; Jackson, M.L. Younger People Are More Vulnerable to Stress, Anxiety and Depression during COVID-19 Pandemic: A Global Cross-Sectional Survey. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2021, 109, 110236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, J.; Butler-Henderson, K.; Rudolph, J.; Malkawi, B.; Glowatz, M.; Burton, R.; Magni, P.; Lam, S. COVID-19: 20 Countries’ Higher Education Intra-Period Digital Pedagogy Responses. J. Appl. Learn. Teach. 2020, 3, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halliburton, A.E.; Hill, M.B.; Dawson, B.L.; Hightower, J.M.; Rueden, H. Increased Stress, Declining Mental Health: Emerging Adults’ Experiences in College During COVID-19. Emerg. Adulthood 2021, 9, 433–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aristovnik, A.; Keržič, D.; Ravšelj, D.; Tomaževič, N.; Umek, L. Impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Life of Higher Education Students: A Global Perspective. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, Y.; Du, X. Addressing Collegiate Mental Health amid COVID-19 Pandemic. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 288, 113003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aucejo, E.M.; French, J.; Ugalde Araya, M.P.; Zafar, B. The Impact of COVID-19 on Student Experiences and Expectations: Evidence from a Survey. J. Public Econ. 2020, 191, 104271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmer, T.; Mepham, K.; Stadtfeld, C. Students under Lockdown: Comparisons of Students’ Social Networks and Mental Health before and during the COVID-19 Crisis in Switzerland. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0236337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copeland, W.E.; McGinnis, E.; Bai, Y.; Adams, Z.; Nardone, H.; Devadanam, V.; Rettew, J.; Hudziak, J.J. Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on College Student Mental Health and Wellness. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2021, 60, 134–141.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.; Zhou, F.; Hou, W.; Silver, Z.; Wong, C.Y.; Chang, O.; Drakos, A.; Zuo, Q.K.; Huang, E. The Prevalence of Depressive Symptoms, Anxiety Symptoms and Sleep Disturbance in Higher Education Students during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2021, 301, 113863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kujawa, A.; Green, H.; Compas, B.E.; Dickey, L.; Pegg, S. Exposure to COVID-19 Pandemic Stress: Associations with Depression and Anxiety in Emerging Adults in the United States. Depress. Anxiety 2020, 37, 1280–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meeter, M.; Bele, T.; den Hartogh, C.; Bakker, T.C.; de Vries, R.E.; Plak, S. College Students’ Motivation and Study Results after COVID-19 Stay-at-Home Orders. PsyArXiv 2020. Available online: https://psyarxiv.com/kn6v9 (accessed on 2 July 2022). [CrossRef]

- Ohannessian, C.M. Introduction to the Special Issue: The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Lives of Emerging Adults. Emerg. Adulthood 2021, 9, 431–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldscheider, F.; Goldscheider, C. The Changing Transition to Adulthood: Leaving and Returning Home; SAGE Publications: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1999; ISBN 978-1-4522-6511-7. [Google Scholar]

- Houle, J.N.; Warner, C. Into the Red and Back to the Nest? Student Debt, College Completion, and Returning to the Parental Home among Young Adults. Sociol. Educ. 2017, 90, 89–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sironi, M.; Furstenberg, F.F. Trends in the Economic Independence of Young Adults in the United States: 1973–2007. Popul. Dev. Rev. 2012, 38, 609–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benson, J.E.; Furstenberg, F.F. Entry into Adulthood: Are Adult Role Transitions Meaningful Markers of Adult Identity? Adv. Life Course Res. 2006, 11, 199–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, S.S.; Zygmunt, E. “I Hate It Here”: Mental Health Changes of College Students Living with Parents During the COVID-19 Quarantine. Emerg. Adulthood 2021, 9, 449–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, L.J.; Barry, C.M. Distinguishing Features of Emerging Adulthood: The Role of Self-Classification as an Adult. J. Adolesc. Res. 2005, 20, 242–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunne, T. Household Formation and the Great Recession. Econ. Comment. 2012, 12, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.O.; Painter, G. What Happens to Household Formation in a Recession? J. Urban Econ. 2013, 76, 93–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lennartz, C.; Arundel, R.; Ronald, R. Younger Adults and Homeownership in Europe Through the Global Financial Crisis: Young People and Homeownership in Europe Through the GFC. Popul. Space Place 2016, 22, 823–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mykyta, L.; Macartney, S. The Effects of Recession on Household Composition: “Doubling Up” and Economic Well-Being; SEHSD Working Paper Series; U.S. Census Bureau: Suitland, MD, USA, 2011; p. 33.

