Evaluation of the Health Promoting Schools (CEPS) Program in the Balearic Islands, Spain

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

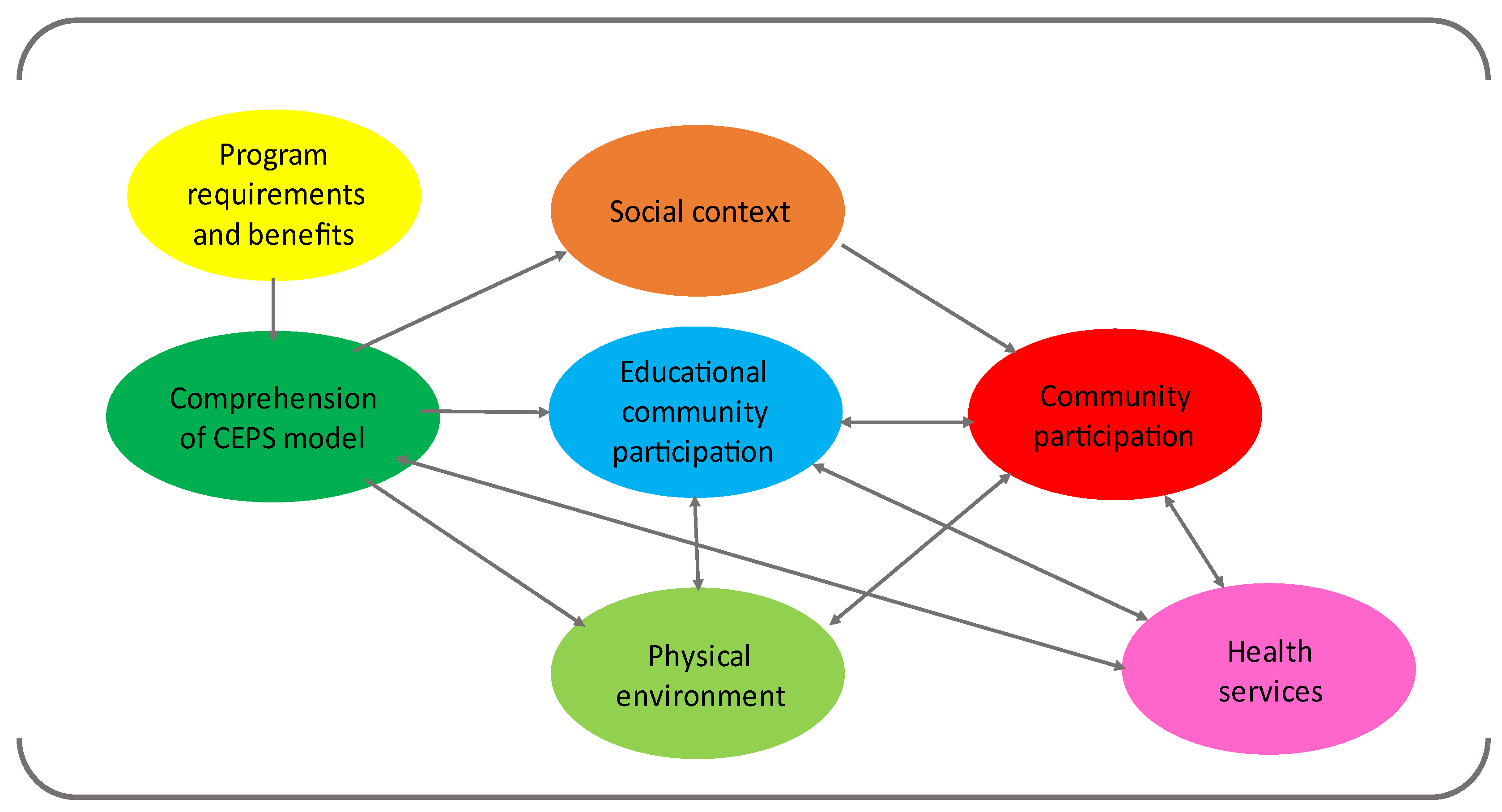

3.1. Structure Evaluation

3.2. Process Evaluation

3.2.1. Program Requirements and Benefits

We’ve talked about the problems that arise when making the health project, especially regarding the annual report. There are many documents to fulfill, and we don’t know how to do it. Just a simple evaluation report on the activities, the review, and improvement proposals would be enough.[School 7]

