Factor Analysis Affecting Degree of Depression in Family Caregivers of Patients with Spinal Cord Injury: A Cross-Sectional Pilot Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Population

2.2. Dependent Variables

Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale

2.3. Independent Variables

2.3.1. Demographic Characteristics

2.3.2. General Characteristics of Family Caregivers Related to Care

2.3.3. Life Satisfaction of Families with Spinal Cord Disabilities

2.4. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. General Characteristics (Caregivers and Patients)

3.2. Depression, Physical Health, Household Income, Leisure and Social Activity, Family Relations, and Overall Life Satisfaction in Caregivers

3.3. Comparison of Caregiver’s Depression, Physical Health, Household Income, Leisure and Social Activity, Family Relations, Overall Life Satisfaction and General Characteristics (Caregivers and Patients)

3.4. Correlation of Physical Health, Household Income, Leisure and Social Activity, Family Relations, and Overall Life Satisfaction in General Status in Caregiver

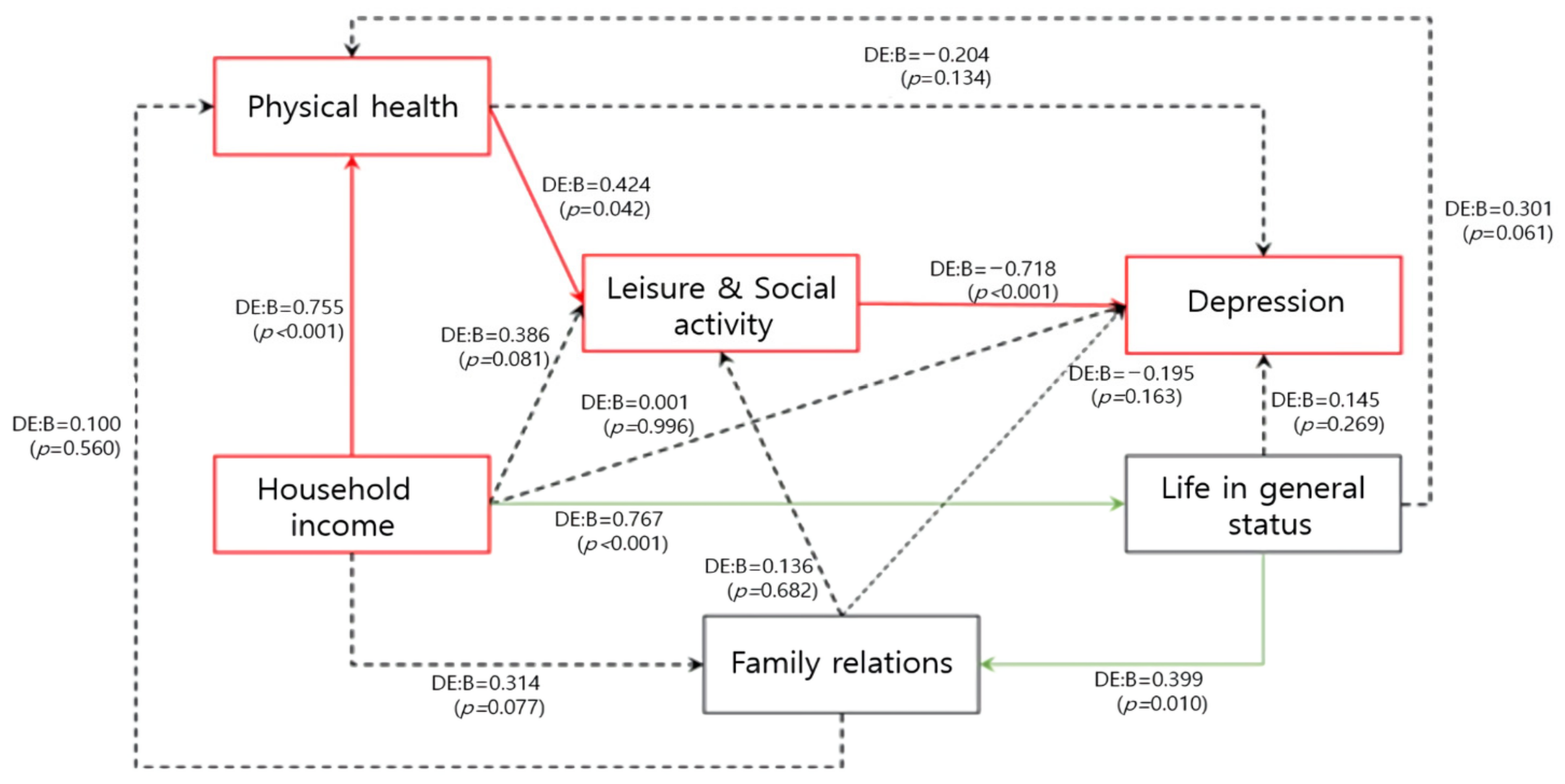

3.5. Factor Association of Depression in Caregivers

3.6. Pathway Factors of Caregiver Depression

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Molazem, Z.; Falahati, T.; Jahanbin, I.; Ghadakpour, S.; Jafari, P. The effect of psycho educational interventions on general health of family caregivers of patients with spinal cord injury: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Jundishapur J. Chronic Dis. Care 2013, 2, 31–39. [Google Scholar]

- Nas, K.; Yazmalar, L.; Şah, V.; Aydın, A.; Öneş, K. Rehabilitation of spinal cord injuries. World J. Orthop. 2015, 6, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pili, R.; Gaviano, L.; Pili, L.; Petretto, D.R. Ageing, disability, and spinal cord injury: Some issues of analysis. Curr. Gerontol. Geriatr. Res. 2018, 2018, 4017858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, A.G.; Karabukayeva, A.; Rainey, C.; Kelly, R.J.; Patterson, J.; Wade, J.; Feldman, S.S. Perspectives on life following a traumatic spinal cord injury. Disabil. Health J. 2021, 14, 101067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weitzenkamp, D.A.; Gerhart, K.A.; Charlifue, S.W.; Whiteneck, G.G.; Savic, G. Spouses of spinal cord injury survivors: The added impact of caregiving. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 1997, 78, 822–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeSanto-Madeya, S. Adaptation to spinal cord injury for families post-injury. Nurs. Sci. Q. 2009, 22, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, H.J.; Lee, S.Y. Family Support Plan for Severe and Moderately Disabled—Focused on Families with Spinal Cord Disability; Report No.: Politic Report 19-07; Korea Disabled People’s Development Institute: Seoul, Korea, 2019; p. 139. [Google Scholar]

- Song, J.M. Burden and Quality of Life for Family Members of Spinal Cord Injury Patients. Ph.D. Thesis, Hanyang University, Graduate School, Seoul, Korea, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs, W.B.; Walsh, G.S.; Miller, F.D. Neuronal survival and p73/p63/p53: A family affair. Neuroscientist 2004, 10, 443–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, M.S. A Study on Stress and Adaptation of Families with Spinal Cord Disorders: Focusing on the Interactive Buffering Effect of Factors of Flexibility for Family Adaptation. Master Thesis, Graduate School of Seoul National University, Seoul, Korea, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y.-R.; Kim, Y.; Kim, M. A Convergent study of the physical related quality of life using SF-8 of stroke patient’s caregiver. J. Korea Converg. Soc. 2017, 8, 119–127. [Google Scholar]

- Park, J.H.; Kim, K.W. A review of the epidemiology of depression in Korea. J. Korean Med. Assoc. 2011, 54, 362–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, S.-J.; Park, E.-Y. Relationship between caregiving burden and depression in caregivers of individuals with intellectual disabilities in Korea. J. Ment. Health 2017, 26, 50–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fong, T.K.-H.; Cheung, T.; Chan, W.-C.; Cheng, C.P.-W. Depression, Anxiety and Stress on Caregivers of Persons with Dementia (CGPWD) in Hong Kong amid COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radloff, L.S. The CES-D Scale: A Self-Report Depression Scale for Research in the General Population. Appl. Psychol. Meas. 1977, 1, 385–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chon, K.K.; Rhee, M.K. Preliminary Development of Korean Version of CES-D. Korean J. Clin. Psychol. 1992, 11, 65–79. [Google Scholar]