- Middendorff, E.; Apolinarski, B.; Becker, K.; Bornkessel, P.; Brandt, T.; Heißenberg, S.; Poskowsky, J. Die Wirtschaftliche und Soziale Lage der Studierenden in Deutschland 2016. 21. Sozialerhebung des Deutschen Studentenwerksdurchgeführt vom Deutschen Zentrum für Hochschul- und Wissenschaftsforschung; Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung (BMBF): Bonn, Germany, 2017; p. 196.

- Becker, K.; Lörz, M. Studieren während der Corona-Pandemie: Die finanzielle Situation von Studierenden und mögliche Auswirkungen auf das Studium. DZHW Brief 2020, 9, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caputo, J. Parental Coresidence, Young Adult Role, Economic, and Health Changes, and Psychological Well-Being. Soc. Ment. Health 2020, 10, 199–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copp, J.E.; Giordano, P.C.; Longmore, M.A.; Manning, W.D. Living with Parents and Emerging Adults’ Depressive Symptoms. J. Fam. Issues 2017, 38, 2254–2276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, J.; Berrington, A.; Falkingham, J. Gender, Turning Points, and Boomerangs: Returning Home in Young Adulthood in Great Britain. Demography 2014, 51, 257–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharon, T. Constructing Adulthood: Markers of Adulthood and Well-Being Among Emerging Adults. Emerg. Adulthood 2016, 4, 161–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berngruber, A. The Timing of and Reasons Why Young People in Germany Return to Their Parental Home. J. Youth Stud. 2021, 24, 213–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- South, S.J.; Lei, L. Failures-to-Launch and Boomerang Kids: Contemporary Determinants of Leaving and Returning to the Parental Home. Soc. Forces 2015, 94, 863–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Berg, L.; Kalmijn, M.; Leopold, T. Leaving and Returning Home: A New Approach to Off-Time Transitions. J. Marriage Fam. 2019, 81, 679–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, D.N.F.; Blanchflower, D.G. US and UK Labour Markets before and during the COVID-19 Crash. NIER 2020, 252, R52–R69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruno, G.S.F.; Marelli, E.; Signorelli, M. The Rise of NEET and Youth Unemployment in EU Regions after the Crisis. Comp. Econ. Stud. 2014, 56, 592–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Churchill, B. COVID-19 and the Immediate Impact on Young People and Employment in Australia: A Gendered Analysis. Gend. Work. Organ. 2021, 28, 783–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsby, M.W.L.; Shin, D.; Solon, G. Wage Adjustment in the Great Recession and Other Downturns: Evidence from the United States and Great Britain. J. Labor Econ. 2016, 34, S249–S291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambovska, M.; Sardinha, B.; Belas, J., Jr. Impact of the Covid-19 Pandemic on Youth Unemployment in the European Union. EMS 2021, 15, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaeger, D.A.; Arellano-Bover, J.; Karbownik, K.; Martínez-Matute, M.; Nunley, J.; Seals, R.A.; Almunia, M.; Alston, M.; Becker, S.O.; Beneito, P.; et al. The Global COVID-19 Student Survey: First Wave Results; IZA Discussion Paper Series; IZA Institute of Labor Economics: Bonn, Germany, 2021; p. 171. [Google Scholar]

- Hawk, S.T.; Keijsers, L.; Hale, W.W., III; Meeus, W. Mind Your Own Business! Longitudinal Relations between Perceived Privacy Invasion and Adolescent-Parent Conflict. J. Fam. Psychol. 2009, 23, 511–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, K. The Boomerang Generation. Feeling OK about Living with Mom and Dad; PEW Social and Demographic Trends; Pew Research Center: Washington, DC, USA, 2012; p. 20. [Google Scholar]