3.2.2. Comprehension of the CEPS Model

Due to the continuity of many activities, the health project has been established in the life of our educational community as a hallmark of the school.[School 5]

The school already had an environmental project, with a vegetable garden, as well as a social harmony committee with the participation of parents, students, and the management team. They have incorporated activities from the environmental project and the social harmony plan to the health project.[School 21]

In 2017–2018, we decided to join the health committee with the environmental committee.[School 31]

One of the objectives of the project is to improve social harmony, so the health committee has decided to work around equality and gender violence all the school year.[School 29]

We need to increase the distribution of fruits to ensure that students with economic difficulties can have them at least once per week. Many of them would not have access to sports facilities if it were not for the ones planned in the project.[School 10]

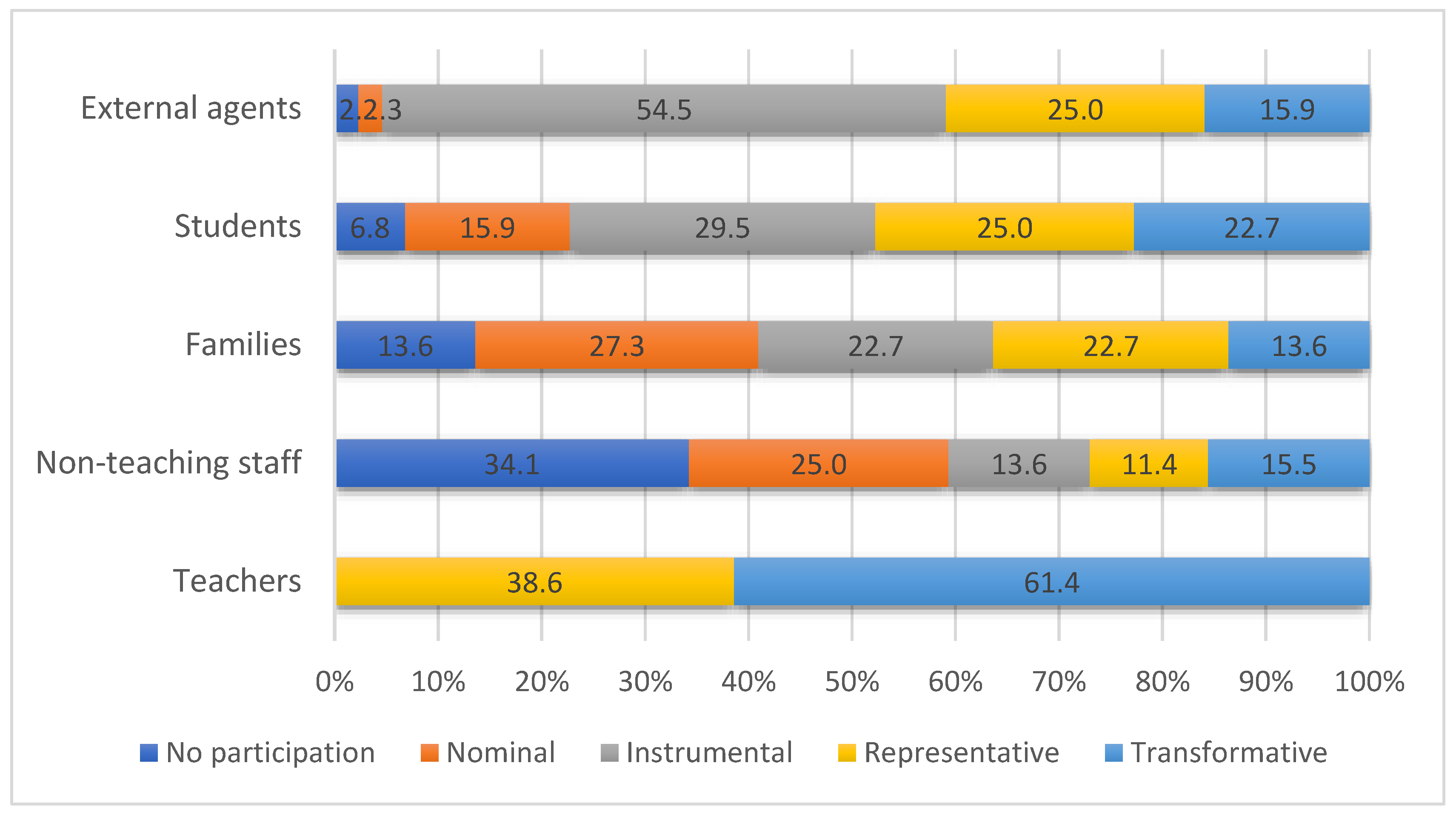

3.2.3. Educational Community Participation

Through the class delegate meetings, students have prepared food rules for the parties at the center.[School 24]

The health committee only wanted fruit juices for the parties. They asked for collaboration to the families, and they brought so many oranges that they didn’t fit in one room. It was a complete success.[School 22]

We included the person in charge of the kitchen in the health committee so we can have a more fluid relationship in this important part of our project: the school cafeteria.[School 9]

3.2.4. Community Participation

With the local Committee of Education, Health and Social services, all activities are offered to all schools of the Town Hall. It coordinates all planification and programming. The Town Hall supports the initiatives and searches for the required solutions. The parents’ associations are present, so the activities arrive to every family.[School 23]

