The Role of Personality and Top Management Support in Continuance Intention to Use Electronic Health Record Systems among Nurses

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Theoretical Foundation

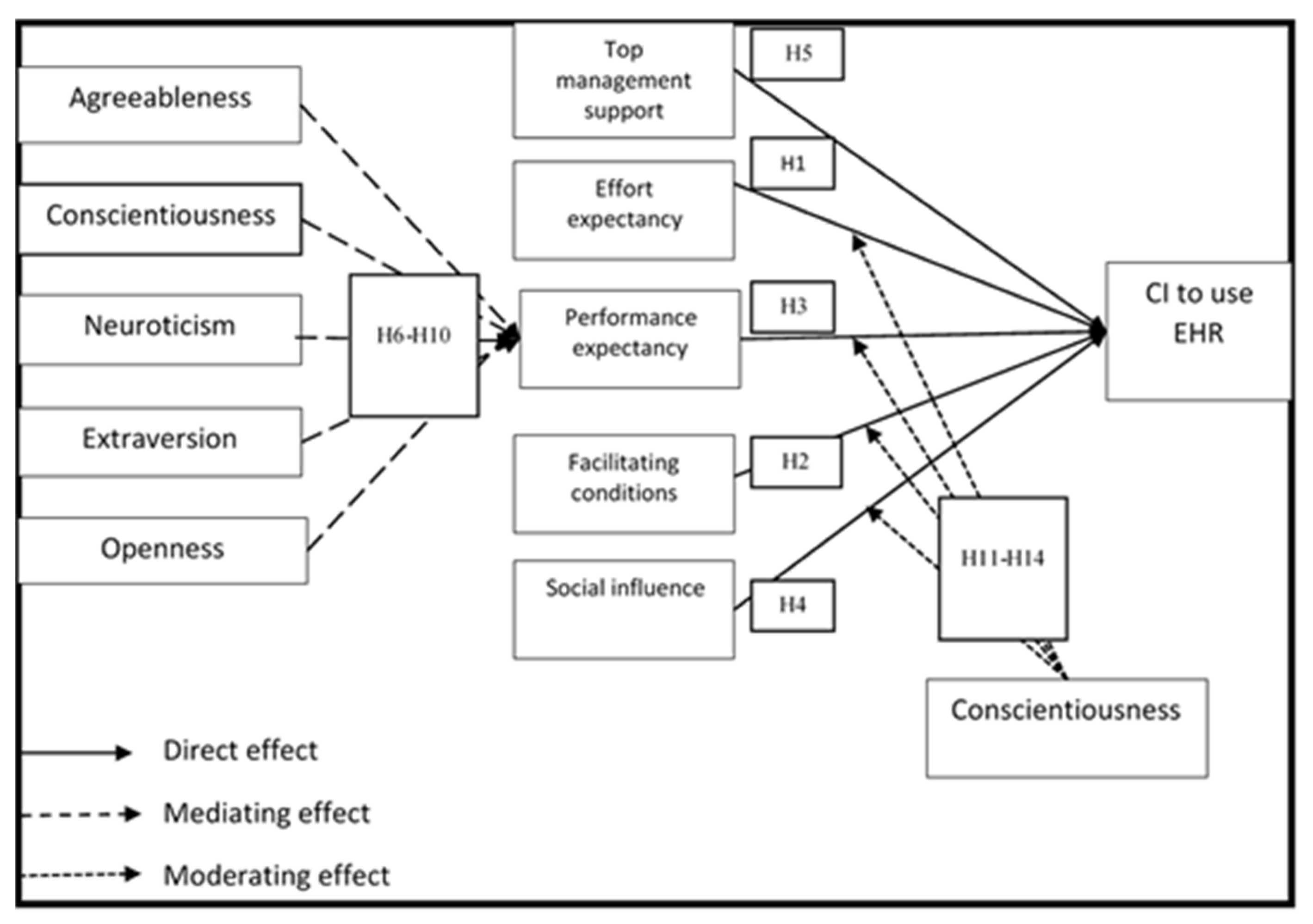

2.2. Proposed Model and Hypotheses Formulation

2.2.1. The Relationship between Effort Expectancy and Continuance Intention

2.2.2. The Relationship between Facilitating Conditions and Continuance Intention

2.2.3. The Relationship between Performance Expectancy and Continuance Intention

2.2.4. The Relationship between Social Influence and Continuance Intention

2.2.5. The Relationship between Top Management Support and Continuance Intention

2.2.6. The Relationship between Agreeableness and Continuance Intention Using Performance Expectancy as a Mediator

2.2.7. The Relationship between Openness to Experience and Continuance Intention Using Performance Expectancy as a Mediator

2.2.8. The Relationship between Neuroticism and Continuance Intention Using Performance Expectancy as a Mediator

2.2.9. The Relationship between Extraversion and Continuance Intention Using Performance Expectancy as a Mediator

2.2.10. The Relationship between Conscientiousness and Continuance Intention Using Performance Expectancy as a Mediator

2.2.11. The Relationship between UTAUT Variables and Continuance Intention Using Conscientiousness as a Moderator

2.2.12. The Relationship between Continuance Intention and Effort Expectancy Using Conscientiousness as a Moderator

2.2.13. The Relationship between Facilitating Conditions and Continuance Intention Using Conscientiousness as a Moderator