- Sassler, S.; Ciambrone, D.; Benway, G. Are They Really Mama’s Boys/Daddy’s Girls? The Negotiation of Adulthood upon Returning to the Parental Home. Sociol. Forum 2008, 23, 670–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, R.A.; Spitze, G.D. Nestleaving and Coresidence by Young Adult Children: The Role of Family Relations. Res. Aging 2007, 29, 257–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busetta, G.; Campolo, M.G.; Fiorillo, F.; Pagani, L.; Panarello, D.; Augello, V. Effects of COVID-19 Lockdown on University Students’ Anxiety Disorder in Italy. Genus 2021, 77, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conrad, R.C.; Hahm, H.C.; Koire, A.; Pinder-Amaker, S.; Liu, C.H. College Student Mental Health Risks during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Implications of Campus Relocation. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2021, 136, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, A.L.; Carnrite, K.D.; Barker, E.T. First-Year University Students’ Mental Health Trajectories Were Disrupted at the Onset of COVID-19, but Disruptions Were Not Linked to Housing and Financial Vulnerabilities: A Registered Report. Emerg. Adulthood 2022, 10, 264–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preetz, R.; Filser, A.; Brömmelhaus, A.; Baalmann, T.; Feldhaus, M. Longitudinal Changes in Life Satisfaction and Mental Health in Emerging Adulthood during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Risk and Protective Factors. Emerg. Adulthood 2021, 9, 602–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drydakis, N. The Effect of Unemployment on Self-Reported Health and Mental Health in Greece from 2008 to 2013: A Longitudinal Study before and during the Financial Crisis. Soc. Sci. Med. 2015, 128, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gebel, M.; Voßemer, J. The Impact of Employment Transitions on Health in Germany. A Difference-in-Differences Propensity Score Matching Approach. Soc. Sci. Med. 2014, 108, 128–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richardson, T.; Elliott, P.; Roberts, R.; Jansen, M. A Longitudinal Study of Financial Difficulties and Mental Health in a National Sample of British Undergraduate Students. Community Ment. Health J. 2017, 53, 344–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vogl-Bauer, S. When the World Comes Home: Examining Internal and External Infl Uences on Communication Exchanges Between Parents and Their Boomerang Children. In Parents and Children Communicating with Society; Socha, T.J., Stamp, G., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 285–304. ISBN 978-0-203-93860-7. [Google Scholar]

- Graupensperger, S.; Jaffe, A.E.; Fleming, C.N.B.; Kilmer, J.R.; Lee, C.M.; Larimer, M.E. Changes in College Student Alcohol Use During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Are Perceived Drinking Norms Still Relevant? Emerg. Adulthood 2021, 9, 531–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diener, E.; Suh, E.M.; Lucas, R.E.; Smith, H.L. Subjective Well-Being: Three Decades of Progress. Psychol. Bull. 1999, 125, 276–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbeek, M. A Guide to Modern Econometrics, 3rd ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK; Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Woolridge, J.M. Econometric Analysis of Cross Section and Panel Data; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Dalgaard, P. Introductory Statistics with R; Statistics and Computing; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2008; ISBN 978-0-387-79053-4. [Google Scholar]

- Gohel, D. Flextable: Functions for Tabular Reporting; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Wickham, H.; Averick, M.; Bryan, J.; Chang, W.; McGowan, L.D.; François, R.; Grolemund, G.; Hayes, A.; Henry, L.; Hester, J.; et al. Welcome to the Tidyverse. J. Open Source Softw. 2019, 4, 1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, D.T.; Wade, M.; May, S.S.; Jenkins, J.M.; Prime, H. COVID-19 Disruption Gets inside the Family: A Two-Month Multilevel Study of Family Stress during the Pandemic. Dev. Psychol. 2021, 57, 1681–1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fong, V.C.; Iarocci, G. Child and Family Outcomes Following Pandemics: A Systematic Review and Recommendations on COVID-19 Policies. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2020, 45, 1124–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, S.S.; Zygmunt, E. Dislocated College Students and the Pandemic: Back Home Under Extraordinary Circumstances. Fam. Relat. 2021, 70, 689–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spinelli, M.; Lionetti, F.; Pastore, M.; Fasolo, M. Parents’ Stress and Children’s Psychological Problems in Families Facing the COVID-19 Outbreak in Italy. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boss, P. Family Stress Management: A Contextual Approach, 2nd ed.; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Boss, P. Resilience as Tolerance for Ambiguity. In Handbook of Family Resilience; Becvar, D.S., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 285–297. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, S.; Galambos, N.L.; Johnson, M.D. Parent–Child Contact, Closeness, and Conflict Across the Transition to Adulthood. J. Marriage Fam. 2021, 83, 1176–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parra, A.; Oliva, A.; Reina, M. del C. Family Relationships From Adolescence to Emerging Adulthood: A Longitudinal Study. J. Fam. Issues 2015, 36, 2002–2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berngruber, A. ‘Generation Boomerang’ in Germany? Returning to the Parental Home in Young Adulthood. J. Youth Stud. 2015, 18, 1274–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Schmidt-Klau, D.; Verick, S. The Labour Market Impacts of the COVID-19: A Global Perspective. Ind. J. Labour Econ. 2020, 63, 11–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, S.; Berg, J. The Labour Market Fallout of COVID-19: Who Endures, Who Doesn’t and What Are the Implications for Inequality. Int. Labour Rev. 2022, 161, 5–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fish, J.N.; McInroy, L.B.; Paceley, M.S.; Williams, N.D.; Henderson, S.; Levine, D.S.; Edsall, R.N. “I’m Kinda Stuck at Home with Unsupportive Parents Right Now”: LGBTQ Youths’ Experiences with COVID-19 and the Importance of Online Support. J. Adolesc. Health 2020, 67, 450–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowleg, L.; Landers, S. The Need for COVID-19 LGBTQ-Specific Data. Am. J. Public Health 2021, 111, 1604–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, K.D. Implications of the COVID-19 Pandemic on LGBTQ Communities. J. Public Health Manag. Pract. 2021, 27, S69–S71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halkitis, P.N.; Krause, K.D. COVID-19 in LGBTQ Populations. Ann. LGBTQ Public Popul. Health 2021, 1, 249–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salerno, J.P.; Devadas, J.; Pease, M.; Nketia, B.; Fish, J.N. Sexual and Gender Minority Stress Amid the COVID-19 Pandemic: Implications for LGBTQ Young Persons’ Mental Health and Well-Being. Public Health Rep. 2020, 135, 721–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salerno, J.P.; Doan, L.; Sayer, L.C.; Drotning, K.J.; Rinderknecht, R.G.; Fish, J.N. Changes in Mental Health and Well-Being Are Associated with Living Arrangements with Parents during COVID-19 among Sexual Minority Young Persons in the U.S. Psychol. Sex. Orientat. Gend. Divers. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anusic, I.; Yap, S.C.Y.; Lucas, R.E. Testing Set-Point Theory in a Swiss National Sample: Reaction and Adaptation to Major Life Events. Soc. Indic. Res. 2014, 119, 1265–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diener, E.; Lucas, R.E.; Scollon, C.N. Beyond the Hedonic Treadmill: Revising the Adaptation Theory of Well-Being. Am. Psychol. 2006, 61, 305–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preetz, R. Dissolution of Non-Cohabiting Relationships and Changes in Life Satisfaction and Mental Health. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 812831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | n | Mean or % | SD | Min | Max | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Life satisfaction | 913 | 7.11 | 2.048 | 1 | 10 | |