3.2.5. Social Context

We decided to start with emotional awareness to improve the social harmony in this diverse environment… It is vital to give tools to our students to make them aware of their situation, their feelings, etc. As they only perceive their family situation, they could believe that only this reality exists.[School 22]

3.2.6. Physical Environment

We did a zumba activity, which was useful not only for promoting physical activity, but also for developing a sense of belonging to a community.[School 21]

The school police officer is highly active. Nobody smokes in the school entrance; he takes care of it. It works.[School 31]

3.2.7. Relationship with Health Services

3.3. Results Evaluation

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Variables | Categories | Low | Medium | High | TOTAL | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type of centre | Infant | 20 | 20 | 60 | 100 | 0.177 |

| Infant + Primary | 0 | 54.5 | 45.5 | 100 | ||

| Secondary | 4.8 | 52.4 | 42.9 | 100 | ||

| Adults | 0 | 100 | 0 | 100 | ||

| Infant + Primary + Secondary | 40 | 40 | 20 | 100 | ||

| Years in the CEPS Program | 2 | 0 | 67 | 33.3 | 100 | 0.673 |

| 3 | 8 | 46.2 | 46.2 | 100 | ||

| 4 | 50 | 0,0 | 50 | 100 | ||

| 5 | 8.3 | 58.3 | 33.3 | 100 | ||

| 6 | 7.1 | 50 | 42.9 | 100 | ||

| Situation analysis | No | 0 | 100 | 0 | 100 | 0.6 |

| Yes | 9.3 | 48.8 | 41.9 | 100 | ||

| CEPS training | No | 0 | 75 | 25 | 100 | 0.543 |

| Yes | 10 | 47.5 | 42.5 | 100 | ||

| CEPS grant | No | 21.1 | 52.6 | 26.3 | 100 | 0.029 |

| Yes | 0 | 48 | 52 | 100 | ||

| CEPS certificate | No | 14.3 | 50 | 35.7 | 100 | 0.689 |

| Yes | 6.7 | 50 | 43.3 | 100 | ||

| Commitment of to leave no one behind | No | 12.5 | 53.1 | 34.4 | 100 | 0.228 |

| Yes | 0 | 41.7 | 58.3 | 100 | ||

| Prioritisation of specific subpopulations | No | 10 | 46.7 | 43.3 | 100 | 0.806 |

| Yes | 7.1 | 57.1 | 35.7 | 100 | ||

| Advocacy actions favourable to health promotion | No | 9.5 | 47.6 | 42.9 | 100 | 0.955 |