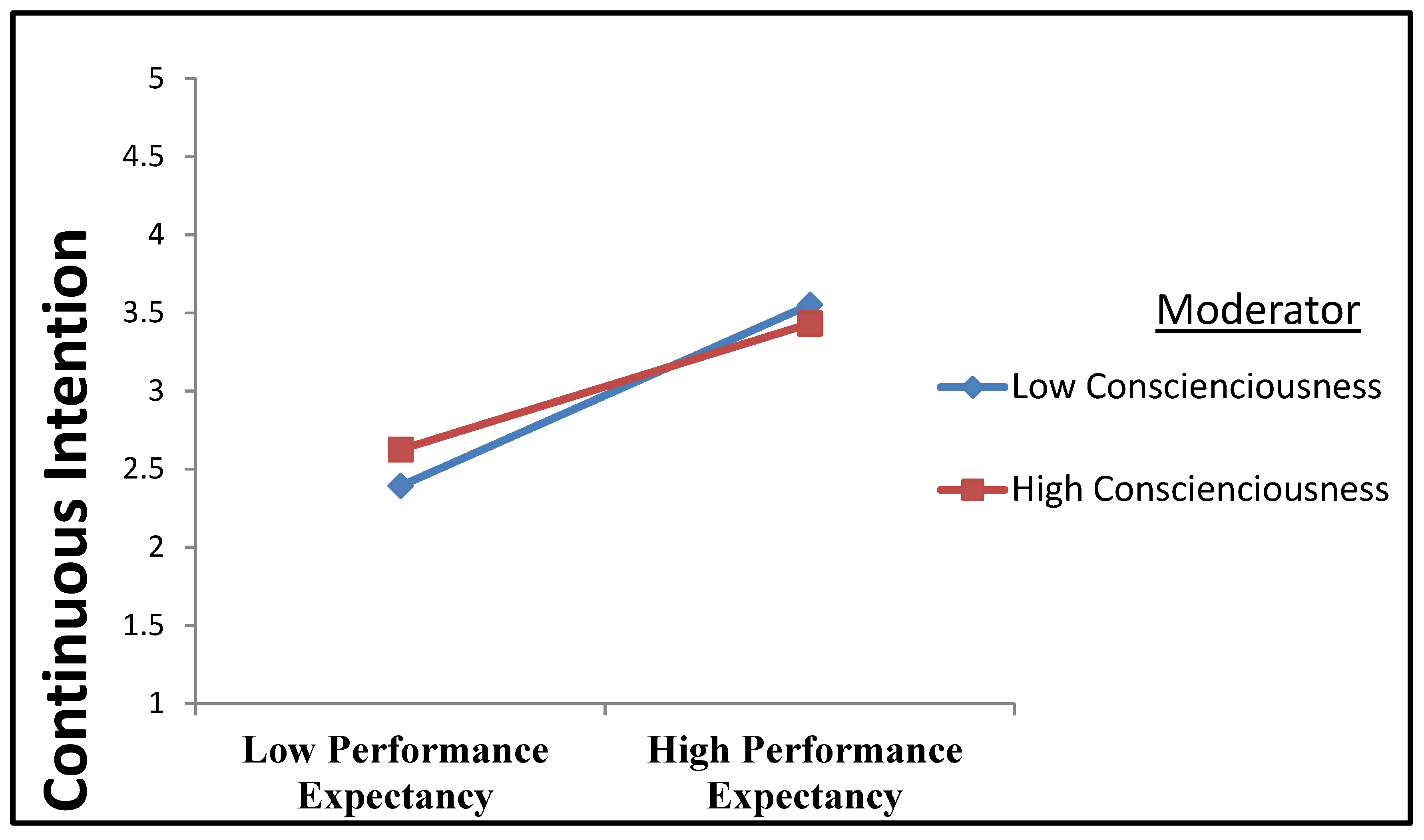

2.2.14. The Relationship between Performance Expectancy and Continuance Intention Using Conscientiousness as a Moderator

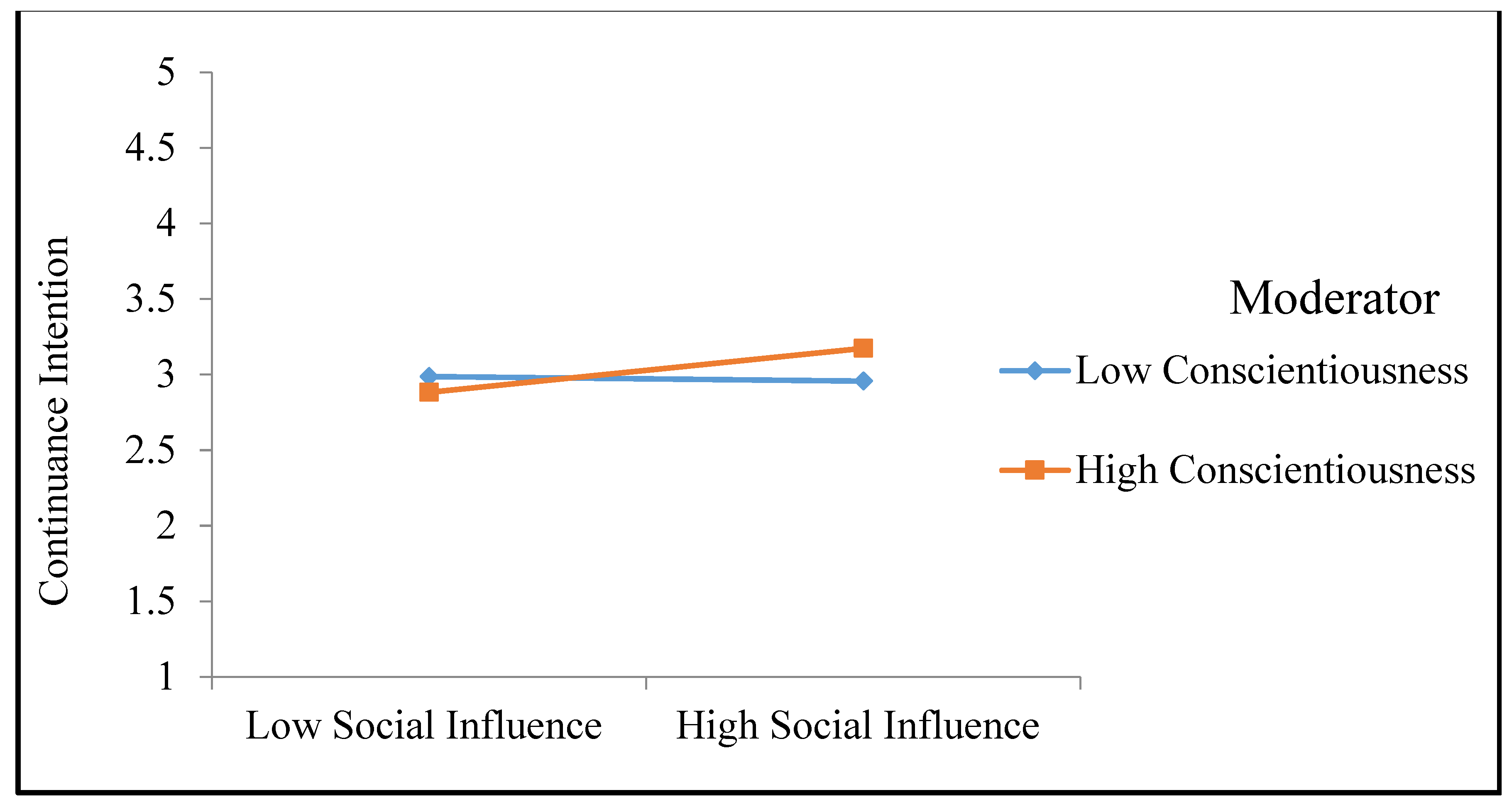

2.2.15. The Relationship between Social Influence and Continuance Intention Using Conscientiousness as a Moderator

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Context

3.2. Target Population

3.3. Sampling Procedure

3.4. Constructs and Their Measurements

4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

6.1. Theoretical Implications

6.2. Practical Implications

6.3. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Marwaha, J.S.; Landman, A.B.; Brat, G.A.; Dunn, T.; Gordon, W.J. Deploying digital health tools within large, complex health systems: Key considerations for adoption and implementation. npj Digit. Med. 2022, 5, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaber, M.M.; Alameri, T.; Ali, M.H.; Alsyouf, A.; Al-Bsheish, M.; Aldhmadi, B.K.; Jarrar, M.T. Remotely monitoring COVID-19 patient health condition using metaheuristics convolute networks from IoT-Based wearable device health data. Sensors 2022, 22, 1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gordon, W.J.; Landman, A.; Zhang, H.; Bates, D.W. Beyond validation: Getting health apps into clinical practice. NPJ Digit. Med. 2020, 3, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mather, C.; Almond, H. Using Compass (Context Optimisation Model for Person-Centred Analysis and Systematic Solutions) Theory to Augment Implementation of Digital Health Solutions. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 7111. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lustgarten, S.D.; Sinnard, M.T.; Elchert, D.M. Data after death: Record keeping considerations for unexpected departures of mental health providers. Prof. Psychol. Res. Pract. 2020, 51, 362–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, K.M.; Chen, Y.C.; Talley, P.C.; Huang, C.H. Continuance compliance of privacy policy of electronic medical records: The roles of both motivation and habit. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2018, 18, 135. [Google Scholar]