- Wyndaele, M.; Wyndaele, J.-J. Incidence, prevalence and epidemiology of spinal cord injury: What learns a worldwide literature survey? Spinal Cord 2006, 44, 523–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, Y.H.; Kim, Y.S.; Han, S.K. A Study on Factors Influencing the Independent Living of People with Spinal Cord Injury. J. Rehabil. Res. 2013, 17, 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Post, M.; Bloemen, J.; De Witte, L. Burden of support for partners of persons with spinal cord injuries. Spinal Cord 2005, 43, 311–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeyathevan, G.; Cameron, J.I.; Craven, B.C.; Munce, S.E.; Jaglal, S.B. Re-building relationships after a spinal cord injury: Experiences of family caregivers and care recipients. BMC Neurol. 2019, 19, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charlifue, S.; Botticello, A.; Kolakowsky-Hayner, S.; Richards, J.; Tulsky, D. Family caregivers of individuals with spinal cord injury: Exploring the stresses and benefits. Spinal Cord 2016, 54, 732–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryerson Espino, S.L.; O’Rourke, K.; Kelly, E.H.; January, A.M.; Vogel, L.C. Coping, Social Support, and Caregiver Well-Being With Families Living With SCI: A Mixed Methods Study. Top Spinal Cord Inj. Rehabil. 2022, 28, 78–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khazaeipour, Z.; Ahmadipour, E.; Rahimi-Movaghar, V.; Ahmadipour, F.; Vaccaro, A.; Babakhani, B. Association of pain, social support and socioeconomic indicators in patients with spinal cord injury in Iran. Spinal Cord 2017, 55, 180–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conti, A.; Clari, M.; Nolan, M.; Wallace, E.; Tommasini, M.; Mozzone, S.; Campagna, S. The relationship between psychological and physical secondary conditions and family caregiver burden in spinal cord injury: A correlational study. Top Spinal Cord Inj. Rehabil. 2019, 25, 271–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zanini, C.; Amann, J.; Brach, M.; Gemperli, A.; Rubinelli, S. The challenges characterizing the lived experience of caregiving. A qualitative study in the field of spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 2021, 59, 493–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, J.; Barzallo, D.P.; Rubinelli, S.; Münzel, N.; Brach, M.; Gemperli, A. Professional home care and the objective care burden for family caregivers of persons with spinal cord injury: Cross sectional survey. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. Adv. 2021, 3, 100014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seçinti, E.; Yavuz, H.M.; Selçuk, B. Feelings of burden among family caregivers of people with spinal cord injury in Turkey. Spinal Cord 2017, 55, 782–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, E.-M.; Lee, S.-A.; Gu, J.-W. The Factors Related to Musculoskeletal Symptoms of Family Care-Givers who Have a Patient with Brain Damage. J. Korea Acad. Ind. Coop. Soc. 2017, 18, 336–344. [Google Scholar]

- Darragh, A.R.; Sommerich, C.M.; Lavender, S.A.; Tanner, K.J.; Vogel, K.; Campo, M. Musculoskeletal discomfort, physical demand, and caregiving activities in informal caregivers. J. Appl. Gerontol. 2015, 34, 734–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuzu, D.; Perrin, P.B.; Pugh, M., Jr. Spinal Cord Injury/Disorder Function, Affiliate Stigma, and Caregiver Burden in Turkey. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2021, 13, 1376–1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimzadeh, M.H.; Shojaei, B.-S.; Golhasani-Keshtan, F.; Soltani-Moghaddas, S.H.; Fattahi, A.S.; Mazloumi, S.M. Quality of life and the related factors in spouses of veterans with chronic spinal cord injury. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2013, 11, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Variables | Caregiver | Patient | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | n | % | |

| Age | ||||

| ≥60 | 11 | 36.7 | 12 | 40.0 |

| <60 | 19 | 63.3 | 18 | 60.0 |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 6 | 20.0 | 25 | 83.3 |

| Female | 24 | 80.0 | 5 | 16.7 |

| Education level | ||||

| ≥College | 10 | 33.3 | 12 | 40.0 |

| High school | 10 | 33.3 | 13 | 43.3 |

| ≤Middle school | 10 | 33.3 | 5 | 16.7 |

| Economic activity | ||||

| Yes | 13 | 43.3 | 11 | 36.7 |

| No | 17 | 56.7 | 19 | 63.3 |

| Married status | ||||

| Married | 25 | 83.3 | 23 | 23.3 |

| Single | 0 | 0.0 | 7 | 76.7 |

| Other (separated, widowed) | 5 | 16.7 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Religion | ||||

| Yes | 18 | 60.0 | 13 | 43.3 |

| No | 12 | 40.0 | 17 | 56.7 |

| Relationship with the patient | ||||

| Spouse | 19 | 63.3 | - | - |

| Parents | 3 | 10.0 | - | - |

| Children | 4 | 13.3 | - | - |

| Other (grandparents, grandchildren, brothers, and sisters) | 4 | 13.3 | - | - |

| Patient care shifting | ||||

| Yes | 7 | 23.3 | - | - |

| No | 23 | 76.7 | - | - |

| Total | 30 | 100.0 | 30 | 100.0 |

| Variables | Min–Max | M [SD] | Skewness + | Kurtosis ++ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depression | 1–5 | 2.56 [0.82] | 0.361 | 0.333 |