| Yes | 8.7 | 52.2 | 39.1 | 100 | ||

| Coordination with other programs | No | 11.8 | 58.8 | 29.4 | 100 | 0.462 |

| Yes | 7.4 | 44.4 | 48.1 | 100 | ||

| Participation of teachers | Representative | 17.6 | 64.7 | 17.6 | 100 | 0.029 |

| Transformative | 3.7 | 40.7 | 55.6 | 100 | ||

| Participation of non-teaching staff | No participation | 6.7 | 60 | 33.3 | 100 | 0.422 |

| Nominal | 9.1 | 72.7 | 18.2 | 100 | ||

| Instrumental | 17 | 17 | 67 | 100 | ||

| Representative | 0 | 40 | 60 | 100 | ||

| Transformative | 14.3 | 28.6 | 57 | 100 | ||

| Participation of families | No participation | 16.7 | 83.3 | 0 | 100 | 0.684 |

| Nominal | 8.3 | 41.7 | 50 | 100 | ||

| Instrumental | 10 | 50 | 40 | 100 | ||

| Representative | 10 | 40 | 50 | 100 | ||

| Transformative | 0 | 50 | 50 | 100 | ||

| Participation of students | No participation | 0 | 66.7 | 33.3 | 100 | 0.447 |

| Nominal | 28.6 | 42.9 | 28.6 | 100 | ||

| Instrumental | 0 | 61.5 | 38.5 | 100 | ||

| Representative | 18.2 | 36.4 | 45.5 | 100 | ||

| Transformative | 0,0 | 50 | 50 | 100 | ||

| Participation of external agents | No participation | 100 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0.004 |

| Nominal | 100 | 0 | 0 | 100 | ||

| Instrumental | 4.2 | 45.8 | 50 | 100 | ||

| Representative | 9.1 | 63.6 | 27.3 | 100 | ||

| Transformative | 0 | 57.1 | 42.9 | 100 | ||

| Critical analysis of health problems | No | 16.7 | 54.2 | 29.2 | 100 | 0.071 |

| Yes | 0 | 45 | 55 | 100 | ||

| Relationship with health centre | No | 25 | 37.5 | 37.5 | 100 | 0.217 |

| Yes | 5.6 | 52.8 | 47.1 | 100 | ||

| Relationship with other health services | No | 9.4 | 53.1 | 37.5 | 100 | 0.751 |

| Yes | 8.3 | 41.7 | 50 | 100 | ||

| Consulta jove | No | 12 | 44 | 44 | 100 | 0.580 |

| Yes | 5.3 | 57.9 | 36.8 | 100 | ||

| Alerta escolar | No | 13.3 | 53.3 | 33.3 | 100 | 0.183 |

| Yes | 0 | 42.9 | 57.1 | 100 | ||

| Talks | No | 19 | 38.1 | 42.9 | 100 | 0.062 |

| Yes | 0 | 61 | 39 | 100 | ||

| Health results | No | 7.7 | 73 | 19,2 | 100 | 0.001 |

| Yes | 11.1 | 16.7 | 72.2 | 100 | ||

| Education results | No | 9.5 | 50 | 40.5 | 100 | 0.890 |

| Yes | 0 | 50 | 50 | 100 | ||

| Social harmony results | No | 9 | 56.3 | 34.4 | 100 | 0.341 |

| Yes | 8.3 | 33.3 | 58.3 | 100 | ||

| Democracy results | No | 9.3 | 51 | 39.5 | 100 | 0.478 |

| Yes | 0 | 50 | 50 | 100 |

References

- Centres Educatius Promotors de la Salut (CEPS). Available online: https://www.caib.es/sites/ceps/ca/portada_ceps/?campa=yes (accessed on 17 August 2021).

- World Health Organization. Making Every School a Health Promoting School. Implementation Guidance. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240025073 (accessed on 19 August 2022).

- Schools for Health in Europe. Whole School Approach. Available online: https://www.schoolsforhealth.org/concepts/whole-school-approach (accessed on 11 January 2021).

- The Otawa Charter for Health Promotion. Available online: https://www.who.int/teams/health-promotion/enhanced-wellbeing/first-global-conference (accessed on 16 August 2022).