- Ayanso, A.; Herath, T.C.; O’Brien, N. Understanding continuance intentions of physicians with electronic medical records (EMR): An expectancy-confirmation perspective. Decis. Support Syst. 2015, 77, 112–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinfeld, B.I.; Keyes, J.A. Electronic medical records in a multidisciplinary health care setting: A clinical perspective. Prof. Psychol. Res. Pract. 2011, 42, 426–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kernebeck, S.; Busse, T.S.; Jux, C.; Dreier, L.A.; Meyer, D.; Zenz, D.; Zernikow, B.; Ehlers, J.P. Evaluation of an Electronic Medical Record Module for Nursing Documentation in Paediatric Palliative Care: Involvement of Nurses with a Think-Aloud Approach. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3637. [Google Scholar]

- Busse, T.S.; Kernebeck, S.; Dreier, L.A.; Meyer, D.; Zenz, D.; Haas, P.; Zernikow, B.; Ehlers, J.P. Planning for Implementation Success of an Electronic Cross-Facility Health Record for Pediatric Palliative Care Using the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 453. [Google Scholar]

- Chong, J.; Jason, T.; Jones, M.; Larsen, D. A model to measure self-assessed proficiency in electronic medical records: Validation using maturity survey data from Canadian community-based physicians. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2020, 141, 104218. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gilani, M.S.; Iranmanesh, M.; Nikbin, D.; Zailani, S. EMR continuance usage intention of healthcare professionals. Inform. Health Soc. Care 2016, 42, 153–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almaiah, M.; Hajjej, F.; Lutfi, A.; Al-Khasawneh, A.; Alkhdour, T.; Almomani, O.; Shehab, R.A. A conceptual framework for determining quality requirements for mobile learning applications using Delphi Method. Electronics 2022, 11, 788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutfi, A.; Alsyouf, A.; Almaiah, M.A.; Alrawad, M.; Abdo, A.A.K.; Al-Khasawneh, A.L.; Ibrahim, N.; Saad, M. Factors influencing the adoption of big data analytics in the digital transformation era: Case study of Jordanian SMEs. Sustainability 2022, 14, 180. [Google Scholar]

- Lutfi, A. Understanding cloud based enterprise resource planning Adoption among SMEs in Jordan. J. Theor. Appl. Inf. Technol. 2021, 99, 5944–5953. [Google Scholar]

- Tiron-Tudor, A.; Deliu, D. Big data’s disruptive effect on job profiles: Management accountants’ case study. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2021, 14, 376. [Google Scholar]

- Faida, E.W.; Supriyanto, S.; Haksama, S.; Markam, H.; Ali, A. The Acceptance and Use of Electronic Medical Records in Developing Countries within the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology Framework. Open Access Maced. J. Med. Sci. 2022, 10, 326–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maillet, É.; Mathieu, L.; Sicotte, C. Modeling factors explaining the acceptance, actual use and satisfaction of nurses using an Electronic Patient Record in acute care settings: An extension of the UTAUT. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2015, 84, 36–47. [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacherjee, A.; Lin, C.P. A unified model of IT continuance: Three complementary perspectives and crossover effects. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2015, 24, 364–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsyouf, A.; Lutfi, A.; Al-Bsheish, M.; Jarrar, M.; Al-Mugheed, K.; Almaiah, M.A.; Alhazmi, F.N.; Masa’deh, R.; Anshasi, R.J.; Ashour, A. Exposure Detection Applications Acceptance: The Case of COVID-19. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 1, 1782. [Google Scholar]

- AlQudah, A.A.; Shaalan, K. Extending UTAUT to Understand the Acceptance of Queue Management Technology by Physicians in UAE. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Emerging Technologies and Intelligent Systems, Al Buraimi, Oman, 25–26 June 2021; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Syouf, M.R.A.A.M. Personality, Top Management Support, Continuance Intention to Use Electronic Health Record System among Nurses in Jordan; Universiti Utara Malaysia: Bukit Kayu Hitam, Malaysia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Engin, M.; Gürses, F. Adoption of hospital information systems in public hospitals in Turkey: An analysis with the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology model. Int. J. Innov. Technol. Manag. 2019, 16, 1950043. [Google Scholar]

- Alsyouf, A.; Ishak, A.K. Understanding EHRs continuance intention to use from the perspectives of UTAUT: Practice environment moderating effect and top management support as predictor variable. Int. J. Electron. Healthc. 2018, 10, 24–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kari, T.; Markus, S.; Frank, L. Role of situational context in use continuance after critical exergaming incidents. Inf. Syst. J. 2020, 30, 596–633. [Google Scholar]

- Lutfi, A.A.; Idris, K.M.; Mohamad, R. AIS usage factors and impact among Jordanian SMEs: The moderating effect of environmental uncertainty. J. Adv. Res. Bus. Manag. Stud. 2017, 6, 24–38. [Google Scholar]

- Alshirah, M.; Lutfi, A.; Alshirah, A.; Ibrahim, S.M.N.; Mohammed, F. Influences of the environmental factors on the intention to adopt cloud based accounting information system among SMEs in Jordan. Accounting 2021, 7, 645–654. [Google Scholar]

- Lanzolla, G.; Suarez, F.F. Closing the technology adoption–use divide the role of contiguous user bandwagon. J. Manag. 2012, 38, 836–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutfi, A.A.; Idris, K.M.; Mohamad, R. The influence of technological, organizational and environmental factors on accounting information system usage among Jordanian small and medium-sized enterprises. Int. J. Econ. Financ. Issues 2016, 6, 240–248. [Google Scholar]

- van der Meijden, M.; Tange, H.T.J.; Hasman, A. Determinants of success of inpatient clinical information systems: A literature review. J. Am. Inform. Assoc. 2003, 10, 235–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holden, R.; Karsh, B.-T. The technology acceptance model: Its past and its future in health care. J. Biomed. Inform. 2010, 43, 159–172. [Google Scholar]

- Pynoo, B.; Devolder, P.V.T.; Sijnave, B.; Gemmel, P.; Duyck, W.; van Braak, J.; Duyck, P. Assesing hospital physicians’ acceptance of clinical information systems: A review of the relevant literature. Psychol. Belg. 2013, 53, 15–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Belief, Attitude, Intention, and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and Research; Addison-Wesley: Reading, MA, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Q.; Liu, L. The technology acceptance model: A meta-analysis of empirical findings. J. Organ. End User Comput. 2004, 16, 59–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, W.R.; He, J. A meta-analysis of the technology acceptance model. Inf. Manag. 2006, 43, 740–755. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.Y.; Wang, S.H. User acceptance of mobile internet based on the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology: Investigating the determinants and gender differences. Soc. Behav. Personal. Int. J. 2010, 38, 415–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Morris, M.G.; Davis, G.B.; Davis, F.D. User acceptance of information technology: Toward a unified view. MIS Q. 2003, 27, 425–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, P.; Anol, B. Learning online social support: An investigation of network information technology based on UTAUT. Cyber Psychol. Behav. 2008, 11, 268–272. [Google Scholar]