| Physical health | 1–4 | 2.70 [0.79] | −0.716 | 0.414 |

| Household income | 1–4 | 2.70 [0.75] | −1.010 | 0.977 |

| Leisure and Social activity | 1–4 | 2.50 [0.86] | −0.174 | −0.491 |

| Family relations | 1–4 | 2.90 [0.76] | −0.842 | 1.269 |

| Life-in-general status | 1–4 | 2.50 [0.86] | −0.174 | −0.491 |

| Variables | Depression | Physical Health | Household Income | Leisure and Social Activity | Family Relations | Life-in-General Status | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M [SD] | Z + or H ++ [p] | M [SD] | Z + or H ++ [p] | M [SD] | Z + or H ++ [p] | M [SD] | Z + or H ++ [p] | M [SD] | Z + or H ++ [p] | M [SD] | Z + or H ++ [p] | |

| Caregiver | ||||||||||||

| Age | ||||||||||||

| ≥60 | 2.58 [0.73] | −0.043 [0.966] | 2.45 [0.69] | −1.540 [0.124] | 2.73 [0.79] | −0.129 [0.898] | 2.45 [0.93] | −0.138 [890] | 2.91 [0.94] | −0.200 [0.841] | 2.27 [0.91] | −1.193 [0.233] |

| <60 | 2.55 [0.89] | 2.84 [0.83] | 2.68 [0.75] | 2.53 [0.84] | 2.89 [0.66] | 2.63 [0.83] | ||||||

| Sex | ||||||||||||

| Male | 3.33 [0.81] | −1.739 [0.082] | 3.17 [0.81] | −2.209 [0.027] | 3.00 [0.63] | −1.024 [0.306] | 2.83 [0.75] | −0.995 [0.320] | 3.17 [0.75] | −0.935 [0.350] | 2.67 [0.82] | −0.359 [0.719] |

| Female | 2.84 [0.72] | 2.55 [0.72] | 2.63 [0.77] | 2.42 [0.88] | 2.83 [0.76] | 2.46 [0.88] | ||||||

| Education level | ||||||||||||

| ≥College | 2.40 [0.78] | 1.823 [0.402] | 3.00 [0.67] | 4.818 [0.090] | 2.90 [0.57] | 1.334 [0.513] | 2.70 [0.82] | 0.626 [0.731] | 3.10 [0.57] | 3.206 [0.201] | 2.70 [0.82] | 2.581 [0.275] |

| High school | 2.36 [0.66] | 2.90 [0.57] | 2.80 [0.42] | 2.50 [0.71] | 3.10 [0.57] | 2.70 [0.48] | ||||||

| ≤Middle school | 2.93 [0.96] | 2.20 [0.92] | 2.40 [1.08] | 2.30 [1.06] | 2.50 [0.97] | 2.10 [1.10] | ||||||

| Economic activity | ||||||||||||

| Yes | 2.26 [0.65] | −1.299 [0.194] | 3.08 [0.49] | −2.282 [0.022] | 3.00 [0.58] | −1.803 [0.071] | 2.69 [0.75] | −0.826 [0.409] | 3.15 [0.38] | −1.484 [0.138] | 2.85 [0.69] | −1.852 [0.064] |

| No | 2.79 [0.89] | 2.41 [0.87] | 2.47 [0.80] | 2.35 [0.93] | 2.71 [0.92] | 2.24 [0.90] | ||||||

| Married status | ||||||||||||

| Married | 2.60 [0.89] | −0.752 [0.452] | 2.64 [0.86] | −0.948 [0.343] | 2.68 [0.80] | −0.166 [0.868] | 2.44 [0.92] | −0.950 [0.342] | 2.88 [0.03] | −0.162 [0.871] | 2.44 [0.92] | −1.327 [0.342] |

| Single | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||||||

| Other (separated, widowed) | 2.35 [0.30] | 3.00 [0.00] | 2.80 [0.45] | 2.80 [0.45] | 3.00 [0.01] | 2.80 [0.45] | ||||||

| Religion | ||||||||||||

| Yes | 2.59 [0.79] | −0.996 [0.319] | 2.89 [0.76] | −1.587 [0.113] | 2.83 [0.71] | −1.114 [0.265] | 2.50 [0.86] | −0.113 [0.910] | 3.00 [0.77] | −0.960 [0.337] | 2.56 [0.86] | −0.406 [0.684] |