- Pommier, J.; Guével, M.R.; Jourdan, D. Evaluation of health promotion in schools: A realistic evaluation approach using mixed methods. BMC Public Health 2010, 28, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Researching Health promotion in Schools (Marjorita Sormunen). Available online: https://www.schoolsforhealth.org/sites/default/files/editor/academy/sormunen-she-academy-2017.pdf (accessed on 16 August 2022).

- Portell, M.; Anguera, M.T.; Chacón-Moscoso, S.; Sanduvete-Chaves, S. Guidelines for reporting evaluations based on observational methodology. Psicothema 2015, 27, 283–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan American Health Organization. El enfoque Innov8 para examinar los programas nacionales de salud para que nadie se quede atrás. Manual técnico. 2017. Available online: https://iris.paho.org/handle/10665.2/34933 (accessed on 16 August 2022).

- The European Network of Health Promoting Schools. The Alliance of Education and Health. Available online: https://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0004/252391/E62361.pdf?ua=1 (accessed on 17 August 2022).

- Criterios de calidad de la Red Aragonesa de Proyectos de Promoción de Salud. Gobierno de Aragón. Departamento de Salud y Consumo. Available online: https://www.aragon.es/documents/20127/674325/CRITERIOS_RAPPS.PDF/b125db7b-2bca-1e39-a582-c7e5665f03ef (accessed on 16 August 2022).

- Alimentació saludable i vida activa. Govern de les Illes Balears. Entorn escolar. Available online: http://e-alvac.caib.es/es/entorno-escolar.html (accessed on 16 August 2022).

- Pla d’addiccions i drogodependències de les Illes Balears (PADIB). Available online: https://www.caib.es/sites/padib/ca/portada-9943/ (accessed on 16 August 2022).

- Amb tots els sentits. Programa de educación afectivo sexual en el ámbito educativo. Available online: https://www.caib.es/sites/salutsexual/es/amb_tots_els_sentits/ (accessed on 16 August 2022).

- White, S.C. Depoliticising development: The uses and abuses of participation. In Development, NGOs and Civil Society; Oxfam: London, UK, 2000; Available online: https://oxfamilibrary.openrepository.com/bitstream/handle/10546/121451/bk-development-ngos-civil-society-010100-en.pdf?sequence=8#page=143 (accessed on 16 August 2022).

- HEPS Inventory Tool. An Inventory Tool including Quality Assessment of School Interventions on Healthy Eating and Physical Activity. 2010. Available online: https://www.schoolsforhealth.org/sites/default/files/editor/Teachers%20resources/heps-inventory-tool-english.pdf (accessed on 16 August 2022).

- Dadaczynski, K.; Hering, T. Health Promoting Schools in Germany. Mapping the Implementation of Holistic Strategies to Tackle NCDs and Promote Health. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meiklejohn, S.; Peeters, A.; Palermo, C. Championing Health Promoting Schools: A secondary school case study from Victoria, Australia. Health Educ. J. 2020, 80, 187–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Public Health England. Social Marketing Strategy 2017–2020. 2017. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/646715/public_health_england_marketing_strategy_2017_to_2020.pdf (accessed on 16 August 2022).

- Bentsen, P.; Bonde, A.H.; Schneller, M.B.; Danielsen, D.; Bruselius-Jensen, M.; Aagaard-Hansen, J. Danish ‘add-in’ school-based health promotion: Integrating health in curriculum time. Health Promot. Int. 2020, 35, e70–e77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hahnraths, M.T.H.; Willeboordse, M.; Jungbauer, A.; de Gier, C.; Schouten, C.; van Schayck, C.P. “Mummy, Can I Join a Sports Club?” A Qualitative Study on the Impact of Health-Promoting Schools on Health Behaviours in the Home Setting. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serda, B.C.; Planas-Llado, A.; delValle, A.; Soler-Maso, P. Health promotion in secondary schools: Participatory process for constructing a self-assessment tool. Health Promot. Int. 2022, 37, daab123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Estudio HBSC. Available online: https://www.hbsc.es/ (accessed on 16 August 2022).