- Almaiah, M.A.; Al-Otaibi, S.; Lutfi, A.; Almomani, O.; Awajan, A.; Alsaaidah, A.; Alrawad, M.; Awad, A.B. Employing the TAM Model to Investigate the Readiness of M-Learning System Usage Using SEM Technique. Electronics 2022, 11, 1259. [Google Scholar]

- Almaiah, M.A.; Ayouni, S.; Hajjej, F.; Lutfi, A.; Almomani, O.; Awad, A.B. Smart Mobile Learning Success Model for Higher Educational Institutions in the Context of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Electronics 2022, 11, 1278. [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacherjee, A. Understanding information systems continuance: An expectation-confirmation model. Manag. Inf. Syst. Q. 2001, 25, 351–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacherjee, A.; Premkumar, G. Understanding changes in belief and attitude toward information technology usage: A theoretical model and longitudinal test. MIS Q. 2004, 28, 229–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Lin, I.C.; Roan, J. Barriers to physicians’ adoption of healthcare information technology: An empirical study on multiple hospitals. J. Med. Syst. 2012, 36, 1965–1977. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, M.C. Explaining and predicting users’ continuance intention toward e-learning: An extension of the expectation–confirmation mode. Comput. Educ. 2010, 54, 505–516. [Google Scholar]

- Alalwana, A.; Dwivedib, Y.; Ranab, N.; Algharabat, R. Examining factors influencing Jordanian customers’ intentions and adoption of internet banking: Extending UTAUT2 with risk. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2018, 40, 125–138. [Google Scholar]

- Alalwan, A.A.; Dwivedi, Y.K.; Rana, N.P. Factors influencing adoption of mobile banking by Jordanian bank customers: Extending UTAUT2 with trust. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2017, 37, 99–110. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, F.D.; Bagozzi, R.P.; Warshaw, P.R. User acceptance of computer technology: A comparison of two theoretical models. Manag. Sci. 1989, 35, 982–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, P.; Tamilmani, K.; Rana, N.P.; Raghavan, V. Understanding consumer adoption of mobile payment in India: Extending Meta-UTAUT model with personal innovativeness, anxiety, trust, and grievance redressal. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2020, 54, 102144. [Google Scholar]

- Niehaves, B.; Plattfaut, R. Internet adoption by the elderly: Employing IS technology acceptance theories for understanding the age-related digital divide. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2014, 23, 708–726. [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz, A.; Schwarz, C.; Jung, Y.; Pérez, B.; Wiley-Patton, S. Towards an understanding of assimilation in virtual worlds: The 3C approach. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2012, 21, 303–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Murphy, L. Remote electronic voting systems: An exploration of voters’ perceptions and intention to use. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2007, 16, 106–120. [Google Scholar]

- Lyytinen, K.; Damsgaard, J. Inter-organizational information systems adoption–a configuration analysis approach. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2011, 20, 496–509. [Google Scholar]

- van Offenbeek, M.; Boonstra, A.; Seo, D. Towards integrating acceptance and resistance research: Evidence from a telecare case study. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2013, 22, 434–454. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, S.A.; Venkatesh, V. A model of adoption of technology in the household: A baseline model test and extension incorporating household life cycle. Manag. Inf. Syst. Q. 2005, 29, 399–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfenden, A. Factors Predicting Oncology Care Providers’ Behavioral Intention to Adopt Clinical Decision Support Systems. Doctoral Dissertation, The University of Phoenix, Phoenix, AZ, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Benbasat, I.; Barki, H. Quo vadis TAM? J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2007, 8, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.Z.; Hoque, M.R.; Hu, W.; Barua, Z. Factors influencing the adoption of mHealth services in a developing country: A patient-centric study. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2020, 50, 128–143. [Google Scholar]

- Almaiah, M.; Hajjej, F.; Lutfi, A.; Al-Khasawneh, A.; Shehab, R.A.; Al-Otaibi, S.; Alrawad, M. Explaining the factors affecting students’ attitudes to using online learning (Madrasati Platform) during COVID-19. Electronics 2022, 11, 973. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, T. Understanding mobile Internet continuance usage from the perspectives of UTAUT and flow. Inf. Dev. 2011, 27, 207–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Thong, J.Y.; Chan, F.K.; Hu, P.J.H.; Brown, S.A. Extending the two-stage information systems continuance model: Incorporating UTAUT predictors and the role of context. Inf. Syst. J. 2011, 21, 527–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, T.; Pearson, A.W.; Pearson, R.; Kellermanns, F.W. Five-factor model personality traits as predictors of perceived and actual usage of technology. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2015, 24, 374–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrawashdeh, T. The Extended UTAUT Acceptance Model of Computer-Based Distance Training System among Public Sector’s Employees in Jordan. Doctoral Dissertation, Universiti Utara Malaysia, Bukit Kayu Hitam, Malaysia, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Dadayan, L.; Ferro, E. When technology meets the mind: A comparative study of the Technology Acceptance Model. In Electronic Government. EGOV 2005; Wimmer, M.T.R.G.Å.A.K., Ed.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2005; Volume 3591, pp. 137–144. [Google Scholar]

- Nanayakkara, C. A model of user acceptance of learning management systems: A study within tertiary institutions in New Zealand. Int. J. Learn. 2007, 13, 223–232. [Google Scholar]

- Theotokis, A.; Pramatari, K.; Doukidis, G. Consumer Acceptance of Technology Contact. 2009. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=1389502 (accessed on 3 January 2020).

- Theotokis, A.; Vlachos, P.; Pramatari, K. The moderating role of customer–technology contact on attitude towards technology-based services. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2008, 17, 343–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neufeld, D.; Dong, L.; Higgins, C. Charismatic leadership and user acceptance of information technology. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2007, 16, 494–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, W.; Kelly, J.R.R. The Influence of individual differences on skill in end-user computing. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 1992, 9, 93–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, D.; Kletke, M. Individual adjustment during technological innovation: A research framework. Behav. Inf. Technol. 1990, 9, 257–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zmund, R. Perceptions of Cognitive Styles: Acquisition, Exhibition and Implications for Information System Design. J. Manag. 1979, 5, 7–20. [Google Scholar]

- Thatcher, J.; Perrewé, P. An empirical examination of individual traits as antecedents to computer anxiety and computer self-efficacy. Manag. Inf. Syst. Q. 2002, 26, 381–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Thong, J.Y.; Xu, X. Consumer acceptance and use of information technology: Extending the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology. Manag. Inf. Syst. Q. 2012, 36, 157–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutfi, A.; Saad, M.; Almaiah, M.A.; Alsaad, A.; Al-Khasawneh, A.; Alrawad, M.; Alsyouf, A.; Al-Khasawneh, A.L. Actual Use of Mobile Learning Technologies during Social Distancing Circumstances: Case Study of King Faisal Univer-sity Students. Sustainability 2022, 1, 1245. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, C.; Palvia, P.; Chen, J.-L. Information technology adoption behavior life cycle: Toward a Technology Continuance Theory (TCT). Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2009, 29, 309–320. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Hadban, W.K.M.; Hashim, K.F.; Yusof, S.A.M. Investigating the organizational and the environmental issues that influence the adoption of healthcare information systems in public hospitals of Iraq. Comput. Inf. Sci. 2016, 9, 126–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, H.-Y.; Liu, F.-H.; Tsou, H.-T.; Chen, L.-J. Openness of technology adoption, top management support and service innovation: A social innovation perspective. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2018, 34, 575–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gangwar, H.; Date, H.; Ramaswamy, R. Understanding determinants of cloud computing adoption using an integrated TAM-TOE model. J. Enterp. Inf. Manag. 2015, 28, 107–130. [Google Scholar]