| No | 2.52 [0.91] | 2.42 [0.79] | 2.50 [0.80] | 2.50 [0.91] | 2.75 [0.75] | 2.42 [0.90] | ||||||

| Relationship with the patient | ||||||||||||

| Spouse | 2.64 [0.98] | 1.080 [0.782] | 2.53 [0.84] | 6.983 [0.072] | 2.58 [0.90] | 1.573 [0.665] | 2.53 [1.02] | 2.049 [0.562] | 2.53 [1.02] | 1.167 [0.761] | 2.47 [1.02] | 3.371 [0.338] |

| Parents | 2.62 [0.45] | 3.67 [0.58] | 3.00 [0.01] | 2.00 [0.01] | 2.00 [0.01] | 2.00 [0.01] | ||||||

| Children | 2.51 [0.66] | 2.50 [0.58] | 3.00 [0.01] | 2.50 [0.29] | 2.50 [0.58] | 2.50 [0.58] | ||||||

| Other (grandparents, grandchildren, brother, and sister) | 2.20 [0.18] | 3.00 [0.01] | 2.75 [0.50] | 2.75 [0.50] | 2.75 [0.50] | 3.00 [0.01] | ||||||

| Patient care shifting | ||||||||||||

| Yes | 2.55 [0.71] | −0.025 [0.980] | 2.57 [0.54] | −0.836 [0.403] | 2.86 [0.38] | −0.499 [0.618] | 2.29 [0.76] | −0.758 [0.448] | 3.29 [0.49] | −1.568 [0.117] | 2.43 [0.54] | −0.392 [0.695] |

| No | 2.56 [0.87] | 2.74 [0.86] | 2.65 [0.83] | 2.57 [0.90] | 2.78 [0.80] | 2.52 [0.95] | ||||||

| Patients | ||||||||||||

| Age | ||||||||||||

| ≥60 | 2.70 [0.66] | −0.700 [0.484] | 2.75 [0.87] | −0.216 [0.829] | 2.83 [0.72] | −0.912 [0.362] | 2.42 [0.90] | −0.406 [0.684] | 2.83 [0.84] | −0.369 [0.712] | 2.42 [0.79] | −0.609 [0.542] |

| <60 | 2.47 [0.93] | 2.67 [0.77] | 2.61 [0.78] | 2.56 [0.86] | 2.94 [0.73] | 2.56 [0.92] | ||||||

| Sex | ||||||||||||

| Male | 2.62 [0.84] | −0.752 [−0.452] | 2.64 [0.81] | −0.853 [0.393] | 2.64 [0.76] | −0.899 [0.369] | 2.40 [0.87] | −1.424 [0.154] | 2.84 [0.80] | −0.938 [0.318] | 2.40 [0.87] | −1.424 [0.154] |

| Female | 2.24 [0.77] | 3.00 [0.71] | 3.00 [0.71] | 3.00 [0.71] | 3.20 [0.45] | 3.00 [0.71] | ||||||

| Education level | ||||||||||||

| ≥College | 2.10 [0.67] | 5.381 [0.068] | 2.92 [0.52] | 1.980 [0.371] | 2.83 [0.58] | 1.666 [0.430] | 2.83 [0.72] | 4.699 [0.095] | 3.08 [0.67] | 2.479 [0.289] | 2.83 [0.72] | 6.179 [0.046] |

| High school | 2.78 [0.78] | 2.69 [0.75] | 2.77 [0.60] | 2.46 [0.88] | 2.92 [0.76] | 2.54 [0.78] | ||||||

| ≤Middle school | 3.10 [0.85] | 2.20 [1.30] | 2.20 [1.30] | 1.80 [0.84] | 2.40 [0.89] | 1.60 [0.89] | ||||||

| Economic activity | ||||||||||||

| Yes | 2.04 [0.71] | −2.478 [0.013] | 2.91 [0.54] | −0.953 [0.340] | 2.91 [0.54] | −0.978 [0.328] | 2.82 [0.75] | −1.400 [0.162] | 3.09 [0.70] | −0.926 [0.355] | 2.73 [0.79] | −0.872 [0.383] |

| No | 2.86 [0.74] | 2.58 [0.90] | 2.58 [0.84] | 2.32 [0.89] | 2.79 [0.79] | 2.37 [0.90] | ||||||

| Married status | ||||||||||||

| Married | 2.60 [0.89] | −0.752 [0.452] | 2.70 [0.88] | −0.948 [0.343] | 2.68 [0.80] | −0.166 [0.868] | 2.44 [0.95] | −0.950 [0.342] | 2.88 [0.83] | −0.162 [0.871] | 2.44 [0.92] | −0.950 [0.342] |