- School Health Promotion: Evidence for Effective Action. Background Paper SHE Factsheet 2. Available online: https://www.schoolsforhealth.org/sites/default/files/editor/fact-sheets/she-factsheet2-background-paper-school-health-promotion-evidence.pdf (accessed on 16 August 2022).

- Sustainable Development Goals. Available online: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/ (accessed on 16 August 2022).

- Langford, R.; Bonell, C.P.; Jones, H.E.; Pouliou, T.; Murphy, S.M.; Waters, E.; Komro, K.A.; Gibbs, L.F.; Magnus, D.; Campbell, R. The WHO Health Promoting School framework for improving the health and well-being of students and their academic achievement. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2014, 16, CD008958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnes, M.D.; Hanson, C.L.; Novilla, L.B.; Magnusson, B.M.; Crandall, A.C.; Bradford, G. Family-centered Health promotion: Perspectives for engaging families and achieving better health outcomes. Inquiry 2020, 57, 46958020923537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lista de chequeo para el análisis de la equidad en estrategias, programas y actividades (EPAs) de salud. Gobierno de España. Ministerio de Sanidad. Available online: https://www.sanidad.gob.es/profesionales/saludPublica/prevPromocion/promocion/desigualdadSalud/docs/2022_listadechequeo_equidadVF.pdf (accessed on 18 August 2022).

- Health Literacy in Schools. State of the Art. SHE Factsheet 6. Available online: https://www.schoolsforhealth.org/sites/default/files/editor/fact-sheets/factsheet-2020-english.pdf (accessed on 16 August 2022).

- Casañas, R.; Más-Expósito, L.; Teixidó, M.; Lalucat-Jo, L. Programas de alfabetización para la promoción de la salud mental en el ámbito escolar. Informe SESPAS 2020. Gac. Sanit. 2020, 34, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Dongen, B.M.; de Vries, I.M.; Ridder, M.A.M.; Renders, C.M.; Steenhuis, I.H.M. Opportunities for Capacity Building to Create Healthy School Communities in the Netherlands: Focus Group Discussions with Dutch Pupils. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 630513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sprague, L.; Pufall, E.; Connolly, N. From Consultation to Shared Decision-Making: Youth Engagement Strategies for Promoting School and Community Wellbeing. J. Sch. Health 2020, 90, 976–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnston, R.; Norman, J.; Furber, S.; Parkinson, J. The barriers and enablers to implementing the New South Wales Healthy School Canteen Strategy in secondary schools in the Illawarra and Shoalhaven regions –A qualitative study. Health Promot. J. Austral. 2022, 33, 686–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | Categories | Only Structure | Structure, Process & Outcomes | TOTAL |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type of school | Infant * | 2 (5.0) | 5 (11.4) | 7 (8.3) |

| Infant + Primary | 1 (2.5) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.2) | |

| Secondary | 9 (22.5) | 11 (25.0) | 20 (23.8) | |

| Adults | 16 (40.0) | 21 (47.7) | 37 (44.0) | |

| Infant + Primary + Secondary * | 10 (25.0) | 5 (11.4) | 15 (17.9) | |

| Total | 40 (100.0) | 44 (100.0) | 84 (100.0) | |

| Years participating in the CEPS Program | 1 | 31 (75.0) | 0 (0.0) | 31 (36.9) |

| 2 | 9 (22.5) | 3 (6.8) | 12 (14.3) | |

| 3 | 0 (0.0) | 13 (29.5) | 13 (15.5) | |

| 4 | 0 (0.0) | 2 (4.5) | 2 (2.4) | |

| 5 | 0 (0.0) | 12 (27.3) | 12 (14.3) | |

| 6 | 0 (0.0) | 14 (31.8) | 14 (16.7) | |

| Total | 40 (100.0) | 44 (100.0) | 84 (100.0) | |

| Number of situation analysis performed | 0 | 8 (21.6) | 1 (2.6) | 9 (10.7) |

| 1 | 21 (56.8) | 9 (23.7) | 30 (35.7) | |

| 2 | 7 (18.9) | 18 (47.4) | 25 (29.8) | |

| 3 | 1 (2.7) | 7 (18.4) | 8 (9.5) | |

| 4 | 0 (100.0) | 3 (7.9) | 3 (3.6) | |

| Total | 40 (100.0) | 44 (100.0) | 84 (100.0) | |

| Participation of any teacher in CEPS training | 0 | 18 (45.0) | 4 (9.1) | 22 (26.2) |