- Cresswell, K.; Sheikhb, A. Organizational issues in the implementation and adoption of health information technology innovations: An interpretative review. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2013, 82, 73–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hameed, M.A.; Counsell, S.; Swift, S. A conceptual model for the process of IT innovation adoption in organizations. J. Eng. Technol. Manag. 2012, 29, 358–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeyaraj, A. Models of Information Technology Use: Meta-Review and Research Directions. J. Comput. Inf. Syst. 2022, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boontarig, W.; Chutimasakul, W.; Papasratorn, B. A conceptual model of intention to use health information associated with online social network. In Proceedings of the Computing, Communications and IT Applications Conference (ComComAp), Hong Kong, China, 1–4 April 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, T.; Lu, Y. The effects of personality traits on user acceptance of mobile commerce. Int. J. Hum.–Comput. Interact. 2011, 27, 545–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devaraj, S.; Easley, R.F.; Crant, J.M. Research note-how does personality matter? Relating the five-factor model to technology acceptance and use. Inf. Syst. Res. 2008, 19, 93–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harle, C.; Gruber, L.; Dewar, M. Factors in medical student beliefs about electronic health record use. Perspect. Health Inf. Manag. 2014, 1, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Terry, L.; Thorpe, C.F.; Giles, G.; Brown, J.B.; Harris, S.B.; Reid, G.J.; Thind, A.; Stewart, M. Implementing electronic health records Key factors in primary care. Can. Fam. Physician 2008, 54, 730–736. [Google Scholar]

- Thakur, R.; Hsu, S.H.; Fontenot, G. Innovation in healthcare: Issues and future trend. J. Bus. Res. 2012, 65, 562–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, E.; Heslinga, D. Bridging the IT adoption gap for small physician practices: An action research study on electronic health records. Inf. Syst. Manag. 2006, 24, 5–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludwick, D.A.; Doucette, J. Adopting electronic medical records in primary care: Lessons learned from health information systems implementation experience in seven countries. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2009, 78, 22–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhalgh, T.; Stramer, K.; Bratan, T.; Byrne, E.; Mohammad, Y.; Russell, J. Introduction of shared electronic records: Multi-site case study using diffusion of innovation theory. Br. Med. J. 2008, 337, a1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGinn, C.A.; Grenier, S.; Duplantie, J.; Shaw, N.; Sicotte, C.; Mathieu, L.; Leduc, Y.; Légaré, F.; Gagnon, M.P. Comparison of user groups’ perspectives of barriers and facilitators to implementing electronic health records: A systematic review. BMC Med. 2011, 9, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boonstra, A.; Broekhuis, M. Barriers to the acceptance of electronic medical records by physicians from systematic review to taxonomy and interventions. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2010, 10, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venkatesh, V.; Brown, S.A. A longitudinal investigation of personal computers in homes: Adoption determinants and emerging challenges. Manag. Inf. Syst. Q. 2001, 25, 71–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsyouf, A.; Masa’deh, R.E.; Albugami, M.; Lutfi, A.-B.M.A.; Alsubahi, N. Risk of fear and anxiety in utilising health app surveillance due to COVID-19: Gender differences analysis. Risks 2021, 9, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidgen, R.; Henneberg, S.; Naudé, P. What sort of community is the European Conference on Information Systems? A social network analysis 1993–2005. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2007, 16, 5–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshirah, M.; Alshirah, A.; Lutfi, A. Audit committee’s attributes, overlapping memberships on the audit committee and corporate risk disclosure: Evidence from Jordan. Accounting 2021, 7, 423–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Davis, F.D. A theoretical extension of the technology acceptance model: Four longitudinal field studies. Manag. Sci. 2000, 46, 186–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragu-Nathan, S.; Apigian, C.H.; Ragu-Nathan, T.S.; Tu, Q. A path analytic study of the effect of top management support for information systems performance. Omega 2004, 32, 459–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruque-Cámara, S.; Vargas-Sánchez, A.; Hernández-Ortiz, M.J. Organizational determinants of IT adoption in the pharmaceutical distribution sector. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2004, 13, 133–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yigitbasioglu, M. The role of institutional pressures and top management support in the intention to adopt cloud computing solutions. J. Enterp. Inf. Manag. 2015, 28, 579–594. [Google Scholar]

- Low, C.; Chen, Y.; Wu, M. Understanding the determinants of cloud computing adoption. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2011, 111, 1006–1023. [Google Scholar]

- Purvis, R.L.; Sambamurthy, V.; Zmud, R.W. The assimilation of knowledge platforms in organizations: An empirical investigation. Organ. Sci. 2001, 12, 117–135. [Google Scholar]

- Jarvenpaa, S.L.; Ives, B. Executive involvement and participation in the management of information technology. Manag. Inf. Syst. Q. 1991, 15, 205–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonard-Barton, D.; Deschamps, I. Managerial influence in the implementation of new technology. Manag. Sci. 1988, 34, 1252–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, T.H.; Zmud, R.W. Unifying the fragmented models of information systems implementation. In Critical Issues in Information Systems Research; Boland, R., Hirschheim, R., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1987; pp. 227–251. [Google Scholar]

- Deliu, D. Empathetic leadership–Key element for inspiring strategic management and a visionary effective corporate governance. J. Emerg. Trends Mark. Manag. 2019, 1, 280–292. [Google Scholar]

- Lutfi, A.; Al-Khasawneh, A.L.; Almaiah, M.A.; Alsyouf, A.; Alrawad, M. Business Sustainability of Small and Medium Enterprises during the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Role of AIS Implementation. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshirah, M.H.; Alshira’h, A.F.; Lutfi, A. Political connection, family ownership and corporate risk disclosure: Empirical evidence from Jordan. Meditari Account. Res. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boswell, R.A. Implementing electronic health records: Implications for HR professionals. Strateg. HR Rev. 2013, 12, 262–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R.; Yetton, P. The contingent effects of management support and task interdependence on successful information systems implementation. Manag. Inf. Syst. Q. 2003, 27, 533–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Khasawneh, A.; Barakat, H. The role of the Hashemite leadership in the development of human resources in Jordan: An analytical study. Int. Rev. Manag. Mark. 2016, 6, 654–667. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, P.T., Jr.; McCrae, R.R. The revised neo personality inventory (NEO-PI-R). In The SAGE Handbook of Personality Theory and Assessment; Saklofske, D., Ed.; Personality Measurement and Testing, 2; SAGE Publishing: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2008; pp. 79–198. [Google Scholar]

- Graziano, W.G.; Eisenberg, N. Agreeableness: A dimension of personality. In Handbook of Personality Psychology; Hogan, R., Johnson, J., Briggs, S., Eds.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 1997; pp. 795–824. [Google Scholar]