| Single | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||||||

| Other (separated, widowed) | 2.35 [0.30] | 3.00 [0.00] | 2.80 [0.45] | 2.80 [0.45] | 3.00 [0.00] | 2.80 [0.45] | ||||||

| Religion | ||||||||||||

| Yes | 2.59 [0.79] | −0.042 [0.967] | 2.89 [0.76] | −1.141 [0.254] | 2.83 [0.71] | −1.252 [0.211] | 2.50 [0.86] | −1.339 [0.181] | 3.00 [0.77] | −0.949 [0.343] | 2.56 [0.86] | −1.540 0[.124] |

| No | 2.52 [0.91] | 2.42 [0.79] | 2.50 [0.80] | 2.50 [0.91] | 2.75 [0.75] | 2.42 [0.90] | ||||||

| Total | 2.56 [0.82] | 2.70 [0.79] | 2.70 [0.75] | 2.50 [0.86] | 2.90 [0.76] | 2.50 [0.86] | ||||||

| Variables | Physical Health | Household Income | Leisure and Social Activity | Family Relations | Life in General Status | Depression |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| r [p] | r [p] | r [p] | r [p] | r [p] | r [p] | |

| Physical health | 1 | |||||

| Household income | 0.582 [0.001] | 1 | ||||

| Leisure and Social activity | 0.559 [0.001] | 0.534 [0.002] | 1 | |||

| Family relations | 0.488 [0.006] | 0.528 [0.003] | 0.433 [0.017] | 1 | ||

| Life-in-general status | 0.634 [<0.001] | 0.583 [0.001] | 0.841 [<0.001] | 0.597 [0.001] | 1 | |

| Depression | −0.555 [0.001] | −0.429 [0.018] | −0.770 [<0.001] | −0.466 [0.009] | −646 [<0.001] | 1 |

| Variables | Model 1 | Model 2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B [β] | t [p] | B [β] | t [p] | |

| [Constants] | 5.107 [-] | 13.567 [<0.001] | 3.995 [-] | 6.318 [<0.001] |

| Physical health | −0.204 [−0.196] | −1.218 [0.235] | −0.196 [−0.189] | −1.285 [0.212] |

| Household income | 0.001 [0.001] | 0.006 [0.996] | 0.018 [0.016] | 0.111 [0.913] |

| Leisure and Social activity | −0.718 [0.200] | −3.584 [0.001] | −0.606 [−0.633] | −3.229 [0.004] |

| Family relations | −0.195 [0.161] | −1.209 [0.238] | −0.149 [−0.137] | −0.997 [0.329] |

| Life-in-general status | 0.145 [0.231] | 0.627 [0.537] | 0.056 [0.059] | 0.263 [0.795] |

| Patients Economic activity -No [ref: Yes] | 0.438 [0.260] | 2.607 [0.016] | ||

| R2, Adj R2 | 0.746, 0.693 | 0.806, 0.744 | ||

| F, p | 14.068, <0.001 | 13.042, <0.001 | ||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, S.-J.; Kim, M.-G.; Kim, J.h.; Min, Y.-S.; Kim, C.-H.; Kim, K.-T.; Hwang, J.-M. Factor Analysis Affecting Degree of Depression in Family Caregivers of Patients with Spinal Cord Injury: A Cross-Sectional Pilot Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10878. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191710878

Lee S-J, Kim M-G, Kim Jh, Min Y-S, Kim C-H, Kim K-T, Hwang J-M. Factor Analysis Affecting Degree of Depression in Family Caregivers of Patients with Spinal Cord Injury: A Cross-Sectional Pilot Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(17):10878. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191710878

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Su-Jin, Myung-Gwan Kim, Jung hee Kim, Yu-Sun Min, Chul-Hyun Kim, Kyoung-Tae Kim, and Jong-Moon Hwang. 2022. "Factor Analysis Affecting Degree of Depression in Family Caregivers of Patients with Spinal Cord Injury: A Cross-Sectional Pilot Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 17: 10878. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191710878

APA StyleLee, S.-J., Kim, M.-G., Kim, J. h., Min, Y.-S., Kim, C.-H., Kim, K.-T., & Hwang, J.-M. (2022). Factor Analysis Affecting Degree of Depression in Family Caregivers of Patients with Spinal Cord Injury: A Cross-Sectional Pilot Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(17), 10878. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191710878