| 1 | 18 (45.0) | 14 (31.8) | 32 (38.19 | |

| 2 | 4 (10.0) | 13 (29.5) | 17 (20.2) | |

| 3 | 0 (0.0) | 8 (18.2) | 8 (9.5) | |

| 4 | 0 (0.0) | 5 (11.4) | 5 (6.0) | |

| Total | 40 (100.0) | 44 (100.0) | 84 (100.0) | |

| CEPS grant | 0 | 33 (82.5) | 19 (43.2) | 52 (61.9) |

| 1 | 4 (10.0) | 12 (27.3) | 16 (19.0) | |

| 2 | 3 (7.5) | 6 (13.6) | 9 (10.7) | |

| 3 | 0 (0.0) | 7 (15.9) | 7 (8.3) | |

| Total | 40 (100.0) | 44 (100.0) | 84 (100.0) | |

| CEPS certificate | Yes | 0 (0.0) | 30 (68.2) | 30 (35.7) |

| No | 40 (100.0) | 14 (31.8) | 54 (64.3) | |

| Total | 40 (100.0) | 44 (100.0) | 84 (100.0) |

| Process | Number | % |

|---|---|---|

| Commitment to leave no one behind | 12 | 27.3 |

| Prioritization of any special population | 14 | 31.8 |

| Coordination with other programs | 27 | 61.4 |

| Advocacy actions favorable to health promotion | 23 | 52.3 |

| Use of PHD programs & questionnaires | Number | % |

| - Bon dia salut (abilities for life) | 2 | 4.5 |

| - Decideix (prevention of addictions) | 6 | 13.6 |

| - THC supera el repte (prevention of cannabis consumption) | 2 | 4.5 |

| - Respiraire (prevention of tobacco consumption) | 5 | 11.4 |

| - Amb tots els sentits (sexual & affective education) | 3 | 6.8 |

| - Sexe segur i responsable (prevention of sexually transmitted diseases) | 5 | 11.4 |

| - Other programs (prevention of addictions; sexual education) | 9 | 20.5 |

| - Questionaris dieta mediterrània/vida activa (healthy food/physical activity) | 6 | 14 |

| - Other questionnaires (healthy food & physical activity; general health) | 20 | 45.5 |

| Process | Number | % |

| Critical analysis of health problems | 20 | 45.5 |

| Relationship with health center | 36 | 81.8 |

| Relationship with other health services | 12 | 27.3 |

| Activities performed by health professionals: | 20 | 45.5 |

| - Health professional in the health committee | 12 | 27.3 |

| - Informal seminars | 23 | 52.3 |

| - Alerta escolar (training of teachers in health emergencies) | 14 | 31.8 |

| - Consulta jove (health consultancy at school) | 19 | 43.2 |

| - Other activities | 14 | 31.8 |

| Results | Number | % |

| Health | 18 | 40.9 |

| Education | 2 | 4.5 |

| Social harmony | 12 | 27.3 |

| Democracy | 1 | 2.3 |

| Total schools | 44 | 100 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ramos, M.; Tejera, E.; Cabeza, E. Evaluation of the Health Promoting Schools (CEPS) Program in the Balearic Islands, Spain. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10756. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191710756

Ramos M, Tejera E, Cabeza E. Evaluation of the Health Promoting Schools (CEPS) Program in the Balearic Islands, Spain. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(17):10756. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191710756

Chicago/Turabian StyleRamos, Maria, Elena Tejera, and Elena Cabeza. 2022. "Evaluation of the Health Promoting Schools (CEPS) Program in the Balearic Islands, Spain" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 17: 10756. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191710756

APA StyleRamos, M., Tejera, E., & Cabeza, E. (2022). Evaluation of the Health Promoting Schools (CEPS) Program in the Balearic Islands, Spain. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(17), 10756. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191710756