- Barrick, M.R.; Mount, M.K.; Judge, T.A. Personality and performance at the beginning of the new millennium: What do we know and where do we go next? Int. J. Sel. Assess. 2001, 9, 9–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrawad, M.; Lutfi, A.; Alyatama, S.; Elshaer, I.; Almaiah, M. Perception of occupational and environmental risks and hazards among mineworkers: A psychometric paradigm approach. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bazerman, M.H.; Neale, M.A. Negotiating Rationally; Simon and Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Ross, C.; Orr, E.S.; Sisic, M.; Arseneault, J.M.; Simmering, M.G.; Orr, R.R. Personality and motivations associated with Facebook use. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2009, 25, 578–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, D.; Clark, L.A. Extraversion and its positive emotional core. In Handbook of Personality Psychology; Hogan, R., Johnson, J.B.S., Eds.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 1997; pp. 767–793. [Google Scholar]

- Barrick, M.R.; Mount, M.K. The big five personality dimensions and job performance: A meta-analysis. Pers. Psychol. 1991, 44, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, M. Diffusion of Innovations; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Khasawneh, L.; Malkawi, N.M.; AlGarni, A.A. Sources of recruitment at foreign commercial banks in Jordan and their impact on the job performance proficiency. Banks Bank Syst. 2018, 13, 12–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Costa, T., Jr.; McCrae, R.R.; Dye, D.A. Facet scales for agreeableness and conscientiousness: A revision of the NEO Personality Inventory. Personal. Individ. Differ. 1991, 12, 887–898. [Google Scholar]

- Chiorri, C.; Garbarino, S.; Bracco, F.; Magnavita, N. Personality traits moderate the effect of workload sources on perceived workload in flying column police officers. Front. Psychol. 2015, 6, 1835. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.I.; Yang, H.L. The role of personality traits in UTAUT model under online stocking. Contemp. Manag. Res. 2005, 1, 69–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Citurs, A. Incorporating personality into UTAUT: Individual differences and user acceptance of IT. In Proceedings of the Annual Americas’ Conference on Information Systems (AMCIS), New York, NY, USA, 6–8 August 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, P., Jr.; McCrae, R. Revised NEO Personality Inventory (NEO-PI-R) and NEO Five-Factor Inventory (NEO-FFI): Professional Manual; Psychological Assessment Resources: Odessa, FL, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Barrick, M.R.; Mount, M.K. Select on conscientiousness and emotional stability. In The Blackwell Handbook of Principles of Organizational Behavior; Locke, E.A., Ed.; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2000; pp. 15–28. [Google Scholar]

- Tamilmani, K.; Rana, N.P.; Wamba, S.F.; Dwivedi, R. The extended Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT2): A systematic literature review and theory evaluation. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2020, 57, 102269. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, M.D.; Rana, N.P.; Dwivedi, Y.K. The unified theory of acceptance and use of technology (UTAUT): A literature review. J. Enterp. Inf. Manag. 2015, 28, 443–488. [Google Scholar]

- Alsyouf, A. Mobile Health for COVID-19 Pandemic Surveillance in Developing Countries: The case of Saudi Arabia. Solid State Technol. 2020, 63, 2474–2485. [Google Scholar]

- Alsadan, M.; El Metwally, A.; Ali, A.; Jamal, A.; Khalifa, M.; Househ, M. Health Information Technology (HIT) in Arab countries: A systematic review study on HIT progress. J. Health Inform. Dev. Ctries. 2015, 9, 32–49. [Google Scholar]

- Alsyouf, A.; Ishak, A.K. Acceptance of electronic health record system among nurses: The effect of technology readiness. Asian J. Inf. Technol. 2017, 16, 414–421. [Google Scholar]

- Ajlouni, M.T.; Dawani, H.; Diab, S.M. Home Health Care (HHC) managers perceptions about challenges and obstacles that hinder HHC services in Jordan. Glob. J. Health Sci. 2015, 7, 121–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajlouni, M. Human Resources for Health Country Profile-Jordan; EMRO, World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Dua’A, N.; Othman, M.; Yahya, H. Implementation of an EHR System (Hakeem) in Jordan: Challenges and recommendations for governance. HIM-Interchange J. 2013, 3, 10–12. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Nassar, B.; Abdullah, M.S.; Osman, W.R.S. Overcoming challenges to use electronic medical records system (EMRs) in Jordan Hospitals. Int. J. Comput. Sci. Netw. Secur. 2011, 11, 51–58. [Google Scholar]

- Meinert, D.B.; Peterson, D. Perceived importance of EMR functions and physician characteristics. J. Syst. Inf. Technol. 2009, 11, 57–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holtz, B.; Krein, S. Understanding nurse perceptions of a newly implemented electronic medical record system. J. Technol. Hum. Serv. 2011, 29, 247–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krejcie, R.V.; Morgan, D.W. Table for determining sample size from a given population. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1970, 30, 607–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Anderson, B.B.J.R.E.; Tatham, R.L. Multivariate Data Analysis, 6th ed.; Pearson Education: Cranbury, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health. Ministry of Health Annual Statistical Book 2015. 2015. Available online: http://www.moh.gov.jo/AR/Pages/Periodic-Newsletters.aspx (accessed on 1 April 2016).

- Basri, W. Factors Affecting Information Communication Technology Acceptance and Usage of Public Organizations in Saudi Arabia. Doctoral Dissertation, International Islamic University, Islamabad, Pakistan, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Igbaria, M. End-user computing effectiveness: A structural equation model. Omega 1990, 18, 637–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, J.M.; Zhou, J. When openness to experience and conscientiousness are related to creative behavior: An interactional approach. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 86, 513–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tepper, J.; Duffy, M.K.; Shaw, J.D. Personality moderators of the relationship between abusive supervision and subordinates’ resistance. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 86, 974–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brislin, W. Research instruments. Field methods in cross-cultural research. Cross-Cult. Res. Methodol. Ser. 1986, 8, 137–164. [Google Scholar]

- Gefen, D.; Rigdon, E.; Straub, D. An update and extension to SEM guidelines for administrative and social science research. MIS Q. 2011, 35, A1–A7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M.; Straub, D. A critical look at the use of PLS-SEM in MIS Quarterly. Manag. Inf. Syst. Q. 2012, 36, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutfi, A.; Al-Okaily, M.; Alsyouf, A.; Alsaad, A.; Taamneh, A. The impact of AIS usage on AIS effectiveness among Jordanian SMEs: A multi-group analysis of the role of firm size. Glob. Bus. Rev. 2020, 21, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, Y. On the evaluation of structural equation models. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1988, 16, 74–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM); SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, F.J., Jr.; Sarstedt, M.; Hopkins, L.; Kuppelwieser, V.G. Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM): An emerging tool in business research. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2014, 26, 106–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, B. Using PLS to investigate interaction effects between higher order branding constructs. In Handbook of Partial Least Squares; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; pp. 621–652. [Google Scholar]

- Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.; Hair, J. PLS-SEM: Looking back and moving forward. Long Range Plan. 2014, 47, 132–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM: Indeed a silver bullet. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2011, 19, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav. Res. Methods 2008, 40, 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aiken, L.; West, S. Detecting interactions in multiple regression: Measurement error, power, and design considerations. Score 1993, 16, 14–15. [Google Scholar]