| Return to parental home | No return | 719 | 78.8% | |||

| Return to parental home | 194 | 21.2% | ||||

| Gender | Female | 721 | 79.0% | |||

| Male | 192 | 21.0% | ||||

| Employment situation | No change | 576 | 63.1% | |||

| Job loss | 337 | 36.9% | ||||

| Age | 913 | 23.75 | 3.207 | 18 | 35 |

| Variable | Life Satisfaction | Moving Back to Parental Home | Employment Situation | Gender |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Return to parental home (ref.: Did not move back) | −0.044 | |||

| [−0.109; 0.021] | ||||

| Employment situation: Job loss (ref.: No change) | −0.043 | −0.053 | ||

| [−0.107; 0.022] | [−0.118; 0.012] | |||

| Gender Male (ref.: Female) | 0.014 | −0.071 * | −0.038 | |

| [−0.051; 0.079] | [−0.135; −0.006] | [−0.103; 0.027] | ||

| Age | −0.071 * | −0.269 *** | 0.122 *** | 0.086 ** |

| [−0.135; −0.006] | [−0.328; −0.208] | [0.057; 0.185] | [0.021; 0.15] |

| Variable | B | SE | min95 | max95 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Return to parental home | No return to parental home | ref. | ||||

| Return to parental home | −0.352 * | 0.173 | −0.692 | −0.012 | 0.042 | |

| Employment situation | No change | ref. | ||||

| Job loss | −0.142 | 0.142 | −0.421 | 0.137 | 0.319 | |

| Age | Age | −0.191 | 0.251 | −0.684 | 0.301 | 0.446 |

| Age2 | 0.003 | 0.005 | −0.007 | 0.012 | 0.586 | |

| Gender | Female | ref. | ||||

| Male | 0.082 | 0.167 | −0.246 | 0.411 | 0.624 | |

| Intercept | 10.205 ** | 3.120 | 4.081 | 16.329 | 0.001 | |

| R2 | 0.011 | |||||

| adjusted R2 | 0.006 | |||||

| N | 913 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Preetz, R.; Greifenberg, J.; Hülsemann, J.; Filser, A. Moving Back to the Parental Home in Times of COVID-19: Consequences for Students’ Life Satisfaction. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10659. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191710659

Preetz R, Greifenberg J, Hülsemann J, Filser A. Moving Back to the Parental Home in Times of COVID-19: Consequences for Students’ Life Satisfaction. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(17):10659. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191710659

Chicago/Turabian StylePreetz, Richard, Julius Greifenberg, Julika Hülsemann, and Andreas Filser. 2022. "Moving Back to the Parental Home in Times of COVID-19: Consequences for Students’ Life Satisfaction" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 17: 10659. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191710659

APA StylePreetz, R., Greifenberg, J., Hülsemann, J., & Filser, A. (2022). Moving Back to the Parental Home in Times of COVID-19: Consequences for Students’ Life Satisfaction. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(17), 10659. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191710659