- Marcus, B.; Schuler, H.; Quell, P.; HuÈmpfner, G.G. Measuring counterproductivity: Development and initial validation of a German self-report questionnaire. Int. J. Sel. Assess. 2002, 10, 18–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Sykes, T.A.; Zhang, X. ‘Just what the doctor ordered’: A revised UTAUT for EMR system adoption and use by doctors. In Proceedings of the 44th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Kauai, HI, USA, 4–7 January 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Venkatesh, V.; Morris, M.G. Why don’t men ever stop to ask for directions? Gender, social influence, and their role in technology acceptance and usage behavior. Manag. Inf. Syst. Q. 2000, 24, 115–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nofal, M.I.M.; Yusof, Z.M. Conceptual model of enterprise resource planning and business intelligence systems usage. Int. J. Bus. Inf. Syst. 2016, 21, 178–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, H.; Lee, S.; Kim, C. What drives the adoption of building information modeling in design organizations? An empirical investigation of the antecedents affecting architects’ behavioral intention. Autom. Constr. 2015, 49, 92–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Sun, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y. Understanding SaaS adoption from the perspective of organizational users: A tripod readiness model. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 45, 254–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.F.; Hsiao, J.L. An investigation on physicians’ acceptance of hospital information systems: A case study. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2012, 81, 810–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sargent, K.; Hyland, P.; Sawang, S. Factors influencing the adoption of information technology in a construction business. Australas. J. Constr. Econ. Build. 2012, 12, 72–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, E. Knowledge activation: Accessibility, applicability, and salience. In Social Psychology: Handbook of Basic Principles; Higgins, E., Kruglanski, A., Eds.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1996; pp. 133–168. [Google Scholar]

- Punnoose, A. Determinants of intention to use eLearning based on the technology acceptance model. J. Inf. Technol. Educ. Res. 2012, 11, 301–337. [Google Scholar]

- Kashdan, T.B.; Rose, P.; Fincham, F.D. Curiosity and exploration: Facilitating positive subjective experiences and personal growth opportunities. J. Personal. Assess. 2004, 82, 291–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reiss, S. Multifaceted nature of intrinsic motivation: The theory of 16 basic desires. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2004, 8, 179–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loewenstein, G. The psychology of curiosity: A review and reinterpretation. Psychol. Bull. 1994, 116, 75–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malone, T. Toward a theory of intrinsically motivating instruction. Cogn. Sci. 1981, 5, 333–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malone, T. What makes computer games fun? Byte 1981, 6, 258–277. [Google Scholar]

- Venkatesh, V.; Sykes, T.A.; Venkatraman, S. Understanding e-Government portal use in rural India: Role of demographic and personality characteristics. Inf. Syst. J. 2014, 24, 249–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steege, L.; Boiano, J.M.; Sweeney, M.H. NIOSH health and safety practices survey of healthcare workers: Training and awareness of employer safety procedures. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2014, 57, 640–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Bsheish, M.; Mustafa, M.b.; Ismail, M.; Meri, A.; Dauwed, M. Perceived management commitment and psychological empowerment: A study of intensive care unit nurses’ safety. Saf. Sci. 2019, 118, 632–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Province | Hospital | Number of Nurses in the Hospital | Total Nurses in the Hospital | Minimum No, of Nurses to Be Collected from the Hospital |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| North | 1 | RN: 132 | 149 | 23 |

| Diploma: 17 | ||||

| 2 | RN: 126 | 137 | 21 | |

| Diploma: 11 | ||||

| 3 | RN: 123 | 141 | 21 | |

| Diploma: 18 | ||||

| 4 | RN: 90 | 110 | 17 | |

| Diploma: 20 | ||||

| 5 | RN: 131 | 158 | 24 | |

| Diploma: 27 | ||||

| Central | 6 | RN: 444 | 528 | 79 |

| Diploma: 84 | ||||

| 7 | RN: 135 | 181 | 27 | |

| Diploma: 46 | ||||

| 8 | RN: 363 | 472 | 71 | |

| Diploma: 109 | ||||

| South | 9 | RN: 186 | 226 | 34 |

| Diploma: 40 | ||||

| 10 | RN: 70 | 92 | 14 | |

| Diploma: 22 | ||||

| Total | 10 hospitals | RN: 1800 | 2194 | 331 |

| Diploma: 394 |

| Items | Category | N | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 141 | 29.8 |

| Female Missing data | 332 0 | 70.2 0 | |

| Total | 473 | 100 | |

| Age | 20–30 years | 208 | 44 |

| 31–40 years | 183 | 38.7 | |

| 41–50 | 75 | 15.9 | |

| 51–60 | 3 | 0.6 | |

| Missing data | 4 | 0.8 | |

| Total | 473 | 100 | |

| Education level | Diploma Degree | 81 | 17.1 |

| Bachelor Degree | 363 | 76.7 | |

| Master Degree | 24 | 5.1 | |

| Ph.D. Degree | 2 | 0.4 | |

| Missing data | 3 | 0.6 | |

| Total | 473 | 100 | |

| Profession Experience | 1–5 | 128 | 27.1 |

| 6–10 | 123 | 26 | |

| 11–15 | 100 | 21.1 | |

| 16–20 | 74 | 15.6 | |

| 21–25 | 38 | 8 | |

| 26–30 | 6 | 1.3 | |

| 31–35 | 1 | 0.2 | |

| Missing data | 3 | 0.6 | |

| Total | 473 | 100 | |

| Current Hospital Experience | 1–5 | 220 | 46.5 |

| 6–10 | 118 | 24.9 | |

| 11–15 | 60 | 12.7 | |

| 16–20 | 46 | 9.7 | |

| 21–25 | 19 | 4 | |

| Missing data | 10 | 2.1 | |

| Total | 473 | 100 | |

| Hospital | 1 | 59 | 12.5 |

| 2 | 23 | 4.9 | |

| 3 | 86 | 18.2 | |

| 4 | 36 | 7.6 | |

| 5 | 97 | 20.5 | |

| 6 | 29 | 6.1 | |

| 7 | 40 | 8.5 | |

| 8 | 23 | 4.9 | |

| 9 | 42 | 8.9 | |

| 10 | 38 | 8 | |

| Missing data | 0 | 0 | |

| Total | 473 | 100 | |

| Department | ICU | 47 | 9.90 |

| CCU | 24 | 5.10 | |

| ER | 52 | 10.1 | |

| Dialysis | 33 | 7.00 | |

| Floor | 223 | 47.1 | |

| Operating room | 94 | 19.9 | |

| Missing data | 0 | 0.00 | |

| Total | 473 | 100 |

| Constructs | Measurement Items | Loadings | Cronbach’s Alpha | Composite Reliability (CR) | Average Variance Extracted (AVE) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agreeableness | A1 | 0.810 | 0.734 | 0.830 | 0.552 |

| A10 | 0.762 | ||||

| A4 | 0.762 | ||||

| A7 | 0.626 | ||||

| Conscientiousness | C12 | 0.856 | 0.885 | 0.831 | 0.567 |

| C7 | 0.864 | ||||

| C8 | 0.791 | ||||

| C9 | 0.406 | ||||

| Continuous Intention | CI1 | 0.863 | 0.937 | 0.950 | 0.762 |

| CI2 | 0.856 | ||||

| CI3 | 0.837 | ||||

| CI4 | 0.899 | ||||

| CI5 | 0.907 | ||||

| CI6 | 0.873 | ||||

| Extraversion | E11 | 0.775 | 0.719 | 0.827 | 0.545 |

| E4 | 0.648 | ||||

| E7 | 0.724 | ||||

| E8 | 0.798 | ||||

| Effort expectancy | EE1 | 0.856 | 0.886 | 0.917 | 0.693 |

| EE2 | 0.897 | ||||

| EE3 | 0.885 | ||||

| EE4 | 0.637 | ||||

| EE5 | 0.859 | ||||

| Facilitating Condition | FC1 | 0.823 | 0.875 | 0.909 | 0.666 |

| FC2 | 0.861 | ||||

| FC3 | 0.798 | ||||

| FC4 | 0.814 | ||||

| FC5 | 0.783 | ||||

| Neuroticism | N11 | 0.765 | 0.798 | 0.856 | 0.544 |

| N12 | 0.647 | ||||

| N2 | 0.768 | ||||

| N6 | 0.809 | ||||

| N9 | 0.687 | ||||

| Openness to Experience | O11 | 0.708 | 0.682 | 0.792 | 0.560 |

| O2 | 0.784 | ||||

| O3 | 0.753 | ||||

| Performance Expectancy | PE1 | 0.900 | 0.883 | 0.927 | 0.810 |

| PE2 | 0.919 | ||||

| PE3 | 0.880 | ||||

| Social Influence | SI1 | 0.637 | 0.886 | 0.910 | 0.562 |

| SI2 | 0.713 | ||||

| SI3 | 0.832 | ||||

| SI4 | 0.863 | ||||

| SI5 | 0.815 | ||||

| SI6 | 0.766 | ||||

| SI7 | 0.708 | ||||

| SI8 | 0.627 | ||||

| Top Management Support | TMS1 | 0.737 | 0.879 | 0.902 | 0.537 |

| TMS2 | 0.777 | ||||

| TMS3 | 0.758 | ||||

| TMS4 | 0.707 | ||||

| TMS5 | 0.742 | ||||

| TMS6 | 0.791 | ||||

| TMS7 | 0.696 | ||||

| TMS8 | 0.644 |

| Constructs | A | C | CI | E | EE | FC | N | O | PE | SI | TMS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 0.743 | ||||||||||

| C | 0.714 | 0.753 | |||||||||

| CI | 0.442 | 0.395 | 0.873 | ||||||||

| E | 0.670 | 0.695 | 0.396 | 0.739 | |||||||

| EE | 0.479 | 0.391 | 0.712 | 0.440 | 0.832 | ||||||

| FC | 0.400 | 0.302 | 0.518 | 0.315 | 0.558 | 0.816 | |||||

| N | 0.253 | 0.368 | 0.059 | 0.182 | 0.070 | 0.067 | 0.738 | ||||

| O | 0.678 | 0.650 | 0.417 | 0.679 | 0.470 | 0.357 | 0.182 | 0.749 | |||

| PE | 0.393 | 0.332 | 0.766 | 0.350 | 0.635 | 0.480 | 0.046 | 0.388 | 0.900 | ||

| SI | 0.408 | 0.325 | 0.544 | 0.328 | 0.541 | 0.520 | −0.085 | 0.389 | 0.550 | 0.750 | |

| TMS | 0.363 | 0.206 | 0.439 | 0.298 | 0.486 | 0.652 | −0.098 | 0.321 | 0.477 | 0.613 | 0.733 |

| No. | Hypothesis | Beta | p-Value | t Statistic | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | Effort Expectancy → Continuous Intention | 0.314 | 0.000 | 5.284 *** | Supported |

| H2 | Facilitating Conditions → Continuous Intention | 0.091 | 0.025 | 2.246 ** | Supported |

| H3 | Performance Expectancy → Continuous Intention | 0.491 | 0.000 | 10.425 *** | Supported |

| H4 | Social Influence → Continuous Intention | 0.075 | 0.080 | 1.756 * | Supported |

| H5 | Top Management Support → Continuous Intention | −0.067 | 0.13 | 1.515 | Not supported |

| Bootstrapped Confidence Internal | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hypothesis | Relationship | Indirect Effect (Beta) | SE | t Value | 95% LL | 95% UL | Decision |

| H6 | A → PE → CI | 0.104 | 0.035 | 2.958 *** | 0.034 | 0.171 | Supported |

| H7 | C → PE → CI | 0.018 | 0.037 | 0.487 | −0.060 | 0.083 | Not supported |

| H8 | E → PE → CI | 0.033 | 0.029 | 1.156 | −0.021 | 0.095 | Not supported |

| H9 | N → PE → CI | −0.033 | 0.034 | 0.975 | −0.093 | 0.040 | Not supported |

| H10 | O → PE → CI | 0.092 | 0.036 | 2.575 *** | 0.020 | 0.161 | Supported |

| Hypotheses | Relationship | Beta | Standard Error | t Value | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H11 | EE → CI | −0.029 | 0.054 | 0.532 | Not supported |

| H12 | FCC → CI | −0.047 | 0.037 | 1.269 | Not supported |

| H13 | PEC → CI | −0.097 | 0.048 | 2.021 * | Supported |

| H14 | SIC → CI | 0.095 | 0.045 | 2.133 * | Supported |

| No. | Hypothesis | Beta | t Statistic | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | EE → CI | 0.314 | 5.284 *** | Supported |

| H2 | FC → CI | 0.091 | 2.246 ** | Supported |

| H3 | PE → CI | 0.491 | 10.425 *** | Supported |

| H4 | SI → CI | 0.075 | 1.756 * | Supported |

| H5 | TMS → CI | −0.067 | 1.515 | Not supported |

| H6 | A → PE → CI | 0.104 | 2.958 *** | Supported |

| H7 | C → PE → CI | 0.018 | 0.487 | Not supported |

| H8 | E → PE → CI | 0.033 | 1.156 | Not supported |

| H9 | N → PE → CI | −0.033 | 0.975 | Not supported |

| H10 | O → PE → CI | 0.092 | 2.575 *** | Supported |

| H11 | EE × C → CI | −0.029 | 0.532 | Not supported |

| H12 | FC × C → CI | −0.047 | 1.269 | Not supported |

| H13 | PE × C → CI | −0.097 | 2.021 ** | Supported |

| H14 | SI × C → CI | 0.095 | 2.133 ** | Supported |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alsyouf, A.; Ishak, A.K.; Lutfi, A.; Alhazmi, F.N.; Al-Okaily, M. The Role of Personality and Top Management Support in Continuance Intention to Use Electronic Health Record Systems among Nurses. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 11125. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191711125

Alsyouf A, Ishak AK, Lutfi A, Alhazmi FN, Al-Okaily M. The Role of Personality and Top Management Support in Continuance Intention to Use Electronic Health Record Systems among Nurses. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(17):11125. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191711125

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlsyouf, Adi, Awanis Ku Ishak, Abdalwali Lutfi, Fahad Nasser Alhazmi, and Manaf Al-Okaily. 2022. "The Role of Personality and Top Management Support in Continuance Intention to Use Electronic Health Record Systems among Nurses" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 17: 11125. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191711125

APA StyleAlsyouf, A., Ishak, A. K., Lutfi, A., Alhazmi, F. N., & Al-Okaily, M. (2022). The Role of Personality and Top Management Support in Continuance Intention to Use Electronic Health Record Systems among Nurses. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(17), 11125. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191711125